There are so many people who have dreamed seemingly unattainable dreams and, because they never gave up, achieved their goals against all odds.

—DR. JANE GOODALL

4

The “No-Willpower” Myth

In a series of educational cartoons created by the U.S. Navy in the 1950s, the comic bunglings of an incompetent mechanic named Murphy were used to make various learning points. This is the fictitious Murphy after whom Murphy’s Law is named. Most people can recite at least the first part of Murphy’s Law without hesitation: “If something can go wrong, it will—and even if it can’t, it still might.” The principle is known as “Sod’s Law” in Britain and is also sometimes referred to as Spode’s Law. It appears to have been inspired by an earlier mythical fourth general law of physics: “The cussedness of the universe tends to a maximum.”

74Something intriguing has happened to Murphy’s Law over the years. Whereas it began life as a joke, a make-believe law of nature to encourage people to avoid problems by anticipating all that might go wrong and taking appropriate preventive measures, it soon became a semivalid general principle to grumble about how the world as a whole sometimes seemed to operate. From there, it has gradually taken on the legitimacy of a “timeless truth” that describes how the world actually does operate. Murphy’s Law is the foundation of the pessimist’s entire worldview. For anyone seeking to make a big dream come true, this joke is no laughing matter.

Programmed for Self-Defeat

Have you ever heard anyone quote the opposite of Murphy’s Law, which states that “If something can go right, it will—and even if it can’t, it still might”? Neither have we. And yet something we have often heard is people describing happy occasions in their lives when “Everything went perfectly,” “Everything just somehow came together,” “Even the weather cooperated,” “It was amazing, it was as if it had all been planned,” and so on. Our culture has no “cute” law to refer to by name when that happens. So why not create one? Let’s call it the dreamcrafter’s law; any time you observe things going right for you or anyone else, point out that this is entirely in keeping with the dreamcrafter’s law, which states that “If something can go right, it will.” The usefulness of doing so lies in discovering that situations in which the dreamcrafter’s law applies will prove to be every bit as plentiful as those which seem to support Murphy’s view.

The Murphians treat it as a given: things are simply by nature more likely to go wrong than right. It’s a widely held view with what appears to be supporting evidence on all sides. And where does this evidence come from? Where do we, as individuals, get our big picture of how the world at large operates? For the lucky few, this understanding comes from direct personal experience—traveling widely, sampling different cultures with different values, discovering those elements that make various societies unique and those that make them alike. For most people, though, their grasp of how the world works comes from indirect sources, such as books, newspapers, and especially television. But—key question—is the picture that emerges from these indirect sources reliable?

75“Coming up on Eyewitness News—another peaceful and orderly evening in our city, everybody getting along just fine. No violence, no unpleasant incidents of any kind. Tom Kirkland has a full in-depth report at 11:00.” Is this news item going to attract the kind of audience the sponsors of the nightly newscasts are hoping for? People may believe they’re watching the news to learn what’s new in the world, but what’s really being served up is everything that’s wrong in the world. News at the breakfast table, news at the dinner table, news twenty-four hours a day, day in, day out, year in, year out, a steady diet of things gone wrong locally, nationally, and internationally. This would certainly make it easy for anyone to conclude that Murphy knew what he was talking about.

But even if bad news is more abundant than good news on the airwaves, does it follow that bad things are more likely to happen in the world than good things, as the Murphians claim?

Let’s talk basic mathematical probabilities for just a moment. Let’s say you’re flipping a coin and for some reason you start getting a string of “heads”—five in a row, nine in a row, fourteen in a row. People start gathering around to watch, amazed. How long can this lucky streak continue? You’ve just flipped heads for the nineteenth consecutive time. An eccentric rich guy watching you suddenly blurts, “If you get a twentieth head in a row, I’ll give you twenty thousand dollars.” Everyone applauds and moves in closer to watch what happens. It’s now up to you to get heads for the twentieth time; if you do, the money is yours. Question: how would you rate your chances of winning the money?

