CHAPTER

THIRTY-TWO

COMMERCIAL MORTGAGEBACKED SECURITIES

Managing Director

BlackRock

MARK D. PALTROWITZ

Managing Director

BlackRock

Commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) are structured products that provide debt financing to the commercial mortgage market. CMBS are a component of commercial real estate finance (commercial banks, insurance companies, and pension funds also make direct loans to owners of commercial real estate).

As with residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) products, CMBS represent economic interests in pools of mortgage loans. The structure used to create CMBS transfers the credit risk of the underlying commercial real estate loans to the owners of CMBS. Certificate subordination increasingly mitigates the commercial mortgage loan credit risk for certificate holders. CMBS certificate structures apply losses to the most junior outstanding certificates and, depending on the levels of subordination, offer substantial credit risk protection to the holders of the most senior certificates.

CMBS investors should understand the fundamentals of commercial real estate valuations and commercial real estate lending standards to properly analyze the credit risk embedded in CMBS investments. The loans underlying CMBS transactions are typically much larger than loans found in other securitized products. The largest 15 loans in a CMBS transaction can comprise 30% to 50% of a collateral pool. This loan concentration makes asset-level reviews much more important than other securitized products in which the law of large numbers allows effective statistical sampling. Key differences between CMBS and nonagency RMBS are enumerated in Exhibit 32–1.

EXHIBIT 32–1

Comparison of Key Attributes of CMBS Transactions and Nonagency RMBS Transactions

CMBS issuers have developed several types of transactions. Conduit transactions are securitizations of fixed-rate commercial mortgage loans in which no loan comprises more than 5% of a transaction and the largest 10 loans comprise less than 30% of the transaction. Fusion transactions are typically fixed-rate securitizations in which the 10 largest loans comprise more than 30% of the transaction. Issuers created single-sponsor transactions for sizeable debt offerings for large owners of commercial real estate. CMBS issuers have created floating-rate transactions typically comprised of large loans on transitional properties (i.e., under construction/renovation, undergoing a repositioning). These loans were usually for one or two years with several one-year extensions. Finally, CMBS issuers will bring “single sponsor” transactions to market when large institutional borrowers seek mortgage loans in amounts that justify a separate CMBS transaction.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Nishith Ajitsaria and Kunal Khara, CFA in writing this chapter.

The majority of CMBS transactions are considered Fusion transactions. Given the lumpy nature of the collateral concentrations in Fusion transactions, CMBS investors (regardless of credit support) typically perform due diligence on the largest loans to understand whether the mortgage loan originator used a prudent valuation and sized the loan appropriately.

THE COLLATERAL POOL

Because most CMBS transactions have large loans that comprise significant portions of the overall trust, investors typically perform a review of the underlying mortgage loans and mortgaged properties to understand the idiosyncratic credit risks of the investment.

Summary of Valuation Techniques for Underlying Mortgage Properties

Typically, office, retail, industrial, hospitality, and multifamily properties serve as collateral for the underlying mortgage loans. Office, retail, industrial, and hospitality properties constitute “commercial” properties, whereas multifamily properties typically have more than four units available for lease. Commercial real estate values are typically computed by using the direct capitalization method, a discounted cash-flow analysis, the comparables method, or the replacement cost method. The direct capitalization method utilizes a capitalization rate (cap rate), which is the unleveraged yield associated with the current income from a commercial property. The direct capitalization method determines property value by using the following formula:

Property Value = Net Operating Income/Cap Rate

Cap rates are based on many factors and include an interest rate component. Multifamily properties have typically garnered the lowest average cap rates due to availability of debt financing from the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) as well as the ability to reset rents on a frequent basis due to short-lease terms. Hospitality properties generally average the highest cap rates due to the volatility of the net operating income associated with the hospitality and travel/leisure industries. Investors value office, retail, and industrial properties with average cap rates between the multifamily and hospitality benchmarks. The direct capitalization method is useful to CMBS investors because the data inputs are typically available from dealers, such that the analysis is based on a standardized data-set.

The discounted cash-flow analysis (DCF analysis) is a more precise method of commercial real estate valuation that discounts the property’s net operating income through time using the weighted average cost of capital as a discount rate. Commercial real estate equity investors utilize a DCF analysis when purchasing commercial real estate properties; however, CMBS investors typically do not have the required inputs (i.e., cash-flow forecast) to use this valuation technique.

The comparables method attempts to determine commercial real estate values by determining a property’s value based on the actual sales of similar properties in the same area. This approach is effective at finding a market value if similar properties traded in the recent past. When marketing CMBS investments, dealers often verbally disclose comparables for the properties securing the largest mortgage loans within a transaction. Property values are distilled to a value/square foot (SF) or unit. As an example, Midtown Manhattan Class A (high-quality) office buildings can trade at $800 to $1200/SF, whereas suburban office buildings in secondary markets can trade at $100/SF. Although dealers make comparable information available during the offering of a CMBS transaction, updated information is not made available through transaction reporting.

