CHAPTER 7

SCREENWRITING CONCEPTS

WHEN YOU DIRECT FROM YOUR OWN WRITING

As a beginner, you will need to write and direct your own short films. Though your first films will be simple, read the chapters on writing, form, and structure. Sometimes people are impatient and look down on exercises and projects as “not real films,” but every piece for the screen, no matter how short, faces you with options in point of view, genre, plot, and style, all of which are treated in the coming chapters. There is a huge amount to learn from making short films, but be prepared to profit as much from negative experiences as from positive ones. Later I will argue for collaboration with a screenwriter, but for now, let's assume you are a writer-director.

For any story to work well on the screen, no matter how short, allow much time and a number of drafts in which to complete the writing process, and seek out honest criticism at key stages. Doing so is like exposing your film to audience reactions in advance. Film is an audience medium, yet beginning directors tend to hide from exposure as long as possible. One way to get criticism is to pitch your work, which means you describe its essentials orally in brief and exciting form to another person. Today this has become a vital skill for a director, producer, or screenwriter to possess. See the beginning of Chapter 8 for more details.

DECIDING ON SUBJECTS

As you make exercise films to learn the basics of film technique and grammar, take care to choose subjects you care about. You will have to live with your choice and its ramifications for some time. Once you start shooting, you should complete the film, no matter what. If this commitment sounds scary, it can be explored with the option of retreat all through the writing and rewriting stages. Writing and rewriting as you move among the three dimensions of screenplay, step outline, and concept (explained in detail later) will allow you to inhabit a text, something virtually impossible from one or two detached readings. As always, when you translate from one mode of representation to another, you will discover a range of aspects hidden from the more casual reader, no matter how expert he or she may be.

Whether your film is to be comedy, tragedy, horror, fantasy, or a piece for children, it must embody some issue with which you identify. Everyone bears scars from living, and everyone with any self-knowledge has issues within, awaiting exploration. Your work will best sustain you when connected to something that moves you to strong feelings. This might be racial or class alienation, a reputation for clumsiness, fear of the dark (horror films!), rejection, an obsession, a period of intense happiness, or a brief affair you had with someone very beautiful. It might be a stigma such as illegitimacy, being foreign, or being unjustly favored—I repeat, anything that has moved you to strong feelings. Start a list. You will probably be surprised at two things: how many subjects you have to draw on and the themes that emerge when you look for common denominators.

Directing films demands both creation and contemplation—an outward doing and a parallel inner process of search and growth. This is the foundation of the artistic process. Your validity as a storyteller begins with the scars of experience rather than from ideas or ambitions that lack the bedrock of experience. We have all passed through war zones, so work in any corner of existence about which you know something and want to learn more. Avoid debating problems or demonstrating solutions. The object is not to produce a film that preaches or confesses but one that deals—in some suitably displaced way—with something you care deeply about. To feel satisfying to an audience, your story should show evidence in its main character of some change or growth, however minimal or even negative this may be.

START MAKING WORKING PARTNERSHIPS

After a year or two of production, most film students have a better idea of their interests and limitations and also realize they will need to work professionally in one of the allied crafts before anyone considers them mature enough to direct. You are helped in this by the virtual impossibility of finding directing work unless you emerge with a sensational piece of student work, as Robert Rodriguez did at the Sundance Film Festival with El Mariachi (1993). If you are committed to directing professionally, start looking now for your natural collaborators in writing, cinematography, and editing.

WHY READING A SCRIPT IS DIFFICULT

Whether you want to raise funds or just put your intentions before a crew and cast, communicating the nature of your film depends on the script. It seems simple—you just hand someone a script, don't you? But this may accomplish nothing useful; scripts are very demanding to read and a well-written one is purposely minimal. Because actors, director, camera crew, and even the weather all make unforeseeable contributions, the astute scriptwriter leaves a great deal unspecified. A script should consist of dialogue, sparse or nonexistent stage directions, and equally brief remarks on character, locations, and behavior. Until the shooting stage there will be no directions for camerawork or editing. The reader must supply from imagination what is missing, something that key crew members such as the director, technicians, and actors, do as part of their creative contribution to the project.

