CHAPTER 43

EDITING FROM FINE CUT TO SOUND MIX

Sound is an incomparable stimulant to the audience's imagination and only rarely gets its due. Ideally everyone is alert to sound-composition possibilities from the moment the script begins to be written and keeps building on these concepts until postproduction ends. Opportunities and special moments arise in addition to those programmed in from the beginning, and this is part of a work asserting its identity. It's important to keep track of every idea for sound that anyone has along the way, and not leave it all to an audio-sweetening session. That, by the way, is an expression I detest. It suggests that sound is sour and needs sugaring. Sound design, sound editing, and sound mix are more direct and respectful terms. Especially if you have monitored and directed the sound treatment throughout, the sound mix will be a special and even exhilarating occasion.

What happens when sound is left to fend for itself? Poor handling of dialogue tracks alone will disrupt the dreamlike quality that a good film attains, so it's worth learning a lot about the handling of sound. Sound specialists will be the first to say they work most creatively with good groundwork from the director and script.

Finalizing sound is another computer operation, usually using ProTools and a first-rate amplifier and speaker system to replicate a hypothetical cinema's sound environment. I say hypothetical because few cinemas approach the state of the art. Yet good sound, as Dolby cinemas have discovered, is good business, so sound may yet get its day.

THE FINE CUT

With typical caution, filmmakers call the result of the evolutionary editing process the fine, not final, cut for there may still be minor changes and accommodations. Some of these arise from laying further sound tracks in preparation to produce a master mixed track.

MAKE A FINAL CHECK OF ALL SOURCE MATERIAL

As mentioned previously, the editor must, as a last act, view all shot material to make sure nothing useful has been overlooked. At this point in editing, and especially if there is a lot of coverage, this demand is skull-crackingly tedious and time-consuming, but almost invariably there will be some “Eureka!” discoveries in compensation. If there aren't, you can rest easy that night.

SOUND

SOUND DESIGN DISCUSSIONS

How and why music gets used needs careful discussion, as described in the previous chapter: Working with a Composer. Although sound is made of different elements—music, dialogue, atmospheres, effects—it is a mistake to put them in a hierarchy and think of them separately at this, the ultimate compositional stage.

Before the sound editor goes to work splitting dialogue tracks and laying sound effects, there should be a detailed discussion with the director about the sound identity of the whole film and how each sequence should be treated within this identity from the sound point of view. You should agree on the known sound problems and on a strategy to handle them. This should be a priority because dialogue reconstruction—if it's needed—is an expensive, specialized, and time-consuming business, and no film of any worth can survive the impact of having it done poorly.

Walter Murch, the doyen of editors and sound designers, makes a practice of watching a film he is editing without the sound turned on, so he imagines what the sound might properly be. Among the less-usual functions of sound, among many listed in Randy Thom's “Designing a Movie for Sound” (www.filmsound.org/articles/designing_for_sound.htm), are to:

- Indicate a historical period

- Indicate changes in time or geographical locale

- Connect otherwise unconnected ideas, characters, places, images, or moments

- Heighten ambiguity or diminish it

- Startle or soothe

That Web site, www.filmsound.org, is an excellent source of information for all aspects of sound in film, by the way.

Any good sound editor will tell you it's not quantities of sound or complexity that make a good sound track, but rather the psychological journey sound leads you on while you watch. This is the art of psychoacoustics, and usually sound is most effective when it is simple rather than complex, and highly specific and special rather than generic.

POST-SYNCHRONIZING DIALOGUE

Post-synchronizing dialogue means each actor creating new speech tracks in lip sync with an existing picture, and the laborious operation is variously called dubbing, looping, or automatic dialogue replacement (ADR). This is done in a studio with the actor or actors watching a screen or monitor and rehearsing with the picture before they get the OK to record. A long dialogue exchange will be done perhaps 30 seconds at a time.

