The basic characteristics of an investment portfolio are usually determined by the position and characteristics of the owner or owners. At one extreme we have had savings banks, life-insurance companies, and so-called legal trust funds. A generation ago their investments were limited by law in many states to high-grade bonds and, in some cases, high-grade preferred stocks. At the other extreme we have the well-to-do and experienced businessman, who will include any kind of bond or stock in his security list provided he considers it an attractive purchase.

It has been an old and sound principle that those who cannot afford to take risks should be content with a relatively low return on their invested funds. From this there has developed the general notion that the rate of return which the investor should aim for is more or less proportionate to the degree of risk he is ready to run. Our view is different. The rate of return sought should be dependent, rather, on the amount of intelligent effort the investor is willing and able to bring to bear on his task. The minimum return goes to our passive investor, who wants both safety and freedom from concern. The maximum return would be realized by the alert and enterprising investor who exercises maximum intelligence and skill. In 1965 we added: “In many cases there may be less real risk associated with buying a ‘bargain issue’ offering the chance of a large profit than with a conventional bond purchase yielding about 4½%.” This statement had more truth in it than we ourselves suspected, since in subsequent years even the best long-term bonds lost a substantial part of their market value because of the rise in interest rates.

The Basic Problem of Bond-Stock Allocation

We have already outlined in briefest form the portfolio policy of the defensive investor.* He should divide his funds between high-grade bonds and high-grade common stocks.

We have suggested as a fundamental guiding rule that the investor should never have less than 25% or more than 75% of his funds in common stocks, with a consequent inverse range of between 75% and 25% in bonds. There is an implication here that the standard division should be an equal one, or 50–50, between the two major investment mediums. According to tradition the sound reason for increasing the percentage in common stocks would be the appearance of the “bargain price” levels created in a protracted bear market. Conversely, sound procedure would call for reducing the common-stock component below 50% when in the judgment of the investor the market level has become dangerously high.

These copybook maxims have always been easy to enunciate and always difficult to follow—because they go against that very human nature which produces that excesses of bull and bear markets. It is almost a contradiction in terms to suggest as a feasible policy for the average stockowner that he lighten his holdings when the market advances beyond a certain point and add to them after a corresponding decline. It is because the average man operates, and apparently must operate, in opposite fashion that we have had the great advances and collapses of the past; and—this writer believes—we are likely to have them in the future.

If the division between investment and speculative operations were as clear now as once it was, we might be able to envisage investors as a shrewd, experienced group who sell out to the heedless, hapless speculators at high prices and buy back from them at depressed levels. This picture may have had some verisimilitude in bygone days, but it is hard to identify it with financial developments since 1949. There is no indication that such professional operations as those of the mutual funds have been conducted in this fashion. The percentage of the portfolio held in equities by the two major types of funds—“balanced” and “common-stock”—has changed very little from year to year. Their selling activities have been largely related to endeavors to switch from less to more promising holdings.

If, as we have long believed, the stock market has lost contact with its old bounds, and if new ones have not yet been established, then we can give the investor no reliable rules by which to reduce his common-stock holdings toward the 25% minimum and rebuild them later to the 75% maximum. We can urge that in general the investor should not have more than one-half in equities unless he has strong confidence in the soundness of his stock position and is sure that he could view a market decline of the 1969–70 type with equanimity. It is hard for us to see how such strong confidence can be justified at the levels existing in early 1972. Thus we would counsel against a greater than 50% apportionment to common stocks at this time. But, for complementary reasons, it is almost equally difficult to advise a reduction of the figure well below 50%, unless the investor is disquieted in his own mind about the current market level, and will be satisfied also to limit his participation in any further rise to, say, 25% of his total funds.

We are thus led to put forward for most of our readers what may appear to be an oversimplified 50–50 formula. Under this plan the guiding rule is to maintain as nearly as practicable an equal division between bond and stock holdings. When changes in the market level have raised the common-stock component to, say, 55%, the balance would be restored by a sale of one-eleventh of the stock portfolio and the transfer of the proceeds to bonds. Conversely, a fall in the common-stock proportion to 45% would call for the use of one-eleventh of the bond fund to buy additional equities.

