Setting up the fieldwork

The underlying methodological principle of this study was to follow the actors in the fieldwork. The field research has been conducted at a university in Bosnia, providing rich data to explore the impact of nationalism and cosmopolitanism on information sharing in academic communities. This chapter describes preparations for the fieldwork, data collection methods employed and Latour’s circulatory system of scientific facts that has been used as a guide to follow the actors at the field.

Keywords

Field research; episodic interviews; observations; following the actors; Latour’s circulatory system of scientific facts

This study draws mostly on qualitative data obtained through various data collection methods including observation, taking field notes and interviews. The field research has been conducted at a university in Bosnia, where both memories of the violent war between three ethnic groups (Croats, Serbs and Bosniaks) and memories of cosmopolitan life in former Yugoslavia were still fresh. In this context, the university has provided rich data to explore the impact of nationalism and cosmopolitanism on information sharing in academic communities. Latour’s (1999b) circulatory system of scientific facts has been used as a guide to follow the actors in this university. This system outlines five activities that researchers simultaneously perform in their everyday work: mobilisation of the world – converting the world (objects of their study) into arguments (discourse) by using instruments, expeditions, surveys, archives, databases and similar; autonomisation – convincing their colleagues within disciplines and institutions in their arguments; making alliances with actors outside of the academic world to support their research; public representation – aligning their research to the everyday practice of the public; and creating their conceptual content – ideas, concepts, propositions, theories, knowledge claims, etc. These five activities shape each other through the process of translation – a process of aligning different interests in a new composite goal. The aim of the fieldwork was to follow these translations. This chapter describes preparations for the fieldwork. The first section describes the research site, data collection methods employed and the limitations of the study. The second section discusses the elements of the Latour’s (1999) circulatory system of scientific facts in relation to information sharing practices in academic communities.

Following the actors in the field

The underlying methodological principle of this study was ‘to follow the actors’. This is the main methodological principle of ANT, which ‘has no unique set of methods with which it is associated, but makes use of many of the same techniques as ethnography and case study’ (Tatnall, 2000, p. 80). The central methodological concern of this study was how to capture the emergence and evolution of information sharing in scholarly communities. Rather than identifying the products of scholarly collaboration such as multi-author papers, the study was focusing on processes by tracing information sharing in making. The expectation was that the most useful research data would emerge in the interaction between actors involved in information sharing. Burgess (1984) suggests that interaction is the focus of field research with the ultimate aim ‘to study situations from the participants’ point of view’ (p. 3). Neuman (2000) claims that field research is appropriate when research objectives involve ‘learning about, understanding, or describing a group of interacting people’ (p. 345). It is particularly useful for the main methodological principle of ANT, which is to ‘follow the actors’.

The complex political structure of post-war BH, where the field research has been conducted, provides no single ministry dealing with education on the state level. The authority over education is given to the two entities: the Federation of BH (FBH) and Republic Srpska (RS). In RS a single ministry of education manages the educational sector, while in FBH, the Federal Ministry of Education has transferred the authority of education to the 10 cantons (OECD, 2001). There are eight universities in BH, with around 60,000 students and about 5000 teaching staff. These universities ‘could be roughly categorised along ethnic lines, [where] Croatian-based universities…consider Croatian curricula and materials a natural choice, while the Republic Srpska looks to the Serbian Republic for curriculum’ (p. 38). The university chosen for this study is placed in the canton dominated by Bosniaks. It was primarily selected for its position in central BH, being between Croat and Serb dominated territories and with a scholarly community still nationally mixed, although Bosniaks were in the majority. However, a significant reason was also the fact that scholarly community was made up of scholars from different academic specialties from medicine and computer science to language and literature studies. The field work has been conducted from April to December 2009, with the following-up interviews conducted from September to October 2011.

Most of the 34 participants were employers of this university. However, scholars from other universities, identified through snow-balling, have participated in the study, so there were also five participants from other Bosnian universities, one researcher from the local cantonal government, two from Croatia, one from Serbia and one participant from Canada. The university had seven faculties: Faculty of Metallurgy and Materials Science, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Education, Faculty of Economics, Faculty of Law, Faculty of Health and Faculty of Islamic Pedagogy. The university also had an institute for metallurgy and several research centres. The university was mostly funded by the local cantonal government, serving a population of about 400,000 people.

