CHAPTER 14

STRUCTURE, PLOT, AND TIME

STRUCTURE

The definitive structure of a film results from the interplay of many considerations, starting with the script and its handling of time. However, during editing, a film may change drastically. Even the eventual shape of a single unit such as a sequence is determined late in the process by its dramatic content, composition, visual and aural rhythms, amount and complexity of movement within the frame, and length and placement of shots. Little of this can be more than hazily present in the filmmaker's mind at the outset. Therefore, the intention of this chapter is to deal only with the largest determinants of a movie's structure—plot, time, and thematic purpose.

Many filmmakers (though not general audiences) tend to resist the idea of a tightly plotted narrative because it can feel manipulative and contrived. When they find that screenwriting manuals prescribe three acts, each of a certain length, with page numbers specified for the plot points (points at which the story goes off at a tangent), many would-be screenwriters head for the hills. If such obsession with control over form seems reductive and formulaic, some context is missing from this picture. Nobody starts with the three-act form and the page numbers in mind. Writers begin with ideas, images, feelings, and perhaps some incidents in their own or a friend's life. The first draft may be in short story or outline form, or may be written as a treatment; every writer generates material however they can. Next, the writer figures out what problems the characters face and are trying to solve. This is usually very difficult, but once it is identified, the trajectory of a plot becomes clearer. Then the writer starts to story-edit using a dramatist's toolbox to spot the narrative elements and archetypes, and to assess how to increase their effectiveness.

These archetypes are as embedded in new stories as they are in old ones. Freud and Jung were highly conscious of them, and Joseph Campbell made it his life's work to trace them in world mythology and folk tales. Hollywood has come to similar conclusions by studying what audiences like. So much about film form is hotly debated, but, “if anything is natural,” says Dudley Andrew “it is the psychic lure of narrative, the drive to hold events in sequence, to traverse them, to come to an end” (Concepts in Film Theory, New York: Oxford University Press, 1984). There are narrative and so-called non-narrative approaches to storytelling, but non-narrative cinema is not without structure. Consider this from a review of Richard Linklater's Slacker (1991):

An original, narratively innovative, low budget movie from the fringe, Slacker is a perfectly plotless work that tracks incidental moments in the lives of some one hundred characters who have made the bohemian side of Austin, Texas, their hangout of choice. … The two forces that hold the film together are its clear sense of place (specifically Austin, more generally college towns) and its intimate knowledge of a certain character type; the “slacker”. …. But the film's improvisatory, meandering style is actually carefully constructed. (James Pallot and the editors of The Movie Guide, New York: Perigee, 1995)

Slackers is artfully constructed to complement Linklater's ideas about his characters and their values, but there are innumerable ways to pattern drama. Traditional Indian drama, dance, and music is often structured by a sequence of moods. Peter Greenaway's A Zed and Two Noughts (1985), which is structured around an operatic concatenation of events taking place between characters who work in a zoo, interweaves Greenaway's favorite fascinations: numbers, coincidence, philology, painting, wildlife, decay, and taxonomies—just to mention a few of the topics that help structure this bizarre film.

As long as audiences consume films in a linear fashion, an organizing structure and a premise will be inescapable. The over-formal Hollywood structure is really a paradigm abstracted from experience in cinemas, and that happens—not surprisingly perhaps—to reflect developments in the public consumption of the other time arts (dance, theater, music, radio, and television). Some central organizing factor is essential, especially for the short film, which, like poetry, must accomplish much in a brief time.

PLOT

The plot of a drama is the design that arranges or patterns the incidents befalling the characters. Michael Roemer in Telling Stories (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 1995, p. 39) says plot is “devised or constructed to manipulate, entertain, move, and surprise the audience.” He equates the notion of plot with the sacred, the ineluctable rules of the universe against which the characters are fated to struggle. As proof of this, discussions about plot always seem to center on what is likely, what usually happens in such circumstances, and what, morally or ethically speaking, should happen.

Because a film cannot show everything that happens to its characters, it must select certain incidents and actions while implying a whole world outside its purview. By concentrating our attention, a film's plot therefore acts as a lens through which to focus authorial intentions.

The emphasis on plot may be light or heavy. Heavy plotting tends to stress the logical and deterministic side of life. In more character-driven drama, plot may be de-emphasized in favor of a looser and more episodic structure in which chance, randomness, and the imperatives of character play a larger part. When you develop an idea for a film, your sense of cause and effect in life is bound to be reflected in the type and degree of plotting you choose.

Though a film may ardently promote a theory of randomness in life, cause and effect cannot be random in regard to the language it must use. The relationships among shots, angles, characters, and environments in film language are fashioned according to film language precedents. And though you have some latitude to modify the language, there's no more randomness in the basics than with any other language. You have to use the rules of English if you are to be understood by English-speakers. Film language results from a historically developed collusion between filmmakers and audiences, but like all live languages, it is in evolution. Plot plays its part in the pact not just by reconciling the characters' motivations—why character A manipulates a confrontation with character B, for example—but by steering our attention to the issues at hand. It should also maintain the tension that keeps the movie moving forward by making us want to see more.