Yale University followed a somewhat similar plan for a number of years after 1937, but it was geared around a 35% “normal holding” in common stocks. In the early 1950s, however, Yale seems to have given up its once famous formula, and in 1969 held 61% of its portfolio in equities (including some convertibles). (At that time the endowment funds of 71 such institutions, totaling $7.6 billion, held 60.3% in common stocks.) The Yale example illustrates the almost lethal effect of the great market advance upon the once popular formula approach to investment. Nonetheless we are convinced that our 50–50 version of this approach makes good sense for the defensive investor. It is extremely simple; it aims unquestionably in the right direction; it gives the follower the feeling that he is at least making some moves in response to market developments; most important of all, it will restrain him from being drawn more and more heavily into common stocks as the market rises to more and more dangerous heights.

Furthermore, a truly conservative investor will be satisfied with the gains shown on half his portfolio in a rising market, while in a severe decline he may derive much solace from reflecting how much better off he is than many of his more venturesome friends.

While our proposed 50–50 division is undoubtedly the simplest “all-purpose program” devisable, it may not turn out to be the best in terms of results achieved. (Of course, no approach, mechanical or otherwise, can be advanced with any assurance that it will work out better than another.) The much larger income return now offered by good bonds than by representative stocks is a potent argument for favoring the bond component. The investor’s choice between 50% or a lower figure in stocks may well rest mainly on his own temperament and attitude. If he can act as a cold-blooded weigher of the odds, he would be likely to favor the low 25% stock component at this time, with the idea of waiting until the DJIA dividend yield was, say, two-thirds of the bond yield before he would establish his median 50–50 division between bonds and stocks. Starting from 900 for the DJIA and dividends of $36 on the unit, this would require either a fall in taxable bond yields from 7½% to about 5.5% without any change in the present return on leading stocks, or a fall in the DJIA to as low as 660 if there is no reduction in bond yields and no increase in dividends. A combination of intermediate changes could produce the same “buying point.” A program of that kind is not especially complicated; the hard part is to adopt it and to stick to it not to mention the possibility that it may turn out to have been much too conservative.

The Bond Component

The choice of issues in the bond component of the investor’s portfolio will turn about two main questions: Should he buy taxable or tax-free bonds, and should he buy shorter- or longer-term maturities? The tax decision should be mainly a matter of arithmetic, turning on the difference in yields as compared with the investor’s tax bracket. In January 1972 the choice in 20-year maturities was between obtaining, say, 7½% on “grade Aa” corporate bonds and 5.3% on prime tax-free issues. (The term “municipals” is generally applied to all species of tax-exempt bonds, including state obligations.) There was thus for this maturity a loss in income of some 30% in passing from the corporate to the municipal field. Hence if the investor was in a maximum tax bracket higher than 30% he would have a net saving after taxes by choosing the municipal bonds; the opposite, if his maximum tax was less than 30%. A single person starts paying a 30% rate when his income after deductions passes $10,000; for a married couple the rate applies when combined taxable income passes $20,000. It is evident that a large proportion of individual investors would obtain a higher return after taxes from good municipals than from good corporate bonds.

The choice of longer versus shorter maturities involves quite a different question, viz.: Does the investor want to assure himself against a decline in the price of his bonds, but at the cost of (1) a lower annual yield and (2) loss of the possibility of an appreciable gain in principal value? We think it best to discuss this question in Chapter 8, The Investor and Market Fluctuations.

For a period of many years in the past the only sensible bond purchases for individuals were the U.S. savings issues. Their safety was—and is—unquestioned; they gave a higher return than other bond investments of first quality; they had a money-back option and other privileges which added greatly to their attractiveness. In our earlier editions we had an entire chapter entitled “U.S. Savings Bonds: A Boon to Investors.”

As we shall point out, U.S. savings bonds still possess certain unique merits that make them a suitable purchase by any individual investor. For the man of modest capital—with, say, not more than $10,000 to put into bonds—we think they are still the easiest and the best choice. But those with larger funds may find other mediums more desirable.

Let us list a few major types of bonds that deserve investor consideration, and discuss them briefly with respect to general description, safety, yield, market price, risk, income-tax status, and other features.

1. U.S. SAVINGS BONDS, SERIES E AND SERIES H. We shall first summarize their important provisions, and then discuss briefly the numerous advantages of these unique, attractive, and exceedingly convenient investments. The Series H bonds pay interest semi-annually, as do other bonds. The rate is 4.29% for the first year, and then a flat 5.10% for the next nine years to maturity. Interest on the Series E bonds is not paid out, but accrues to the holder through increase in redemption value. The bonds are sold at 75% of their face value, and mature at 100% in 5 years 10 months after purchase. If held to maturity the yield works out at 5%, compounded semi-annually. If redeemed earlier, the yield moves up from a minimum of 4.01% in the first year to an average of 5.20% in the next 45/6 years.

