CHAPTER

FIFTEEN

STRUCTURED NOTES AND CREDIT-LINKED NOTES

JOHN D. FINNERTY, PH.D.

Professor of Finance

Fordham University

Managing Principal

Finnerty Economic Consulting, LLC

RACHAEL W. PARK

Senior Associate

Finnerty Economic Consulting, LLC

Structured notes and credit-linked notes are debt instruments that provide customized interest or principal payments that depend on the performance of a specified reference asset, market price, index, interest rate, or some other market quantity. They enable investors to express a view on the future performance of the reference item as part of their investment management program or protect their other assets against adverse changes in the value of the underlying item as part of their risk management program. A structured note combines a conventional fixed-rate or floating-rate note with an embedded derivative instrument, such as an option or a swap, which links the payments on the note to the reference item. A credit-linked note (CLN) is a particular form of structured note in which the derivative instrument is a credit default swap or some other form of credit derivative.

Structured notes and CLNs provide investors with investment opportunities that they might find difficult or expensive to access in other ways, for example, because of transaction costs, regulatory restrictions, or other market frictions. Generally, any derivative instrument can be structured either as a stand-alone financial instrument, such as a swap or a forward, or it can be attached to a conventional note to form a structured note. Structured notes have been issued regularly at least since the mid 1980s. They emerged as an important instrument in the early 1990s when financial engineers regularly began crafting new forms of structured notes, including in particular CLNs, by attaching derivative instruments to medium-term notes in the United States, Europe, and Asia. According to Bloomberg L.P., the volume of structured notes issued in the U.S. market increased nearly 30-fold from $8 billion in 2000 to $230 billion in 2010.

CLNs have been very popular since the mid 1990s, soon after the credit derivatives market first began to develop. The volume of CLNs issued in the U.S. market increased more than tenfold from $0.6 billion in 2000 to $6.5 billion in 2007, according to Bloomberg L.P. However, the global financial crisis that started in late 2007 caused a significant reduction in the volume of CLN issuance to $0.4 billion in 2010. Nevertheless, the new issue volumes for CLNs and other structured notes are likely to increase as the world economy grows following the financial crisis and investors and hedgers once again seek the risk/return opportunities that these instruments can provide.

STRUCTURED NOTES

A structured note is a hybrid security that contains an embedded derivative instrument, which transforms the interest payments or the principal payments (or both) by making at least some of these payments contingent on a specified reference asset, market price, index, interest rate, or some other market quantity. The term structured refers to incorporating a derivative into the structure of the note to give the reconfigured note the desired financial properties. Adding the contingency feature alters the risk/return profile of the (structured) note to suit the investment preferences of investors.

Instead of making the traditional interest payments that are either fixed in amount or tied to a specified floating-rate index, a structured note pays interest in amounts that are determined by some formula tied to the movement of a stock price or index, a bond or loan price, a commodity price, a foreign exchange rate, or some other financial variable. Some structured notes are designed to have relatively conservative risk/return profiles so as to be useful in reducing portfolio risk, whereas others are designed to have more aggressive risk/return profiles, for example, by leveraging returns so as to provide the possibility for substantial gain or loss. The nature and design of the embedded derivative instrument determines the structured note’s risk/return profile.

Characteristics of Structured Notes

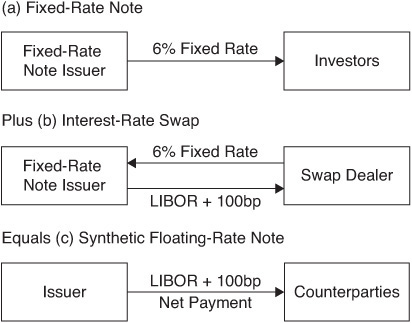

Although a floating-rate note is not considered a structured note, the relationship between a fixed-rate note and a floating-rate note can be used to illustrate the distinguishing characteristic of a structured note, which is the packaging of a derivative with a conventional note. Start with a 10-year note that pays a 6% fixed rate annually. Add a 10-year fixed-for-floating interest-rate swap in which the note issuer pays LIBOR + 100 basis points quarterly and receives 6% annually. Exhibit 15–1 illustrates the resulting debt service stream. The package combining the 6% note and the swap is equivalent to a floating-rate note paying LIBOR + 100 basis points. A floating-rate note could thus be characterized as a structured note that combines a conventional fixed-rate note and a conventional pay-floating-receive-fixed interest-rate swap. (Similarly, this basic relationship implies that a fixed-rate note could be characterized as a conventional floating-rate note plus a conventional pay-fixed-receive-floating interest-rate swap.) This simple intuition underlies all structured notes, which differ in their complexity owing to the nature of the derivative instrument(s) employed in structuring the note.

EXHIBIT 15–1

A Floating-Rate Note Can Be Characterized as a Combination of a Fixed-Rate Note and an Interest-Rate Swap

Most structured notes are issued as medium-term notes (MTNs). MTNs are usually issued under a firm’s shelf-registration program, which permits the issuer to register an inventory of securities that may be sold for two years after the registration statement’s effective date. Having registered securities available allows the issuer to design and make an offering of previously registered securities in a short period of time without the need to first file a separate registration statement with the SEC. This flexibility allows issuers to respond quickly to changes in market conditions by designing and offering structured notes opportunistically to take advantage of favorable funding opportunities.

