CHAPTER 27

THE PRODUCTION MEETING

This chapter's title might suggest that one meeting is enough. Typically the production meeting is the culmination of many weekly planning sessions, and the last one exists to sign off on everything important before the unit launches into action. Below are the main areas a production meeting must cover. Everyone heading a department must be present with their respective breakdowns derived from a close reading of the script: producer, production manager (PM), director, script supervisor (also known as continuity supervisor), director of photography (DP), art director, and head of sound. Everyone must have visited locations and accepted them as viable.

TROUBLESHOOTING

Anyone with a problem to be resolved brings it up at this meeting. Now is the time to coordinate everyone's efforts and to make corrections or changes if something has been overlooked or needs a schedule change.

DRAFT SCHEDULE

Preliminary budgeting will be based on the shortest practical schedule. Everyone must check the logistics of travel, time to build and strike sets, and so on. Some time will be built in for contingencies such as bad weather or breakdowns.

DRAFT BUDGET

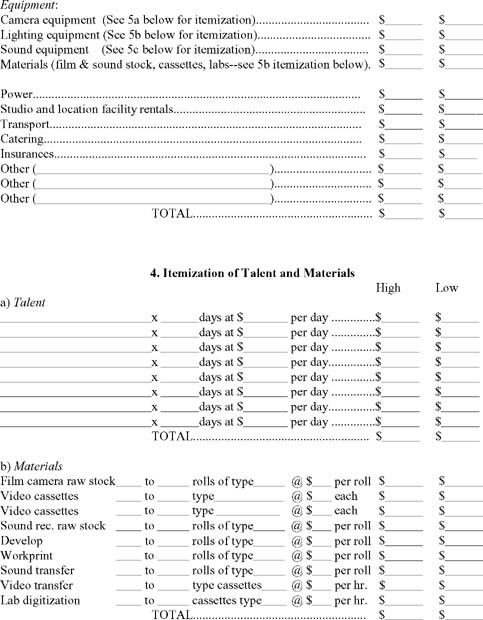

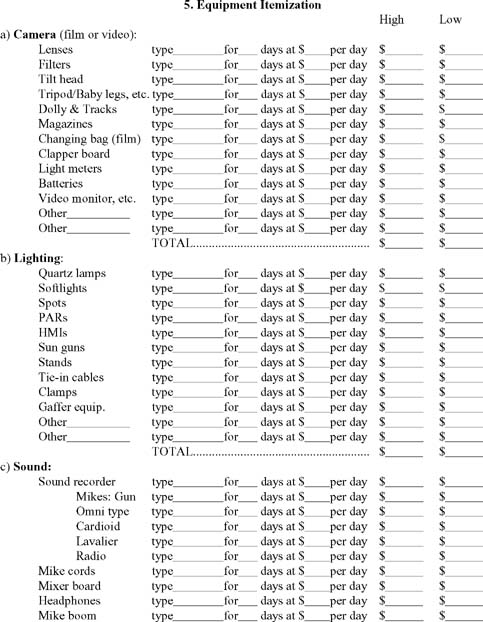

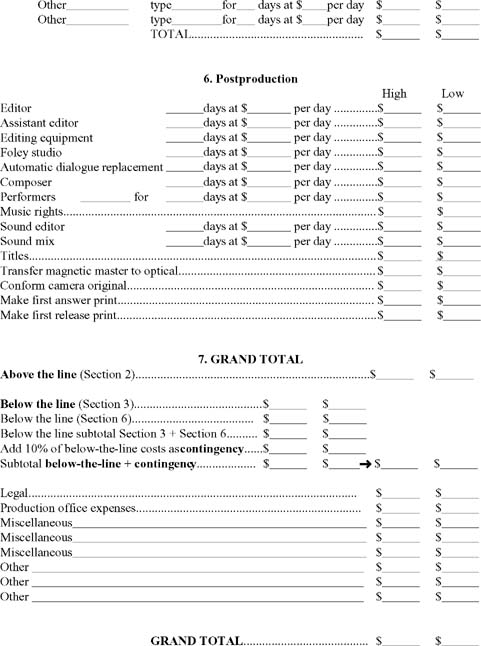

This is the moment when everything planned must be considered in terms of its cost, so the meeting involves a rough budget based on known schedule, locations, equipment, crew, and artists (Figure 27-1). It is good to consider higher and not just the lowest likely figures because the total for a film in which the

higher figures prevail can be a shock. It's good to confront this while you can still make adjustments.