Give it a moment’s thought. What are the odds? Even if you said “fifty-fifty” without hesitation, can you appreciate how it wouldn’t feel like a fifty-fifty proposition? It would be hard to shake the feeling that with each successive heads, your chances of getting heads again somehow shrank. After nineteen of them, it feels as if the chances are very much stacked in favor of getting tails on the twentieth toss.

76But the odds would only be stacked against you if the rich guy had offered his prize for twenty consecutive heads before you’d done any flipping at all. The odds of getting five heads in a row are pretty poor; those for ten in a row are poorer yet, and the odds for twenty in a row are almost hopeless. But in this case the rich guy made his offer after you’d already beat the odds and flipped nineteen in a row. So, in effect, all he was saying was, “If you flip that coin once, right now, and it happens to come up heads, I’ll give you the money.” The coin doesn’t “know” about the nineteen heads earlier. You’ll flip it, and it will land on one side or the other, and that’s it—straight fifty-fifty odds.You’ve got a very good chance of winning the rich guy’s money.

Most of us don’t have a good feel for probabilities to begin with, a fact which gladdens the hearts of casino owners everywhere. But now suppose that in addition to this, we happen to have been born into a society in which we always saw depictions of coins coming up tails—morning, noon, and night, day in and day out, from childhood onward. Every day, the news was filled with stories about tails coming up locally, nationally, and right after this short word from Buster Burger, internationally. Suppose people around us were forever quoting a “law” that states, “If something can come up tails, it will.” Suppose the whole of society were virtually steeped in “taildom”? In a society such as this, anyone who would say, “It’s actually every bit as likely that a flipped coin will come up heads,” would probably be dismissed as a naïve, deluded Pollyanna, with no grasp of the gritty, unpleasant realities of life. In such a society, the basic sense of hope would have been virtually programmed out of existence.

The antidote for undesirable programming is reprogramming. We begin the reprogramming process when we remind ourselves, hour by hour if necessary, that the depiction of the world that’s reaching us every day is severely distorted, very heavily skewed toward a Murphian view. Keeping this consciously in mind helps immunize us against the contaminating effect such a view can otherwise have on our expectations. By all means watch the nightly news—but keep reminding yourself that this represents only a part (perhaps only a very small part) of what went on in the world today. Bear in mind that tranquility and harmony make for dull newscasts, even though they make for a good life. News at its best depicts life at its worst.

77The sense that the world is stacked against us is a typical product of Murphian contamination. The process of reprogramming begins immediately, and continues every hour of every day. Each new instance of something going right in your life, near you, or somewhere in the world at large—each new validation of the dreamcrafter’s law—adds more weight to help tip the balance against all the Murphian examples the media have been feeding you every day of your life.

Breaking the Failure Pattern

But even when we succeed in reassuring ourselves that the world is not stacked against us after all, there remains an even more damaging source of negative expectations that must be removed. We can come to see that our sense of how the world works is skewed, that the indirect sources of our view of the world are distorted and unreliable. But when it comes to our view of our own capabilities, this is the product of direct personal experience. We have seen firsthand how we tend to mess things up, how we tend to fail in our attempts to achieve ambitious objectives. All too often, it is we who are stacked against ourselves. How do we turn these negative expectations—based on an actual history of personal failure—into positive ones?

“Men at some time are masters of their fates,” says Cassius in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar; if we fail to achieve our goals, “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.” And first and foremost among the personal “faults” most people cite to account for their failure to achieve their goals is lack of willpower.