Another advantage of MTNs is their flexibility in design, which can benefit both issuers and investors. By combining MTNs with derivatives, issuers can reduce their financing costs, while investors can satisfy their specific investment needs. Investors seek to satisfy their investment needs through reverse inquiry: They contact an investment bank to request notes with specific characteristics that may not be available currently in the market. Based on an investor’s view concerning future market conditions, such as future movements in interest rates, currency exchange rates, commodity prices, or other market variables, investors and issuers can customize structured notes to reflect the investors’ specific views on the market. Consequently, structured notes can be issued with a range of embedded options, including call options, put options, swaps, caps, floors, or collars.

Investors prefer to have an MTN issuer of high-investment-grade quality so as not to incur significant credit risk. Structured note investors target specific financial risks they are willing to incur, and they are willing to take on issuer credit risk only if that risk is the specific one they have targeted. CLNs, which are discussed later in this chapter, are a form of structured note that offers such an opportunity.

The structured note issuer usually is not willing to take on the added financial risk associated with the embedded derivative. When selling a structured note, the issuer typically simultaneously enters into one or more derivative transactions to hedge this risk by transforming the cash flows that the issuer is obligated to make to investors. These derivative transactions allow the issuer to eliminate its exposure to the risks arising from the customization of the structured notes. Returning to our floating-rate note example, the issuer who sells a floating-rate MTN that pays LIBOR plus a premium can simultaneously enter into an interest-rate swap transaction in which it pays a fixed rate of interest and receives LIBOR from a swap counterparty. By combining a floating-rate note and a swap transaction, the issuer is able to create a synthetic fixed-rate note and eliminate its floating-rate risk exposure because the floating-rate payments are offsetting.

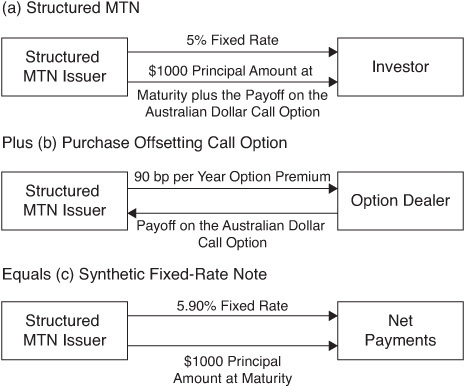

Issuing structured notes can enable a firm to reduce its financing costs when the purchasers of the structured notes are willing to pay a premium (accept a reduced yield) in exchange for the investment opportunity. They may be willing to pay a premium when similar investment opportunities are not currently available, possibly due to investment restrictions. For example, suppose an institutional investor that is not permitted to purchase stand-alone non-U.S. currency options has a view that the Australian dollar is going to appreciate significantly relative to the U.S. dollar over the next five years. It cannot buy Australian dollar call options but it might be able to purchase a structured note that will pay an increased redemption amount at maturity if the Australian dollar has appreciated above some specified threshold. This contingent payment structure embeds a call option on the Australian dollar in the structured note, as illustrated in Exhibit 15–2. The institutional investor is willing to pay for the embedded call option by accepting a lower coupon rate on the structured note than it would require for a plain vanilla fixed-rate note of the same maturity for the same issuer.

EXHIBIT 15–2

Structured Note with an Embedded Foreign Exchange Call Option

Suppose the structured note issuer does not wish to be exposed to Australian dollar foreign exchange risk. It can purchase a matching call option on the Australian dollar from an options dealer (possibly the same dealer who created the structured note) and finance the option premium through the dealer, for example, by paying the dealer 90 basis points per year. If the annual option premium payment is less than the differential in yield between the structured note and an otherwise identical conventional note, then this difference in payments reduces the firm’s funding cost, as illustrated in Exhibit 15–3. The issuer saves 10 basis points (6.00% to 5.90%) in this example.

EXHIBIT 15–3

Structured Note Issuer Reduces Its Funding Cost When It Enters into an Offsetting Derivative Transaction that Costs Less than the Value It Receives for Including the Embedded Call Option in the Structured MTN

Structured European Medium-Term Notes

When an MTN is issued outside the United States, particularly in the Euromarket, the product is called a Euro-MTN. Euro-MTNs are not subject to national regulations, such as SEC registration requirements. An issuer of Euro-MTNs typically maintains a standardized single document that can be tailored to suit almost any Euro-MTN issue and provides flexibility in the size, currency, and contingent structure of the offering. Similar to MTNs issued in the U.S. market, structured Euro-MTNs can provide an issuer with the opportunity to reduce its funding costs by crafting structured notes opportunistically.

The maturity of Euro-MTNs are typically less than five years, and the ratings on Euro-MTNs are typically higher than MTNs issued in the U.S. market because of the greater credit sensitivity of Euro-MTN investors. The Euro-MTN market is more diverse than the U.S. MTN market, mostly because it has a broader range of currency denominations and a more international mix of borrowers and investors.

Types of Structured Notes

Structured notes have been designed to provide exposure to a wide range of financial risks, such as changes in interest rates, foreign exchange rates, stock prices, the value of market indices, commodity prices, and credit quality. A few examples will illustrate the rich variety of structured MTNs.

Inverse Floating-Rate Notes

A floating-rate note is structured to facilitate taking a view on the future direction of interest rates. Inverse floating-rate notes (IFRNs) reverse the direction of the bet on interest rates. They can also be structured so as to leverage the bet. In particular, IFRNs have a coupon reset formula in which LIBOR is subtracted from a fixed percentage rate. As LIBOR increases (decreases), the coupon payment on an IFRN decreases (increases). By design, investors in IFRNs generally expect interest rates to fall and are therefore bullish on bond prices. For this reason, IFRNs have also become known as bull floaters.