The process is ardently to be avoided because newly recorded tracks invariably sound flat and dead in contrast to live location recordings. This is not because they lack background presence, which can always be added, or even because sound perspective and location acoustics are missing. What kills ADR is the artificial situation. The actor finds himself flying blind to reconstitute every few seconds of dialogue and completely in the hands of whomever is directing each few sentences. However good the whole, it invariably drags down the impression of their performances, and actors hate ADR with excellent reason.

THE FOLEY STAGE AND RECREATING SYNC SOUND EFFECTS

Many sound effects shot wild, on location, or in a Foley studio can be fitted afterward and will work just fine. The Foley studio was named after its intrepid inventor, Jack Foley, who realized back in the 1940s that you could mime all the right sounds to picture if you had a sound studio with different surfaces, materials, and props. As everyone now knows, it takes invention to create a sound that is right for the picture. Baking powder under compression in a sturdy plastic bag, for instance, makes the right scrunching sound of footsteps in snow, and a punched cabbage can sound most like someone being struck over the head.

A Foley studio has a variety of surfaces (concrete, heavy wood, light wood, carpet, linoleum, gravel, and so on. The Foley artists may add sand or paper to modify the sound of footsteps to suit what's on the screen. In the most forgettable Jayne Mansfield comedy, The Sheriff of Fractured Jaw (1959), directed by Raoul Walsh, my job was to make horse footsteps with coconuts and steam engine noises with a modified motorcycle engine. It was fun.

Repetitive sounds that must fit an action (knocking on a door, shoveling snow, or footsteps) can usually be recreated by recording the actions a little slower and then cutting out the requisite frames before each impact's attack. This is easy with a computer. More complex sync effects (two people walking through a quadrangle) will have to be post-synced just like dialogue, paying attention to the different surfaces the feet pass over (grass, gravel, concrete, etc.). Surviving a grueling series of post-sync sessions makes you truly understand two things: one, that it is vital for the location recordist to procure good original recordings if at all possible, and two, how good top-notch location film sound and editing crews really are at their jobs.

On a complex production with a big budget, the cost is economically justified. For the low-budget filmmaker, some improvisation can cut costs enormously. What matters is that sound effects are appropriate (always difficult to arrange) and that they are in sync with the action onscreen. Where and how you record them is not important provided they work well. Sometimes you can find appropriate sound effects in sound libraries, but never assume a sound effect listed in a library will work with your particular sequence until you have tried it against picture. By entering sound effects library in a search engine, you will turn up many sources of sound libraries. Some let you listen or even download effects. Try Sound Ideas at www.sound-ideas.com/bbc.html.

A caution: Most sound libraries are top heavy with garbage shot eons ago. Many effects tracks are not clean, that is, they come with a heavy ambient background or ineradicable system hiss. The exotic sounds such as helicopters, Bofors guns, and elephants rampaging through a Malaysian jungle are easy to use. It's the nitty-gritty sounds such as footsteps, door slams, dog growling, and so on that are so hard to find. At one time there were only six different gunshots used throughout the industry. I heard attempts at recording new ones. They were awful and sounded nothing like you would expect. Expectation is the key to getting it right. Authentic sounds are nowhere next to those you imagine and accept as the Real Thing.

SOUND CLICHÉS

Providing sounds for what is on the screen can easily be overdone. Because a cat walks across a kitchen is not an excuse for a cat meow, unless the cat is seen to be demanding its breakfast in a coming shot. Do look up this Web site for a hilarious list of sound clichés: www.filmsound.org/cliche/. In it all bicycles have bells; car tires must always squeal when the car turns, pulls away, or stops; storms start instantaneously; whistling types of wind are always used; doors always squeak; and much, much more.

WHAT THE SOUND MIX CAN DO

After the film has reached a fine cut, the culmination of the editing process is to prepare and mix the component sound tracks. A whole book could be written on this preeminent subject alone. What follows is a list of essentials along with some tips.