There are a number of component calculations leading to the budget, the most significant being the number of locations and days spent shooting at each. Software exists for simple budgeting, but the industry favorite is Movie Magic™, an all-encompassing (though expensive) software package that provides tools to break down the script, turn it into a schedule, and arrive at a budget based on all the variables you enter. The beauty of a relational database of this magnitude is that any change anywhere, such as in script, rates, or scheduling, will immediately be reflected everywhere that it matters. You can also use the software to keep tabs on daily cash flow so there need be no unpleasant surprises hiding in the accounts department. You can see descriptions and reviews of different software for screenwriting, budgeting, and scheduling at www.writersstore.com, which also lists tutorials and manuals on how to get the most out of the software. Most people will need something akin to a producer's training to make proper use of the software.

Budget issues divide into above-the-line and below-the-line costs. The line is the division between preproduction and beginning production. So:

| Above-the-Line costs: | Story rights |

| Screenplay | |

| Producer's fee | |

| Director's fee | |

| Principal actors' fees |

____________________________________________“The Line”

Below-the-Line costs: |

Production unit salaries |

Art department |

|

Salaries |

|

Sets and models |

|

Props and costumes |

|

Artists (other than those above) |

|

Cast, stand-ins, crowd |

|

Studio or location facility rentals (with location and police permissions) |

|

Film or video stock |

|

Laboratories |

|

Camera, sound, and other equipment |

|

Power |

|

Special effects |

|

Personnel |

|

Catering, hotel, and living expenses |

|

Social Security |

|

Transportation |

|

Insurance |

|

Miscellaneous expenses |

|

Music |

|

Postproduction |

|

Publicity |

Indirect costs include finance and legal overhead costs. The pertinent questions are:

- How much does the production have in the bank?

- What is still to come?

- Using the projected shooting schedule, what will the film cost?

- Are there enough funds to cover projected costs?

- Are more funds needed?

- Can savings be made?

- Can any shooting be delayed until funds have been assembled?

Many factors lie behind arriving at a budget and its attendant cash flow forecast, not the least of which is what medium you are going to originate the film in. This is probably an early decision, but the final word is cast at the production meeting. Be aware that all movie budgets include a contingency percentage, usually 4% or more of the budget, which is added on to cover the unexpected, such as equipment failure, reshooting, and so on.

DRAWING UP AN EQUIPMENT WANT LIST

Learn as much as possible about the special technical requirements of the shoot so you, your DP, and your PM can decide what costs are truly justified. Some extra items turn out to be lifesavers; others just cost money and never get used. Keep in mind it's human ingenuity and not just equipment that makes good films.

How the film looks, how it is shot, and how it conveys its content to the audience are decisions that affect your equipment needs, but these decisions are about the form of the film and need to be made organically from the nature of the film's subject. Plan to shoot as simply as possible, choosing straightforward means over elaborate ones. The best solutions to most problems are elegantly simple.

With anything to be shot on film and edited digitally, your camera original must carry KeycodeTM or it cannot be conformed at the end to the edit decision list. Two good sources of information at every level are Kodak's student program, reachable through www.kodak.com/go/student and DV Magazine at www.dv.com for up-to-date information and reviews on everything for digital production and postproduction. Kodak has every reason to want people to continue using film and provides superb guidance in its publications and Web sites, which are prolific and as labyrinthine as you would expect of an organization with so many divisions.

Testing and repair equipment: When the time comes to check out equipment, never leave the checkout point without putting all the equipment together and testing that absolutely everything functions as it should. Make sure you have spare batteries for everything that depends on a battery and extra cables, which have a habit of breaking down where the cable enters the plug body. Carry basic repair equipment, too: screwdrivers, socket sets, pliers, wire, solder and soldering iron, and a test meter for continuity and other testing.

ACQUISITION ON FILM

Major equipment needs hinge on what image format you will use to shoot. Using the traditional film camera means a fairly straightforward (if long and expensive) equipment list. Film captures the best image quality, has a usefully limited depth of field, can be shown in any cinema in the world, and can be transferred to any video format—at a price. It requires heavy funding at the front end when you buy stock and will be expensive to process and make prints. Anybody experienced enough to light and shoot in film will probably know where to get the equipment and how much it will cost to carry what you need for the days that you need it.

16mm shoot: If you have quiet interiors, be sure to get a quiet camera. Old cameras can sound like coffee grinders, and it's a myth that they have a camera noise filter in postproduction. Be aware that the small formats magnify any weave or jiggle, and this shows up dramatically with titles or overlays.

