Suppose, for just a moment, that you wish to ship Python

programs to an audience that may be in the very early stages of

evolving from computer user to computer programmer. Maybe you are

shipping a Python application to nontechnical users, or perhaps you’re

interested in shipping a set of Python demo programs with a book.

Whatever the reason, some of the people who will use your software

can’t be expected to do anything more than click a mouse. They

certainly won’t be able to edit their system configuration files to

set things such as PATH and

PYTHONPATH per your programs’

assumptions. Your software will have to configure itself.

Luckily, Python scripts can do that too. In the next three sections, we’re going to study three modules that aim to automatically launch programs with minimal assumptions about the environment on the host machine:

- Launcher.py

A library of tools for automatically configuring the shell environment in preparation for launching a Python script. It can be used to set required shell variables—both the

PATHsystem program search path (used to find the “python” executable) and thePYTHONPATHmodule search path (used to resolve imports within scripts). Because such variable settings made in a parent program are inherited by spawned child programs, this interface lets scripts preconfigure search paths for other scripts.- LaunchBrowser.py

Aims to portably locate and start an Internet browser program on the host machine in order to view a local file or remote web page. It uses tools in Launcher.py to search for a reasonable browser to run.

- Playfile.py

Provides tools for opening media files with either a platform-specific player or a general web browser. It can play audio, images, and video, and it uses the Python library’s

webbrowserandmimetypesmodules to do some of its work.

All of these modules are designed to be reusable in any context where you want your software to be user friendly. By searching for files and configuring environments automatically, your users can avoid (or at least postpone) having to learn the intricacies of environment configuration.

The three modules in this section see action in many

of this book’s examples. In fact, we’ve already used some of these

tools. The launchmodes script we

met at the end of the prior chapter imported Launcher functions to hunt for the local

python.exe interpreter’s path, needed by

os.spawnv calls. That script

could have assumed that everyone who installs it on their machine

will edit its source code to add their own Python location; but the

technical know-how required for even that task is already

light-years beyond many potential users.[*] It’s much nicer to invest a negligible amount of

startup time to locate Python automatically.

The two modules listed in Examples 6-14 and 6-15, together with launchmodes of the prior chapter, also

form the core of the demo-launcher programs at

the top of the examples distribution tree. There’s nothing quite

like being able to witness programs in action first hand, so I

wanted to make it as easy as possible to launch the Python examples

in this book. Ideally, they should run straight from the book

examples distribution package when clicked, and not require readers

to wade through a complex environment installation procedure.

However, many demos perform cross-directory imports and so

require the book’s module package directories to be installed in

PYTHONPATH; it is not enough just

to click on some programs’ icons at random. Moreover, when first

starting out, users can’t be assumed to have added the Python

executable to their system search path either; the name “python”

might not mean anything in the shell.

At least on platforms tested thus far, the following two

modules solve such configuration problems. For example, the

Launch_PyDemos.pyw script in the root directory

automatically configures the system and Python execution

environments using Launcher.py tools, and then

spawns PyDemos2.pyw, a Tkinter GUI demo interface we’ll meet in Chapter 10. PyDemos in turn uses

launchmodes to spawn other

programs that also inherit the environment settings made at the top.

The net effect is that clicking any of the Launch_* scripts starts Python programs

even if you haven’t touched your environment settings at all.

You still need to install Python if it’s not present, of course, but the Python Windows self-installer is a simple point-and-click affair too. Because searches and configuration take extra time, it’s still to your advantage to eventually configure your environment settings and run programs such as PyDemos directly instead of through the launcher scripts. But there’s much to be said for instant gratification when it comes to software.

These tools will show up in other contexts later in this text.

For instance, a GUI example in Chapter 11, big_gui, will use a Launcher tool to locate canned Python

source-distribution demo programs in arbitrary and unpredictable

places on the underlying computer.

The LaunchBrowser script in

Example 6-15 also uses

Launcher to locate suitable web

browsers and is itself used to start Internet demos in the PyDemos

and PyGadgets launcher GUIs—that is, Launcher starts PyDemos, which starts

LaunchBrowser, which uses

Launcher. By optimizing

generality, these modules also optimize reusability.

Because the Launcher.py file is

heavily documented, I won’t go over its fine points in narrative

here. Instead, I’ll just point out that all of its functions are

useful by themselves, but the main entry point is the launchBookExamples function near the end;

you need to work your way from the bottom of this file up in order

to glimpse its larger picture.

The launchBookExamples

function uses all the others to configure the environment and then

spawn one or more programs to run in that environment. In fact, the

top-level demo launcher scripts shown in Examples 6-12 and 6-13 do nothing more than ask

this function to spawn GUI demo interface programs we’ll meet in

Chapter 10 (e.g.,

PyDemos2.pyw and

PyGadgets_bar.pyw). Because the GUIs are

spawned indirectly through this interface, all programs they spawn

inherit the environment configurations too.

Example 6-12. PP3ELaunch_PyDemos.pyw

#!/bin/env python ################################################## # PyDemos + environment search/config first # run this if you haven't set up your paths yet # you still must install Python first, though ################################################## import Launcher Launcher.launchBookExamples(['PyDemos2.pyw'], trace=False)

Example 6-13. PP3ELaunch_PyGadgets_bar.pyw

#!/bin/env python ################################################## # PyGadgets_bar + environment search/config first # run this if you haven't set up your paths yet # you still must install Python first, though ################################################## import Launcher Launcher.launchBookExamples(['PyGadgets_bar.pyw'], trace=False)

When run directly, PyDemos2.pyw and

PyGadgets_bar.pyw instead rely on the

configuration settings on the underlying machine. In other words,

Launcher effectively hides

configuration details from the GUI interfaces by enclosing them in a

configuration program layer. To understand how, study Example 6-14.

Example 6-14. PP3ELauncher.py

#!/usr/bin/env python

"""

==========================================================================

Tools to find files, and run Python demos even if your environment has

not been manually configured yet. For instance, provided you have already

installed Python, you can launch Tkinter GUI demos directly from the book's

examples distribution tree by double-clicking this file's icon, without

first changing your environment configuration.

Assumes Python has been installed first (double-click on the python self

installer on Windows), and tries to find where Python and the examples

distribution live on your machine. Sets Python module and system search

paths before running scripts: this only works because env settings are

inherited by spawned programs on both Windows and Linux.

You may want to edit the list of directories searched for speed, and will

probably want to configure your PYTHONPATH eventually to avoid this

search. This script is friendly to already-configured path settings,

and serves to demo platform-independent directory path processing.

Python programs can always be started under the Windows port by clicking

(or spawning a 'start' DOS command), but many book examples require the

module search path too for cross-directory package imports.

