CHAPTER 10

STORY DEVELOPMENT STRATEGIES

While creating a story, the writer alternates between generating story materials and editing them in pursuit of character development and plot unity. In the generating mode, give free rein to inspiration and write organically and disconnectedly as ideas, scenes, characters, and situations appear in your imagination. This is letting the work help to create itself.

Then, once the blitz of a generating phase is over, you begin editing; that is, you review and analyze what you have produced to develop it. Like a manic potter who produces flawed and surplus goods among the useful, there comes a time when production must be halted to allow someone to organize, classify, tidy up, and throw out the junk. Here you need methods by which to re-impose order. Whether potter or writer, nobody creates in a vacuum. Virtually all characters and situations, no matter how up-to-date, are variations of archetypal patterns. To deny this or hide from it is not preserving your originality so much as refusing the help of parentage that even great artists welcome. Later in the chapter we will look at how to find and use archetypes.

If you are assessing a completed script or working on your own writing, you will need to get a dramatic oversight of the piece. This is equally true whether you have five pages or 150. You will need to apply the analytical tools of the step outline, premise, concept, and treatment.

The step outline is like the framework of headings I used to begin writing this book. Any extended writing is a slow, circular activity like fumbling your way through a dense forest. Even after starting from a clear plan I regularly lost sight of the overview of what I was doing, and I had to create content lists to see exactly where I had been and where I still needed to go. When you first picked up this book, you probably looked in the list of chapters, tables of contents, and index to see whether it contained what you wanted. These summations functioned for you and me both. Writing a story is a lot more complex than writing a manual, and it needs periodic reorganizing and overview all the more.

EXPANDING AND COLLAPSING THE SCREENPLAY

The step outline is an excellent starting point for writing a screenplay, but it is an equally useful tool for traveling in the opposite direction, that is, for simplifying the essentials of a completed screenplay draft. Working in screenplay format means the basic structure often becomes obscured, particularly from its own progenitor. When a screenplay presents problems (and which one doesn't?) it will help to make a step outline that reveals the plot and inherent structure.

Reducing the screenplay to step outline and then further reducing the step outline to a ruling premise are vital steps in testing a story's foundations. (See Chapter 7, “Script Development Essentials.”)

STORY ARCHETYPES

Major work has been done in the last few decades surveying story archetypes. While archetypes are especially helpful to fiction writers in the editing and structuring phase of their work, you will almost certainly find them inhibiting as a starting point. Their completeness can be paralyzing. That's why I've waited to present this material until a section dealing with story-editing tools. When you write initial drafts, put formulae out of your mind and follow your inclinations. Create first, no matter how poorly; then shape and edit later when the world you have set in motion is firmly established. Myths and archetypes become most helpful for a story with difficulties or when you become stuck.

In the Notes and Queries section of the international newspaper Guardian Weekly, a reader asked if it was true that there are only seven basic stories in fiction. An obliging reader responded with eight:

- Cinderella—virtue eventually recognized

- Achilles—the fatal flaw

- Faust—the debt that catches up with the debtor

- Tristan—the sexual triangle

- Circe—the spider and the fly

- Romeo and Juliet—star-crossed lovers who either find or lose each other

- Orpheus—the gift that is lost and searched for

- The Hero who cannot be kept down

To these other readers added:

9. David and Goliath—the individual against the state, community, system, etc.

10. The Wandering Jew—the persecuted traveler who can never go home

Another reader pointed out that it is fictional themes, not stories, that are said to be limited to seven. They are:

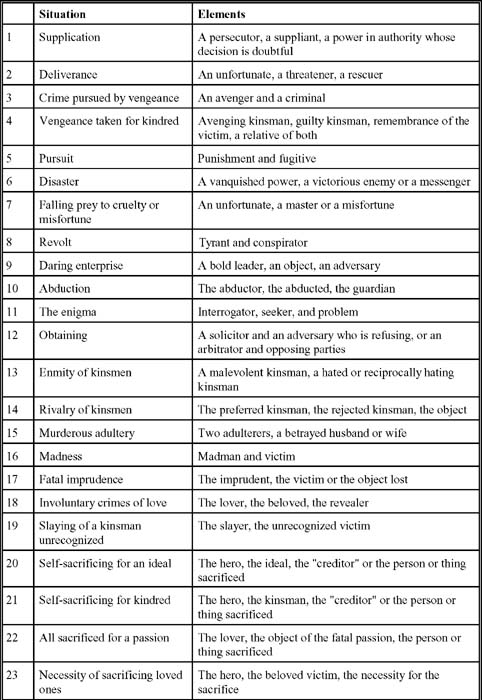

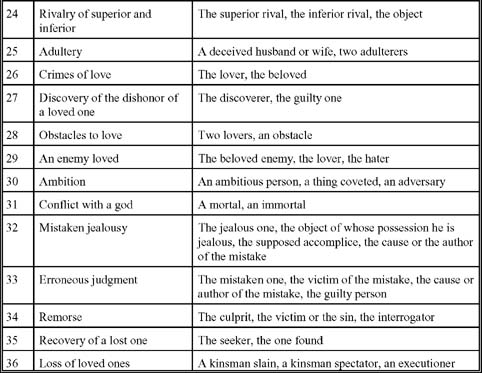

Yet another reader referred to Georges Polti's The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations as the definitive listing of dramatic possibilities (Figure 10-1). Written in French and copyrighted in an English translation in 1921, this hard-to-find book is a seminal analysis of dramaturgy. Polti lists each situation of human conflict with its elements, plus wonderfully categorized examples and variations. Here, to whet your appetite, are the situations and elements.

Lists like this may seem limiting, but myths, conflicts, and themes are the DNA of human experience. Human beings will never stop enacting them and will never stop needing stories that explore their implications. You could make a long list of films for every one of the 36 situations noted in Figure 10-1. Most films contain multiples of the basic situations.

Once you know which situations and theme (or themes) your script is handling, you can look up its collaterals. This will certainly give you ideas about modifications or additions. These are unlikely to change the nature or individuality of your piece; instead, you are more likely to find and overcome your piece's weaknesses. Merely examining and testing the fabric of your story will toughen it and increase your authority as its director.

THE HERO'S JOURNEY

The lifetime work of Joseph Campbell, author of The Mythic Image, The Masks of God, and The Hero with a Thousand Faces, was to collect myths and folk tales from every imaginable culture and reveal their common, symbolic denominators. “The hero,” he says, “is the [person] of self-achieved submission.” The terms of this submission may vary, but they reflect that “within the soul, within the body social, there must be—if we are to experience long survival—a continuous recurrence of birth (palingenesia) to nullify the unremitting recurrences of death” (The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1972, p. 16).

Campbell recognizes that the hero's journey (he also means heroine's) always deals with a central character's struggle for regeneration against the forces of darkness. My purpose here is not to summarize his work, but to draw your attention to its profound implications for the makers of screen works. Just as Stanislavski found the psychological and practical elements of acting from studying successful actors, Campbell discovered the recurring spiritual and narrative elements held in common by so many of the world's tales. If something you have created shares some of the archetype, you may find it useful to see what elements are missing and whether their inclusion would strengthen your story. Campbell alleges that the hero generally makes a circular journey during his or her transformation. It includes departure, initiation, and return. You could apply this principle to a child going to her first day of school or to a cosmonaut making the first journey to a distant planet. Both go through severe trials and return changed.

