CHAPTER

FOUR

ELECTRONIC TRADING FOR FIXED INCOME MARKETS

Managing Director

Knight BondPoint

In a short time, technology has revolutionized trading in the fixed income industry, just as it has in other securities markets such as equities, options, and foreign exchange. We’re only at the beginning of sweeping changes expected to touch every participant, from the back office to the trader, from the money manager to the investment advisor, from the regulator to the retail investor.

OVERALL BOND MARKET GROWTH

To appreciate how electronic trading fits into the fixed income markets, it’s important to start with the whole of the U.S. bond market, a market that has doubled in size since 2000. By the close of 2010, there was more than $35 trillion in outstanding debt, according to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA). Treasury and mortgage-related debt accounted for approximately one-fourth of all U.S bond market debt through the close of 2010, followed closely by corporate debt, around 21% of the market. Municipal, agency, money market, and asset-backed debt each represents less than 10% of the aggregate amount outstanding. The entire U.S. equity market capitalization is quite small by comparison, approximately $22 trillion at the end of 2010, according to the World Federation of Exchanges (WFE).

Fixed income trading volumes have also increased. Average daily volume for the U.S. bond categories mentioned was more than $1 trillion in December 2010, with a daily average of approximately $950 billion for the full year, according to SIFMA. That’s up more than 50% from an average of almost $630 billion in 2002, the first year SIFMA included corporate debt in its calculations. Debt once again trumped equities, where average daily exchange-traded U.S. equity volume was $99.3 billion in 2010, calculates SIFMA.

Broken down by SIFMA, trading volumes in U.S. Treasuries accounted for more than half of the 2010 average daily volume, and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) accounted for more than $300 billion. Less-liquid corporate and municipal bonds experienced daily trading volumes of $16.5 billion and $13.3 billion, respectively. A number of factors have contributed to an increase both in the overall size of the bond market, and the volume of daily fixed income trading. Some growth is related to cyclical factors, such as interest rates and the relative weaker performance of equities post-financial crisis in 2008, or driven by one-time events, such as the May 6, 2010 “flash crash” and resulting uncertainty in the equities markets.

But long-term demographic and structural shifts have and will continue to sustain the expansion of fixed income. Quite simply, fixed income is in increasing demand as the U.S. population ages. By 2030, there will be approximately 72.1 million people age 65 and older, more than twice their number in 2000, according to the Administration on Aging, and they will account for 19% of the population by then. Baby Boomers are reallocating from capital appreciation type securities like equities into bonds for income distribution and wealth preservation.

Fixed income market participants in the United States are divided into three groups. Issuers include governments, corporations, banks, and municipalities, and their primary function includes issuing debt to finance various activities and needs of the entity. That debt is underwritten, distributed, and traded in the secondary markets by intermediaries, including investment banks, commercial banks, and interdealer brokers. The investors who buy fixed income include governments, mutual funds, insurance companies, commercial banks, corporations, and retail investors. Of this last group, retail is a growing presence owing in great part to easier access to individual fixed income securities through advances in technology.

THE RISE OF ELECTRONIC TRADING

Since the 1960s, fixed income has been traded predominantly in the secondary over-the-counter (OTC) markets in the United States. Until approximately 2000, most trading took place over telephone, fax, and electronic mail and messaging services across disparate parties, with no exchange or way to link up market participants in a central location. Additionally, the fixed income market consists of numerous individual issues, some three million today, versus approximately 20,000 different equity securities, making the establishment of a central fixed income liquidity hub and/or connectivity that much more difficult.

The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) stepped into the void and in the 1920s and 1930s operated an exchange for corporate, government, and municipal bonds trading. In 2006, NYSE launched the NYSE Bonds platform to replace the NYSE Automated Bond System in hopes of building an electronic trading venue in which buyers and sellers could trade corporate bonds. However, with the lack of a central place for liquidity to congregate and the OTC nature of the fixed income market, electronic trading was much slower to develop than equities.

The typical workflow of a fixed income trade would consist of a number of telephone exchanges between buyers and sellers and intermediaries such as brokers’ brokers or fixed income dealers. Imagine the inefficiencies and errors as the manual nature of finding, pricing, and executing fixed income securities created manual and duplicate workflow activities, with a higher likelihood of data entry errors.

