CHAPTER

THIRTY

STRIPPED MORTGAGE-BACKED SECURITIES

Managing Director

Morgan Stanley

and

Adjunct Professor

New York University

GARY LI

Senior Vice President

HSBC

TODD WHITE

Managing Director

Columbia Management Investment Advisors, LLC

DAVID KWUN

Managing Director

HSBC

In 1983, Freddie Mac launched the collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO) structure that enabled issuers to tailor-make mortgage securities according to investor coupon, maturity, and prepayment risk specifications. In July 1986, Fannie Mae introduced a new addition to the mortgage security product line—stripped mortgage-backed securities (SMBS). In this chapter we will discuss the particular investment characteristics of SMBS and how they can be used in various investment and hedging strategies by different market participants.

By redistributing all or portions of the interest and/or principal cash flows from a pool of mortgage loans to two or more SMBS classes, Fannie Mae developed a new class of mortgage securities that enabled investors to take strong market positions on expected movements in prepayment and interest rates. As the mortgage pass-through securities market matured, the number of derivative products available increased to give investors a broad range of choices to help them achieve their investment goals. In addition to straight interest-only (IO) securities, and principal-only (PO) securities, investors may now choose from a wide array of synthetic coupons from each strip issue. Investors are able to fine-tune their derivatives to match their desired sensitivity to interest rate, prepayment, and market risk.

The authors would like to thank Julia Kadiogu for her insightful comments.

SMBS are highly sensitive to changes in interest rate and prepayment speeds and tend to display asymmetric returns. SMBS certificates that are allocated all or large proportions of underlying principal cash flows tend to display very attractive bullish return profiles. As market rates drop and prepayments on the underlying collateral increase, the return of these SMBS will be greatly enhanced since principal cash flows will be returned earlier than expected. Conversely, SMBS that are entitled to all or a large percentage of the interest cash flows have very appealing bearish return characteristics since greater amounts of interest cash flows are generated when prepayments of principal decrease (typically when market rates increase).

The asymmetric returns of SMBS appeal to a broad variety of investors. SMBS can be used effectively to hedge interest rate and prepayment exposure of other types of mortgage securities, such as certain types of CMO bonds and premium-coupon mortgage pass-through securities. Combined with interest rate derivatives, SMBS is also a typical instrument for mortgage servicers to hedge the interest rate and prepayment exposure of the mortgage servicing rights. Thrift institutions and mortgage bankers often use PO securities to hedge their servicing portfolios or use IO securities as a substitute for servicing income. SMBS can also be combined with other fixed income securities such as U.S. Treasuries and mortgage securities to enhance the total return of the portfolio in varying interest rate scenarios. Insurance companies and pension funds frequently use SMBS as a method of tailoring their investment portfolio to meet the duration of liabilities and thus minimize interest rate risk. SMBS are used by various types of investors to accomplish their investment objectives. Insurance companies, pension funds, money managers, hedge funds, and other total rate of return accounts use SMBS to improve the return of their fixed income portfolios.

OVERVIEW OF THE SMBS MARKET

The SMBS market has grown substantially since the introduction of the first SMBS in July 1986. In total, an estimated $522 billion agency SMBS in 603 issues have come to market as of December 2010. Fannie Mae has been the predominant issuer of SMBS with 417 issues totaling $328 billion.

Types of SMBS

Strip securities exist in various forms. The first and earliest type of mortgage strip securities is called synthetic-coupon pass-through securities. Synthetic-coupon pass-through securities receive fixed proportions of the principal and interest cash-flow from a pool of underlying mortgage loans. These securities were introduced by Fannie Mae in mid-1986 through its “alphabet” strip program.

Trust IOs and Trust POs, the second and most common type of mortgage strip securities, were introduced by Fannie Mae in January 1987. IOs and POs receive, respectively, only the interest or only the principal cash-flow from the underlying mortgage collateral. Fannie Mae (FNMA) and Freddie Mac (FHLMC) Trust IO/PO SMBS represent the major issuance and trading activities in the SMBS market. A liquid and dynamic secondary market in conjunction with the agency to-be-announced (TBA) market has been established to allow quick and frequent transactions. Benchmark bonds in the sector (large in size and most liquid issues) enhanced liquidity and investor pricing transparency.