If an investor expects interest rates to fall, the investor can approach an investment bank for an opportunity to purchase a structured note, issued by an investment-grade company, with coupon payments that move inversely to LIBOR. The investment bank then communicates this interest to prospective note issuers to whom it proposes an IFRN transaction. If an issuer agrees to the proposed transaction, it would then issue the IFRNs to satisfy the investor’s demand.

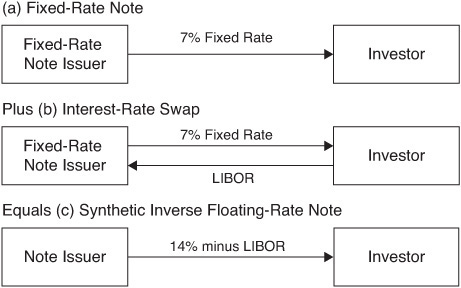

Exhibit 15–4 provides an example of an IFRN. An IFRN can be created by adding an interest-rate swap to a fixed-rate MTN. For example, if the issuer combines a 7% fixed-rate note and a fixed-for-floating interest-rate swap that pays 7% fixed and receives LIBOR, the resulting structured note pays interest at a rate equal to 14% minus LIBOR. The coupon rate on the IFRN varies inversely with LIBOR.

EXHIBIT 15–4

An Inverse Floating-Rate Note Can Be Characterized as a Combination of a Fixed-Rate Note and an Interest-Rate Swap

IFRNs have a very long duration. When interest rates drop, the coupon rate on the notes increases and the discount rate at which the stream of debt service payments is valued decreases, which magnifies the price increase. The opposite occurs when interest rates rise. Consequently, the IFRN exhibits much greater price sensitivity in response to interest rate changes than even a conventional fixed-rate note of the same maturity. As Exhibit 15–4 suggests, an IFRN has a duration that is roughly double the duration of a comparable fixed-rate note.

The issuer’s objective in issuing structured notes is to reduce its funding cost by satisfying an investor’s demand for a particular structure without incurring undue additional risk. If the issuer of IFRNs does not want to pay floating-rate interest, which will fluctuate inversely to market interest rates, but rather, wants to fix its interest payments, then it must hedge this risk. To protect itself against the IFRN’s heightened interest-rate risk, the IFRN issuer can simultaneously enter into an offsetting interest-rate swap transaction to pay floating and receive fixed.

Suppose it can issue three-year IFRNs that pay 13.75% minus LIBOR with a semiannual reset. The 25-basis-point saving versus the coupon in Exhibit 15–4 might reflect the reduction in yield purchasers are willing to accept in return for the IFRN investment opportunity. An interest rate floor is included in the IFRN to prevent a negative coupon rate if LIBOR rises above 13.75%. The swap does not have such a feature but the IFRN issuer can offset the IFRN floor by purchasing a cap contract. Thus, the IFRN issuer can hedge its IFRN risk exposure by entering into a swap transaction in which it receives a fixed rate of 7% semiannually for three years and pays LIBOR and simultaneously purchasing a cap contract that pays the excess above the strike rate if LIBOR rises above 13.75%. Suppose the cap contract costs 10 basis points per year. Exhibit 15–5 illustrates the effect of the hedging transactions. As a result of issuing the IFRN and entering into the swap and purchasing the cap contract, the issuer creates a synthetic fixed-rate note paying a 6.85% coupon rate. Its cost of arranging three-year fixed-rate funding is 6.85%, which represents a saving of 15 basis points (6.85% versus 7%).

EXHIBIT 15–5

An Issuer of an Inverse Floating-Rate Note Can Offset Its Interest-Rate Risk by Entering into an Offsetting Interest-Rate Swap and Purchasing a Cap Contract

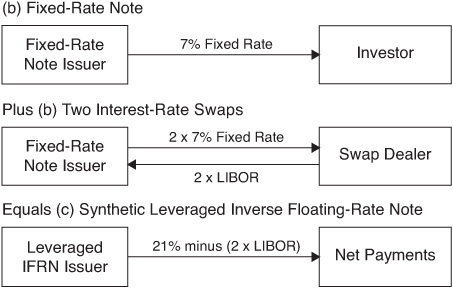

Leveraged Inverse Floating-Rate Notes

An IFRN can be leveraged by adding another interest-rate swap. This structure results in a coupon rate that is equal to some fixed rate minus some multiple of the reference rate. Exhibit 15–6 illustrates the structure of a leveraged inverse floating-rate note (leveraged IFRN). In this particular example, two interest-rate swaps are embedded in the structured note. As a result, a multiple of two is applied to LIBOR, and the coupon rate of the leveraged IFRN declines twice as fast as the coupon of the IFRN in Exhibit 15–4 as LIBOR rises. The leveraged IFRN pays interest at the rate of 21% minus two times LIBOR.

EXHIBIT 15–6

A Leveraged Inverse Floating-Rate Note Created by Combining a Fixed-Rate Note and Two Interest-Rate Swaps

Range Floating-Rate Notes

A range floating-rate note enables the issuer and investors to take a particular view on future interest rate volatility. Range floating-rate notes make interest payments only when the specified interest rate, usually a short-term interest rate such as three-month LIBOR, stays within the stated range. For instance, suppose an issuer sells a range floating-rate note that accrues interest during the first two interest periods at a rate equal to three-month LIBOR plus 100 basis points on those days when three-month LIBOR is between 3% and 4%. The range typically steps up in subsequent periods. If three-month LIBOR is outside the specified range, no interest accrues that day. Therefore, the investor profits if short-term interest rates rise in a gradual and predictable pattern and stay within the specified range. At the same time, the investor bears the risk that LIBOR rises or falls outside of the specified range. In return, the investor is compensated for this risk by receiving a greater spread over LIBOR than a conventional floating-rate note the same issuer would provide.