In 2009, during the fieldwork, the university had 493 teaching staff, from which 133 were full-time employees. There were 5950 students, including almost 600 postgraduates and 30 doctoral candidates. The participants consisted of 5 professors, 7 associate professors, 4 senior lectures, 13 lecturers, 3 doctoral candidates and 2 master research students. Twenty-one long episodic interviews have been conducted mostly in participants’ offices, although two interviews were conducted in private apartments, and two in a coffee shop. I have also conducted 72 short unstructured interviews that lasted 10–20 min, which have identified a number of instances of information practices. In addition, I have spent an average 3 full-time days a week at the university, attending participants’ lectures and meetings, as well as spending a lot of the spare time with participants in the university coffee shops. I wrote daily the field notes, a diary and ‘media notes’, which involved both participants’ and my reflections on the public academic debates in BH.

Data collection

The study used mostly qualitative data collection methods including observation, taking field notes and interviews. In addition, a short questionnaire has been conducted in order to identify and compare the impact of nationalism on conceptual content, research topics and theoretical claims of scholars from different academic fields. Pouloudi et al. (2004) point out that although ANT scholars provide detailed accounts of how actors form stable actor-networks, they do not provide specific, generic guidance on how we can identify the actors. As the aim of this study was to investigate scholars from a diverse range of academic specialties, maximum variation sampling was used to identify main actors. Patton (1990) argues that this type of purposeful sampling can identify important common patterns across variations. In order to maximise variation a researcher begins with ‘identifying diverse characteristics or criteria for constructing the sample’ (p. 172).

The first step in the identification of potential actors was creating a list of scholars and their specialties drawn up from the university’s website and direct contacts with the university. Next step was the creation of a short list of the main actors. Finally, the actors were followed by using a strategy based on snowball or chain sampling, ‘an approach for locating information-rich key informants or critical cases’ (Patton, 1990, p. 176) by selecting ‘cases from referrals by participants’ (Bailey, 2007, p. 65). Fry (2006) suggests that this technique is particularly useful for tracing actors in an academic specialty field. Browne and Russell (2003) point out that although this approach can be useful to explore cases that require insiders’ knowledge, it is often limited to a homogenous sample since ‘a chain of connection between participants … can exclude diversity’ (p. 78). However, a combination of this technique with the maximum variation sampling has provided both diverse and information-rich samples.

The main research method was narrative interviewing. Stories captured in narrative interviews are not simply reflections of the objective world, but they are constructed, rhetorical and interpretive (Riessman, 2004). Thus, stories obtained in the field can be used to trace activities of actors in networks and to capture participants’ interpretations of how they make sense of their environment. The participants are encouraged to relate stories to their subjective judgment of what is relevant, without being influenced by interviewers’ questions. Hence, the researcher’s task is ‘to follow the actors’. McCormack and Milne (2003, p. 5) point out that narrative interviews allow participants to explore issues in a way that feels comfortable for them, and interviewers are rather active listeners who merely support storytelling by seeking clarifications and explanations.

Wagner and Wodak (2006) point out that the main idea of a narrative interview is to encourage participants to tell stories and that a good narrative interview ‘allows for a certain amount of reflection, supporting a person in remembering, making connections, evaluating, regretting or rejoicing’ (p. 392). According to Riessman (2004), the challenge for narrative research is to avoid data reduction, since traditional interview techniques often edit out the context of the narrative text. In order to avoid editing out the context of participants’ information practices, this study has adopted a particular narrative interview technique – episodic interviewing (Flick, 1997), ‘which is sensitive for concrete situational context’ (p. 2).

Episodic interviewing

This method is based on theoretical assumptions that narratives are constructed experience rather than experience per se, and that there are two kinds of knowledge: semantic and episodic. While semantic knowledge is rather abstract, generalised and decontextualised, the episodic knowledge is linked to situational context such as time, space, person, event and situations. Flick (1997) outlines three main criteria to access both semantic and episodic knowledge. First, the interview should combine invitations to recount specific events with more general questions. Second, the interview should invite the specific situations of participants’ experience. Finally, the interview should be open enough to allow participants to select episodes that they found relevant for the agenda. Bates (2004) argues that Flick’s episodic interviewing techniques are particularly useful for studies of everyday life information-seeking behaviour, where participants can ‘describe in their own words their information needs and information-seeking experience’ (p. 16). To let actors to speak their stories in their own language, this study used Flick’s (1997) stages in the interview process including:

• preparation of the interview;

• introducing the interview principle;

• the interviewee’s concept of the issue and his/her biography in relation to the issue;

• the meaning of the issue for the interviewee’s everyday life;

• focusing on the central part of the issue under study;

During the first stage of preparation for the interview, the interview guide has been developed from the theoretical accounts gained by literature review. The guide was designed to be open to accommodate any emergent issues that can be introduced by participants. The documentation sheet was also designed to cover the information relevant for the research question.

