CHAPTER

NINE

U.S. TREASURY SECURITIES

Vice President

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

FRANK J. FABOZZI, PH.D., CFA, CPA

Professor of Finance

EDHEC Business School

U.S. Treasury securities are direct obligations of the U.S. government issued by the Department of the Treasury. They are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government and are therefore considered to be free of credit risk. Issuance to pay off maturing debt and raise needed funds has created a stock of marketable Treasury securities that totaled $8.9 trillion on December 31, 2010.1 The creditworthiness and supply of the securities has resulted in a highly liquid round-the-clock secondary market with high levels of trading activity and narrow bid/ask spreads.

Because of their liquidity, Treasury securities are commonly used to price and hedge positions in other fixed income securities and to speculate on the course of interest rates. The securities’ creditworthiness and liquidity also makes them a widespread benchmark for risk-free rates. These same attributes make Treasury securities a key reserve asset of central banks and other financial institutions. Moreover, exemption of interest income from state and local taxes helps make the securities a popular investment asset to institutions and individuals.

As of June 30, 2010, foreign and international investors held 46% of the publicly held Treasury debt.2 Federal Reserve Banks held an additional 9% of the debt. The remaining public debt was held by pension funds (8%), mutual funds (7%), state and local treasuries (6%), depository institutions (3%), insurance companies (3%), and other miscellaneous investors, including individuals (17%).

In this chapter, we discuss U.S. Treasury securities. Our focus is on marketable Treasury securities.

TYPES OF SECURITIES

Treasury securities are issued as either discount or coupon securities. Discount securities pay a fixed amount at maturity, called face value or par value, with no intervening interest payments. Discount securities are so called because they are issued at a price below face value with the return to the investor being the difference between the face value and the issue price. Coupon securities are issued with a stated rate of interest, pay interest every six months, and are redeemed at par value (or principal value) at maturity. Coupon securities are issued at a price close to par value with the return to the investor being primarily the coupon payments received over the security’s life.

The Treasury issues securities with original maturities of one year or less as discount securities. These securities are called Treasury bills. The Treasury currently issues bills with original maturities of 4 weeks (1 month), 13 weeks (3 months), 26 weeks (6 months), and 52 weeks (1 year) as well as cash-management bills with various maturities. On December 31, 2010, Treasury bills accounted for $1.8 trillion (20%) of the $8.9 trillion in outstanding marketable Treasury securities.

Securities with original maturities of more than one year are issued as coupon securities. Coupon securities with original maturities of more than 1 year but not more than 10 years are called Treasury notes. The Treasury currently issues notes with maturities of 2 years, 3 years, 5 years, 7 years, and 10 years. On December 31, 2010, Treasury notes accounted for $5.6 trillion (63%) of the outstanding marketable Treasury securities.

Coupon securities with original maturities of more than 10 years are called Treasury bonds. The Treasury currently issues bonds with a maturity of 30 years. On December 31, 2010, Treasury bonds accounted for $893 billion (10%) of the outstanding marketable Treasury securities. In the past, the Treasury issued callable bonds. The last callable bond was issued in 1984 and the last callable bond outstanding was called in 2009.

In January 1997, the Treasury began selling Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). The principal of these securities is adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index for urban consumers. Semiannual interest payments are a fixed percentage of the inflation-adjusted principal and the inflation-adjusted principal is paid at maturity. On December 31, 2010, TIPS accounted for $616 billion (7%) of the outstanding marketable Treasury securities. As these securities are discussed in Chapter 18, the remainder of this section focuses on nominal (or fixed-principal) Treasury securities.

THE PRIMARY MARKET

Marketable Treasury securities are sold in the primary market through sealed-bid, single-price (or uniform price) auctions. Each auction is announced one or more days in advance by means of a Treasury Department press release. The announcement provides details of the offering, including the offering amount and the term and type of security being offered, and describes some of the auction rules and procedures.

Treasury auctions are open to all entities. Bids must be made in multiples of $100 (with a $100 minimum) and submitted to the Treasury or through an authorized financial institution. Competitive bids must be made in terms of yield and must typically be submitted by 1:00 p.m. eastern time on auction day. Noncompetitive bids must typically be submitted by noon on auction day.3

All noncompetitive bids from the public up to $5 million are accepted. The lowest yield (i.e., highest price) competitive bids are then accepted up to the yield required to cover the amount offered (less the amount of noncompetitive bids). The highest yield accepted is often called the stop-out yield. All accepted tenders (competitive and noncompetitive) are awarded at the stop-out yield. There is no maximum acceptable yield, and the Treasury does not add to or reduce the size of the offering according to the strength of the bids.