An issuer of range floaters could simultaneously enter into an interest-rate swap transaction to hedge its floating interest-rate risk exposure. For example, suppose the issuer enters into an interest-rate swap that pays 6% fixed and receives floating-rate payments that mirror the coupon payments on the structured note, which is three-month LIBOR plus 100 basis points when LIBOR is within the specified range, as in the previous example. As a result of the combined transactions, the issuer of the range floater locks in a financing rate of 6%, which is beneficial if its cost of conventional fixed-rate funding for that maturity exceeds 6%.

Currency-Linked Notes

A currency-linked note is a structured note in which payments are linked to the performance of a specified foreign exchange rate or a basket of currencies. Investors are able to capitalize on their view of the likely movement of the exchange rate. One of the most popular types of currency-linked notes combines a fixed-rate note with an embedded currency call or put option. The issuer pays (receives) an option premium to (from) investors in the form of an enhanced (reduced) coupon rate if it is long (short) the embedded option. At maturity, if the currency option remains out-of-the-money, the issuer repays the par amount to the investor. If the option is in-the-money, the principal repayment amount is enhanced or reduced according to the type of option and its moneyness.

For example, suppose a financial institution wants to issue a structured note that will provide a hedge against a possible fall in the value of the Japanese yen relative to the U.S. dollar. It can sell investors a Japanese-yen-linked U.S. dollar-denominated structured note for $10 million with an embedded long yen put option that specifies a strike rate set equal to the spot yen-dollar exchange rate of, say, ¥90/$1 at the time of issue. This put option on yen can be viewed equivalently as a call option on the U.S. dollar. The note pays the par amount in dollars at maturity if the option is out-of-the-money (Japanese yen remains above—equivalently, the U.S. dollar remains below—¥90/$1). At maturity, if the Japanese yen has weakened (equivalently, the U.S. dollar has strengthened) to ¥95/$1, then the payment is reduced by $0.53 million (= $10 million × (90 – 95)/95). Thus, the financial institution pays—and the investors receive—$9.47 million. The $0.53 million saving would offset part of the foreign exchange loss on the assets the financial institution had hedged by issuing the currency-linked note. Conversely, non-U.S. investors who believe that the Japanese yen would strengthen relative to the U.S. dollar—equivalently, that the U.S. dollar might weaken against the Japanese yen—could express that view by taking the other side of the transaction.

As with other structured notes, an issuer of a currency-linked note that is not interested in the currency option for hedging or investment purposes, but is merely acting as a conduit, can hedge itself by taking an offsetting position in the option. If the issuer of the currency-linked note in the preceding example, which is the buyer of a currency put option, were instead merely acting as a conduit, it could hedge itself by selling an identical (or substantially similar) yen put option to neutralize its risk exposure to changes in the yen-dollar exchange rate.

Equity-Linked Notes

Equity-linked notes are structured by combining a note with an equity derivative. The payments on an equity-linked note are principally determined by the return on the underlying equity derivative, which could be a single stock, a basket of stocks, or an equity index.

One structure combines a non-interest-bearing note and an equity call option. On the maturity date, an investor receives the par value of the note plus a variable return based on the percentage change in the underlying equity derivative. Specifically, the final payout is calculated as the initial investment times the gain or loss in the underlying stock or equity index times a note-specific participation rate. For instance, if the gain on the underlying stock or equity index is 30% during the investment period and the participation rate is 90%, the investor receives 1.27 times the amount she invested. If the note provides principal protection (a floor rate of return of zero) and the underlying equity declines or remains unchanged during the investment period, then the investor simply receives the original amount she invested.

Equity-linked notes can also be interest-bearing. In that case, the participation rate is reduced to reflect the income provided by the interest payments. As with other structured notes, an issuer of an equity-linked note can hedge its risk exposure, in this case by simultaneously purchasing an equity call option to hedge its exposure to a rise in the price of the specified stock or equity index. Issuers of equity-linked notes have typically been broker-dealers, who can structure these hedges relatively cheaply.

Commodity-Linked Notes

Commodity-linked notes are created by combining a note with a commodity derivative. Commodities that have served as the underlying for such securities include crude oil, natural gas, gasoline, copper, lead, or precious metals. The payments on a commodity-linked note are determined by the performance of the underlying commodity or a specified basket of commodities. Interest or principal payments or both can be commodity-linked.

One structure combines a non-interest-bearing note and a commodity call option. At maturity, an investor receives the par value of the non-interest-bearing note plus a variable return based on the percentage change in the price of the underlying commodity component. If the note provides principal protection and the price of the underlying commodity declines or remains unchanged during the investment period, then the investor simply receives the original amount she invested.

As with equity-linked notes, commodity-linked notes can also be interest-bearing, and the issuer of the notes can hedge its risk exposure by simultaneously entering into an offsetting commodity derivative transaction.

Risks of Structured Notes

Issuers of structured notes and investors face a variety of risks in addition to the risk that is specific to the embedded derivative instrument.

Credit Risk

Because a structured note combines a plain vanilla note and a derivative instrument that an investment bank creates to satisfy an investor’s desire for exposure to a specific risk, an investor bears the risk that the issuer might default on the note. Investors try to control this risk by limiting their structured note purchasers to notes issued by high-grade issuers, such as the government-sponsored enterprises Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae before they encountered financial distress.