The interviews started with the instruction of the interview principles to the participants, where care was taken to help participants to understand the aim and the method of the interview. The interviews were always introduced by a slight improvisation of the following statement:

During this interview, I will ask you to describe situations where you were involved in information sharing within your local (the University), national (Bosnia), and international scholarly communities. I would like you to tell me the ‘story’ of your relationship with other scholars – the events, people and processes that have shaped this relationship. I would like to hear about events like: discussions with colleagues about the issues of your interest; reading a work by other authors that affected your view on a topic of your academic interest; attending a conference or seminar where this topic was discussed; and how information sharing helped your own research.

Then the interviewee’s concept of the issue and his/her biography in relation to the issue was explored. Participants are firstly asked for subjective definition of the study’s issue in order to start the topic. Then, the participants’ account of information sharing and their first encounters with academic collaboration were discussed. Questions used for this aim included:

What is related to the word ‘information sharing’ for you? When you look back, what was your first experience with scholarly information sharing? Could you please tell me about this situation?

The aim of such questions was to encourage participants to remember a specific episode and to recount it in their own words, which is the main principle of an episodic interview. The situation that participants select was left for them to choose and it was not predetermined by the interviewer. The aim was to capture participants’ personal history related to information sharing. The participants were encouraged to recount these situations by questions related to their specific and meaningful experiences with information sharing. The intention was to get the story from the participants’ point of view and the interviewer’s intervention was kept to a minimum.

However, there were some situations where participants needed help to refocus. It was important to pay attention to any point and ask additional questions to bring more depth into the interview. Then, the interviewer helped with questions such as:

There are some situations where we find that information sharing has particularly helped us. Can you please tell me about a situation where you found that you were particularly helped by information sharing with other scholars? Sometimes we feel that we are worse off because we are unable to get some information we need. Can you remember any situation where you feel you needed some academic information but you were unable to get it? Could you please tell me about the situation?

In order to identify the meaning of the issue for the participants’ everyday life, the participants were asked to recount a typical working day with reference to scholarly information sharing. One of the questions they were asked was: Could you please recount one day in the last week where information sharing played a part in it? This question aimed to provoke narratives of a series of relevant situations, which could in turn create new questions producing new narratives. Then they were asked various questions about domains in their everyday life, which aimed to help the participants to reflect on the meaning and relevance of scholarly information sharing for their everyday life in different aspects, such as: Who in your scholarly community takes care of information sharing? Please tell me about a situation typical for that!

Next stage of the interview focused on the central issue of the study. The questions designed for this stage had the function of provoking participants’ narratives and the challenge for the interviewer was ‘to respond with deepening enquiries to the interviewee’s answers and narratives in order to make the interview as substantial and deep as possible’ (Flick, 1997, p. 10). The intention was to get into as much details as possible. Some of these questions included:

What do you link to the word ‘nationalism’? Which practices do you link to nationalism? Did you ever feel that you were excluded because of nationalism? Please recount a typical situation for that! What are some alternatives to ‘nationalism’? Which practices do you link to these alternatives? What is the role of nationalism or an alternative to nationalism in your everyday academic life? Could you please tell me about a situation of that kind? Does the Internet help information sharing between scholars coming from different national units in Bosnia? Can you please give me an example of this?

Then the interview dealt with more general topics referring to the issue under study. In this stage, the participants were asked for more abstract relations, in order to enlarge the scope of the discussion. This part of the interview aims at elaborating the interviewee’s cross-situational knowledge they had developed over time. The questions included:

Do you think that emergence of global communication technologies such as the Internet is challenging nation-states? What do scholars do in situations when they have to choose between their loyalty to the academic community and the loyalty to their nations? Some authors claim that national culture is one of the main factors that can act as a barrier to information sharing. Do you think that national culture of different nations in BH is a barrier to information sharing between Bosnian scholars? What is the role of academic field in information sharing between scholars coming from different national units in BH? Can you please give me an example for that?

The final part of the interview was evaluation of the interview by the participants with questions such as: What was missing in the interview to mention your point of view? Was there anything bothering for you during the interview? It was useful to take time for small talk, during which participants talked about relevant topics in a more relaxed manner, outside the formal interview framework. A context protocol has been written immediately after each interview. The prepared sheet included information about the participants and about the interview (when, how long, who was the interviewer, etc.). The sheet also included a space for the interviewer’s impressions of the situation and the context of the interview and participants. Everything important that was said after the tape recording stopped has been noted with participants’ permission.