The replacement cost approach values real estate by computing the value of the underlying land and the cost associated with constructing the property’s improvements less depreciation. This method is not used extensively in commercial real estate valuation as it does not take into account the property’s income stream. The appraiser is also required to determine the value of land using the comparables method—given that land sales in highly developed areas are rare, valuations based on this approach would require significant assumptions.

The classic guideline for commercial real estate valuation has not changed in the modern era: Location is essential to determining real estate values. A CMBS investor should appreciate and consider the bespoke nature of commercial real estate properties and their values to properly model the commercial real estate debt exposures in a CMBS transaction.

Commercial Mortgage Lending Standards

As with most hard assets of reasonable credit quality, owners of commercial real estate can improve their overall yields by utilizing leverage. Mortgage loans are sized based on the ratio of the debt to the value of the property (the loan-to-value ratio or LTV). Most owners of commercial real estate will borrower 50% to 80% of the value (or acquisition cost) of the property. Typically most CMBS originators will make loans up to 75% to 80% LTV. In 2006 and 2007, CMBS originators offered loan products that provided borrowers up to >95% LTV. During the 2008 financial crisis, most commercial real estate debt offerings (including CMBS) disappeared along with market liquidity. If debt was available, the terms were generally economically punitive (i.e., high coupons and maximum loan sizes up to 50% LTV based on depressed property values).

Mortgage loans are also sized based on the ratio of the net operating income of the underlying collateral to the debt service of the mortgage loan. This ratio is the debt service coverage ratio (DSCR). CMBS originators usually require a minimum DSCR of 1.2×; however, certain property-level characteristics could enable a CMBS originator to make a loan at lower DSCR thresholds (e.g., collateral is a long-term ground lease or tenants with lease terms greater than 15 years).

Loan Structures and Features

CMBS dealers will disclose many loan features in the offering documents of a CMBS transaction. Commercial mortgage loans are generally originated with structural features to isolate the underlying collateral for the benefit of the trust. Most borrowers are single-purpose entities (corporations or limited liability companies) that are created for the sole purpose of owning the commercial real estate that is security for the mortgage loan. For larger loans, the single purpose entity includes organizational features that make it difficult for the borrower to declare bankruptcy. These legal protections are necessary for loans underlying CMBS transactions since most loans are nonrecourse, meaning the lender’s only recourse in the event of a loan default is seizing the underlying collateral.

CMBS originators require additional loan features to protect the trust in the event the borrower fails to prudently operate the mortgaged property. CMBS originators typically require borrowers to establish reserve accounts with the loan servicer for various property expenses. For example, CMBS originators may require the borrower to remit the prorated portion of the annual property tax and property insurance payments as part of its monthly payment. CMBS originators could also require borrowers to make monthly payments for replacement reserves, tenant improvement, and leasing commissions. Depending on the mortgaged property and its condition, CMBS originators could also require debt service reserves, ground lease reserves, and other reserves to mitigate specific property conditions.

From 2005 to 2007, many borrowers benefited from “holdbacks,” which are additional loan proceeds that were held in reserve by the servicer. Holdbacks could be released to the borrower upon the achievement of certain property benchmarks (leasing goals, net operating income (NOI) goals, occupancy goals, and the like). Many of these metrics were based on aggressive property performance expectations that many mortgaged properties failed to achieve due to the financial crisis. In the event the holdback release criteria were not met, many holdbacks would serve as additional loan collateral. In some cases, unreleased holdbacks could be used to pay down the loan principal balance and would cause a prepayment to the certificate holders.

CMBS originators typically require lockbox structures. Lockboxes are deposit accounts held by the servicer. If the CMBS originator required a hard lockbox, immediately following the closing of the loan, the borrower would be required to notify all tenants to forward their rental payments and reimbursements to the servicer for deposit in the lockbox and the borrower would have access to the funds pursuant to the terms of the loan documents. Originators impose various conditions on the release of funds from lockboxes. In many instances, the servicer will fund escrows and debt service on a monthly basis and release the remaining funds to the borrower. As the CMBS market matured, originators would permit soft lockboxes that allowed the servicer to sweep all amounts in the lockbox to a borrower-controlled account on a daily basis. Upon an event of default, the stringent cash management provisions would be imposed and the borrower would no longer have access to funds from the lockbox.

CMBS loans typically restrict prepayment during the loan term. CMBS originators would typically “lock out” all loans from prepayment during the first two to four years of the loan term. After this initial lockout period, borrowers could defease the underlying mortgaged property by substituting U.S. government securities as collateral for the loan. The substituted securities would be redeemed to make the interest and principal payments of the underlying loan on schedule. The defeasance feature is acceptable to CMBS investors because it preserves the contracted loan cash flows. In some cases, in lieu of defeasance, CMBS originators would allow borrowers to prepay their mortgage loans with the payment of a prepayment penalty or yield maintenance charge. These prepayment penalties would partially compensate certificate holders for an early prepayment of a mortgage loan since their overall yield could be negatively affected by the prepayment.

