Actor-network theory

An alternative approach

This chapter proposes ANT as an alternative approach for understanding both information practices and practices of nationalism and cosmopolitanism. ANT does not offer another compromise between individual and collective, micro and macro, local interaction and global context, but it argues that these dichotomies should be ignored as they are merely effects of completely different phenomena – associations. The neologism of information cosmopolitics is introduced to describe information practices as a continuous circulation of processes of individualisation and collectivisation – a constant negotiation (thus politics) between heterogeneous (human and non-human) actors in the process of composing a common world (a cosmos) in which individual and collective constantly exchange properties.

Keywords

Actor-network theory; information cosmopolitics; individualisation; collectivisation; cosmos; politics

The previous chapter has identified difficulties in studying information practices and practices of nationalism and cosmopolitanism. Scholars from these fields oscillate the focus of their theoretical attention between the individual and collective, so that the discourses of these fields are dominated by dichotomies such as individual/collective, particular/universal, local/global, and technological/social. Somerville (1999) argues that this dualism is an effect of the modernist preoccupation with the notion of identity and ‘a radical separation of the world in the “human”, the “natural” and the “technical”… [leading]…ultimately to questions as to the essential nature, or identity, of each’ (p. 8). For Murdoch (1997) this perspective is problematic because it leads to a fragmented view of the world, creating a gap ‘between rich descriptions of ways of life and the means by which these are encompassed within strong explanatory frameworks’ (p. 323). Understanding the complex social, political and technological negotiations involved in scholarly information sharing requires a theoretical approach that is able to avoid this gap. ANT is described by Somerville (1999) as an approach that ‘offers a more coherent way of describing or narrating a complex world’ (p. 11).

ANT emerged during the 1980s within the sociology of science and technology, with the work of Bruno Latour, Michael Callon and John Law. One of the main assumptions of ANT is that science is the process of heterogeneous engineering in which social, natural and discursive are puzzled together in the process of translation. This opposes both social and technical determinism and proposes a socio-technical approach in which nothing is purely social or purely technical (Law, 1992). Early on, Callon (1986b) proposed three basic methodological principles of ANT: agnosticism, generalised symmetry and the principle of free association. Agnosticism advocates that all a priori assumptions of the nature of networks or accuracy of the actors should be abandoned, and that no interpretation should be censored (Callon, 1986b). ANT researchers ask for the inclusion of a number of entities that were missing in sociological accounts (Callon & Law, 1997) and the making of a list, no matter how long and heterogeneous, of actors that make action possible (Latour, 1987, 2005). Generalised symmetry advocates the use of the same type of analysis for all elements of network whether they are natural or social. The single explanatory framework should be used for interpretation of actors, both humans and non-humans. The principle of free association abandons any distinction between social and natural, and instead it views these distinctions as the effects of the network activities.

Each of these principles has been questioned and criticised. For instance, Bloomfield and Vurdubakis (1999) question possibilities of agnosticism in selecting the actors – possibilities to ‘represent Other times and Other places with only the tools of the Here and Now’ (p. 631). Star (1991) claims that ANT neglects entities that do not have access to the stabilised networks of humans and non-humans in its focus on a ‘managerial and entrepreneurial model of actor networks’ (p. 26). Another criticism of ANT is a failure to examine moral and political issues (McLean & Hassard, 2004, p. 510). Law (1992) responds that the principle of free association is not an ethical position, but an analytical stance. He claims that ‘to accept the reality of epistemological relativism and deny that there are universal standards is not to say that there are not standards at all: and neither is it to embrace moral or political relativism’ (Law, 1991, p. 5, emphasis in original). The principle of generalised symmetry is criticised as unattainable by Collins and Yearley (1992) who claim that ANT studies provide an essentially human-centred account since the non-human actors are represented by human researchers. However, Callon and Latour (1992) argue that the focus of ANT’s empirical methods is on ‘the traces left by objects, arguments, skills, and tokens circulating through the collective’ (p. 351). The aim of the principle of general symmetry is ‘not to alternate between natural realism and social realism but to obtain nature and society as twin results of another activity’ (p. 348), which is the network building.

Callon and Latour (1992) suggest that much of the early criticism of ANT could be a result of misunderstanding. They clarify that their intention was not to claim that scallops could exercise voting power, or that automatic door closers are entitled to social benefits, ‘but that a common vocabulary and a common ontology should be created by crisscrossing the divide by borrowing terms from one end to depict the other’ (p. 359). In order to clarify basic ANT concepts, Akrich and Latour (1992) propose A Summary of a Convenient Vocabulary for the Semiotics of Human and Nonhuman Assemblies. However, a few years later, Latour (1999a) attempted to recall these basic concepts as inadequate to their original intention to give actors a space to present their own theories, suggesting instead ‘abandoning what is so wrong with ANT, that is ‘actor’, ‘network’, ‘theory’ without forgetting the hyphen’ (p. 24). Finally, in 2005, Latour (2005) recognised that ANT itself became a stabilised name and note that the acronym A.N.T. could actually be a perfect name to describe an approach that like an ant is ‘a blind, myopic, workaholic, trail-sniffing, and collective traveler… a name that is so awkward, so confusing, so meaningless that it deserves to be kept’ (p. 9). This chapter proposes ANT as an alternative approach for understanding both information practices and practices of nationalism and cosmopolitanism. The first two sections describe the basic ANT concepts – actor, network, theory, including the hyphen, without forgetting the principles of this ‘sociology of associations’ – before they can be fully deployed by the study. Finally, the chapter discusses the ways that such an approach can be used for understanding nationalism and cosmopolitanism, and the neologism ‘information cosmopolitics’ is introduced to describe information practices as circulation of hybrid entities continuously exchanging properties.

Actor, network, theory, without forgetting the hyphen

Actor is any agent, collective or individual, that can associate or disassociate with other actors. One of the feature of ANT ‘is that actors, the components of network, may be more or less, interchangeable, people, animals, plants, organisations, machines, events or ideas’ (Underwood, 2002), or consumers, social movements, ministries, accumulators, fuel cells, electrodes, electrons, and catalyst (Callon, 1986a). This feature offers advantages over other approaches in avoiding assigning an ‘essence’ to humans, nature, or technology. Verbeek (2005) points out that actors should not be seen as free-standing entities that enter into relations with each other, because that will mean that they ‘have a pre-established essence, which Latour rejects’ (p. 149). Callon (1986a) points out that the actors could not be classified based on their essence, so ‘the activist in favour of public transport is just as important as lead accumulators which may be recharged several hundred times’ (p. 23). Since the word actor is frequently used to refer exclusively to humans, the term actant ‘is sometimes used to include non-humans in the definition’ (Latour, 1999b, p. 303). By eliminating the human/non-human binaries, ANT enables technological artefacts to act, move and speak (Kim & Kaplan, 2005). The history and size of entities are determined by relations with other entities. An actor is not just a point object or a placeholder (Latour, 2005), but it is an association of heterogeneous elements, so that each actor is also a simplified network (Law, 1992). For ANT, an actor or actant is ‘something that acts or to which activity is granted by others… [which]… can literally be anything provided it is granted to be the source of an action’ (Latour, 1996a).