A few of Campbell's chapter headings in Hero with a Thousand Faces show just how flexibly his analysis fits many film ideas:

Departure

The Call to Adventure

The Refusal of the Call

Supernatural Aid

The Crossing of the First Threshold

The Belly of the Whale

Initiation

The Road of Trials

The Meeting with the Goddess

Woman as the Temptress

Atonement with the Father

Apotheosis

The Ultimate Boon

Refusal of the Return

The Magic Flight

Rescue from Without

The Crossing of the Return Threshold

Master of the Two Worlds

Freedom to Live

If this calls to you, read it for yourself. If you would like to apply the ideas directly to a screen work without getting lost in the fascinations of world literature, look into Christopher Vogler's The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Storytellers and Screenwriters (California: Michael Wiese Productions, 1998). This is an intelligent and well-written book by an experienced story analyst. Vogler's enthusiasm, his many examples from classic and contemporary films, his willingness to share everything he knows with the reader, and his ability to keep the reader focused on the larger picture of human endeavor make this an unusually useful book. Vogler concludes by saying, “The beauty of the Hero's Journey model is that it not only describes a pattern in myths and fairytales, but it's also an accurate map of the territory one must travel to become a writer or for that matter, a human being.”

CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT PROBLEMS

A common problem is the character who refuses to develop and becomes a bore even to his creator. This usually happens because characters are being conceived to illustrate ideas rather than to dramatize situations, that is, to struggle with issues and conflicts. Contrast this with what Stuart Dybek says in introduction to his story “We Didn't,” published in Best American Short Stories 1994 (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1994). “As image begot anecdote, and as anecdote begot characters, I decided to let the characters take over and tell their story. They would have anyway, whether I'd let them or not.” Commonly authors feel like servants to their characters, but this can only happen when the characters are charged up with needs and desires that render them highly active. By the way, the annual Best American Short Stories book always contains superb and inspiring examples of short (and not-so-short) tales.

What to do when the characters are grounded?

Volition: Find out what the characters want, and what they are trying to get or do. Note for each scene what they should be trying to get from each other or from their situation.

Contradictions: All interesting characters contain conflict and contradictory elements. It's always what you can't reconcile in someone that makes them interesting.

Flaws: Each major character should have some interesting character flaws. The definition of a tragic figure is, after all, a character of magnitude with a fatal flaw. Flaws don't have to be fatal and characters don't have to be tragic, but they should be fresh, interesting, and above all, active.

Vital mismatches: One way to guarantee conflict is to make each character a different personality type.

- Astrology offers a whole system of personality types and destinies that can jolt your thinking and help you break out of monolithic characterization.

- Another system is that of the Enneagram, an ancient Sufi psychological system. Don Richard Riso and Russ Hudson's Personality Types (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1990) outlines the system and considers character in terms of nine basic types: the reformer, the helper, the status seeker, the artist, the thinker, the loyalist, the generalist, the leader, and the peacemaker. Each type is broken down by healthy and unhealthy characteristics, all offering a wealth of insight and developmental possibility for the screenwriter.

- Go to www.amazon.com and look up “personality types” among book titles, and you will find a wide range of choices.

THE MOST COMMON FLAW

The research I've cited previously—focusing as it does on the paradigms of drama—further confirms what all the screenwriting manuals proclaim: that above everything, the central characters must be active, doing, seeking, and therefore in conflict, rather than illustrative, passive, or acted upon.

In my experience this screenplay failure can be traced to a writer's limited concept of self. These writers see themselves (and therefore their point-of-view character) as someone acted upon, someone unable to significantly influence his or her destiny. When this is how you see yourself, you are going to create characters in that mold. In these scripts, if something good happens it is because of good luck rather than something earned by a character's actions. If something bad happens, it is because bad things always happen to good people.

Why is the culture of passivity so pervasive? Maybe it's because our collective unconscious was formed by ancestors living under intense subjection, who believed they must never antagonize “them,” the powerful. Even the lack of facial affect in some cultures can, I suspect, be traced to forms of slavery. Any expression of feeling implied independence and led to punishment.

Growing up myself in a nation still tied to feudal attitudes toward authority and knowing that a part of myself is conditioned to passive victimhood, I have pondered this question often, both personally and professionally. As a European, I was accultured to a fatalism that is anathema to Americans. At a Munich film conference, a delegate complained about the Americans taking over the European film market. Another speaker said it was because European films were too boring, and “because we don't know how to tell a story.” It set me thinking about storytelling and about the polarity between free will and fatalism.