Interest on the bonds is subject to Federal income tax, but is exempt from state income tax. However, Federal income tax on the Series E bonds may be paid at the holder’s option either annually as the interest accrues (through higher redemption value), or not until the bond is actually disposed of.

Owners of Series E bonds may cash them in at any time (shortly after purchase) at their current redemption value. Holders of Series H bonds have similar rights to cash them in at par value (cost). Series E bonds are exchangeable for Series H bonds, with certain tax advantages. Bonds lost, destroyed, or stolen may be replaced without cost. There are limitations on annual purchases, but liberal provisions for co-ownership by family members make it possible for most investors to buy as many as they can afford. Comment: There is no other investment that combines (1) absolute assurance of principal and interest payments, (2) the right to demand full “money back” at any time, and (3) guarantee of at least a 5% interest rate for at least ten years. Holders of the earlier issues of Series E bonds have had the right to extend their bonds at maturity, and thus to continue to accumulate annual values at successively higher rates. The deferral of income-tax payments over these long periods has been of great dollar advantage; we calculate it has increased the effective net-after-tax rate received by as much as a third in typical cases. Conversely, the right to cash in the bonds at cost price or better has given the purchasers in former years of low interest rates complete protection against the shrinkage in principal value that befell many bond investors; otherwise stated, it gave them the possibility of benefiting from the rise in interest rates by switching their low-interest holdings into very-high-coupon issues on an even-money basis.

In our view the special advantages enjoyed by owners of savings bonds now will more than compensate for their lower current return as compared with other direct government obligations.

2. OTHER UNITED STATES BONDS. A profusion of these issues exists, covering a wide variety of coupon rates and maturity dates. All of them are completely safe with respect to payment of interest and principal. They are subject to Federal income taxes but free from state income tax. In late 1971 the long-term issues—over ten years—showed an average yield of 6.09%, intermediate issues (three to five years) returned 6.35%, and short issues returned 6.03%.

In 1970 it was possible to buy a number of old issues at large discounts. Some of these are accepted at par in settlement of estate taxes. Example: The U.S. Treasury 3½s due 1990 are in this category; they sold at 60 in 1970, but closed 1970 above 77.

It is interesting to note also that in many cases the indirect obligations of the U.S. government yield appreciably more than its direct obligations of the same maturity. As we write, an offering appears of 7.05% of “Certificates Fully Guaranteed by the Secretary of Transportation of the Department of Transportation of the United States.” The yield was fully 1% more than that on direct obligations of the U.S., maturing the same year (1986). The certificates were actually issued in the name of the Trustees of the Penn Central Transportation Co., but they were sold on the basis of a statement by the U.S. Attorney General that the guarantee “brings into being a general obligation of the United States, backed by its full faith and credit.” Quite a number of indirect obligations of this sort have been assumed by the U.S. government in the past, and all of them have been scrupulously honored.

The reader may wonder why all this hocus-pocus, involving an apparently “personal guarantee” by our Secretary of Transportation, and a higher cost to the taxpayer in the end. The chief reason for the indirection has been the debt limit imposed on government borrowing by the Congress. Apparently guarantees by the government are not regarded as debts—a semantic windfall for shrewder investors. Perhaps the chief impact of this situation has been the creation of tax-free Housing Authority bonds, enjoying the equivalent of a U.S. guarantee, and virtually the only tax-exempt issues that are equivalent to government bonds. Another type of government-backed issues is the recently created New Community Debentures, offered to yield 7.60% in September 1971.

3. STATE AND MUNICIPAL BONDS. These enjoy exemption from Federal income tax. They are also ordinarily free of income tax in the state of issue but not elsewhere. They are either direct obligations of a state or subdivision, or “revenue bonds” dependent for interest payments on receipts from a toll road, bridge, building lease, etc. Not all tax-free bonds are strongly enough protected to justify their purchase by a defensive investor. He may be guided in his selection by the rating given to each issue by Moody’s or Standard & Poor’s. One of three highest ratings by both services—Aaa (AAA), Aa (AA), or A—should constitute a sufficient indication of adequate safety. The yield on these bonds will vary both with the quality and the maturity, with the shorter maturities giving the lower return. In late 1971 the issues represented in Standard & Poor’s municipal bond index averaged AA in quality rating, 20 years in maturity, and 5.78% in yield. A typical offering of Vineland, N.J., bonds, rated AA for A and gave a yield of only 3% on the one-year maturity, rising to 5.8% to the 1995 and 1996 maturities.1

4. CORPORATION BONDS. These bonds are subject to both Federal and state tax. In early 1972 those of highest quality yielded 7.19% for a 25-year maturity, as reflected in the published yield of Moody’s Aaa corporate bond index. The so-called lower-medium-grade issues—rated Baa—returned 8.23% for long maturities. In each class shorter-term issues would yield somewhat less than longer-term obligations.

