CHAPTER 12

POINT OF VIEW

A point of view (POV) shot in film is a view from a character's physical location in the scene. But film has its own version of literary point of view: a set of more diffuse and empathic impressions experienced by an audience sharing a character's feelings. The effect is easy to describe, but it is harder to say how it came about. Harder still is to write, direct, and control it. This is because, unlike literature, the screen communicates in multiple ways. The printed page at least stands still as you analyze it, while film language is a complex interplay of moving images accompanied by the infinite modifiers of words, symbols, sounds, color, movement, and music. How all this interacts in our minds is simply beyond verbal analysis and formulation, as semiotic analysts found out.

But however indirect POV may be on the screen, it remains within your influence, and you will need to have some ideas and intentions about controlling it. For some helpful parallels, let's first look at how point of view works in the older and better-understood medium of writing.

POINT OF VIEW IN LITERATURE

In literature there are two basic sources for a story's narrating POV. One is omniscient and comes from the storyteller who is outside the story, while the other is by way of a character within the story.

OMNISCIENT

The omniscient storyteller, like God, has unrestricted movement in time and place, and can look into every aspect of the characters' past, present, and future. The Omniscient Storyteller can even address the reader directly. There are some variations:

- The self-effacing storyteller who shows the tale without comment, remains essentially characterless, and by so doing encourages us to make our own interpretation.

- The character within the story who has omniscient powers. This is easier to accept when the tale is in the past tense because the “tall tale” convention permits the narrator to affect greater knowledge and ability than would be credible in the events' present.

CHARACTER WITHIN THE STORY

A character within the story offers a more partisan and limited perspective routed through what characters in the tale experience, see, hear, and understand.

- The naïve narrator is someone (like Forrest Gump) who doesn't understand all the implications of his or her situation.

- The knowing narrator may pretend naïveté but be more acute than he or she lets on.

- The epic hero is at the sharp end of competency—someone such as Homer's Odysseus or Superman—who is cunning, heroic, or superhuman in some other way. In film noir the epic hero is typically the cool detective whose only vulnerability is a pretty woman in trouble.

TYPES OF NARRATIVE AND NARRATIVE TENSION

There are two classes of narrative in literature:

- Simple narrative, which is primarily functional and supplies an exposition of events, usually in chronological order. Simple narrative exists to inform.

- Plot-driven narrative, which may depart from chronology to reveal the events according to the story's type and plot strategy. Plot-driven narrative sets out to entertain by generating tension.

In literature, a rich source of tension lies between the story's elements and the attitudes the storyteller implies or manifests toward them. In all storytelling, withholding information is an important way to generate tension.

POINT OF VIEW IN FILM

Screen language has some advantages over literature but also some major handicaps. Although the screen image's comprehensiveness allows it to set up a situation and a mood in seconds, thereby dispensing with literature's lengthy tracts of exposition, photography's indiscriminate inclusiveness presents the eye with a bewildering catalogue of detail. Part of the function of framing, camera movement, and editing is to keep the eye where it should be and to discourage it from wandering off into byways. When wandering is encouraged, as in Antonioni's L'Avventura (1959), the environment begins to overwhelm the characters.

To successfully disentangle the subject from a surfeit of detail, a film must therefore direct the audience's attention. A caricaturist would face the same problem if requested to work through life photography instead of line drawing. The “insistently descriptive nature of the film image,” as James Monaco puts it, “inundates both subject and subtext with irrelevant detail. Ideas and authorial clarity are therefore harder to achieve in film than in literature.” When I first saw Terence Malick's Days of Heaven (1978) in the cinema I saw a beautiful and moving film, but only by viewing it later on a television monitor did I fully grasp its underlying themes and allusions. The reduced image and greater prominence of sound allowed me to look into rather than at it.

Because cinema relies on montage to channel our attention, the natural strategy for its narrative style is an omniscient POV with occasional forays into individual characters' viewpoints. Indeed there is said to be only one pure character-within-the-film POV movie, the actor-director Robert Montgomery's 1947 mystery The Lady in the Lake, in which the camera is the detective Philip Marlowe and characters address the camera when talking to him. We see him only when he looks at himself in the mirror.