A screenplay is a verbal blueprint designed to seed a nonliterary, organic, and experiential process. Rarely if ever does it give more than a sketchy impression of what the film will really be like. Nor does it give many overt clues to the thematic intentions behind the writing. These must be inferred by the reader, again at considerable effort. The lay reader, expecting the detailed evocations of a short story or novel, feels that inordinate mental effort and experience is demanded to decompress the writing. More arduous than reading poetry and much less rewarding, reading scripts is not pleasurable. Inside the film industry and out, most people resist reading any more scripts than necessary. Most production companies, receiving several hundred a week, throw the unsolicited ones away or give them no more than a cursory glance, perhaps scanning every 10th page. Because the likelihood of finding anything usable is so small among the 50,000 or so scripts copyrighted annually, professionals will usually only look at work forwarded by a reputable agent.

To earn money by screenwriting, you must first write well enough to win the respect of a good agent. If you are a director looking for a script, expect a lot of hard and discouraging reading. In the film industry, first-rate scripts are extremely rare and their qualities immediately apparent. There is a terrible shortage of distinguished work. If you are in film school, start talent scouting.

STANDARD SCRIPT FORMS

The industry standard for layouts is simple and effective and has evolved as the ultimate in convenience. Do not invent your own.

SCREENPLAY FORMAT

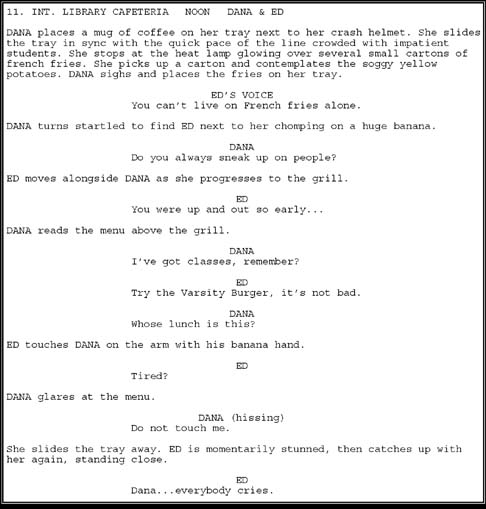

The sample page in Figure 7-1 illustrates the following rules for screenplay form:

Typeface: Screenplays always use the old-fashioned typewriter font called 12-point Courier. The industry has never moved away from this because one page in this format runs approximately a minute onscreen.

Scene heading: Each scene begins with a flush-left, capitalized scene heading that lists:

- Number of the scene

- Interior or exterior

- Location

- Time of day or night

- Main characters involved

Body copy: This material, which includes action description, mood setting, and stage directions, is double-spaced away from scene headings and dialogue and runs the width of the page.

Character names: Outside the dialogue these should appear in all capitals.

Dialogue sections:

- Should be headed by the speaker's name, centered and in all capitals

- Should be centered within extra margins

- Should be preceded and followed by a double space

- Are accompanied, when strictly necessary, by a stage direction inside brackets

Shot transitions: Terms like Cut to or Dissolve to are placed either flush left or flush right and are only included when unavoidable if the script is to make sense.

Figure 7-1 is a page in pure screenplay form. There are no camera or editing directions. Industry practices vary; some commercial scripts are hybrid creatures trying to dramatize their contents by moving closer to a shooting script. This may help to sell a particular script in a particular quarter, but in most places it has no practical value. Do what is normal from the beginning.

A TRAP FOR THE UNWARY

The screenwriter's most treacherous friend is the screenplay format itself, for its appearance and proportions suggest that films are built theatrically around dialogue. While this may be wretchedly true for soap opera, it is quite wrong for good screen drama, which is primarily behavioral. Actors and directors can also be lulled into assuming the primacy of the spoken over the behavioral. I do not mean to devalue the screenplay as the genesis of successful screen drama. Nobody has yet demonstrated that you can effectively coordinate actors and crew without a central structure, but this structure must be cinematic, not literary or theatrical. In fact, there are ways to reach it apart from the traditional one of writing, but that we'll explore later.

SPLIT-PAGE OR TV SCREENPLAY FORMAT

The split-page format (see Figure 5-2) is frequently used in multi-camera television studio shooting when a complex drama must be enacted in real time. For this reason the format is sometimes called a television or TV format script. In multi-camera television, all production elements have to be pre-envisioned and present because there is no postproduction. In cinema-style shooting, in which each shot is created discretely and the final version composed meticulously afterward in the cutting room, this density of detail is usually irrelevant.