CMBS originators will sometimes cross-collateralize several mortgage loans. This feature is utilized when a borrower finances several properties using separate mortgage loans (rather than collateralizing a single mortgage loan with multiple properties). Cross default occurs when the originator requires the borrower to agree that any default under the identified set of mortgage loans will cause a default under all the mortgage loans. Cross-collateralization is the corollary feature that allows the CMBS originator to use the collateral securing all mortgage loans to offset the loss on any single mortgage loan.

Diversification of CMBS Loan Pools

In order to understand credit risk, CMBS investors focus on large mortgage loan exposures and collateral concentration. The Wachovia Bank Commercial Mortgage Trust, Series 2007-C32 (WBCMT 2007-C32) illustrates many of the loan features, pool concentrations, and certificate features described in this chapter. Exhibit 32–2 describes the top 15 loans in the WBCMT 2007-C32 transaction.

EXHIBIT 32–2

Top 10 Loans in WBCMT 2007-C32

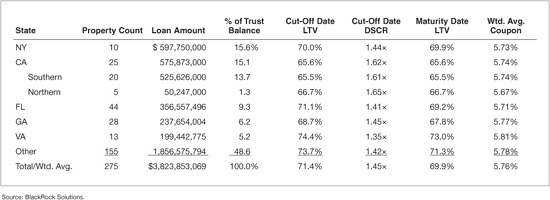

CMBS transactions usually contain mortgage loans from all US regions. Exhibit 32–3 illustrates the geographic concentration of WBCMT 2007-C32.

EXHIBIT 32–3

Top Five Geographic Concentration of WBCMT 2007-C32

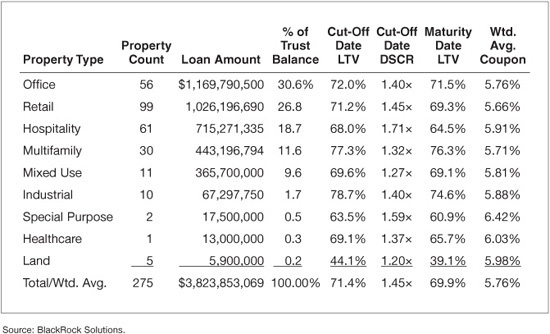

CMBS transactions should also contain adequate property type diversification. Concentration in a particular property type may make a CMBS transaction susceptible to specific downturns in a particular industry or segment of the economy. Exhibit 32–4 illustrates the property type concentrations in WBCMT 2007-C32.

EXHIBIT 32–4

Property Type Concentration of WBCMT 2007-C32

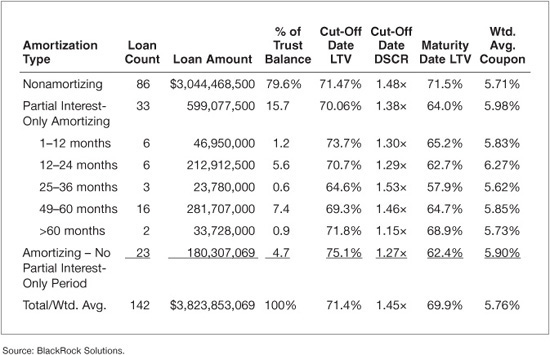

The mortgage loans sold into a CMBS transaction should also provide adequate protection by including amortization. CMBS originators required amortization in the earliest vintages of CMBS but shifted to a preference of interest-only or partial interest only loans in later vintages of CMBS. Exhibit 32–5 illustrates the interest-only concentrations in WBCMT 2007-C32.

EXHIBIT 32–5

Stratification of Amortization Type of WBCMT 2007-C32

CMBS transactions may also include multiple loans to the same ownership group (Loan Sponsor) that are not cross collateralized. CMBS dealers typically make this information available during the offering process. CMBS investors should monitor the borrower concentrations in conduit or fusion transactions to ensure adequate diversity of borrower risk. Exhibit 32–6 provides a stratification of Loan Sponsors in the WBCMT 2007-C32 transaction.

EXHIBIT 32–6

Loan Sponsor Concentrations in WBCMT 2007-C32 in Excess of 5%

To mitigate concentration risk from the largest loans and keep the exposure below certain size thresholds that would require additional disclosures, CMBS issuers may split mortgage loans into multiple pieces. Structures could range from A/B note structures, in which the B note provides subordination to the senior A note. Originators also split loans into “pari passu” structures in which the individual notes receive a pro-rata portion of principal and interest (and losses in the event of a note loss).

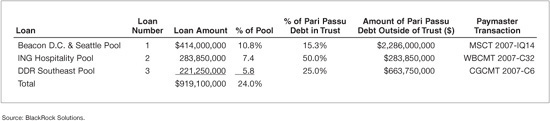

If an originator creates a pari passu loan structure, the servicing of the loan would be assigned to the servicer of the first securitization that owns the first securitized note from the pari passu loan. This servicer (the Paymaster) is responsible for collecting the loan payments and administering the loan for all the various notes created by the originator. Exhibit 32–7 describes the pari passu loans in WBCMT 2007-C32.