Fiction films need the advantages of omniscience, but since German Expressionist times, films have freely used the power of a psychologically subjective vantage point. It remains easier to imply what a character notices and feels than for the audience to explore what the character feels. Let's look at the variations in POV available to the filmmaker and examine their authorial implications.

CONTROLLING

The controlling point of view in a film is usually that of a central character. In Anna Karenina it would probably be Anna's but it could be Karenin's or anyone else's. In the novel Wuthering Heights, the story is ostensibly told by a sympathetic servant who acts as a surrogate mother in a motherless household.

Like literature, film often temporarily switches POV whenever the shift usefully augments the viewer's perceptions. This can be achieved through parallel action (cutting to another story happening concurrently) or by an angle or subjective coverage that places us with the alternate character. Still more subtly, the switch can be made by an interaction that invokes our sympathy and needs no attention-shifting technique such as a special angle or shot. POV is, after all, intended to create an empathic insight into a character's feelings and thoughts—it isn't only concerned with what he or she sees.

Some films, like Truffaut's Jules and Jim (1962) or Alan Pakula's Sophie's Choice (1982), use a character's first-person voice-over narration to drive the film and locate its focus. Where there is no verbal narration, the controlling POV is seldom made so obvious. More often such films follow the lead of omniscient literature and locate POV in the consciousness of the person or persons at the center of the work. An example is Lewis Carroll's Alice passing through the looking glass and entering a world of inverted logic that we experience from her perspective. To the child in us, Alice Through the Looking Glass's looming, swollen personages are alarming magnifications of those encountered in our own childhood. Alice's bizarre world takes most of our attention, but the way she copes with it helps us see empathically into her psyche. What she confronts, and how she deals with it, are the two sides of a single coin, which is why content and form are so inseparable.

This is more easily seen in Victor Fleming's The Wizard of Oz (1939). When Dorothy makes a journey, like Alice's, through a bewitched landscape, she is joined by the Lion, the Tin Man, and the Scarecrow—alter egos whom she inspires to continue but who represent the threatened aspects of Dorothy's Self. When she awakens at the end of the movie we understand that her dream has been the means of reordering aspects of herself. Oz is therefore the setting for an allegorical quest for selfhood in which she seeks answers she needs in her “real” life on the farm.

Alice and Dorothy, the locus of attention in their particular worlds, become surrogates for ourselves, each heroine acting as a lens of temperament. As so often in narrative, each character's journey begins after irreversibly crossing a threshold (as in Joseph Campbell's analysis of folk stories), each becomes a lens into their world, and each initiates, then passes, trials that prove essential to their maturity.

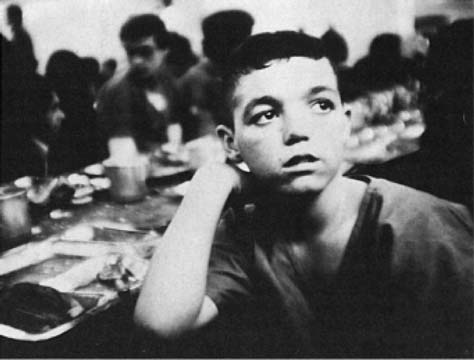

Many films establish powerful worlds through the eyes of vulnerable young people, notably de Sica's Bicycle Thief (1949), Ray's Pather Panchali (1954), Truffaut's 400 Blows (1959), Saura's Cria (1977), Schlöndorff's The Tin Drum (1979), Babenco's Pixote (1981) (Figure 12-1), Bergman's Fanny and Alexander (1983), John Boorman's Hope and Glory (1987), and many recent Iranian films, most notably those of Abbas Kiarastami. In the American cinema, M. Night Shyamalan's Sixth Sense (1999) is outstanding for the haunted state of mind of its 9-year-old central character, Cole.