Split-page format, however, is the best layout for logging and analyzing a finished movie. Unlike the screenplay, it allows clear representation of the counterpoint among images and among images and various sound elements. Notice that the left-hand picture column contains only what you would see and the right-hand sound column contains only what you would hear. Do not transpose them or the point of having a standard is lost.

Chapter 5, “Seeing With a Moviemaker's Eye,” strongly recommended that you make a split-page transcript of a few sequences from your favorite contemporary movies. If you did it, you discovered how dense film language is. The exercise also demonstrates how effectively the split-page format can toggle the reader's attention between dialogue and action. If you like alternative cinema, which often uses dialogue, music, and effects while intercutting different levels of footage (past, present, archive, graphics), you may find writing in screenplay format difficult or even paralyzing. Try using the split-page format in the planning stage, and convert it to screenplay format later if you need to.

SCRIPT FORM CONFUSIONS

Publishers have caused confusion by making no distinction between the original screenplay and continuity scripts or reader's scripts. Both the latter are transcriptions of the finished product and not the all-important blueprint that initiated it. The glossary in this text explains the differences. If you study scripts, make sure you know what you are reading; otherwise, you may form the appalling idea that films are written and made by omniscient beings. To compare a film with its original screenplay is to contemplate the multiplicity of changes and modifications that took place after the blueprint. Whereas cars are first designed, then manufactured, films are redesigned and evolved throughout the process, from the first idea all the way to final mixing and color balancing the print.

PREPARING TO INTERPRET A TEXT

After your first reading of a screenplay, examine the imprint it left on you:

- What did it make you feel?

- Whom did you care about?

- Whom did you find interesting?

- What does the piece seem to be dealing with under the surface events?

Note these impressions and read the screenplay once or twice again, looking for hard evidence to go with your first impressions. Next ask yourself the following:

- What is the screenplay trying to accomplish?

- What special means is it using to accomplish its intentions?

Again, note your answers. Now leaf through the screenplay and make a flow chart of scenes, giving each a brief, functional description (Example: Scene 15: Ricky again sees Angelo's car; realizes he's being watched). From this list of scenes and their dramatic intentions, you are more likely to pinpoint the screenplay's dramatic logic, something difficult to abstract any other way. If you can't find it, this is a bad sign. If you can see some logic that the screenwriter seems unaware of, this is quite usual and is the reason directors and writers work together on rewrites of the script.

Having established some initial ideas about a screenplay's structure and development, we can now look at significant details.

GOOD SCREENPLAYS ARE NOT OVERWRITTEN

Because a screenplay is a blueprint and not a literary narrative, it is important to ruthlessly exclude embellishment. A good screenplay:

- Includes no author's thoughts, instructions, or comments

- Is reticent with qualifying comments and adjectives (over-describing kills what the reader imagines)

- Leaves most behavior to the reader's imagination and instead describes its effect (for example, “he looks nervous” instead of “he nervously runs a fore-finger round the inside of his collar and then flicks dust off his dark serge pants”)

- Under-instructs actors unless a line or action would be unintelligible without guidance

- Contains no camera or editing instructions

- Isn't written on the nose (over-explicitly, telling everything instead of leaving the viewer with interpretive work to do)

- Uses brief, evocative language whenever the body copy wants the reader to visualize

The experienced screenwriter is an architect who designs the shell of a building and knows that others will choose the walls, interiors, colors, and furnishings. A good reason to avoid over-instructing your readers is that you prevent them from filling deliberate ambiguities with positive assumptions. Inexperienced screenwriters tend to be control freaks who, in architectural simile, design the doorknobs, lay carpet, hang pictures, and end up making the building uninhabitable by anyone but themselves.

The writer-director might seem to be a special case. Because he or she should know exactly what is to be shot, where it is to be shot, and how, why not write very specifically? This overlooks the realities of filming. Without unlimited time and money, nothing much works out as you envision, so it's foolish to specify anything you may not be able to deliver.

Overwriting is not just impractical, it's hazardous. Any highly detailed description conditions your readers (money sources, actors, crew) to anticipate particular, hard-edged results. The director of such a script is locked into trying to fulfill a vision that disallows variables, even those that would contribute positively.