==========================================================================

"""

import sys, os

try:

PyInstallDir = os.path.dirname(sys.executable)

except:

PyInstallDir = r'C:Python24' # for searches, set for older pythons

BookExamplesFile = 'README-PP3E.txt' # for pythonpath configuration

def which(program, trace=True):

"""

Look for program in all dirs in the system's search

path var, PATH; return full path to program if found,

else None. Doesn't handle aliases on Unix (where we

could also just run a 'which' shell cmd with os.popen),

and it might help to also check if the file is really

an executable with os.stat and the stat module, using

code like this: os.stat(filename)[stat.ST_MODE] & 0111

"""

try:

ospath = os.environ['PATH']

except:

ospath = '' # OK if not set

systempath = ospath.split(os.pathsep)

if trace: print 'Looking for', program, 'on', systempath

for sysdir in systempath:

filename = os.path.join(sysdir, program) # adds os.sep between

if os.path.isfile(filename): # exists and is a file?

if trace: print 'Found', filename

return filename

else:

if trace: print 'Not at', filename

if trace: print program, 'not on system path'

return None

def findFirst(thisDir, targetFile, trace=False):

"""

Search directories at and below thisDir for a file

or dir named targetFile. Like find.find in standard

lib, but no name patterns, follows Unix links, and

stops at the first file found with a matching name.

targetFile must be a simple base name, not dir path.

could also use os.walk or os.path.walk to do this.

"""

if trace: print 'Scanning', thisDir

for filename in os.listdir(thisDir): # skip . and ..

if filename in [os.curdir, os.pardir]: # just in case

continue

elif filename == targetFile: # check name match

return os.path.join(thisDir, targetFile) # stop at this one

else:

pathname = os.path.join(thisDir, filename) # recur in subdirs

if os.path.isdir(pathname): # stop at 1st match

below = findFirst(pathname, targetFile, trace)

if below: return below

def guessLocation(file, isOnWindows=(sys.platform[:3]=='win'), trace=True):

"""

Try to find directory where file is installed

by looking in standard places for the platform.

Change tries lists as needed for your machine.

"""

cwd = os.getcwd( ) # directory where py started

tryhere = cwd + os.sep + file # or os.path.join(cwd, file)

if os.path.exists(tryhere): # don't search if it is here

return tryhere # findFirst(cwd,file) descends

if isOnWindows:

tries = []

for pydir in [PyInstallDir, r'C:Program FilesPython']:

if os.path.exists(pydir):

tries.append(pydir)

tries = tries + [cwd, r'C:Program Files']

for drive in 'CDEFG':

tries.append(drive + ':')

else:

tries = [cwd, os.environ['HOME'], '/usr/bin', '/usr/local/bin']

for dir in tries:

if trace: print 'Searching for %s in %s' % (file, dir)

try:

match = findFirst(dir, file)

except OSError:

if trace: print 'Error while searching', dir # skip bad drives

else:

if match: return match

if trace: print file, 'not found! - configure your environment manually'

return None

PP3EpackageRoots = [ # python module search path

#'%sPP3E' % os.sep, # pass in your own elsewhere

''] # '' adds examplesDir root

def configPythonPath(examplesDir, packageRoots=PP3EpackageRoots, trace=True):

"""

Set up the Python module import search-path directory

list as necessary to run programs in the book examples

distribution, in case it hasn't been configured already.

Add examples package root + any nested package roots

that imports are relative to (just top root currently).

os.environ assignments call os.putenv internally in 1.5+,

so these settings will be inherited by spawned programs.

Python source lib dir and '.' are automatically searched;

unix|win os.sep is '/' | '', os.pathsep is ':' | ';'.

sys.path is for this process only--must set os.environ.

adds new dirs to front, in case there are two installs.

"""

try:

ospythonpath = os.environ['PYTHONPATH']

except:

ospythonpath = '' # OK if not set

if trace: print 'PYTHONPATH start:

', ospythonpath

addList = []

for root in packageRoots:

importDir = examplesDir + root

if importDir in sys.path:

if trace: print 'Exists', importDir

else:

if trace: print 'Adding', importDir

sys.path.append(importDir)

addList.append(importDir)

if addList:

addString = os.pathsep.join(addList) + os.pathsep

os.environ['PYTHONPATH'] = addString + ospythonpath

if trace: print 'PYTHONPATH updated:

', os.environ['PYTHONPATH']

else:

if trace: print 'PYTHONPATH unchanged'

def configSystemPath(pythonDir, trace=True):

"""

Add python executable dir to system search path if needed

"""

try:

ospath = os.environ['PATH']

except:

ospath = '' # OK if not set

if trace: print 'PATH start:

', ospath

if ospath.lower().find(pythonDir.lower( )) == -1: # not found?

os.environ['PATH'] = ospath + os.pathsep + pythonDir # not case diff

if trace: print 'PATH updated:

', os.environ['PATH']

else:

if trace: print 'PATH unchanged'

def runCommandLine(pypath, exdir, command, isOnWindows=0, trace=True):

"""

Run python command as an independent program/process on

this platform, using pypath as the Python executable,

and exdir as the installed examples root directory.

Need full path to Python on Windows, but not on Unix.

On Windows, an os.system('start ' + command) is similar,

except that .py files pop up a DOS console box for I/O.

Could use launchmodes.py too but pypath is already known.

"""

command = exdir + os.sep + command # rooted in examples tree

command = os.path.normpath(command) # fix up mixed slashes

os.environ['PP3E_PYTHON_FILE'] = pypath # export directories for

os.environ['PP3E_EXAMPLE_DIR'] = exdir # use in spawned programs

if trace: print 'Spawning:', command

if isOnWindows:

os.spawnv(os.P_DETACH, pypath, ('python', command))

else:

cmdargs = [pypath] + command.split( )

if os.fork( ) == 0:

os.execv(pypath, cmdargs) # run prog in child process

def launchBookExamples(commandsToStart, trace=True):

"""

Toplevel entry point: find python exe and examples dir,

configure environment, and spawn programs. Spawned

programs will inherit any configurations made here.