Comment. The above summaries indicate that the average investor has several choices among high-grade bonds. Those in high income-tax brackets can undoubtedly obtain a better net yield from good tax-free issues than from taxable ones. For others the early 1972 range of taxable yield would seem to be from 5.00% on U.S. savings bonds, with their special options, to about 7½% on high-grade corporate issues.

Higher-Yielding Bond Investments

By sacrificing quality an investor can obtain a higher income return from his bonds. Long experience has demonstrated that the ordinary investor is wiser to keep away from such high-yield bonds. While, taken as a whole, they may work out somewhat better in terms of overall return than the first-quality issues, they expose the owner to too many individual risks of untoward developments, ranging from disquieting price declines to actual default. (It is true that bargain opportunities occur fairly often in lower-grade bonds, but these require special study and skill to exploit successfully.)*

Perhaps we should add here that the limits imposed by Congress on direct bond issues of the United States have produced at least two sorts of “bargain opportunities” for investors in the purchase of government-backed obligations. One is provided by the tax-exempt “New Housing” issues, and the other by the recently created (taxable) “New Community debentures.” An offering of New Housing issues in July 1971 yielded as high as 5.8%, free from both Federal and state taxes, while an issue of (taxable) New Community debentures sold in September 1971 yielded 7.60%. Both obligations have the “full faith and credit” of the United States government behind them and hence are safe without question. And—on a net basis—they yield considerably more than ordinary United States bonds.†

Savings Deposits in Lieu of Bonds

An investor may now obtain as high an interest rate from a savings deposit in a commercial or savings bank (or from a bank certificate of deposit) as he can from a first-grade bond of short maturity. The interest rate on bank savings accounts may be lowered in the future, but under present conditions they are a suitable substitute for short-term bond investment by the individual.

Convertible Issues

These are discussed in Chapter 16. The price variability of bonds in general is treated in Chapter 8, The Investor and Market Fluctuations.

Call Provisions

In previous editions we had a fairly long discussion of this aspect of bond financing, because it involved a serious but little noticed injustice to the investor. In the typical case bonds were callable fairly soon after issuance, and at modest premiums—say 5%—above the issue price. This meant that during a period of wide fluctuations in the underlying interest rates the investor had to bear the full brunt of unfavorable changes and was deprived of all but a meager participation in favorable ones.

EXAMPLE: Our standard example has been the issue of American Gas & Electric 100-year 5% debentures, sold to the public at 101 in 1928. Four years later, under near-panic conditions, the price of these good bonds fell to 62½, yielding 8%. By 1946, in a great reversal, bonds of this type could be sold to yield only 3%, and the 5% issue should have been quoted at close to 160. But at that point the company took advantage of the call provision and redeemed the issue at a mere 106.

The call feature in these bond contracts was a thinly disguised instance of “heads I win, tails you lose.” At long last, the bond-buying institutions refused to accept this unfair arrangement; in recent years most long-term high-coupon issues have been protected against redemption for ten years or more after issuance. This still limits their possible price rise, but not inequitably.

In practical terms, we advise the investor in long-term issues to sacrifice a small amount of yield to obtain the assurance of noncallability—say for 20 or 25 years. Similarly, there is an advantage in buying a low-coupon bond* at a discount rather than a high-coupon bond selling at about par and callable in a few years. For the discount—e.g., of a 3½% bond at 63½%, yielding 7.85%—carries full protection against adverse call action.

Straight—i.e., Nonconvertible—Preferred Stocks

Certain general observations should be made here on the subject of preferred stocks. Really good preferred stocks can and do exist, but they are good in spite of their investment form, which is an inherently bad one. The typical preferred shareholder is dependent for his safety on the ability and desire of the company to pay dividends on its common stock. Once the common dividends are omitted, or even in danger, his own position becomes precarious, for the directors are under no obligation to continue paying him unless they also pay on the common. On the other hand, the typical preferred stock carries no share in the company’s profits beyond the fixed dividend rate. Thus the preferred holder lacks both the legal claim of the bondholder (or creditor) and the profit possibilities of a common shareholder (or partner).

