CHAPTER

THIRTY-FOUR

SECURITIES BACKED BY AUTO LOANS AND LEASES, EQUIPMENT LOANS AND LEASES, AND STUDENT LOANS

Director, Head of Consumer ABS Research

Wells Fargo Securities, LLC

The securitization of nonmortgage financial assets has been providing firms with direct access to the capital markets since 1985. It is generally accepted that the asset-backed securities (ABS) market first began with a computer lease transaction sponsored by Sperry Lease Finance Corporation. Shortly thereafter, auto loans were being financed using securitization technology. Many other types of consumer and commercial assets have been added to the mix, and the nonmortgage ABS market grew from these humble beginnings to about $800 billion outstanding by 2007. Since the financial crisis of 2008–2009, the ABS market shrunk from its peak, but it remains an important source of capital for the financial system. This chapter describes the securitization process and summarizes some of the key features of three of the larger asset classes in the ABS market: auto loans and leases, equipment loans and leases, and student loans. Securities backed by credit card receivables are covered in Chapter 33.

SECURITIZATION IN BRIEF

Securitization is a process in which financial assets are sold to a special purpose vehicle (SPV) from the originator of the assets. Assets securitized are primarily loans and leases, but many other types of receivables and financial obligations, such as accounts receivable or utility charges, have found their way into the ABS market. The use of an SPV in securitization is a critical step because the assets should be isolated from any potential bankruptcy of the originator. This bankruptcy remoteness allows the debt of the SPV to carry credit ratings that may be higher that those of the originator of the assets backing the securities sold to investors. The vast majority of ABS sold to investors, in fact, carry a AAA rating from one or more credit rating agencies. In the event of the insolvency or bankruptcy of the originator, the cash-flows from the assets should be able to stand on their own to service the debt and not be consolidated with the bankruptcy estate.

The SPV issues securities to investors that are backed by the cash-flows generated by the assets. The assets are typically a diversified pool with hundreds or thousands of obligors. However, in some cases, there may be certain concentrations, either geographic, obligor, or industry, that may need to be mitigated in the structure or with additional credit enhancement. Interest collections on the assets are used to pay interest to the bondholders, and principal collections are used to repay principal to bondholders. As noted, investors rely on the underlying pool of collateral for repayment and not on the creditworthiness of the originator, or seller of the assets.

This is not to say that the originator or servicer of the collateral pool does not matter. On the contrary, the lender’s ability to originate high-quality collateral and service the loans effectively is critical to the success of a securitization. Indeed, the rating agencies explicitly take account of those abilities when determining the amount of the credit enhancement (i.e., referred to as sizing) required to achieve the desired credit rating on the ABS. In most cases, the originator of the loans will also be the servicer.

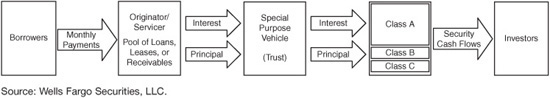

Exhibit 34–1 displays a generalized schematic of the securitization process. After the assets (loans, leases, receivables, or the like) are sold to the SPV, the transaction can be structured and the securities sold to investors. Most ABS transactions offer a senior class of securities (Class A) that are usually rated AAA by one or more credit rating agencies. Subordinated securities, usually rated in the investment grade categories (AA to BBB), may also be offered to investors or they may be retained by the issuer.

EXHIBIT 34–1

Securitization Flow Chart

The key to receiving credit ratings on ABS backed by a pool of unrated assets is the credit enhancement required. The amount of credit enhancement required will be related to the level of expected credit losses on the collateral pool. For example, a pool of auto loans to prime quality borrowers might be expected to generate credit losses of just 1% of the original balance of the loans. Alternatively, a pool of auto loans to subprime borrowers might be expected to generate losses of 10%. The ABS deal backed by the subprime loans would require substantially more credit enhancement to achieve the same rating than would the ABS deal backed by prime auto loans.

Credit Enhancement

The major types of credit enhancement for ABS transactions include internal sources and external sources. External sources are mainly bond insurance and corporate guarantees that link the rating of the ABS directly to the corporate credit rating of the guarantor. This method of credit enhancement came under severe stress during the financial crisis of 2008–2009, and has fallen out of favor to a large degree since then. Internal sources of credit enhancement include excess spread, cash reserve account, over-collateralization, and subordination. Some combination of them is found in almost every ABS deal.