A third type of strip security, the CMO strips (also called structured IOs and POs) are also popular among issuers and investors. As implied by their name, structured IOs and POs are tranches within a CMO issue that receive only principal or interest cash flows or have synthetically high coupon rates.

Development of the Agency SMBS Market

The First Mortgage Strip—FNMA SMBS “Alphabet” Strip Securities

Fannie Mae pioneered the first stripped mortgage security in July 1986 through its newly created SMBS Program. For each issue of SMBS Series A through L, Fannie Mae pooled mortgage loans that had been held in its portfolio and issued two SMBS pass-through certificates representing ownership interest in proportions of the interest and principal cash flows from the underlying mortgage loan pools. Alphabet strips were subsequently called synthetic discount- and premium-coupon securities since the coupon rate of the alphabet strip was quoted as the percentage of the total principal balance of the issue. For example, a strip that receives 75% interest and 50% principal of the cash-flow from a FNMA 10% would be a synthetic 15% coupon security since the 7.50% coupon is expressed as a 100% principal (i.e., 7.50% coupon/50% principal = 15% coupon/100% principal). By the same logic, a strip security from a FNMA 10% that receives 50% interest and 1% principal would be a 5,000% coupon security.

The FNMA SMBS Trust Program and IOs and POs

The successive and current FNMA strip program, the SMBS Trust Program begun in 1987, provided a vehicle through which deal managers (e.g., investment banks) can swap FNMA pass-through securities for FNMA SMBS Trust certificates. In the swapping process, eligible FNMA pass-through securities submitted by the deal managers are consolidated by Fannie Mae into one FNMA Megapool Trust. In return, Fannie Mae distributes to the deal manager two similarly denominated SMBS certificates evidencing ownership in the requested proportions of that FNMA Megapool Trust’s principal and interest cash flows.

To date, the majority of FNMA SMBS Trusts have contained IO and PO securities. IOs and POs represent the most leveraged means of capturing the asymmetric performance characteristics of the two cash-flow components of mortgage securities. Although IOs and POs can be combined in different ratios to create synthetic-coupon securities, some investors have shown a preference for one-certificate synthetic securities due to their bookkeeping ease. In late 1993, FNMA added another feature to its SMBS structure. In addition to IO and PO classes, FNMA SMBS Trusts contained a provision for exchanging IOs and POs for another class with a synthetic coupon. The synthetic-coupon classes that are available are determined in the prospectus supplement for each Trust and generally range from 0.5% to double the coupon on the underlying collateral in 50 basis point increments. Exchanges are executed for a small fee and may be reversed back into IO and PO components as well as into any other available combination, provided the proportions of IO and PO are correct. To promote liquidity in the SMBS market, all FNMA SMBS certificates (except FNMA SMBS Series L) have a unique conversion feature that enables like denominations of both classes of a FNMA SMBS issue or Trust to be exchanged on the book-entry system of the Federal Reserve Banks for like denominations of FNMA MBS certificates or Megapool certificates. Because of the potential for profitable arbitrages, the aggregate price of the two classes of any same FNMA issue or Trust tends to be slightly higher (the “recombo premium”) than the price of comparable-coupon and remaining-term FNMA pass-through certificates.

All FNMA SMBS pass-throughs (alphabet and Trusts) have the same payment structure, payment delays, and FNMA guarantee as regular FNMA pass-throughs.

FHLMC Stripped Giant Program

Freddie Mac is also a participant in the SMBS market. In October 1989, Freddie Mac announced the Stripped Giant Mortgage Participation Certificate (PC) Program.

Freddie Mac’s Stripped Giant Program is similar to Fannie Mae’s swap SMBS Trust Program. Deal managers submit FHLMC PCs to Freddie Mac; in turn, Freddie Mac aggregates these PCs into Giant pools and issues Strip Giant PCs representing desired proportions of principal and interest to the deal manager. All Freddie Mac Strip PCs have the same payment structure, payment delays, and payment guarantee as regular FHLMC PCs. Like Fannie Mae SMBS, Freddie Mac Giant Strip IOs and POs have a conversion feature that allows them to be exchanged for similarly denominated FHLMC PCs. Under the Freddie Mac Gold MACS (Modifiable and Combinable Securities) program, IO and PO securities may be exchanged for synthetic-coupon classes that have been predetermined in the prospectus supplement for a fee.