LEAVE THINGS OPEN

How a script is written sends messages to actors. An open script invites the cast to offer their own input while the over-specific, closed one expects actors to conform to the actions and mannerisms minutely specified in the text, however alien they may be. Challenging actors does not mean trying to minutely control them; on the contrary, it means getting from each a different and distinct personal identity. The good screenplay assists this by leaving the director and players to work out how things will be said and done. This encourages the creativity of the cast and catalyzes an active process between cast member and their director.

WRITE BEHAVIOR INSTEAD OF DIALOGUE

The first cowboy films made a strong impact because the American cinema recognized the power of behavioral melodrama. The good screenplay is still predominantly concerned with behavior, action, and reaction. It avoids static scenes in which people verbalize what they think and feel, as in soap opera.

PERSONAL EXPERIENCE NEEDS TO BE ENACTED, NOT SPOKEN

Everyone is moved by aspects of their own life, and every writer includes auto-biography in their writing. But a writer must distinguish between the intensity of life experienced subjectively and that which remains powerful or exciting when seen only externally in the cinema. In a moving personal experience, you are actively involved and acted upon, feeling powerful pressures subjectively and within. In screen drama, the characters' inner thoughts and emotions can only communicate to outsiders as they do in life itself—through outwardly visible behavior. Drama is about doing, so what matters most on the screen is what actions people take. Every screen character who is at all compelling is trying to get or do something. All the time. Just as you are in your life, year to year, day to day, minute to minute. The trouble is, we are very aware when we feel something but are blindly unaware of nearly everything we do or did in pursuit of our objectives.

RECOGNIZING CINEMATIC QUALITIES

A simple but deadly test of a script's potential is to imagine shutting off the sound and assessing how much the audience would understand (and therefore care) about what remains. Submitting each sequence to this test reveals how much of it is conceived as behavior and how much as dialogue. This is not to deny that we talk to each other or even that many transactions of lifelong importance take place through conversation. But being one of the protagonists is one thing, and looking at someone on the screen is another. An onlooker is convinced by characters' actions more than their words, and it is through actions that we gain reliable insight into another person's inner life. Making effective drama means making the inner struggles of characters visible through their outward actions. Dialogue should therefore be used only when necessary, not as a substitute for action. Dialogue should itself be action, that is, it should be people acting upon each other, never people narrating their thoughts and feelings to each other.

CHARACTERS TRYING TO DO OR GET

We judge a screen character as we do someone in life, by first assessing all the visible clues—appearance, body language, clothes, and how they wear them. We look into the person's face, belongings, and surroundings to form initial impressions.

Watching how someone handles obstruction, we are primed to interpret available details of their background, such as their formative pressures, assumptions, and associations. We try to decide which among these the person chose and which were thrust upon them. How the person reacts—in particular to the unexpected or threatening—tells us much, as do the attitudes of their friends and intimates. These interactions also help to establish the goals, temperaments, and histories of the other characters.

A character's path is not determined by personal history alone; there is nature as well as nurture. Temperament, an active component in anyone's make-up, exerts its own influences in the face of conditioning at the hands of family and society. “Character,” said Novalis, “is destiny.” The astute writer never forgets this. Most of all, we make character judgments from the moral quality of a person's deeds. Each unexpected predicament a person faces is really a test of his or her moral strength, and what he or she does modifies or even subverts what hitherto appeared true. It may change what that person “is”—even to himself or herself.

To produce this evidence, dramatists strew the paths of their characters with obstacles. Your job as a dramatist is to dream up credible acts, situations, and environments that will propel your protagonist forward as he or she tries to get or do what lies on the agenda. Building lifelike contradictions into a character helps the audience to see human complexity—quite different from the illustrative portrayal that reeks of “message.” Contradictions in a character's actions and beliefs are necessary if the person is to have inner conflicts. In heroic drama, conflicts are drawn as good characters against evil ones. But characters in contemporary realism need to be complex and have inner conflicts if they are to seem whole and have any magnitude.