78Willpower—in the minds of many, it’s that precious commodity their heroes possess in such abundance, but which in the makeup of their own character always seems to be in such dishearteningly short supply. But this assumption is mistaken. It is not willpower that is lacking. If you automatically duck without even thinking about it any time you see something flying toward your head, your basic survival instinct—your will to live—is working just fine; it means you’ve got willpower galore wired in right at the genetic level. Even if you prefer to use the word in the narrowest dictionary sense, to mean nothing more than “determination,” most people still have it in abundance. Climbing out of a soft, warm bed day after day in order to toil away at a monotonous unfulfilling job, devoting hours of every day to the never-ending task of keeping the house clean and tidy, struggling with traffic jams, and with lines at the supermarket and at the bank, and driving kids hither and yon, and trying to balance the checkbook, and resisting the urge to tell the boss what we really think of him or her—now these are things that require real determination. Think back to those workplace placards and bumper stickers that read, “I’d Rather Be Sailing” or “I’d Rather Be Fishing.” Ours is a society in which a great many people by their own admission would nearly always rather be doing something else, someplace else. The whole social and economic fabric of our entire way of life depends on the vast majority of the population ignoring what they would “rather” be doing for the better part of their waking lives. This is willpower on a cosmic scale.

What most people are describing when they refer to their supposed lack of willpower is in reality a lack of skillpower—a poorly defined (and therefore uncompelling) mission, for example, coupled with an unclear (or even nonexistent) vision of success, and no provision whatsoever for sustaining motivation over the long term. No measurement system, no celebration strategy, no thought given to enlisting the support of others. Despite all their best intentions, without macroskill support theirs is a mission virtually wired to fail from the outset.

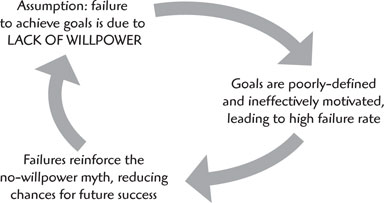

This is the classic failure pattern that plagues so many. If a given mission ends in failure, their automatic assumption is that it can only be attributable to an underdeveloped will to succeed on their part. “I obviously couldn’t have wanted it very badly,” they’ll wistfully explain with a shrug. “I just didn’t have the willpower to stick with it and see it through.” Thus unfolds the self-perpetuating cycle of failure in their lives, with each new failure reinforcing the negative expectation that all of their aspirations are likely to end the same way, and for the same reason. There’s just some tragic flaw within themselves that will forever prevent them from making their dreams come true.

79

Do you recall the day you first learned to tell time? Until someone let you in on the knowledge behind it, your every attempt to figure it out by staring intensely at the face of a clock ended in failure. This inability to tell time—without any understanding of the principles involved—did not represent some flaw in your character or personality. And until you master the principles and techniques for making dreams come true, your efforts to figure it out on your own may similarly not always be successful. This does not in any way represent some sort of character or personality flaw. Skill, knowledge, technique—even the most gifted pianist in the world has to sit down and practice the same scales and absorb the same theoretical principles as every tin-eared beginner. Just having the will to play the piano won’t be enough, no matter how great the talent or the desire. Skill is essential, and mistaking the absence of skill for an absence of will is a costly mistake that fuels the machinery of negative expectations.

80The “no willpower” myth reinforces pessimism, the killer of dreams.

Life Lessons Learned on Roller Coasters

When negative expectations intensify, they acquire new names: anxiety, dread, fear, panic. We describe their onset as an “attack.” The condition we refer to as “fear of flying,” for example, is a case of negative expectations that have assumed debilitating proportions. But whereas only a small proportion of the public suffers from a serious fear of flying, the somewhat similar fear of roller coasters is much more common—and can thus serve to help us grasp a principle with very useful dreamcrafting applications.

Some people love roller coasters, some people hate ‘em—but if we could hook up electrodes to the bodies of a typical carload of riders being drawn to the top of the first drop, we might find it difficult to distinguish between the lovers and the haters of coasters on the basis of these measurements alone. In terms of sweatiness of palm, palpitation of heart, quickness of breath, and so on, the readings from both groups might look much the same. Extremes of dread and of exhilaration can produce very similar physiological responses—the difference is very much in the mind of the beholder. So, too, with certain “upsetting” movies. During the great worldwide Titanic pandemic of ’98, millions sobbed through the movie, yet stood patiently in line to go back inside and experience all that sorrow, terror, and sense of loss all over again. Here, too, the physical experience seemed to be very negative, while the emotional aspect appeared predominantly positive.