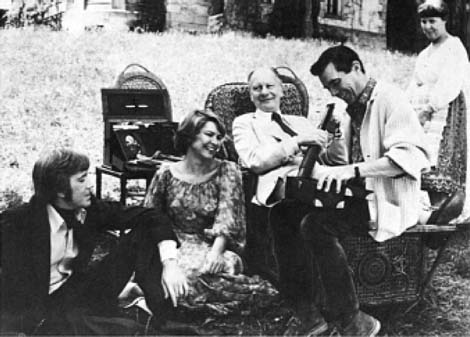

A few films that create powerful worlds through an adult's point of view are Truffaut's The Story of Adèle H. (1975), Resnais' Providence (1977) (Figure 12-2), Wenders' Paris, Texas (1984), Forman's Amadeus (1984), Paul Leduc's Frida (1987) (Figure 12-3), and Jane Campion's unnervingly visceral The Piano (1993).

VARIATIONS

POV variations show the physical viewpoint of a secondary character and elicit an alternative emotional understanding, that is, they make us feel what another character may be feeling at a particular moment. Good fiction brings minor characters alive, reminding us that they, too, have lives, feelings, and agendas to fulfill.

BIOGRAPHICAL

A biographical point of view implies the critical study of a central character who stands for larger qualities and ideas. Werner Herzog's Kasper Hauser (1974) focuses on the progress of a famous person who emerged after being kept isolated in a pig sty throughout his youth. The film's philosophical contentions emerge from Kasper's collisions with different small-town factions and by amassing a catalogue of their reactions. Boldly and poetically, the film imparts the violence of Kasper's sensations and the chaos of his inner life, beginning with a lyrical shot of a field of blowing corn. Over pastoral music a quotation is superimposed: “But can you not hear the dreadful screaming all around that people usually call silence?” At a stroke, Herzog establishes the juxtaposition of summer beauty and inner despair that will tear Kasper apart.

In the simple narrative sections we see Kasper objectively in his interactions with others, but Herzog's issue-driven plot and his use of music imply what Kasper feels and cause us to infer Kasper's subjective experience. Herzog the storyteller frames and juxtaposes these viewpoints and intersperses sections of textual quotation to imply that Kasper is an undefended and innocent Everyman. This makes an impassioned and poetical comparison between the nobility of a human's potential and the muddle and corruption we call civilization. What could be more movingly appropriate from someone who grew up in Nazi Germany?

CHARACTER WITHIN THE FILM

A film's apparent vantage point may come from a character within the film who directs us through the events, sometimes by narrating them. Some of the most moving guides are children. In Malick's Days of Heaven (1978) the fugitive's young sister provides voice-over narration. The country lawyer's daughter is the narrator of Mulligan's To Kill a Mockingbird (1963), and the boy houseguest writing in his diary narrates Losey's The Go-Between (1971). In Truffaut's Jules and Jim (1961) the narrator is a novelist and participant in the love triangle. His

limitations and distorted perceptions make us aware of his subjectivity and vulnerability, creating a rising sense of dramatic pressure. A character in extremity may perceive magic and monsters, and to portray these is really to dramatize that character's state of mind.

MAIN CHARACTER's IMPLIED POINT OF VIEW

Omniscient cinema characters and their issues are often established through a meaningful juxtaposition of realistic events. Their world is “normal” and undistorted by how they perceive it. The coolness and distance of this mode allow the audience to think as much as feel. Audience members long remain non-identifying observers but eventually merge with the main characters through empathy. Jiri Menzel's Closely Watched Trains (1966) is about a youth adapting to his first job in a railroad station. Obsessed by the shameful fact of his virginity, he finds himself surrounded by the sex lives of others. This seems more the humor of the gods than a situation he has influenced. Tony Richardson's A Taste of Honey (1961), on the other hand, focuses on a provincial teenager who gets pregnant at a time of great loneliness, is abandoned by the baby's father, and then is befriended for a while by a homosexual boy. As it shows how she is led by raw emotion from one situation to another, the film credits her destiny to the random interaction of environment, chance, and character. Her world, like that

of the young Czech railwayman, is still an alien environment with which she must struggle, but she bears more responsibility for her destiny. Strangely, this film (on which I worked as cutting room assistant) lost some of its documentary power in transition from the first raw material of the dailies to edited final version. Editing increases what we can see but fragments the inherent power of a moment.