Because characters' temperaments largely determine their actions, plot must be consonant with character. Conversely, characters cannot be arbitrarily plugged into any plot because plot and character must work hand in hand. Certain characters do certain things, and unless this appears natural, the plot will be forced. As the story advances, each event must stand in logical and meaningful relationship to what went before and lead with seeming inevitability to what follows. Plot failures will be those weaknesses in the chain of logic that disrupt credibility and leave the audience confused or feeling cheated.

There is a distinction between how things happen in reality and what is permissible in drama. If in real life an oppressed, docile factory worker suddenly leaps to the center of a dangerous strike situation and averts a tragedy by delivering an inspired oratory, you will ponder what signs of latent genius his coworkers overlooked, but you cannot doubt it could happen. If, however, we base a fiction film on such material, our audience will reject this event as untrue to life. Because the film is fiction, we shall have to carefully rearrange or even add selected incidents to show that our hero's potential was visible (although nobody noticed it), and it took the pressure of particular events to free him up to realize it.

Common weaknesses found in plotting are an excessive reliance on coincidence, or on the deus ex machina, the improbable action or incident inserted to make things turn out right. Audiences sense when a dramatist forces a development in this way, so you must ask a great many searching questions of your screenplay to ensure that its plot is as tight and functional as good cabinetry and that each character is true to his or her nature.

The well-crafted plot has a sense of inevitable flow because it includes nothing gratuitous or facile. It generates a sense of energizing excitement, and each step—by obeying the logic of the characters and their situation—stimulates the spectator to actively speculate what will happen next. This desirable commodity, called forward momentum in dramaturgy, is something that everyone works hard to generate.

THEMATIC PURPOSE

The theme of a work is the topic of its discourse or representation. When directing, you need to be well aware of your film's intended final meaning or thematic purpose. Some features, meant for a materialist and secular audience, employ a realism that leaves little room for metaphysical suggestion, yet audiences—whether they know it or not—crave the resonance of deeper meanings and crave drama that contains the seeds of hope.

Former generations, reared on the allusions and poetry of religious texts, were more attuned to thinking on multiple levels, as also happens in repressive societies in which people get used to indirect communication and accustomed to sniffing out the veiled allusion smuggled past the nose of authority. The artist who wants to be noticed today must recapture this skill, which really means using poetic thinking to relay visions of what the world is or can be. Allegory and parable (from parabola, meaning curved plane or comparison) can hit a nerve in audiences very powerfully, as shown by Robert Zemeckis' otherwise predictable Forrest Gump (1994). Its theme is that the gods protect a man without guile, and all things eventually come right.

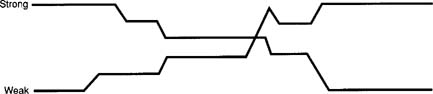

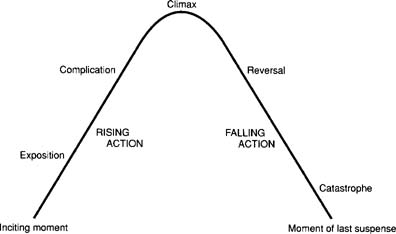

When considering the thematic purpose of a screenplay, it's helpful to fashion a graphic image or diagram to represent the movement of elements and characters in the story. The developmental curve for tragedy (Figure 14–1) is familiar to anyone who has studied dramaturgy, but you can create your own coordinates according to the story at hand. Figure 14–2 takes time as the horizontal axis and pressure on two characters as the vertical one, and it shows the development of an initially weak character in relation to a stronger one.

By making yourself translate from drama to a graph or other representation, you tackle the director's fundamental responsibility of making visible the film's underlying thesis, which can never be done except by deep and sustained

Figure 14–1

Development curve for the traditional tragedy.

thinking—something we all avoid. An image for The Wizard of Oz (1939) could come from the way each of the characters exerts—for good or ill—different pressures on Dorothy, who metaphorically speaking is like the hub at the center of a spoked wheel. Movement in the film is like a journey during which the wheel revolves a number of times, with each spoke bearing on her more than once. The image usefully organizes ideas about how The Wizard's thematic design applies a rotation of pressured experiences, each testing Dorothy's stamina and resourcefulness.

Drama put under pressure of inquiry will always yield additional thematic elements that cross-modulate within the larger pattern. Each work's full design emerges at the end of postproduction: A problem in editing turns out to be a misjudged scene that subtly disrupts and negates the overall pattern, and it must either be changed, moved, or eliminated. Often by discovering a disruptor, you establish harmony elsewhere, like one false note in an experimental chord progression that confirms by its wrongness the rightness of everything else.