It has been very common, however, for investment banks to issue structured notes. Because of the risk of issuer default, it is possible for a structured note to become worthless even when the embedded derivative is in-the-money. This counterparty risk is well illustrated by the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, which resulted in Lehman Brothers structured notes becoming worthless even when the underlying derivatives had positive returns. In effect, the default risk trumped the risks and returns inherent in the embedded derivative instrument and nullified the specific bet that the issuer and the investors were trying to make when the structured notes were issued.

Market Risk

By design, an investment in a structured note carries additional market risks on top of the risks that a traditional note carries because of the embedded derivative instrument. A structured note is created for investors who are seeking to profit from specific market risks. Depending on future market conditions, such as interest-rate movements, stock price movements, or commodity price movements, losses on a structured note could be magnified. Market risks can be quantified with financial models, such as an interest-rate term structure model or an option pricing model, so that the degree of market risk can be quantified and priced into the structured note price.

Liquidity Risk

The markets for structured notes are generally less liquid than those for conventional notes. Most structured notes are rarely traded after issuance. One of the reasons for the market illiquidity is that because a structured note is customized to satisfy the specific needs of an original investor, there is a smaller number of potential investors who might be willing to buy the structured note (and make the same customized bet) in the secondary market. Another reason for the market illiquidity is that the issue sizes are generally smaller and the transaction costs are usually higher than for standardized notes. Consequently, to value a structured note, one needs to take into account not only the credit risk of the issuer, but also the particular risk/return profile customized to the investor. Pricing accuracy can be another concern with structured notes. Because structured notes are rarely traded after issuance, their prices are usually calculated with a financial model. In that case, the accuracy of the valuation depends to a large extent on whether the underlying derivative is modeled correctly.

As a result, when an investor intends to sell structured notes before they mature, it may not be easy to sell them at a reasonable price within a reasonable time frame. For instance, if interest rates move in the opposite direction to an investor’s expectation when he purchased a structured note, the investor may want to sell the structured note but not be able to find a market for it. As another example, when an investor’s view on the direction of interest rates proves to be correct but the interest rate underlying the structured note (such as the interest rate in an inverse floater) changed earlier than expected, the investor may want to sell the structured note before the maturity date to take advantage of current market conditions and lock in her profit. Because structured notes are thinly traded securities, the spread between the market bid and ask prices may be wide; the size of the spread would reduce the profit realized on the structured note investment.

Systemic Risk

Systemic risk refers to the risk associated with a broad market disruption within the financial market system, as opposed to being limited to an individual security or a particular market segment. By design, structured notes are more exposed to systemic risk than conventional notes because the payments on structured notes are often tied to the conditions in the derivative markets for foreign exchange, equities, or commodities. Any disruptions or problems in the underlying derivative market would magnify the structured note holder’s risk exposure to that market and compound her risk exposure to disruptions or problems in the fixed income market.

Why Do Investors Buy Structured Notes?

Investors buy structured notes when the risk/return profile of the security matches their investment needs and the investment opportunity is not otherwise available as cheaply (or at all) in the capital market.

Administrative Efficiency

Compared with separate transactions consisting of notes and derivative instruments, which could be complex and costly, purchasing a structured note makes the process simple and reduces administrative costs, such as the cost of maintaining margin or the cost of rolling over shorter-term derivative contracts.

Diversification and Hedging

Structured notes facilitate investors diversifying their investment portfolios into new products and new security types and possibly new markets. The embedded derivative can serve a useful hedging purpose, as in the example earlier in the chapter of a financial institution that issued a structured currency-linked note containing a Japanese yen put option to protect against a fall in the value of the Japanese yen relative to the U.S. dollar.

Customization and Managing Risk Exposure

Because structured notes are customized to conform to investors’ views on the interest rate, stock price, exchange rate, or commodity price reflected in the underlying derivative instrument, investors are able to adjust the risk/return profiles of their investment portfolios. Through a reverse inquiry, an investor is able to request notes with specific characteristics, which may not be available currently in the market.

Some structured notes are created to minimize risk exposure by providing principal protection, while others are created to maximize returns with or without principal protection. In any case, the derivative components of the structured notes allow the products to be aligned with any particular investor’s market view or economic forecast and to suit the investor’s risk tolerance. Moreover, leverage can be built into structured notes, as with leveraged inverse floaters, which can enhance expected returns—but also investment risk—as compared with a direct investment in the underlying assets. Therefore, investors are able to manage risks appropriate to their risk/return profiles in line with their views on the market.

Principal-Protected Structured Notes

A principal-protected structured note (PPN) is a structured note that guarantees the return of at least 100% of invested capital (a floor rate of return of zero), regardless of market conditions, as long as the notes are held to maturity. On the maturity date, barring a default by the issuer, investors receive payments consisting of the original principal amount plus any gains from the underlying assets. Because a PPN is a structured note combined with downside protection, investors in PPNs exchange more certain yet potentially lower returns for more uncertain and potentially larger returns. The return from investing in a PPN depends on the value of the embedded option at maturity. With many PPNs, there is no periodic payment of interest during the investment period, and just a single payment is made at maturity.

Its name suggests that a PPN guarantees the repayment of 100% of invested principal. However, this assurance does not mean that there is zero downside risk because the issuer might default. Typically, an investment bank serves as the issuer and is therefore responsible for paying the contingent principal amount at maturity. Therefore, evaluating the financial condition and creditworthiness of the investment bank issuer is an important step in deciding whether to purchase a PPN. Credit risk can be significant, which materializes when the investment bank issuer defaults.