"""

isOnWindows = (sys.platform[:3] == 'win')

pythonFile = (isOnWindows and 'python.exe') or 'python'

if trace:

print os.getcwd( ), os.curdir, os.sep, os.pathsep

print 'starting on %s...' % sys.platform

# find python executable: check system path, then guess

try:

pypath = sys.executable # python executable running me

except:

# on older pythons

pypath = which(pythonFile) or guessLocation(pythonFile, isOnWindows)

assert pypath

pydir, pyfile = os.path.split(pypath) # up 1 from file

if trace:

print 'Using this Python executable:', pypath

raw_input('Press <enter> key')

# find examples root dir: check cwd and others

expath = guessLocation(BookExamplesFile, isOnWindows)

assert expath

updir = expath.split(os.sep)[:-2] # up 2 from file

exdir = os.sep.join(updir) # to PP3E pkg parent

if trace:

print 'Using this examples root directory:', exdir

raw_input('Press <enter> key')

# export python and system paths if needed

configSystemPath(pydir)

configPythonPath(exdir)

if trace:

print 'Environment configured'

raw_input('Press <enter> key')

# spawn programs: inherit configs

for command in commandsToStart:

runCommandLine(pypath, os.path.dirname(expath), command, isOnWindows)

if _ _name_ _ == '_ _main_ _':

#

# if no args, spawn all in the list of programs below

# else rest of cmd line args give single cmd to be spawned

#

if len(sys.argv) == 1:

commandsToStart = [

'Gui/TextEditor/textEditor.py', # either slash works

'Lang/Calculator/calculator.py', # launcher normalizes path

'PyDemos2.pyw',

#'PyGadgets.py',

'echoEnvironment.pyw'

]

else:

commandsToStart = [ ' '.join(sys.argv[1:]) ]

launchBookExamples(commandsToStart)

if sys.platform[:3] == 'win':

raw_input('Press Enter') # to read msgs if clickedOne way to understand the launcher script is to trace the

messages it prints along the way. When run on my Windows test

machine for the third edition of this book, I have a PYTHONPATH but have not configured my

PATH to include Python. Here is

the script’s trace output:

C:...PP3E>Launcher.py

C:MarkPP3E-cdExamplesPP3E . ;

starting on win32...

Using this Python executable: C:Python24python.exe

Press <enter> key

Using this examples root directory: C:MarkPP3E-cdExamples

Press <enter> key

PATH start:

C:WINDOWSsystem32;...more deleted...;C:Program FilesMySQLMySQL Server

4.1in

PATH updated:

C:WINDOWSsystem32;...more deleted...;C:Program FilesMySQLMySQL Server 4.1in;

C:Python24

PYTHONPATH start:

C:MarkPP3E-cdExamples;C:MarkPP2E-cdExamples

Exists C:MarkPP3E-cdExamples

PYTHONPATH unchanged

Environment configured

Press <enter> key

Spawning: C:MarkPP3E-cdExamplesPP3EGuiTextEditor extEditor.py

Spawning: C:MarkPP3E-cdExamplesPP3ELangCalculatorcalculator.py

Spawning: C:MarkPP3E-cdExamplesPP3EPyDemos2.pyw

Spawning: C:MarkPP3E-cdExamplesPP3EechoEnvironment.pyw

Press EnterFour programs are spawned with PATH and PYTHONPATH preconfigured according to the

location of your Python interpreter program, the location of your

examples distribution tree, and the list of required PYTHONPATH entries in the script variable,

PP3EpackageRoots.

Just one directory needs to be added to PYTHONPATH for book examples today—the one

containing the PP3E root directory—since all

cross-directory imports are package paths relative to the

PP3E root. That makes it easier to configure,

but the launcher code still supports a list of entries for

generality (it may be used for a different tree).

To demonstrate, let’s look at some trace outputs obtained with

different configurations in the past. When run by itself without a

PYTHONPATH setting, the script

finds a suitable Python and the examples root directory (by hunting

for its README file), uses those results to configure PATH and PYTHONPATH settings if needed and spawns a

precoded list of program examples. For example, here is a launch on

Windows with an empty PYTHONPATH,

a different directory structure, and an older version of

Python:

C: empexamples>set PYTHONPATH=C: empexamples>python Launcher.pyC: empexamples . ; starting on win32... Looking for python.exe on ['C:\WINDOWS', 'C:\WINDOWS', 'C:\WINDOWS\COMMAND', 'C:\STUFF\BIN.MKS', 'C:\PROGRAM FILES\PYTHON'] Not at C:WINDOWSpython.exe Not at C:WINDOWSpython.exe Not at C:WINDOWSCOMMANDpython.exe Not at C:STUFFBIN.MKSpython.exe Found C:PROGRAM FILESPYTHONpython.exe Using this Python executable: C:PROGRAM FILESPYTHONpython.exe Press <enter> key Using this examples root directory: C: empexamples Press <enter> key PATH start C:WINDOWS;C:WINDOWS;C:WINDOWSCOMMAND;C:STUFFBIN.MKS; C:PROGRAM FILESPYTHON PATH unchanged PYTHONPATH start: Adding C: empexamplesPart3 Adding C: empexamplesPart2 Adding C: empexamplesPart2Gui Adding C: empexamples PYTHONPATH updated: C: empexamplesPart3;C: empexamplesPart2;C: empexamplesPart2Gui; C: empexamples; Environment configured Press <enter> key Spawning: C: empexamplesPart2GuiTextEditor extEditor.pyw Spawning: C: empexamplesPart2LangCalculatorcalculator.py Spawning: C: empexamplesPyDemos.pyw Spawning: C: empexamplesechoEnvironment.pyw

When used by the PyDemos launcher script, Launcher does not pause for key presses

along the way (the trace argument is passed in false). Here is the

output generated when using the module to launch PyDemos with

PYTHONPATH already set to include

all the required directories; the script both avoids adding settings

redundantly and retains any exiting settings already in your

environment (again, this reflects an older tree structure and Python

install to demonstrate the search capabilities of the

script):

C:PP3rdEdexamples>python Launch_PyDemos.pyw

Looking for python.exe on ['C:\WINDOWS', 'C:\WINDOWS',

'C:\WINDOWS\COMMAND', 'C:\STUFF\BIN.MKS', 'C:\PROGRAM FILES\PYTHON']

Not at C:WINDOWSpython.exe

Not at C:WINDOWSpython.exe

Not at C:WINDOWSCOMMANDpython.exe

Not at C:STUFFBIN.MKSpython.exe

Found C:PROGRAM FILESPYTHONpython.exe

PATH start C:WINDOWS;C:WINDOWS;C:WINDOWSCOMMAND;C:STUFFBIN.MKS;

C:PROGRAM FILESPYTHON

PATH unchanged

PYTHONPATH start:

C:PP3rdEdexamplesPart3;C:PP3rdEdexamplesPart2;C:PP3rdEdexamples

Part2Gui;C:PP3rdEdexamples

Exists C:PP3rdEdexamplesPart3

Exists C:PP3rdEdexamplesPart2

Exists C:PP3rdEdexamplesPart2Gui

Exists C:PP3rdEdexamples

PYTHONPATH unchanged

Spawning: C:PP3rdEdexamplesPyDemos.pywAnd finally, here is the trace output of a launch on my Linux

system; because Launcher is

written with portable Python code and library calls, environment

configuration and directory searches work just as well there:

[mark@toy ~/PP3rdEd/examples]$unsetenv PYTHONPATH[mark@toy ~/PP3rdEd/examples]$python Launcher.py/home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples . / : starting on linux2... Looking for python on ['/home/mark/bin', '.', '/usr/bin', '/usr/bin', '/usr/local/ bin', '/usr/X11R6/bin', '/bin', '/usr/X11R6/bin', '/home/mark/ bin', '/usr/X11R6/bin', '/home/mark/bin', '/usr/X11R6/bin'] Not at /home/mark/bin/python Not at ./python Found /usr/bin/python Using this Python executable: /usr/bin/python Press <enter> key Using this examples root directory: /home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples Press <enter> key PATH start /home/mark/bin:.:/usr/bin:/usr/bin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/X11R6/bin:/bin:/ usr /X11R6/bin:/home/mark/bin:/usr/X11R6/bin:/home/mark/bin:/usr/X11R6/bin PATH unchanged PYTHONPATH start: Adding /home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples/Part3 Adding /home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples/Part2 Adding /home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples/Part2/Gui Adding /home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples PYTHONPATH updated: /home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples/Part3:/home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples/Part2:/home/ mark/PP3rdEd/examples/Part2/Gui:/home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples: Environment configured Press <enter> key Spawning: /home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples/Part2/Gui/TextEditor/textEditor.py Spawning: /home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples/Part2/Lang/Calculator/calculator.py Spawning: /home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples/PyDemos.pyw Spawning: /home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples/echoEnvironment.pyw

In all but the first of these launches, the Python interpreter

was found on the system search path, so no real searches were

performed (the Not at lines near

the top represent the module’s which function, and the first launch used

the more recent sys.executable

instead of searching). In a moment, we’ll also use the launcher’s

which and guessLocation functions to look for web

browsers in a way that kicks off searches in standard install

directory trees. Later in the book, we’ll use this module in other

ways—for instance, to search for demo programs and source code files

somewhere on the machine with calls of this form:

C: emp>python>>>from PP3E.Launcher import guessLocation>>>guessLocation('hanoi.py')Searching for hanoi.py in C:Program FilesPython Searching for hanoi.py in C: empexamples Searching for hanoi.py in C:Program Files Searching for hanoi.py in C: 'C:\PP3rdEd\cdrom\Python1.5.2\SourceDistribution\Unpacked\Python-1.5.2 \Demo\tkinter\guido\hanoi.py' >>>from PP3E.Launcher import findFirst>>>findFirst('.', 'PyMailGui.py')'.\examples\Internet\Email\PyMailGui.py' >>>findFirst('.', 'peoplecgi.py', True)Scanning . Scanning .PP3E Scanning .PP3EPreview Scanning .PP3EPreview.idlerc Scanning .PP3EPreviewcgi-bin '.\PP3E\Preview\cgi-bin\peoplecgi.py'

Such searches aren’t necessary if you can rely on an

environment variable to give at least part of the path to a file;

for instance, paths scripts within the PP3E

examples tree can be named by joining the PP3EHOME shell variable with the rest of

the script’s path (assuming the rest of the script’s path won’t

change and that we can rely on that shell variable being set

everywhere).

Some scripts may also be able to compose relative paths to

other scripts using the sys.path[0] home-directory indicator added

for imports (see Chapter 3).

But in cases where a file can appear at arbitrary places, searches

like those shown previously are sometimes the best scripts can do.

The earlier hanoi.py program file, for example,

can be anywhere on the underlying machine (if present at all);

searching is a more user-friendly final alternative than simply

giving up.

Web browsers can do amazing things these days. They can serve as document viewers, remote program launchers, database interfaces, media players, and more. Being able to open a browser on a local or remote page file from within a script opens up all kinds of interesting user-interface possibilities. For instance, a Python system might automatically display its HTML-coded documentation when needed by launching the local web browser on the appropriate page file.[*] Because most browsers know how to present pictures, audio files, and movie clips, opening a browser on such a file is also a simple way for scripts to deal with multimedia generically.

The next script listed in this chapter is less ambitious than Launcher.py, but equally reusable: LaunchBrowser.py attempts to provide a portable interface for starting a web browser. Because techniques for launching browsers vary per platform, this script provides an interface that aims to hide the differences from callers. Once launched, the browser runs as an independent program and may be opened to view either a local file or a remote page on the Web.

Here’s how it works. Because most web browsers can be started

with shell command lines, this script simply builds and launches one

as appropriate. For instance, to run a Netscape browser on Linux, a

shell command of the form netscape

url is run, where url

begins with file:// for local

files and http:// for live

remote-page accesses (this is per URL conventions we’ll meet in more

detail later in Chapter 16).

On Windows, a shell command such as start

url achieves the same goal. Here are some

platform-specific highlights:

- Windows platforms

On Windows, the script either opens browsers with DOS

startcommands or searches for and runs browsers with theos.spawnvcall. On this platform, browsers can usually be opened with simple start commands (e.g.,os.system("start xxx.html")). Unfortunately,startrelies on the underlying filename associations for web page files on your machine, picks a browser for you per those associations, and has a command-line length limit that this script might exceed for long local file paths or remote page addresses.Because of that, this script falls back on running an explicitly named browser with

os.spawnv, if requested or required. To do so, though, it must find the full path to a browser executable. Since it can’t assume that users will add it to thePATHsystem search path (or this script’s source code), the script searches for a suitable browser withLaunchermodule tools in both directories onPATHand in common places where executables are installed on Windows.- Unix-like platforms

On other platforms, the script relies on

os.systemand the systemPATHsetting on the underlying machine. It simply runs a command line naming the first browser on a candidates list that it can find on yourPATHsetting. Because it’s much more likely that browsers are in standard search directories on platforms like Unix and Linux (e.g.,/usr/bin), the script doesn’t look for a browser elsewhere on the machine. Notice the&at the end of the browser command-line run; without it,os.systemcalls block on Unix-like platforms.

All of this is easily customized (this is Python code, after

all), and you may need to add additional logic for other platforms.

But on all of my machines, the script makes reasonable assumptions

that allow me to largely forget most of the platform-specific bits

previously discussed; I just call the same launchBrowser function everywhere. For

more details, let’s look at Example 6-15.