STATIC CHARACTER DEFINITION—ONLY A BEGINNING

When deciding a screenplay's potential, assess the characters by more than their givens (such as age, sex, appearance, situation, and eccentricities). These are only a static summation, something like a photograph that typifies them but makes their development seem already closed and complete. Watching this kind of character in a film is like seeing a photomontage in which each person is fixed in a typical role and attitude. This constriction is unavoidable in the TV commercial, which must be brief and propagandistic. There each character is set by one or two dominant characteristics so that everyone is typical: a typical mother, a typical washing machine repairman, a typical holiday couple on a typical romantic beach. Homes, streets, meals, and happy families are all typified—which is to say, stereotyped.

When drama is conceived in a closed and illustrative form, players struggle in vain to breathe life into their characters, for everything their characters do and everything that befalls them falls back into that dominant and static conception. This prescriptive tendency denies and paralyzes the willpower, tensions, and adjustments present in even the most quiescent human being, and it prohibits the growth and change essential to being alive and inherent in real drama.

DYNAMIC CHARACTER DEFINITION—CHARACTER IN ACTION

What we need is a dynamic conception of character, one focusing on flux and mobilizing the potential for development instead of paralyzing it. The secret, so vital to writers and actors alike, is to go beyond what a character is and formulate what that character is trying to get or do. This is dynamic and interactive and deals with what the person is trying to accomplish and perhaps become.

In good drama you can see and feel each main character's will pitted against the surrounding obstacles. It's like studying an ant moving through gravel. We can see where the character is going and what he faces every step of the way, and we can become deeply involved in how he solves all the obstructions. This won't be true of writing in which the writer does not grasp how central volition is to characters and to drama itself. To uncover this kind of inner structure (or its absence) in drama, pick an active moment in a scene and apply the following questions:

- What is this character moving away from?

- What is this character moving toward?

- What is this character trying to get or do, long term?

- What is this character trying to get or do, this moment?

- What is this character facing as a new situation?

- What is this character obstructed by?

- What does the character want next?

- How is this character trying to overcome the obstacle?

- How is this character adapting to the obstacle? (Successfully? Unsuccess-fully?)

- How is this character faced with a new situation after trying to adapt?

- How is this character changed in terms of goals by this experience?

Applying these what and how questions probes a character's development, moment by moment, and uncovers the character's immediate goals, as well as those that are longer term. Soon you can see how thoroughly a piece of dramatic writing has been thought through, and what weak areas need analyzing in the next step, which is identifying solutions and toughening a script's internal structure.

CONFLICT, GROWTH, AND CHANGE

Every rule has its exceptions, but dramatists generally agree that all stories need at least one character who shows some degree of growth and change or the story will seem hopeless. This learning is called a character's development. In accomplished writing, even minor characters pursue an agenda; that is, they struggle for something, face inner conflict or outer opposition, and they may even learn something, too. A short film, like a short story, needs only one character who shows a degree, however small, of development. A feature film, being longer, has a more complex architecture.

The screenwriter's job is to supply clues to evolving tensions in the characters. The 10 how and what questions listed previously are designed to detect evidence of this vital conflict and movement. When the answers for what each character says and does are consistent, you sense that you are completing a join-the-dots puzzle. As the evidence mounts, the character becomes someone struggling for consistent ends and who communicates the touching qualities of a living human being.

No story of any genre will have the power to move us unless its main or point-of-view character has to struggle, grow in awareness, and change. Particularly in a short film, this development may be minimal and symbolic, but its existence is the cardinal sign of a strong story. That a character learns something and grows a little seems to answer our perennial craving for hope and counters the many otherwise discouraging elements of contemporary life.

To breathe life into each character in a drama, the company and its director must create the whole from the clues embedded in the characters' words and actions. Most importantly, this must be conceived in the actors' own coin and cannot be dictated by the writer or director, who are midwives to truth, not its final creators.

PLANNING ACTION

At its most eloquent, the screen is a behavioral medium—one that shows rather than tells. Look at the list of sequences in a script and rate how readily each could be understood without sound. In some sequences the film's narrative is evident through action. In others the issues are handled verbally and could use translating into action. For example, in a breakfast scene, while a father gives his young son a sermon about homework, you could work out business in which the boy tries to rearrange and balance the cutlery and cereal boxes, while the father, trying to get his full attention, attempts to stop him. Though we don't see the precise subject in dispute, the conflict between them has been externalized as action.