Field notes

However, as the individual accounts obtained by interviews were insufficient to track all aspects of information sharing, participant observation was also an important method in collecting the data. By using this method, researchers can ‘open the way for a more sophisticated analysis than is possible with experimental and questionnaire- or interview-based survey research alone’ (Sandstrom & Sandstrom, 1995, p. 191). Such an unstructured moderate participant observation was an important method to ‘follow the actors’. I spent on average 3 full days a week at the university during the field research. This relatively active participation enabled me to observe the participants’ behaviours and interactions in different contexts. The participants were observed in their everyday academic activities during the lectures and meetings, but also in their casual conversations in the university coffee shops. All observations took place at the university lecture theatres, offices and coffee shops, during normal working hours.

Latour (2005) advises that field notes should be taken ‘to keep track of all our moves, even those that deal with the very production of the account…because from now on everything is data’ (p. 133, emphasis in original). The organisation of the field notes was based on Chatman’s (1992) note taking method that ‘involves observational notes (simply reporting phenomena), method notes (strategies employed or that might be employed to obtain data) and theory notes (involving the testing of construct validity and the generation of propositional statements to explain phenomena’ (p. 15). In order to capture the public representation of scholarly activities ‘media notes’ were also kept. This involved both participants’ and researcher’s reflections on the public academic debates in BH, and these notes were an important source for a number of narrative episodes, described in the next chapter. The news and public debates have been selected by participants and then followed through major Bosnian media. This usually involved simply recording participants’ reflections and the main plot of the debate, but in some cases semi-structured and unstructured interviews were conducted in order to clarify an issue. Such separation allowed ‘multiple meanings to arise upon rereading direct observation notes’ (Neuman, 2000, p. 365). In addition, a personal diary was kept since researcher’s personal issues ‘might color what he or she observed’ (p. 366).

Questionnaire

A short questionnaire has been conducted at the university to investigate the impact of nationalism on the conceptual content in the work of scholars in different disciplines. The questionnaire was based on Fry and Talja’s (2004) propositions that academic specialty fields with a high degree of mutual dependence and low degree of task uncertainty have a stable research object and field boundaries; while within fields with low degree of mutual dependence and high degree of task uncertainty, research objects, research techniques and significance criteria are minimally coordinated. This suggests that information practices within the first group are highly coordinated and conformity to communicative norms is high, while within the second group, research problems can be approached from diverse perspectives, and the results of diverse studies are not necessary comparable.

The questionnaire has involved scholars from the two groups of academic specialty fields. One group consisted of 19 scholars from the specialty fields with high degree of mutual dependence and low degree of task uncertainty such as fields in medical science, mechanical engineering, chemistry and computer science. Another group consisted of 14 scholars from the specialty fields with low degree of mutual dependence and high level of task uncertainty such as national literature, history and communication. The questionnaire was designed to obtain answers on how nationalism influenced scholars’ activities such as accessing data, collaborating with their academic community, obtaining research funding, participating in the public life and how all these activities have influenced the conceptual content of their research.

Data validation

In order to validate the data, some principles of member validation in qualitative analysis introduced by Bygstad and Munkvold (2007) were used. They point out that while in positivist research the main objective of the validation is to verify factual information, the member validation in an interpretive research is a part of the interaction between researcher and participants. Participants, seen as more than just informants, and the researcher construct a common understanding of the phenomenon under study. So, while triangulation may be more helpful for verifying facts, the member validation is focused on verifying that participants’ constructions are understood by researchers.

Bygstad and Munkvold (2007) offer a framework for member validation that follows the three main steps in ‘the ladder of analytical abstraction’. The steps are as follows: summarising interviews and technical document; identifying themes and trends; and identifying patterns and explanation. During the first step, at the lowest level of abstraction, the member validation not only helps to verify facts but can also give important input of data collection. During the fieldwork, this process was frequently identifying new actors. At the medium level of abstraction, the researcher introduces his or her own terminology in participants’ narratives. It is important at this stage to negotiate with participants that their stories are not lost in the researcher’s interpretations. At the third level, the focus is on the implications of the study. Bygstad and Munkvold (2007) suggest that it is important to reach agreement with participants regarding findings of the study since it is unreasonable to disqualify participants’ interpretations, if we accept that participants are co-constructors of the case study. This is even more relevant, if we accept the main methodological principle of ANT ‘to follow the actors’.

In the first stage of data collection I was able to verify factual information, which hopefully increased internal validity of the study. During the construction of the case study stories, I have verified with participants that my construction was a correct interpretation of their stories. Data validation was particularly useful for the creation of a model of information practices, described in Chapter 6.