Now let’s add a new wrinkle to these experiences. The entire staff of Roller Coaster Enthusiast magazine is being given a special press-only pre- view of the new Satan’s Wrath coaster. Right as the cars are swooping downward at terrifying speed, their riders screaming in joyous bloody terror, a large metal beam that had been holding a promotional banner over the summit of the next hill breaks loose and crashes down to the tracks, directly in the path of the speeding cars. The screams of the riders continue unchanged; park officials observing from the ground cannot see the fallen beam, and thus have no indication that for the riders the basic nature of their experience has suddenly undergone a profound change.

81Meanwhile, a group of honeymooning couples, selected precisely because they have never seen the film Titanic, has been invited to a very special screening aboard a replica of the original ship, making its maiden voyage on a cold wintry night. The honeymooners, caught up in the parallels between the onscreen love affair and their own recent romantic lives, are dabbing at their eyes when they feel the floor beneath them lurch suddenly. An explosion has occurred in the engine room, and the ship has begun to take on water at an alarming rate. The nature of their experience, too, has suddenly changed in a fundamental way.

But what is it, specifically, that has changed to so dramatically transform the emotional component of these experiences (while keeping the physiological aspects about the same)? In the simplest terms, it is the expectations of those involved that have changed. Even people who detest roller coasters will admit, if pressed, that they expect to come off the ride alive (even if their racing hearts don’t seem to share their optimism). When the beam crashes down, suddenly the magazine staff’s emotional expectations are more in sync with their physical ones; it suddenly looks as if maybe their bodies were right, maybe they are about to perish. The honeymooning filmgoers can feel for the onscreen characters in the icy water—but when it suddenly looks as if they could soon be immersed in frigid water in a vast open ocean themselves, their (positive) enjoyment of identifying with others in distress is replaced with the same (negative) disquiet their sobbing, anxious bodies had been manifesting all along.

Some people have clearly taught themselves to sublimate their physiological responses (anxiety) in order to take delight in the emotional responses (exhilaration, inspiration) that accompany certain kinds of experiences. Many consider public speaking a terrifying ordeal, but former Canadian prime minister and Nobel Peace Prize winner Lester B. Pearson once quipped, “It’s okay to have butterflies [in your stomach], as long as they’re flying in formation.” Hampered by a speech impediment, Pearson was personally terrified of speaking before groups of people—yet became president of the U.N. General Assembly. Toronto’s international airport, Canada’s largest, is named after him.

82This ability to get their butterflies flying in formation is what those who take up skydiving, bungee jumping, rock climbing, and so on, cultivate within themselves in order to sublimate their fears. It’s not that roller coaster devotees do not experience the physical sensations of fear. To the contrary, it’s that (drawing assurance from the knowledge that they’re actually perfectly safe) they allow themselves to enjoy these physical sensations. Thrill seekers of all stripes speak of an “adrenaline rush,” and describe themselves as adrenaline junkies. Far from harboring a death wish, these people yearn to experience being alive to the fullest. Their secret recipe: take fear, remove the negative-expectation component, and bingo, you’ve got exhilaration!

This is a vital recipe for prospective dreamcrafters. It summarizes a peculiar sensation that can sometimes arise when there is a temporary disparity between emotion and reason, between feeling and knowing. The lover of thrill rides in amusement parks enjoys the combination of feeling he or she is in considerable danger, while at the very same time knowing he or she is actually perfectly safe. (If the ride breaks down, the knowledge of safety disappears, and only the sense of danger is left— no more disparity, no more exhilaration.) It explains why those who undertake daring projects in their lives, who pursue ambitious dreams, tend to look and sound so darn happy most of the time. They know that what they’re doing is daring, or risky, or dangerous.Yet they too have removed their negative expectations (their fear of failure) by replacing them with positive ones (their ever increasing confidence that they will succeed). They are left with the same adrenaline rush and feeling of exhilaration. The very word thrill is often used to describe precisely this sensation of danger experienced while actually safe. People who have set out to make their Big Dream come true almost invariably refer to their quest as the most thrilling period in their lives. Dreamcrafting is thrilling business.

