“If we do not change our direction, we are likely to end up where we are headed.” | ||

| --CHINESE PROVERB | ||

IMAGINE FOR A MOMENT that you’re just over 20 years old. You know exactly what you want to do with your life: you’ve found your passion. You’re proudly paying your own bills doing what you love. Life is good.

I first discovered my passion publishing a magazine in high school. At University of Waterloo, it was all-nighters at the student paper, neglecting my degree program in computer science. By the late 1980s, I had followed my muse to a tiny design studio above a pawnshop in old Ottawa South. Like so many other young people who realize that designing is who they are, I was jazzed with creating, exploring, and pushing the limits of my perfect little world-within-a-world of grids, fonts, and Pantone® colors, long before desktop publishing would make such terms household words.

In front of David Berman Typographics, Hopewell Avenue, 1988

I could shut out the messy world and strive to surround myself with beautifully designed things. There was delight in staying up all night spinning two-inch font filmstrips through my Typositor, hand-rolling adhesive wax onto phototype galleys, refining kerning pairs, and unavoidably breathing photo chemicals. X-Acto blades, Letraset, and Rubylith... in the morning, I would zoom around town with a huge portfolio case strapped to my bright-red scooter, wearing cotton crayon shoes and all-black everything else.

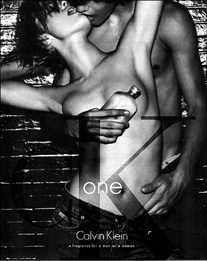

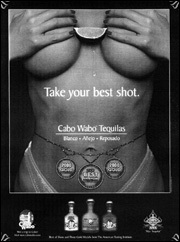

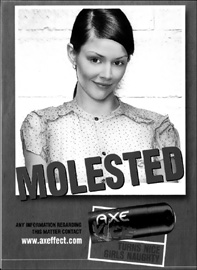

So when that hot[6] feminist girlfriend tore into my microcosm, claiming that graphic designers like me were responsible for destroying forests in support of the systematic objectification of women by using pictures of their bodies to help sell products... well, my first reaction was to deny everything. But then I took notice of example after example, and promised to do something about it.

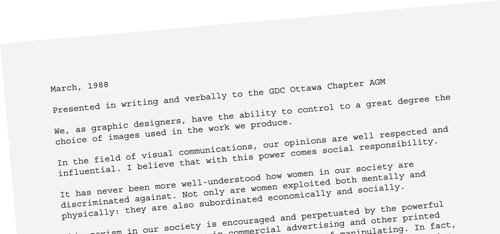

A youthful, creative, male mix of social justice, lust, and angry young hubris naively scooted me off to my first-ever meeting of the local chapter of the Society of Graphic Designers of Canada. Hastily written eco-feminist manifesto clutched in my hand, I was intent on changing the code of ethics of my profession. Little did I know that ride would span 16 years and take me to more than 20 countries and counting, vastly exceeding my naïve expectations. But more on that later...

Fast-forward 12 years, to the turn of the millennium, when it dawned on me that designers not only had the potential to be socially responsible, but also may actually hold the future of the world in their hands. Here’s an example.

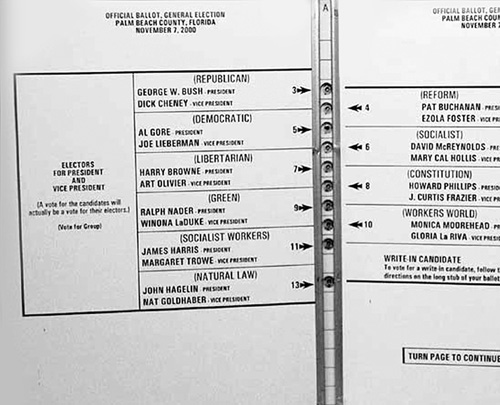

The most influential piece of information design in my lifetime may very well be the butterfly ballot used in Palm Beach County for the November 2000 U.S. presidential election. The number of votes mistakenly cast for independent Pat Buchanan instead of Al Gore, due to the misleading layout, was well in excess of George W. Bush’s certified margin of victory in Florida, and enough to result in Bush winning the presidency nationally. The poor design of this ballot is therefore likely responsible for the failure of the United States to sign the Kyoto Accord on climate change, the 2003 invasion of Iraq in search of weapons of mass destruction,[7] and a long list of controversial White House decisions during the eight years that followed.