Excess spread is the amount of interest collected above and beyond that needed to pay interest to bondholders and pay the ongoing expenses of the transaction. This is the first line of defense against losses in most ABS because it can absorb credit losses in each period. The excess interest usually goes back to the servicer if it is not used in a particular payment period, unless it is trapped in an account for the benefit of the bondholders.

A cash reserve account may be fully funded at the closing of the ABS transaction, or it may be added to or funded over time by retaining (i.e., trapping) the excess spread. The reserve account is available to provide the deal with additional liquidity in the event that interest or principal collections are less than expected. Cash reserve accounts may also allow funds to be distributed to the originator if credit performance meets certain objectives in terms of quantitative tests. Individual ABS transactions should be reviewed for the details of any reserve release conditions.

Over-collateralization (OC) is the amount of collateral in the pool that is in excess of the ABS bonds issued. For example, if the total collateral pool is $500 million and the ABS issued is $450 million, then the OC would be $50 million, or 10% of the collateral pool. This form of credit enhancement may be preferred by an originator that does not want to tie up cash in a reserve fund.

Finally, subordination is the issuance of other classes of securities that would be junior in priority for receiving principal repayment. Many ABS transactions have rated subordinated classes that are sold to third-party investors. Most structures have ratings on these securities from AA to BBB, but it is not unusual to see a BB-rated class at the bottom of the capital structure. This allows an issuer to receive a higher advance rate against its pool of receivables, and it can reach investors with differing risk profiles.

Credit Analysis of ABS

The credit analysis of ABS is mainly focused on the performance of the collateral pool. Due diligence of the originator of the loans and its servicing capabilities are still an important component of any credit analysis, but for purposes of this chapter the focus remains on the collateral. Here we simply mention the key data needed to track performance.

Delinquency rates provide a signal of future losses, and in particular serious delinquencies of more than 60 days past due. Defaults, net losses, and loss severity/recovery rates are used by the rating agencies to help determine credit enhancement levels, and can be tracked over time to see if credit performance is in line with expectations. Prepayment rates should be followed because most financial obligations can be repaid early, and almost every ABS deal is priced based on some expected level of loan prepayments. The extent to which prepayments vary from expectations can have significant effects on the valuation of ABS.

Finally, most ABS transactions give the issuer the right, although not the obligation, to exercise a clean-up call of the collateral when the pool balance reaches some predetermined level. The call is usually set around 10% of the original collateral balance, although it is not unusual to see the clean-up call set from 5% to 15%. It is important to note that the call is on the collateral pool, and not on the outstanding ABS bonds directly. The call is in place because the fixed costs of servicing become a larger portion as the pool balance declines and it allows the servicer to manage its securitization costs. The history of an issuer’s clean-up call efficiency should be followed because the ability and willingness to exercise the call can have an impact on the valuation of ABS securities.

AUTO LOANS AND LEASES

One of the oldest and most active securitization sectors is the auto ABS sector. Since the 1980s, securitization has proved to be an attractive and efficient source of funding for auto finance companies. The auto ABS market has been predominantly based on auto loans to prime quality borrowers originated by the captive finance companies of large automakers. As investors showed growing acceptance of the ABS market during the 1990s, the economics of it brought new issuers that included smaller specialty finance firms as well as lenders to nonprime borrowers. Furthermore, consumers opted to lease new cars in increasing numbers over time, and this led to more auto lease ABS transactions. Auto ABS issuers can be divided into five broad groups: the Detroit Three, foreign automakers, bank lenders, independent finance companies, and subprime lenders. The auto finance sector has witnessed considerable consolidation over the years, especially among lenders to nonprime borrowers.