In the same way in which an actor consists of a network of interactions and associations, a network may be simplified, or black-boxed, to look like a single point actor (Law, 1992). The word network came from the attempt to describe society not as two-dimensional or three-dimensional but ‘in terms of nodes that have as many dimensions as they have connections’ (Latour, 1996a). It is a concept rather than a thing: It is a tool to help describe something, not what is being described (Latour, 2005). With this tool, it is possible to describe issues that have no similarity to the shape of networks such as a government policy or a symphony orchestra; however, ‘you may well write about technical networks – television, e-mails, satellites, salesforce – without at any point providing an actor-network account’ (p. 131). The power of the network metaphor is that it leaves the spaces ‘in between’ empty rather than filling them with ‘social stuff’. In such a projection, the size and significance of an actor is not predetermined, but it is an effect of network building. The notion of network enables ANT to replace spatial metaphors such as close/far, up/down, local/global and inside/outside with associations and connections which are not exclusively social, natural or technical (Latour, 1996a).

Callon (1986a) introduces a concept of actor-network, which ‘allows us to describe the dynamics and internal structure of actor-worlds’ (p. 28). The concepts of actor and network in the term actor-network are both related and distinguished by the hyphen. The hyphen could be seen as ‘an unfortunate reminder of the debate between agency and structure’ (Latour, 1999a, p. 21), the debate that ANT explicitly tries to ignore ‘by simultaneously viewing actors as purposeful subject and network effects’ (Kim & Kaplan, 2005, p. 169). Law (1999), however, argues that the concept of actor-network should be seen as a term that is intentionally oxymoronic, embedding a tension between the centred ‘actor’ and the decentred ‘network’ – it ‘is thus a way of performing both an elision and a difference between what Anglophones distinguish by calling ‘agency’ and ‘structure’’ (p. 5). While the hyphenated term made it difficult to see, the intention of ANT is not ‘to occupy a position in the agency/structure debate, not even to overcome this contradiction’ (Latour, 1999a, p. 16, emphasis in original). Instead, ANT strategy is to ignore it, and focus on movement that leads social scientists to constantly shift their focus between local interactions and social structure.

This movement, captured by the concept of actor-network, has three important consequences. First, the network does not describe the macro-social, but refers to ‘the summing up of interactions through various kinds of devices, inscriptions, forms and formulae, into a very local, very practical, very tiny locus’ (p. 17, emphasis in original). Second, ‘actantiality is not what an actor does… but what provides actants with their actions, with their subjectivity, with their intentionality, with their morality’ (p. 18, emphasis in original). Third, actor does not play the role of agency, nor the network play the role of social structure. Rather they ‘designate two faces of the same phenomenon, like waves and particles, the slow realization that the social is a certain type of circulation that can travel endlessly without ever encountering either the micro-level – there is never an interaction that is not framed – or the macro-level – there are only local summing up which produce either local totalities (oligoptica) or total localities (agencies)’ (p. 19, emphasis in original).

An actor-network is traced whenever, in the course of a study, the decision is made to replace actors of whatever size by local and connected sites instead of ranking them into micro and macro. The two parts are essential, hence the hyphen. The first part (the actor) reveals the narrow space in which all of the grandiose ingredients of the world begin to be hatched; the second part (the network) may explain through which vehicles, which traces, which trails, which types of information, the world is being brought inside those places (Latour, 2005, p. 179).

The network is a concept to designate relationalities rather than structures, and an entity is an actor only in relations to other entities. An actor is an effect of these relations. Thus, the hyphen can be seen as a relation, which indicates that both actor and network are essential for the concept of actor-network (Latour, 2005, p. 179). An actor-network ‘is simultaneously an actor whose activity is networking heterogeneous elements and a network that is able to redefine and transform what it is made of’ (Callon, 1987, p. 93). It is ‘a way of talking about and exploring radical relationality’ (Law, 2000). ANT is an approach that is not based on pre-existing social categories such as class and gender. Law (2000) points out that a major argument of ANT is that all entities are initially equal and indeterminate. This does not mean that differences do not exist, but if they exist it is because they are created in the relations to other entities, not because they were in some ‘order of things’ (Law, 2000). This assumption has an impact on how ANT analysts conduct research and the focus of their research. The task of analyst is to explore entities brought into being by those relations, as ANT ‘is a method (or better, a sensibility) that has to do with and explores relations, relationality’ (Law, 2000).

ANT is considered by many authors as an analytical method rather than a coherent theory. For Callon (1999), the T is too much in the acronym ANT since it is not a theory, and this is what gives ANT ‘both its strength and its adaptability’ (p. 194). The term theory ‘suggests precisely the opposite of what ANT seeks to do: to trace entities as they move through networks of relations’ (Verbeek, 2005, p. 151). Latour claims that if ANT is a theory of anything, it is a theory about how to study things, or better how not to study things, ‘or rather, how to let the actors have some room to express themselves’ (Latour, 2005, p. 142). It is ‘simply a way for the social scientists to access sites, a method and not a theory, a way to travel from one spot to the next, from one field site to the next, not an interpretation of what actors do’ (Latour, 1999a, pp. 20–21, my emphasis).

Far from being a theory of the social or even worse an explanation of what makes society exert pressure on actors, it always was, and this from its inception, a crude method to learn from the actors without imposing on them an a priori definition of their world-building capacities (Latour, 1999a, p. 20).

The main methodological prescription of ANT is to ‘follow the actors’. ANT uses ‘some of the simplest properties of nets and then add to it an actor that does some work’ (Latour, 1996a). Latour (2005) stresses that the focus of research should be on work, movement, flow, and changes rather than actors and networks as placeholders. Hence he suggests that the term ‘worknet’ might be more appropriate than network, as ‘[w]ork-nets could allow one to see the labor that goes on in laying down networks: the first as an active mediator, the second as a stabilized set of intermediaries’ (p. 132).

‘When your informants mix up organization, hardware, psychology, and politics in one sentence, don’t break it down first into neat little pots; try to follow the link they make among those elements that would have looked completely incommensurable if you had followed normal procedures.’ That’s all. ANT can’t tell you positively what the link is (Latour, 2005, pp. 141–142).

ANT is sometimes referred to as the ‘sociology of translation’ (Callon, 1986b; Law, 1992). The concept of translation suggests that there is no social force in interactions that would be simply transported to actors and would determine their actions, but rather that different interests of heterogeneous actors are translated into a new composite goal. Translation is defined by Callon (1986b) as means of obliging some entity to consent to a ‘detour’, which is then able to speak on behalf of other actors enrolled in the network. In this process of taking detours through the goals of others, the language of an actor is substituted for the language of another actor, which ‘implies transformation and the possibility of equivalence, the possibility that one thing (e.g. an actor) may stand for another (for instance a network)’ (Law, 1992). Translation thus has both linguistic and geometric meaning, since to translate different interests into new goals ‘means at once offering new interpretations of these interests and channelling people in different directions’ (Latour, 1987, p. 117).

