CHAPTER 17

INTERPRETING THE SCRIPT

THE SCRIPT

If you have already made the step outline and concept as described in Chapter 7, you are coming to grips with the script's inner workings and practical implications. If you have not, do so now. Because the screenplay is skeletal and open to a wide spectrum of interpretation, you will need all the help you can get to assess its potential and build on it methodically and thoroughly.

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

If the screenplay is new to you, read it quickly and without interruption, noting your random first impressions. First impressions are intuitive and, like those about a new acquaintance, become significant as familiarity blunts your clarity. Define the film's premise and make sure you have an up-to-date step outline showing each sequence's function.

DETERMINE THE GIVENS

Reread the script and carefully determine the givens. This is your hard information directly specified in the screenplay. Givens include:

- Epoch

- Time of day

- Locations

- Character details revealed by their words and actions

- Clues to backstory (events prior to the period covered by the film)

- Words and actions used by characters

For each actor, for instance, the script provides everything known about the character's past and future. A character, after all, is like the proverbial iceberg—four-fifths out of sight. What is visible (that is, in the script) allows the actor to infer and develop what is below the “water line” (the character's biography, motives, volition, fears, ambitions, vulnerabilities, and so on). The givens are fixed and serve as the foundations determining everything else. Much is deliberately and wisely left unspecified, such as the movements and physical appearance of the characters and the treatment to be given the story in terms of camerawork, sound, and editing. The givens must be interpreted by director, cast, and crew, and the inferences each draws must eventually harmonize if the film is to be consistent.

BREAK INTO MANAGEABLE UNITS

Next, divide the script or treatment into workable units by acts, locations, and scenes. This helps you plan how each unit of the story must function and initiates the process of assembling a shooting script. If, for example, you have three scenes in the same day-care center, you will shoot them consecutively to conserve time and energy, even though they are widely spaced in the film. This will be laid out in the breakdown or crossplot (see Figure 17-4) described later in this chapter. When production begins, everyone must be well aware of the discontinuity among the three scenes or the actors may inadvertently adopt the same tone, and the camera crew may shoot and light them in the same way. In storytelling, you are always looking for ways to create a sense of contrast, change, and development.

PLAN TO TELL THE STORY THROUGH ACTION

Truly cinematic films remain largely comprehensible and dynamic even when the sound is turned off, so you should devise your screen presentation as if for a silent film. This will force you into telling your story cinematically rather than theatrically—that is, through action, setting, and behavior rather than through dialogue exchanges. This may require rewriting, which is a director's prerogative but most writers' idea of sabotage. Be sure to warn your writer of this likelihood well in advance. You don't want to find yourself battling your writer before you've even begun shooting.

DEFINING SUBTEXTS

You should keep in mind that every good text is a lifelike surface that hides deeper layers of meaning or subtext below. It reminds us that we are dramatists whose first purpose is to make evident the submerged significances flowing beneath life's surface. Much of the subtext arises out of what each character is really trying to do or get.

THE DISPLACEMENT PRINCIPLE

In life, people very rarely deal directly with the true source of their tensions. Characters often don't know themselves, or they keep what they do know hidden from other characters (remember life with your family?). What takes place is thus a displacement or an alternative to the characters' underlying desires. Two elderly men may be talking gloomily about the weather, but from what has gone before, or from telltale hints, we realize that one is adjusting to the death of a family member and the other is trying to bring up the subject of some money owed to him. Although what they say is that the heat and humidity might lead to a storm, what we infer is that Ted is enclosed by feelings of guilt and loss, while Harry is realizing that once again he cannot ask for the money he badly needs. This is the scene's subtext, which we can define as “Harry realizes he cannot bring himself to intrude his needs upon Ted at this moment and his situation is now desperate.” We cannot interpret the subtext here without knowledge gained from earlier scenes, and this emphasizes the degree to which well-conceived drama builds and interconnects its subtexts.

ESTABLISHING CHARACTERS AND MOTIVES

An important aspect of considering a script is to trace each event and character backward to see that the requisite groundwork has been laid. If a cousin arrives to show off a new car, and in so doing, reveals his uncle's plan to sell the family business, that cousin needs to be established earlier, and so does the family's dependence on the business. Drama that uses coincidence or wheels in a character purely for plot requirements looks shoddy and contrived. Like threads in cloth, you want to make your tapestry appear seamless and untailored.