Now whether this is best kept as work with the actors or whether it calls for script revision depends on your judgment. Will solving a particular problem encourage or inhibit your actors' creativity? Too little margin for imagination is stultifying; but too open, static, and empty a text may pose overwhelming problems of interpretation.

Usually a dialogue scene is always improved when reconceived as action. Say the boy comes home to find his father waiting with the schoolbooks set out. Reluctantly he sees what is at issue and silently takes the books into his room. Later his father looks in and finds his son sprawling in headphones listening to music. At breakfast the boy avoids his father's eye, but, unasked, goes to the doorstep to get his father the paper with guilt and remorse in his action. Now the need for confrontation and interaction has been turned entirely into a series of situations and actions, and it avoids the theatrical set-piece conversation.

However you solve the problem, try to substitute action for every issue handled verbally. It may be minimal facial action, it may be movement and activities of a revealing metaphorical nature, or it may be movement that the actor thinks will heighten his character's interior tension by concealing rather than revealing his true feelings.

Action and conflict are inherently interesting because action is the manifestation of will. Actions become even more interesting when they conflict with what a character says. Such contradiction can reveal both inner and outer dimensions, the conscious and the unconscious, the public and the private.

The antithesis of this principle is the script in which a tide of descriptive verbiage drowns whatever might be alive and at issue.

ROSE

Uncle, I thought I'd just look in and see how you are. It's so miserable to be bedridden. You're Dad's only brother and I want to look after you, if only for his sake.

UNCLE

You're such a good girl. I always feel better when you look in. I thought I heard your footsteps, but I wasn't sure it was you. It must be cold outside—you're wearing your heavy coat.

You are looking better, but I see you still aren't finishing your meals. It makes me sad to see you leave an apple as good as this when you normally like them so much.

UNCLE

I know dear, and it makes me feel almost guilty. But I'm just not myself.

I wrote this to show the worst abominations. Notice the redundancies, how the writing keeps the characters static, how there is no behavior to signify feelings, and no private thought separate or different from the public utterances. Neither character signifies any of the feelings or hidden agenda that gives family interaction its rich undercurrents. Even between people like these, who like each other, there are always tensions and conflicts. But this writing grips the audience in avice of literalness, lacking even unspoken understandings for the observer to infer. Most damning, nothing would be missed by listening with eyes closed. It is the essence of bad soap opera.

By reconceiving this scene to include behavior, action, and interaction, you could prune the dialogue by 80% and end up with something animated by a lot more tensions. If the scene is meant to reveal that the old man is brother to Rose's father, there must be a more natural way for this to emerge. At the moment, editorial information issues from her mouth like ticker tape. Perhaps we could make her stop in her tracks to stare at him. When he looks questioningly back, she answers, “It must be the light. Sometimes you look so much like Dad.” His reaction—whether of amusement, irritation, or nostalgia—then gives clues about the relationship between the brothers.

DIALOGUE

In most movies, people speak to each other a lot, and this raises the question of how to write good dialogue and how to write different characters because most writers create characters who all speak with the same voice.

Cinema dialogue sets out to be vernacular speech. Whether the character is a young hood, an immigrant waitress, or an academic philosopher, each will speak in their own street slang, broken English, or strings of qualified, jargon-laden abstractions. What type of thought, what type of speech, will each character use?

Dialogue in movies is different from dialogue in life. In the cinema it must sound true to life yet cannot include life's prolixity and repetitiousness. Cinema dialogue is highly succinct though just as informal and authentically “incorrect.” Dialogue must always steer clear of what the camera reveals and avoid imposing redundant information (“You're wearing your heavy coat,” as in the previous example).

Because each character needs his or her own dialogue characteristics, writing good dialogue is an art in itself. Vocabulary, syntax, and verbal rhythms for each character have to be special and unlike another's. Getting this right takes dedicated observation or an extraordinary ear. Eavesdropping with a cassette recorder will give you superb models, and if you transcribe everything, complete with ums, ers, laughs, grunts, and pauses, you will see that normal conversation is not normal at all. People converse elliptically, often at cross-purposes, and not in the tidy ping-pong exchanges of stereotypical drama. In real life, little is denoted and much connoted. Silences are often the real “action” during which extraordinary currents are flowing between the speakers. To study how people really communicate is a writer's research.