Latour (1987) describes five translation strategies that actors use to enrol other actors to their networks. Latour defines translation 1 as ‘I want what you want’. The easiest way to enrol people into a network is to align to other people’s explicit interests, so that the interests of those who enrol and those being enrolled ‘are moving in the same direction’ (p. 109). For example, this strategy could be employed in academic communities when scholars need access to sources and equipment, establishment in a discipline or an institution, when they want to create useful alliances, or when they share common public concerns. However, simply aligning ‘to other explicit interests is not a safe strategy’ (p. 111), as it does not provide any control over network building. Translation 2 ‘I want it, why don’t you?’ provides maximum control but is very rare. Others could be enrolled in such a network only in situations when their usual way is cut off. In academic collaboration, scholars could use it in situations when they are strong, for example, when they have a special access to instruments, or a position in the field or institutions; but also when they are weak desperately trying to mobilise public opinion or enrol powerful alliances. Translation 3 ‘if you want to make a short detour’ refers to situations when actors try to convince others that they will reach their goals faster by offering them a guide through a shortcut. There are three conditions to convince others to take the short cut: the actors’ way ‘is clearly cut off; the new detour is well signposted; the detour appears short’ (p. 112). Scholars often make detours by aligning their interests to the interests of other academics in order to use their information sources. They could also shift their claims to fit to a public or domain discourse, as well as to attract alliances. Translation 4 ‘reshuffling interests and goals’ refers to tactical movements to change other actors’ interests including displacing goals, inventing new goals, and inventing new groups. In order to make this strategy successful, it is necessary to render the detour invisible, ‘so that the enrolled group still thinks that it is going along a straight line without ever abandoning its own interests’ (p. 116, emphasis in original). By rendering the detour invisible, it becomes impossible to identify ‘who is enrolled and who is enrolling’ (p. 118). Translation 5 or ‘becoming indispensable’ deals with situations when ideas or innovations become indispensable, so that no further translation is necessary. It could be said that all translations lead to translation 5, shifting the actors ‘from the most extreme weakness – that forced them to follow the others – to the greatest strength – that forces all the others to follow them’ (p. 121). From this point, innovations are seen as black boxes.

This, then, is the core of the actor-networks approach: a concern with how actors and organisations mobilise, juxtapose and hold together the bits and pieces out of which they are composed; how they are sometimes able to prevent those bits and pieces from following their own inclinations and making off; and how they manage, as a result, to conceal for a time the process of translation itself and so turn a network from a heterogeneous set of bits and pieces each with its own inclinations, into something that passes as a punctualised actor (Law, 1992).

Black box is a concept, which is used in ANT to describe ‘either a well-established fact or an unproblematic object’ (Latour, 1987, p. 131) – a network that, simplified through translation, can act as a single-point punctualised actor. Punctualisation is a precarious effect of simplification that ‘converts an entire network into a single point or node in another network’ (Callon, 1991, p. 153), which makes unity appear and network complexity disappears (Law, 1992). However, black boxes can be disbanded at any moment because a network is only as strong as its weakest link (Latour, 1987, p. 121). A network is not durable only because of the strong bonds between the points ‘but also because each of its points constitutes a durable and simplified network’ (Callon, 1986a, p. 32). The social structure is then a verb rather than noun – an effect of the process of punctualisation – which suggests that there is no social order with a single centre, but there are only orders in the plural (Law, 1992).

This is where ANT strongly distinguishes itself from traditional sociology. While traditional sociology proposes that social structure stands for stabilised states of affairs made of ‘social’ stuff, ANT ‘claims that there is nothing specific to social order; that there is no social dimension of any sort, no “social context”, no distinct domain of reality to which the label “social” or “society” could be attributed’ (Latour, 2005, p. 4). Instead, ANT focuses on movements, relations and connections between heterogeneous entities. A crucial point of departure between a traditional and an ANT approach is that while for the first approach every activity ‘could be related to and explained by the same social aggregates behind all of them… [for ANT]… there exists nothing behind those activities even though they might be linked in a way that does produce a society – or doesn’t produce one’ (p. 8, emphasis in original). Latour argues that the first approach has confused ‘the cause and the effect, the explanandum with the explanans’ (p. 63, emphasis in original). Social is seen to be always already there, while for ANT the social ‘is visible only by the traces it leaves (under trials) when a new association is being produced between elements which themselves are in no way “social”’ (p. 8, emphasis in original). Thus the focus of the first approach is on social as a specific domain of reality, while the focus of ANT is on heterogeneous assemblages, recognising ‘that the social is revealed most clearly by processes of assembly, whether in building associations between disparate kinds of elements, or when such associations break down, are interrupted or transformed from one assemblage to another’ (Frohmann, 2007, p. 5). To clarify distinctions between the two approaches, Latour (2005) describes the first approach as ‘sociology of the social’, and the second as ‘sociology of associations’.

Sociology of associations

Latour (2005) proposes that sociology of association should take three different duties in succession: deployment, stabilisation and composition. First, it deploys controversies in order to include a range of participants in any assemblage. Then, it follows the actors themselves as they stabilise the controversies. And finally, it deals with a question of ‘political epistemology’ (Latour, 2004b) in order ‘to see how the assemblages thus gathered can renew our sense of being in the same collective’ (Latour, 2005, p. 249). For the sociology of association ‘essence is existence and existence is action’ (Latour, 1999b, p. 179). By shifting attention from the essence of actors to associations, this approach will enable the present study to trace scholarly information sharing in making. This section will thus focus on the task of stabilisation – on the ways to follow actors themselves stabilising the social by building formats and standards through heterogeneous associations. In order to make visible these associations, these chains of translation in which phenomena circulate (p. 72), Latour (2005) proposes keeping the social flat. But first, an analyst should deploy five major controversies about the social in order to ‘renew our definition of what is an association’ (p. 21).

Deploying controversies

A controversy enables exploration of possible actors, problems and solutions, which would otherwise be excluded or not taken in account. As such, the exploration of controversies ‘constitutes a process of collective learning’ (Callon, Lascoumbes, & Barthe, 2009, p. 32). They help to reveal both new emergent actors created by a controversy, and previously invisible actors that ‘take advantage of the controversy to enter the scene in a legitimate role’ (p. 29). First, ANT proposes mapping the controversies about group formation rather than defining in advance relevant groups that provide a social context. Groups are seen as constantly changing associations of actors, rather than stable entities, which means that there is ‘no group, only group formation’ (Latour, 2005, p. 27). As the group formation is always in progress, an actor may belong to a number of groups, and group membership is not predetermined. Rather the actors are constantly being enrolled or enrolling other actors to a group. It seems that ‘sociology of the social’ tries to avoid this uncertainty of group formation by accepting the convenience of tracing already stabilised groups. However, this ‘convenience’ makes it difficult to trace associations because an already stabilised group is by definition mute and invisible, and it ‘generates no trace and thus produces no information whatsoever’ (p. 31). On the other hand, group formations and related processes of inclusion and exclusion of the group members enable tracing of associations.

For example, group formations leave traces of spokespeople as there is no group ‘without a rather large retinue of group makers, group talkers, and group holders’ (p. 32). Then, tracing the boundary of a group always illuminate traces of another group or a set of anti-groups, which ‘means that actors are always engaged in the business of mapping the “social context” in which they are placed, thus offering the analyst a full-blooded theory of what sort of sociology they should be treated with’ (p. 32). It is important to be aware that when groups are formed, their spokespersons (including social scientists) constantly mark their boundaries, and render them fixed and durable, appealing to tradition, law, genetics, blood, soil, emancipation, history, etc. Once the group is made unquestionable and taken for granted, it becomes a bonafide member of the social, in the usual sense; however, in the ANT sense, it is removed from the social world because it no longer produces ‘any trace, spark, or information’ (p. 33). In the ANT sense, the social connections that form social groups do not exist on their own. Without constant work on group formation, there is no group. There is no ‘social inertia’ nor reservoir of ‘social forces’ that keeps social groups stable. While the sociology of the social uses already stabilised groups to explain things, ANT ‘views stability as exactly what has to be explained’ (p. 35).