These weaknesses in the legal position of preferred stocks tend to come to the fore recurrently in periods of depression. Only a small percentage of all preferred issues are so strongly entrenched as to maintain an unquestioned investment status through all vicissitudes. Experience teaches that the time to buy preferred stocks is when their price is unduly depressed by temporary adversity. (At such times they may be well suited to the aggressive investor but too unconventional for the defensive investor.)

In other words, they should be bought on a bargain basis or not at all. We shall refer later to convertible and similarly privileged issues, which carry some special possibilities of profits. These are not ordinarily selected for a conservative portfolio.

Another peculiarity in the general position of preferred stocks deserves mention. They have a much better tax status for corporation buyers than for individual investors. Corporations pay income tax on only 15% of the income they receive in dividends, but on the full amount of their ordinary interest income. Since the 1972 corporate rate is 48%, this means that $100 received as preferred-stock dividends is taxed only $7.20, whereas $100 received as bond interest is taxed $48. On the other hand, individual investors pay exactly the same tax on preferred-stock investments as on bond interest, except for a recent minor exemption. Thus, in strict logic, all investment-grade preferred stocks should be bought by corporations, just as all tax-exempt bonds should be bought by investors who pay income tax.*

Security Forms

The bond form and the preferred-stock form, as hitherto discussed, are well-understood and relatively simple matters. A bondholder is entitled to receive fixed interest and payment of principal on a definite date. The owner of a preferred stock is entitled to a fixed dividend, and no more, which must be paid before any common dividend. His principal value does not come due on any specified date. (The dividend may be cumulative or noncumulative. He may or may not have a vote.)

The above describes the standard provisions and, no doubt, the majority of bond and preferred issues, but there are innumerable departures from these forms. The best-known types are convertible and similar issues, and income bonds. In the latter type, interest does not have to be paid unless it is earned by the company. (Unpaid interest may accumulate as a charge against future earnings, but the period is often limited to three years.)

Income bonds should be used by corporations much more extensively than they are. Their avoidance apparently arises from a mere accident of economic history—namely, that they were first employed in quantity in connection with railroad reorganizations, and hence they have been associated from the start with financial weakness and poor investment status. But the form itself has several practical advantages, especially in comparison with and in substitution for the numerous (convertible) preferred-stock issues of recent years. Chief of these is the deductibility of the interest paid from the company’s taxable income, which in effect cuts the cost of that form of capital in half. From the investor’s standpoint it is probably best for him in most cases that he should have (1) an unconditional right to receive interest payments when they are earned by the company, and (2) a right to other forms of protection than bankruptcy proceedings if interest is not earned and paid. The terms of income bonds can be tailored to the advantage of both the borrower and the lender in the manner best suited to both. (Conversion privileges can, of course, be included.) The acceptance by everybody of the inherently weak preferred-stock form and the rejection of the stronger income-bond form is a fascinating illustration of the way in which traditional institutions and habits often tend to persist on Wall Street despite new conditions calling for a fresh point of view. With every new wave of optimism or pessimism, we are ready to abandon history and time-tested principles, but we cling tenaciously and unquestioningly to our prejudices.

Commentary on Chapter 4

When you leave it to chance, then all of a sudden you don’t have any more luck.

—Basketball coach Pat Riley

How aggressive should your portfolio be?

That, says Graham, depends less on what kinds of investments you own than on what kind of investor you are. There are two ways to be an intelligent investor:

- by continually researching, selecting, and monitoring a dynamic mix of stocks, bonds, or mutual funds;

- or by creating a permanent portfolio that runs on autopilot and requires no further effort (but generates very little excitement).

Graham calls the first approach “active” or “enterprising”; it takes lots of time and loads of energy. The “passive” or “defensive” strategy takes little time or effort but requires an almost ascetic detachment from the alluring hullabaloo of the market. As the investment thinker Charles Ellis has explained, the enterprising approach is physically and intellectually taxing, while the defensive approach is emotionally demanding.1

If you have time to spare, are highly competitive, think like a sports fan, and relish a complicated intellectual challenge, then the active approach is up your alley. If you always feel rushed, crave simplicity, and don’t relish thinking about money, then the passive approach is for you. (Some people will feel most comfortable combining both methods—creating a portfolio that is mainly active and partly passive, or vice versa.)

Both approaches are equally intelligent, and you can be successful with either—but only if you know yourself well enough to pick the right one, stick with it over the course of your investing lifetime, and keep your costs and emotions under control. Graham’s distinction between active and passive investors is another of his reminders that financial risk lies not only where most of us look for it—in the economy or in our investments—but also within ourselves.

Can You be Brave, or will You Cave?