Historically, the Treasury auctioned securities through multiple-price (or discriminatory) auctions. With multiple-price auctions, the Treasury still accepted the lowest-yielding bids up to the yield required to sell the amount offered (less the amount of noncompetitive bids), but accepted bids were awarded at the particular yields bid, rather than at the stop-out yield. Noncompetitive bids were awarded at the weighted-average yield of the accepted competitive bids rather than at the stop-out yield. In September 1992 the Treasury started conducting single-price auctions for the 2- and 5-year notes. In November 1998 the Treasury adopted the single-price method for all auctions.

Within minutes of the 1:00 p.m. auction deadline, the Treasury announces the auction results. Announced results include the stop-out yield, the associated price, and the proportion of securities awarded to those investors who bid exactly the stop-out yield. For notes and bonds, the announcement includes the coupon rate of the new security. The coupon rate is set to be that rate (in increments of 1/8 of 1%) that produces the price closest to, but not above, par when evaluated at the yield awarded to successful bidders.

Accepted bidders make payment on issue date through a Federal Reserve account or account at their financial institution, or they provide payment in full with their tender. Marketable Treasury securities are issued in book-entry form and held in the commercial book-entry system operated by the Federal Reserve Banks or in other accounts maintained by the Treasury.

Primary Dealers

While the primary market is open to all investors, the primary government securities dealers play a special role. Primary dealers are firms with which the Federal Reserve Bank of New York interacts directly in the course of its open market operations. Among their responsibilities, primary dealers are expected to participate consistently as counterparty to the New York Fed in its execution of open market operations, provide the New York Fed’s trading desk with market commentary and market information, participate in all auctions of U.S. government debt, and make reasonable markets for the New York Fed when it transacts on behalf of its foreign official account holders. The dealers must also meet certain minimum capital requirements. The 18 primary dealers as of December 31, 2010 are listed in Exhibit 9–1.

EXHIBIT 9–1

Primary Government Securities Dealers as of December 31, 2010

Historically, Treasury auction rules tended to facilitate bidding by the primary dealers. In August 1991, however, Salomon Brothers Inc. admitted deliberate and repeated violations of auction rules. While the rules preclude any bidder from being awarded more than 35% of any issue, Salomon amassed significantly larger positions by making unauthorized bids on behalf of their customers. For the five-year note auctioned on February 21, 1991, for example, Salomon bid for 105% of the issue (including two unauthorized customer bids) and was awarded 57% of the issue. Rule changes enacted later that year allowed any government securities broker or dealer to submit bids on behalf of customers and facilitated competitive bidding by nonprimary dealers.4

Auction Schedule

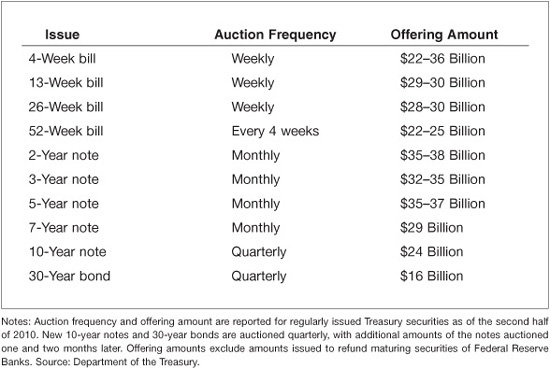

To minimize uncertainty surrounding auctions, and thereby reduce borrowing costs, the Treasury offers securities on a regular, predictable schedule as shown in Exhibit 9–2. Four-, 13-, and 26-week bills are offered weekly, and 52-week bills are offered every four weeks. Four-week bills are typically announced for auction on Monday, auctioned the following Tuesday, and issued the following Thursday. Thirteen- and 26-week bills are typically announced for auction on Thursday, auctioned the following Monday, and issued on the following Thursday (one week after they are announced for auction). Fifty-two week bills are typically announced for auction on Thursday, auctioned the following Tuesday, and issued on the following Thursday. Cash-management bills are issued when required by the Treasury’s short-term cash-flow needs, and not on a regular schedule.

EXHIBIT 9–2

Auction Schedule for U.S. Treasury Securities

Two-, 3-, 5-, and 7-year notes are offered monthly. Two-, 5-, and 7-year notes are usually announced for auction in the second half of the month, auctioned a few days later, and issued on the last day of the month. Three-year notes are usually announced for auction in the first half of the month, auctioned a few days later, and issued on the 15th of the month.

Ten-year notes and 30-year bonds are issued as a part of the Treasury’s quarterly refunding in February, May, August, and November. The Treasury holds a press conference on the first Wednesday of the refunding month (or on the last Wednesday of the preceding month) at which it announces details of the upcoming auctions. The auctions then take place the following week, with issuance on the 15th of the refunding month.