Once technology evolved to make it more cost-effective and efficient to link buyers, and sellers, the fixed income industry was able to move forward. Trade executions moved from the telephone to transactions via fax, then on to e-mails and instant messaging, until the establishment of electronic communications networks (ECNs).

However, fixed income trading has stayed primarily over the counter. The large number of outstanding fixed income issues lack uniformity in the secondary marketplace and are thinly traded when compared with other financial securities traded daily on U.S. exchanges. This fragmented, heterogeneous, less-liquid nature of the fixed income markets has been yet another obstacle in establishing electronic trading.

Despite this backdrop, electronic trading in fixed income securities gained significant traction in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Opportunities arose out of the Internet revolution and emerging Web technologies, and they were supported by the increasing ability for those with foresight to raise capital for businesses pursuing such technologies. At their core, these technologies allowed for a low-cost infrastructure and a faster, more efficient deployment model from which a number of electronic trading venues arose, from bona fide exchanges and multidealer electronic communications networks to single-dealer trading systems. By 2001, some 90 electronic trading systems for fixed income securities were operational, up from only 11 in 1997, according to The Bond Market Association’s annual survey.1

From 2001 to 2005, many of these early entrants into electronic fixed-income trading closed, were consolidated or transformed their business models to new fixed income–related initiatives. Over-investment in the space drove the emergence of too many venues, resulting in excess capacity given the demand for electronic fixed income trading at the time. The survivors were typically well capitalized and often formed as broker-dealer consortiums whose owners were natural users, and/or focused on more standardized and liquid fixed income products such as government and agency bonds and highgrade corporate debt.

It was not until the second half of the decade, post-consolidation, that growth in electronic fixed income trading was fueled finally by growing industry acceptance and the wider adoption of electronic access. Two primary drivers of continued adoption came via the introduction of value-added by various electronic trading venues, as well as more rigorous regulatory oversight of fixed income markets. The ability to perform transactions electronically was an important advance, but the tipping point for adoption was the introduction of more pre- and post-trade services which eliminated redundant workflow processes.

Indeed, pre- and post-trade services further automated aspects of the fixed income trade life cycle beyond the execution itself. This automation of the trade life cycle is often known as Straight Through Processing (STP), which essentially allows for information that has been electronically entered to be transferred from one party to another in the clearance and settlement process without manually reentering the same pieces of information repeatedly over the entire sequence of events. Examples of STP services offered by electronic trading venues include the delivery of confirms and account allocations to portfolio management systems, as well as the delivery of trade execution messages to back office and clearing for post-trade processing. Other types of ancillary services offered by providers of fixed income trading systems include compliance modules to assist in the capture and documentation of regulatory and compliance requirements, as well as risk management and monitoring. These additional services can enhance the operational efficiency of firms engaged in fixed income trading by eliminating and automating duplicative workflow. This automation, in turn, reduces the number of trade errors that must be researched and resolved when compared with the largely manual processes used throughout fixed income trading’s history.

The equities markets adopted the Financial Information eXchange (FIX) as a messaging standard in the early 1990s, to great success. FIX, a technology in the public domain, facilitates real-time electronic exchange of securities transactions. The later adoption of FIX as a protocol for fixed income transactions was one of the primary technological developments in this space over the last decade. Before FIX, efforts to connect and link various fixed income systems without a messaging standard were resource intensive. FIX enabled electronic trading venues to offer post-trade messaging services in support of their STP initiatives. Today FIX handles a variety of messages necessary to conduct fixed income transactions, including transmission of orders and confirmation of trade executions, as well as allows dealers to supply bid or offer information for fixed income securities (Exhibit 4–1). For fixed income dealers and investors, FIX brought efficiency by eliminating duplicative activities and supporting regulatory responsibilities. In essence, FIX enabled electronic trading venues to build a “network effect” of dealers and investors quickly and cost effectively. Once established, these network effects allow electronic venues to create barriers to entry for new competitors.

EXHIBIT 4–1

Diagram of FIX Connectivity between Fixed Income Market Participants

THE IMPACT OF REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS

One regulatory effort in particular had a significant impact in driving increased electronic trading in fixed income. In 2001, the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) approved rules that required broker-dealers who were members of the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD, which is now the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, or FINRA) to report secondary market transactions in certain corporate fixed income securities. These rules were developed to bring greater price transparency to the corporate bond markets by collecting and disseminating fixed income transaction data from and back into the marketplace. Greater transparency, it was perceived by regulators, would reduce bid/ask spreads and subsequently lower investor trading costs associated with purchases and sales of corporate bonds.