Second, action is not predetermined by some social forces or individual actors, but it is rather dislocated. This explains ANT’s understanding of agency. The hyphenated expression actor-network does not designate an actor as a source of action but rather that action ‘is borrowed, distributed, suggested, influenced, dominated, betrayed, translated’ (p. 46). While ANT agrees with the sociology of the social that in most interactions, action is overtaken by some other places and times, it does not agree that a social force has taken over, or that the agencies overtaking the action are necessary social. It is crucial for an ANT account to start from uncertainty and under-determination of action and to ‘follow the actors’ and traces they leave. This is not ‘because actors know what they are doing and social scientists don’t, but because both have to remain puzzled by the identity of the participants in any course of action if they want to assemble them again’ (p. 47).

In order to map the controversies over agency, we should take into account features of ‘contradictory arguments about what has happened: agencies are part of an account; they are given a figure of some sort; they are opposed to other competing agencies; and, finally, they are accompanied by some explicit theory of action’ (p. 52). Agencies are always presented as doing something and leaving material traces. An agency that is not visible, ‘that makes no difference, produces no transformation, leaves no trace, and enters no account is not an agency’ (p. 53). Agencies are always given a figure or shape of different sorts, none of them are more concrete, abstract, realistic or artificial: ‘ideo-, or techno-, or bio-morphisms are ‘morphism’ just as much as the incarnation of some actant into a single individual’ (p. 54). Agencies are opposed by other competing agencies, so the actors are constantly engaged in adding new entities as legitimate agencies. So, any agency, when provided with existence, figuration and opponents could be treated as an intermediary or as a mediator, no matter what its figuration is. ANT treats actors as mediators, that is full-blown metaphysicians with not only ‘their own meta-theory about how agency acts, [and]… which agency is taking over but also on the ways in which it is making its influence felt’ (p. 57).

Third, objects have an agency and they participate in action to make social ties durably expanding. This is probably the most debated controversy between ANT and traditional social science. While traditional sociology recognises a role that material objects play in social relations, it assumes that non-human materials have a different status than the status of the humans. The non-human objects are treated as passive resources or constraints, which could be activated only when mobilised by human actors. As such, objects could be at best contextual elements, but they cannot have the status of actors. It is thus a usual analytical practice of the sociology of the social to purify heterogenous networks by distinguishing human subjects from non-human objects. For instance, when the sociology of the social encounters a hybrid such as a ‘gunman’, its first reaction is to separate the man as a subject and the gun as an object. This then initiates an absurd debates between those with a ‘materialist explanation’, who would claim that ‘guns kill people’ suggesting that guns act regardless of social qualities of gunmen, and those with a ‘sociological explanation’, claiming that ‘people kill people’ depending on their morality (Latour, 1999b). The third option is to make some dialectic compromise and to claim that both guns and people kill people. However, instead of making a compromise, the connector ‘and’ even further distinguishes material and social, subject and object, humans and non-humans. Latour (2005) claims that an ANT approach is not to say that non-humans and humans are the same, but just ‘because they are incommensurable that they have been fetched in the first place’ (p. 74). It is precisely this difference that connects them together since without the material quality of non-humans, social ties would not be durable. Gunman is not merely a combination of a gun and a man. It is neither gun nor man, but a completely new hybrid entity. The heterogeneous network of gunman suggests that the gun in the term gunman ‘is no longer the gun-in-the-armory or the gun-in-the-drawer or the gun-in-the-pocket, but the gun-in-your-hand, aimed at someone who is screaming’ (Latour, 1999b, pp. 179–180). Neither gun nor man remains the same after being translated into gunman.

Both materialist and sociological explanations make the same mistake by assigning essences to subjects and objects that is to humans and non-humans. Entities have propositions rather than essences, and when these ‘propositions are articulated, they join into a new proposition’ (p. 180). Thus in the case of gunman, a good citizen becomes a bad guy, and a sporting gun becomes a weapon. The power cannot be explained as some mysterious force that makes someone do something, but as a mediation of heterogeneous entities into new propositions. This is why Latour (2005) argues that Marxian types of materialism, the critical sociologies of Pierre Bourdieu and Erving Goffman’s interactionist accounts are not wrong by themselves, but ‘[n]one of them are sufficient to describe the many entanglements of humans and non-humans’ (p. 84). Instead, the task of sociology should be ‘to characterise these networks in their heterogeneity, and explore how it is that they come to be patterned to generate effects like organization, inequality, and power’ (Law, 1992). To make the entanglements of humans and non-humans visible, the ANT analyst should pay close attention to the sites of innovation, learning, process breakdowns, records, but also fictions of possible crises, since sociology of association is not possible ‘if the question of who and what participates in the action is not first of all thoroughly explored, even though it might mean letting elements in which, for lack of a better term, we would call non-humans’ (Latour, 2005, p. 72).

Fourth, ANT rejects the proposition that multiplicity is a domain of social scientists while unity is the domain of natural scientists. It rejects a desire of both social and natural scientist, based on the purification of the ‘modern constitution’, for access to an ‘immediate world’, without any mediators, in which natural scientists speak for ‘naked facts’, while social scientists speak for ‘naked citizens’ (Latour, 1993). By introducing ‘matter of concern’ to replace ‘matter of facts’, Latour (2005) shifts mediators into the foreground and breaks down the modernist dichotomy between facts and values, emphasising uncertainties in knowledge and fact production since ‘things could be different, or at least that they could still fail – a feeling never so deep when faced with the final product, no matter how beautiful or impressive it may be’ (p. 89). For ANT, matters of fact are a premature unification of nature, a mute version of matters of concern. When the work of mediators is moved to the foreground, a mute fact becomes a matter of concern, ‘a visible locale endowed with a multitude of voices’ (Mitew, 2008b).

But this multiplicity is not a result of ‘interpretive flexibility’ where a multitude of voices reflects different points of view on the same thing. A thing itself is endowed with multiplicity. When ANT introduces matters of concern to prevent a premature unification of nature, it does not seek to add multiplicity to things, but to argue ‘that multiplicity is a property of things, not of humans interpreting things’ (Latour, 2005, p. 116). For ANT facts are fabricated and constructed, but this does not mean that they are ‘socially constructed’, that the reality is made ‘artificially’ of some ‘social stuff’ (p. 91). The concepts of constructivism and matter of concern are rather used ‘to describe the striking phenomenon of artificiality and reality marching in step’ (p. 90), to describe at the same time heterogeneity and gathering of the world: ‘Give me one matter of concern and I will show you the whole earth and heavens that have to be gathered to hold it firmly in place’ (Latour, 2004d, p. 246). So, in a good ANT account, ‘when agencies are introduced they are never presented simply as matters of fact but always as matters of concern, with their mode of fabrication and their stabilizing mechanisms clearly visible’ (Latour, 2005, p. 120).

Finally, the very making of reports is brought to the foreground. This fifth uncertainty of writing down ‘risky accounts’ extends the first four uncertainties and ‘the exploration of the social connections a little bit further’ (p. 128). The good report is an artificial experiment that replicates the traces of actors becoming mediators and mediators turning into intermediaries. Objectivity of an ANT account is not obtained by ‘objectivist’ style, but by the presence of many ‘objectors’ (p. 125). A textual account is like a laboratory, and it is as risky as any scientific experiment. As ANT considers social as a network, which is not a thing but ‘the trace left behind by some moving agent’ (p. 132) or an assembly, a good account is thus one that traces or reassemble a network ‘where each participant is treated as a full-blown mediator’ (p. 128). A good ANT account is a description of an actor-network rather than a social explanation. The misconception of the term description is often generated by its interpretation as ‘mere description’. So, when Latour says that only bad description needs an explanation, he understands description as a deployment of actors as a network of mediation, which ‘is not the same as “mere description”, nor is the the same as “unveiling”, “behind” the actors’ backs, the “social forces at work” (p. 136). On the contrary, description is ‘the highest and rarest achievement’ (p. 137).