How, then, should a defensive investor get started? The first and most basic decision is how much to put in stocks and how much to put in bonds and cash. (Note that Graham deliberately places this discussion after his chapter on inflation, forearming you with the knowledge that inflation is one of your worst enemies.)

The most striking thing about Graham’s discussion of how to allocate your assets between stocks and bonds is that he never mentions the word “age.” That sets his advice firmly against the winds of conventional wisdom—which holds that how much investing risk you ought to take depends mainly on how old you are.2 A traditional rule of thumb was to subtract your age from 100 and invest that percentage of your assets in stocks, with the rest in bonds or cash. (A 28-year-old would put 72% of her money in stocks; an 81-year-old would put only 19% there.) Like everything else, these assumptions got overheated in the late 1990s. By 1999, a popular book argued that if you were younger than 30 you should put 95% of your money in stocks—even if you had only a “moderate” tolerance for risk!3

Unless you’ve allowed the proponents of this advice to subtract 100 from your IQ, you should be able to tell that something is wrong here. Why should your age determine how much risk you can take? An 89-year-old with $3 million, an ample pension, and a gaggle of grandchildren would be foolish to move most of her money into bonds. She already has plenty of income, and her grandchildren (who will eventually inherit her stocks) have decades of investing ahead of them. On the other hand, a 25-year-old who is saving for his wedding and a house down payment would be out of his mind to put all his money in stocks. If the stock market takes an Acapulco high dive, he will have no bond income to cover his downside—or his backside.

What’s more, no matter how young you are, you might suddenly need to yank your money out of stocks not 40 years from now, but 40 minutes from now. Without a whiff of warning, you could lose your job, get divorced, become disabled, or suffer who knows what other kind of surprise. The unexpected can strike anyone, at any age. Everyone must keep some assets in the riskless haven of cash.

Finally, many people stop investing precisely because the stock market goes down. Psychologists have shown that most of us do a very poor job of predicting today how we will feel about an emotionally charged event in the future.4 When stocks are going up 15% or 20% a year, as they did in the 1980s and 1990s, it’s easy to imagine that you and your stocks are married for life. But when you watch every dollar you invested getting bashed down to a dime, it’s hard to resist bailing out into the “safety” of bonds and cash. Instead of buying and holding their stocks, many people end up buying high, selling low, and holding nothing but their own head in their hands. Because so few investors have the guts to cling to stocks in a falling market, Graham insists that everyone should keep a minimum of 25% in bonds. That cushion, he argues, will give you the courage to keep the rest of your money in stocks even when stocks stink.

To get a better feel for how much risk you can take, think about the fundamental circumstances of your life, when they will kick in, when they might change, and how they are likely to affect your need for cash:

- Are you single or married? What does your spouse or partner do for a living?

- Do you or will you have children? When will the tuition bills hit home?

- Will you inherit money, or will you end up financially responsible for aging, ailing parents?

- What factors might hurt your career? (If you work for a bank or a homebuilder, a jump in interest rates could put you out of a job. If you work for a chemical manufacturer, soaring oil prices could be bad news.)

- If you are self-employed, how long do businesses similar to yours tend to survive?

- Do you need your investments to supplement your cash income? (In general, bonds will; stocks won’t.)

- Given your salary and your spending needs, how much money can you afford to lose on your investments?

If, after considering these factors, you feel you can take the higher risks inherent in greater ownership of stocks, you belong around Graham’s minimum of 25% in bonds or cash. If not, then steer mostly clear of stocks, edging toward Graham’s maximum of 75% in bonds or cash. (To find out whether you can go up to 100%, see the sidebar on p. 105.)

Once you set these target percentages, change them only as your life circumstances change. Do not buy more stocks because the stock market has gone up; do not sell them because it has gone down. The very heart of Graham’s approach is to replace guesswork with discipline. Fortunately, through your 401(k), it’s easy to put your portfolio on permanent autopilot. Let’s say you are comfortable with a fairly high level of risk—say, 70% of your assets in stocks and 30% in bonds. If the stock market rises 25% (but bonds stay steady), you will now have just under 75% in stocks and only 25% in bonds.5 Visit your 401(k)’s website (or call its toll-free number) and sell enough of your stock funds to “rebalance” back to your 70–30 target. The key is to rebalance on a predictable, patient schedule—not so often that you will drive yourself crazy, and not so seldom that your targets will get out of whack. I suggest that you rebalance every six months, no more and no less, on easy-to-remember dates like New Year’s and the Fourth of July.

WHY NOT 100% STOCKS?