Super 16mm shoot: Find someone who has recently and successfully completed the chain of production. Remember that Super 16 camera original has a different aspect ratio and runs on different sprockets in the lab. Not many labs can handle and print it. Are you going to strike workprints or have the camera original transferred to tape? Who's going to do it and for how much?

35mm shoot: Especially if you shoot in 35mm Panavision (Figure 27-2) you will need the appropriate camera support, probably a dolly with its own rails. If you want to do any handheld shots, you will need a Steadicam™ and someone very strong who is experienced in using it.

ACQUISITION ON VIDEO

The limitation of inexpensive digital cameras is that they have small imaging chips and a correspondingly large depth of field. This gives a typically flat image in which everything is in the same degree of focus. These cameras are also hard to control and have sloppy lenses. Being miniature, many features, such as white balance or sound recording level, can only be accessed by laboriously tapping your way through a menu. When your work is in NTSC you must make a special choice concerning timecode. NTSC is the American video recording standard, and the acronym stands for the National Television Standards Committee that invented it. PAL (Phase Alternate Line) is the standard common in Europe, and each is formulated to work at a different frame rate that is based on either 60 cycles per second alternating current frequency (NTSC) or 50cps (PAL). Working in NTSC requires that you choose whether to use drop frame or non-drop frame timecode. Drop frame removes a digit every so often so the recorded timecode remains in step with real time. It usually isn't important, but you must stay consistent through the production as it affects the editor. Electronic menus have a nasty propensity for somehow getting changed without anyone noticing. A professional camera is large, has external setting knobs and switches instead of menus, and the camera assistant can periodically run an eye over the settings—impossible with internal menus. Professional cameras also have a slot for a

memory stick, a solid-state memory the size of a credit card that can hold all the camera settings used to get a particular look. This can save a great deal of time.

Digitally recorded sound is most unforgiving if you over-modulate during recording. Another hassle is focusing the camera. Without manual control, you are often reliant on either setting a fixed distance in advance or letting the automatic focus do what it will. This simply focuses whatever is in the center of frame, no matter what your compositional balance or where you want the audience to look. So manual focusing and manual sound level adjustment are at a premium and usually come with the more advanced cameras only.

Medium of origination: Depending on how high you've set your sights, you may shoot with a modest digital video (DV) camera, with Digital Betacam, or in high definition (HD) using the Sony CineAlta system. If you expect to transfer your edited video final to film for theater projection, the cost must be determined. Each stage of the production has its own price. A great advantage of shooting digitally is that you don't have to change film magazines every 10 minutes of shooting, as you do with film. Cassettes last anywhere from 20–60 minutes, and this keeps everyone focused for longer periods. Typically, digital features are shot in the region of 20–30% less scheduled time than film. This is because the camera runs longer, needs less maintenance (there is no film gate to collect dirt), is light and quick to move, and needs less overall light.

DV origination for eventual film transfer: For this you may use a tried and true Canon or Sony DV camera, or perhaps a switchable camera offering a choice of frame rates like the Mini DV Panasonic AG-DVX100 (Figure 27-3). This manual or automatic control three-chip camera records at either 30 frames per second (fps) or 24p (which is shorthand indicating 24fps, progressive scan mode) that transfers well to film. To explain this: The video frame is normally made up of two passes or scans, one recording the odd lines, the other interlacing the even ones. A progressive scan records the entire frame in one pass before moving on to the next frame. This is closer to the film process and produces full-definition frames that are simpler to transfer to film. The camera also has two professional Cannon or XLR sound inputs at microphone or line levels, the usual Firewire or IEEE1394 socket for digital transfer to and from a nonlinear (NLE) system, and a special function for shooting that emulates film gamma range. Most valuable are the large color viewfinder; manual controls for audio volume, zoom, iris (aperture), and focus; and the 48-volt phantom power supply needed by some professional microphones.

High definition video: This video standard has twice the picture cells or ‘pixels’ of American 720 pixel DV and rivals 35mm film in picture quality. The Sony CineAlta HDW-F900 (see Chapter 1, Figure 1-1) has four digital sound channels, can shoot interlaced or progressive scan, and has a variable frame rate that allows you to shoot fast or slow motion, something normally attainable only in postproduction with video. In common with all professional-level cameras, its features, including follow-focus, are as fully controllable as a 35mm camera's. George Lucas, after shooting Star Wars Episode II using CineAlta cameras, said, “I think I can safely say I'll never shoot another film on film.”