There is no dichotomy between description and explanation. Description is already an explanation. Description is de-scription of in-scription. For instance, Akrich (1992) points out that for de-scription of technological objects ‘we need mediators to create the links between technical content and user’ (p. 211). De-scription is tracing negotiations between designers (inscribing their propositions into new technical objects) and real users rather than projected users, i.e., ‘between the world inscribed in the object and the world described by its displacement’ (p. 209, emphasis in original). The actors are already in-scribed with interpretations. They have their own theories and meta-theories as they are ‘full-blown reflexive and skilful metaphysicians’ (Latour, 2005, p. 57). Adding to these theories or replacing them will turn actors from mediator to intermediaries that do nothing but just sit there (p. 128), and consequently there will be nothing to be described, since traces of actors’ own stabilisation of controversies remain invisible.

Stabilising controversies

The major difficulty for social scientists to render the social traceable is ‘in locating their inquiries at the right locus’ (Latour, 2005, p. 164). When they focus on local interactions, they are asked to put things in their wider context; but when they reach a global context, they are requested to jump back from abstract structure to real life of local interactions (p. 168). Instead of jumping from one level to another, or to make a compromise between the two, Latour suggests that analysts should keep the social flat and leave the actors to define relative scale instead of the analysts defining an absolute one before doing the study. Scale is ‘what actors achieve by scaling, spacing, and contextualizing each other’ (p. 184). In order to follow the actors themselves stabilising controversies, ANT tries to keep these sites side by side, making the connections between them visible. To do so, Latour introduces conceptual tools that he calls ‘a series of clamps to hold the landscape firmly flat’ (p. 174) and proposes three moves to flatten the landscape of social: localising the global, redistributing the local and connecting the sites revealed by the first two moves.

The first move aims to break down the automatism that leads from local interactions to a global context. Localising the global means ‘to lay continuous connections leading from one local interaction to the other places, times, and agencies through which a local site is made to do something’ (p. 173). Two clamps that illuminate these connections are oligopticons and panoramas. Oligopticons, in contrast to panopticons, ‘see much too little to feed the megalomania of the inspector or the paranoia of the inspected, but what they see, they see it well’ (p. 181). An oligopticon is obtained by asking questions such as: in which place are the structural effects produced, in which office, which institution, etc.? The answers to such questions lead us to specific local places and institutions where the global is manufactured, highlighting ‘all the connections, the cables, the means of transportation, the vehicles linking places together’ (p. 176). It enables the analysis to ‘replace some mysterious structure by fully visible and empirically traceable sites’ (p. 179). For example, it enables us to replace an untraceable entity such as capitalism with a fully visible site such as a Wall Street trading room. This trading room, this oligopticon, is not bigger or above the local interactions in a specific company, but it benefits from safer connections with many more places. Thus, oligopticons keep the social flat by staying ‘firmly on the same plane as the other loci which they were trying to overlook or include’ (p. 176).

Panorama is another clamp that enables localising the global. It refers to actors’ own contextualising. Panorama brings into the foreground this activity of contextualising, the actors’ constant activity of framing things into some context. Panorama, in contrast to an oligopticon, is an attempt to see everything, to paint a ‘big picture’, to provide a prophetic preview of the collective. However, it is ‘misleading if taken as a description of what is the common world’ (p. 189), since panorama is merely a big picture painted by the actors in some specific places. Such a definition of panorama leads to questions such as: ‘in which movie theatre, in which exhibit gallery is shown? Through which optic is it projected? To which audience is it addressed?’ (p. 187).

The second move is to redistribute the local which deals with the ways the local itself is being generated. Another pair of clamps is introduced by Latour to illustrate these movements: localizers and plug-ins. Localizers or articulators are defined as ‘the transported presence of places into other ones… which have been brought to bear on the scene through the relays of various non-human actors’ (p. 194). The local place is localised by some other places through the mediation of objects. Objects can act in the absence of those whom they serve and format the local place for a generic individual. An example of the localizer is a speed-bump or a ‘sleeping policeman’, which performs an action in the absence of a real policeman.

A clamp that explains the circulation of subjectivities, individuality, personhood, interiority, and cognitive abilities, Latour calls ‘plug-in’, although it could be called subjectifier, personalizer, or individualizer (p. 207). He intentionally used a web metaphor to illustrate that individuals can download a plug-in from an institution, which will provide them with a temporary competence for a specific situation, and then make way for another plug-in connecting to another institution. By downloading some cultural clichés, individuals are provided with competences to create an opinion of a book, to have a political stance, or to know to which group they pertain (p. 209). Someone is an individual only if she or he has been individualised by downloading individualizers from the outside. But the outside has different meaning in this flattened projection. The outside is not a social context which determines the inside, but it is another local place to which an actor can be plugged-in. Plug-ins do not have ‘the power to determine, they can simply make someone do something’ (pp. 214–215), and ‘making do’ is not the same as causing, dominating, or limiting (p. 217).

The third move is connecting the sites revealed by the first two moves. Every time we localise the global or redistribute the local, a connection has to be established, transforming the sites to actor-networks. So, connections are brought into the foreground, and sites are moved to the background. The aim of this move is to follow the actors in their constant work on the stabilisation of the social. To identify this work two conceptual tools are used: standardisation and collective statements. Standardisation refers to the work of institutions, laboratories, organisations and theories, to stabilise the social. The social world is not stable in essence but it is stabilised through the work of standardisation. Social perspectives are standards that help actors to define themselves. So, these standards ‘that define for everyone’s benefit what the social itself is made of might be tenuous, but they are powerful all the same’ (p. 230). However, they are not universal. They are as long as conduits through which the social circulate and connections that keep them alive.

Another conceptual tool that enables ‘the transportation of agencies over great distance’ (p. 221) is called collective statement. It is less formal than a standard, but its circulations have the same effect of stabilising and formatting the social. Latour asks us to consider what is triggered when we use a collective statement such as ‘Axis of Evil’ or call for ‘an Islamic Enlightenment’ in front of a Middle Eastern audience, or ‘what is achieved when an American proudly exclaims “this is a free country!”’ (p. 232). Each time when collective statements are used, they both format the social and provide a theory as to how the social should be formatted. However, collective statements do not represent social structure or context. Rather, they are ‘scripted’ in tiny places such as oligopticons, and actors from time to time ‘subscribe’ to the partial totalisation provided by collective statements. Subscribing means that actors can receive something from the outside, by plugging into instruments of a large institution, which will stay within actors for a while, and then make a way for something else, illuminating differently another instrument and another institution (Latour & Hermant, 1998).

However, this ‘networky’ shape leads to a question: What is it between the conduits that connect the sites through which the social circulates. This vast unconnected space is designated by Latour as plasma: ‘namely that which is not yet formatted, not yet measured, not yet socialized, not yet engaged in metrological chains, and not yet covered, surveyed, mobilized, or subjectified’ (Latour, 2005, p. 244). These empty spaces between networks ‘are the most exciting aspects of ANT because they show the extent of our ignorance and the immense reserve that is open for change’ (Latour, 1999a, p. 19). The metaphors of network and plasma illustrate ANT understanding of space. The outside is not a global context; the network is not placed within layers of structure. The network traces the connected, the outside is simply that which is not yet connected. The outside is not some social force hidden behind but it is rather this unknown place of plasma, which provides ‘the resources for every single course of action to be fulfilled’ (Latour, 2005, p. 244).

