CHAPTER 35

DIRECTING THE ACTORS

Directing a film means carrying a detailed movie in your head that you have broken into component parts, and then manipulating cast and crew until you get the parts you want. Crew and cast know this, and when they turn to you expectantly, they are asking, “Did you get what you wanted?” You have to know, one way or the other. Naturally, along the way, other possibilities intrude, so the movie you are assembling in your head is constantly evolving and adjusting to opportunities and disappointments.

During shooting, a supportive, enthusiastic cast and crew will endure and triumph together, but under the best of conditions this will be a stressful time for everyone. It's a period of high concentration for the crew, all of them trying to do their best work, and for you it is a time of occasional euphoria or despair. Unlike anyone else, the director must simultaneously scan many people's work. Hardest to fulfill is your actors' need for your feedback while you are also directing the crew.

SENSORY OVERLOAD

The director's occupational hazard is sensory overload. In a typical take, while you watch the actors keenly, you will also hear a lamp filament humming and a plane flying nearby. Can the sound recordist hear them? Insulated inside her headphones, she only returns your look questioningly with a silently mouthed, “Huh?” Next you see a doubtful camera movement, and wonder if the operator will call, “Cut!” Your heroine turned the wrong way when leaving the table, and your mind races as you figure out whether it can possibly cut with the longer shot. Now, to further boggle your mind, the camera assistant holds up two fingers, signifying only two minutes of film left. At the end of the take your cast looks at you expectantly. How was it? Of course you hardly know. If you are working on tape or have a video assist, you could replay their work, but doing that too often would double the shooting schedule.

More practical is to be ruthless about how you will use your energy. A competent crew will catch all the sound, camera, and action problems and report anything you need to rectify. If you have a union crew, who come from a system that produces highly reliable workers, you can delegate without fear. But if you draw from a casual labor system, you are probably using freelancers who generally lack experience. A film school produces some quite brilliant people, but their lack of practice results in a higher number of mistakes and omissions. No way around it: You get what you pay for, and when you can't pay, you have to work twice as hard.

ACTORS NEED FEEDBACK

From experience in school and theaters, actors come to depend on audience signals. Filming is without such signals, for the director is the sole audience and cannot give feedback during a take. Afterward you must try to give each actor the sense of closure normally acquired from an audience.

Actors are not fooled by empty gestures. Your brain has been running out of control trying to factor in all the editing possibilities that make the last performance even usable, and now you must say something intelligent to your trusting players, each of whom is (and must be) self-absorbed and self-aware. You manage something and the cast nods intently.

Now your crew needs you, and the actors are already asking, “What are we doing next?” The production manager is at your elbow demanding confirmation for the shooting at the warehouse next week. The warehouse people are on the phone, and they sound testy.

So there you have it: The true glamour of directing is walking around faint from lack of sleep, feeling that your head is about to explode.

DELEGATE

The solution lies in setting priorities and delegating as much as possible of the actual shooting to the director of photography (DP), who directs the crew. Your assistant director (AD) and production manager (PM) should also take much of the logistical work off your shoulders.

ACTORS' ANXIETIES AT THE BEGINNING

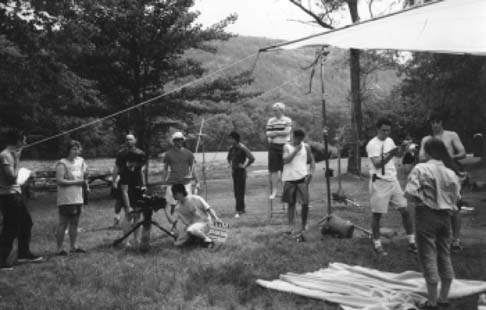

PREPRODUCTION PARTY

Bring cast and crew together for a picnic or potluck party before production begins to break the ice.

WARN ACTORS THAT SHOOTING IS SLOW

Thoroughly warn actors that all filming is slow. Even a professional feature unit may only shoot 1–4 minutes of screen time per 8-hour day. Tell them to bring good books to fill the inevitable periods of waiting.