Video to film transfers: Be aware that video to film transfers from 30fps video (NTSC system) are very expensive. A timebase has to combine the interlaced frames, then do a step-printing operation to render 30fps of video as 24fps of film. A 24p or PAL 25p video camera neatly obviates this. 24p is the contraction of fps or frames per second, and also implies progressive scan.

PAL system compared with NTSC: By shooting in the European PAL video standard you gain some advantage in acuity because the PAL image has more lines of resolution. PAL also transfers its interlaced (or better, progressive scan) 25fps more directly to film. However, when 25fps is projected at 24fps, the 5% speed change lowers the pitch of everyone's voice marginally and produces a 5% longer film. Why do PAL and NTSC have different frame rates? Most countries have a 220–230 volt with 50-cycle (or Hertz) alternating current. PAL's frame rate of 25fps is a straight division of 50Hz. The United States still uses Thomas Edison's legacy of 110 volts at 60Hz, so NTSC's 30fps is a division of the United States' 60Hz.

SOUND

Where will you record sound? In the video camera? In a separate DAT or analog Nagra recorder? If you shoot analog, how will sound be resolved and transferred for syncing later with its video picture? How many channels will you need to record? How will you mike each different situation? If you are using radio mikes, will you carry wired mikes as backup? What kind of clapper board will you use if you are shooting double system? What special thought has been given to sound design that the sound crew should be aware of? What effects or atmospheres are not obvious in the script and must be found or concocted during location shooting?

POSTPRODUCTION

Whatever origination you use will need the appropriate postproduction setup, from a $3,000 Macintosh computer with Final Cut Pro at the low end to a $225,000 Discreet Smoke HD or $300,000 Avid|DS HD postproduction rig at the high end. The length of the movie, the amount of coverage, and whether there are any special effects will have a profound effect on the postproduction schedule. Don't forget the audio stage, when the film is put through a ProTools software suite and the final track is mixed, possibly in a studio with a large theater costing hundreds or thousands of dollars a day.

CAUTION

If a software or camera manufacturer recommends particular associated equipment, follow the recommendation to the letter. There's a good reason. Before you commit to any of the links in a production chain, you must be 100% certain that all the links work together. For instance:

- Digital tapes shot on Sony equipment may not interface properly with other equipment.

- Panasonic may not have identical recording specifications.

- If you shoot in PAL, check that your computer software is not limited to NTSC or vice versa.

- If you edit in PAL in an NTSC country, you will need a DVCAM multi-standard player and recorder (Figure 27-4).

- Your film lab may not be able to do a 25fps transfer to film.

- You may have a problem transferring 25fps sound to your 24fps editing rig.

- If you mix and match equipment, each manufacturer or supplier will think the other equipment is to blame for the malfunction. Following one manufacturer's recommendations means you can expect to get their ear if anything goes wrong.

- For the same reason, always plan to have your processing lab conform the film prior to answer printing. If you use an outside service and the negative is scratched, the lab will blame the conformer who edits the negative to conform with the workprint or edit decision list (EDL), and the conformer will blame the lab.

Know and understand each stage's process. For any problems you must have definitive answers before you commit. When you seek advice, talk with those who have already done what it is you want to do, then use exactly the recommended equipment and procedures.

EQUIPMENT LISTS

At the production meeting, everyone brainstorms about what they need. Make lists and do not forget to include basic repair and maintenance tools. Some piece of equipment is bound to need corrective surgery on location.

Over-elaboration is always a temptation, especially for the insecure technician trying to forestall problems by insisting on the “proper” equipment, which always proves to be the most complicated and expensive. Early in your directing career you will be trying to conquer basic conceptual and control difficulties, so you probably have little use for advanced equipment and cannot afford the time it takes to work out how to best use it. At a more advanced level, sophisticated equipment may actually save time and money. Expect the sound department in particular to ask for a range of equipment so they can quickly adapt to changed lighting or other circumstances. This within reason is legitimate overkill.

If any of your crew are at all inexperienced, ask them to study all equipment manuals beforehand; these contain vital and often overlooked information. Make sure you carry equipment manuals with you on location. At the end of this book is a bibliography with more detailed information on techniques and equipment.

Do not be discouraged if your equipment is not the best. The first chapters of film history, so rich in creative advances, were shot using hand-cranked cameras made of wood and brass.