EXHIBIT 32–7

Pari Passu Loans in WBCMT 2007-C32

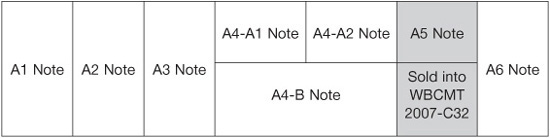

The Beacon D.C. & Seattle Portfolio loan is one of the most complex mortgage loans sold in a CMBS transaction. The $2.7 billion loan was originally split into 6 pari passu notes. After the first notes were securitized, the CMBS originator split one of the pari passu notes (the A4 Note) into three notes. CMBS originators adjust the size of the pari passu notes based on the size of the overall CMBS transaction that acquires the pari passu note. All of the A pari passu notes comprising the Beacon D.C & Seattle Portfolio loan were securitized in various CMBS fusion transactions. Exhibit 32–8 illustrates the loan structure.

EXHIBIT 32–8

Loan Structure of the Beacon D.C. & Seattle Portfolio

By performing due diligence on the largest 10 loans in a CMBS transaction, CMBS investors can understand the credit risk profiles of approximately 30% to 50% of the collateral.

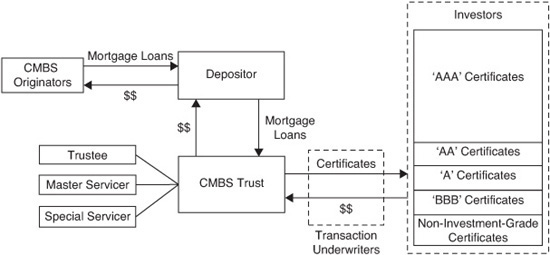

CMBS TRUST STRUCTURE

CMBS transactions begin with the origination of commercial mortgage loans by loan originators. Various insurance companies, specialty finance companies, conduits, and banks have served as mortgage loan originators for CMBS transactions. Mortgage loans are sold by the originators to a depositor entity to aid the legal isolation of the mortgage loans. The depositor typically forms a common law trust via a Pooling and Servicing Agreement and transfers the mortgage loans to the trust. The trust issues certificates to investors in an aggregate amount that equals the cut-off balance of the mortgage loans. There is typically no over- or under-collateralization of CMBS trusts.

The rating agencies are engaged early in the transaction structuring process to review the proposed loan pool and provide preliminary certificate subordination levels for a CMBS transaction. Mortgage loan originators provide each rating agency with data and loan files to assist the rating agencies with performing their loan due diligence and site visits for properties securing mortgage loans. Rating agencies perform due diligence on the underlying loans and properties, including site visits, to determine the subordination levels required to achieve specific ratings. The issuer and transaction underwriters prepare various documentation for the transaction including the prospectus, pooling and servicing agreement (PSA), and Annex A, which contains detailed information about the underlying loans in the collateral pool. The transaction underwriters market the CMBS certificates to potential investors. The transaction underwriters acquire the certificates from the trust on the transaction settlement date and transfer the certificates to the investors. Exhibit 32–9 illustrates the relationships between the standard transaction participants.

EXHIBIT 32–9

Diagram of Mortgage Loan Transfer, Certificate Issuance and Transaction Participants

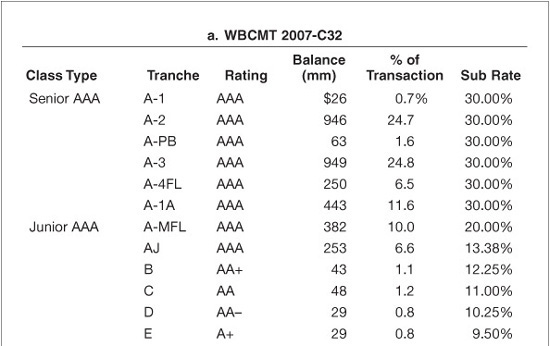

Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, CMBS transactions consisted of tranches at every rating notch resulting in thin classes susceptible to being completely written down in the event a large loan experiences significant loss. Subsequent to the 2008 financial crisis, CMBS issuers have simplified capital structures by creating thicker classes that are better able to withstand the default of a single loan. Exhibit 32–10 illustrates typical CMBS certificate structures before and after the 2008 financial crisis.

EXHIBIT 32–10

Illustration of CMBS Certificate Subordination Levels and Ratings before and after the 2008 Financial Crisis

TRANSACTION PARTICIPANTS

Post-securitization, several parties are involved in the administration and management of a CMBS trust. The trustee is the administrator of the assets and liabilities of the CMBS trust and fulfills a variety of responsibilities. The trustee calculates and distributes principal and interest payments to CMBS certificate holders, prepares and discloses periodic remittance data, and maintains the trust’s books and records. In certain cases, the trustee also provides support to the master servicer if the latter is unable to fulfill its responsibilities. The trustee receives a fee from the monthly interest income generated by the collateral for performing its duties. The trustee fee is senior to certificate holder interest payments. The trustee can also earn additional income by reinvesting cash flows received from the servicer that will be transferred to certificate holders at a later date.