Ginnie Mae Collateral for SMBS

In 1990, Freddie Mac began to issue SMBS collateralized by Ginnie Mae pass-through certificates. Since the beginning of 1990, Fannie Mae has issued 76 trusts that have had underlying GNMA collateral. Freddie Mac began to issue GNMA-backed SMBS in 1993 and has issued seven GNMA strips to date. The increased availability of GNMA SMBS has further broadened the investor base of SMBS, enhanced the liquidity of the SMBS market, and increased the number of hedging alternatives available to GNMA investors.

PO-Collateralized CMOs

Profitable arbitrage opportunities led to the introduction of CMO securities collateralized by POs. PO-collateralized CMOs allocate the cash-flow from underlying PO securities between several CMO tranches with different maturities and prepayment patterns. The potential for profitable arbitrages with PO securities has enhanced the efficiency of the SMBS market by effectively placing a floor on the price potential of POs and a price ceiling on corresponding IOs in a given market environment.

CMO Strip Securities

Strip securities are included in CMO issues as regular-interest (nonresidual) CMO tranches. CMO strip securities that pay only principal, large proportions of interest cash flows (relative to principal cash flows), or only interest over the underlying mortgage collateral’s life are termed PO securities, “higher-interest” securities, IO securities, respectively; they tend to have performance characteristics similar to SMBS. Other types of CMO strip securities receive initial and ongoing collateral principal or interest in cash flows after other classes in the CMO issue are retired or have been paid. These types of strip CMO securities are structured as PO or PAC IOs, TAC IOs, or Super-POs, and perform differently from SMBS.

INVESTMENT CHARACTERISTICS

SMBS enable investors to capture the performance characteristics of the principal or interest components of the cash flows of mortgage pass-through securities. These individual components display contrasting responses to changes in interest rates and prepayment rates. PO SMBS are bullish instruments, outperforming mortgage pass-throughs in declining interest rate environments. IO SMBS are bearish investments that can be used as a hedge against rising interest rates.

Variation of Interest and Principal Components with Prepayments

The cash flows that an MBS investor receives each month consist of principal and interest payments from a large group of homeowners. The proportion of principal and interest in the total payment varies depending on the prepayment level of the mortgage pool. Exhibits 30–1 and 30–2 illustrate these cash flows for $1 million 30-year FNMA current-coupon pass-through securities at various PSA prepayment speeds.

EXHIBIT 30–1

Principal Component of Monthly Cash Flows

EXHIBIT 30–2

Total Amount of Interest Cash Flows

Exhibit 30–1 shows the principal component of the monthly cash flows. Since the interest is proportional to the outstanding balance, the exhibit can also be viewed as showing the decline in the mortgage balance at the various prepayment speeds.

At a zero prepayment level, the interest and principal cash flows in Exhibits 30–1 and 30–2 compose a normal amortization schedule. In the earlier months of the security’s life, the cash flows primarily contain interest payments. This occurs because interest payments are calculated based on the outstanding principal balance remaining on the mortgage loans at the beginning of each month. As the mortgage loans amortize, the cash flows increasingly reflect the payment of principal. Toward the end of the security’s life, principal payments make up the bulk of the cash flows.

Prepayments of principal significantly alter the principal and interest cash flows received by the investor in a mortgage pass-through security. Homeowners who prepay all or part of their mortgage loans return more principal to the investor in the earlier years of the mortgage security. All else being equal, an increase in prepayments has two effects:

1. The time remaining until return of principal is reduced as shown in Exhibit 30–1. At 100% PSA, the average life of the principal cash flows is 11.3 years, whereas at faster speeds of 200 and 300% PSA, principal is returned in average time periods of 7.6 years and 5.7 years, respectively.

2. The total amount of interest cash flows is reduced, which is shown in Exhibit 30–2. This occurs because interest payments are calculated based on the higher amount of principal outstanding at the beginning of each month, and higher prepayment levels reduce the amount of principal outstanding.

Effect of Prepayment Changes on Value

A mortgage pass-through security represents the combined value of the interest and principal cash flows. The effects of prepayments on the present value of each of these components tend to offset each other. Increases in prepayments reduce the time remaining until repayment of principal. The sooner the prepayment of principal is repaid, the higher the present value of the principal. Conversely, since increasing levels of prepayments reduce interest cash flows, the value of the interest decreases.