PRODUCTION STILLS

Someone should be equipped to shoot 35mm production stills throughout the high points of the shooting. Ideally you would use a good still photographer, but it may have to be someone with intermittent duties, such as a gaffer or electrician, who has an acceptable eye for composition. Stills seem unimportant, but they prove vital when you need to make a publicity package for festivals and prospective distributors. The director should set a policy on shooting stills so everyone knows they are important and will freeze on command while a still is taken. If time permits, the director or DP may be the best person to take the stills because pictures should epitomize the subject matter and approach of the movie, and act as a draw in a poster.

SCHEDULING THE SHOOT

A director needs to be familiar with the details of the organization and scheduling that make filming possible. Scheduling is normally decided by the director and the PM and double-checked by principal crewmembers, in particular the script supervisor and the DP. Excellent scheduling and budgeting software exists so that anyone with a computer can do a thoroughly professional job, as mentioned previously. Movie Magic™ is the film industry's choice of software package that will handle contracts, scheduling, and budgeting (you can see a range of software at www.filmmakerstools.com with a range of prices).

Regarding the schedule, you will often have to make educated guesses because no film is ever quite like any other and there are few constants. Because time inevitably means money, your schedule must reflect your resources as well as your needs. Take into account any or all of the following:

- Costs involved at each stage if hiring talent, equipment, crew, or facilities (use Movie Magic or other reputable software, or see basic budget form in Figure 27-1)

- Scenes involving key dramatic elements that may be affected or delayed by weather or other cyclical conditions

- Availability of actors and crew

- Availability of locations

- Relationship of locations and travel exigencies

- Availability and any special conditions attaching to rented equipment, including props

- Complexity of each lighting setup and power requirements

- Time of day, so available light comes from the right direction (take a compass when location-spotting!)

LOCATION ORDER

Normal practice is to shoot in order of convenience for locations, taking into account the availability of cast and crew. During a shoot, lighting setups and changes take the most time, so a compact schedule conserves on lighting changes and avoids relighting the same set. Lighting usually requires that you shoot wide shots (which may take all the light you've got) first and close shots later because these must match their wide-shot counterparts. For these reasons and more, it is highly unusual to shoot in script order.

The character and location breakdown (Figure 17-4) described in Chapter 17 shows which scenes must be shot at each location. It is normal that scenes from the beginning, middle, and end of the film may all be shot in the same location. This makes rehearsal all the more important if actors and director are to move authoritatively between the different emotional levels required. The scene breakdown also displays which characters are needed, and this, in association with the cost and availability of actors, influences scheduling.

SCRIPT ORDER

Some films may need to be shot in script order, particularly if director and cast are inexperienced or poorly rehearsed. Here are some such examples:

- Those depending on a graduated character development—like the king's decline into insanity in Nicholas Hytner's The Madness of King George (1995)—that calls for finely controlled changes by actors in the main parts

- Those depending on a high degree of improvisation might need to shoot in script order to maintain control over an evolving story line

- Those taking place entirely in interiors and that have a small, constant cast. Here there is no advantage to shooting out of scene order, so you might as well reap the benefits of sequential shooting

Whenever shooting in script order is impractical, the director, cast, and crew must be thoroughly prepared so that patchwork filming will assemble correctly.

KEY SCENES AND SCHEDULING FOR PERFORMANCES

Some scenes are so dramatically important that there will literally be no film should they fail. Imagine if your whole film hinges on a scene in which your naive heroine falls in love with an emotionally unstable man. It would be folly to shoot everything else trusting that your actors can make a difficult and pivotal scene work.

Key scenes must be filmed neither too early (when the cast is still green), nor too late (when failure might render wasted weeks of work). If the scene works, it will give a lift to everything else you shoot. If the scene bombs, you will want to work out the problems in rehearsal and reshoot in a day or two. You cannot commit to shooting the bulk of the film until this problem is solved.

Problems of performance should show up in rehearsals, but camera nerves may kick in, especially if the scene exposes the actor. Filming is only occasionally better than the best rehearsal, and often it is below it. The cast may feel more deeply during the first takes of a new scene, but strong feeling is no substitute for depth of character development. When cast members realize they must sustain a performance over several takes per angle and several angles per scene, they may also instinctively conserve on their energy level. Knowing this, you should shoot with an editing pattern in mind so you don't yield to the temptation to cover everything. Drawing the line between adequacy and wastefulness is hard for the new director, so it's best to err on the side of safety.

EMOTIONAL DEMAND ORDER

Scheduling should take into account the demands some scenes make upon the actors. A nude love scene, for instance, or a scene in which two characters get violently angry with each other should be delayed until the actors are comfortable with each other and the crew. Such scenes should also be the last of the day because they are so emotionally draining.