Graham advises you never to have more than 75% of your total assets in stocks. But is putting all your money into the stock market inadvisable for everyone? For a tiny minority of investors, a 100%-stock portfolio may make sense. You are one of them if you:

- have set aside enough cash to support your family for at least one year

- will be investing steadily for at least 20 years to come

- survived the bear market that began in 2000

- did not sell stocks during the bear market that began in 2000

- bought more stocks during the bear market that began in 2000

- have read Chapter 8 in this book and implemented a formal plan to control your own investing behavior.

Unless you can honestly pass all these tests, you have no business putting all your money in stocks. Anyone who panicked in the last bear market is going to panic in the next one—and will regret having no cushion of cash and bonds.

The beauty of this periodic rebalancing is that it forces you to base your investing decisions on a simple, objective standard—Do I now own more of this asset than my plan calls for?—instead of the sheer guesswork of where interest rates are heading or whether you think the Dow is about to drop dead. Some mutual-fund companies, including T. Rowe Price, may soon introduce services that will automatically rebalance your 401(k) portfolio to your preset targets, so you will never need to make an active decision.

The Ins and Outs of Income Investing

In Graham’s day, bond investors faced two basic choices: Taxable or tax-free? Short-term or long-term? Today there is a third: Bonds or bond funds?

Taxable or tax-free? Unless you’re in the lowest tax bracket,6 you should buy only tax-free (municipal) bonds outside your retirement accounts. Otherwise too much of your bond income will end up in the hands of the IRS. The only place to own taxable bonds is inside your 401(k) or another sheltered account, where you will owe no current tax on their income—and where municipal bonds have no place, since their tax advantage goes to waste.7

Short-term or long-term? Bonds and interest rates teeter on opposite ends of a seesaw: If interest rates rise, bond prices fall—although a short-term bond falls far less than a long-term bond. On the other hand, if interest rates fall, bond prices rise—and a long-term bond will outper-forms shorter ones.8 You can split the difference simply by buying intermediate-term bonds maturing in five to 10 years—which do not soar when their side of the seesaw rises, but do not slam into the ground either. For most investors, intermediate bonds are the simplest choice, since they enable you to get out of the game of guessing what interest rates will do.

Bonds or bond funds? Since bonds are generally sold in $10,000 lots and you need a bare minimum of 10 bonds to diversify away the risk that any one of them might go bust, buying individual bonds makes no sense unless you have at least $100,000 to invest. (The only exception is bonds issued by the U.S. Treasury, since they’re protected against default by the full force of the American government.)

Bond funds offer cheap and easy diversification, along with the convenience of monthly income, which you can reinvest right back into the fund at current rates without paying a commission. For most investors, bond funds beat individual bonds hands down (the main exceptions are Treasury securities and some municipal bonds). Major firms like Vanguard, Fidelity, Schwab, and T. Rowe Price offer a broad menu of bond funds at low cost.9

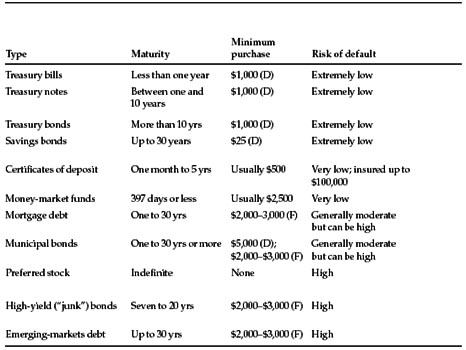

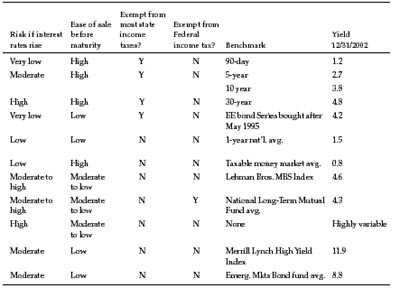

The choices for bond investors have proliferated like rabbits, so let’s update Graham’s list of what’s available. As of 2003, interest rates have fallen so low that investors are starved for yield, but there are ways of amplifying your interest income without taking on excessive risk.10 Figure 4-1 summarizes the pros and cons.

Now let’s look at a few types of bond investments that can fill special needs.