You will learn much by taking some eavesdropped interchanges and editing them. You are doing on paper what an editor does when editing a radio documentary, that is, editing out what is redundant yet retaining the individual's sense and idiosyncrasies. Any documentary editor will tell you how much stronger characters become when reduced in this way to their essence. This is the secret of a master of dialogue like Harold Pinter, or any good mimic or comedian. They truly listen, and in listening, search out the keys to the person's behavior and thinking. Comedians make us laugh by revealing the characteristics of a type of person such as the office bore, the mother convinced that her child is a genius, the organic food nut, and so on.

The best dialogue is really verbal action because in each line the speaker is aiming to get something. It is pressure applied even as it seeks to deflect pressure being experienced. It is active and structurally indispensable to the scene, never a verbal arabesque or editorial explanation of what is visible. Least of all is it verbal padding.

The best way to assess dialogue is to speak lines aloud and listen to their sound. Afterwards apply these questions:

- Is every word in the character's own language?

- What is this character trying to do or get with these words?

- Does the dialogue carry a compelling subtext (that is, a deeper underlying connotation)?

- Is what it hides interesting?

- Does it make the listener speculate or respond emotionally?

- Is there a better balance of words or sounds?

- Can it be briefer by even a syllable?

PLOT

Plot is a complex issue and is closely allied to a film's structure. It is handled at length in Chapter 14, “Structure, Plot, and Time,” but here is a quick introduction. The plot of a drama is the logic and energy driving the story forward, and its job is to keep the audience's interest high. A screenplay's plot only becomes fully visible when you make an outline. Every step the characters take must be logical and inevitable, for anything that is unsupported, arbitrary, or coincidental will weaken the chain of logic that keeps them in seemingly inevitable movement.

In a plot-driven story, sheer movement of events usually compensates for lack of depth or complexity in the characters. By giving attention to the plot in a character-driven movie, the audience has something other than characters and their issues to find interesting, and you can often appreciably strengthen the whole.

PLOT POINTS

A plot point is a moment in which a story, moving in one direction, suddenly goes off on an unpredictable tangent. If, for example, in a story about a happy young couple going on their first holiday together, the man suddenly freezes on the steps of the airplane and will go no farther, we have an unpredictable turn of events. It turns out that he has concealed his claustrophobia, and they must somehow go abroad by sea instead. On the steps of the boat, the young woman clings to the rail on the quay: She has concealed her agoraphobia. Another plot point. What will they do next?

Plot points are not only recommended in Syd Field's work on screenwriting— their placing is recommended, too. The point is that tangents and the unexpected are useful as a means of shaking things up, of periodically demolishing the predictability that a story adopts. They help to keep dramatic tension high. Keep ‘em guessing.

METAPHORS AND SYMBOLS

What makes the cinema so powerful is that the inner experiences of the main characters can often be expressed through artfully chosen settings, objects, and moods. These function metaphorically or symbolically as keys to deeper issues. I suspect this is the magic that draws people to camerawork and is where cinematography must serve more profound purposes than the training people are able to get usually includes. The parched, bleached settings in Wim Wenders' Paris,Texas (1984) are emblematic of the emotional aridity of a man compulsively searching for his lost wife and child. In John Boorman's Hope and Glory (1987), the beleaguered suburb and the lush riverside haven dramatize the two inimical halves of the boy's wartime England. They also betoken his split loyalties to the different worlds and social classes of his parents. The film has many symbolic events and moments, one being as the boy disinters a toy box from the ruins of the family's bombed house. Inside are lead soldiers charred and melted in eerie mimicry of the Holocaust. Though the image is only on the screen a few seconds, everyone remembers it. For it perfectly represents war and loss not only for the boy, the son of a soldier, but also for all those immolated in warfare—particularly the victims of the Nazi Holocaust. It also suggests the poignant irreversibility of change itself and the loss of childhood.

Symbols and symbolic action have to be artfully chosen because advertising has equipped audiences to decisively reject the manipulative symbol or over-earnest metaphor even before it has fully taken shape. Most importantly, metaphoric settings, acts, and objects need to be organic, that is, drawn from the world in which the characters live. They cannot be imposed from outside or they become contrived and editorial.