The Impact of the Lehman Brothers Bankruptcy

The Lehman Brothers collapse in September 2008 has affected virtually all areas of the financial markets in some way, but particularly the structured products market, because a large number of products were linked to Lehman Brothers’ credit. One of the more significant products was the Lehman Brothers PPNs.

The Lehman Brothers PPNs were issued as hybrid financial instruments, constructed from a combination of stocks, bonds, currencies, commodities, and derivatives, which were sold to retail investors as low-risk and safe investments. UBS, one of the largest sellers of structured notes, and other brokerage firms sold Lehman Brothers structured notes to retail investors with principal protection effectively guaranteed by Lehman Brothers. Following the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in September 2008, however, the guarantee of principal protection became meaningless, and the PPNs became essentially worthless.

Before the Lehman Brothers collapse, investment banks were able to sell PPNs to investors easily because investors were convinced that the PPNs would guarantee principal repayment even when the underlying investments did not produce a positive return. However, the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy rudely awakened retail investors to the risk of possible credit loss and generated a substantial amount of litigation in which investors asserted that the PPN guarantee had been misrepresented because the investors’ principal was not truly protected in all events.

This negative experience highlights the need to warn investors properly concerning the risks of investing in structured notes. It also highlights the problem inherent in every derivatives contract: a counterparty default will undermine the upside opportunity or downside protection investors thought they were getting when they purchased the structured notes.

CREDIT-LINKED NOTES

Broadly defined, a CLN is a structured note with at least some of its payments dependent on the occurrence of a defined credit event, such as a specified entity’s default, a change in a specified entity’s credit rating, or a change in a specified debt instrument’s credit spread. CLNs have grown in importance with the development of the market for credit default swaps (CDS) because like CDS, CLNs provide attractive opportunities for managing credit risk exposure.

Characteristics of Credit-Linked Notes

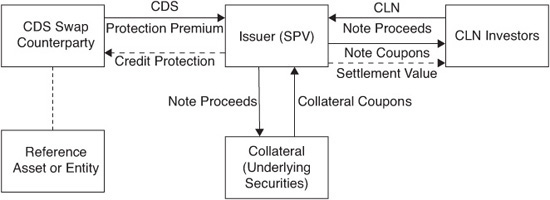

Typically, a CLN is a combination of a conventional note and a CDS. A CLN is often issued by either a very strong credit, such as a high-grade bank or a government-sponsored enterprise, or a special-purpose bankruptcy-remote trust that is a counterparty to the CDS. A total return swap or a credit forward contract can also be used in this structure. A CLN allows the issuer to transfer a particular credit risk exposure to the purchaser of the CLN. In this structure, the issuer (seller) of the CLN is the protection buyer, and the investor (purchaser) of the CLN is the protection seller, who ultimately bears the credit risk.

As shown in Exhibit 15–7, if a credit event occurs, the CLN is redeemed early. The redemption amount is reduced below the face amount according to the reduced value of the underlying reference asset, such as a bond or a bank loan that falls in value due to the credit event’s occurrence. If no credit event occurs during the life of the CLN, then the full principal amount of the note is paid to the investors at maturity.

EXHIBIT 15–7

Payoffs on a Credit-Linked Note

CLNs are attractive to issuers who want to hedge against a credit default or a rating downgrade, which would adversely affect the value of one of their investments. They are able to customize the terms of the credit protection contract to satisfy their credit risk protection objectives. On the other hand, investors purchase CLNs with the objective of enhancing the yield they receive on their note investment. Investors find CLNs attractive because they are able to gain access to the credit market, which might be unavailable to them otherwise.

A CLN normally adjusts the principal repayment to pay off on the credit derivative instrument embedded within the note. For example, suppose an investor purchased a five-year CLN at a credit spread of 200 basis points that would repay $1,000 at maturity or $1,000 minus the payoff if a credit event occurs before the CLN matures. The investor has sold a put option to the issuer of the note and in return receives a higher coupon. Suppose that the reference bond’s credit spread is 100 basis points and a credit event occurs that causes the price of the reference asset to fall to 80. The issuer of the CLN pays 100 basis points per year for the put option (200 – 100 basis points). The holder of the CLN would receive $800 (80% of $1,000) per $1,000 face amount following the credit event. The single payment is equivalent to receiving $1,000 and simultaneously paying off $200 on the put option.

Funded Credit Derivative

CLNs have gained in popularity because they provide credit protection like CDS, but entail less risk of contract default. CLNs are a form of funded credit derivative. The investor in the CLN, the protection seller, pays cash to the protection buyer—the full purchase price of the CLN—to purchase the CLN. If a credit event occurs, the protection buyer’s repayment obligation decreases, and the protection buyer returns less cash to the protection seller than if no credit event had occurred. In contrast, with CDS, the protection buyer must collect the cash payment from the protection seller, if there is cash settlement, or the protection seller must obtain the bond or loan obligation from the protection buyer and sell it in the market, if there is physical settlement. A CLN thus involves less contract default risk than a CDS written by the same protection seller.

SPV Structure

CLNs have been issued by large financial institutions. This unfunded structure exposes CLN investors to the financial institution’s default risk. Alternatively, the CLNs can be issued through a funded structure in which a bankruptcy-remote special-purpose vehicle (SPV) is created to hold high-quality financial assets and issue the CLNs. This structure, which is illustrated in Exhibit 15–8, insulates CLN investors from the risk of issuer default because the SPV’s assets are selected so as to generate sufficient cash flows to service the CLNs. The funded CLN structure thus limits the investor’s default risk exposure to the reference obligation specified in the CLN, which was the purpose for creating the CLN in the first place.

