CHAPTER 42

WORKING WITH A COMPOSER

Composers are the last in the creative chain to be hired, and in film they generally have to work under pressured circumstances. The more time you can give them, the better. For most of what follows I am indebted to my son Paul Rabiger, who lives and works in Cologne, Germany, where he makes music for television and film. Like many involved in producing music these days, he works largely with synthesizers, using live instruments as and when the budget allows. Software favored by composers includes Steinberg Cubase and Emagic Logic Audio. Programs like these permit many tracks, integrate Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) with live recording, and support video in QuickTime format so the composer can build music to an accurate video version of the film.

COPYRIGHT

Never assume that recorded music you would like to use will be available when you get around to inquiring. The worst time to negotiate with composers, performers, publishers, and performing rights societies is when your film has come to depend on a particular recording. You are now in the weakest position, and lawyers with a nose for such things will capitalize on this. Commissioning original music obviates the difficulty of getting (and paying for) copyright clearance on music already recorded.

WHEN THE COMPOSER COMES ON BOARD

If the composer comes on board early, he or she will probably read the screenplay and see the first available version of the edited film. An experienced composer will probably avoid coming in with preconceived ideas and will inquire what the director wants the music to contribute. The composer can then mull over the characters, the settings, and overall content of a film, taking time to develop basic melodic themes and deciding within the budget what instrumental texture works best. Particular characters or situations often evoke their own musical treatment or leitmotif (recurring theme), and this is always best worked out with some time on hand, especially if research is necessary because music must reflect a particular era or ethnicity.

WHEN THERE's A GUIDE TRACK

Sometimes while editing, the editor may drop in sample music that nobody expects to keep but which helps assess the movie's potential. At the screening the composer may be confronted with a Beatles song or a stirring passage from Shostakovich's Leningrad Symphony. This certainly shows what a certain kind of music does for the scene and indicates a texture or tempo that editor and director think works, but it also raises a barrier because the composer must extract whatever the makers find valuable (say in rhythm, orchestration, texture, or mood) and then try to reach beyond the examples with his or her own musical solutions.

DEVELOPING A MUSIC CUE LIST

Once the content of the film is more or less locked down, it is screened in video form with composer, director, editor, and producer. The tape version has time-code burned into the lower part of the screen, which displays a cumulative timing for the whole film. The group will break the film down into acts and note where these occur on the film's timeline. They will discuss where music seems desirable and what kind seems most appropriate. Typical questions will center on how time is supposed to pass and whether music is meant to shore up a weak scene. The composer finds out (or suggests) where each music section starts and stops and aims to depart with a music cue list in hand and full notes as to function, with beginnings and endings defined as timecode. Start points may begin with visual clues (car door slams, car drives away) or dialogue clues (“If you think I'm happy about this, you've got another think coming.”).

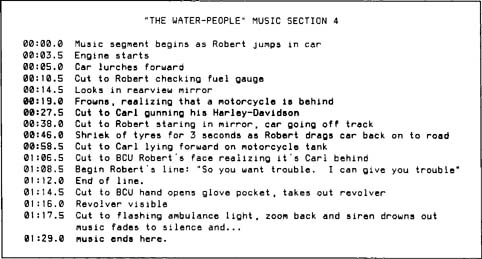

If the editor generates the music cues, sections should be logged in minutes and seconds down to the nearest half second. Figure 42-1 shows what a composer's cue sheet looks like. Like other addictive substances, music is easy to start but difficult to finish. You'll have no difficulty starting a music segment, but ending one so the audience does not feel deprived will take careful planning. A rule of thumb is to conclude or fade out music under cover of something more commanding. You might take music out during the first seconds of a noisy street scene or just before the dialogue in a new scene. The best study of practice is to view films that successfully integrate music with the kind of action you have in your film.

The computer-savvy composer then gets a tape copy to compose to. He or she will either first create a traditional score to be performed and recorded or will work with computers and MIDI-controlled synthesizers to make music sections directly. In the course of hands-on composing, music cues are occasionally

added, dropped, or renegotiated when initial ideas meet actuality. Poorly placed or unjustified music may be worse than no music at all.

Sometimes a courageous composer will work backward from a musical destination. In Joseph Losey's The Go-Between (1971) Michel Legrand's superb score starts in the main character's boyhood with a simple, though slightly ominous theme taken from Mozart. As the boy's trauma over conflicting loyalties unfolds and more of the older man's present-day inquiry intrudes, the theme is developed into a fuller and more tragic voice for its elderly subject—whose outward life, ironically enough, is utterly atrophied.

WHEN TO USE MUSIC, AND WHEN NOT

Though music is most commonly used as a transitional device, filler, or to set a mood, there are other ways to use it. Try never to use it to enhance what can already be seen on the screen. Better is to use it to suggest what cannot be seen, such as a character's expectations, interior mood, or feelings he withholds. The classic example is Bernard Herrmann's unforgettable all-violin score for Hitchcock's Pyscho (1960), with its jabbing violin screams as the pressure within Norman Bates becomes intolerable. Music, so natural an element to melodrama, is perhaps hardest to conceive for comedy.

Music is often used to foreshadow events and build tension, but it should never give the story away. Nor should it ever “picture point” the story by commenting too closely. Walt Disney was infamous for Mickey Mousing his films—an industry term for fitting scores like aural straitjackets around the minutia of action. The first of his true-life adventures, The Living Desert (1953), was full of extraordinary documentary footage but marred by scorpions made to square dance and music that supplied a different note, trill, or percussion roll for everything that dared move. Used like this, music becomes controlling and smothering.