The master servicer collects loan payments for distribution to the trustee, in addition to performing basic servicing duties such as management of escrows, reserves, and lockboxes. The master servicer collects and provides periodic loan performance data and property financials to the trustee and rating agencies. When a loan becomes delinquent or distressed, the master servicer transfers its servicing duties to a special servicer that focuses on workout and loss mitigation activities. The master servicer continues to advance principal and interest on the delinquent loan to the trust as long as the advances are deemed to be recoverable upon loan workout. The master servicer also receives a fee that is generally a few basis points of the outstanding mortgage balance. The master servicer’s fee, similar to the trustee’s fee, is also senior to certificate holder interest payments. The master servicer can also earn additional income by reinvesting underlying mortgage cash flows for a period of time prior to transferring to the trustee.

The special servicer handles distressed loans, which may be in delinquency, bankruptcy, foreclosure, etc. The determination of a distressed loan is typcially made by the master servicer, who then transfers the loan to the special servicer for timely resolution and implementation of workout procedures. The special servicer’s responsibility to the CMBS trust is to maximize recovery value of the distressed loan. The special servicer receives a monthly fee during the loan workout period based on the outstanding loan balance. The special servicer also receives compensation for a loan resolution, depending on whether a loan is liquidated or modified. Similar to the trustee and master servicer fees, the payments due to the special servicer are paid prior to allocating cash-flows to the certificate holders.

CMBS transactions typically designate the most subordinate tranche as the controlling certificate holder. Since the controlling certificate holder is in the first loss position if the CMBS transaction sustains losses from a defaulted loan, the controlling certificate holder (via the controlling class representative) is empowered to make certain decisions. The controlling class representative is typically granted the power to (1) replace the special servicer and (2) approve the disposition plan for loans in special servicing. These control rights migrate to the class immediately senior to the current controlling certificate holder if the controlling certificate holder sustains losses in excess of 75% of its original certificate balance. Prior to 2000 and after 2008, CMBS transactions typically require the control rights to pass to the next most senior certificate holder when principal losses and ARAs (defined below) exceed 75% of the controlling certificate holders original certificate balance. In contrast, CMBS transactions issued from 2000 through 2008 allowed the controlling certificate holder to remain in place even when principal write downs in excess of 75% of the controlling certificate holders original certificate balance were imminent.

TRANSACTION FEATURES

CMBS issuers generally incorporate a standard set of transaction features regardless of vintage. With few exceptions, CMBS transaction features have remained generally static since the 1990s with issuers incorporating small changes to meet investor demands.

Subordination

CMBS certificates are created along time and credit dimensions to create a “capital structure” with varying cash flow and risk profiles that cater to different investors. For example, senior certificates typically have priority to principal payments, and therefore, are the shortest certificates in a transaction. Junior certificates are subordinate to senior tranches with respect to principal cash flows and are also first in line to absorb collateral losses. The subordination rate, which is a measure of credit support for a certificate, is defined as the percentage of the collateral balance that must experience a complete principal write-down before the certificate in question is exposed to principal loss. Subordination rates are highest for the senior most certificates in the transaction and decrease down the capital structure.

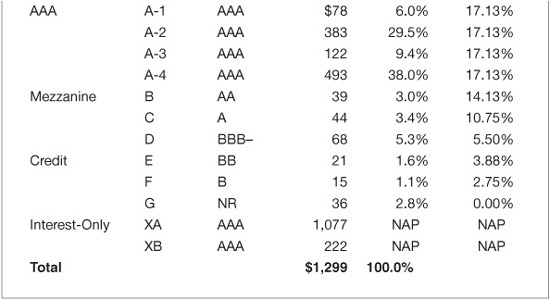

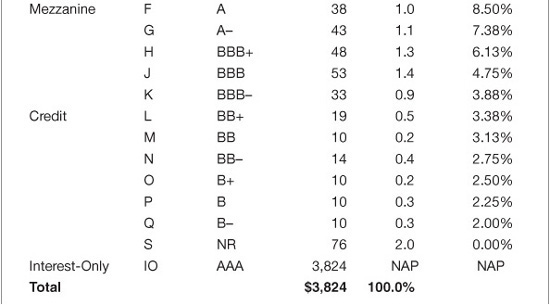

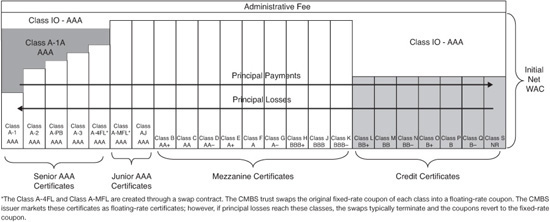

Conduit transactions have three distinct categories of principal-pay certificates—AAA classes, mezzanine classes, and junior credit classes—with one or more interest-only (IO) certificates. The AAA classes are generally further divided into three different subordination levels starting with super-dupers (senior-most tranches in the transaction—classes A1 through A4 in Exhibit 32–10) at the top of the capital structure having attained the highest subordination rates (usually 30%), followed by mezzanine AAA (the AM class), and junior AAA (the AJ class) certificates. CMBS issuers created the super-duper and mezzanine AAA structures based on investor feedback. CMBS issuers determined the junior AAA subordination levels based on rating agency feedback.