Before you ever direct, make more than one detailed, written analysis of sequences or short films that move you (see Chapter 5: Seeing with a Moviemaker's Eye). True critical interaction will help enormously when you need to externalize the thematic development of a script you intend to film. During developmental work, follow the initial script, make a graphic representation of the whole film's changing pressures and development, and then write about it. As always, the act of writing will further develop what had initially seemed complete and devoid of further development potential. Defining a film's thematic progression in a script and representing it though action, symbol, and metaphor are major steps toward identifying a good structure for your film because theme and structure are symbiotic.

TIME

Every intended film has an optimal structure, one that will best represent the dramatic problem, its working out, and outcome. Arriving at it always involves deciding how to handle time. As with all design problems, less is more, and the simplest solution is usually the strongest.

LINEAR TIME

A linear time structure is one in which a film's sequences proceed through time in chronological order, though usually with unimportant passages removed. This produces a relatively cool, objective film because the narrative flow is not interrupted or redirected by plot intentions. Effect follows cause in a predictable and unchallenging arrangement.

Sometimes the conservative, linear approach does not do a story justice, though departing from it courts disorientation in your audience. Volker Schlöndorff's film of Heinrich Boll's novel The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (1975) abandoned the novel's flash-forward technique as too complex, substituting a conventionally linear structure that unfortunately muted the novel's contemplative, inquiring voice. What emerged was a polemical film in the Costa-Gavras tradition.

NONLINEAR TIME AND THE PAST

Frequently a story's chronology is disrupted and blocks of time are rearranged to answer the subjective priorities of a character's recall or because the storyteller has a narrative purpose for reordering time. Resnais, perennially fascinated by the way the human memory edits and distorts time, intercut Muriel (1963) with 8 mm movie material from the Algerian war to create a series of flashback memory evocations. In his earlier Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959), the French woman and her Japanese lover increasingly recall (or are invaded by) memories of their respective traumas—his, the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima; hers, a love affair with a German soldier in occupied France. These intrusions from the past are central to the present-day anguish suffered by each, and Resnais' premise implies that extreme lives are propelled by extreme trauma. The placing and frequency of these recollections indicate the movement of the characters' inner lives and provoke us into searching their developing love affair for what must be bringing these withheld memories to the surface. Both films pose questions about the effect of repressed personal history on present behavior.

NONLINEAR TIME AND THE FUTURE

A scene from the future can be a useful foreshadowing device. A familiar comedy routine illustrates this. After we see a man start walking, the film cuts ahead to a banana skin lying on the sidewalk. Cutting back and forth between the man and the banana skin creates expectation so that when he falls on it, we are in a state of receptive tension and laugh when chance takes its toll. We can subvert the expectation of the genre by making him step unaware over the banana skin at the point where the pratfall should occur.

Because the victim is unaware of the banana skin, the revelation of what threatens him necessarily arises from a storyteller's point of view, not that of the character. This is a game between storyteller and audience seemingly at the victim's expense, but turns out to be a joke on the audience. This, by the way, is a plot point. If instead the banana skin has been laid as a trap by a hidden boy, the flashing back and forth between victim and banana skin can only be the waiting boy's point of view and has become a piece of continuous present. Point of view here determines the tense of the footage.

In an example of dramatic foreshadowing, Jan Troell's Journey of the Eagle (1985) starts with unexplained shots of human bones in a deserted arctic encampment. The film is about an actual balloon voyage to the arctic at the turn of the century, a hastily prepared expedition that concluded with the death of the aviators. We see the actual aviators' fate first, then the fictional film reconstructing their tragic destiny.

Alain Tanner uses different foreshadowing in The Middle of the World (1974). The authorial narration at different stages counts down how many days remain in the affair we witness between the engineer and the waitress. Because the ending in both films is foreknown, our attention focuses on human aspiration and fallibility rather than, as it normally would, on whether the couple will stay together or the aviators will survive.

An interesting flash-forward technique is used in Nicholas Roeg's Don't Look Now (1974). The lovemaking scene is repeatedly intercut with shots of the couple getting dressed later in a state of abstraction. The effect is complex and poignant and suggests not only the idea of comfortable routine but also that each is preoccupied with what must be done after they have made love. The sequence implies that each act of love has not only a beginning, middle, and end, but a banal aftermath waiting to engulf it.

NONLINEAR TIME AND THE CONDITIONAL TENSE

A favorite device in comedy is to cut to an imagined or projected outcome, as in John Schlesinger's Billy Liar (1963), whose hero takes refuge from his dreary undertaker's job in fantasy. This technique is used altogether more somberly in Resnais' Last Year in Marienbad (1961), in which a man staying in a vast hotel tries to renew an affair with a woman who seems not to know him. Sometimes maddeningly experimental as it moves between past, present, and future, the film extends multiple versions of scenes to suggest repeated attempts by the central character to remember or imagine. Here Resnais uses film as a research medium and provides us with an expanded, slowed-down model of human consciousness at work on a problem.