BEFORE SHOOTING

The time of maximum jitters and minimum confidence for the actors is just before first shooting. Take each aside and tell him or her something special and private. It should be something sincere and personally supportive. Thereafter that actor has a special understanding to maintain with you. Its substance and development will reach out by way of the film to the audience, for whom you are presently the surrogate.

TENSION AND ITS CONSEQUENCES

Whatever level of performance was reached in rehearsal now comes to the test when shooting begins. Actors will feel they are going over Niagara Falls in a barrel. Wise scheduling puts the least demanding material early as a warm-up. In the first day or two there will be a lot of tension, either frankly admitted or displaced into one of the many behaviors that mask it (see Chapter 20: Actors' Problems). Try not to be wounded or angered; if someone is deeply afraid of failing a task, it is forgivably human to demote the work's importance. It does not mean actors are deficient as a breed (the belief of many film technicians) but rather that they are normal people temporarily succumbing to vulnerability and self-doubt. Having no equipment to hide behind like the crew, actors can easily feel exposed and humiliated. Filming is incomprehensibly slow, and the crew, enviably busy with their gadgets, seem removed and uncaring. Your appreciation and public recognition given for even small achievements, and your crew's astute catering work, will work wonders for morale.

GETTING INTO STRIDE

As the process settles into a familiar routine, anxieties subside, and actors fall in with the pace and demand of the shooting, arriving eventually at pride in being a member of the team. Performances improve so much that you wonder about the usability of the earlier material.

DIRECTING

While actors are visibly working their way through a labyrinth of strong feelings, the director must suffer any similar crises in silent isolation. Because cast members invest such trust in their director, you must play the role of the all-caring, supportive, and supremely confident parental figure.

The poor novice is racked with uncertainty about whether he or she even has the authority to do the job. How do you wield authority when you feel like a fraud? The secret to success involves acting, so you play at being confident a role the whole film unit wants to believe. Help yourself by limiting the area you oversee, by being better prepared than anyone, and by keeping everyone busy. Your major responsibility is to the cast, and your authority with them rests on how well you can tell each what they have just given and then point the way forward. This is your central function, so divest yourself of anything impeding it.

Both cast and crew are apt to try your patience and judgment. It is the fate of leaders to have their powers challenged, yet behind what seems like a sparring and antagonistic attitude may lurk a growing respect and affection. The unaccustomed parental role—supporting, questioning, challenging—may leave you feeling thoroughly alone and unappreciated. You are Authority, and many creative people have their most ambivalent relationships with such figures.

For your cast, “my director” and the other actors may be the most important people in their lives, allies with whom to play out complex and personal issues that involve love and hate and everything else between. This is just as legitimate a path of exploration for an actor as it is for any other artist. Finding a productive working relationship with the subtle personalities of your actors is really discovering how best to use your own temperament. There are no rules because the chemistry is always different and changing. Always aim to be respected rather than liked. Liking comes later if things go well. Never confuse the roles of friend and director. A director directs and stands implacably at the crossroads to all the important relationships that go into the film's making. You must do whatever it takes to keep everyone focused on the common enterprise. There is no set way to handle this except to demand implicitly that everyone remain more loyal to the project than anything else in the world. Professionals understand this—the rest do not.

DIVIDING YOURSELF BETWEEN CREW AND CAST

The director of a student production is usually using an untried crew and feels justifiably that every phase of the production must be personally monitored. But to adequately direct the human presence on the screen, you must entrust directing the crew to the DP and the AD. You cannot afford not to know how the material will work on the screen, and this will take all of your attention.

Directing is easier (though hardly less stressful) for those arriving via professional work in one of the allied crafts because long years of industry apprenticeship teach people how to work in a highly disciplined team. Without this conditioning, the student director and crew are in a precarious position, but if Truffaut's Day for Night (1973) is as representative as I think, a lowering of ideals during shooting is a common experience.