AIGA’s Design for Democracy is currently working with the U.S. government to clean up the ballot mess, which has compromised the mechanics of democracy.[8] As a result of its efforts, in June 2007, the U.S. Election Assistance Commission issued voluntary guidelines for the effective use of design in administering federal elections. However, in the 2008 election, its recommendations were only reflected in the ballot design of perhaps six states. The United States continues to have thousands of different ballot designs, with varied technologies, for electing one president.[10]

“It’s very easy for me to see how someone could have voted for me in the belief they voted for Al Gore.” | ||

| --PAT BUCHANAN[9] | ||

Responsible government should provide voters with a consistent ballot, designed by information design experts. In Canada, as in most Western democracies (let alone in countries like Afghanistan and Iraq, which ironically provide their citizens clearer ballots that the U.S. does), anything other than a professional and consistent national ballot design would be an affront. It is oddly inconsistent that, by law, the United States Food and Drug Administration requires consistent nutrition facts on every one of thousands of food package designs, while the U.S. government fails to legislate the use of a consistent, well-designed ballot and voting procedures across its 51 states and districts.

South Africa got it right the first time, in their 1994 election. The vast majority had not voted before, with a substantial portion illiterate. A simple ballot including candidate photos worked well. The influence of design on election outcomes does not stop at the ballot box. Candidates spend most of their war chests on ads. Many of these messages are oversimplified and intentionally misleading, cunningly combining pictures and words out of context. Advertising Age columnist Bob Garfield admits “Political advertising is a stain on our democracy. It’s the artful assembling of nominal facts into hideous, outrageous lies.”[11] In 2004, U.S. presidential candidates spent over a billion dollars[12] disingenuously manipulating opinions, rather than simply presenting straightforward information that helps voters make an intelligent choice. President Obama was the third-largest advertiser in the country during the 2008 campaign,[13] including an unprecedented online effort focused on positive messages.

Palm Beach County ballot, Florida, 2000: even Pat Buchanan was shocked at his proportion of the Jewish and black vote. With many pages of voting ( 11 offices, 9 judicial contests, and 4 referenda) to complete, many voters wrongly marked the second hole from the top to indicate their “Democratic” intention.

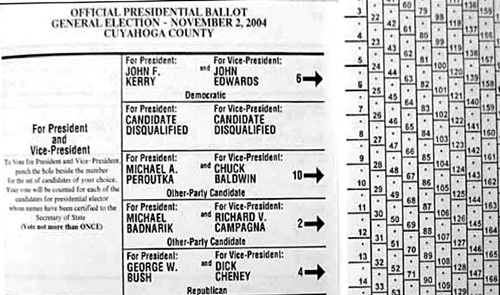

Not the solution: it was just as difficult to vote for George W. Bush for president in Ohio in 2004.[14] Voting for Kerry was easy: mark box 6. But how do you vote for President Bush?

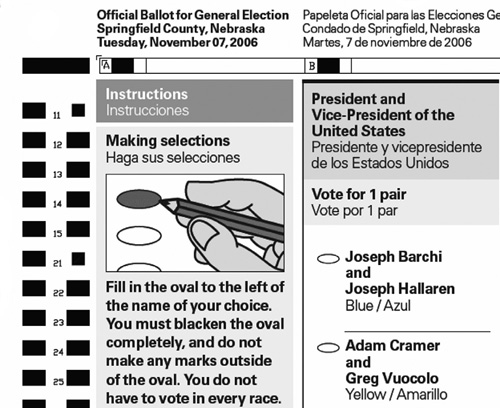

One of many sample ballots created by AIGA’s Design For Democracy for the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. Their recommendations were reflected in ballot design used for the November 2008 presidential election within at least 6 states.