Why do world audiences prefer Hollywood fables? This cannot be explained any longer as an international capitalist conspiracy. Surely the implications are more complex and interesting. Humankind has always had to resist being overcome by fatalism, and maybe as populations grew and the stress of competition increased, our sense of insignificance and powerlessness grew, too. Religion helped us deal with this until Darwin convinced us we were just another species fighting to survive, red in tooth and claw. The growth of the anti-globalization movement shows how outraged people feel at being exploited as consumers by global sales systems controlled somewhere else by “them” in business suits. Joseph Campbell's work argues that secular narrative evolved to help the individual fight back against feelings of powerlessness. Tales about heroes remind both teller and listener that an individual has potential. But notice that until the 20th century, regeneration was never accorded anyone who ignored the moral laws of the universe.

An immigrant civilization like the United States, trying nobly to function under its extraordinarily visionary constitution, is by historic accident a laboratory of these values—and of their antitheses. Free will is an article of faith with Americans. An old-worlder like myself, married to an American, will frequently play out the profound philosophical differences; under pressure I hide behind irony and what I imagine to be elegant fatalism. My American wife's instinct is to move to combat and overcome the circumstances. A small example: When I am ill, I generally accept what the hospital says it can do for me. But my wife goes into battle armed with pointed questions. Guess who uses more energy, and guess who gets better results from institutions?

The central question here is of great moment to writers: Do your characters accept circumstances or do they struggle against them? Neither course taken heedlessly will yield better consequences. Revolution can be tragic and so can tractability. So perhaps the energy of self-willed heroes comes as refreshment to civilizations weary from bowing to successive tyrannies. Somehow the better part of the American entertainment industry, so often led by immigrants with the energy and courage to reject the circumstances of their birth, has always offered visions—spurious or otherwise—of escape and moral triumph. How strange that this energy and optimism, widely equated with American immaturity, is the very nourishment found in the world's folk tales.

Dramaturgy is the art of orchestrating the contest of moral and emotional forces. For the competition to be serious, the contest must be balanced, as in Agnieszka Holland's Europa, Europa (1991), in which the young Solomon Perel repeatedly escapes the dark force of his Nazi tormentors by a combination of luck and inspired ingenuity. Less experienced writers creating from unexamined assumptions about passivity and victimhood deprive their audience of any true conflict. When you next examine a piece of screen writing, do the following:

- Assess each scene for what the main characters are trying to do or get, and summarize it each time as a tag description in the margin.

- Survey the whole constituted by these tags alone and the movement they create.

- Use the tools describing archetypes to help see deeper into the underlying dramatic structure.

- Mend and re-energize what is deficient.

THE ETHICS OF REPRESENTATION

Acquiring the education to make films is expensive, so most of those who make it into the film industry are from the comfortable middle classes. The result is that a nation's feature film output, with few exceptions, tends to represent as “normal” only what the privileged see as such. Anybody lucky enough to make movies for a living has a certain kind of power, and power used responsibly is power used for the greater good. Fiction filmmakers should sometimes speak for those without a voice and should certainly be careful not to perpetuate stereotypes. In documentaries this obligation is obvious, in fiction less so.

All storytelling begins from assumptions about what will be familiar and acceptable to the audience. Look back a few decades and see how many people, roles, and relationships in movies are represented in archaic or even insulting ways, though they excited little remark at the time. Women appear as secretaries, nurses, teachers, mothers, or seductresses. People of color are servants, vagrants, or objects of pity with little to say for themselves. Criminals or gangsters are ethnically branded, and so on—all this is very familiar. These stereotypes come from what some film faculty members at the University of Southern California call embedded values, or values so natural to the makers of a film that they pass below the radar of awareness. Jed Dannenbaum, Carroll Hodge, and Doe Mayer of USC's School of Cinema and Television have an excellent book, Creative Filmmaking-From the Inside Out: Five Keys to the Art of Making Inspired Movies and Television (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003). One section of the book poses some fascinating questions that I have adapted below.