DAILY ORGANIZATION

Be sure everyone is well prepared. A smoothly running organization signals professionalism to cast and crew and is vital if low-paid (or unpaid) people are to maintain confidence in your leadership. This means preparing the following:

- Printed call sheets for cast and crew well in advance

- A map of how to get to the location

- A list with everyone's cell phone contact numbers in case of emergency

- Floor plans for camera crew

- A pre-established lighting design

- Tricky camera setups rehearsed in advance

- Correct props and costumes ready to go

- Scene coverage thoroughly worked out with DP and script supervisor

- AD has lists of everything so you carry nothing in your head and nothing gets forgotten

RUN-THROUGH

You will have to run through the action of the shot for the camera crew, who are interested at this stage in resolving framing and lighting problems. The DP may borrow crew members as stand-ins for lighting and movement checks so cast members aren't unnecessarily fatigued by the time the unit is ready to shoot.

BEFORE THE TAKE

As the crew finalizes the setup, take your cast aside and rehearse them intensively. Remind each actor of his or her character's recent past and emotional state on entering the scene. This is vital both as information and as implied support and may need to be repeated in a few words before every take. With you alone rests the knowledge of the prior scene's emotional level, and whether the new scene grafts naturally on to the old.

Your AD will quietly tell you when the setup is ready so actors can start with the minimum of waiting. Actors take their positions. The DP makes a last check that all lights are on and everything is ready.

AFTER THE TAKE

Immediately after calling “Cut!”:

- Tell the crew whether you are going for another take or a new setup.

- Go up to the actors and confidentially tell them how they did. This may simply be “Fine, everyone” or it may be more analytical. Any specific differences you note will reassure them that you are aware of what they are giving.

- If going for another take, brief each actor on what to aim for (whether the same or something new).

- Shoot before the collective intensity dissipates.

Sometimes a further take is necessary because of a technical flaw in sound or in camera coverage, but usually you want better or different performances. This may affect each actor in a group scene differently. From one you want the same good level of performance, from another a different emotional shading or energy level. Each actor needs to know what you expect.

Actors themselves will sometimes feel they can do better and will ask for another take. You must instantly decide whether that's necessary. If you think it is, you call, “We're going for another take. Roll camera as soon as possible.” While cast should always be allowed to improve, asking for just one more take can become a fetish or a manipulation of directorial decisions. Sometimes you must insist that the last take was fine and that you must move on. Actors' insecurity has a thousand faces.

FOR THE NEW SHOT

As soon as you have an acceptable take, brief the DP what the next shot is to be, and turn to the cast to explain what you need next. Give positive feedback about the last shot and provide preparation for the next. The AD may decide to take the actors aside to rest them as the crew roars into action changing the camera, set, lights, everything. Previously the cast had control—now they slip into obscurity as the crew collaborates in setting up a new shot.

DEMAND MORE OF ACTORS

The enemy in directing is your passive and gullible tendency to accept what actors gave as the best they could do. There is a lot of guilt at first when you are an audience of one. All these people are doing all this … for little old you! You want to please them, to thank them, to be liked by them. And you can't even react while they perform, to tell them how grateful you feel. You echo their need for approval with your need to be liked … It's an uncomfortable experience.

Try to instill in yourself the artist's creative dissatisfaction with every first appearance. Treat what you see as the deceptive surface of a deep pool, a reflective façade covering a teeming life underneath whose complexity will only be found by diving deeper. Treat each scene as a seeming beneath which hide layers of significance that only skill and aspiration can lay bare.

Rather than give your players different pass levels, concentrate on what they communicated. This will vary from take to take. You can say what you would like to try for next time and give additional input to individual players.

Always pushing for depth means expecting to be moved by the players, and sometimes it will happen strongly. You are tempted to make yourself be moved. This happens because you feel guilty that the cast is trying so hard and your own role is that of hard-to-please pasha. This is not the point; you must resist onlooker's guilt and allow yourself to be acted upon. If it works, it works; if it doesn't, ask why. Report to your cast what you felt and to what degree. When your players deliver real intensity, you are creating as you go, not simply placing a rehearsal on record.

Because you are working in a highly allusive medium, your audience expects metaphorical and metaphysical overtones. To draw us beneath the surface of normalcy, to get beyond externals and surface banality, and to make us see poetry and conflict beneath the surface, you will have to challenge your actors in a hundred interesting ways. These demands keep the cast and crew on their toes and make the work challenging and fascinating. You represent the audience, and actors work to please you. They want your approval because your demands personify their own gnawing sense of always somehow being capable of better. This dissatisfaction is as it should be. It may be accompanied on some people's part by an undertow of complaining. Emphasize the positive and think of the grumbling as the noise of the rigging in a ship pushed to capacity. Or think of dancers, so often in bodily pain. That pain comes from pushing themselves to the limit to make dance look effortless and wonderful. Your cast is in pain, too, so take it for what it is, and don't think you have to make anyone feel better.