This system, managed by FINRA for reporting and disseminating corporate bond trade information, became known as the Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine, or TRACE. TRACE required that eligible transactions in corporate bonds be reported by dealers within 15 minutes of trade completion. TRACE ultimately was expanded in 2010 to cover certain federal government agency debt as well as primary market transactions in eligible corporate bonds.

Additionally, in 2004, the SEC approved proposed rule changes relating to the Municipal Securities Rule Board’s (MSRB) implementation of real-time transaction reporting and price dissemination, detailed in MSRB Release 34-50294. According to the MSRB, the purpose of this rule change—in which eligible transactions were required to be reported to the MSRB’s Real-Time Transaction Reporting System or RTRS facility—was to increase price transparency in municipal securities and enhance surveillance database and audit trails used by enforcement agencies. Similar to TRACE reporting requirements, the MSRB’s rule change shortened reporting requirements from end of day to within 15 minutes of time of trade, in accordance with MSRB Notice 2004-29.

TRACE was successful in lowering trade execution costs for TRACE-eligible securities by 50% and increasing competition in the corporate bond markets, based on a 2005 study by Bessembinder, Maxwel, and Venekatraman.2 In fact, TRACE helped increase market share for smaller dealers while eliminating cost advantages for larger dealers. The industry now had appropriate incentives to enhance operational efficiency via continued adoption and support of fixed income electronic trading: a reduction of bid/ask spreads, lower transaction costs, greater regulatory emphasis on fixed income transactions, and easier access to technology. Electronic trading systems, in turn, were given the opportunity to help users fulfill regulatory obligations by offering services such as TRACE reporting and STP initiatives that could link electronic trading systems to proprietary or third-party systems for message automation.

SHIFT TO A FEE-BASED BROKER-DEALER REVENUE MODEL

The retail brokerage industry shift to fee-based from commission revenue models played a role in driving the adoption of electronic trading in the retail fixed income markets.

Historically, broker-dealers with large retail sales forces held a substantial inventory and conducted predominantly principal trading of fixed income securities with retail accounts via financial advisors. However, over the last decade, many broker-dealers introduced fee-based platforms. Under a fee-based model, accounts were charged a fee based on assets under management at the broker-dealer rather than commissions on individual transactions. For these fee-based accounts, the SEC limited broker-dealers to acting in a principal capacity when effecting trades on their clients’ behalf.

As a result of these limitations in servicing fee-based accounts, broker-dealers sought solutions that enabled fixed income product access and agency execution solutions. Electronic retail platforms such as Knight BondPoint and BondDesk arose to provide these solutions through Web-based financial advisor portals and access to alternative trading system (ATS) multi-dealer platforms. With the loss of principal trading opportunities in a growing number of retail accounts, many broker-dealers looked to broaden their retail distribution beyond their own retail sales force. These retail-centric electronic trading platforms provided that opportunity as well

As of early 2011, there are no formal measurement levels of daily fixed income transactions executed electronically. While TRACE and MSRB reporting requirements dictate that participants report transactions in eligible securities, reporting firms are not required to provide whether the transaction was executed electronically, much less the system or venue upon which the transaction may have taken place. Furthermore, many systems and venues do not publish volume statistics directly to the marketplace, and those that do use a variety of different methodologies for counting and reporting volumes, making comparisons less than scientific.

However, in April 2008, Celent, a division of Oliver Wyman, estimated that 57% of average daily volume of U.S. fixed income products was executed electronically and predicted that adoption would drive the percentage of executions taking place electronically to 62% by 2010. According to Celent, electronic trading has had greater penetration in more-liquid securities, including U.S. Treasuries, with an estimated 80% of daily average trading volume executed electronically at the time of the study. Meanwhile, electronic transactions in agency MBS accounted for 32% of average daily volume.3 Celent went on to estimate that electronic trading was not as well adopted in less-liquid securities such as municipal bonds, corporate bonds and federal agency securities. In fact, only 15% of federal agency security volume, 10% of corporate bond volume, and 8% of municipal bond volume were traded electronically in 2006. Celent predicted that adoption in these securities would be slow, with estimated percentages of daily volumes executed electronically in 2010 of 16% of federal agency securities, 12% of corporate bonds, and 10% of municipal bonds.