83Remove negative expectations from the sensation of fear, and what’s left is a feeling of exhilaration.

Yes, but how does one go about replacing negative expectations with positive ones? Is there an actual process for doing so?

Anticipating the Naysayers

I‘ve got a bad feeling about this,” movie and television characters sometimes intone portentously. Their premonition is usually linked to a very specific set of circumstances; but it’s a sentiment many pessimists can surely relate to. For them, a lifetime of collecting and reinforcing negative expectations will often produce one big simmering stewpot of apprehension into which all their fears and anxieties have been dumped. They spend much of their lives experiencing that vague “bad feeling” about how things are going to turn out.

The more formless and nonspecific this bad feeling is, the more overwhelming it can become. These are no longer individual concerns that can be addressed and disposed of one at a time; they’ve now become one big thick stewlike aggregation of negativism that’s been simmering for years. A sense of futility overpowers the sense of mission, and paralysis sets in.

You can’t unscramble a scrambled egg, as the saying goes. What about this stew of negative expectations—can it be “un-stewed”?

Call it playing devil’s advocate, call it wearing the black hat (from Edward de Bono’s Six Thinking Hats), or call it a way to arrive at optimism by first becoming pessimistic and working through every pessimistic projection one at a time. Whatever you call it, the “craft” in this instance involves anticipating what naysayers are likely to offer as reasons for believing your mission is dumb, or impractical, or downright impossible—and then deciding what you’ll say or do to prove these predictions and opinions wrong. In all likelihood, each of these pessimistic expectations represents an individual ingredient in the “negative stew” that saps energy from your sense of mission. Debunking each one in turn progressively weakens the stew’s flavor until it eventually feels like nothing more than so much hot water.

84Where the real power of this exercise lies, however, is in the way planning to disprove a specific negative expectation often leads to a refinement of the strategy that actually increases its chances of success—thereby generating a more positive expectation. This is how dreamcrafters turn negative expectations into positive ones. The more they anticipate what the naysayers will give as reasons why the dream won’t come true, the more they clarify what they must do to ensure it will. The same way a judo master uses an opponent’s own energy to deflect and throw an opponent, the dreamcrafter channels the negative “won’t” power of these pessimistic projections into a store of positive “will” power to strengthen his or her conviction that success is a foregone conclusion. The no-willpower myth simply cannot endure alongside healthy reserves of optimistic “will” power.

The actual exercise is simple and easy, though once again paper and pencil are required. Better get several sheets of paper; we promise to wait for you and go no further until you’re back and have resumed reading.

Step One: Listing Reasons Why Your Dream Is Not Such a Good Idea

The objective here is not just to anticipate what those in your immediate environment might raise as objections, but the serious, legitimate reasons any real or imaginary person—including yourself—might offer to persuade you to abandon your mission. List them in whatever order they come to mind. When your list is complete, precede each item with an identifying letter, so that the first item is identified as item A, the sec- ond as B, and so on. (If there are more than twenty-six in all, [yikes!], make number twenty-seven AA, followed by BB, etc.)

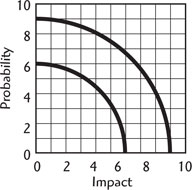

85Step Two: Creating a Probability/Impact Grid

On a separate sheet of paper (the larger the better), draw a grid like that illustrated. Make it large enough to give you room to work. Draw two arcs that roughly connect “position 6” on both axes, and “position 9” on both as well, as in the illustration.