One of the most breathtaking integrations of metaphor into screen drama is in Jane Campion's The Piano (1993), which sweeps the viewer up in its earliest scenes. That power is visible in the briefest summary: Ada, a young immigrant Scot who won't or can't speak, arrives with her illegitimate daughter and her piano on the wild New Zealand seashore of the 19th century. She is there to marry a man she neither knows nor loves and who refuses to bring home her piano. Instead it goes to another man's home. Inevitably, it is he and not her husband who listens to her music, and it is to him that she gives her body and soul.

We are in a realm where nature is truly savage, love is denied by decorum, subtlety is beyond the reach of language, and the soul reaches out by way of music and suppressed eroticism. Who could ask for a more potent canvas?

FOUNDATIONS: STEP OUTLINE, TREATMENT, AND PREMISE

Though a screenplay shows situations and the quality of the dialogue writing, it offers little about point of view, that is, about the subjective attitudes that must be conveyed through acting, camerawork, and editing. Still less does it explain the subtexts, ideas, and authorial vantage point we are supposed to infer and that presumably motivated the writing in the first place.

If you are starting production work from a completed script, you will need to generate some short-form writing yourself to help you develop dramatic over-sight of the piece in hand.

STEP OUTLINE

Writing methods vary considerably, but at some point many directors or writers make a step outline, which is a summary that:

- Is told in short-story, third-person, present-tense form

- Includes only what the audience will see and hear from the screen

- Allots one numbered paragraph to each sequence

- Summarizes conversations, never gives them verbatim

Making a step outline invariably leads to all kinds of fresh ideas and evolution-ary changes. A step outline should be periodically rewritten to reflect the changes between drafts of the screenplay.

The step outline should read as a stream-of-consciousness summation that never digresses into production details or the author's comments. Remember to put down only what the audience will see and hear. Write no dialogue, just stick to essentials by summarizing in a few words each scene's setting, action, and an overview of any conversation's subject and development.

Step Outline for THE OARSMAN

- At night, between the high walls of an Amsterdam canal, a murky figure in black tails and top hat rows an ornate coffin in a strange, high boat. In a shaft of light we see that MORRIE is a man in his late 30s whose expression is set, serene, distant.

- Looking down on the city at night, we see a panoramic view over black canals glittering with lights and reflections, bridges busy with pedestrian and bike traffic, and streetcars snaking among crooked, leaning, 17th-century buildings. As the view comes to rest on a street, we hear a noisy bar atmosphere where, in the foreground, a Canadian woman and a Dutch man are arguing fiercely.

- Inside the fairly rough bar with its wooden tables, wooden floor strewn with peanut shells, and wooden bar with a line of old china beer spouts, is JASMINE, a tough but attractive young Canadian in her late 20s. She is trying to leave the bar during a bitter argument with her tattooed and drugged-looking Dutch boyfriend MARCO. She says she's had enough.

Each numbered sequence represents a step in the story's progression, and the whole step outline becomes a bird's eye view of the balance and progression of the material, whether the screenplay is a work in progress or a final draft. Actually, the only final draft is the finished film. Everything else is in evolution.

TREATMENT

A treatment is a narrative version written in present-tense, short-story form. It, too, concentrates on rendering what the audience will see and hear and summarizes dialogue exchanges. It is briefer than a screenplay to read and easier to assimilate. Confusingly, the term treatment is also used for the puff piece a writer may generate to get a script considered by a particular production company. Geared toward establishing the commercial potential of the film, some treatments function like a trailer that advertises a coming attraction, and they often present the screenplay idiosyncratically for whomever is being targeted.

PREMISE

Neither screenplay, treatment, nor step outline articulates the ideas underpinning the film's dramatic structure and development. This, directly defined as the premise, is sometimes called the concept. It is a sentence or two expressing the dramatic idea behind the scene or behind the whole movie. The premise behind Robert Altman's Gosford Park (2001) might be “When a leader or magnate uses power corruptly he will eventually be toppled, no matter how far-reaching his power, and no matter how cynically he buys off his supporters.”

Like everything else in this organic process, the premise often mutates as you journey ever deeper into the material. After you and your writer have been working together, make a point of revisiting the premise. Seeking it will always yield the paradigm of your latest labors and let you know if and how your work is thematically focused. This is one of the most magical aspects of working on narratives.