Embedded values, easy to see in another field, creep into our own work with surprising ease. The point is not learning to be politically correct, which is just another kind of suffocation, but to avoid feeding into whatever is still “normal” and just shouldn't be. Take a few steps back and consider how your script represents what is listed below and whether the world in your script would look stereotypical or credibly complex on the screen to an astute person from another culture. This is particularly addressed to filmmakers of the First World whose preoccupations circle the globe, causing bitterness and even hatred.

Characters:

Class: What class or classes do they come from? How are differences handled? How are other classes represented?

Wealth: Do they have money? How is it regarded? How do they handle it? What is taken for granted? Are things as they should be, and if not, how well does the film express this?

Appearances: Are appearances reliable or misleading? How important are appearances? Do the characters have difficulty reading each other's appearances?

Background: Is there any diversity of race or other background and how is this handled? Do other races or ethnicities have minor or major parts?

Belongings: Do we see the characters work or know how they sustain their lifestyle? Do their clothes, appliances, and cars belong with their characters' breadwinning ability? What do their belongings say about their tastes and values? Is anyone in the film critical of this?

Talismans: Are there important objects, and what is their significance?

Work: Do the characters seem skilled and expert enough? Are they capable of sustaining the work they purportedly do?

Valuation: For what are characters valued by other characters? Does the film question this or cast doubt on the inter-character values?

Speech: What do you learn from the vocabulary of each? What makes the way each thinks and talks different from the others? What does it betray?

Roles: What roles do characters fall into, and do they emerge as complex enough to challenge any stereotypes?

Sexuality: If sexuality is present, is there a range of expression and how is it portrayed? Is it allied with affection, tenderness, and love? Or is it shown as disembodied lust? Is it true to your experience?

Volition: Who is able to change his or her situation and who seems unable to take action? What are the patterns behind this?

Competence: Who is competent and who not? What determines this?

Environment:

Place: Do we know where characters come from and what values are associated with their origins?

Settings: Will they look credible and add to what we know about the characters?

Time: What values are associated with the period chosen for the setting?

Home: Do the characters seem at home? What do they have around them to signify any journeys or accomplishments they have made?

Work: Do they seem to belong there, and how is the workplace portrayed? What does it say about the characters?

Family Dynamics:

Structure: What structure emerges? Do characters treat it as normal or abnormal? Is anyone critical of the family structure?

Relationships: How are relationships between members and between generations portrayed?

Roles: Are roles in the family fixed or do they develop? Are they healthy or unhealthy? Who in the family is critical? Who is branded as “good” or “successful” by the family, and who “bad” or “failed”?

Power: Could there be another structure? Is power handled in a healthy or unhealthy way? What is the relationship of earning money to power in the family?

Authority:

Gender: Which gender is shown to have the most authority? Does one gender dominate, and if so, why?

Initiation: Who initiates the events in the film, and why? Who resolves them?

Respect: How are figures with power depicted? How are institutions and institutional power depicted? Are they simple or complex, and does the script reflect your experience of the real thing?

Conflict: How are conflicts negotiated? What does the film say about conflict and its resolution? Who wins, and why?

Violence: Who is violent and why? What does it say about your values that you let them settle something this way?

In Total:

Criticism: How critical is the film toward what its characters do or don't do? How much does it tell us about what's wrong? Can we hope to see one of the characters coming to grips with this?

Approval/Disapproval: What does the film approve of, and is there anything risky and unusual in what it defends? Is the film challenging its audience's assumptions and expectations, or just feeding into them?

World View: If this is a microcosm, what does it say about the balance of forces in the larger world of which it is a fragment?

Moral Stance: What shape does the film's belief system take in relation to privilege, willpower, tradition, inheritance, power, initiative, God, luck, coincidence, etc.? Is this what you want?

Making fiction is proposing reality, and this is as true for fantasy as it is for realism. Films about chainsaw massacres or teenage shooting rampages gradually alter the threshold of reality for those attracted to such subjects, as a rash of high school shootings has demonstrated internationally. What do you want to contribute to the world? Are the elements you are using working as you desire?