While the Treasury seeks to maintain a regular issuance cycle, its borrowing needs change over time. Most recently, the financial crisis and the government’s response increased the Treasury’s borrowing needs, resulting in increased issuance and a rising stock of outstanding Treasury securities. As a consequence, the Treasury increased the issuance frequency of some securities, such as the three-year note (from quarterly to monthly), and reintroduced issuance of other securities, including the 52-week bill (in 2008) and the seven-year note (in 2009).

In addition to maintaining a regular issuance cycle, the Treasury tries to maintain a stable issue size for issues of a given maturity. Public offering amounts as of the second half of 2010 were $22 to $36 billion for bills, $24 to $38 billion for notes, and $16 billion for the 30-year bond. Issue sizes have also changed in recent years in response to the government’s increased funding needs. Issue sizes for two-year notes, for example, rose from $18 billion in mid 2007 to $44 billion in late 2009.

Reopenings

While the Treasury regularly offers new securities at auction, it often offers additional amounts of outstanding securities. Such additional offerings are called reopenings. Current Treasury practice is to reopen 10-year notes and 30-year bonds one and two months after their initial issuance. Moreover, shorter-term bills are typically fungible with previously issued and outstanding bills, so that every 13-week bill is a reopening of a previously issued 26-week bill, and every 4-week bill is a reopening of a previously issued 13- and 26-week bill. The Treasury also reopens securities on an ad hoc basis from time to time.

Buybacks

To maintain the sizes of its new issues and help manage the maturity of its debt in a time of federal budget surpluses, the Treasury launched a debt buyback program in January 2000. Under the program, the Treasury redeemed outstanding unmatured Treasury securities by purchasing them in the secondary market through reverse auctions. Buyback operations were announced one day in advance. Each announcement contained details of the operation, including the operation size, the eligible securities, and some of the operation rules and procedures.

The Treasury conducted 45 buyback operations between March 2000 and April 2002 (as of December 2010, there were no operations since April 2002). Operation sizes ranged from $750 million par to $3 billion par, with all but three between $1 and $2 billion. The number of eligible securities in the operations ranged from 6 to 26, but was more typically in the 10 to 13 range. Eligible securities were limited to those with original maturities of 30 years, consistent with the Treasury’s goal of using buybacks to prevent an increase in the average maturity of the public debt.

THE SECONDARY MARKET

Secondary trading in Treasury securities occurs in a multiple-dealer over-the-counter market rather than through an organized exchange. Trading takes place around the clock during the week, from the three main trading centers of Tokyo, London, and New York. As shown in Exhibit 9–3, the vast majority of trading takes place during New York trading hours, roughly 7:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. eastern time. The primary dealers are the principal market makers, buying and selling securities from customers for their own accounts at their quoted bid and ask prices. In 2010, primary dealers reported daily trading activity in the secondary market that averaged $565 billion per day.5

EXHIBIT 9–3

Trading Volume of U.S. Treasury Securities by Half Hour

Interdealer Brokers

In addition to trading with their customers, the dealers trade among themselves through interdealer brokers. The brokers offer the dealers and certain other financial firms proprietary electronic screens or electronic trading platforms that post the best bid and offer prices of the participating firms, along with the associated quantities bid or offered (minimums are $5 million for bills and $1 million for notes and bonds). The firms execute trades by notifying the brokers (by phone or electronically), who then post the resulting trade price and size. Interdealer brokers thus facilitate information flows in the market while providing anonymity to the trading firms. In compensation for their services, the brokers charge a small fee.

The interdealer market has undergone significant structural change in recent years. Until 1999, nearly all trading in the IDB market for U.S. Treasury securities occurred over the phone via voice-assisted brokers. Voice-assisted brokers provide firms with proprietary electronic screens that post the best bid and offer prices, along with the associated quantities, but trades are executed over the phone. Brokers then post the resulting trade price and size on their screens.

In 1999, Cantor Fitzgerald introduced its fully automated eSpeed electronic trading platform, whereby trades are executed electronically so that buyers are matched to sellers without human intervention. In 2000, BrokerTec, a rival electronic trading platform, began operations. Over the span of a few years, nearly all trading of the most actively traded Treasury securities migrated to these electronic platforms.6 eSpeed was subsequently spun off from Cantor in a public offering and later merged with BGC Partners, and BrokerTec was acquired by ICAP.

Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve is another important participant in the secondary market for Treasury securities by virtue of its open market operations, security holdings, and surveillance activities. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York buys and sells Treasury securities through open market operations as one of the tools used to implement the monetary policy directives of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). As of June 30, 2010, the Federal Reserve Banks held $777 billion in Treasury securities, or 9% of the publicly held stock. The New York Fed also follows and analyzes the Treasury market and communicates market developments to other government agencies, including the Federal Reserve Board and the Treasury Department.

The financial crisis had a significant effect on the Fed’s participation in the Treasury market and hence on its holdings. Early in the crisis, the Fed reduced its holdings of Treasury securities to finance the introduction of new liquidity facilities. It thereby sold many securities, or did not reinvest the proceeds of maturing securities. As a result, the Fed’s holdings of Treasury securities declined from about $790 billion in mid 2007 to about $480 billion in mid 2008.

In March 2009, the Fed announced a program to purchase up to $300 billion of longer-term Treasury securities, following an earlier announcement to purchase agency MBS and agency debt securities. The full $300 billion was ultimately purchased by the end of October 2009. In August 2010, the Fed then announced it would reinvest principal payments from its agency MBS and agency debt securities in longer-term Treasury securities, and in November 2010 it announced its intent to purchase an additional $600 billion in longer-term Treasury securities by the end of June 2011. By December 29, 2010, the Fed’s holdings of Treasury securities had grown to $1.0 trillion.

Trading Activity

While the Treasury market is extremely active and liquid, much of the activity is concentrated in a small number of the roughly 300 issues outstanding. The most recently issued securities of a given maturity, called on-the-run securities, are particularly active. Analysis of data from GovPX, Inc., a firm that tracks interdealer trading activity, shows that on-the-run issues account for 70% of trading volume. Older issues of a given maturity are called off-the-run securities. While nearly all Treasury securities are off-the-run, they account for only 24% of interdealer trading.

The remaining 6% of interdealer trading occurs in when-issued securities. When-issued securities are securities that have been announced for auction but not yet issued. When-issued trading facilitates price discovery for new issues and can serve to reduce uncertainty about bidding levels surrounding auctions. The when-issued market also enables dealers to sell securities to their customers in advance of the auctions, and thereby bid competitively with relatively little risk. While most Treasury market trades settle the following day, trades in the when-issued market settle on the issue date of the new security.

There are also notable differences in trading activity by issue type, with trading concentrating in the intermediate-term notes. According to data reported to the Fed by the primary dealers, Treasury bills only accounted for 15% of trading activity in 2010, even though they accounted for 20% of marketable Treasury securities outstanding at the end of the year. At the long end, bonds accounted for only 6% of activity, even though they accounted for 10% of marketable securities outstanding. Data for the on-the-run Treasury notes from BrokerTec suggests that the 2-, 5-, and 10-year notes in particular are most active, with average daily trading volume in 2009 of $25, $24, and $23 billion, respectively. In contrast, average daily volume in the 3- and 7-year notes was $10 and $5 billion, respectively.7

Quoting Conventions for Treasury Bills

The convention in the Treasury market is to quote bills on a discount rate basis. The rate on a discount basis is computed as:

![]()

where

Yd = the rate on a discount basis,

F = the face value,

P = the price,

t = the number of days to maturity.

For example, the 26-week bill auctioned August 18, 2008 sold at a price (P) of $98.999 per $100 face value (F). At issue, the bill had 182 days to maturity (t). The rate on a discount basis is then calculated as:

![]()

Conversely, given the rate on a discount basis, the price can be computed as:

![]()

For our example,

![]()

The discount rate differs from more standard return measures for two reasons. First, the measure compares the dollar return with the face value rather than the price. Second, the return is annualized based on a 360-day year rather than a 365-day year. Nevertheless, the discount rate can be converted to a bond-equivalent yield (as discussed in Chapter 6), and such yields are often reported alongside the discount rate.

Treasury bill discount rates are typically quoted to two decimal places in the secondary market, so that a quoted discount rate might be 1.18%. For more active issues, the last digit is often split into halves, so that a quoted rate might be 1.175%.

Typical bid/ask spreads in the interdealer market for the on-the-run bills are 0.5 basis points. A basis point equals one one-hundredth of a percentage point, so that quotes for a half basis point spread might be 1.175%/1.17%. Spreads vary with market conditions, ranging from 0 to about 2 basis points most of the time. A zero spread is called a “locked market” and can persist in the interdealer market because of the transaction fee paid to the broker who mediates a trade. Bid/ask spreads are typically wider outside of the interdealer market and for less active issues.