A related mistake is to use too much music, burdening the film with a musical interpretation that disallows making your own emotional judgments. Hitchock's Suspicion (1941) and many a film of its vintage is marred this way. Far from heightening a film, the score flattens it by maintaining an exhausting aura of perpetual melodrama. The ubiquitous TV westerns of the 1950s and 1960s served up unending music punctuated by gunshots, horse whinnies, and snatches of snarling dialogue. Luckily, fashions change, and today less is considered more. A rhythm alone, without melody or harmony, can often supply the uncluttered accompaniment a sequence needs.

When its job is to set a mood, the music should do its work and then get out of the way to return and comment later. Sometimes a composer will point out during the screening just how effective, even loaded, a silence is at a particular point. The rhythms of action, camera movement, montage, and dialogue are themselves a kind of music, and you need not paint the lily.

Better than using music to illustrate (which merely duplicates the visual message) is to counterpoint the visible with music that provides an unexpected emotional shading. An indifferently acted and shot sequence may suddenly come to life because music gives it a subtext that boosts the forward movement of the story. In a story with fine shading, a good score can supply the sense of integrity or melancholy in one character and the interior impulse directing the actions of another. Music can also enhance not just the givens of a character, but it can indicate the interior development leading to an action and imply motives not otherwise visible. Music can supply needed phrasing to a scene or help create structural demarcations by bracketing transitions in scenes or between acts. Short stings or fragments of melody are good if they belong to a larger musical picture.

Given that an intelligent film is a weave of scenes whose longitudinal relationships can often stand strengthening, a composer may color-code his cues to group scenes, characters, situations, and the like longitudinally into musically related families. In a 40-minute film there may be 30 music cues, from a sting, or short punctuation, to a passage that is extended and more elaborate. He (or she, of course) may want to develop music for a main plot, but have musical identities for two subplots. Keeping these separate and not clashing during cross cutting can be problematic, so their relationship is important, particularly in key. Using a coding system keeps the composer aware of the logical connections and continuity the music must underpin.

Because there are many factors involved in producing an integrated score, it is important that music cues, once decided, should not be changed later without compelling reason.

KEYS, AND DIEGETIC AND NON-DIEGETIC MUSIC

An initial planning stage for the composer is deciding what progression of keys to use through the film, based on the emotional logic of the story itself. Especially when one kind of music takes over as a commentary upon another, the key of the latter must be related so the transition is not jarring. This is true for all adjacent music sections, not just original scoring. A film may contain popular songs the characters listen to in their car, and related scored music must be appropriate in key.

Any sound that is a part of the characters' world is called diegetic sound. Following it may be a very different kind of music, perhaps a score of massed cellos. Of course the characters do not hear or react to this, for it is part of the film's authorial commentary and is addressed to the audience. This is called non-diegetic sound.

CONFLICTS AND COMPOSING TO SYNC POINTS

An experienced musician composing for a recording session will write to very precise timings, paying attention to track features such as the tire screech and dialogue lines. The choice of instrumentation must not fight dialogue, nor can the arrangement be too busy at points where music might compete with dialogue or effects. Music can, however, take over the function of a diegetic sound track that otherwise would be too loaded. Musical punctuation, rather than a welter of naturalistic sound effects, saves time and labor and can produce something more impressionistic and effective. It's worth noting that an overloaded, over-detailed sound track takes energy on the part of the audience to interpret and is not well reproduced by the television speakers through which many people may hear your work.

If the composer is to work around dialogue and spot effects, he or she should have an advanced version of the sound track rather than the simple dialogue one used during editing. This is particularly true in any track that will be heard in a cinema setting. The sound system is likely to be powerful and sophisticated, and the film's track will come under greater artistic scrutiny.

When a written score is recorded to picture, it is marked with the cumulative timing so that as the music is recorded (normally to picture as a safeguard), the conductor can make a running check that the sync points line up. The composer might put a dramatic sting on the first appearance of the pursuing motorcycle at 27.5 seconds and on the appearance of the revolver at 01:16, for instance.

Low-budget film scores aren't usually live recordings but instead make use of MIDI computerized composing techniques. The composer builds the music to a QuickTime scratch version of the film, digitized from a cassette, so music fitting is done at the source.

HOW LONG DOES IT TAKE?

An experienced composer likes to take more than 6 weeks to compose about 15 minutes of music for a 90-minute feature film, but she may have to do it in 3, with a flurry of music copyist work at the end, to be ready for the recording session.

THE LIVE MUSIC SESSION

The editor makes the preparations to record music and attends the recording session because only the editor can say whether a particular shot can be lengthened or shortened to accommodate the slight timing inaccuracies that always appear during recording. Adjusting the film is easier and more economical than paying musicians to pursue perfect musical synchronicity.

FITTING MUSIC

After the recording session, the editor fits each music section and makes the necessary shot adjustments. If the music is appropriate, the film takes a quantum leap forward in effectiveness. Some editors specialize in cutting and fitting music. Their expertise is important to a musical, in which much of the film is shot to playback on the set.

THE MIX

The composer will want to be present at all mix sessions affecting the functionality of the music he or she has composed. When music has been composed on MIDI, it is only a matter of a small delay to return to the musical elements and produce a new version with changes incorporated.