Each of Hitchcock's two most famous films hinges on the fallibility of a POV character's judgment. In Rear Window (1954) an injured photographer confined to his room is compelled to look at the building opposite and becomes so convinced that a murder has taken place that he takes on some of the guilt of the murderer. In Psycho (1960) Marion Crane battles to deny her instincts that something malign is afoot in the Bates Motel. In each case, the audience must constantly decide the nature of reality in relation to appearances, until at the end Hitchcock provides the famous keys that unlock the suspense.

DUAL

In Malick's Badlands (1974), Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967), and Godard's Pierrot le Fou (1965), the subjects are partnerships and so there are two POV characters. All three films involve road journeys that end in self-destruction. In the two American films, the partnerships seem to exist to define male and female roles within a dissident or criminal subculture, while Godard's work uses the same self-immolating subculture as a vehicle to explore the incompatibilities between male and female psyches. Each film studies the tensions generated among characters and uses the way each step is (or is not) resolved to energize the next move. Pierrot le Fou in particular makes a rewarding study of dramatic form because character and dramatic tension are developed from action between the characters rather than from pressures applied externally by the chase.

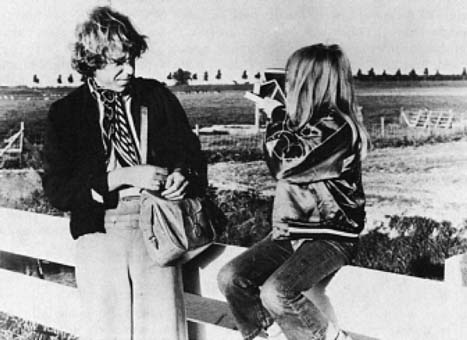

Wim Wenders' Alice in the Cities (1974) (Figure 12-4) is another journey, but the dialogue is between characters initially quite unequal: a 9-year-old girl and a reluctant journalist helping her search for her grandmother. Managing to avoid the pitfalls of kitsch sentiment, the film explores the initial gulf between adults and children. By creating two lost and uncertain characters of wonderful dignity, it shows how adults and children can achieve trust and emotional parity.

Multiple

In Alain Tanner's Jonah Who Will be 25 in the Year 2000 (1976), Altman's Nashville (1975), and later in his Gosford Park (2001), a dominant POV is

FIGURE 12-4

A child's and an adult's world compared in Wenders' Alice in the Cities (1974, courtesy Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archive).

deliberately excluded because each character exists as a fragment within a mosaic. All three films have a cast of characters reaching into double figures, and all focus on the patterns that emerge during a collective endeavor rather than on the consciousness and destiny of any individual. This concern with the flow and interaction of collective destiny can also be seen in Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction (1994) and Paul Thomas Anderson's Magnolia (1999). Both are concerned with coincidence and irony.

AUTHORIAL

A film's authorial POV is difficult to separate from its characters' individual points of view, but here, for the sake of argument, are three very different films—each dealing with ideas about humanity rather than the individuality of any protagonist. Orson Welles' Citizen Kane (1941) teases us with the enigma of a dead person's character by focusing on reporters trying to assemble a portrait of a deceased newspaper magnate. Charles Foster Kane is a mystery to be unraveled, a great man whose driving motives remain tantalizingly obscure to the little people in his shadow. Welles has a key to Kane's mood of unassuageable deprivation and shows it only to the audience. Through the symbol of a sled, epitomizing the loss of Kane's home as a boy, Welles clinches his argument that pain fuels human creativity.

Pedro Almodóvar's films have the common qualities of speeded-up farce, melodramatic plots, and a penchant for characters who seem to be parodying themselves. Yet among his druggie girls, harried housewives, battling lesbians, and streetwise prostitutes, there is a real humanity. In All About My Mother (1999) he focuses on a mother and teenage son whose father has become a transvestite prostitute. All of Almodóvar's customary circus takes place, but a clear and touching vision emerges of love between unlikely partners, with a message that kindness and loyalty are paramount even in a world of freaks.

Ethan and Joel Coen's O Brother Where Art Thou? (2000) takes the journey motif of Homer's Odyssey and makes it the story of escaped convicts in Depression-era Mississippi. The focus is on the epic hero who is able to wriggle out of every confrontation, including a memorable encounter with the Ku Klux Klan. Featuring a fabulous bluegrass music track, the film calls on every stereotype of the period to demonstrate how legends are spun.