AMBIVALENCE OR BEHAVIORAL CONTRADICTIONS

Intelligent drama exploits the way each character consciously or otherwise tries to control the situation, either to hide underlying intentions and concerns or, should the occasion demand it, to draw attention to them. Once, as director and actor, you know the subtexts, you can develop behaviors to manifest the tensions between inner and outer worlds, between what the character wants and what impedes him.

Ambivalences like these are clues to the audience about a character's hidden life and underlying conflicts. When actors begin to act on (not merely think about) their characters' conflicts and locked energies, scenes move beyond an illustrative notion of human interaction and begin to truly manifest the characters' tensions. The work now begins to imply the pressurized water table of human emotion below the aridly logical top surface. This underlying tension may demand preserving a logical exterior in which the character is rational, mannerly, and inscrutable. This is all part of how a person keeps their agendas hidden. We all do it, and most of the time.

BREAK THE SCREENPLAY INTO ACTS

To refresh your memory:

Act I Establishes the setup (characters, relationships, situation, and dominant problem faced by the central character or characters)

Act II Develops the complications in relationships as the central character struggles with the obstacles that prevent him or her from solving the main problem

Act III Intensifies the situation and resolves it, often in a climactic way that is emotionally satisfying

DEFINE A PREMISE OR THEMATIC PURPOSE

Another concept vitally important to the director is that of the thematic purpose, or superobjective, to use Stanislavski's concept. This is the authorial objective powering the work as a whole. You might say the superobjective of Orson Welles' Citizen Kane (1941) is to show that the child is father to the man, that the power-obsessed man's course through life is the consequence of childhood deprivation that no one around him ever understands.

However short your film, it is vital to define its thematic purpose while it remains in script form or you won't capitalize on the script's potential. Usually you have a strong intuition about what the thematic purpose is, but you should have it stated and to hand when you survey all the scene subtexts together. Sidestepping this brainwork will cost you dearly later.

To some degree, a script's thematic purpose is a subjective entity derived from the author's outlook and vision. In a work of some depth, neither the subtexts nor the thematic purpose are so limited that interpretive choices for the director and cast are fixed and immutable. Indeed, these choices are built into the way the reader reads and the audience reacts to a finished film because everyone interprets selectively what they see from a background of particular experiences. These are individual but also cultural and specific to the mood of the times.

Franz Kafka's disturbing story Metamorphosis—about a sick man who discovers he is turning into a cockroach—might be read as a parable about the changes people go through when dealing with the incurably sick or as a science fiction “what if” experiment that imprisons a human sensibility in the body of an insect. In the first example, the thematic purpose might be to show how utter dependency robs the subject of love and respect, while the second shows how compassion goes out to a suffering heart only when it beats inside a palatable body.

Whatever you choose as your thematic purpose, you absolutely must be able to articulate something interesting with utter conviction. It must be consistent with the text and stimulating to your creative collaborators. Superficial readings of the screenplay will produce divergent, contradictory interpretations, so you must shepherd your ensemble toward a shared understanding of the story's purpose or you won't have an integrated story. No matter how much work you put in, probing and intelligent actors will take you further into unexamined areas. That's part of the excitement of discovery.

GRAPHICS TO HELP REVEAL DRAMATIC DYNAMICS

Following are a couple of ways to expose the heart and soul of each scene. These methods for exposing what would otherwise remain undisturbed and unexamined are consciousness-raising techniques that allow the director to confront the implications of the material. They take time and energy to implement, but will repay your effort.