These considerations are at the core of screen authorship, and Creative Filmmaking-From the Inside Out has some very pertinent ideas. It asks not that you change what you wish to say, but that you know and take responsibility for the ethical and moral implications of your work.

FUNDRAISING AND WRITING THE PROSPECTUS

Raising funds for a production is a special area of writing that varies greatly according to the scale of the production and the intended market for the film. To attempt covering it adequately would greatly increase the size of this book, which instead concentrates on the conceptual side of fiction filmmaking. There is, however, a written presentation that very much affects your success at arousing interest and raising funds, no matter how you go about it. This is the prospectus, a presentation package or portfolio you put together that communicates your project, its purposes, and personnel to prospective funders. It should create enthusiasm not by waxing lyrical, but through the eloquence of the arguments and detail it presents. It should be as personable, word perfect, graphic, and tasteful as something that would make you linger in a bookstore. It should contain the following:

Cover Letter: This succinctly communicates the nature of the film, its budget, the capital you want to raise, and what you want from the addressee. If you are targeting many small investors, this may have to be a general letter, but wherever possible, fashion a specific letter to a specific individual.

Title Page: Finding a good title usually takes inordinate effort but does more than anything to arouse respect and interest. An evocative photo or other professional-looking artwork here and elsewhere in the prospectus can also do much to make your presentation exciting and professional.

One-liner: A simple, compact declaration of the project. Some examples:

- A woman in a small New England town who discovers that her husband is gay must start a new life and conquer what it means to be alone.

- Four 12-year-old friends cut school for a day to find a home for a pony they mistakenly think is unwanted.

- A 40-year-old man conspires to leave his possessive mother and marry the woman of his dreams—who is in prison for something she didn't do.

Synopsis: Brief recounting of the story that captures its flavor and style.

History and Background: How and why the project evolved and why you feel compelled to make this particular film. Here is the place to establish your commitment.

Research: Outline what research you've done and what it contributes. Include stills of locations or actors that will help establish the look of your film. This is the opportunity to establish the factual foundation to the film if there is one, as well as its characters and their context. If special cooperation, rights, or permissions are involved, you should assure the reader that you've secured them.

Budget: Summary of main expected expenditures. Don't understate or underestimate—it makes you look amateur and leaves you asking for too little.

Schedule: Day-by-day plan for shooting period and preferred starting dates.

Cast: Pictures and resumes of intended cast members, paying special attention to their prior credits.

Resumes of Creative Personnel: In brief paragraphs, name the main creative personnel and summarize their qualifications. Append a one-page resume from each. Your aim is to present the team as professional, committed, exciting, and specially suited.

Copy of Screenplay: This is optional because most potential investors don't have the expertise to make sense of a barebones screenplay. The fact that it exists and looks fully professional may be a deciding factor for some. If it's an adaptation, be explicit that you have secured the rights to film it.

Audience and Market: Say what particular audience the film is intended for, and outline a distribution plan to show the film has a waiting audience. Copies of letters of interest from distributors or other interested parties are helpful here.

Financial Statement: Outline your financial identity as a company or group, make an estimate of income based on the distribution plan, and say if you are a not-for-profit company, or working through one, because this may permit investors to claim tax breaks.

Means of Transferring Funds: To save potential investors from having to compose a letter, enclose a sample letter from an investor to your company that commits funds to your production account.

If you approach foundations or other funding agencies, bear in mind that:

- Each is likely to have its preferred form of presentation.

- You should research the fund's identity and track record to know how best to present your work.

- Every grant application is potentially the beginning of a lengthy relationship, so your prospectus and whatever else you send should be consistent and professional in tone.

- Always write to a named individual and include a reprise of your project and your history with them to date.

- Though each prospectus is tailored for different addressees, be careful not to promise different things to different people.

- Your prospectus should have professional-looking graphics and typesetting.

- Have everything triple-checked for spelling or other errors. At this stage you are what you write, so secure desktop publishing facilities, and use the best available stationery.