WEATHER OR OTHER CONTINGENCY COVERAGE

Schedule exteriors early in case your intentions are defeated by unsuitable weather. By planning interiors as standby alternatives, you need lose no time. Make contingency shooting plans whenever you face major uncertainties.

ALLOCATION OF SHOOTING TIME PER SCENE

Depending on the amount of coverage, the intensity of the scene in question, and the reliability of actors and crew, you might expect to shoot anywhere between 2 and 4 minutes of screen time per 8-hour day. Traveling between locations, elaborate setups, or relighting the same location all greatly slow the pace. Many directors allot setup time for the mornings and rehearse the cast while the crew is busy, but this is unlikely to work as well outside a studio setting.

UNDER- OR OVERSCHEDULING?

A promising film may also be sabotaged by misplaced optimism rather than any inherent need to save money. Consider the following:

- Schedule lightly during the first 3 days of a shoot. Work may be alarmingly slow because the crew is still developing an efficient working relationship with each other.

- You can always shorten a long schedule, but it may be impossible to lengthen one originally too short.

- Most non-professional (and some professional) units try to shoot too much in too little time.

- A cast and crew working 14-hour days become fixed on just surviving the ordeal.

- Artistic intentions go out the window as a dog-tired crew and cast work progressively slower, less efficiently, and less accurately, and as tempers and morale deteriorate.

The first half of the shoot may fall seriously behind if the AD and PM do not apply the screws and keep the unit up to schedule. Not only does an inexperienced crew start slowly and over time get quicker, they also tend to reproduce this pattern during each day unless there is determined progress-chasing by the DP and AD.

AGREEMENT ON BUDGET AND SCHEDULE

By the end of the meeting everyone should have agreed on equipment and schedule. The PM can make a detailed budget and the 1st AD can go to work on preparing the call sheets.

CAVEATS

Make “test and test again” your true religion. Leave nothing to chance. Make lists, and then lists of lists. Pray.

GOLDEN RULE #1: EXPECT THE WORST

Imagination expended darkly, foreseeing the worst, will forestall many potentially crippling problems before they even take shape. That way you equip yourself with particular spares, special tools, emergency information, and first aid kits.

Optimism and filmmaking do not go together. One blithe optimist left the master tapes of a feature film in his car overnight. The car happened to be stolen, and because there were no copies, a vast amount of work was transformed instantly into so much silent footage.

The pessimist, constantly foreseeing the worst and never tempting fate, is tranquilly productive compared with your average optimist.

GOLDEN RULE #2: TEST IT FIRST

Arrive early and test every piece of equipment at its place of origin. Never assume that because you are hiring from a reputable company, everything should be all right. If you do, Murphy's Law will get you. (Murphy's Law: Everything that can go wrong will go wrong.) Be ready for Murphy lurking inside everything that should fit together, slide, turn, lock, roll, light up, make a noise, or work silently. Murphy relatives hide out in every wire, plug, box, lens, battery, and alarm clock. Make no mistake; the whole bloody clan means to ruin you.

COST FLOW AND COST REPORTING

The goal of budgeting is to make a cost flow projection. During production the PM prepares a daily cost report:

- Cost for period

- Accumulated cost to date

- Estimated cost to complete

- Final cost

- Over or under budget by how much?

The object is to bring the production in on cost and in the agreed time.

INSURANCES

Depending on the expense and sophistication of a production, it will carry some or all of the insurance. Even film schools, mindful of the litigiousness of John Q. Public, sometimes make their students carry insurance coverage.

Preproduction indemnity: Covers costs if production held up due to accident, sickness, or death during or before production

Film producer's indemnity: Covers extra expense being incurred due to a range of problems beyond the producer's control

Consequential loss: This covers increased production costs due to the loss or damage to any vital equipment, set, or prop

Errors and omissions: Covers claims against intellectual property (copyright, slander, libel, plagiarism, etc.) or other mistakes

Negative insurance: Covers reshooting costs due to loss or any damage to film negative

Employer's liability: Mandatory insurance that may be required for protection of employees

Public or third party liability: Insures against claims for property damage and personal injuries

Third party property damage: Insures against claims brought against film company for damage to property in their care

Equipment insurance: Covers loss or damage to hired equipment

Sets, wardrobe, props: Covers costs resulting from their loss or damage

Vehicles: Coverage for vehicles, particularly specialized vehicles, or those carrying costly equipment

Fidelity guarantee: A financial backer's requirement to guard against infidelity—the budget being embezzled

Union and other insurances: Film workers are often union members, and their union stipulates what coverage is necessary when they are hired. Special insurances are often required when working abroad under unusual health or other conditions.