Auto ABS Structure

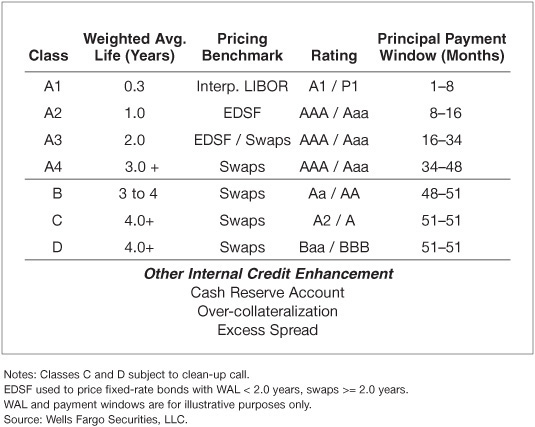

Auto loan ABS are typically issued using an owner trust structure, which is a legal form that allows for a time tranching of the senior class, as well as credit tranching to issue subordinated debt. The sequential senior bonds allow issuers to tailor issuance to meet the different maturity preferences of fixed income investors. For example, an auto owner trust may have a senior class that is divided into four subclasses as shown in Exhibit 34–2. The Class A1 tranche would be structured with a short average life and would typically meet the requirements for Rule 2a-7 eligibility so that money market investors could buy it.

EXHIBIT 34–2

Example Auto ABS Structure

In addition, there would be classes with one- and two-year average lives, as well as a last cash-flow (LCF) senior bond, with an average life of three years or more. The LCF senior bond tends to have a more limited investor base than the other senior bonds because this class may have greater variability in its expected maturity. One or more subordinated classes also may be offered, usually with ratings from AA to BBB.

The pricing benchmarks for fixed-rate auto ABS depend on the weighted average life (WAL) of the bond. For example, the money market tranche would be priced against an interpolated LIBOR rate. If the WAL is 0.30 years, then the yield would be based on an interpolated LIBOR rate between three and four months. For bonds with average lives of 2.0 years or longer, the swap curve normally would be used as the pricing benchmark for the auto ABS. Bonds with average lives less than 2.0 years use the Eurodollar synthetic forward rate (EDSF), which is the rate implied by the prices of Eurodollar futures. This curve may deviate from the interpolated LIBOR rate implied by the cash market.

Since the underlying loans make payments of principal on a monthly basis, the principal is returned to investors also on a monthly basis. This structural artifact creates a “payment window” for each of the bonds. For example, Class A2 has a principal payment window from month 8 to month 16—a nine-month payment window. This feature is unlike credit card ABS (discussed below), in which the bonds are structured with a bullet payment of principal at the expected maturity date.

Investors generally prefer tighter principal payment windows that allow for less uncertainty as to WAL and valuation. The return of principal to investors can be affected by prepayments and defaults by borrowers, as well as the exercise of the clean-up call option by the issuer. The Class A2 bonds tend to be the largest class in an auto loan ABS deal, and the majority of the total amount of the bonds issued tends to be in the top of the capital structure to minimize the cost of issuance.

EQUIPMENT LOANS AND LEASES

Equipment loans and leases were some of the earliest nonmortgage assets to be securitized, and tend to be structured in a similar way to that used in the auto ABS sector and displayed in the example in Exhibit 34–2. Furthermore, trading in these securities generally use the auto ABS market as a guide to pricing, with equipment ABS normally offering a concession to benchmark auto ABS securities. Equipment loan transactions tend to look much like other types of securitizations in which interest from the loans is used to pay interest to bondholders and principal is used to repay principal. The securitization of lease receivables presents another problem for the deal structure because leases do not carry any sort of explicit interest rate. As a result, the lease collateral pool is discounted at the weighted average coupon of the securities plus any servicing fees and other expenses to create an interest component on the collateral.

Equipment securitizations may be backed by loans or leases of different types of equipment that fall into three broad categories based on the original cost of the equipment. For example, small ticket equipment pools, such as telephone systems, computers, or copying machines, tend to have an original cost of less than $100,000; mid-ticket equipment pools, such as some medical or larger printing equipment, have an original cost of $100,000 to $500,000; and large ticket equipment pools, such as agricultural or construction equipment, have an original cost of greater than $500,000.1

From a credit perspective, analysis of equipment ABS may be relatively labor intensive because of the specialized nature of many types of equipment. In addition, residual values of the equipment are important in lease deals because some items, especially certain types of small ticket equipment, may depreciate more quickly than others. The degree to which any residual value realizations have been securitized and included in the cash-flows of the transaction can have a critical impact, particularly for tranches that pay later in the priority of the capital structure.

Equipment ABS issuers and sponsors in some cases may also be smaller, specialty finance firms without a corporate credit rating that use securitization for the bulk of their term funding. In other cases, the issuers are large manufacturers with their own corporate credit ratings that use securitization as one method of funding to diversify their sources of credit in the capital markets.

