We’re all equal before a wave.

—Laird Hamilton, professional surfer

In 2005, I was working as an equity analyst at Merrill Lynch. When one afternoon I told a close friend that I was going to leave Wall Street, she was dumbfounded. “Are you sure you know what you’re doing?” she asked me. This was her polite, euphemistic way of wondering if I’d lost my mind.

My job was to issue buy or sell recommendations on corporate stocks—and I was at the top of my game. I had just returned from Mexico City for an investor day at America Movíl, now the fourth largest wireless operator in the world. As I sat in the audience with hundreds of others, Carlos Slim, the controlling shareholder and one of the world’s richest men, quoted my research, referring to me as “La Whitney.” I had large financial institutions like Fidelity Investments asking for my financial models, and when I upgraded or downgraded a stock, the stock price would frequently move several percentage points.

I was at the pinnacle of my Wall Street career, but getting to this place of power and respect had been hard won. My husband and I had moved to New York in 1989 so that he could pursue a PhD in molecular biology at Columbia University. While he was in school, we needed to pay our bills. I had to get a job. I’d majored in music (piano). I had no business credentials, connections, or confidence, so I started as a secretary to a retail sales broker at Smith Barney in midtown Manhattan. It was the era of Liar’s Poker, Bonfire of the Vanities, and Working Girl. Working on Wall Street was exciting. I started taking business courses at night and I had a boss who believed in me, which allowed me to bridge from secretary to investment banker. This rarely happens. Later I became an equity research analyst and subsequently cofounded the investment firm Rose Park Advisors with Clayton Christensen, a professor at Harvard Business School.

When I walked onto Wall Street through the secretarial side door, and then walked off Wall Street to become an entrepreneur, I was a disruptor. “Disruptive innovation” is a term coined by Christensen to describe an innovation at the low end of the market that eventually upends an industry. In my case, I had started at the bottom and climbed to the top—now I wanted to upend my own career. No wonder my friend thought I’d lost my sanity.

According to Christensen’s theory, disruptors secure their initial foothold at the low end of the market, offering inferior, low-margin products. At first, the disruptor’s position is weak. For example, when Toyota entered the U.S. market in the 1950s, it introduced the Corona, a small, cheap, no-frills car that appealed to first-time car buyers on a tight budget.

No one was worried about an upstart Japanese car manufacturer taking over a huge chunk of the American automobile market. In the theory of disruption, the market leader could have squashed this fledgling disruptor like a bug. But market leaders rarely bother. It’s a silly little product that would add nothing to the bottom line. Let’s focus on bigger, faster, and better. Early on, it didn’t make sense for GM to defend against the Toyota Corona. The problem is that once a disruptor gains its footing, it too will be motivated to move upmarket, producing higher-quality, higher-margin products.1 By the time a counterattack did make sense to GM, it was already too late. Toyota then moved happily upmarket with cars like the Camry and then the Lexus, eventually ceding the low end to Korea’s Hyundai. Now, waiting in the low-end wings are India’s Tata and China’s Chery.

From Wall Street’s perspective, these disruptors are the companies and people you want to invest in early on because their potential for growth is huge. Don’t we all wish we had invested in Toyota back in the 70s?

But it’s so easy to miss low-end disruptors.

I first started covering America Movíl, the Mexican telecom company, in 2002, building a financial model to determine whether the stock was over- or undervalued. To do this, I needed to predict how quickly wireless telephone adoption in Mexico would occur. In 2002, 25 percent of the Mexican population had adopted wireless, up from 1 percent just five years earlier, while standard landline penetration was about 15 percent. I now had to decide how much more wireless could grow. In analyzing who could afford a phone and who had access to credit, I thought wireless penetration could potentially reach 40 percent—or forty million people—by 2007.

Enter Carlos Slim, controlling shareholder of America Movíl. He saw a much bigger opportunity. In addition to the forty million people I saw, he saw the other sixty million people in Mexico who wanted to communicate but couldn’t afford to. So what did Slim do? He offered subsidized handsets and prepaid cards, making credit a nonissue. Sound quality was poor, but bad sound was better than no sound. Over the next decade, landline penetration increased a paltry five percentage points, from 15 percent to 20 percent, while wireless penetration roared past my projection of 40 percent to 90 percent. And in the pursuit of profit, the technology got better. That’s disruption.