Study limitations

A major study limitation is that it draws on a relatively small sample of scholars from a university and a country that could not be presented as a typical setting, so the generalisability of the results could be doubted. The memories of violent nationalism during the Balkan wars in 1990s were still fresh at the university, which could influence the participants’ responses. The relatively small number of participants was justified by the nature of a qualitative research to rely on rich data, so the focus was on exploring processes involved in the interplay between information practices and nationalism rather than on statistical significance. Nevertheless, in order to address this limitation, a combination of different sampling techniques was used to produce both diverse and information-rich samples. This sampling strategy was also used to address a difficulty inherent to ANT main methodological prescription to follow the actors. Some ANT studies (Pouloudi et al., 2004) reported difficulties in selecting the actors to be followed. A version of snowball sampling is often used to follow the actor, but the main limitation of this technique is a tendency to produce a homogeneous sample. In order to address this limitation, the maximum variation sampling was used to identify main actors even before the field research commenced.

Another limitation of the study is related to the interpretation of some data. The participants’ definition of information practices in Chapter 6, on which the final model was built, was partly based on very short interviews (10–20 min). Furthermore, although the member checking has been conducted in order to validate the data and confirm my translation of these practices in IB language, this negotiation between my and participants’ definitions could be biased. Some participants explicitly expressed that they regarded me as an IB expert, so there was a possibility that the results of the negotiations were sometimes formed on this basis. There were also some difficulties with the implementation of participant observation method. It was initially difficult to avoid ‘reactivity’ (Bernard, 1994), a tendency of participants to act in a certain way when they are aware of being observed. It was more difficult to enrol ‘nationalists’ than ‘cosmopolitans’ to participate, perhaps because they felt uncomfortable being observed. Hence, I needed more time to build trust with nationalists. Finally, the obvious focus of the field study on Bosniak nationalism in a country with three major ethnic groups (Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats) might be seen as a limitation of the study. However, my decision to focus more on nationalism of ‘my own’ ethnic group was an effort to avoid a possible bias toward ‘others’.

Following the actors: Latour’s circulatory system

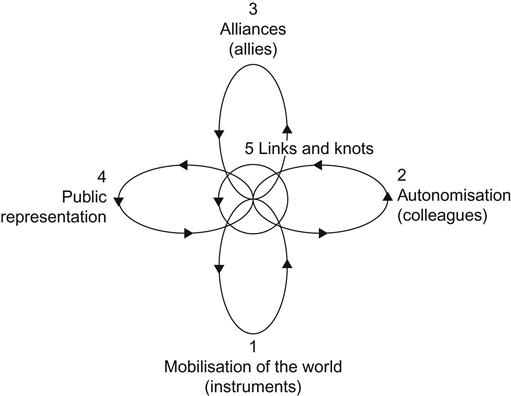

Latour’s (1999b) circulatory system of scientific facts (Figure 4.1) has been used, in this study, as a guide ‘to follow the actors’ in the field. This system outlines five different activities ‘that all researchers will hold simultaneously if they want to be good scientists’ (p. 99). Researchers have to simultaneously get their instruments to work, convince their colleagues, interest possible alliances, give the public a positive image of their work and deal with the conceptual content of their research. These activities are represented as five interactive loops: mobilisation of the world, autonomisation, alliances, public representation, and links and knots. If we are to understand the work of researchers, each of these loops should be described, since each ‘is as important as the others, and each feeds back into itself and into the other four’ (p. 99). It is important to stress that ANT rejects divisions between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ sciences as it rejects divisions between human and non-human actors (Latour, 2005, p. 125); therefore, this system includes all actors involved in research activities within the social sciences, humanities, arts or natural sciences (Latour, 1999b, pp. 18–20).

This section discusses the components of Latour’s system, applied to academic information sharing practices as illustration. The system emphasises the interdependent relationship between contextual elements and information practices, which is what distinguish it from existing IB models. Context is not presented merely as a background for information practices, but at the same time, information practices are not seen simply as a construction of social or cognitive context. Accordingly, instead of a priori placing actors in a context or defining their identities with a cognitive style, the proposition of this system is to follow the actors, creating themselves context and identity. As such, this system provided a more effective means to understand information sharing practices from the actors’ point of view. The main elements of the system and the relations of each loop to information sharing practices in academic communities are described below.

Mobilisation of the world

The first loop in the system is called mobilisation of the world. It refers to the ‘means by which nonhumans are progressively loaded into discourse’ (Latour, 1999b, p. 99). These means include not only instruments, equipment, expeditions and surveys but also the sites in which the mobilised objects are assembled and contained such as museums, libraries, and databases. By mobilising the world, scientists transform the world into immutable and combinable mobiles, which means that ‘instead of moving around the objects, scientists make the objects move around them’ (p. 101). These objects, inscribed ‘into a sign, an archive, a document, a piece of paper, a trace’ (p. 306), are mobile but they are also immutable ‘because the objects hold their shape as a network’ (Law, 2002, p. 93).