When the grid is complete, your task is to subject each item on your list to a twofold evaluation. First, if you were to do nothing to counter it, what (in your estimation) is the probability that this negative projection would be realized? (A rating of 10 represents the highest probability—a virtual certainty, unless you act to prevent it.) Second, if this negative projection were realized, how great would its impact be on you? (A rating of 10 represents the highest impact—a virtual calamity, unless you act to prevent it.) For each negative item on your list, plot that item’s identifying letter on the grid, according to its probability and impact ratings.

Step Three: Debunking Your Top Items

Those items (if any) that occupy the upper-right corner of the grid, above or to the right of the larger arc, are the ones you consider most probable and most impactful. (If none of your items scored their way into this section of the grid, focus on the high-scoring items in the central section.) Now you must get creative and strategize how you intend to ensure that these pessimistic predictions do not come true, or that these negative opinions do not prove to have been justified.

86A good place to begin involves extracting the “grain of truth” hidden within each item. Let’s say the first one reads something like “You haven’t got a chance. You never stick with things long enough to bring them to completion.” In your heart, you may feel this has no validity, because you know that you have in fact brought many things to completion. Still, in anticipating that someone might make this negative comment, you’re acknowledging that something would have led that person to this (false) conclusion. In searching for the grain of truth, you attempt to isolate what lies behind the comment. Perhaps such a remark might come from someone who only witnessed those very few occasions where you did not complete something, for example. So the grain of truth might be, “I don’t always stick with things through to completion.” For the comment, “This will cost way too much money, money we can’t possibly afford,” the grain of truth might be “There are certain costs involved.”

On a fresh sheet of paper, write down the grain of truth behind your highest-scoring naysayer comment—and then below it, jot down any ideas you have to disprove this comment in the eyes of your hypothetical naysayer in word or deed. In the failure-to-see-things-through example, ideas might include something like “I’ll create a ‘Countdown to Completion’ wall chart, and post it in a highly visible location, and update it every day so everyone can see my progress toward completion, and my determination to reach it.” For the cost issue, an idea might be “Here is my estimate of total costs, and here is how I intend to reapply some of my own existing expenses to cover these costs so that no new debts are incurred and no one but me is affected in any way.”

Bingo—the fear that you won’t stick with the dream (a negative expectation) has led you to create a motivational tool that greatly increases your confidence that you will see it through (a positive expectation).

87- Negative expectation: “My efforts will attract attention that will embarrass other members of my family.”

- Positive expectation: “I will draw attention to how other members of my family are supporting me, always in a way that enhances their self-image and self esteem.”

- Negative: “The amount of time I’ll have to devote to this in the evenings will place a serious strain on my marriage.”

- Positive: “I’ll do all the unpleasant stuff myself, and will pass all the more enjoyable aspects on to my spouse as a mechanism to increase his/her involvement and thereby strengthen my marriage.”

With a little imagination, virtually any fear can be transformed into a strategy for alignment, a method for increasing the chances of success. As these increase, so too does the feeling of confidence that success will be achieved. This optimistic confidence is the motivational fuel of dreamcrafting.

Dare to Declare

In our survey of ways to generate motivational drive, there is another powerful technique to ignite the fires of determination.

“I think we have everything we need for the party,” says the husband. “Did you remember your lighter?”

“Oh, I won’t be needing that,” says the wife.

“You won’t? Why not?”

“Because I quit smoking.”

“You did? When?”

“Oh, a while back …”

“Really? That’s great! How’s it been going?”

“Well, so far so good, I guess …”

88This is the way many people disclose the fact that they have decided to pursue a dream: quietly off-handedly, after the fact, as if the whole thing is mildly embarrassing, even mildly distasteful. (“Oh, please don’t make a big fuss, I don’t even know if it’s going to work …!”)

This is the voice of the not-quite-convinced, of the almost-committed, of the not-yet-fully-determined-to-succeed. This is a disclosure strategy to minimize humiliation if the effort fails; it is a strategy dictated by fear of failure. Where there is an expectation of failure, of course, failure itself usually follows.