STUDENT LOANS

Student loan ABS became the largest individual sector of the ABS market in the fourth quarter of 2010 at $248 billion. This amount compared with $206 billion for credit cards and $127 billion for autos. The student loan sector saw issuance decline during the financial crisis, but the total amount outstanding stabilized largely because prepayment rates slowed. The character of the student loan market is likely to shift over time as funding for student loans migrates from the private market to direct government lending, which is unlikely to be securitized.

The student loan ABS market became so large in the first place because education costs have increased faster than the ability of students and parents to pay tuition. Some of this funding gap has been filled by student loans made by private lenders and guaranteed by the government, and also by private student loans with no guarantee. The student loan ABS market follows these two broad categories.

Government Guaranteed Student Loans

The Federal Family Education Loan Program (FFELP) provides loans to students and parents for postsecondary education. FFELP loans are originated by a lender, which may be a bank, insurance company, state agency, or not-for-profit student loan company. The loans carry a guarantee from the federal government that covers interest on the loan and repayment of principal up to 97% of the original loan balance. There are four different types of loans available under the FFELP plan: subsidized Stafford, unsubsidized Stafford, PLUS, and consolidation loans. Subsidized Stafford loans are made to students who meet a financial needs test. Unsubsidized Stafford loans are available to students who do not qualify for the subsidized loans or have needs beyond the subsidized loan limits. PLUS loans are made to parents of students. Student borrowers can combine Stafford and PLUS loans into one consolidation loan and make one monthly payment.

A student’s status in the school/repayment life cycle is a key factor determining the cash-flows in student loan ABS. When a Stafford loan is made and the student is enrolled in school, the borrower’s status is “in school.” The in-school period does not have a time limit, but would typically be one to four years depending on when the loan was made, the type of school, and the degree pursued. The in-school period is followed by a six-month grace period before the loan enters its repayment period. During the repayment period, the borrower is responsible for full payments of interest and principal on the student loans.

Borrowers with subsidized Stafford loans do not pay interest or principal during the in-school or grace periods, and the Department of Education makes the interest payments on behalf of the student during these periods. For unsubsidized Stafford loans, accrued interest is capitalized into the unpaid loan balance at the end of the status period. PLUS and consolidation loans enter into repayment of interest and principal 60 days after the funds are distributed to the student.

Once a borrower is in repayment, a loan can go into deferment or forbearance, which allows a borrower to delay payments of interest and principal. Deferment allows a borrower to postpone payments due to unemployment, economic hardship, entering public service, or the military. In these circumstances, deferment can be one to three years in length. For a borrower who goes on to further educational programs, there is usually no time limit on their deferment status. Forbearance may be used for borrowers who have lost a job or are having some other type of economic hardship. Forbearance may be granted in six- or 12-month periods, but the total time in forbearance cannot exceed three years. Different types of schools may carry different credit or prepayment risks. School types include two-year, four-year, graduate, and proprietary or for-profit schools.

Private Student Loans

The federal government has replaced the FFELP loans with direct lending from the government. Over time, the student loan ABS market should migrate toward more private loan deals. Private student loan ABS has generally been a very small sector in the past; however, as the cost of college rises, students and parents may need to tap other sources of funds to close the gap between cost and savings. Private student loans carry no federal government guarantee to compensate investors against defaults. In this regard, private student loans are more similar to other kinds of consumer credit, and pools of student loans are likely to be originated and serviced like other types of consumer ABS. One important difference, however, is that unlike other kinds of consumer credit, student loan debt cannot be discharged in bankruptcy. This factor provides some additional level of protection in terms of potential recovery on defaulted loans.

Private student loans may be disbursed directly to the student rather than through the financial aid office of the school. Direct-to-consumer (DTC) loans may show higher loss rates because the money never makes it to pay tuition, or because of the potential for fraud. Nevertheless, like government guaranteed student loans, the collateral performance of private student loans depend on a number of characteristics. Investors should look for investors that provide collateral pool information on the key risk factors in order to make an informed investment decision.