These storyteller POV films, concerned with the mapping of cause and effect, employ characters to exemplify patterns of behavior rather than to be objects of sympathy, although of course we must sympathize with the characters to care about the ideas they exemplify. The same might be said of Hitchcock's films, which dwell on the subtle, misleading interplay of human constants rather than seeking to confer recognition on human individuality. Hitchcock is a polemicist whose passions are more of the head than the heart.

Where a director's intelligence and character are repeatedly stamped in a body of work, you can trace the recurring signs of vision and philosophy. This we think of as the directorial POV. Like that of a character, this POV may be interestingly polarized and in conflict. A storyteller like the novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald, who also wrote for Hollywood, may create a world of which he disapproves. Though Fitzgerald participated enthusiastically in the hedonism of the 1920s flapper generation, part of him loathed its privileges and egocentricity, and this ambivalence fuelled his writing. Such ambivalent critique by an artist is not unusual.

AUDIENCE

There is still another POV to be considered—that of the audience, which assesses the storyteller, his or her cinematic tale, and the assumptions the film expresses. To look at a patriotic World War II film is to experience an eerie gap between our values and those guiding the film. Individually and collectively, we as an audience have our own cultural and historical perspective into which we fit the entirety of an artwork. Enclosed with the work is the authorial frame of reference by which it was originally fashioned.

SUMMING UP

POV can be likened to the enclosing nature of Russian dolls.

- The audience's POV encloses the storyteller's (or film's) POV.

- The storyteller's POV encloses the characters' POV.

- The POV character's viewpoint embraces that of the subsidiary characters.

- Each character, however, holds up a mirror to the others.

POV emerges by default in run-of-the-mill films and results from the subject at hand and the idiosyncrasies of the actors and team that made the film. POV is difficult but important to bring under control, and probably the most practical approach is to think in terms of thematic statement and applied subjectivity. To expose this we might ask the following questions at any point while planning how to tell the tale:

- What belief or outlook does the story seek to express?

- From whom or what does this thematic concern emerge?

- Who is the main character and what makes him or her important?

- Whose mind is doing most of the seeing?

- What are the idiosyncrasies in the way they see?

- What disparity is revealed between their world and that of others?

- What is the function of a particular moment of subjective revelation?

This chapter discussed four different POV dimensions. Starting within the film frame and backing away toward the audience, we find them in the following order.

MAIN CHARACTER(S') OR CONTROLLING POINT OF VIEW

When shown from his or her POV, the main character's subjectivity affects the mood of both what is shown and how it is shown. This controlling POV influences both content and form of the film and shows up in a number of ways:

- It may be explicit, in the form of a character who speaks as a narrator to the audience.

- More often it is implicit, as the audience empathizes with a particular character or characters.

- Usually artful mise en scène (directing, scene design, and blocking) contributes heavily (see Chapter 29: Mise en Scène Basics).

- The film may feature a retrospective POV (the body of the film is perhaps a diary or memoir).

- A character may directly address the audience.

SUBSIDIARY CHARACTERS' POINTS OF VIEW

The subjectivity of subsidiary characters is called upon when useful to heighten or counterpoint that of the main character. Sometimes a movie lacks a central character or characters and concentrates on a texture of equal points of view.

AUTHORIAL OR STORYTELLER'S POINT OF VIEW

Authorship of a film is a collective effort, like that of an orchestra under a conductor, so the origin of authorial viewpoints remains uncertain. Authorial POV has two main polarities that often overlap:

- A personal or auteur POV may be the means by which the film expresses a central personality and attitude toward the characters and their story.

- Authorial POV may be vested more diffusely in the handling of archetypes and archetypal forms in genres such as the film noir or the western.

AUDIENCE POINT OF VIEW

This is the critical distance the audience senses between itself and the film. Films that seek to engulf the audience in sensation often manipulate the viewers to identify with (lose their identity in) a heroic figure and thus try to annihilate the audience's critical faculties. Other kinds of film follow the lead of Eisenstein (or Brecht in the theater) by stressing that the cinema is a construct, not a substitute reality. The polemicist blocks the spectators' tendency toward identifying and invites them instead to take on a heightened and critical awareness.