CREW CONTRACTS

Once all details have been decided, the PM sends out letters of engagement to secure the services of crewmembers. These describe the job, the salary, working hours, and length of contract. There will be a number of clauses stipulating rights and expectations on either side, as in any contract. Any union requirements must be followed scrupulously, if trouble later is to be avoided.

PRODUCTION PARTY

Once the crew is known and actors are cast, it is customary to have a production party. This acts as an ice breaker, bringing everyone together for the first time. One of the pleasant aspects of working in the film business is that over the years you work with the same people every so often. Because everyone is freelance, everyone is happy to work. Production parties are therefore very pleasant and constructive occasions.

CHECKLIST FOR PART 5: PREPRODUCTION

The points summarized here are only the most salient or those that are commonly overlooked. To find them or anything else, go to the Table of Contents at the beginning of this part, or try the index at the back of the book.

Deciding on Subjects:

- Choose your subject carefully; you are going to live with it for a long time.

- Through your film, be concerned for others.

- Choose a subject and issues you would love to learn more about.

Questions When Assessing a Script:

- How behavioral and visually cinematic is it?

- How well would it play with the sound turned off?

- Whom did you care about and find interesting?

- Is the plot credible, or can it be made so?

- What is the screenplay trying to do, and how is it going about it?

- In each scene decide what each character wants, moment to moment. What do they do to get it?

- What stops the character and how does he or she adapt to each obstacle?

- Are the obstacles intelligently conceived to put the characters to the test?

- Are all characters integrated and multifunctional or are some convenience characters who exist only to solve particular situations?

- Who grows and develops in the script and who remains only “typical?”

- What do you learn from making a step outline?

- What is the screenplay's premise?

- What are the screenplay's thematic concerns, and how effectively does it deal with the main one?

- What does making a flow chart for the final reveal, after you've named the function of each scene?

- What does a scene, character, location breakdown reveal?

- Time the film; does the film's story content merit the time it takes onscreen?

- What problems emerge when you make an oral summary (a pitch) to a listener?

Script Editing

Plot and Character:

- Relate story line to basic dramatic situations and the hero's journey archetypes.

- Decide from similar stories whether characters can be made more effective.

- See if vital information comes early enough and whether any reinforcement is needed.

- if it's spoken and too noticeable, hide it within action.

Action:

- How well would the film play if it were silent?

- Try reconfiguring dialogue scenes to play out as behavior instead of dialogue.

- See what actions might better reveal each character's inner life and qualities.

Dialogue:

- Drop lines wherever possible.

- Convert discussion into behavior when possible.

- Tighten, compress, and simplify remaining lines.

- Make sure the dialogue is in the character's own vernacular.

Scenes:

- Mark beats and critically examine the working of each dramatic unit.

- See whether each scene can create more interesting questions in the audience's mind.

- See whether delay before these concerns are answered is too short or too long (often it's counterproductively short).

- Eliminate scenes that repeat information or that fail to advance the story (get this information from your flow chart).

Dramaturgy and Visualization:

- Decide whether convenience characters should be eliminated, amalgamated, or made properly functional.

- From your flow chart assess how well the screenplay “breathes” between different kinds of scenes, and consider transposing to improve variety.

- Consider radical adjustments if parallel works and archetypes promise a better thematic impact.

- Check for evocative imagery that could play a special part (visual leitmotifs, foreshadowing, symbolism, visual analogies, etc.).

Check That the Screenplay's World Is:

- Authentic

- Adequately introduced if it's unfamiliar

- Making full use of its connotations

- Write brief character descriptions; advertise appropriately.

- Actively search out likely participants for audition.

- Pre-interview on phone before giving an audition slot.

- Thoroughly explain time and energy commitment.

- Ask actor to come with two contrasting monologues learned by heart.

First Audition:

- Receptionist chats with actors and has them fill out information form.

- See actor's monologues and classify his or her self-image.

- Look for acting with whole body, not just face.

- Listen for power and associations of actor's voice.

- Ask yourself, “What kind of character would I get from this actor?”

- Thank actors and give date by which decision will be communicated.

Decisions Before Callback:

- Call each actor and inform whether he or she is wanted for callback.

- When you must reject, tell each actor something positive about his or her performance.

- Avoid casting people for their real-life negative traits.

- Carefully examine videotapes now and later for actor's characteristics relayed from the screen. Your impressions and intuitions here are everything.