Like FFELP loans, the most significant collateral characteristics include the type of loan made for undergraduate, graduate school, proprietary/for profit, or a consolidation loan. The credit quality of the borrower very often using the FICO score is taken under consideration, as is whether the loan is cosigned by a parent or another party that may take responsibility for repaying the loan. As noted, if the borrower receives the loan directly from the lender, then it may have a higher risk profile than a loan that is channeled through the school. The type of school plays a role in the credit profile if it is a two-year, four-year, or for-profit school. Like other kinds of consumer credit, the loan seasoning can be an indicator of risk. Generally, a pool of loans with more seasoning tends to be less risky than a pool of loans with little or no seasoning. The loan status—in-school, grace, repayment, deferment, or forbearance—with their differing cash-flows may create different risk profiles for a transaction.

Student Loan ABS Structure and Risks

Student loan ABS structures, like all securitizations, are designed to mitigate risks and create a situation in which investors can be repaid and the rating agencies can achieve investment grade ratings on the securities. In student loan ABS, the major risks are credit losses, liquidity, servicing, and interest rate and basis risk. Credit risk can be mitigated through credit enhancement that protects investors against principal writedowns. Excess spread is the first line of defense against credit losses, and is generated when the yield on the loans is greater than the cost of the liabilities in the securitization. Credit enhancement may be in the form of over-collateralization or subordination that is in a position to absorb losses ahead of rated securities.

Liquidity risk can be particularly acute in student loan ABS because pools of student loans may have a substantial number of loans that are not yet in repayment status. Loans that are in-school, grace, deferment, or forbearance may not pay principal or interest and therefore can decrease the cash-flow available for ABS investors. Liquidity support may be provided by a capitalized interest account that can be used to pay interest to bondholders before loans enter their repayment status. In addition, a reserve account may be part of the deal structure to provide liquidity as well as credit enhancement, much as it would in any other sort of ABS deal. Such a reserve account would be funded at closing and have a minimum level to protect investors against losses.

Interest-rate risk and basis risk may be higher in student loan ABS than in most other segments of the ABS market. The reason is that the borrower’s interest rate may be either fixed or floating, and if floating it may be linked to a number of benchmarks, including the prime rate, Treasury bill, one-month LIBOR or three-month LIBOR. In most cases, the interest rate on the ABS is based on one- or three-month LIBOR. When both sides of the equation are floating, the interest-rate risk can be mitigated. However, there may be a mismatch in the timing when the interest rates on the loans reset compared with the reset on the ABS. This situation leads to the potential for the collateral pool to provide excess spread.

Servicer risk is an important component of a securitization because the lender originates the collateral, is responsible for adequate underwriting, and then must have the capabilities to collect the interest and principal from borrowers and minimize the losses from defaults. On a student loan ABS deal backed by FFELP loans, the collateral pool has the benefit of the government guarantee, so losses would be mitigated through the guarantee. However, the servicer must comply with the rules and regulations set down by the Department of Education in order to get the full benefit of the guarantee for the ABS investors. Private student loans do not have the benefit of a government guarantee, so the underwriting and servicing of the loans must stand on the lender/servicer ability to collect on the loans. The ability of borrowers to delay repayment through various stages of the student loan life cycle suggests that the capability of the servicer can play an important role in the long-run quality of student loan ABS.

KEY POINTS

• Securitization is a process where the cash-flows from financial assets—interest and principal—are used to back payments on securities sold to investors.

• Assets securitized are primarily loans and leases, but many other types of receivables and financial obligations, such as accounts receivable or utility charges, have found their way into the ABS market.

• Securitizations are usually structured as bankruptcy-remote vehicles to isolate the assets from any potential bankruptcy of the originator. This bankruptcy remoteness allows the ABS debt to carry credit ratings that may be higher than those of the originator of the assets backing the securities sold to investors. The vast majority of ABS sold to investors, in fact, carry a AAA rating from one or more credit rating agencies.

• Credit enhancement in the form of over-collateralization, excess spread, subordination, and/or cash reserve accounts may be used in combination to protect investors against credit writedowns on their bonds.

• The credit analysis of ABS is based primarily on the delinquencies, defaults, prepayments, and historical cash-flows of the underlying collateral. The credit quality of the originator of the assets plays an indirect role since the servicing of the collateral pool is important for maximizing the value for investors.

• Outside of the credit card ABS sector, the largest segments of the market are auto loans and leases, equipment loans and leases, and student loans.

• The structures of different ABS asset classes will depend upon the cashflow profile of different kinds of loans or leases. Structures will be put together to mitigate risks that may be unique to each different type of asset class.