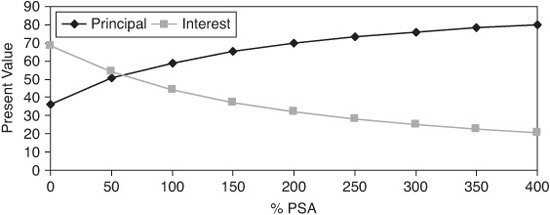

Thus, the interest and principal cash flows individually are much more sensitive to prepayment changes than the combined mortgage pass-through security. This is illustrated in Exhibit 30–3, which shows the present values of the principal and interest components of a FNMA current coupon pass-through security at various prepayment levels.

EXHIBIT 30–3

Present Values of Principal and Interest Components of FNMA Current-Coupon Pass-Through Security

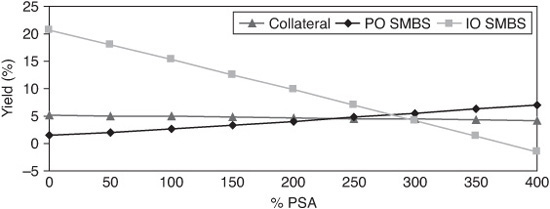

The greater sensitivity of IOs and POs to prepayment changes is further illustrated in Exhibit 30–4, which shows the realized yields to maturity (or internal rates of return) for a typical IO and PO and for the underlining collateral for given purchase prices. The IO and PO reflect sharply contrasting responses to prepayment changes; the IO’s yield falls sharply as prepayments increase, whereas the PO’s yield falls sharply as prepayments decrease. The yield of the underlining collateral is, on the other hand, relatively stable since it is assumed to be priced close to par.

EXHIBIT 30–4

Realized Yields to Maturity for Typical IO and PO

Price Performance of SMBS

The preceding discussion indicates that prepayment speeds are by far the most important determinant of the value of an SMBS. Since the price response of an SMBS to interest rate changes is determined, to a large extent, by how the collateral’s prepayment speed is affected by interest rate changes, we begin with a discussion of mortgage prepayment behavior.

The Prepayment S Curve

The prepayment speed of an MBS is a function of the security’s characteristics (such as coupon and age), interest rates, and other economic and demographic variables. Although detailed prepayment projections generally require an econometric model, the investor can obtain some insight into the likely behavior of an SMBS by examining the spread between the collateral’s gross coupon and current mortgage rates.

This spread is generally the most important variable in determining prepayment speeds. With respect to this spread, prepayment speeds have an S shape; speeds are fairly flat for discount coupons (when the spread is negative and prepayments are caused mainly by housing turnover), they start increasing when the spread becomes positive, they surge rapidly until the spread is several hundred basis points, and then they level off when the security is a high premium. At this point, there is already substantial economic incentive for mortgage holders to refinance, and further increases in the spread lead to only marginal increases in refinancing activity. This S curve is illustrated in Exhibit 30–5, which shows projected long-term prepayments for current coupon collateral for specified changes in mortgage rates.

EXHIBIT 30–5

Prepayment S Curve

In the remainder of this section, we make repeated reference to Exhibit 30–5, since the performance of an SMBS can be explained to a large extent by the position of its collateral on the prepayment S curve.1

Projected Price Behavior

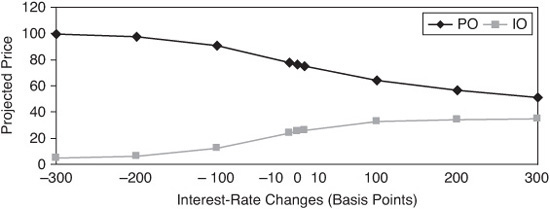

Exhibit 30–6 gives projected price paths for a current coupon IO and PO for parallel interest rate shifts.2

EXHIBIT 30–6

Projected Price Paths for a Current Coupon IO and PO for Parallel Interest Rate Shifts

The projected price behavior of the SMBS as interest rates change can be explained largely by the prepayment S curve in Exhibit 30–5.

• As rates drop from current levels, the collateral begins to experience sharp increases in prepayment. Compounded by lower discounted rates, this causes substantial price appreciation for the PO. For the IO, however, the higher prepayments outweigh the lower discount rates and the net result is a price decline.