Quoting Conventions for Treasury Coupon Securities

In contrast to Treasury bills, Treasury notes and bonds are quoted in the secondary market on a price basis in points in which one point equals 1% of par.8 The points are split into units of 32nds, so that a price of 97–14, for example, refers to a price of 97 and 14/32 or 97.4375. The 32nds are themselves split by the addition of a plus sign or a number, with a plus sign indicating that half a 32nd (or 1/64) is added to the price and a number indicating how many eighths of 32nds (or 256ths) are added to the price. A price of 97–14+ therefore refers to a price of 97 and 14.5/32 or 97.453125, whereas a price of 97–142 refers to a price of 97 and 14.25/32 or 97.4453125. The yield to maturity, discussed in Chapter 6, is typically reported alongside the price.

Typical bid/ask spreads in the interdealer market for the on-the-run notes range from 1/128 point for the 2-year note to 1/32 point for the 10-year note, as shown in Exhibit 9–4. A 2-year note might thus be quoted as 99–082/99–08+, whereas a 10-year note might be quoted as 95–23/95–24. As with bills, the spreads vary with market conditions, and are usually wider outside of the interdealer market and for less active issues.

EXHIBIT 9–4

Bid/Ask Spreads for U.S. Treasury Securities

ZERO-COUPON TREASURY SECURITIES

Zero-coupon Treasury securities are created from existing Treasury notes and bonds through coupon stripping. (The Treasury does not issue them.) Coupon stripping is the process of separating the coupon payments of a security from the principal and from one another. After stripping, each piece of the original security can trade by itself, entitling its holder to a particular payment on a particular date. A newly issued 10-year Treasury note, for example, can be split into its 20 semiannual coupon payments (called coupon strips) and its principal payment (called the principal strip), resulting in 21 individual securities. As the components of stripped Treasury securities consist of single payments (with no intermediate coupon payments), they are often referred to as zero coupons or zeros, as well as strips.

As they make no intermediate payments, zeros sell at discounts to their face value, and frequently at deep discounts due to their oftentimes long maturities. On February 11, 2011, for example, the closing bid price for the November 2040 principal strip was just $22.83 (per $100 face value). As zeros have known cash values at specific future dates, they enable investors to closely match their liabilities with Treasury cash flows, and are thus popular with pension funds and insurance companies. Zeros also appeal to speculators because their prices are more sensitive to changes in interest rates than coupon securities with the same maturity date.

The Treasury introduced its Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal Securities (STRIPS) program in February 1985 to improve the liquidity of the zero-coupon market. The program allows the individual components of eligible Treasury securities to be held separately in the Federal Reserve’s book-entry system. Institutions with book-entry accounts can request that a security be stripped into its separate components by sending instructions to a Federal Reserve Bank. Each stripped component receives its own CUSIP (or identification) number and can then be traded and registered separately. The components of stripped Treasury securities remain direct obligations of the U.S. government. The STRIPS program was originally limited to new coupon security issues with maturities of 10 years or longer, but was expanded to include all new coupon issues in September 1997.

Since May 1987, the Treasury has also allowed the components of a stripped Treasury security to be reassembled into their fully constituted form. An institution with a book-entry account assembles the principal component and all remaining interest components of a given security and then sends instructions to a Federal Reserve Bank requesting the reconstitution.

As of December 31, 2010, $197 billion of fixed-principal Treasury notes and bonds were held in stripped form, representing 3% of the $6.5 trillion in fixed-principal coupon securities outstanding.9 There is wide variation across issue types and across issues of a particular type in the rate of stripping. As of December 31, 2010, 20% of bonds were stripped but only 0.3% of notes were stripped. Among the notes, one issue was 8% stripped, while 89 issues were not stripped at all. On a flow basis, securities were stripped at a rate of $36.0 billion per month in the last quarter of 2010, and reconstituted at a rate of $34.1 billion per month.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Neel Krishnan for his research assistance. Michael Fleming’s views expressed in this chapter are his and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System.

KEY POINTS

• U.S. Treasury securities are obligations of the U.S. government issued by the Department of the Treasury.

• Marketable Treasury securities are sold in the primary market through sealed-bid, single-price (or uniform price) auctions.

• Treasury securities are issued as either discount securities (bills) or coupon securities (notes and bonds) and are issued as either fixed-principal or inflation-protected securities.

• Secondary trading in Treasury securities occurs in a multiple-dealer over-the-counter market rather than through an organized exchange.

• Treasury securities trade in a highly liquid secondary market, and are used by market participants as a pricing and hedging instrument, risk-free benchmark, reserve asset, and investment asset.

• Zero-coupon Treasury securities are created from existing Treasury notes and bonds through the Treasury’s Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal Securities (STRIPS) program. Coupon stripping is the process of separating the coupon payments of a security from the principal and from one another.