The super-duper AAA certificates constitute approximately 70% of the transaction principal balance and are the senior most certificates in the transaction. A typical conduit transaction has six duper classes—A1, A2, A3, A4, APB, and A1A—each with a different cash-flow profile. The A1 certificate, which is the first-pay AAA, is the shortest certificate in the transaction with a WAL of approximately two years. The A1 also amortizes gradually over time, unlike the A2 and A3 certificates, which have bullet-like principal cash-flow profiles because they are usually tied to five- or seven-year balloon loans. In order to maintain the bullet cash-flow profile of the medium-term AAAs, the APB tranche absorbs amortizing principal cash flow between the maturities of the A2 and A3 classes. The A4 certificate is typically the largest of the AAA classes and also has the longest WAL. The A4 class is often referred to as the benchmark certificate of the transaction. Similar to A2 and A3 classes, the A4 certificate also has a bullet-like principal cash-flow profile tied to 10-year balloon mortgages. Lastly, the A1A class is created only if multifamily and manufactured housing loans exist in the CMBS transaction and is structured specifically for the GSEs to receive the cash flows from selected mortgage loans that meet the GSE’s underwriting and/or affordable housing standards.

The mezzanine AAAs (AM classes) usually carry 20% subordination while junior AAAs (AJ classes) carry 10% to 15% subordination level—actual subordination levels vary by transaction and are based on the feedback from rating agencies. AM and AJ certificates are also tied to balloon loans with bullet-like principal cash-flow profiles. Mezzanine classes are typically rated between AAA and BBB– and constitute a small portion of the original transaction balance. Mezzanine certificates are generally tied to 10-year balloon payments. CMBS transactions can also include tranches rated below BBB—or unrated first-loss classes known as B-pieces. These tranches are tied to the longest maturity loans in the collateral pool. The B-piece is generally the controlling class and retains certain voting rights that allow them to replace the special servicer.

Pass-Through Rates

Traditional conduit transactions are structured such that the net weighted average coupon of the collateral (the assets) exceeds the weighted average coupon of the certificates (the liabilities). The net weighted average coupon of the collateral equals the weighted average coupon of the collateral less the fees payable to the trustee and master servicer. This structure results in excess interest cash flow which is directed to the IO tranches. IOs by definition do not receive any principal.

Conduit CMBS certificates can have three types of coupon structures: fixed-rate, WAC (weighted average coupon), and WAC-capped. Most CMBS tranches pay a fixed-rate coupon. WAC certificates pay the weighted average net coupon of the collateral, which can vary over time as the composition of the collateral pool changes. WAC-capped certificates pay the minimum of a fixed-rate and the WAC rate and are generally lower in the capital structure.

Priority of Payments

In general, given the relative simplicity of CMBS capital structures, the allocation of cash flows and losses across the capital stack—known as the “waterfall structure”—is fairly straightforward. The APB and A1A tranches add a layer of complexity, which is described in detail below.

Principal payments are allocated sequentially from the top of the capital structure to the bottom. Principal cash flows are generated from loan maturities, scheduled amortizations, prepayments, and default recoveries. The sequential payment structure implies that in general a certificate will receive principal payments only if the tranches senior to it in the capital structure have completely paid off.

The A1A tranche receives its cash flow exclusively from designated multifamily and manufactured housing loans in the collateral pool. The rest of the tranches are allocated cash flows from the remaining collateral pool. The APB tranche first receives principal in accordance with its amortization schedule and any excess is diverted to the A1, A2, A3, and A4 classes in sequential order. The A1 tranche (which is the first-pay certificate) receives principal payments only if the APB tranche has received its allocated principal to date. Following the sequential structure, the A2 class does not receive any principal until the A1 class has been fully paid off, and the A3 class does not receive any principal until the A2 class has been paid off. Once the A3 class has been paid off, all principal from the non-multifamily pool is distributed to the APB class. Finally, once the A1, A2, A3, and APB classes are fully paid off, principal cash flow is allocated in sequential manner to the other classes.

While principal is allocated in “top-down” fashion, losses are allocated “bottom-up” in reverse-sequential order. Given that the credit enhancement in a CMBS transaction is in the form of subordination, a particular tranche will not experience losses until the certificates underneath it in the capital structure are completely written down. It is important to note that all the super-duper certificates in a transaction share the same level of subordination. As a result, although principal cash flows are allocated sequentially to the super-duper certificates, losses are allocated pro-rata across the super-duper certificates after the more junior tranches experience complete principal write downs. Interest payments are allocated pro-rata to the super-duper certificates and to the IO tranche and then sequentially to the rest of the certificates. Interest cash flows are a function of current debt service payments plus any late interest payments from prior periods, received in the current period.

Exhibit 32–11 illustrates the certificate subordination and priority of payments for the WBCMT 2007-C32 transaction.