UNIVERSE OF ELECTRONIC TRADING PLATFORMS

In this section, we briefly describe the types of trading platforms and types of trading models.

Types of Trading Platforms

While the financial services industry lacks formal definitions to describe various types of electronic fixed income trading platforms, most are grouped by the participants and the type of trading methodology deployed upon these systems.

Interdealer Systems

Allowing fixed income dealers to execute trades electronically and anonymously with each other, interdealer systems utilize an interdealer broker (IDB) as intermediary. Interdealer platforms are most prevalent in Treasury and government agency trading. Typical IDBs provided both electronic and voice capabilities for their clients. Many of these platforms now allow nondealers, such as institutional customers, access to these platforms. Examples of Interdealer Systems include eSpeed, and BrokerTec.

Single-Dealer Client Systems

Owned and operated by major fixed income dealers, these single-dealer client systems typically allow institutional clients to trade a variety of fixed income products electronically directly with the dealer sponsor of the system. Fixed income dealers operating these single-dealer systems act in a principal capacity. Examples include Deutsche Bank’s Autobahn and J.P. Morgan’s JPeX.

Multi-Dealer Client Systems

These systems enable institutional clients to access price quotes from and execute with multiple dealers, and they typically offer pre- and post-trade services as an additional benefit for institutional clients and dealers utilizing the system. Many of the multi-dealer systems in existence today were started as consortiums founded by fixed income dealers. Examples include Tradeweb and MarketAxess.

Exchanges

Offering a system model for fixed income securities in which buyers and sellers match trades, exchanges create liquidity, rather than relying on fixed income market makers to provide price quotes. Transactions are conducted anonymously. An example would be NYSE Bonds.

Odd-Lot Trading Systems

Odd lots are defined by trades under $1 million in par value, and these systems are used by firms buying and selling fixed income securities on behalf of direct retail investors. As a result, most support trading in a variety of bond types. Most odd-lot systems are multi-dealer, but some dealers who specialize in odd lots also have single-dealer systems over which their clients can execute. In addition, odd-lot trading systems are used by institutional customers to facilitate trading in odd-lot positions they may need to buy or sell. Examples include Knight BondPoint, BondDesk, and TMC.

Types of Trading Models

While there are a variety of trading models deployed in order to facilitate electronic trading in fixed income securities, the three most prevalent today are request for quote, order-driven, and auction models. Many electronic platforms now support multiple trading models, depending largely on the need of a user at a given time.

Request for Quote

Typically deployed by multi-dealer client systems and used by institutional customers to execute trades, the request for quote (RFQ) model enables the client to request pricing on a bond or bonds from one or more dealers participating on the multi-dealer platform. Upon receipt of the request, dealers can respond with price quotes. Quotes can then be acted upon and an execution occurs if a bid is hit or an offer is lifted.

Order-Driven

The order-driven model enables participants to place orders against price quotes provided by other participants that are called price makers, liquidity providers, or market makers. Executions occur when orders submitted are matched against price quotes from liquidity providers. Upon a matched order, an execution message is generated for both liquidity provider and liquidity taker. Most of the odd-lot trading systems are order-driven based systems.

Auction Systems

Most often auction systems are used in new issue or book-building activities. Typically these systems allow an issuer or manager of an issue to post details of the offering, such as security, size, and rules of the auction. Subsequently, indications of interest are placed and order are allocated up on close of the auction.

CURRENT TECHNOLOGIES

The evolution of technology in fixed income trading has been consistent with the patterns seen in other asset classes, such as equities, options, and foreign exchange. One of the most significant observations is the diminishing importance of unique graphical user interface (GUI) applications for trading fixed income electronically. A growing percentage of activity taking place on electronic fixed income venues is now originated via an application program interface (API), which has enabled programmatic aggregation of information from multiple and competing electronic platforms.

GUI versus API

The equity markets have certainly led the others in adopting automation. More than 90% of inbound prices and orders in the equity markets arrive at their destination, such as an ECN or exchange, via a FIX API. The percentage of API-delivered prices and orders in the foreign exchange market is not quite that high, but likely represents the vast majority of the volume. In both cases, the ATSs and ECNs in these markets began with GUIs to gain initial adoption and eventually evolved to primarily API-based activity.