How have these manipulations become the norm? If the American public is to be equipped to choose the best leaders, we either need mandatory media literacy education starting in elementary school, or legislation that prohibits lying with imagery as strongly as current legislation prohibits lying with words. Meanwhile, good design can encourage youth to seize the cynical 54 percent U.S. election turnout rate as an opportunity.[15]

That same chad-hanging election year, my daughter Hannah and I were on the way to her school. She was eight (and a half!) years old. As we passed by a beautiful bill-board that proclaimed “Drink Milk. Love Life,” Hannah, who does not like drinking cow’s milk, had questions.

HANNAH: “David, I don’t drink that milk. Does that mean I can’t love life?” [Yes, she’s always called me David.]

DAVID: “No, of course not.”

HANNAH: “Do I love life less than kids who drink a lot of milk?”

DAVID: “No, Hannah, they just made that up to try to convince you to drink more milk.”

HANNAH (after a long pause): “Why are they allowed to say that if it isn’t true?”

“We do not inherit this land from our ancestors, we borrow it from our children.” | ||

| --HAIDA PROVERB | ||

Good question, Hannah. At the time, I was preparing to speak at a design conference in Vancouver. Like most designers, I had planned to show my best work. But in that moment with my daughter, an idea hit me: instead of speaking about my own design work, why not instead speak about the influence of all design work?

What could become possible if designers used their power to influence choices and beliefs in a positive and sustainable way? Imagine: what if we didn’t just do good design... we did good?

Many conferences, keynotes, and seminars later, I’m still traveling with that message. On the way, I’ve learned as much as I’ve taught, often from those who are younger.

I met a young boy in rural Tanzania. He was clutching a plastic bag, decorated with the Camel cigarette brand, the only camel he is likely to meet in his lifetime.

Tengeru, Tanzania

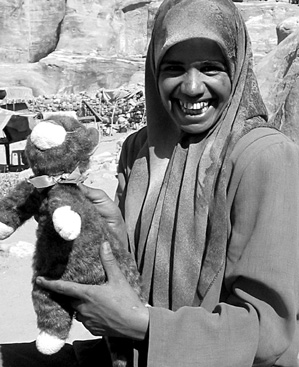

In 2002, I spoke at a design conference in Amman, Jordan. We took a day trip to Petra – an ancient city majestically carved entirely from the surface of rock, and certainly the eighth wonder of the world. There I met a young woman and her camel. They live in the nearby town of Wadi Musa, where the largest sign in the town proclaims the “Superior American Taste” of a local cigarette brand.

Bedouin friend, Petra, Jordan. (The cat is my traveling companion, Spice, one half of twins: Blackie stays home with my daughter)

Wadi Musa, Jordan

On the flip side of my world, back home in Canada, my daughter has never seen a cigarette billboard: all tobacco advertising likely to be viewed by children is illegal in Canada.[16]

The cigarette: highly effective British industrial design from the 1880s

Cigarettes are among the most highly advertised products in the world. Big Tobacco will spend over $13 billion this year[17] promoting their cleverly designed disposable nicotine-delivery system. Their goal: to convince all three of these youth to start smoking cigarettes, within their teenage years, until they die. [All $ in the book are U.S. dollars.]

In proudly free Western societies, we like to tell parents that it’s up to them to control what their kids see and don’t see. It is said that it takes a village to raise a child. I would add that it takes a society to raise a generation. Striving to be a good parent, I will help my daughter make clever choices around tobacco, and hope that she will live a long and healthy life, perhaps well into the next century.

When that 22nd century arrives, and our children’s grandchildren look back on these remarkable days in which we lived, what will history recall as our most crucial issue?

My daughter, Hannah

The potential impact of any global threat to humanity is far greater when combined with the current trend toward homogeneity of civilization design. Let me explain.