Example 6-15. PP3ELaunchBrowser.py

#!/bin/env python

#############################################################################

# Launch a web browser to view a web page, portably. If run in '-live'

# mode, assumes you have an Internet feed and opens page at a remote site.

# Otherwise, assumes the page is a full file pathname on your machine,

# and opens the page file locally. On Unix/Linux, finds first browser

# on your $PATH. On Windows, tries DOS "start" command first, or searches

# for the location of a browser on your machine for os.spawnv by checking

# PATH and common Windows executable directories. You may need to tweak

# browser executable name/dirs if this fails. This has only been tested in

# Windows and Linux; you may need to add more code for other machines (mac:

# ic.launcurl(url)?). See also the new standard library webbrowser module.

#############################################################################

import os, sys

from Launcher import which, guessLocation # file search utilities

useWinStart = False # 0=ignore name associations

onWindows = sys.platform[:3] == 'win'

def launchUnixBrowser(url, verbose=True): # add your platform if unique

tries = ['netscape', 'mosaic', 'lynx'] # order your preferences here

tries = ['firefox'] + tries # Firefox rules!

for program in tries:

if which(program): break # find one that is on $path

else:

assert 0, 'Sorry - no browser found'

if verbose: print 'Running', program

os.system('%s %s &' % (program, url)) # or fork+exec; assumes $path

def launchWindowsBrowser(url, verbose=True):

if useWinStart and len(url) <= 400: # on Windows: start or spawnv

try: # spawnv works if cmd too long

if verbose: print 'Starting'

os.system('start ' + url) # try name associations first

return # fails if cmdline too long

except: pass

browser = None # search for a browser exe

tries = ['IEXPLORE.EXE', 'netscape.exe'] # try Explorer, then Netscape

tries = ['firefox.exe'] + tries

for program in tries:

browser = which(program) or guessLocation(program, 1)

if browser: break

assert browser != None, 'Sorry - no browser found'

if verbose: print 'Spawning', browser

os.spawnv(os.P_DETACH, browser, (program, url))

def launchBrowser(Mode='-file', Page='index.html', Site=None, verbose=True):

if Mode == '-live':

url = 'http://%s/%s' % (Site, Page) # open page at remote site

else:

url = 'file://%s' % Page # open page on this machine

if verbose: print 'Opening', url

if onWindows:

launchWindowsBrowser(url, verbose) # use windows start, spawnv

else:

launchUnixBrowser(url, verbose) # assume $path on Unix, Linux

if _ _name_ _ == '_ _main_ _':

# defaults

Mode = '-file'

Page = os.getcwd( ) + '/Internet/Web/PyInternetDemos.html'

Site = 'starship.python.net/~lutz'

# get command-line args

helptext = "Usage: LaunchBrowser.py [ -file path | -live path site ]"

argc = len(sys.argv)

if argc > 1: Mode = sys.argv[1]

if argc > 2: Page = sys.argv[2]

if argc > 3: Site = sys.argv[3]

if Mode not in ['-live', '-file']:

print helptext

sys.exit(1)

else:

launchBrowser(Mode, Page, Site)This module is designed to be both run and imported.

When run by itself on my Windows machine, Firefox starts up. The

requested page file is always displayed in a new browser window

when os.spawnv is applied but

in the currently open browser window (if any) when running a

start command:

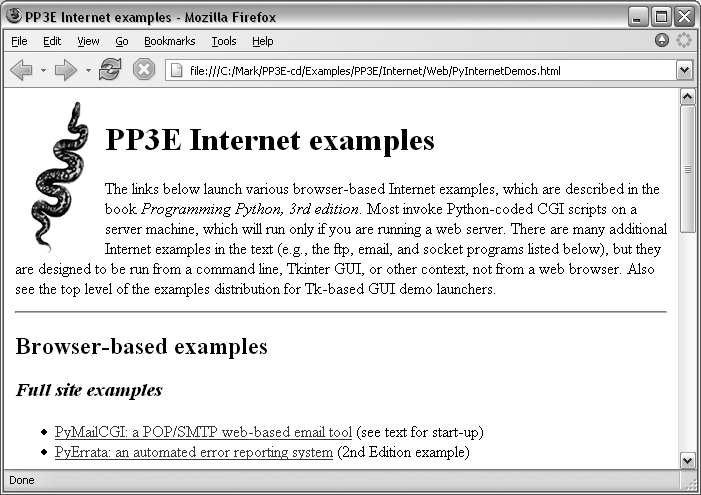

C:...PP3E>LaunchBrowser.py

Opening file://C:MarkPP3E-cdExamplesPP3E/Internet/Web/PyInternetDemos.html

StartingThe seemingly odd mix of forward and backward slashes in the URL here works fine within the browser; it pops up the window shown in Figure 6-2. Note that this script may be renamed with a .pyw extension by the time you fetch its source in order to suppress its pop-up window on Windows; rename back to a .py to see its trace outputs.

By default, a start

command is spawned; to see the browser search procedure in action

on Windows, set the script’s useWinStart variable to False (or 0). The script will search for a browser

on your PATH settings, and then

search in common Windows install directories hardcoded in

Launcher.py. Here is the search in action on

an older machine with Internet Explorer as the first in the list

of browsers to try (the PATH on

my newer machine is too complex to bear):

C:...PP3E>python LaunchBrowser.py-file C:StuffWebsitepublic_htmlabout-pp.htmlOpening file://C:StuffWebsitepublic_htmlabout-pp.html Looking for IEXPLORE.EXE on ['C:\WINDOWS', 'C:\WINDOWS', 'C:\WINDOWS\COMMAND', 'C:\STUFF\BIN.MKS', 'C:\PROGRAM FILES\PYTHON'] Not at C:WINDOWSIEXPLORE.EXE Not at C:WINDOWSIEXPLORE.EXE Not at C:WINDOWSCOMMANDIEXPLORE.EXE Not at C:STUFFBIN.MKSIEXPLORE.EXE Not at C:PROGRAM FILESPYTHONIEXPLORE.EXE IEXPLORE.EXE not on system path Searching for IEXPLORE.EXE in C:Program FilesPython Searching for IEXPLORE.EXE in C:PP3rdEdexamplesPP3E Searching for IEXPLORE.EXE in C:Program Files Spawning C:Program FilesInternet ExplorerIEXPLORE.EXE

If you study these trace message you’ll notice that the

browser wasn’t on the system search path but was eventually

located in a local C:Program Files

subdirectory; this is just the Launcher module’s which and guessLocation functions at work. As run

here, the script searches for Internet Explorer first; if that’s

not to your liking, try changing the script’s tries list to make Netscape (or Firefox)

first:

C:...PP3E>python LaunchBrowser.py

Opening file://C:PP3rdEdexamplesPP3E/Internet/Cgi-Web/PyInternetDemos.html

Looking for netscape.exe on ['C:\WINDOWS', 'C:\WINDOWS',

'C:\WINDOWS\COMMAND', 'C:\STUFF\BIN.MKS', 'C:\PROGRAM FILES\PYTHON']

Not at C:WINDOWS

etscape.exe

Not at C:WINDOWS

etscape.exe

Not at C:WINDOWSCOMMAND

etscape.exe

Not at C:STUFFBIN.MKS

etscape.exe

Not at C:PROGRAM FILESPYTHON

etscape.exe

netscape.exe not on system path

Searching for netscape.exe in C:Program FilesPython

Searching for netscape.exe in C:PP3rdEdexamplesPP3E

Searching for netscape.exe in C:Program Files

Spawning C:Program FilesNetscapeCommunicatorProgram

etscape.exeHere, the script eventually found Netscape in a different

install directory on the local machine. Besides automatically

finding a user’s browser for him, this script also aims to be

portable. When running this file unchanged on Linux, the local

Netscape browser starts if it lives on your PATH; otherwise, others are

tried:

[mark@toy ~/PP3rdEd/examples/PP3E]$python LaunchBrowser.py

Opening file:///home/mark/PP3rdEd/examples/PP3E/Internet/Cgi-

Web/PyInternetDemos.html

Looking for netscape on ['/home/mark/bin', '.', '/usr/bin', '/usr/bin',

'/usr/local/bin', '/usr/X11R6/bin', '/bin', '/usr/X11R6/bin', '/home/mark/

bin', '/usr/X11R6/bin', '/home/mark/bin', '/usr/X11R6/bin']

Not at /home/mark/bin/netscape

Not at ./netscape

Found /usr/bin/netscape

Running netscape

[mark@toy ~/PP3rdEd/examples/PP3E]$If you have an Internet connection, you can open pages at remote servers too—the next command opens the root page at my site on the starship.python.net server, located somewhere on the East Coast the last time I checked:

C:...PP3E>python LaunchBrowser.py -live ~lutz starship.python.net

Opening http://starship.python.net/~lutz

StartingIn Chapter 10, we’ll see that this script is also run to start Internet examples in the top-level demo launcher system: the PyDemos script presented in that chapter portably opens local or remote web page files with this button-press callback:

[File mode]

pagepath = os.getcwd( ) + '/Internet/Web'

demoButton('PyMailCGI2',

'Browser-based pop/smtp email interface',

'LaunchBrowser.pyw -file %s/PyMailCgi/pymailcgi.html' % pagepath,

pymailcgifiles)

[Live mode]

site = 'localhost:%s'

demoButton('PyMailCGI2',

'Browser-based pop/smtp email interface',

'LaunchBrowser.pyw -live pymailcgi.html '+ (site % 8000),

pymailcgifiles)Other programs can spawn

LaunchBrowser.py command lines such as those

shown previously with tools such as os.system, as usual; but since the

script’s core logic is coded in a function, it can just as easily

be imported and called:

>>>from PP3E.LaunchBrowser import launchBrowser>>>launchBrowser(Page=r'C:MarkWEBSITEpublic_htmlabout-pp.html')Opening file://C:MarkWEBSITEpublic_htmlabout-pp.html Starting >>>

When called like this, launchBrowser isn’t much different than

spawning a start command on DOS

or a netscape command on Linux,

but the Python launchBrowser

function is designed to be a portable interface for browser

startup across platforms. Python scripts can use this interface to

pop up local HTML documents in web browsers; on machines with live

Internet links, this call even lets scripts open browsers on

remote pages on the Web:

>>>launchBrowser(Mode='-live', Page='index.html', Site='www.python.org')Opening http://www.python.org/index.html Starting >>>launchBrowser(Mode='-live', Page='PyInternetDemos.html',...Site='localhost')Opening http://localhost/PyInternetDemos.html Starting

On a computer where there is just a dial-up connection, the first call here opens a new Internet Explorer GUI window if needed, dials out through a modem, and fetches the Python home page from http://www.python.org on both Windows and Linux—not bad for a single function call. On broadband connections, the page comes up directly. The second call does the same but, using a locally running web server, opens a web demos page we’ll explore in Chapter 16.

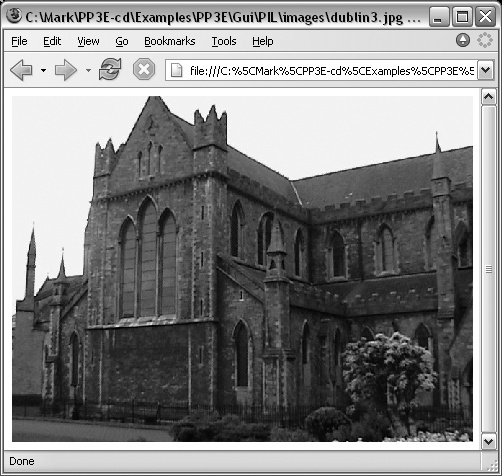

I mentioned earlier that browsers are a cheap way to present multimedia. Alas, this sort of thing is best viewed live, so the best I can do is show startup commands here. The next command line and function call, for example, display two GIF images in Internet Explorer on my machine (be sure to use full local pathnames). The result of the first of these is captured in Figure 6-3 (you may have to edit the browser tries list and start-mode flags on your machine to make this work).

C:...PP3E>python LaunchBrowser.py-file C:MarkPP3E-cdExamplesPP3EGuiPILimagesdublin3.jpgC: emp>python>>>from LaunchBrowser import launchBrowser>>>launchBrowser(Page=r'C: empExamplesPP3EGuigifsmp_lumberjack.gif')

The next command line and call open the sousa.au audio file on my machine; the second of these downloads the file from http://www.rmi.net first. If all goes as planned, the Monty Python theme song should play on your computer:

C:PP3rdEdexamples>python LaunchBrowser.py-file C:MarkPP3E-cdExamplesPP3EInternetFtpsousa.auOpening file://C:PP3E-cdExamplesPP3EInternetFtpsousa.au Starting >>>launchBrowser(Mode='-live',...Site='www.rmi.net',...Page='~lutz/sousa.au',...verbose=0)>>>

Of course, you could just pass these filenames to a spawned

start command or os.startfile call on Windows, or run the

appropriate handler program directly with something like os.system. But opening these files in a

browser is a more portable approach; you don’t need to keep track

of a set of file-handler programs per platform. Provided your

scripts use a portable browser launcher such as LaunchBrowser, you don’t even need to

keep track of a browser per platform.

That generality is a win unless you wish to do something more specific for certain media types or can’t run a web browser. On some PDAs, for instance, you may not be able to open a general web browser on a particular file. In the next section, we’ll see how to get more specific when we need to.

Finally, I want to point out that LaunchBrowser reflects browsers that I

tend to use. For instance, it tries to find Firefox and then

Internet Explorer before Netscape on Windows, and prefers Netscape

over Mosaic and Lynx on Linux, but you should feel free to change

these choices in your copy of the script. In fact, both LaunchBrowser and Launcher make a few heuristic guesses

when searching for files that may not make sense on every

computer. Configure as needed.

Reptilian minds think alike. Roughly one year after I

wrote the LaunchBrowser script of

the prior section for the second edition of this book, Python

sprouted a new standard library module that serves a similar

purpose: webbrowser. In this section, we wrap up the chapter with a script

that makes use of this new module as well as the Python mimetypes module in order to implement a

generic, portable, and extendable media file player.