Plugging into nationalism and cosmopolitanism

Latour (2004c) points out that he has never considered society as a nation state for two reasons. First, scientific networks, which were frequently the focus of ANT exploration, have never been limited to national territories. Second, and more importantly, in ANT approach ‘society has always meant association and has never been limited to humans’ (p. 451). While many scholars from modernist approaches to nationalism recognise a role of non-human factors in nation building such as print (Anderson, 2006) and technology (Gellner, 1983), these factors are regarded as mere resources, intermediaries that simply transport power, rather than crucial actors in the construction of nation and nationalism. These scholars know very well that ‘popular festivals are necessary to “refresh social ties”; that propaganda is indispensable to “heat up” the passions of “national identities”; that traditions are “invented”’ (Latour, 2005, p. 37). They agree with the ANT positions on identity, space and time, which suggest that national identity is constructed, national territory is a limited space composing different interests, and shared time is a result of invented tradition and imagined future. However, they do not see the crucial importance of the means of construction and reproduction of nationalism, which are rather seen as passive intermediaries.

On the other hand, for an ANT account, ‘it makes a huge difference whether the means to produce the social are taken as intermediaries or as mediators’ (p. 38, emphasis in original). An intermediary simply ‘transports meaning or force without transformation: defining its inputs is enough to define its outputs… [while mediators] transform, translate, distort, and modify the meaning or the elements they are supposed to carry’ (p. 39). It is not enough to recognise that nations and nationalism are constructed, and then to treat the ‘construction tools’ as passive intermediaries, that simply transport a ‘social force’ as a cause of an effect, in order to understand nationalism. If those construction tools are seen as mediators, we can fully appreciate the difference they make. This is a reason why it is important to trace group formation. Nationalism is not maintained by some ‘social inertia’ of ‘national sentiment’, but by the constant work of many mediators to preserve ‘grouping, which is not a building in need of restoration but a movement in need of continuation’ (p. 37). Feeding the uncertainty of group formation enables us to understand a nation ‘as the ongoing construction of a sociotechnical network that is always enrolling and being enrolled’ (Abramson, 1998, p. 16). For ANT, a nation is just one of many possible heterogeneous networks to which individuals could be attached. It is not a cause but an effect of attachments. Or to paraphrase Latour: there is no nation, but only nation formation, that is a nation ‘is not what holds us together, it is what is held together’ (Latour, 1986a, p. 276).

However, students of nationalism were frequently puzzled with apparently special power of people’s emotional attachments to their nation that ‘hold them together’. This might be a reason for the question – why so many millions of people willingly die for such limited imagining – to remain the ‘central problem’ for scholars of nationalism (Anderson, 2006, p. 7). Latour’s (2005) advice is that ‘whenever anyone speaks of a “system”, a “global feature”, a “structure”, a “society”, an “empire”, a “world economy”, an “organization”, the first ANT reflex should be to ask: “In which building? In which bureau? Through which corridor is it accessible?”’ (p. 183). Instead of a priory mobilising agency and structure, an ANT account of nationalism would first ask some simple questions about associations: In which place has this structure been produced? In which office? In which database? How did individuals access it? Through which cables have they downloaded those emotional attachments? For which purpose? To die or to survive?

Latour (2005) claims that as soon as such queries are being raised, the social landscape begins to change from an overarching pyramid of power into the flattened landscape, illuminating fragile associations between heterogeneous actors. Such a flattened landscape illuminates the means of construction and reproduction of nationalism, not as passive intermediaries, but as mediators. This projection keeps the landscape firmly flat by a series of clamps, described in the previous section, which forces nationalism, or ‘any candidate with a more ‘global’ role to sit beside the ‘local’ site it claims to explain, rather than watch it jump on top of it or behind it’ (p. 174). The global is localised, and the local is distributed, moving structures and individuals to the background and connections into the foreground. There is no mysterious social force ‘behind’ the actors to be ‘revealed’. This does not mean that the world of actors has been flattened out, but that the flatness became the researcher’s default position, and that actors ‘have been given enough space to deploy their own contradictory gerunds: scaling, zooming, embedding, ‘panoraming’, individualizing, and so on’ (p. 220). Without this flat projection, it is possible to think that those millions of people willingly die for their nations. It is possible to mistake an instinct that our local world has already been constructed by some other spaces and times with a social explanation that any local interaction is predetermined by some global overarching context such as nationalism.

An ANT projection enables us to understand how different spaces and times are constructed locally ‘inside the networks built to mobilise, cumulate and recombine the world’ (Latour, 1987, p. 228, emphasis in original). To build, extend and maintain these networks is to act at a distance from the ‘centres of calculations’ – the calculations ‘that sometimes make it possible to dominate spatially as well as chronologically the periphery’ (p. 232). In such a projection, nationalism is not seen as a global context in the shape of a panopticon overseeing any action, but as an oligopticon, a tiny local place where the global is produced and calculations are performed, which illuminates the means of construction and reproduction of nationalism in the shape of fragile connections.

The fragility of these connections might explain my bewilderment with the speed of the rise of an extreme nationalism among a large part of the Yugoslav academic community in the late 1980s, described in the introduction. In the matter of a few years, a cosmopolitan country ‘with a tradition of tolerance’ became ‘a land of historical hatred’. In the early 1980s, nationalism in Yugoslavia was just an abstract global concept – a panorama inside the heads of a few marginal intellectuals and politicians, trying to paint a prophetic picture of their ethnic groups. It was thus too global to have any impact. Only when it became localised into a number of oligopticons in specific offices, with specific connections, nationalism could be redistributed. In the beginning of 1990s, it became so local that it was almost impossible to escape its ‘overarching’ power.

A suggestion that millions of people die for their nations is just an instinct that individual actions should not be taken as ‘some primordial autochthony’, but ‘on the contrary, as the terminus point of a great number of agencies swarming toward them’ (Latour, 2005, p. 196). It seems that this instinct leads modernist approaches to nationalism to try to find a compromise between subjectivity and social structure, which merely extends the gap between individuals as free agents and nationalism as a structure. In such a projection individuals and nationalism are ordered on top of one another inside a three-dimensional structure, making any connection between the two invisible. ANT takes seriously this instinct that there is no global place that dominates all other places, nor a local place that is self-contained, and moves its focus from sites and places to connections. Its approach, in which nationalism is localised into specific offices makes visible the means of redistribution of nationalism, providing an empirical traceability between the construction sites of nationalism and individual actions. The construction sites of nationalism, in this projection, ‘look like the intersections of many trails of documents traveling back and forth, but local building sites, too, look like the multiple crossroads toward which templates and formats are circulating’ (p. 204). However, this circulation of documents and inscriptions is not enough to explain attachments to nationalism, as ‘there is still a huge distance between the generic actors preformatted by those movements and the course of action carried out by fully involved individualized participants’ (p. 205, emphasis in original).