You are ready to mix tracks into one master track when you have:

- Finalized content of your film

- Fitted music

- Split dialogue tracks, grouping them by their equalization (EQ) needs and level commonality:

A separate track for each mike position in dialogue tracks

Sometimes a different track for each speaker, depending on how much EQ is necessary for each mike position on each character

- Filled-in backgrounds (missing sections of background ambience, so there are no dead spaces or abrupt background changes)

- Recorded and laid narration (if there is any)

- Recorded and laid sound effects and mood-setting atmospheres

- Finalized ProTools timeline contents

The mix procedure determines the following:

- Sound levels (such as between a dialogue foreground voice track and a background of a noisy factory scene if, and only if, they are on separate tracks)

- Equalization (the filtering and profiling of individual tracks either to match others or to create maximum intelligibility, listener appeal, or ear comfort; a voice track with a rumbly traffic background can, for instance, be much improved by rolling off the lower frequencies, leaving the voice range intact)

- Consistent quality (for example, two tracks from two angles on the same speaker will need careful equalization and level adjustments if they are not to sound dissimilar)

- Level changes (fade up, fade down, sound dissolves, and level adjustments to accommodate sound perspective and such new track elements as narration, music, or interior monologue)

- Sound processing (adding echo, reverberation, telephone effect, etc.)

- Dynamic range (a compressor squeezes the broad dynamic range of a movie into the narrow range favored in TV transmission; a limiter leaves the main range alone but limits peaks to a preset level)

- Perspective (to some degree, equalization and level manipulation can mimic perspective changes, thus helping create a sense of space and dimensionality through sound)

- Multi-channel sound distribution (if a stereo track or surround sound treatment is being developed, different elements go to each sound channel to create a sense of horizontal spread and sound space)

- Noise reduction (Dolby and other noise-reduction systems help minimize the system hiss that would intrude on quiet passages)

Be aware that when old technology must be used, changes on a manually operated mixing board cannot be done instantaneously on a cut from one sequence to the next. Tracks must be checkerboarded (meaning they alternate from track to track) so that a channel's equalization and level adjustments can be set up in the section of silent sound spacing prior to the track's arrival. This is most critical when balancing dialogue tracks, as explained in the following section.

SOUND MIX PREPARATION

Track elements are presented here in the conventional hierarchy of importance, although the order may vary; music, for instance, might be faded up to the foreground and dialogue played almost inaudibly low. When cutting and laying sound tracks, be careful not to cut off the barely audible tail of a decaying sound or to clip the attack. Sound editing should be done at high volume so you hear everything that is there or isn't there when it should be.

Laying nonlinear digital tracks is much easier than in the old manual days because you follow a logic that is visible to the eye and can hear your work immediately. Fine control is quick and easy with a sound-editing program such as ProTools because you can edit with surgical precision, even within a syllable. The equivalent operation in manual film is not difficult but you cannot properly hear the results until mix time. Traditional mix theaters are nowadays about as common as steam trains, and there is not much weeping over their loss. Getting dozens of tracks laid for a mix was a monumental task, and watching them churn to and fro in 30 dubbing players slaved to a film projector was stressful (my first job was cement splicing in a feature film studio). Twelve people worked a day or more to mix 10 minutes of film track. For battle sequences or other complex situations, you could multiply that period several times. Some battles did not stay on the screen, either.

NARRATION OR VOICE-OVER

Getting actors to make a written narration sound spontaneous is next to impossible, so consider using the improv method in which actors, given a list of particular points to be made, improvise dialogue in character. By judicious side coaching, or even interviewing, the actor produces a quantity of entirely spontaneous material in a number of passes that can be edited down. Though labor-intensive, the result will be more spontaneous and natural than anything read from a script.

If you lay narration or interior monologue you will need to fill gaps between narration sections with room tone so the track remains live, particularly during a quiet sequence.

DIALOGUE TRACKS AND THE PROBLEM OF INCONSISTENCIES

You will have to split dialogue tracks in preparation for the mix. Because different camera positions occasion different mike positioning, a sequence's dialogue tracks played as is will change in level and room acoustics from shot to shot. The result is ragged and distracting when you need quite the contrary effect—the seamless continuity familiar from feature films. This result is achieved by painstaking and labor-intensive sound editing work in the following order:

- Split dialogue tracks (lay them by grouping on separate tracks) according to the needs imposed by the coverage's mike positioning.

a. In a scene shot from two angles and having two mike positions, all the close-shot sound goes on one track, and all the medium-shot sound goes on the other. With four or five mike positions, you would need to lay at least four or five tracks.

b. Sometimes tracks must additionally be split by character, especially if one of them is under- or over-modulated in the recording.