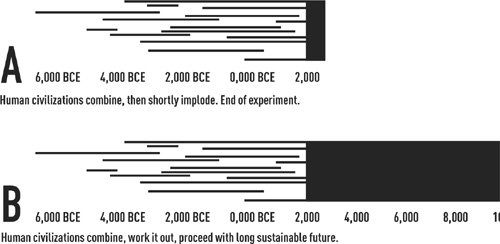

Human civilizations have come and gone, risen and fallen. Although most scientists believe our species has been around for at least five million years, this approach to social organization is only around 6,000 years old (10,000 at most).[18] However, as science philosopher Ronald Wright points out, after 6,000 years of experimenting with civilization design, we humans now find ourselves sailing together into the future on the one huge remaining ship of a combined global civilization.[19] Whether or not we welcome or like the idea of globalization, we are witnessing in our lifetimes our evolution into a singular, merged human community – the largest ever. There are no more geographic New Worlds to discover: only a shared destiny.

Wright goes on to describe civilization as God having let loose a special group of primates – the human animal – into the laboratory of life, giving them the power to tinker with life itself. What scares me the most about this image is that we are all now living inside the experiment: if we accidentally destroy “the lab,” we have no home left, either for ourselves or our future generations.

For good or for bad, our globalized inventiveness is fusing our destinies into one civilization. So together, humanity must choose wisely, and in this lifetime. Our common future is our common design challenge.

With or without us, evolution moves forward by trial and error. But if the future is to include a recognizable human civilization, we cannot absorb one more major miscue.

I hope that, 100,000 years from now, our descendants will look back on those first 6,000 “childhood” years of the Big Bang of civilization as the successful adolescence of humanity: that awkward time when there were many civilizations would be a distant memory. Maybe we will be remembered for somehow overcoming our adolescent delusions of immortality and inane infighting, bringing forward the best of all cultures, and designing a sustainable future together: that we found a way to meet our needs without compromising the ease for future generations to meet theirs.

Wright’s ship analogy describes our situation well. Consider that many miles of open sea are needed to turn a huge ship around: In the event that an iceberg appears on our horizon, we must start changing direction far in advance, to avoid crashing into it. If we wait too long, we pass the event horizon, with no choice but to resign ourselves to witnessing our demise in painfully slow motion. Design has the potential to help steer us to a safer course.

“As Homo sapiens’ entry in any intergalactic design competition, industrial civilization would be tossed out at the qualifying round.” | ||

| --DAVID ORR[21] | ||

Which future should we choose?

So which iceberg threatens us the most?

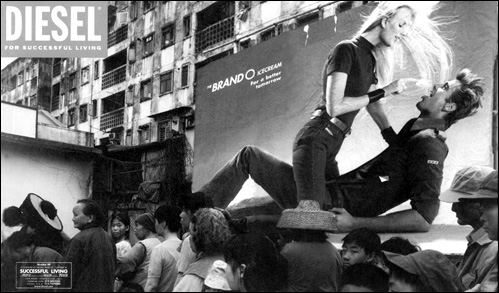

Italy’s Diesel brand presents a bizarre juxtaposition of Asian poverty and American poverty

Is it terrorism? I don’t think so. Though timely and freshly horrible in our minds, terrorism is not a new phenomenon and has yet to pose a serious threat to civilization. (I do think it is worth pondering why intelligent, and not particularly radical, people from around the world are increasingly angry at and offended by Western culture. Perhaps they are outraged about being lied to continually by the most sophisticated deception process in history. More on this later.)

Perhaps the iceberg is a pandemic. A global pandemic is a highly probable catastrophe that deserves attention, including well-designed messaging to mitigate its effects. The spread of infectious disease is not new. In today’s world, infectious diseases spread farther and faster than before, due to international travel and shipping. The likelihood of a global pandemic of deadly, drug-resistant influenza or tuberculosis grows every day. Health authorities tell us that the question is not if, but when. Nonetheless, the worst scenario, while devastating, wouldn’t likely end civilization as we know it.

Is the iceberg financial collapse? Or corruption? We’ll consider design’s role in these ills in the next chapter; however, we have overcome this type of challenge in the past and we will again.

No, the answer is “none of the above.” When our children’s children look back at the biggest issue of our era, they will see the most deadly threat as the devastation we wrought on our physical environment.

It is unfortunate that the culture that was the most influential of the 20th century also happens to be perhaps the world’s most environmentally unsustainable.

“There are no passengers on Spaceship Earth. We are all crew.” | ||

| --HERBERT “MARSHALL” MCLUHAN (1911–1980)[22] | ||