EXHIBIT 32–11

WBCMT 2007-C32 Certificate Structure

Interest-Only Certificates

Most CMBS fusion transactions also have an IO tranche. As mentioned, the weighted average coupon that is paid to all the non-IO tranches is generally less than the total interest from the collateral pool. This excess interest is allocated to the IO tranche, once all the non-IO tranches in the trust have received their allocation of the interest payments. The notional balance of the IO tranche may be based on the aggregate balance of the AAA tranches alone or on the entire transaction, depending on the level of the coupon being stripped off of various tranches.

If the difference between the collateral and certificate coupons is substantial, transactions may contain a planned amortization class (PAC) IO structure, where multiple classes of IOs exist, with one class of IO certificates treated as support bonds to absorb the impact of prepayments so that the PAC IO investor receives stable cash flow and low yield variability.

Payment Advancing and Appraisal Reductions

When a loan becomes delinquent, the master servicer is generally obligated to advance principal and interest to the trust to minimize the variability in monthly cash flows to the certificate holders. However, the amount the servicer advances is based on whether it deems the advanced amounts to be recoverable upon liquidation. In order to determine the advanced amount, the servicer hires an appraiser who appraises the property. A haircut (typically 10%) is applied to the appraisal amount and compared to the outstanding loan balance at the time of delinquency. The servicer then advances payments based on the lower of the outstanding loan balance and the adjusted appraised value. This difference is called an Appraisal Reduction Amount (ARA). If the delinquency level in a trust is fairly high or if appraised values are substantially lower than the outstanding loan balances, there could be a situation in which interest shortfalls could result to the trust since the servicer’s advances are not enough to cover interest payable to all certificate holders. Once the loan is liquidated, proceeds from the liquidation will go first to the servicer to reimburse servicing advances.

Clean-up Call Provisions

Each CMBS transaction includes a clean-up call provision that enables the outstanding certificate holders to purchase the remaining mortgage loans in a trust. The clean-up call is usually limited to when the remaining balance of mortgage loans represents approximately 1% and 3% of the original balance of the trust. The purchase price is typically the outstanding balance of the mortgage loans plus accrued interest. The clean-up call is utilized to wind-down CMBS transactions when the balance remaining in the transaction is too small to justify the ongoing administration costs.

MARKET DEVELOPMENT

The CMBS market developed in the early 1990s with the need to dispose of commercial real estate loans owned by the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC) as a consequence of the savings and loan crisis. The RTC packaged loans from failed institutions into CMBS transactions using a Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduit (REMIC) structure under the tax code. This provision was passed as part of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 and allows tranches of securities that would otherwise be treated as equity interests to be treated as debt instruments. The CMBS market grew quickly in the 1990s, culminating in issuance of $74 billion in 1998. The Russian debt crisis and related contagions created substantial turmoil in the debt markets in August 1998, causing a temporary slowdown in CMBS issuance. Transaction volume surpassed 1998 levels in 2003 and CMBS issuance underwent explosive growth through 2007 with $228 billion of issuance as demand for high-quality spread products remained elevated.

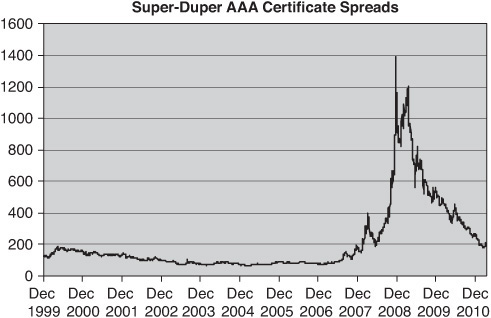

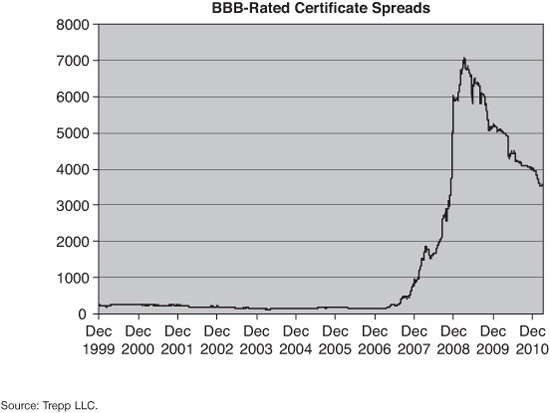

From 2001 through 2007, CMBS credit-spreads experienced a general tightening trend.1 At the height of the market in early 2007, CMBS spreads relative to Treasuries (T) had tightened to approximately T+0.60% for 10-year super-duper AAA certificates and T+1.20% for BBB-rated certificates. The 2007 subprime mortgage crisis impacted CMBS pricing and in August of 2007, spreads on 10-year super-duper AAA certificates had widened considerably (T+1.50%). Spreads on BBB-rated certificates in early 2007 were T+1.25% and subsequently widened to T+4.75% by the fall of 2007. With spreads widening and contagion from the subprime crisis spreading, issuers curtailed loan originations, in part due to their inability to hedge credit-spread risk in a spread-widening environment. Issuers delivered nine transactions in 1H-2008 with the CMBS market seizing up in July 2008. No privately sponsored CMBS issuance was brought to market until Q4-2009, when the only TARP-eligible securitization was sold to the market. In 2010, the market slowly experienced increased transaction volume with total annual private issuance of approximately $13 billion. See Exhibit 32–12 for CMBS spread history for certain classes.