When I first heard Clayton Christensen speak about disruption at an industry event, I recognized immediately that his theory explained why mobile penetration was repeatedly beating my estimates. Part of the reason disruption can be so hard to spot is the timing; the growth curve can look totally flat for years, then spike upward very steeply. In Mexico, wireless became available in 1988. For almost a decade, penetration was less than 1 percent, but in the five years between 1997 and 2002, penetration ramped to 25 percent.

As the pace of disruptive innovation quickens and you are in the midst of a crashing wave, what is unsettling can also be an amazing ride. This book isn’t about simply coping with the force of disruption, but harnessing its power and unpredictability, learning to ride its waves, and to disrupt yourself.

You may be trying something new, like leaving an established career to become an entrepreneur, as I did when I left Wall Street. You may be changing jobs within your current industry or company, or jumping to an entirely new field. As you’ll learn in the chapters that follow, disrupting yourself is critical to avoiding stagnation, being overtaken by low-end entrants (i.e., younger, smarter, faster workers), and fast-tracking your personal and career growth.

Understanding the S-Curve

Our view of the world is powered by personal algorithms. We observe how all of the components of our personal social system interact, looking for patterns to predict what will happen next. When systems behave linearly and react immediately, we tend to be fairly accurate with our forecasts. This is why toddlers love discovering light switches: cause and effect are immediate. But our predictive power plummets when there is a time delay or a nonlinear progression.

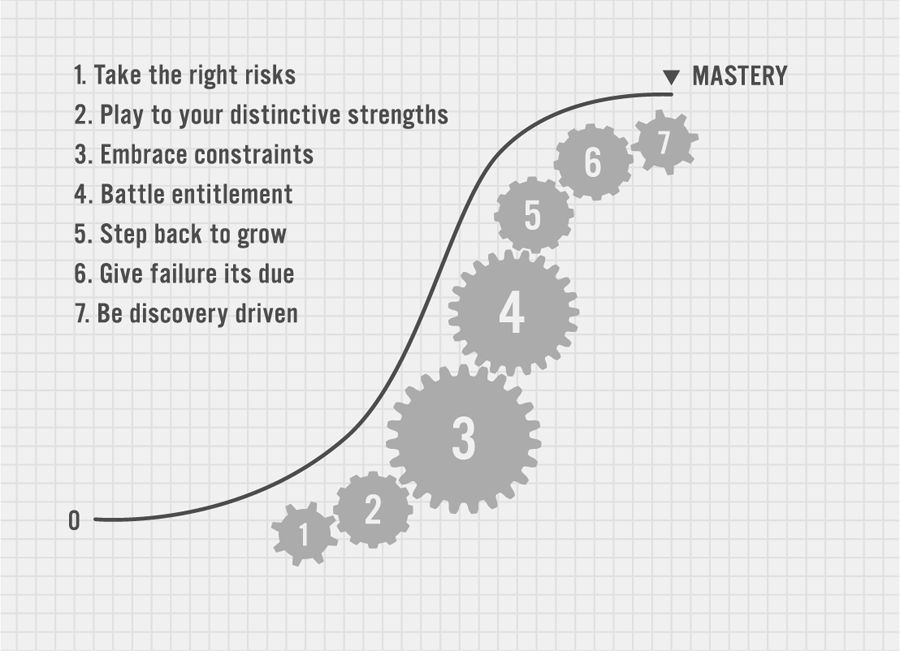

One of the best models for making sense of a nonlinear world is the S-curve. This model has historically been used to understand how disruptive innovations take hold—why a growth curve will stay flat for so long and then rocket upward suddenly, only to eventually plateau again. Developed by E.M. Rogers in 1962, the S-curve model is an attempt to understand how, why, and at what rate ideas and products spread throughout cultures. Adoption is relatively slow at first, at the base of the S, until a tipping point, or knee of the curve, is reached. You then move into hypergrowth, up the sleek, steep back of the curve. This is usually at somewhere between 10 to 15 percent of market penetration. At the flat part at the top of the S, you’ve reached saturation, typically at 90 percent.