BLOCK DIAGRAM

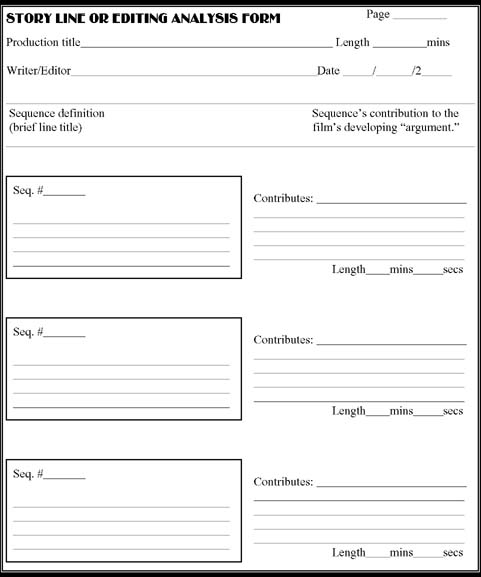

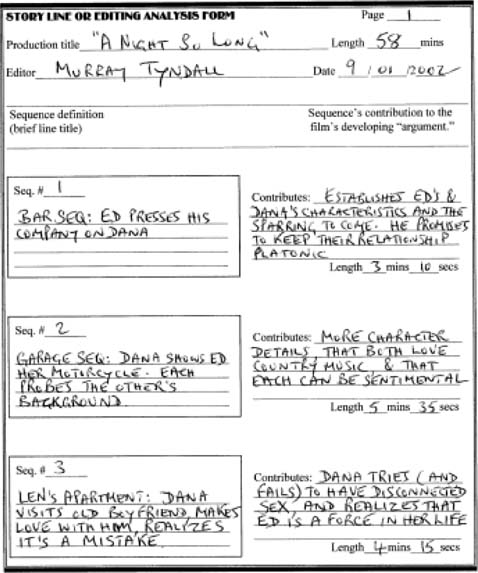

Make a flow chart of the movie's content, with each sequence as a block. To do this conveniently, photocopy the Story Line/Editing Analysis Form (Figure 17-1). In the box, name the scene, and under “Contributes” write two or three lines to describe what the audience will perceive as its dramatic contribution to the story line, as in Figure 17-2. This goes further than the step outline because it is predominantly concerned with dramatic effect rather than content. Expect to write descriptive tags concerning:

- Plot points

- Exposition (factual and setup information)

- Character definition

- Building mood or atmosphere

- Parallel storytelling

- Ironic juxtaposition

- Foreshadowing

Having to write so briefly makes you find the paradigm for each tag a brain-straining exercise of the utmost value. Soon you will have the whole screenplay diagrammed as a flow chart. You will be surprised by how much you learn about its structure and its strengths. The following are common weaknesses and their likely cures:

| Fault | Likely cure |

| Expository scenes that release information statically and without tension | Make the scene contribute action and movement to the story, not just factual information. You may need to drop the scene and bury the exposition in a more functional sequence. |

| Unnecessary repetition of information | Cut it out. However, some information may be so vital to the plot that you may want to cover yourself and only edit it out later if the audience proves not to need it. |

| Information released early or unnecessarily | Wilkie Collins said, “Make them laugh, make them cry, but make them wait.” Making the audience wait is axiomatic |

| for all drama, so it comes down to deciding how long. | |

| Factual information that comes too late | When an audience is unduly frustrated they may give up. Another judgment call. |

| Confusions in time progression | This can be disastrous. Better to be conservative in shooting, knowing you |

GRAPHING TENSION AND BEATS

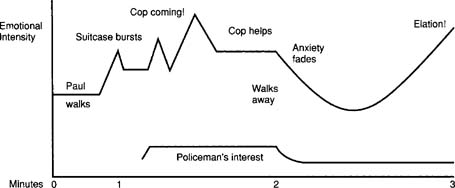

A good way to dig below a script's surface is to graph the changing emotional pressures or temperatures of each scene. Do it after several readings of the script and before you start work with the actors. If a scene remains problematic, it's good to graph it collaboratively with the actors after some initial rehearsal. Time is the graph's baseline and tension is the vertical axis. Do the overall scene in black, then use a different color for each main character. If, for instance, you have a comedy scene between a dentist and a frightened patient, you could graph the rise and fall of the patient's anxiety, then rehearse the action to progressively escalate the patient's fear and link to it the rising irritation of the dentist. Each dramatic unit within the scene culminates in a beat or moment of decisive realization for one or another of the characters. One such beat might take place in the reception area when the already nervous patient hears a yell from the surgery and decides to make a run for freedom once the receptionist's back is turned. Another might come when, finding she has already locked the door, he must face her contempt.