WHEN THE SCENE SAGS

To put tension in a scene that threatens to subside into comfortable middle age, take one or more actors aside and privately suggest to each some small but significant changes that will impact other cast members. By building in little stresses and incompatibilities, by making sure cast members are working off each other, you can restore any tautness that has languished.

SIDE COACHING WHEN A SCENE IS BECALMED

When a scene goes static and sinks to a premeditated appearance, try side coaching to inject tension. This means you interpolate at a quiet moment in the scene a verbal suggestion or instruction, such as, “Terry, she's beginning to make you angry—she's asking the impossible.” Your voice injects a new interior process in the character addressed, but it will not work if your actors are caught by surprise. If they are unfamiliar with side coaching, warn them not to break character should you use it.

REACTION SHOTS

Side coaching is most useful when directing simple reaction shots. The director provides a verbal image for the character to spontaneously see or react to, or an idea to consider, and gets an immediacy of reaction by challenging the actor to visualize something new and face the unexpected.

Usually the best reactions are to the actual. If a character must go through a complex series of emotions while overhearing a whispered conversation, make it a rule that the other characters do a full version of their scene even though it is off camera. If, however, your character must only look through a window and react to an approaching visitor, her imagination will probably provide all that is necessary.

One way during casting to test an actor's imaginative resources is to give him or her a phone in order to improvise a conversation with another (imagined) person whom you specify. You should be unable to tell whether an actual person is on the other end or not.

Reaction shots are enormously important, as they lead the audience to infer (that is, create) a character's private, inner life. They also provide vital, legitimate cutaways and allow you, in editing, to combine the best of available takes. Never dismiss cast and crew from a set without covering the reactions, cutaways, and inserts for each scene. And always make certain the sound recordist has shot some presence track.

CRITICISM AND FEEDBACK

Be prepared for personality problems and other friction during shooting. Actors' preferences and criticisms that were expressed during rehearsal often surface more vehemently under duress. There will be favorite scenes and scenes the actors hate, scenes that involve portraying negative characteristics and even certain lines upon which an actor becomes irrationally fixated. One palliative in serious cases is to allow a take using the actor's alternative wording. Don't offer this until all

other remedies have been exhausted, and do it as a one-time-only concession, or your cast may all want to start writing alternatives.

As knowledge of each other's limitations grows, actors can become critical or even hostile to each other. Occasionally two actors who are supposed to be lovers take a visceral aversion to each other. Here, loyalty to the project and commitment to their profession can save the project from utter disaster. Filming makes intense demands on people, and a director must be ready to cope with everything human. You will learn hugely about the human psyche under duress, and this will make you a better director—and also a better human being! If this sounds scary, take heart. The chances are good that you and your cast will like each other and that none of these horror stories will happen to you—yet.

FROM THE CAST

Creative initiative cannot be limited to the director if the cast is to become a company. The cast may have criticism or suggestions in relation to the script, the crew, or yourself, the director. Acknowledge the criticism and if it is justified and constructive, act upon it diplomatically and without guilt. A wise director stimulates and utilizes the creativity of all the major figures in the team, aware that organic development and change will always be something of a threat to everyone's security, including his or her own.

When critical suggestions are incompatible with the body of work already accumulated, say so as objectively as you can. Remaining open-minded does not mean swinging like a weather vane. The best way to deflect impractical suggestions is to be so prepared and so full of interesting demands that everyone is too busy to reflect. This won't deter genuinely thoughtful and constructive ideas.

FROM THE CREW

Actors find the spectacle of dissent among the crew disturbing, so criticism by them should be discreet and kept completely from public view. Student crew members are sometimes unwise enough to imply how much better they could direct than the director and to publicly voice their improvements. This is an intolerable situation that must be immediately corrected. Nothing diminishes your authority faster than actors feeling they are being directed by a warring committee.