Mobilisation of the world enables things to ‘present themselves in a form that renders them immediately useful in the arguments that scientists have with their colleagues’ (Latour, 1999b, pp. 101–102). This is a major way for actors in information sharing academic communities to gain authority. Obtaining data is seen as an achievement, because data ‘contrary to their Latin name, are never given; they are obtained’ (Latour & Hermant, 1998, p. 22). For Latour, a word does not simply refer to a thing, but it is progressively loaded with meaning through progressive chains of translations (Latour, 1999b, p. 99). The study of mobilisation of the world ‘is the study of the logistics that are so indispensable to the logics of science’ (p. 102, emphasis in original). To study the logistics of information sharing practices in academic communities involves not only the study of instruments for obtaining data but also the study of information sources and places used to keep and share these resources (libraries, databases, and information and communication technologies).

Access to resources and instruments may be indicative of the status of researchers in the field. If their research is based on powerful instruments, researchers can be regarded as a ‘gatekeeper of the field’. Katz and Martin (1997) point out that the reason for a high degree of collaboration in research that involves large or complex instruments is not only because of economic benefits but also ‘the need for a formal division of labor’ (p. 4). The degree of information sharing in academic communities is proportional to the speed of the circulation of all loops in the circulatory system. In an ideal situation, academics will share not only data but also ideas, instruments, equipment and laboratories, where appropriate. In such a situation, this loop will be a major trigger for the circulation of all other loops. In an opposite situation, there will be nothing to share, the circulation will stop and the whole system will collapse.

In most cases, academics do not share all of their data, selecting only certain information to be shared. The reasons for this kind of behaviour might be a result of the circulation in other loops in the model. For example, Velho (1996) shows how researchers from some countries see the removal of biological species from Brazilian Amazonia as a normal scientific activity, while many local Brazilian scientists see this activity as economic and scientific imperialism. Avoiding information sharing can be a result of negotiation within the alliances loop. The reason may also be the researchers’ attempts to gain a reputation among colleagues by being the only ‘spokesperson’ for the mobilised objects, the only actor to have the roadmap of the chains of translations that transform these objects to information.

Willingness to share information therefore depends on negotiations with other actors such as colleagues, allies and the public – the circulations of the other loops – rather than on any cognitive style, or ‘internal’ and ‘external’ non-negotiable forces. In order to understand the circulation of this loop, it is therefore not enough to understand the achievement of obtaining data and building powerful instruments alone. It is also important to understand negotiations that enable the circulations of other loops through this loop. Whenever we ask how data is obtained, we have to follow with questions such as: How is this related to people’s everyday activities? How will allies respond? How is it credible to colleagues?

Autonomisation

The second loop is called autonomisation since it refers to ‘the way in which a discipline, a profession, a clique, or an ‘invisible college’ becomes independent and forms its own criteria of evaluation and relevance’ (Latour, 1999b, p. 102). This loop deals with the ways that disciplines and institutions provide credibility to the world mobilised in the first loop. Latour argues that an isolated specialist is a contradiction in terms because agreed criteria of relevance, negotiated within these associations of specialists, and regulations of scientific institutions are ‘necessary for the resolution of controversies as is the regular flow of data obtained in the first loop’ (p. 103). While this loop directly accelerates the circulations in the first loop by demanding more and more data, it also accelerates the circulation in other loops by increasing the credibility of data. This is why a conflict within this loop ‘is not a brake on the development of science, but one of its motors’ (p. 102).

If for no other reason but to increase the credibility of an argument, obtained in the first loop through the mobilisation of the world, researchers will participate in information sharing activities with their colleagues. An obvious example might be the heavy reliance on peer review employed across the academy. The drive to establish credibility of information is one of the most powerful accelerators of the circulatory system. It is frequently the primary trigger for information sharing practices in academic communities, and it forms ‘the seeds of all relationships among researchers’ (p. 103). Two concepts from the IB field are particularly relevant for this loop: cognitive authority and domain.