In order to understand how a generic actor, swarmed by a number of agencies, becomes a fully involved individualised participant in the action, we have to use another conceptual tool that Latour calls plug-in, ‘which allows actors to interpret the setting in which they are located’ (p. 205). As noted earlier, Latour intentionally borrows the term plug-in from the Web in order to stress that subjectivity, personality, individuality or cognitive ability is distributed. The individual is not ‘a whole’, a subject with a given identity, but the provisional achievement of a layered and composite ‘assemblage of plug-ins coming from completely different loci’ (p. 208). This flattened projection renders a landscape where the outside is not a global context that determines inside, nor is the inside ‘an inner sanctum surrounded by cold social forces like a desert island circled by hungry sharks’ (p. 215). Nationalism does not determine individual action as it has real impact only when it is locally plugged in by individuals, and even then it competes with other plug-ins, all coming from different locations. Individuals could be plugged into a number of different oligopticons, nationalism being just one of these context-building sites. Moreover, individuals could easily attach or detach themselves from these sites at any moment, constantly shifting between different contexts. However, individuals too do not determine their own actions, as they are able to do only what these plug-ins enable them to do, including plugging into other oligopticons. Individuals download plug-ins for specific situations, in order to have a view on the world and to find a place in that world. Without a plug-in, they would be disconnected, they would hopelessly gaze on an empty screen. They plug into nationalism to navigate situations in which they are placed – not to willingly die but to survive.

Latour (2010) illustrates the modernist preoccupation with a discourse of determination and causality with a short comic strip in which a man, comfortably sitting in his armchair and smoking, is approached by his little daughter with a question: What are you doing? When he said ‘I am smoking a cigarette’, the daughter replied ‘Oh, I thought the cigarette was smoking you’, leaving her father in a state of panic, realising that he was being controlled by an object that he held in his hand. This is, for Latour, a typical modernist discourse, constantly jumping from one extreme to another, from an active to a passive form, and vice versa. This little vignette shows a passage from an active form of the subject – ‘a man smoking a cigarette’, fully in control over his action, to a passive form of the subject – ‘a cigarette smoking the man’, in which a cigarette becomes a master and the man is turned into an instrument. The concept of plug-in enables us to bypass this discourse, as plug-ins simply enable someone to do something, rather than determine actions, which is difficult to grasp by modernist discourse, dominated by dichotomies between liberation and alienation, between reactionaries and progressives. While progressives commit an error by believing that detachment is the only road to liberation, on the pretext that any attachment is alienation, reactionaries ‘are categorically mistaken because they believe, on the pretext that detachment is not possible, that one must forever remain within the same attachments’ (p. 56, emphasis in original).

Nationalism is frequently prescribed to the idea of individuals’ ‘natural’ attachments to their nation. Latour (2010) agrees that it is not possible to move from a state of attachment to a state of detachment, but it is possible to add more attachments, or to substitute one attachment for another. Attachments do not determine individual actions. Actions of the individual could only be authorised, allowed, afforded, encouraged, permitted, suggested, influenced, blocked, rendered possible or forbidden (Latour, 2005, p. 72) by nationalism but not determined. Actions will depend on a complex array of other attachments. Thus, liberty is not gained by detachment, as it is defined by some forms of cosmopolitanism, but by adding more attachments that enable subjects to do things. Individuals become cosmopolitans, not by detachment from local places, but by plugging into a local place – an oligopticon that distributes cosmopolitanism. Both nationalism and cosmopolitanism to which individuals are attached are constructed through a local circulation of many mediators.

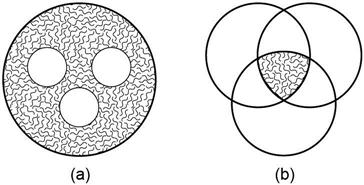

ANT thus offers a completely different projection than existing approaches to nationalism and cosmopolitanism. While these approaches understand a nation/cosmos as a union of its members; in an ANT projection, a nation/cosmos is an intersection (Figure 3.1). The existing approaches to nationalism and cosmopolitanism present a nation/cosmos as something that ‘holds us together’; ANT sees it as something that is ‘held together’. In Figure 3.1a, a nation/cosmos is bigger than its parts as it holds its members together in a union; in ANT projection, ‘the whole is always smaller than its parts’ (Latour, Jensen, Venturini, Grauwin, & Boullier, 2012) since it is seen as something that is held together by different (both humans and non-humans) entities (Figure 3.1b).

While for existing approaches to nationalism and cosmopolitanism, a nation/cosmos is a sum of individuals (Figure 3.1a), ANT does not make difference between an individual and a collective. The intersection in Figure 3.1b can be a nation, a cosmos, an individual or any other entity. For ANT, a nation/cosmos is a network of heterogenous actors including human individuals, but an individual is also a network of heterogenous actors including nations/cosmos. Figure 3.1b illustrates an extremely simplified example of a nation/cosmos, which is a result of intersection of three heterogenous actors, each coming from different time and space. However, an individual can be a result of the same configuration.

It is important to repeat that this is very simplified example and that a nation, a cosmos or an individual is seen as an actor-network, that is an intersection of infinite number of heterogeneous attachments. It is also important to stress that these intersections are merely provisional results, and they can be rapidly changed in shape and size. Within traditional (union) projection, a nation/cosmos/individual is seen as seldom (or never) changed despite frequent replacements of its parts. Such a projection seems convincing as we usually deal with stabile identities in our everyday life. However, we are also often perplexed with abrupt changes that make an individual, a nation, or even entire cosmos unrecognisable. In such events of crisis, it becomes clear that an individual/nation/cosmos is not (and has never been) a union. These cases illuminate constant hard work of holding things together, which is not visible in presentations of cosmos as eternal, nation as timeless and individuals as stable unions. On the other hand, ANT projection allows us to trace both composition and decomposition of unity and identity. It allows us to see why a nation/cosmos/individual has to be constantly reinvented in order to remain the same since any new attachment, detachment, replacement forces the actor-network (intersection) to change its shape and size. In order to keep the intersection the same, the members that form the intersection have to be changed (reinvented), which becomes more visible in the times of crisis.

This is why the concept of cosmopolitics, proposed by Isabelle Stengers (2005), is a useful tool to understand nationalism and cosmopolitanism. The term cosmos in this concept ‘protects against the premature closure of politics, and politics against the premature closure of cosmos’ (Latour, 2004c, p. 454). The term politics suggests that a cosmopolitical proposal is a signed proposal, while the term ‘cosmos refers to the unknown constituted by these multiple, divergent worlds and to the articulations of which they can eventually be capable’ (Stengers, 2005, p. 995). The cosmopolitical proposal, weighted with the feeling that we live in a dangerous world, urges us to think this world differently. It stresses our ‘rather frightening particularity among the people of the world with whom we have to compromise’ (p. 999).

Latour (1997) argues that the concept of cosmopolitics is impossible to understand if we are ‘subscribed’ to the modernist settlement that places nature ‘outside’, mind ‘inside’, politics ‘down there’, and religion ‘up there’, and ‘if the whole settlement is not discussed at once in all its components: ontology, epistemology, ethics, politics, and theology’ (p. xii). Thus, cosmopolitics is a very different project than any modernist or postmodernist project, including modernist approaches to nationalism and contemporary cosmopolitan projects. While they all believe in one nature and one globe already there, cosmopolitics proposes cosmos and the globe as an effect of other processes. The modernist project is based on ‘one nature/many cultures’ divide (Latour, 2002). This combination of mononaturalism and multiculturalism was a political project to bring nature, with its laws, to make an agreement between different cultures, based on an assumption that disagreements ‘between humans, no matter how far they went, remained limited to the representations, ideas and images that diverse cultures could have of a single biophysical nature’ (p. 6). Cosmopolitics, on the other hand, is based on ideas of multinaturalism, where cosmos is constructed as an end product rather than as the starting point of politics. Latour (2004c) points out that common experience in science, art, love and religion indicates that if something is more fabricated, it is more real and more durable (p. 460). Thus, the concepts of ANT and cosmopolitics provide an approach to understand nationalism and cosmopolitanism, as well as information practices, as effects of network building – construction of a common world – in which ontology, epistemology, ethics, politics and theology are composed together.