The skillful dreamcrafter, having replaced negative expectations with positive ones, now kick starts the motivational engine by planting the flag, burning the bridges, setting fire to the boats. With appropriate drama and fanfare, and before any key first steps are taken, the mission is formally declared to family and friends and virtually anyone who’ll listen.

The purpose of declaration is to convey (in a gentle, tactful, diplomatic way) that naysayers will find no fear of failure to seize on here, that there is only a calm and assured anticipation of success. This is communicated by outlining not only the dream itself, but all of the alignment components derived from the “grain of truth” exercise outlined above. The whole is presented like a detailed tactical plan:

“My weight loss will be the result of both diet and exercise. I intend to visit Doctor Gaines next week to find out what supplements I’ll need for my diet. For exercise, I’m going to begin by walking to the park and back every evening. Kelly, this means if there are some nights you don’t feel like walking the dog, I’ll be very happy to take over for you on those occasions. Or you may want to make it a point of coming with me, which I’d love! Because I’ll be cutting way back on beer consumption, I’ll be keeping a record of how much of my old beer budget I’m saving, and that’ll be on this chart, hanging near the bar in the rec room. Once I’ve put enough aside, I’ll apply it to the purchase of a treadmill, which will make my walking more enjoyable when the weather turns miserable. That means the treadmill won’t cut into any other household expenses or the kids’ allowances.”

The declaration makes extensive use of the word “will,” to maximize the “willpower” effect. Though it can never preclude every possible naysayer objection, it addresses those that are most obvious and immediate before they can even be raised. In anticipation of the discussion on “measurement” in the next chapter, it may assign a measure of success to each of the tactical components: “I’m hoping to get you involved in this, honey, [in such-and-such a way], and I’ll know it’s working the day I overhear you telling your mother something like ‘This is the best thing that ever happened in our marriage.’” And in anticipation of the section on soliciting the support of others in chapter 8, the declaration should invite such support outright: “Now what I need to know is, can I count on all of you to get behind me with this thing? Your support is going to make it a lot easier for me to make this happen.”

As we’ll explore more fully in chapter 9, taking a leadership position means the “declaration” never ends. The dreamcrafter reinforces the no-going-back nature of the commitment at every opportunity. For someone undertaking to become more fit through walking, “declaration” may involve parading visibly to the front door in track clothes day after day, rather than trying to slink out the back way so no one will notice; it may mean returning all sweaty with a cheerful attention-grabbing, “Whew! It’s hot out there!”

The greater the demonstration of commitment to the mission at the very outset, the harder it becomes to conceive of abandoning the mission before success is achieved. This is where declaration derives its motivational power. Its message becomes “The die is cast, there’s no turning back, I’m on a mission, and I’m going for it all the way!”

Motivation, Phase One: To ignite a powerful sense of mission from the very beginning:

- Restore Murphy’s Law to its original “joke” status

- Retire the no-willpower myth for all time

- Transform negative expectations into positive ones

- Make a declaration of total commitment to the mission

Motivation, Phase Two: To sustain this powerful sense of mission over the long term:

- Create motivational reenergizers designed to kick in at key intervals (as outlined in the following chapter)

90

GALLERY OF DREAMCRAFTERS

JANE GOODALL (1934- )

The Big Dream

Before her second birthday, Valerie Jane Goodall was given a lifelike toy chimpanzee by her father, in honor of a baby chimp born at the London Zoo. Friends of the family were concerned that this realistic toy might inspire nightmares for the child, but Jane loved it. A few years later, on a visit to a farm, she helped collect eggs, and was eager to discover how the eggs emerged from the hens; in an early demonstration of her inquisitive nature, she hid in the henhouse for hours to get to the bottom of the mystery, so to speak.

As a youngster, Jane dreamed of going to Africa to live with the animals and write books about them. (Years later she would joke that in part it was because she was jealous of Tarzan’s Jane, and believed she would have made a better Jane for him.) Her mother provided strong encouragement that promoted positive expectations, often telling her, “If you never give up, you will find a way.”