Like LaunchBrowser of the prior section, the

standard library webbrowser

module also attempts to provide a portable interface for launching

browsers from scripts. Its implementation is more complex but

likely to support more options and platforms than the LaunchBrowser script presented earlier

(classic Macintosh browsers, for instance, are directly supported

as well). Its interface is straightforward:

import webbrowser

webbrowser.open_new('file://' + fullfilename) # or http://...The preceding code will open the named file in a new web

browser window using whatever browser is found on the underlying

computer or raise an exception if it cannot. Use the module’s

open call to reuse an

already-open browser window if possible, and use an argument

string of the form “http://...” to open a page on a web server. In

fact, you can pass in any URL that the browser understands. The

following pops up Python’s home page in a new browser window, for

example:

>>> webbrowser.open_new('http://www.python.org')Among other things, this is an easy way to display HTML

documents as well as media files, as shown in the prior section.

We’ll use this module later in this book as a way to display

HTML-formatted email messages in the PyMailGUI program in Chapter 15. See the Python library

manual for more details. In Chapter

16, we’ll also meet a related call, urllib.urlopen, which fetches a web

page’s text but does not open it in a browser.

To demonstrate the webbrowser module’s basic utility,

though, let’s code another way to open multimedia files. Example 6-16 tries to open a

media file on your computer in a somewhat more intelligent way. As

a last resort, it always falls back on trying to open the file in

a web browser, much like we did in the prior section. Here,

though, we first try to run a type-specific player if one is

specific in tables, and we use the Python standard library’s

webbrowser to open a browser

instead of using our LaunchBrowser.

To make this even more useful, we also use the

Python mimetypes standard

library module to automatically determine the media type from the

filename. We get back a type/subtype MIME content-type string if

the type can be determined or None if the guess failed:

>>>import mimetypes>>>mimetypes.guess_type('spam.jpg')('image/jpeg', None) >>>mimetypes.guess_type('TheBrightSideOfLife.mp3')('audio/mpeg', None) >>>mimetypes.guess_type('lifeofbrian.mpg')('video/mpeg', None) >>>mimetypes.guess_type('lifeofbrian.xyz')# unknown type (None, None)

Stripping off the first part of the content-type string gives the file’s general media type, which we can use to select a generic player:

>>>contype, encoding = mimetypes.guess_type('spam.jpg')>>>contype.split('/')[0]'image'

A subtle thing: the second item in the tuple returned from

the mimetypes guess is an

encoding type we won’t use here for opening purposes. We still

have to pay attention to it, though—if it is not None, it means the file is compressed

(gzip or compress), even if we receive a media

content type. For example, if the filename is something like

spam.gif.gz, it’s a compressed image that we

don’t want to try to open directly:

>>>mimetypes.guess_type('spam.gz')# content unknown (None, 'gzip') >>>mimetypes.guess_type('spam.gif.gz')# don't play me! ('image/gif', 'gzip') >>>mimetypes.guess_type('spam.zip')# skip archives ('application/zip', None)

This module is even smart enough to give us a filename extension for a type:

>>>mimetypes.guess_type('sousa.au')('audio/basic', None) >>>mimetypes.guess_extension('audio/basic')'.au'

We’ll use the mimetypes

module again in FTP examples in Chapter 14 to determine transfer

type (text or binary), and in our email examples in Chapters 14 and 15 to send, save, and open mail

attachments.

In Example 6-16,

we use mimetypes to select a

table of platform-specific player commands for the media type of

the file to be played. That is, we pick a player table for the

file’s media type, and then pick a command from the player table

for the platform. At each step, we give up and run a web browser

if there is nothing more specific to be done. The end result is a

general and smarter media player tool that you can extend as

needed. It will be as portable and specific as the tables you

provide to it.

Example 6-16. PP3ESystemMediaplayfile.py

#!/usr/local/bin/python

################################################################################

# Try to play an arbitrary media file. This may not work on your system as is;

# audio files use filters and command lines on Unix, and filename associations

# on Windows via the start command (i.e., whatever you have on your machine to

# run .au files--an audio player, or perhaps a web browser). Configure and

# extend as needed. As a last resort, always tries to launch a web browser with

# Python webbrowser module (like LaunchBrowser.py). See also: Lib/audiodev.py.

# playknownfile assumes you know what sort of media you wish to open; playfile

# tries to determine media type automatically using Python mimetypes module.

################################################################################

import os, sys

helpmsg = """

Sorry: can't find a media player for '%s' on your system!

Add an entry for your system to the media player dictionary

for this type of file in playfile.py, or play the file manually.

"""

def trace(*args):

print ' '.join(args) # with spaces between

################################################################################

# player techniques: generic and otherwise: extend me

################################################################################

class MediaTool:

def _ _init_ _(self, runtext=''):

self.runtext = runtext

class Filter(MediaTool):

def run(self, mediafile, **options):

media = open(mediafile, 'rb')

player = os.popen(self.runtext, 'w') # spawn shell tool

player.write(media.read( )) # send to its stdin

class Cmdline(MediaTool):

def run(self, mediafile, **options):

cmdline = self.runtext % mediafile # run any cmd line

os.system(cmdline) # use %s for filename

class Winstart(MediaTool): # use Windows registry

def run(self, mediafile, wait=False): # or os.system('start file')

if not wait: # allow wait for curr media

os.startfile(mediafile)

else:

os.system('start /WAIT ' + mediafile)

class Webbrowser(MediaTool):

def run(self, mediafile, **options): # open in web browser

import webbrowser # find browser, no wait

fullpath = os.path.abspath(mediafile) # file:// needs abs dir

webbrowser.open_new('file://%s' % fullpath) # open media file

################################################################################

# media- and platform-specific policies: change me, or pass one in

##############################################################################

# map platform to player: change me!

audiotools = {

'sunos5': Filter('/usr/bin/audioplay'), # os.popen().write( )

'linux2': Cmdline('cat %s > /dev/audio'), # on zaurus, at least

'sunos4': Filter('/usr/demo/SOUND/play'),

'win32': Winstart( ) # startfile or system

#'win32': Cmdline('start %s')

}

videotools = {

'linux2': Cmdline('tkcVideo_c700 %s'), # zaurus pda

'win32': Winstart( ), # avoid DOS pop up

}

imagetools = {

'linux2': Cmdline('zimager %s/%%s' % os.getcwd( )), # zaurus pda

'win32': Winstart( ),

}

# map mimetype of filenames to player tables

mimetable = {'audio': audiotools, # add text: PyEdit?