Patrick Wilson (1983) introduces the concept of cognitive authority, which is different from administrative authority, to explain the kind of authority that influences the formation of knowledge. Such a cognitive authority may take different degrees since ‘one can have a little of it or a lot’ (p. 14). It is relative to a domain of interest, so a person can be an authority in one domain but have no authority at all in other domains. Thus one ‘might be an authority for many people but in different degrees or in different spheres’ (p. 14). Wilson claims that an individual cannot produce knowledge. She or he can only make proposals to the group ‘and if the proposal is accepted by the group as settling some question for the time being, then a crucial step toward a contribution of knowledge has been made’ (p. 48). Cognitive authority is not limited to humans, but it can be the property of non-humans as ‘we recognize it as well in books, instruments, organizations, and institutions’ (p. 81).

In IB field, the term domain is mostly related to the domain analysis approach developed by Hjorland and Albrechtsen (1995). However, Talja (2005) suggests that using domain as a focus of the study is not a new approach and that authors such as Herbert Menzel and William Paisley were exploring scholars’ information practices within the disciplinary differences already in 1960s. Menzel’s (1958) studies on planned and unplanned scientific communication show that much important information comes accidentally through the scholars’ informal information network, so Bates (1971) considers Menzel as the original, champion of the idea that informal communication is a crucial part of a scientist’s information network.

There are differences between academic groups that can increase the need for multidisciplinary collaboration (Katz & Martin, 1997), however these differences can also hinder or even prevent collaboration taking place (Sonnenwald, 2007, pp. 653–654). For instance, different disciplines have different methods, terminology and different ways of communication. All these issues of building relevance criteria in academic groups and institutions are directly related to the autonomisation loop. But to fully understand how this loop enables or prevents information sharing in academic communities, we have to understand how it is linked to the other loops. How do these academic communities build their laboratories, obtain their data and use their instruments? How do they build a positive public image of their research? How do they enrol powerful allies in order to enlarge their network?

Alliances

The third loop, called alliances, deals with making actors outside scientific laboratories interested in the research. Without this loop, the world could not be mobilised as the instruments could not be developed nor could a discipline become autonomous. For any research development, it is crucial to cultivate interested powerful groups and institutions, such as military, government and industry. The links between these groups and research have to be created since there is no natural and self-evident connection between, for example, the military and physics, industry and chemistry, or kings and cartography (Latour, 1999b, p. 103). However, Latour argues that the aim of investigating these networking activities is not simply to understand the impact of economy on scientific work, but also to understand ‘our own societies: the history of how new nonhumans have become entangled in the existence of millions of new humans’ (p. 104). The aim is not merely to investigate the impact of research funding on research productivity, but rather to understand how different alliances create different research objects.

Alliances are never given. They have to be created, which involves ‘enormous labor of persuasion and liaison…to make these alliances appear, in retrospect, inevitable’ (p. 104). Creating alliances is not a linear process going from basic to applied research. Howells, Nedeva and Georghiou (1998) point out in their UK survey on industry-academic collaboration that although since the 1970s the significance of linkages between industry and academic communities has become fully recognised, these linkages go back a long way, to the late nineteenth century with the establishment of the so-called redbrick universities in the industrial areas of Britain (p. 12). The aim of these universities was to serve academic communities and align these communities to local industry and economy. During the last decade, for example, we have seen a number of alliances built by academic communities interested in developing clean energy. Developing clean energy is becoming a major issue in winning elections in many countries around the world. Unlikely actors, such as car or coal industry, are building alliances with academic communities. These alliances appear more and more inevitable as academic communities translate their interests and the interests of industry into a composite goal. By shifting their interests, both industry and academic communities are not only creating a new goal but also they are building a new context. So, the context is created by actors themselves through a chain of translations. If we place a priori this collaboration in an external context, e.g. capitalism, and/or in an internal context, such as ‘anomalous state of knowledge’ (Belkin, 2005), we will not be able to understand this hard work of building alliances. Instead, we should follow the actors themselves in their context-building activities.

This alliance loop is therefore not concerned solely with research funding obtained through the alignment of interests between powerful actors and academic communities. More importantly, it enables us to understand the socialisation of technology. Perhaps like no other loop, it illuminates the process of swapping properties between humans and non-humans, in which social relations are transformed ‘through fresh and unexpected sources of action’ (Latour, 1999b, p. 197). However, to fully understand the impact of this socialisation of non-humans on information sharing in academic communities, it is not enough to understand only the circulation between this loop and the loop of autonomisation. It is also necessary to understand how it effects the mobilisation of the world. How do these processes change people’s everyday life? What is the public opinion of these processes?