Information cosmopolitics

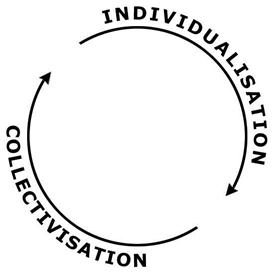

The field of information practices can also benefit from this approach, as it offers an alternative to the user-centred approach by extending agency to non-humans, but also by focusing on relations between entities rather than on entities themselves. A constant shifting and positioning between two main tenets of the field – centrality of the user and the essential role of context in information practices – has become a differentiation point for contemporary IB theories and models, but also the main difficulty in tracing information practices. On the other hand, ANT and cosmopolitics ignore the cognitive/social divide. Instead the information practices are conceptualised as simultaneous and continuous circulation of processes of individualisation and collectivisation. Such a conceptualisation offers a relational approach to information practices, in which information and users, individual and collective, humans and non-humans, cosmos and politics, constantly exchange properties. I use a neologism of information cosmopolitics to describe information practices as the circulation of hybrid entities continuously exchanging properties in the process of composing a collective, which is constantly redefined by the circulation.

In contrast to both cognitive and social approaches in the IB field, and any compromise between the two, information cosmopolitics pays attention to the complexity of the building of a common world as a network of heterogenous materials. For information cosmopolitics ‘there is never much sense in distinguishing the individual and the context, the limited point of view and the unlimited panorama, the perspective and that which is seen to not have perspective’ (Latour & Hermant, 1998, p. 11) as things are not ordered by society or individuals but by associations. Information cosmopolitics becomes visible only when we turn our gaze to traces, inscriptions and circulating references, because the visible is never an isolated image but a movement of images (p. 24).

Following the traces of these inscriptions and focusing on actors’ own competencies to associate ‘place the actors in a position to object, that is, to present their own categorizations’ (Callon, 2006, p. 13). Like the actors they follow, researchers can either ‘remain at their single, particular perspective and limit themselves to an unassignable, invisible, non-existent point or they connect to one of the circuits of paper slips and undergo the most amazing transformation… stretched out, multiplied, scattered, increased, distributed’ (Latour & Hermant, 1998, p. 33). While cognitive structures and social context frequently play an arbitration role in information studies, information cosmopolitics does not need any arbitration work, as cosmopolitics is not a matter of individual or collective ‘good will’, but it is an art ‘disentangled from any reference to some universal human truth it would make manifest’ (Stengers, 2005, p. 1001). It opposes both internal and external approaches to information practices as it proposes that cognition is not internal, nor society is external. For information cosmopolitics, social context is not a container for information users but an effect of users’ own contextualisation, nor is the mind ‘an isolated language-bearer placed in the impossible double bind of having to find absolute truth while it has been cut off from all the connections that would have allowed it to be relatively sure – and not absolutely certain – of its many relations’ (Latour, 1997, p. xiii). The result of information practices is never an absolute certainty, but it might be a provisional closure for initial perplexity, obtained through this slow circular process of exchanging properties between individuals and collective.

The concept of actor-network enables information cosmopolitics to bypass divisions between individual and collective since it is a hybrid configuration, which is ‘simultaneously a point (an individual) and a network (a collective)’ (Callon & Law, 1997, p. 165). When a network is provisionally stabilised, it becomes an entity, a single unit in its simple and coherent shape. It becomes a black box that has successfully translated heterogeneous materials from which it has been constructed. The collective has been individualised. It takes provisionally the shape of individuals, and for a moment acts as an individual actor. On the other hand, when an individual entity translates and mobilises a number of other entities she, he, or it becomes a network, takes the shape of a network, and acts as a network. The distinction between individual and society is not only unnecessary, but it is misleading, because the source of action is not in the ‘social context’ or in the ‘knowing individual’, but it is an effect of arrangement of heterogenous materials. It is an effect of the circulation in which individual and collective constantly exchange properties, which means that action cannot be explained ‘in a reductionist manner, as a firm consequence of any particular previous action’ (p. 179).

Information cosmopolitics provides an alternative approach to information practices that will enable this study to account for the impact of nationalism and cosmopolitanism on information sharing in academic communities. Information practice is always information cosmopolitics – a constant negotiation (thus politics) between heterogeneous (human and nonhuman) actors in the process of composing a common world (a cosmos) – in which individual and collective constantly exchange properties. Thus, information practices are conceptualised as a continuous circulation of processes of individualisation and collectivisation (Figure 3.2).

Such a conceptualisation ignores both society/individual and global/local dichotomy as every single ‘part is as big as the whole, which is as small as any other part’ (Latour & Hermant, 1998, p. 45). The scale is the actors’ achievement. Individuals are neither in control nor out of control. They are rather formatted by others through plug-ins that help them to import temporary competencies for an action. Individuals are thus not different from a collective, that is they are also oligopticons: ‘blind but plugged in, partially intelligent, temporarily competent and locally complete’ (p. 68). Social perspective is a result of standardisation and institutionalisation. Through these processes of producing standards and distributing roles the social is provisionally unified (p. 85). This provisional totality is to what an actor subscribes temporally in order to gain some meaning of the situation.

However, this provisional closure is mistaken by many IB approaches for an overarching context, thus one of the most frequent strategies in tracing information practices is to place information users in this context. Such a form of mapping could be called ‘mapping as unveiling’ as opposed to ‘mapping as attachment’ (Mitew, 2008b). While this form of mapping information practices produces images of totality, where a map represents relations in reference to context (e.g., already existing politics), the second form produces images of the local heterogeneity where autonomy without attachment does not exist, so the map is a result of tracing the relations performing the politics, which is an effect of performativity rather than an a priori context. As such, information cosmopolitics provides an approach to mapping information practices in which users and context are effects of different configurations of attachments and plug-ins through which individual and collective constantly exchange properties. This configuration is the focus of mapping information practices.

Megalomaniacs confuse the map and the territory and think they can dominate all of Paris just because they do, indeed, have all of Paris before their eyes. Paranoiacs confuse the territory and the map and think they are dominated, observed, watched, just because a blind person absent-mindedly looks at some obscure signs in a four-by-eight metre room in a secret place (Latour & Hermant, 1998, p. 28).

Information cosmopolitics shifts its attention to inscriptions through which information and users, individual and collective, humans and non-humans, cosmos and politics constantly exchange properties. Outside is not a general framework or global context, nor is inside an individual mind making sense of the outside. Information is always transformation that never stops in places called ‘Inside’ or ‘Outside’. Thus, it is not possible to ‘reveal’ the external (social) or internal (cognitive) forces behind the individual information practices, but it is possible to map circulation of attachments, through which inside and outside, users and context, are provisionally stabilised. The map of Paris (that megalomaniacs confuse with a territory that they dominate) is just an inscription coming from an institution. The institution (that paranoiacs confuse with a panopticon) is just an oligopticon, which defines the general framework in which individuals can set their own point of view: ‘I hold in my hand what holds me at a distance; my gaze dominates the gaze that dominates me’ (Latour & Hermant, 1998, p. 10). Without inscriptions there is no general framework nor an individual point of view. There is no nationalism without distribution of ‘a national programme’, nor cosmopolitanism without inscription of a cosmos, as there is no religion without a local priest. The concept of information cosmopolitics will enable mapping information practices as tracing continuous circulation of processes of individualisation and collectivisation, by conceptualising information as something that ‘I hold in my hand’ and which simultaneously ‘hold me at a distance’.