Trading in fixed income markets also is following these natural evolutionary steps from single- and multi-dealer systems with proprietary GUIs to the current set of mature fixed income ECNs. The early versions of the electronic trading platforms in this asset class generated most of their price-making and price-taking activity via GUI and usually focused on one or more specific sectors. As a result, many participants on both sides of the market had to manage market activity on multiple GUIs, which introduced inefficiencies and risk, particularly for firms engaged in market making.

In response to requests from the market, ECNs began offering API alternatives. The institution-focused ECNs led the way in this maturation process, and the odd-lot or retail ECNs eventually followed. Initial API integration was seen as costly and time-consuming due to the lack of integration tools as well as to nonstandard proprietary communication protocols used differently at each ECN. However, as ECNs matured, more and more adopted FIX, which allowed easier integration for many firms. Generally, on odd-lot, retail-focused ECNs, the vast majority of quotes are delivered in real-time via API, and less than half of the price taking activity is conducted by API. In the institutional markets the percentages of volume represented by APIs is somewhat higher due to the earlier start and ongoing demand. For example, given the availability of APIs, price makers can now enter prices from one system connected to all the ECNs (or as many as they require).

The Bloomberg Trade Order Management System (TOMS) has been the single-entry system of choice for fixed income dealers participating in the retail market because it combines inventory management with the Bloomberg security master and offers other value-added features. Alternatively, some dealers use proprietary systems to manage their price models and deliver prices to distinct APIs. In most cases, the price models are managed by manual adjustments of spreads to benchmarks, but more automated methods are used for selected instruments, such as the on-the-runs and other highly liquid U.S. Treasuries.

Meanwhile, the buy side has preferred to manage activity from buy-side-oriented order management systems (OMSs), such as Bloomberg’s AIM, Charles River, and Latent Zero. The availability of APIs from all ECNs eliminates the need to monitor and manage extra screens and ensures a smooth integration with post-trade processes. In most cases, the decision point for price taking is still human-based, but it is indicated in the GUI of an OMS as opposed to one from the ECN. The capability exists to accept orders from sophisticated models. Therefore, some larger institutions have employed rules-based or algorithmic trading for a completely automated execution process, but the demand has not yet reached the levels seen in equities and foreign exchange.

In the early history of fixed income ECNs, well-designed GUIs were considered to be a distinctive competitive advantage. In the present era, due to the growing volume of API-based platforms, GUIs are considered by some participants to be a commodity. As of the beginning of 2011, both of the institutional fixed income ECNs in the U.S.—MarketAxess and Tradeweb Markets—offered both GUI and API access for price making and price taking. In addition, the same choice is available at all four of the retail ECNs: BondDesk, Knight BondPoint, TMC, and Tradeweb Retail.

In most cases, the API access uses the FIX protocol, which is consistent with other markets. There remains some distinction based on sector coverage, such as TMC’s focus on municipal bonds, or MarketAxess’s focus on credit, but otherwise the competitive gap related to the participants, inventory, and bond prices has become very small. While the differences among the ECNs have shrunk, the overall demand for access has increased. In fact, the availability of API access was considered a significant contributor to a record year in electronic trading in 2009 and is expected to play an increasing role in the future.

MARKET DATA AND THE AGGREGATION OF FIXED INCOME ECNs

The introduction of market data to the existing API capabilities offered by fixed income ECNs has enabled the next evolutionary phase of electronic trading—aggregation and automation. This follows trading models now commonly used within other asset types, as the availability of market depth across liquidity pools and automated price making are being widely used in equities and foreign exchange. Wider availability of market data from these ECNs also has allowed aggregation tools to become available to the sell and buy side, offering both many advantages.

On the sell side, dealers can use aggregation tools for real-time management of their positions and risks associated with submitting prices that may be inconsistent with the market levels at any moment. A good aggregation application can allow them to compare their current prices with those from many ECN sources to make sure they are not contributing to an inverted market or are otherwise outside of a normal range. More and more dealers who have adopted these technologies are now implementing automated trading models to establish advantages over competitors.

On the buy side, there are decision-making and compliance-based advantages to an aggregated view. A well-developed aggregation platform can show depth of market across all ECNs, providing a level of transparency that has never before been possible. Institutions with a relatively large position of a single bond can now better assess how much appetite exists for that bond, and whether the current best price could be applied to the whole position or, if not, what prices and sizes are available beyond the best price.