Before you begin shooting, make a barometric chart for your whole film's emotional dynamics. It won't be easy because you will have to designate graph coordinates to reflect the issues in your particular scene. You will be surprised at how much this reveals. I discovered why you need this exercise the hard way: in the cutting room when I found I had directed a film where scene after scene had surreptitiously adopted a uniform shape. They were simply restating the same emotional information.

As an example, here is a scene based on a wartime experience of my father's in World War II in London. Food was scarce and often acquired on the black market. Note that for a film treatment we put it into the present tense.

Paul is a sailor from the docks setting out for home across London. Onboard ship he has acquired a sack of brown sugar and is taking it home to his family. Food of all kinds is rationed, and what he is doing is very risky. He has the sugar inside a battered old suitcase. The sugar is as heavy as a corpse, but he contrives to walk lightly as though carrying only his service clothing. In a busy street one lock of the suitcase bursts, and the green canvas sack comes sagging into view. Dropping the suitcase hastily on the sidewalk he grips it between his knees in a panic while thinking what to do. To his horror, a grim-faced policeman approaches. Paul realizes that the policeman will check what's inside the suitcase, and Paul will go to prison. He's all ready to run away, but the policeman pulls some string out of his pocket and gets down on his knees, his nose within inches of the contraband, to help Paul tie it together. Paul keeps talking until the job's done, then thanking him profusely, picks up the suitcase as if it contained feathers and hurries away, feeling the cop is going to sadistically call him back. Two streets later he realizes he is free.

The graph in Figure 17-3 plots the intensity of each character's dominant emotion against the advance of time. Paul's emotions change, while the unaware policeman's are simple and placid by contrast. Paul's stages of development, roughly, are:

- Trying to walk normally to conceal weighty contraband

- Sense of catastrophe as suitcase bursts

- Assuming policeman is coming to arrest him

- Realizing his guilt is not yet apparent—all is not yet lost

- Tension while trying to keep policeman's attention off contents

- Making escape under policeman's ambiguous gaze

- Sense of joyous release as he realizes he's gotten away with it

Notice that the treatment contains some realizations that cannot be explicitly filmed without breaking the sequence into “what if” sequences where Paul imagines himself arrested, being tried, and being put in prison. Better would be to plant the consequences of thieving earlier in the action.

A visual like Figure 17-3 brings clarity to where and how changes in the dominant emotions must happen and shows:

- The need to create distinct rising and falling emotional pressures within the characters

- Where characters undergo major transitions or beats

- Where the cast must externalize beats through action

Clarifying the unfolding action in this way helps overcome a major problem with untrained actors: They often try to play all their character's characteristics all the time, no matter what is happening at any given moment. This muddies and confuses the playing and renders it an intellectual approach. Good playing deals with one situation and its attendant emotions at a time and finds credible ways to transition from one to the next. The director must often rein in actors and help them concentrate on the specifics of their character's consciousness, moment by moment.

In the scene above, the policeman feels only a mild, benign interest, which falls away as the sailor with the successfully mended suitcase goes on his way. It is a very different situation for Paul. He must pretend he's an innocent man with a luggage problem. Knowing something the policeman does not know, the audience empathizes with the sailor's anxiety and appreciates his efforts to project petty concerns. What is missing from the scene is the knowledge of (1) the nature of the contraband, (2) where he is going with it, and (3) what he risks if he is caught. For the scene to yield its full potential, all these plotting points would need to be established as exposition earlier.

POINT OF VIEW

We could add a dimension to our scene by underscoring Paul's subjectivity and raising the stakes of the scene. By having the policeman appear threatening as he approaches, we could make him seem to be testing Paul's guilt by offering to help. Only late in the scene would we reveal his benign motives. Camerawork juxtaposing the bulging, insecure suitcase against the approaching policeman would suggest visually the thoughts uppermost in Paul's mind.