'video': videotools,

'image': imagetools}

################################################################################

# top-level interfaces

################################################################################

def trywebbrowser(mediafile, helpmsg=helpmsg):

"""

try to open a file in a web browser

"""

trace('trying browser', mediafile) # last resort

try:

player = Webbrowser( )

player.run(mediafile)

except:

print helpmsg % mediafile # nothing worked

def playknownfile(mediafile, playertable={}, **options):

"""

play media file of known type: uses platform-specific

player objects, or spawns a web browser if nothing for

this platform; pass in a media-specific player table

"""

if sys.platform in playertable:

playertable[sys.platform].run(mediafile, **options) # specific tool

else:

trywebbrowser(mediafile) # general scheme

def playfile(mediafile, mimetable=mimetable, **options):

"""

play media file of any type: uses mimetypes to guess

media type and map to platform-specific player tables;

spawn web browser if media type unknown, or has no table

"""

import mimetypes

(contenttype, encoding) = mimetypes.guess_type(mediafile) # check name

if contenttype == None or encoding is not None: # can't guess

contenttype = '?/?' # poss .txt.gz

maintype, subtype = contenttype.split('/', 1) # 'image/jpeg'

if maintype in mimetable:

playknownfile(mediafile, mimetable[maintype], **options) # try table

else:

trywebbrowser(mediafile) # other types

###############################################################################

# self-test code

###############################################################################

if _ _name_ _ == '_ _main_ _':

# media type known

playknownfile('sousa.au', audiotools, wait=True)

playknownfile('ora-pp2e.jpg', imagetools, wait=True)

playknownfile('mov10428.mpg', videotools, wait=True)

playknownfile('img_0276.jpg', imagetools)

playknownfile('mov10510.mpg', mimetable['video'])

# media type guessed

raw_input('Stop players and press Enter')

playfile('sousa.au', wait=True) # default mimetable

playfile('img_0268.jpg')

playfile('mov10428.mpg' , mimetable) # no extra options

playfile('calendar.html') # default web browser

playfile('wordfile.doc')

raw_input('Done') # stay open if clickedOne coding note: we could also write the playknownfile function the following way

(this form is more concise, but some future readers of our code

might make the case that it is also less explicit and hence less

understandable, especially if we code the same way in playfile with an empty table

default):

defaultplayer = Webbrowser( ) player = playertable.get(sys.platform, defaultplayer) player.run(mediafile, **options)

Study this script’s code and run it on your own computer to see what happens. As usual, you can test it interactively (use the package path to import from a different directory):

>>>from PP3E.System.Media.playfile import playfile>>>playfile('mov10428.mpg')

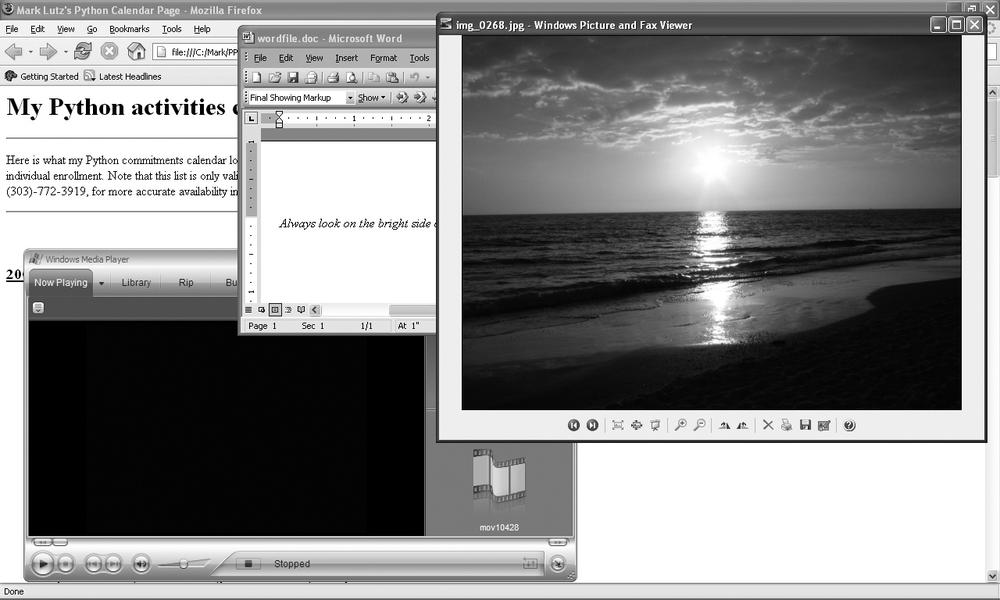

We’ll use this example again as an imported library like this in Chapter 14 to open media files downloaded by FTP. When the script file is run directly, if all goes well, its self-test code at the end opens a number of audio, image, and video files located in the script’s directory, using either platform-specific players or a general web browser on your machine. Just for fun, it also opens an HTML file and a Word document to test the web browser code. As is, its player tables are only populated with commands for the machines on which I tested it:

On my Windows XP computer, the script opens audio and video files in Windows Media Player, images in the Windows standard picture viewer, HTML files in the Firefox web browser, and Word documents in Microsoft Word (more on this in the

webbrowsersidebar). This may vary on your machine; Windows ultimately decides which player to run based on what you have registered to open a filename extension. We also wait for some files to play or the viewer to be closed before starting another; Media Player versions 7 and later cannot open multiple instances of the Player and so can handle only one file at a time.My Linux test machine for this script was a Zaurus PDA; on that platform, this script opens image and audio files in machine-specific programs, runs audio files by sending them to the

/dev/audiodevice file, and fails on the HTML file (it’s not yet configured to use Netfront). On a Zaurus, the script runs command lines, and always pauses until a viewer is closed.

Figure 6-4 shows the script’s handiwork on Windows. For other platforms and machines, you will likely have to extend the player dictionaries with platform-specific entries, within this file, or by assigning from outside:

import playfile

playfile.audiotools['platformX'] = playfile.Cmdline('...')

playfile.mimetable['newstuff'] = {...}Or you can pass your own player table to the playfile function:

from playfile import playfile

myplayers = {...} # or start with mimetools.copy( )

playfile('Nautyus_Maximus.xyz', myplayers)The MediaTool classes in

this file provide general ways to open files, but you may also

need to subclass to customize for unique cases. This script also

assumes the media file is located on the local machine (even

though the webbrowser module

supports remote files with “http://” names), and it does not

currently allow different players for different MIME subtypes (you

may want to handle both “text/plain” and “text/xml”

differently).

In fact, this script is really just something of a simple framework that was designed to be extended. As always, hack on; this is Python, after all.

[*] You gurus and wizards out there will just have to take my word for it. One of the very first things you learn from flying around the world teaching Python to beginners is just how much knowledge developers take for granted. In the first edition of the book Learning Python, for example, my coauthor and I directed readers to do things like “open a file in your favorite text editor” and “start up a DOS command console.” We had no shortage of email from beginners wondering what in the world we meant.

[*] For example, the PyDemos demo bar GUI we’ll meet in Chapter 10 has buttons that automatically open a browser on web pages related to this book—the publisher’s site, the Python home page, my update files, and so on—when clicked.