EXHIBIT 15–8

Structure of a Credit-Linked Note

Combining Credit-Linked Notes and Credit Default Swaps

An issuer can design structured products combining CLNs and CDSs to meet both the issuer’s and the investors’ requirements. Exhibit 15–9 illustrates the combined structure of CLN and CDS, which is designed to fund the CDS obligation and to provide higher returns for an investor who is willing to take on the corresponding credit risk. The CLNs are issued by an SPV, which holds the collateral securities (also known as the underlying securities). The SPV uses the proceeds from issuing the CLNs to purchase the pre-agreed collateral securities. They are normally risk-free securities, such as Treasury bills. The SPV grants a security interest in the collateral to secure the SPV’s future performance under the CLN contract. The cash flow from these high-quality securities is used to pay the interest and principal on the CLNs as long as no credit event occurs. In this structure, the SPV buys credit protection on a single reference asset or entity by entering into a CLN and paying the ongoing premium, which is included in the CLN interest rate. The CLN investors sell the credit protection and receive the premium; they have the credit risk exposure to the reference asset or entity.

EXHIBIT 15–9

CLN and CDS Structure on a Single Reference Name

At the same time, the SPV simultaneously enters into a CDS agreement with a highly rated swap counterparty. In this swap agreement, the SPV sells credit protection on the same reference asset or entity underlying the CLNs and, in return, receives the CDS premium. Through the combined CLN and CDS structure, the SPV has a neutral credit risk position with respect to the reference asset or entity.

The coupon rate on the CLN is a spread over LIBOR and is funded by the collateral securities and the fee generated by selling protection in the CDS transaction. The SPV’s payment on the CLN is linked to the performance of the reference asset or entity. If a specified credit event1 involving the reference asset or entity occurs, there are three options to settle the CLN and the CDS. First, under the recovery-linked option, a third party sells the reference assets into the market, and the SPV distributes the realized proceeds to the CLN investors to settle the CLN. At the same time, the third party sells the underlying collateral securities and distributes the proceeds to the swap counterparty to settle the CDS. Second, under the physical delivery option, the CDS swap counterparty delivers the reference assets to the SPV and the SPV delivers them to the CLN investors, and the SPV also delivers the underlying collateral securities to the CDS swap counterparty. Third, under the binary option, a specified cash payment is negotiated among the SPV, the CDS counterparty, and the CLN investors at the outset of the transactions. The SPV makes that cash payment to the CDS counterparty if a credit event occurs. It then deducts it from the principal amount owed to the CLN investors and repays the net amount to the CLN investors.

Reference Obligation Is Emerging Market Sovereign Debt

In the case of CLNs, in which the reference obligation is an emerging market debt obligation, the SPV also may need to enter into an interest-rate swap or a currency swap to reduce interest-rate risk and to tailor the required cash flows of the CLN to the cash flows of the collateral. The resulting package is a CLN that performs similarly to a sovereign bond. Such CLNs are bought by investors who seek an increase in yield as compared with what a comparable sovereign bond would offer and who do not need liquidity during the life of the CLN.

Credit-Sensitive Notes

A conventional corporate bond can be viewed as a package consisting of a long Treasury note and a short position in a CDS, with the credit event defined as an actual default with immediate payment. (Alternatively, one can assume the immediate sale of the note in the event default occurs and ignore the optionality inherent in the flexibility to time the sale of the defaulted note.) In a conventional corporate bond, part of the coupon payment (the credit spread) can be viewed as the CDS premium. The size of the coupon payment depends on the credit quality of the bond at the date of issue, but normally does not change if the credit quality of the bond subsequently changes. Credit-sensitive notes provide for variation in the size of the coupon if the issuing firm’s credit quality changes.

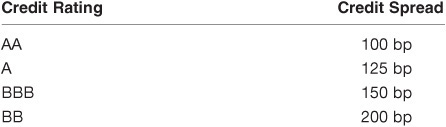

A credit-sensitive note is a fixed- or floating-rate note on which the interest rate is adjusted in response to a change in the issuer’s credit rating. The coupon rate adjusts inversely to the change in the note’s credit rating. If the issuer is downgraded by a credit rating agency, the credit-sensitive note pays a higher coupon rate to compensate investors for the additional credit risk. In this structure, the investors are short a credit spread forward agreement.

Consider the following example with the indicated credit ratings and spreads:

An investor buys a single-A-rated note paying 125 bp over Treasuries. If the credit rating rises to AA, the investor receives 25 bp less per year in interest. If the credit rating falls to BBB, the investor receives 25 bp more per year in interest. Thus, a credit-sensitive note is a form of structured note, which provides a built-in hedge against changes in the issuer’s credit quality. It thus provides protection against the moral hazard risk fixed income investors face.

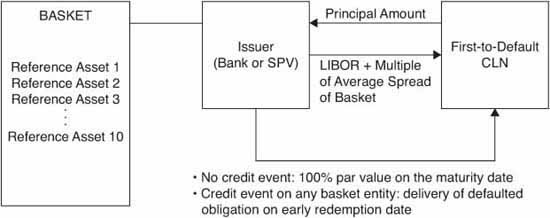

First-to-Default Credit-Linked Notes

A standard CLN is issued with reference to one specific bond or loan. A basket credit-linked note is a CLN that is linked to more than one reference entity. In a first-to-default CLN, an investor sells credit protection on a basket of assets, and the payment occurs upon whichever entity in the basket is the first to default. The coupon payment on the first-to-default CLN is LIBOR plus a multiple of the average spread for the reference entities in the basket of assets. As soon as a credit event occurs on any of the reference assets, the CLN matures.