• If the rates drop by several hundred basis points, the collateral becomes a high-premium coupon and prepayments plateau. The rates of price appreciation of the PO and price deprecation of the IO both decrease. Eventually the IO’s price starts to increase, as the effect of lower discount rates start to outweigh the effect of marginal increases in prepayments.

• If rates rise, the slower prepayments and higher discount rates combine to cause a steep drop in the price of the PO. The IO is aided initially by the slower prepayments, giving the IO negative duration, but eventually prepayments plateau on the slower side of the prepayment S curve and the IO’s price begins to decrease.

Effective Duration and Convexity

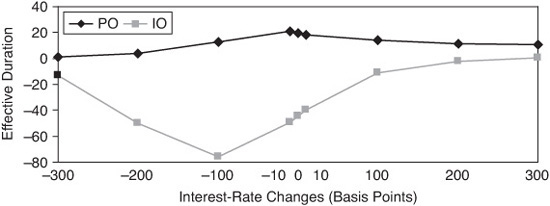

Exhibit 30–7 indicates that for current or low-premium collateral, POs tend to have large, positive effective durations, whereas IOs have large, negative effective durations. The effective durations in Exhibit 30–7 reflect the price paths in Exhibit 30–6:

EXHIBIT 30–7

IO and PO effective Durations for Current or Low Coupon Collateral

• For the PO, as rates decline the effective duration initially increases, reflecting its rapid price appreciation as prepayments surge. Note that this is in complete contrast to traditional measures such as Macaulay or modified duration, which, reflecting the shortening of the PO, would actually decrease. As rates continue to drop, the PO’s effective duration levels off and then decreases, reflecting both a leveling off of prepayments and the fact that, to calculate the effective duration, we are dividing by an increasing price. If rates increase, the PO’s duration decreases but remains positive.

• For the IO, the effective duration is initially negative and decreases rapidly as rates drop, before eventually increasing and becoming positive after prepayments plateau. If rates increase, the duration increases and eventually becomes positive.

Convexity measures the rate of change of duration and is useful in indicating whether the trend in price change is likely to accelerate or decelerate. It is calculated by comparing the price change if interest rates decrease with the price change if rates increase. Exhibit 30–8 shows the convexities obtained using the projected prices in Exhibit 30–6.

EXHIBIT 30–8

IO and PO Convexities

Comparing Exhibits 30–6 and 30–7 shows that the convexity indicates how the duration is changing. When the duration is increasing (as in the case of the PO when rates begin to decline from the initial value), the convexity is positive, and when the duration is decreasing, the convexity is negative. For example, the IO’s convexity is initially negative but begins to increase after rates fall by more than 100 basis points; although the duration is still negative at 200 basis points, the positive convexity indicates that the duration is increasing. The peak in the convexity of the IO at a change of 200 basis points indicates that the rate of increase in its duration is greatest at this point, as shown in Exhibit 30–7.

In summary, the prepayment S curve implies that for SMBS collateralized by

• Current or discount pass-throughs: The PO has substantial upside potential and little downside risk, whereas the converse is true for IOs.

• Low premiums: There is a somewhat comparable upside potential and downside risk.

• High premiums (including the majority of SMBS issued to date): The PO has little upside potential and significant downside risk, whereas the reverse is true for IOs.

Pricing of SMBS and Option-Adjusted Spreads

The strong dependence of SMBS cash flows on future prepayment rates, combined with the typically asymmetric response of prepayments to interest rate changes, make traditional measures of return such as yield to maturity of limited usefulness in analyzing or pricing SMBS. The most common method of pricing SMBS is with option-adjusted spreads (OAS). OAS analysis uses probabilistic methods to evaluate the security over the full-term range of interest rate paths that may occur over its term. The impact of prepayment variations on the security’s cash flows is factored into the analysis. The OAS is the option-free spread over the benchmark curve (Treasury or swap curve) provided by the security. It gives a long-term average value of the security, assuming a market-neutral viewpoint on interest rates.

Exhibit 30–9 shows the use of OAS analysis for a current coupon FNMA Trust and a premium FNMA Trust and the underlining pass-through security’s collateral. In each case, the price is chosen to give a Libor OAS (LOAS) of 30 basis points. Also shown are the yields-to-maturity and WAL (weighted average life).