Cash is not Trash

How can you wring more income out of your cash? The intelligent investor should consider moving out of bank certificates of deposit or money-market accounts—which have offered meager returns lately—into some of these cash alternatives:

Treasury securities, as obligations of the U.S. government, carry virtually no credit risk—since, instead of defaulting on his debts, Uncle Sam can just jack up taxes or print more money at will. Treasury bills mature in four, 13, or 26 weeks. Because of their very short maturities, T-bills barely get dented when rising interest rates knock down the prices of other income investments; longer-term Treasury debt, however, suffers severely when interest rates rise. The interest income on Treasury securities is generally free from state (but not Federal) income tax. And, with $3.7 trillion in public hands, the market for Treasury debt is immense, so you can readily find a buyer if you need your money back before maturity. You can buy Treasury bills, short-term notes, and long-term bonds directly from the government, with no brokerage fees, at www.publicdebt.treas.gov. (For more on inflation-protected TIPS, see the commentary on Chapter 2.)

FIGURE 4-1 The Wide World of Bonds

Sources: Bankrate.com, Bloomberg, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Morningstar, www.savingsbonds.gov

Notes: (D): purchased directly. (F): purchased through a mutual fund. “Ease of sale before maturity” indicates how readily you can sell at a fair price before maturity date; mutual funds typically offer better ease of sale than individual bonds. Money-market funds are Federally insured up to $100,000 if purchased at an FDIC-member bank, but otherwise carry only an implicit pledge not to lose value. Federal income tax on savings bonds is deferred until redemption or maturity. Municipal bonds are generally exempt from state income tax only in the state where they were issued.

Savings bonds, unlike Treasuries, are not marketable; you cannot sell them to another investor, and you’ll forfeit three months of interest if you redeem them in less than five years. Thus they are suitable mainly as “set-aside money” to meet a future spending need—a gift for a religious ceremony that’s years away, or a jump start on putting your newborn through Harvard. They come in denominations as low as $25, making them ideal as gifts to grandchildren. For investors who can confidently leave some cash untouched for years to come, inflation-protected “I-bonds” recently offered an attractive yield of around 4%. To learn more, see www.savingsbonds.gov.

Moving Beyond Uncle Sam

Mortgage securities. Pooled together from thousands of mortgages around the United States, these bonds are issued by agencies like the Federal National Mortgage Association (“Fannie Mae”) or the Government National Mortgage Association (“Ginnie Mae”). However, they are not backed by the U.S. Treasury, so they sell at higher yields to reflect their greater risk. Mortgage bonds generally underperform when interest rates fall and bomb when rates rise. (Over the long run, those swings tend to even out and the higher average yields pay off.) Good mortgage-bond funds are available from Vanguard, Fidelity, and Pimco. But if a broker ever tries to sell you an individual mortgage bond or “CMO,” tell him you are late for an appointment with your proctologist.

Annuities. These insurance-like investments enable you to defer current taxes and capture a stream of income after you retire. Fixed annuities offer a set rate of return; variable ones provide a fluctuating return. But what the defensive investor really needs to defend against here are the hard-selling insurance agents, stockbrokers, and financial planners who peddle annuities at rapaciously high costs. In most cases, the high expenses of owning an annuity—including “surrender charges” that gnaw away at your early withdrawals—will overwhelm its advantages. The few good annuities are bought, not sold; if an annuity produces fat commissions for the seller, chances are it will produce meager results for the buyer. Consider only those you can buy directly from providers with rock-bottom costs like Ameritas, TIAA-CREF, and Vanguard.11

Preferred stock. Preferred shares are a worst-of-both-worlds investment. They are less secure than bonds, since they have only a secondary claim on a company’s assets if it goes bankrupt. And they offer less profit potential than common stocks do, since companies typically “call” (or forcibly buy back) their preferred shares when interest rates drop or their credit rating improves. Unlike the interest payments on most of its bonds, an issuing company cannot deduct preferred dividend payments from its corporate tax bill. Ask yourself: If this company is healthy enough to deserve my investment, why is it paying a fat dividend on its preferred stock instead of issuing bonds and getting a tax break? The likely answer is that the company is not healthy, the market for its bonds is glutted, and you should approach its preferred shares as you would approach an unrefrigerated dead fish.

Common stock. A visit to the stock screener at http://screen. yahoo.com/stocks.html in early 2003 showed that 115 of the stocks in the Standard & Poor’s 500 index had dividend yields of 3.0% or greater. No intelligent investor, no matter how starved for yield, would ever buy a stock for its dividend income alone; the company and its businesses must be solid, and its stock price must be reasonable. But, thanks to the bear market that began in 2000, some leading stocks are now outyielding Treasury bonds. So even the most defensive investor should realize that selectively adding stocks to an all-bond or mostly-bond portfolio can increase its income yield—and raise its potential return.12