Guard against this situation by making sure that territories are clearly demarcated before the shooting starts. Anyone who now strays should be told privately and very firmly to tend his own area and no-one else's. When a crew member thinks he or she has a legitimate complaint, it should be routed through the DP.

There will be occasions when you have to take a necessary but unpopular decision. Take it, bite the bullet, and do not apologize. Like much else, it is a test of your resolve, and the unpopular decision will probably be the one everyone knows is right.

MORALE, FATIGUE, AND INTENSITY

Morale in both crew and cast tends to be interlocked. Giving appropriate credit and attention to each member of the team is the best way to create loyalty to the project and to each other. Everyone works for recognition, and good leadership trickles down. Even so, immature personalities will fracture as fatigue sets in or when territory is threatened. Severe fatigue is dangerous because people lose their cool and work becomes sloppy. Essentials can easily get overlooked, but careful and conservative scheduling can guard against this.

One simple insurance against failing morale is to take special care of creature comforts. Your production department should make sure that people are warm, dry, have bathrooms to go to, somewhere to sit down between takes, and food and drink. Avoid working longer than 4 hours without a break, even if it's only a 10-minute coffee break. From these primal attentions cast and crew infer that “the production” cares about them. Most will go to the ends of the earth for you when they feel valued.

PROTECT THE CAST

Everything that can weigh unnecessarily on the actors should be kept from them. Disputes or bad feeling among the crew should be scrupulously kept confidential. Actors are vulnerable to emotional currents, and their attention should remain with their work.

YOU AS ROLE MODEL

You are the director. Your seriousness and intensity set the tone for the whole shoot. If you are sloppy and laid back, others will outdo you, and no film may get made. If you demand a lot of yourself and others but are appreciative and encourage appropriate humor, you will probably run a tight ship. Your vision and how you share it will evoke respect in the entire team. People will follow an organized visionary anywhere.

Present any negative criticism you have as a request for a positive alternative.

USING SOCIAL TIMES AND BREAKS

During the shooting period, spend time (outside the actual shooting) with your cast. However exhausted you become, it is a mistake to retreat from the neuroses of your actors to the camaraderie of the crew. Instead, try to keep cast and crew together during meals or at rest periods. Frequently, while lunching or downing a beer after work, you will learn something that significantly complements or changes your ideas. Under good conditions, the process of filmmaking shakes out many new ideas and perceptions and generates a shared sense of discovery that binds crew and participants together in an intoxicating feeling of adventure. Conserved and encouraged, this sense of excitement can so awaken everyone's awareness that a profound fellowship and communication develop. Work becomes a joy.

AT DAY'S END

Thank people formally and individually at the end of each day's work. Respectful appreciation affirms that you take nobody for granted. By implication you are demanding that respect in return. Under these conditions, people will gladly cede you the authority to do your job.

WHEN NOT TO LET THE CAST SEE DAILIES

Under the usual pressured shooting schedule, show dailies only to make a point that can be made no other way. I once convinced a player that he was acting instead of simply being by showing him some surreptitiously shot footage of himself in spontaneous conversation. The contrast between this and him performing a scripted conversation was so striking that he abandoned his resistance to my judgment. This kind of revelation takes a negative approach and can easily backfire. Show footage cautiously and supportively only if you can get results no other way. The same procedure can be used with the actor of fragile ego who insists on projecting a rich and unnatural acting voice instead of his or her natural range. The worst consequence of showing dailies is that you end up with five cast members and six directors. At any time, actors may shift feelings of humiliation on to other cast members or the director and, in their anguish, seek control.

With familiarity, actors seeing themselves on the screen come to more or less accept how they appear, but the journey to equanimity can be long and rough. If you must go that route, get it over during the rehearsal period while they are learning to trust you, their director. Nobody will seek control if your cast trusts what you communicate. Most actors will say that their greatest pleasure comes from working with a strong director who demands much of them and is appreciative.

It is quite normal to show dailies only to the crew, and you should make no bones about doing this if you suspect that anyone in the cast will be undermined by it. Promise the cast a viewing of the first cut, if you like, to assuage their natural curiosity. By then they have given their performances, and however their image influences them will not jeopardize your film.