Here we are trying to reveal Paul's point of view (POV), which means relaying evidence that makes us identify with him. By switching to the policeman's point of view, we can also investigate his reality and show the POV of an apparently unsympathetic character as well as that of our hero. This is an important departure from the good/evil dichotomy of the simple morality play where only the main character is a rounded portrait and subsidiary characters remain flat.

In my example the audience has been led to participate in Paul's inner experience while seeing all the time how he conceals what he is feeling. Actors and directors of long experience intuitively carry out this duality. The clarity and force of subjectivity revealed in this way will contribute much to a satisfying performance. For the novice actor lacking an instinct for this, nothing less than a detailed, moment-to-moment analysis with his director will enable him to effectively mold his character's consciousness at the core of the scene.

FATAL FLAW: THE GENERALIZED INTERPRETATION

Inexperienced players will, as I have said, approach a scene with a correct but generalized attitude gained from a reading or discussion. Applied like a color wash and without regard to localized detail, the unspecific, monolithic interpretation produces a scene that is fuzzy and muted where it should be sharp and forceful. When you see this as you direct, you will have to demand that each actor develop clear specific goals from moment to moment within each scene. You can get this by asking actors to speak their character's subtextual thoughts out loud, as in Project 22–3: “Improvising an Interior Monologue.” This may have to be done one-on-one so the actor does not feel humiliated in front of more experienced players. Be careful, by the way, that your role as coach is not appropriated by actors who consider themselves more experienced or you will soon have multiple directors.

CROSSPLOT OR SCRIPT BREAKDOWN IN PREPARATION FOR REHEARSAL

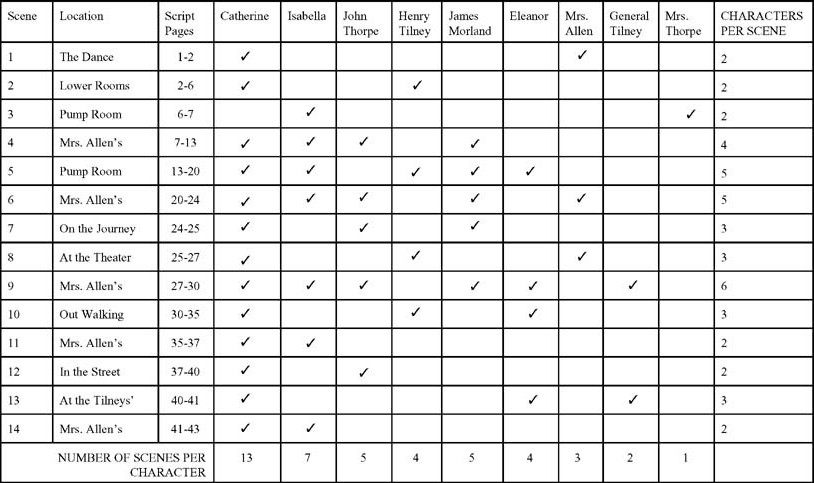

Take the script and make a breakdown of characters appearing in each scene, like the one in Figure 17-4 made for a treatment of Northanger Abbey. A scene breakdown like this, allowing you to see at a glance which scenes require which location and what combination of actors, will be essential for planning the rehearsal schedule and the eventual shoot. It also indicates the film's inherent pattern of interactions and is yet another aid to discovering the work's underlying structures.

FIRST TIMING

A film's length absolutely determines what festival or market it can enter. Television has strict length requirements, so learning to keep control over length is vital. Already you need to know how long the script will run. You can get a ballpark figure by allowing a minute of screen time per screenplay page. This should

average out across many pages but will not necessarily work for specific passages such as a rapid dialogue exchange or a succession of highly detailed images with long, slow camera movements. You can get a more reliable figure by reading over each scene aloud, acting all the lines, and going through the actions in imagination, or better, for real. Using a stopwatch, make a notation for each sequence, then add up the total.

Be aware that rehearsal and development invariably slows material by adding business not specified in the script. This kind of action must be present if the characters are to be credible and the film cinematic rather than theatrical. Make new timings periodically to avoid unpleasant surprises.

If rewriting makes a scene too long, re-examine every line of dialogue to see if newly developed action makes any of it redundant. Likewise, in rehearsal, never hesitate to cut a line if its content can be delivered by an action.