TIME COMPRESSED

All time arts select and compress their materials in pursuit of intensified meaning, ironies exposed through juxtapositions, and brevity. Film does this supremely well. Presumably this came about because newsreels at the beginning of film history proved that audiences could infer the whole of something, such as a boat sinking, from key fragments of the action. The audience imagined not only what was between scenes and beyond the edges of the frame, but they inferred ideas from the dialectical tension among images, compositions, and subjects. Over the decades this film shorthand has become more concise as audiences and filmmakers evolve an ever more succinct understanding. Ironically, this process has been helped and accelerated by that thorn in our flesh, the TV commercial. In the cinema, Godard probably did more than anyone to demonstrate that cumbersome transitional devices were superfluous. Because the jump cut (already familiar from home movies) showed a time leap for a single cut or for a transition from one scene to the next, a more compressed overall editing style became inevitable. But narrative agility is useless if a film is otherwise based on a ponderous scripting style that over-explains and relies on hefty dialogue exchanges.

For a sustained narrative style that is elegant, compressed, and highly allusive, Jean-Pierre Jeunet's delightful Amalie (2002) uses every trick in the book. When the heroine must cut up paper, for instance, the camera shows her in comic fast motion. The script jump-cuts from scene to scene in tribute to the French New Wave cinema of earlier times that is clearly its inspiration.

American experimental cinema of the 1960s and 1970s rebelled against the conservatism of Hollywood and tried drastically altering assumptions about audience attention and the length of films and their parts. Eight hours of the Empire State Building made a statement at the long end of the spectrum, while Stan VanDerBeek's two-frame cuts and manic compression of scenes stand (or should I say streak) at the other. As the cinema has disentangled itself from television, the most conservative dramatic techniques have been left behind for the little screen and its older audience, though MTV and the advertising used to attract the consumer's attention has become demented. Cinema films have matured and are longer, more reliant on mood and emotional nuance, and less tied to the laborious plotting associated with screen narrative formulae.

The danger with too much narrative compression is the risk of distancing the audience from a developing involvement with personalities, situations, and ideas, and of generating a general, even ritualized drama, like the western serials that at one time dominated television. Compressing or even eliminating prosaic details should not simply allow makers to shoehorn ever more plot into a given time slot; it should make way for the expansion of what is significant. Here the Godard films of the early 1960s reign supreme.

TIME EXPANDED

The expansion of time onscreen allows a precious commodity often missing in real life—the opportunity to reflect in depth while something of significance is happening. Slow-motion cinematography is an easy way to do this, but we are a little tired of lovers endlessly floating toward each other's arms. The same hackneyed device bloated the race sequences of Hugh Hudson's Chariots of Fire (1981).

Yasujiro Ozu's Tokyo Story (1953) (Figure 14–3) and Michelangelo Antonioni's L'Avventura (1959) subverted the popular action form by slowing both the story and its presentation to expose the more subtle action within the characters. Both films center on the tenuousness of human relationships, something impossible to achieve with a torrent of action. Needless to say, an unattuned audience will find such films boring. L'Avventura was ridiculed at the Cannes Film Festival, but later found success in Paris and became a cornerstone in Antonioni's career.

OTHER WAYS TO HANDLE TIME

There is literal time, something seldom tackled in film form. Agnes Varda's Cleo from 5 to 7 (1961) shows exactly 2 hours in the life of a woman who has just learned she may be dying of cancer. Jafar Panahi's The White Balloon (1996)

shows a feisty 7-year-old going through one maneuver after another to get the goldfish she absolutely must have to celebrate the Iranian New Year. This film, too, is in real time, and Jonathan Rosenbaum thinks Panahi wanted to explore the difference between real time and subjective time—how long some experiences feel.

Christopher Nolan's Memento (2001), about a man with memory loss trying to piece his way backward to the moment of his wife's rape, is in retrograde time, or time played backward to a source point. Harold Ramis' very funny Groundhog Day (1993) contains a time loop. A jaded TV weatherman sent to witness the groundhog finds he is condemned to keep returning to the same key moment, each time learning a little more about himself, until finally he escapes a purged and happier man.

There is continuous time, or rather the illusion of it, in transparent cinema. This aims to rid its techniques of any evident cinematic contrivance. The appearance of real time masks the time expanded and time contracted behind the look of continuity. And there is parallel time, or parallel storytelling, as pioneered by D.W. Griffith, who acknowledged his debt in this regard to Dickens. Because the screen treatment of subjective experience is inseparable from perceived time and memory, there must be other designs for screen time yet to be explored.