Callback:

- Combine promising actors in different permutations.

- Have actors play parts in different ways to assess their capacity for change.

- Test spontaneous creativity with improvisations based on the piece's issues.

- Redirect second version of improv to see how actors handle changes.

Consider Each Actor's:

- Impact

- Rhythm and movements

- Patterns of development

- Quickness of mind

- Compatibility with the other actors

- Ability for mimicry (accents, character specialties, etc.)

- Capacity for holding onto both new and old instructions

- Intelligence

- Temperament

- Type of mind

- Commitment to acting and to this particular project

- Concentration and attention span

Shoot camera test on principals; consider confronting actors with your reservations before casting. Thank all for taking part and arrange date for notification.

Developing the Crew:

- Cast crew carefully because they create the work environment.

- Shoot tests even with experienced members.

- Inquire into crewmembers' interests and values.

- Check reputation in previous collaborations.

- Assess flexibility, dependability, realism, and commitment to project.

- Clearly delineate reporting lines.

- Begin crew relationships formally. You can become more informal later.

Script Interpretation:

- Check all points under “Script Editing” section.

- Determine the givens.

- Convert conversation into action that would relay the story without sound.

- Make sure screenplay establishes facts and necessary values for audience.

- Define point of view, subtexts, and characters' hidden pressures for each scene.

- Graph dramatic pressure changes for each scene, then string them together to graph out dramatic development for the film as a whole.

Rehearsal:

- Actors study the piece and make character biographies, but do not yet learn lines.

- Director and actors break scene into dramatic units, with clear developmental steps within each unit.

- Director encourages the search for action and movement at every stage.

- Director meets principal actors singly to discuss their characters.

- Expect actors to problem-solve.

- Keep notes during each run-through.

- Actors must play the scene, not the lines.

Focusing Thematic Purpose with the Players:

- Discuss backstory and purpose of the piece with cast.

- Discuss subtext for key scenes and what it reveals about each of the characters.

- Develop a hierarchy of themes so you know what is most important.

- Tackle key scenes first.

- Thereafter point out what links these scenes.

- Deal only with top level of a scene's problems at each pass.

- Work on motivations.

- Develop possible actions.

- Find and characterize the beats.

- Develop special actions for the beat points.

- Within each dramatic unit, figure out the stages of escalation that lead to the beat.

- Rehearse on location or thoroughly brief actors on particularities of location.

- Now actors can learn their lines!

Rehearsal without the Book:

- Dialogue should be a verbal action that seeks an effect.

- Film actors have no audience; they should be indistinguishable from real people coping with a real situation.

- When an actor keeps losing focus, figure out the obstacle.

- Staying in character comes from staying appropriately busy in mind and body.

- Focus leads to relaxation.

- Watch your actor's faces and bodies for telltale signs of inappropriate tension.

- Authentic physical action during performance liberates authentic emotion.

- Use improv to set level of focus to be matched when you work with the text.

- Give local, specific, positive goals for actors to reach.

- Characters' actions should generally seek an effect in other characters.

Review the Taped Scene:

- Does it communicate effectively when viewed without sound?

- Is the cast using space effectively?

- Are characters fully using their physical surroundings?

- Can you see the characters' visions, memories, and imaginations at work?

- Does each character constantly pursue his or her own agenda?

Thinking Ahead about Coverage:

- Set a timing limit for the scene and keep tabs on rehearsal timings.

- Prepare cast for blocking changes should exigency so require (it often does).

- Cut dialogue or action to stay within timing goals.

- Note intentions for each scene while your memory is fresh.

- What era and what world do the characters live in?

- What is that world's palette?

- What are their characteristic clothes and colors?

- How do the characters contrast with each other, and how is this reflected in costuming?

- What objects, furniture, and surroundings are peculiar to the characters?

- What is the succession of moods in the film, and how is this reflected in lighting and color schemes?

- What is the color progression through the film?

Production Meetings:

- All locations scouted?

- Shooting schedule contains bad weather coverage?

- Shooting order takes into account key scenes and emotionally demanding ones?

- Budget worked out and contains contingency percentage?

- Equipment want lists prepared and budgeted?

- Production origination and postproduction methods are worked out and budgeted?

- All equipment is justified?

- Arrangements have been made to shoot production publicity stills?

- Cost flow reporting is organized?

- Necessary insurances are arranged?

- Permissions for locations and police permits for exteriors have been obtained?

- Crew contracts are ready to issue?

- Production party has been scheduled?