FIGURE 1-1

Facebook, for example, based on a market opportunity of one billion users, took roughly four years to reach penetration of 10 percent. But once Facebook reached a critical mass of a hundred million users, rapid growth ensued due to the network effect (i.e., friends and family were now on Facebook), as well as virality (e-mail updates, photo albums for friends of friends, etc.); over the next four years, Facebook added not one hundred million but eight hundred million users.2

I believe the S-curve can also be used to understand personal disruption—the necessary pivots in our own career paths. In complex systems like a business or a brain, cause and effect may not always be as clear as the relationship between the light switch and the light-bulb. There are time-delayed and time-dependent relationships in which huge effort may yield little in the near term, or in which high output today may be the result of actions taken a long time ago. The S-curve decodes these patterns, providing signposts along a path that, while frequently trodden, is not always obvious. If you can successfully navigate, even harness, the successive cycles of learning and mastering that resemble the S-curve model, you will see and seize opportunities in an era of accelerating disruption.

Self-disruption will force you up steep foothills of new information, relationships, and systems. The looming mountain may seem insurmountable, but the S-curve helps us understand that if we keep working at it, we can reach that inflection point where our understanding and competence will suddenly shoot upward. This is the fun part of disruption, rapidly scaling to new heights of success and achievement. Eventually, you will plateau and your growth will taper off. Then it’s time to look for new ways to disrupt.

One story that shows how the S-curve model can help us better forecast the future is the experience of golfer Dan McLaughlin. Never having played eighteen holes of golf, McLaughlin quit his job as a commercial photographer in April 2010 to pursue a goal of becoming a top professional golfer through ten thousand hours of deliberate practice. During the first eighteen months, improvement was slow as McLaughlin practiced his putting, chipping, and drive. Then, as he began to put the various pieces together, he moved into a phase of dizzying growth. Within five years, he had surpassed 96 percent of the twenty-six million golfers who register a handicap with the US Golf Association (USGA). Though McLaughlin was keen to move from the top 4 percent to the top 1 percent of amateur golfers, as he achieved mastery, S-curve math predicted his rate of improvement would decline more and more sharply over time.

The Psychology of Disruption

The S-curve also helps us understand the psychology of disrupting ourselves. As we launch into something new, understanding that progress may at first be almost imperceptible helps keep discouragement at bay. It also helps us recognize why the steep part of the learning curve is so fun. When you are learning, you are feeling the effects of dopamine, a neurotransmitter in your brain that makes you feel good. It’s an office dweller’s version of thrill seeking. Once we reach the upper flat portion of the S-curve and things become habitual or automatic, our brains create less of these feel-good chemicals and boredom can kick in, making an emotional case for personal disruption. At a career peak, there is certainly the specter of competition from below, but just as importantly, there’s the risk that if we aren’t on a curve that satisfies us emotionally, we may be the cause of our own undoing. When we are no longer getting an emotional reward from our career, we may actually end up doing our job poorly.

With learning, our progress doesn’t follow a straight line. It is exponential and expands by multiples. Instead of learning a fixed number of facts and figures each day, what we learn is proportional to what we’ve already learned. We needn’t merely plod along, moving one up and one over on the graph paper of existence. If we apply the right variables, we can explode into our own mastery.

FIGURE 1–2

I’ve identified seven variables that can speed up or slow down the movement of individuals or organizations along the curve, including:

Taking the right risks

Playing to your distinctive strengths

Embracing constraints

Battling entitlement

Stepping back to grow

Giving failure its due

Being discovery driven

FIGURE 1–3

We’ll devote a chapter to each.

This book is about surfing the S-curves of your own personal disruption. Yes, disruption can feel a bit scary, but the payoff of career growth and personal achievement makes overcoming the fear factor well worth it. We all start at the low end of the learning curve. This book will teach you how to shift into hypergrowth and, when your learning crests, to do what great disruptors do: catch a new wave.