EXHIBIT 32–12

History of CMBS AAA and BBB Spreads (in Basis Points) to 10-Year U.S. Treasuries

MODELING

Market participants consider two primary types of risks when analyzing CMBS—interest rate risk and credit risk. Interest rate risk is important given most certificates are fixed-rate and relatively long duration because the underlying loan maturities are in the 5- to 10-year range. Credit risk is relevant since any losses resulting from loan defaults are borne by the certificate holders.

The 0/0 Scenario

Prior to the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent downturn, commercial mortgage defaults had been low and had not impacted senior certificates. As a result, investors traditionally relied on what is referred to as a 0/0 framework, which means zero prepayments (as measured by the conditional prepayment rate, CPR) and zero default rates (as measured by the conditional default rate, CDR), to quote CMBS prices and yields. This implies that there are no prepayments, defaults, or losses on the collateral pool. This simplistic modeling framework is often augmented with additional loan default and extension scenarios as liquidations and extensions have become more common. Prepayment risk is generally not significant for commercial mortgages due to typical prepayment restrictions at the loan level.

Probabilistic Modeling

Probabilistic models attempt to draw statistical relationships between commercial loan performance and identified drivers of performance. For example, loan default and severity are generally built as a function of DSCR and LTV. All else equal, perceived credit risk is higher with higher LTV and lower DSCR. Investors attempt to project future loan performance by studying the empirical relationship between historical defaults/severities and the pool’s DSCR/LTV.

Deterministic Modeling

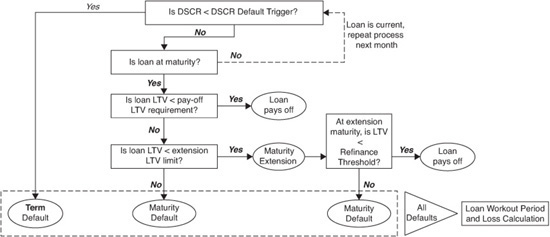

Since loan-level commercial mortgage performance datasets are not readily available, market participants more commonly rely on a deterministic modeling approach. Deterministic models employ a rules-based framework in which loan outcomes are determined by projected property performance and valuation after subjecting the underlying collateral to a series of tests and triggers. Loan performance and valuation are estimated using projected DSCR and LTV (similar to probabilistic models), which in turn are calculated from NOI and cap rate. The NOI and cap rate inputs into deterministic models can vary by property type and/or geography and are typically generated using macroeconomic models that incorporate real estate fundamentals. Each mortgage loan’s projected DSCR and LTV is compared through time to a set of trigger levels to discretely determine one of three possible loan outcomes: term default, timely pay-off, or maturity default/loan extension. The three loan outcomes are described in more detail below:

• Term Default: During the term of the mortgage loan, periodic tests are run to determine if the loan’s DSCR drops below a pre-defined DSCR default trigger. The loan is immediately defaulted and enters a workout period if the DSCR trigger fails. At the end of the workout period, the property’s terminal value is determined using NOI and cap rate, less a workout or disposition fee. If the final property value is less than the outstanding loan amount, the deficit is recorded as a loss. If the property’s NOI never drops below the DSCR trigger, no default is assumed during the loan’s term.

• Timely Pay-off: At the loan’s maturity date, property value is once again determined by applying a cap rate to projected NOI. The loan is assumed to pay-off on time if the property value is sufficiently above the outstanding loan amount (e.g., LTV < 80%).

• Maturity Defaults/Loan Extensions: If the loan does not pay-off as scheduled at maturity, it either enters into a one-time term extension or defaults. Deterministic models generally assume that the loan is extended as long as it is not underwater (LTV < 100%), whereas under-collateralized loans (LTV > 100%) are assumed to default at maturity. In the case of maturity default, the property value is calculated at the end of the workout period to determine the loss amount. If the loan is extended, the pay-off versus default calculation is repeated at the end of the extension period.

The DSCR and LTV thresholds are typically set based on a combination of observed historical performance, real estate market trends, and the participant’s experience and judgment. Exhibit 32–13 is a graphical representation of a sample deterministic framework.

EXHIBIT 32–13

Deterministic Model Logic Tree

KEY POINTS

• There are major structural and modeling differences between CMBS and other mortgage products.

• Most CMBS transactions are conduit or fusion transactions with diversified exposure by geography and property type: office, retail, industrial, hotel, and multifamily are the primary real estate asset types.

• CMBS typically have many structural features that protect senior investors from credit losses while allowing flexibility for the senior portion of the capital structure to target narrow maturity windows.

• Impacts of prepayments can be somewhat muted given the prepayment restrictions of most mortgage loans.

• Given the idiosyncratic nature of commercial real estate within CMBS transactions, bottom-up loan and property level analysis is necessary to understand the underlying credit and extension risks.