On the compliance side, regulatory authorities now require documentation of best execution within an ECN, for example, a printout or electronic record showing that the executed price was within an accepted range of price for that size of trade at the moment of the trade. However, some internal compliance departments require a stricter standard and expect their traders and portfolio managers to document best execution across the entire market (i.e., all ECNs). A commercially available aggregation product can provide this capability without any development, allowing a firm to quickly ramp up to this higher standard. Some experts believe that regulatory authorities are considering requiring this level of compliance market wide in the future.

RETAIL-FIXED INCOME MARKET PARTICIPATION

Retail fixed income investors can gain access to fixed income markets utilizing a variety of available investment vehicles, including mutual funds, closed-end funds, unit investment trusts (where a professional money manager is utilized to select and manage a portfolio of fixed income securities), and fixed income–oriented exchange-traded funds, or ETFs. Retail investors can also manage a portfolio of fixed income securities through direct ownership in a brokerage account. As of 2009, retail investors held some $2.2 trillion in fixed income mutual funds, according to the Investment Company Institute’s Investment Company Fact Book. Another $107 billion in bonds were owned through ETFs in 2009. While comprehensive data on individual bond ownership by retail investors are somewhat limited, we do know that retail investors are significant participants in the municipal and Treasury markets. According to SIFMA, individuals owned $1.06 trillion in municipal bonds through the third quarter of 2010, more than one-third of total ownership including funds, banks, and insurers. Retail accounts for a smaller percentage of Treasuries owned compared with institutions, but nonetheless held $1.08 trillion in Treasuries through the third quarter of 2010.

Regulatory efforts targeting transparency have helped provide the industry with good insight into retail participation in corporate, agency, and municipal securities through the collection and dissemination of trade data. Data published by FINRA indicate that retail transaction volumes have grown substantially since 2007. In addition, retail has accounted for a larger percentage of overall transactions. For example, TRACE data indicate the following:

• Average daily secondary investment grade market trades = 28,349; 79% of those transactions were for under $100,000 in par value (typical of retail) in Q3 2010, up from 71% in 2007.

• Average daily high-yield transaction = 8,307; 63% under $100,000 in par value in Q3 2010, up from 53% in 2007.

In a pattern similar to investment-grade corporate transactions, data provided by the MSRB also highlight that retail investors are increasingly active participants.

• In Q4 2010, 75% of municipal transactions were for under $100,000 in par value.

RETAIL ACCESS TO INDIVIDUAL BONDS

Retail investors have traditionally bought and sold individual fixed income securities through a financial intermediary affiliated with a broker-dealer. A decade ago, the process would entail a number of emails, phone calls, and/or faxes between the retail investor and financial advisor, and then the financial advisor and fixed income trader or sales liaison. Additional emails, phone calls, and faxes could take place with the fixed income trader or sales liaison and other traders within the firm, and between traders and sales people at other firms. Then, upon the retail account selecting a bond or bonds to purchase, it was likely that the bond or some of the bonds may no longer be available, or available only in a different quantity or price than originally indicated. Hence, more phone calls, faxes, and emails would take place among the retail account, financial advisor, and trade desk in order to complete the transaction.

This inefficient process was first addressed with the growth of Web technologies in the mid-to-late 1990s, via simple Web applications that enabled fixed income professionals to search a list of offerings consolidated in a single database. At that time, fixed income dealers would fax or email a list of inventory to the operators of these systems, and data entry personnel would manually enter the bond inventories received into the centralized database. These systems were often described as an “Electronic Blue List,” in reference to the daily digest and advertisement of fixed income offerings for municipal and corporate securities created and distributed by Standard & Poor’s on blue newspaper. Users of these Web systems could search a database of offerings by various bond-related criteria, including maturities, ratings, and yields. Dealer contact information was identified on each offering and users of the system would place phone calls to negotiate trades.

These Web-based systems were augmented in the early 2000s with advanced functionality to include the ability to route orders electronically to dealers offering bonds through the system, as well as additional capabilities for dealers to send inventory to the system via API. In addition, versions of these systems were developed for use by financial advisors and for direct use by retail accounts with the inclusion of order entry and order routing capabilities to an internal trading desk.

These enhanced capabilities offered by various providers of electronic trading systems coincided with many online brokerages’ strategic plans to expand their product offerings beyond equities, options, and mutual funds to include access to individual bonds. Hence, through collaboration between online brokerages and providers of electronic trading systems, the retail investor was able to search and transact individual fixed income securities electronically via Web-based applications that were tightly integrated into online brokerage technology. Today, these fixed income portals allow retail investors to search a large number of both primary and secondary offerings, conduct price discovery, build portfolios and bond ladders consisting of individual securities, and execute transactions electronically.