Exhibit 15–10 illustrates a typical first-to-default CLN structure. Suppose an issuer sells a first-to-default CLN at par with three years to maturity, which is linked to a basket of 10 reference assets with a face value of $10 million. An investor who purchases the note pays $10 million to the issuer at the closing. The issuer will pay interest during the life of the note and will repay the $10 million at maturity, subject to there being no credit event. The CLN investor takes a credit position equal to $10 million notional in each reference entity. The first time a credit event occurs on any asset in the basket, the issuer redeems the CLN by delivering to the CLN investor $10 million face amount of the reference asset that experienced the credit event. Typically, the actual redemption amount is determined by the market value, not by the recovery value, of the reference obligation at the time the credit event is verified.

EXHIBIT 15–10

Structure of a First-to-Default Credit-Linked Note

A first-to-default CLN investor faces the same type of credit risk exposure on default as with a standard CLN, namely, the reduced recovery rate on the defaulted credit. Because a first-to-default CLN involves multiple assets in the basket, rather than a single asset as in a standard CLN, it can reduce the investor’s default risk exposure as compared with a single-name CLN through credit risk diversification. The CLN investor obtains default risk exposure to a basket of reference entities, which can be diversified across industries and also across credit rating categories. This diversification benefit is greater the lower are the pairwise correlations among the returns on the reference entities in the basket.

Emerging Market Credit-Linked Notes

Emerging market CLNs are structured notes that are tied to the creditworthiness of a relatively lower-rated sovereign credit. Demand from investors who are seeking higher returns from emerging market CLNs has increased over the past few years, as growth prospects for the emerging economies have improved due to the world economy recovering from the 2007–2009 financial crisis. To compensate emerging market CLN investors for taking on greater counterparty credit risk as well as liquidity risk, they are typically paid more than the underlying debt yield. For example, an investment bank issues a $10 million 10-year 9.5% note linked to Turkish government debt when Turkish government bonds of the same maturity pay 9%.

Emerging market CLNs are efficient investment instruments for investors who are not able to trade the underlying bonds of the countries for any reason, such as transaction costs, investment regulations, or other market frictions. They are attractive to emerging market fixed income investors who believe that a particular sovereign credit rating is likely to be upgraded and who want an investment opportunity that enables them to express that view.

Synthetic CDO Credit-Linked Notes

Synthetic collateralized debt obligations (SCDOs) are a form of CDO that invests in CDSs or other assets to gain exposure to a fixed income portfolio. Unlike a CDS, which typically references a single asset, an SCDO references a portfolio of assets. This portfolio is securitized by issuing notes that are divided into tranches. The SCDO notes are typically prioritized sequentially as to their default risk exposure to the underlying portfolio. They also typically have a sequential amortization structure; the most senior notes are scheduled to be fully repaid first, the next most senior notes are scheduled to be fully repaid next, and so on. Accordingly, when payments are made, they flow first to the most senior notes, thus amortizing them more quickly than the subordinated notes. Investors in the SCDO tranches are able to take on credit risk in accordance with their risk tolerances by purchasing a particular note tranche.

Sponsors may combine SCDOs and CLNs to reduce counterparty risk. Like other CLN structures, an SPV is created to provide a bankruptcy-remote depository for the high-quality assets that are purchased with the CLN proceeds. Exhibit 15–11 illustrates a hybrid structure that combines SCDOs and CLNs in a fully funded structure. The SPV sells credit protection to the sponsor; this credit protection is ultimately provided by the CLN investors. If a credit event occurs involving any of the reference assets, the payments to the CLN investors are reduced according to the repayment priorities of their respective notes. The first loss CLN investors suffer the initial loss up to the full amount of their principal before more senior CLNs are affected.

EXHIBIT 15–11

Funded SCDO: SCDO Combined with CLNs

SCDO transactions can also be structured as a hybrid that blends the funded and unfunded structures. A single, highly rated investor purchases the most senior tranche in the form of an unfunded CDS, whereas the rest of the liability structure is divided into a series of funded CLN tranches, which are purchased by various investors according to their relative risk tolerances. The funded portion of this SCDO structure would mirror the structure illustrated in Exhibit 15–11.

KEY POINTS

• Structured notes and CLNs provide customized interest or principal payments that depend on the performance of a specified reference asset, market price, index, interest rate, foreign exchange rate, commodity price, or some other market quantity.

• A structured note combines a conventional fixed- or floating-rate note with an embedded derivative instrument.

• A CLN is a particular form of structured note in which the derivative instrument is a credit default swap or some other form of credit derivative.

• The issuer’s objective in issuing structured notes is to reduce its funding cost by satisfying an investor’s demand for a particular structure without incurring undue additional risk.

• Investors buy structured notes when the risk/return profile of the security matches their investment needs and the investment opportunity is not otherwise available as cheaply (or at all) in the capital market.

• The financial crisis of 2007–2009 resulted in a reduction in the issuance of structured notes and CLNs. Issuance of both began to recover as the crisis passed. Issuance of these fixed income instruments should increase as fixed income market participants take advantage of the opportunities they afford to optimize their investment portfolios.