The way materialized in 1957, when she made her first trip to Africa to visit a friend in Kenya. She met Dr. Louis Leakey, and became his assistant on fossil-hunting expeditions. Though she briefly considered a career in paleontology, “my childhood dream was as strong as ever,” as she put it. Paleontologists study dead animals; “I still wanted to work with living animals. I wanted to learn things that no one else knew, uncover secrets through patient observation. I wanted to come as close to talking to animals as I could.”

91Within three years she’d begun her formal research at Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania. It was not long before she began making important discoveries. In 1965 the National Geographic Society produced a television documentary that showcased her findings—in particular that chimps used tools and were highly intelligent emotional creatures living in complex social groups. That same year, she became one of only a handful of people in the world to earn a doctoral degree (from England’s Cambridge University) without first having a bachelor’s degree.

Jane’s first book, My Friends the Wild Chimpanzees, was published in 1967, the same year she became Scientific Director of the Gombe Stream Research Center. This was followed by other books, honorary degrees from universities around the world, and appointments as trustee or director in scores of anthropological, philosophical, and educational organizations and societies.

In 1977 she founded the Jane Goodall Institute, based in Connecticut. The mission of the institute is to advance the power of individuals to take informed and compassionate action to improve the environment of all living things—in short, to improve life on earth.

Jane’s landmark work, the longest running research project of its kind, continues to yield groundbreaking results. She travels extensively to help people realize that what they do individually truly makes a difference.

The toy chimpanzee she was given on her second birthday still sits in a chair in her home in England.

Basic Values

- Every single individual matters, including nonhumans

- The way each one of us lives our life does matter, does make a difference

- Learning, learning, learning comes before everything else

- Science does not have to be dispassionate

92

What the Naysayers Were Saying

- This woman will not last more than three weeks in the wild.

- It’s absurd for her to be giving the chimps names. They should be given numbers. Chimps do not have personalities, only humans do.

- Her chimp sanctuaries are very costly and do not help conserve habitat, which is needed to protect the species.

- Her advisor, Robert Hinde, insisted her methods were not professional. Her colleagues and classmates agreed she was “doing it all wrong.”

The Darkest Hour

Jane Goodall found herself struggling against professional criticism of her methods throughout her research career. A year after surviving a near-fatal air crash, she almost lost the opportunity to continue her work when several fellow researchers were abducted by kidnappers at Gombe. But her darkest moment was the death of her second husband in 1980.

She confessed to sometimes feeling “… stranded in a placid backwater that knew not, cared not, that I was there.” At the worst of times, she felt she was “… being sucked under by strong unknowing currents toward annihilation.”

“Yet somehow,” she writes, looking back over her life, “I believe that I was following some overall plan.” She could be describing the alignment of an aspirational field when she describes how the “flotsam speck” that was herself “was being gently nudged or fiercely blown along a very specific route by an unseen, intangible Wind.”

Validation and Vindication

- Received the J. Paul Getty Wildlife Conservation Prize (for “helping millions of people understand the importance of wildlife conservation to life on this planet”) in 1984.

- Received the Encyclopædia Britannica Award for Excellence on the Dissemination of Learning for the Benefit of Mankind in 1988.

- Received the National Geographic Society Hubbard Medal for distinction in exploration, discovery, and research in 1995.

- (Meredith Small, anthropologist at Cornell University): “I have several young women every year come to my office telling me they want to become an animal behaviorist like Goodall. She opened the door for women who dream of doing fieldwork.”

93

Memorable Sayings

- “We humans are incredibly resilient, and I don’t think it’s ever too late.”

- “Young people, when informed and empowered, when they realize that what they do truly makes a difference, can indeed change the world.”

- “Humans have accomplished ‘impossible’ tasks before.”

- “Let us have faith in ourselves.”