- Equalization (EQ) settings can be roughly determined during track laying, but final settings must be determined in the mix. The aim is to bring all tracks into acceptable compatibility, given that the viewer can expect a different sound perspective to match the different camera distances. These settings may now apply to multiple sound sections as they have been grouped according to EQ needs.

- Give special attention to cleaning up background tracks of extraneous noises, creaks, mike handling sounds—anything that doesn't overlap dialogue and can therefore be removed. Any gaps will sound like drop out unless filled with the correct room tone.

- If you have to join dissimilar room tones, do it as a quick dissolve behind a commanding foreground sound so the audience's attention is distracted from the change. The worst place to make an illogical sound change is in the clear.

Although manual and nonlinear sound mixing can handle many tracks, it is usual to premix groups of tracks and leave final control of the most important to the last stage.

Inconsistent Backgrounds: The ragged, truncated background is the badge of the poorly edited film in which inadequate technique steals attention from the film's content. Frequently, when you cut between two speakers in the same location, the background of each is different either in level or quality because the mike was angled differently or background traffic or other activities had changed over time. Now is the time to use those presence tracks you shot on location so you can add to and augment the lighter track to match its heavier counterpart. If an intrusive background sound, such as a high-pitched band saw, occupies a narrow band of frequency, you can sometimes effectively lower it using a graphic equalizer. This lets you tune out the offending frequency. But with it goes all sounds in that band, including that part of your character's voices.

Inconsistent Voice Qualities: A variety of location acoustical environments, different mikes, and different mike working distances all play havoc with the consistency of location voice recordings. Intelligent adjusting with sound equalization (EQ) at the mix stage can massively decrease the sense of strain and irritation arising from having to make constant adjustment to unmotivated and therefore irrational changes.

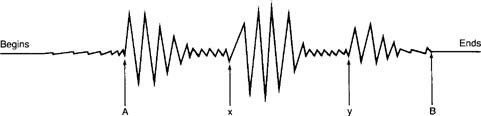

LAYING MUSIC TRACKS

It is not difficult to lay music, but remember to cut in just before the first sound attack so its arrival isn't heralded by studio atmosphere or record surface hiss prior to the first chords. Arrow A in Figure 43-1 represents the ideal cut-in point; to its left is unwanted presence or hiss. To the right of A are three attacks in succession leading to a decay to silence at arrow B. A similar attack-sustain-decay profile is found for many sound effects (footsteps, for instance) so you can often use the same editing strategy. By removing sound between x and y, we could reduce three footfalls here to two.

SPOT SOUND EFFECTS

These sync to something onscreen, like a door closing, a coin placed on a table, or a phone being picked up. They need to be appropriate, in the right perspective, and carefully synchronized. Sound effects, especially tape library or disk effects, often bring problematic backgrounds of their own. You can reduce this by cutting into the effect immediately before a sound's attack (see Figure 43-1, arrow A) and immediately after its decay (arrow B), thus minimizing the

FIGURE 43-1

Sound modulations: attack, three bursts, and decay. Arrows x and y indicate the best cutting points.

unwanted background's intrusiveness. Mask unwanted sound changes by placing them behind another sound. An unavoidable atmosphere change could be masked by a doorbell ringing, for example. You can bring an alien background unobtrusively in and out by fading it up and down rather than letting it thump in and out as cuts.

Bear in mind that the ear registers a sound cut in or a cut out much more acutely than a graduated change.