EXHIBIT 30–9

OAS Analysis for Current Coupon and Premium FNMA Trusts

The OAS at a 0% volatility (the Z-Spread) when mortgage rates stay at current levels, is typically close to the standard benchmark curve spread in a flat yield-curve environment. The difference between the Z-Spread and LOAS, which we label the option cost, is a measure of the impact of prepayment variations on a security for the given level of interest rate volatility. The option cost, to a large extent, does not depend on the pricing level or the absolute level of prepayment projections (although it does depend on the slope, or response, of prepayment projections to interest rate changes). Hence, the option cost is a measure of the intrinsic effect of likely interest rate changes on an SMBS.

Before discussing the option cost in Exhibit 30–9, note that, in general, interest rate and prepayment variations have two effects on an MBS:

1. For any callable security, being called in a low interest rate environment typically has an adverse effect, since a dollar of principal of the security in general would be worth more than the price at which it is being returned. (An exception is a mortgage prepayment resulting from housing turnover, when the call could be uneconomic from the call holder’s point of view.) To put it another way, the principal that is being returned typically has to be reinvested at yields lower than that provided by the existing security.

2. For MBS priced at a discount or a premium, changes in prepayments result in the discount or premium being received sooner or later than anticipated. This may mitigate or reinforce the call effect discussed in (1).

In general, the first effect is much more important than the second; however, for certain deep-discount securities, such as POs, the second effect may at times outweigh the first. The net result of the two effects depends on the position of the collateral on the prepayment curve shown in Exhibit 30–5.

• The current coupon FNMA Trust, shown in Exhibit 30–9, illustrates the characteristics typical of SMBS collateralized by current or discount coupons. For discount or current-coupon collateral, prepayments are unlikely to fall significantly but could increase dramatically if there is a substantial decrease in interest rates. This asymmetry means that the PO is, on average, likely to gain significantly from variations in prepayment speeds. The option cost for the PO is usually negative; that is, the PO gains from interest rate volatility indicating that the benefits of faster return of principal outweigh the generic negative effects of being called in low interest rate environments. On the other hand, the underlying collateral tends to have a positive (but usually small in the case of discount collateral) option cost; the negative effect of being called when rates are low outweigh the benefits of faster return of principal. Finally, the IO typically has a large positive option cost; the asymmetric nature of likely prepayment changes, discussed in the preceding, means that the IO gains little if interest rates increase (since prepayments will not decrease significantly), whereas a substantial decline in rates is likely to lead to a surge in prepayments and a drop in interest cash flows.

• The premium FNMA Trust is representative of outstanding SMBS with premium collateral. For premium collateral, there is, generally speaking, potential for both increases and decreases in prepayments, and the net effect of prepayment variations will depend on the particular coupon and prevailing mortgage rates. Seasoned premiums, for example, will not have potential for substantial increases in speeds and hence, the premium Trust PO normally has a less negative option cost. The collateral has a positive option cost for the same reasons.

The importance of likely variations in prepayments makes the standard yield to maturity of very little relevance in pricing SMBS and therefore, they tend to be priced (as in Exhibit 30–9) on an OAS basis.

KEY POINTS

• Stripped mortgage-backed securities are created by redistributing all or portions of the interest and/or principal cash flows from a pool of mortgage loans to two or more SMBS classes.

• SMBS enable investors to capture the performance characteristics of the principal or interest components of the cash flows of mortgage pass-through securities. These individual components display contrasting responses to changes in interest rates and prepayment rates. PO SMBS are bullish instruments, outperforming mortgage pass-throughs in declining interest rate environments. IO SMBS are bearish investments that can be used as a hedge against rising interest rates.

• The particular characteristics of SMBS allow users and investors to execute their selected investment or hedging strategies.

• There are various types of SMBS securities, those non-Trust IO/PO securities (such as CMO strip securities) may exhibit slightly distinct behaviors dependent on the specific deal structure.

• Traditional measures of return such as yield to maturity are of limited usefulness in analyzing or pricing SMBS because of the strong dependence of SMBS cash flows on future prepayment rates together with the typically asymmetric response of prepayments to interest rate changes OAS analysis, a probabilistic method to evaluate SMBS over the full-term range of interest rate paths that may occur over its term, is commonly used.