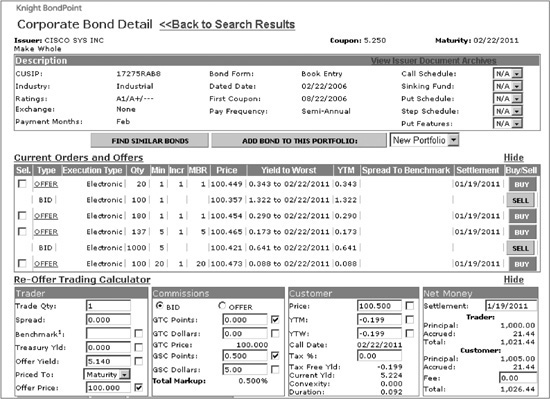

Exhibits 4–2 through 4–5 are examples of Web-based applications and searches for municipal bonds (Exhibits 4–2 and 4–3) and corporate bonds (Exhibits 4–4 and 4–5) as provided by Knight BondPoint.

EXHIBIT 4–2

Multi-Variable Municipal Bond Screener

EXHIBIT 4–3

Municipal Bond Screener Results

EXHIBIT 4–4

Corporate Bond Screener Results

EXHIBIT 4–5

Live Executable Quotes from Multiple Dealers

FIXED INCOME PRICING

When transacting in secondary fixed income markets, broker-dealers typically act in one of three possible capacities when dealing with retail investors.

Broker-dealers acting in a principal capacity buy or sell bonds to retail investors for their own account, profiting from this activity by collecting the bid/ask spread on the transaction(s). For example, an investor may wish to sell a bond from his portfolio, the broker-dealer serving as intermediary on the transaction may take the bond into its own inventory in hopes of selling to another investor or broker-dealer at a higher price in the future.

Broker-dealers acting in a riskless-principal transaction facilitate retail transactions by finding a buyer or seller of a fixed income instrument prior to execution, profiting from the transaction by applying a markup or markdown to the price of the bond for the retail investor. For example, an investor may wish to sell a bond from his portfolio and so sends the request to the broker-dealer for pricing. Upon the receipt, the broker-dealer may send the request to other broker-dealers and, upon receiving prices for the instrument from interested parties, may provide a slightly lower price than received from other broker-dealers as a price at which the retail investor can sell the instrument. Factors affecting the amount of markup or markdown on secondary transactions include the size of the transaction and/or the maturity of the instrument.

When acting in agency capacity, broker-dealers charge retail investors commissions on secondary market transactions. As in a riskless-principal transaction, the broker-dealer serving as intermediary offers the retail investor the best price available for the instrument. However, rather than marking up or down, the broker-dealer adds a commission to the transaction. These commissions are typically set in schedules that are made available to retail investors and, while they reflect the different business models of competing broker-dealers, follow a general pattern. Retail customers typically pay a price per trade or execution, additional costs per security either included or per unit, with minimum and maximum charges. These costs to the retail investor have dropped over time as it has become more efficient for broker-dealers to offer fixed income trading products and services to their customers. Some broker-dealers do not charge any commissions for certain transactions such as secondary treasuries and offer commissions on other products that are not too different than equity commissions.

KEY POINTS

• Long-term demographic and structural shifts have and will continue to sustain the expansion of the fixed income market and trading volumes.

• Retail investors are a growing presence due in great part to easier access to individual fixed income securities through advances in technology.

• The structure of the fixed income market slowed the adoption of electronic trading compared with other asset classes such as equities and foreign exchange.

• The introduction of Web-based technologies and access to capital helped fuel the expansion of numerous electronic trading venues in the 1990s and early 2000s, followed by a period of consolidation.

• Key technology advancements included automation through Straight Through Processing, electronic connectivity through FIX, access through APIs, and the integration of market data onto trading platforms.

• Regulatory requirements including real-time transaction reporting, price dissemination, and best execution documentation further spurred the move toward electronic trading.

• As the retail brokerage industry shifted to a fee-based model and looked to broaden their distribution, demand for electronic retail platforms increased.

• Greater efficiencies in fixed income market access and trading have pushed commissions down, helping to attract an even greater retail investor presence.