ATMOSPHERES AND BACKGROUND SOUND

Atmospheres are laid either to create a mood (birdsong over a morning shot of a wood or wood saw effects over the exterior of a carpenter's shop) or to mask inconsistencies by using something relevant but distracting. Always obey screen logic by laying atmospheres to cover the entire sequence, not just a part of it. Remember that if a door opens, the exterior atmosphere (children's playground, for instance) will rise for the duration that the door is open. If you want to create a sound dissolve, remember to lay the requisite amounts to allow for the necessary overlap and listen for any inequities in each overlap, such as the recordist quietly calling “Cut.”

TRADITIONAL MIX CHART

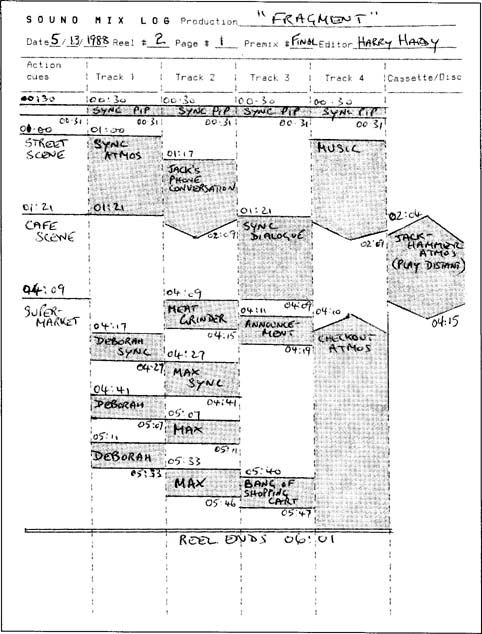

For traditional film mixes, you will need to fill in a mix chart blank (Figure 43-2), which reads from top to bottom, unlike a computer timeline, which reads horizontally from left to right. In the completed sample (Figure 43-3), each column represents an individual track. By reading down the chart you see that:

- Individual tracks play against each other, like instruments in a vertically organized music score.

- The sync pip or “BEEP” at 00:30 is a single frame of tone on all tracks to serve as an aural sync check when the tracks begin running.

- Segment starts and finishes may be marked with footages or cumulative timings.

- A straight line at the start or finish represents a sound cut (as at 04:09 and 04:27).

- An opening chevron represents a fade in (Track 4 at 04:10).

- A closing chevron represents a fade out (Track 2 at 02:09).

- Timings at fades refer to the beginning of a fade in or the end of a fade out.

- A dissolve is two overlapping chevrons (as at 02:04 to 02:09). There is a fade out on Track 4 overlapping a fade in for the cassette machine. This is called a cross fade or sound dissolve.

- Timings indicate length of cross fade (sound dissolve), ours being a 5-second cross fade.

- It is always prudent to lay both tracks longer in case you decide during the mix session that you would like a longer dissolve.

- You can lay up alternative approaches to a sound treatment, then choose the most successful by audition during the mix.

Vertical space on the mix chart is seldom a linear representation of time. You might have 7 minutes of talk with a very simple chart, then 30 seconds of railroad station montage with a profusion of individual tracks for each shot. To avoid unwieldy or overcrowded mix charts, use no more vertical space than is necessary for clarity to the eye. To help the sound mix engineer, who works under great pressure in the half-dark, shade the track boxes with a highlight marker.

SOUND MIX STRATEGY

PREMIXING

One reel of a feature film may comprise 40 or more sound tracks. Because only one to four sound engineers operate a traditional mix board, it requires a sequence of premixes, and the same principle holds for computerized mixes. It is vital to premix in an order that reserves until last your control over the most important elements. If you were to premix dialogue and effects right away, a subsequent addition of more effects or music would uncontrollably augment and compete with the dialogue. Because intelligibility depends on audible dialogue, you must retain control over the dialogue-to-background level until the very last stage of mixing. This is particularly true for location sound, which is often near the margin of intelligibility to start with.

Note that each generation of analog (as opposed to digital) sound transfer introduces additional noise (system hiss). This is most audible in quiet tracks such as a slow speaking voice in a silent room or a very spare music track. Analog video sound is the worst offender because sound on VHS cassettes is in narrow tracks recorded at low tape speed, which is the worst of all worlds. The order of premixes may thus be influenced by which tracks should most be protected from repeated re-transfer. Happily, digital sound copies virtually without degradation.

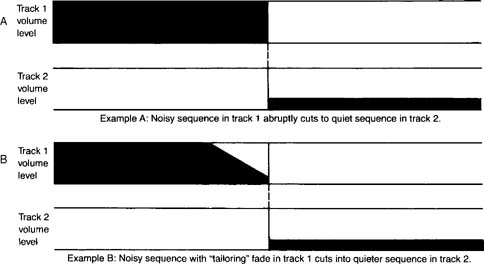

TAILORING

Many tracks, if played as laid, will enter and exit abruptly, giving an unpleasantly jagged impression to the listener's ear. This negatively affects how people respond to your subject matter, so it is important to achieve a seamless effect whenever you are not deliberately disrupting attention. The trouble comes when you cut from a quiet to a noisy track, or vice versa, and this can be greatly minimized by tailoring—that is, making a very quick fade-up or fade-down of the noisy track to meet the quiet track on its own terms. The effect onscreen is still that of a cut, but one that no longer assaults the ear (Figure 43-4).

FIGURE 43-4

Abrupt sound cut tailored by quick fade of outgoing track so it matches level of the incoming track.

COMPARATIVE LEVELS: ERR ON THE SIDE OF CAUTION

Mix studios sport excellent and expensive speakers. Especially for video work, the results can be misleading because low-budget filmmakers must expect their work to be seen on domestic TV sets, which have miserably small, cheap speakers. Not only do luckless consumers lose frequency and dynamic ranges, they lose the dynamic separation between loud and soft, so foregrounds nicely separated in the mix studio become swamped by backgrounds. If you are mixing a dialogue scene with a traffic background atmosphere, err on the conservative side and make a deliberately high separation, keeping traffic low and voices high. A mix suite will obligingly play your track through a TV set so you can be reassured of what the home viewer will actually hear.

REHEARSE, THEN RECORD

If you mix in a studio, you, as the director, approve each stage of the mix. This does not mean you have to know how to do things, only that you and your editor have ideas about how each sequence should sound. To your requests, and according to what the editor has laid in the sound tracks, the mix engineer will offer alternatives from which to choose. Mixing is best accomplished by familiarizing yourself with the problems of one short section at a time and building sequence by sequence from convenient stopping points. At the end, it is very important to listen to the whole mix without stopping, as the audience will do. Usually your time will be rewarded by finding an anomaly or two.

FILM MIXES AND TV TRANSMISSION

The film medium is sprocketed (has sprocket holes to ensure synchronization) so tracks or a premix are easily synced up to a start mark in the picture reel leader. The final mix, whether it is made traditionally or digitally, will be transferred by a film laboratory to a sprocketed optical (that is, photographic) track and then photographically combined with the picture to produce a composite projection print. Television used to transmit films from double-system; that is, picture and the magnetic mix were loaded on a telecine machine with separate but interlocked sound. The track was taken from the high-quality magnetic original instead of from the much lower-quality photographic track. Today television transmission is from the highest quality digital tape cassettes, which are simpler, easier, and more reliable in use.

MAKE SAFETY COPIES AND STORE THEM IN DIFFERENT LOCATIONS

Because a sound mix requires a long and painstaking process, it is professional practice to immediately make safety or backup copies. These are stored safely in multiple buildings in case of loss or theft. Copies are usually made from the master mix so that should its damage or loss occur, there are backups.

The same principle should be followed for film picture or video original cassettes; keep masters, safety copies, negatives, and internegatives (copy negatives) in different places so you don't lose everything should fire, flood, revolution, or act of God destroy what you might otherwise keep under your bed.

MUSIC AND EFFECTS TRACKS

If there is the remotest chance that your film will make international sales, you will need to make a music and effects mix, often referred to as an M & E track. This is so a foreign language crew can dub the speakers and mix the new voices in with the atmosphere, effects, and music tracks.