Public representation

The fourth loop, public representation, describes the effects of scientific works on people’s everyday practice. Since science modifies associations between people and things, this loop is no more outside scientific work than other loops in the circulatory system, but rather ‘it simply has other properties’ (Latour, 1999b, p. 105). Public arguments for or against a research practice can have a direct impact on the funding of a particular project. For example, some governments are reluctant to fund human embryo research projects due to public concerns. This reluctance might change the dynamic of other loops, and may even stop the circulatory system as a whole. The relationship between scientists and the public has also the potential to create ‘a lot of the presuppositions of scientists themselves about their objects of study’ (p. 106), which may change the way they mobilise the world, enrol themselves in a discipline or create an alliance.

Public representation loop deals with relations of scientific ideas with ‘people’s everyday practice… [and their] system of beliefs and opinions’ (p. 105). The loop helps us to understand the ways society creates representations of academic work, and the ways that these representations influence information sharing in academic communities. Since academic communities need support from society, they often try to convince society of the benefits of their work through their representatives with a status of ‘acknowledgeable leaders’ (Beaver & Rosen, 1978, p. 67). As the creation of alliances is often largely dependent on public image, academics also try to create a positive image of their research. However, academic communities are also in a danger of losing public reputation due to unethical conduct of the research.

Public representation also has an impact on government allocation of public research funding that encourages business and industry to enrol and invest in academic communities and their research. Public concerns about national security can also encourage governments to place restrictions on publishing and sharing ‘sensitive’ information. However, public representation is not linked only to building alliances. Public concerns can also define the object of academic activities. Finding solutions for public concerns is frequently a major motive for activities of academic communities. For example, the global threat by severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) motivated collaboration among scientists around the world and resulted in finding causes of the disease in only 5 weeks (Sonnenwald, 2007, p. 650). Thus, public representation can be both an enabler and a barrier to information sharing in academic communities.

Public representation changes with changes in a political or cultural environment. For example, Traweek (1995) notes problems in collaboration between Japanese and American high-energy physicists due to cultural differences. By drawing on the concept of small world (Chatman, 2000), Jaeger and Burnett (2005) analysed the impact of US policies on shaping information behaviour in the United States since September 11, and found that these policies ‘have altered the roles of information in many social contexts, with impacts on information access and information exchange between social groups’ (p. 464). Olsson’s (2003) research indicates that this concept can be also applied to academic communities. The concept of small world may help us to understand how the circulation of public representation can both enable and prevent information sharing in academic communities.

All these political, cultural or social contextual elements, described above, circulate through the public representation loop. However, they are not enough to fully understand information sharing practices in academic communities. The public representation loop is only a part of the model. While it has a great impact on the circulation of the model, it is also an effect of the circulation. So, it is crucial to understand how this loop is connected to the other three contextual loops, and how they are all linked to and by the central loop of the model: How they are moved by, and how they are moving this loop of links and knots.

Links and knots

Latour (1999b) calls the fifth loop links and knots in order to avoid the historical baggage of the term ‘conceptual content’. He describes this central loop not as ‘a pit inside the soft flesh of a peach…[but as]…a very tight knot at the center of a net’ (p. 106). The metaphorical difference is not trivial as the main proposition of this model is that scientific work could not be understood if we separate content from context, in the same way that we cannot understand the work of circulatory system of the human body if we separate the heart from the blood vessels. When the model indicates the centrality of the conceptual content, it indicates the significance of understanding for what periphery this loop plays the centre. A concept is not scientific ‘because it is farther removed from the rest of what it holds, but because it is more intensely connected to a much larger repertoire of resources’ (p. 108). This loop keeps all other loops together, and without it the other loops would die, but this would happen ‘just as quickly if any of the other four loops were cut off’ (p. 107).

The loop of links and knots thus deals with scholars’ conceptual content, research topics, theoretical claims, etc. Typically, studies in scholarly communication identify their units for analysis as a discipline or they use disciplinary groupings in physical sciences, health sciences, applied technologies, social sciences and humanities (Fry & Talja, 2004). Case (2002) notes that there is a tendency in IB research to generalise disciplines into science, social science, and the humanities, placing social scientists between other two groups in terms of their information habits. Some authors, such as Becher (1987), classify scholarly disciplines on hard (e.g. physics) and soft (e.g. history) disciplines. Fry and Talja (2004) argue that all these taxonomies show the limitations of broad disciplinary groupings. While they can provide a broad picture of disciplinary differences, they tend to produce ‘idiosyncratic results that do not adequately reflect epistemological activities within the knowledge producing communities that they attempt to represent’ (p. 21). They show that using such a rigid taxonomy can over-generalise those differences. For example, by using Becher’s (1987) taxonomy, the discipline of geography would be identified as a hard discipline. However, if we consider specialty fields within the discipline of geography, we could place some of these fields, such as human, social, or cultural geography, within a soft discipline.

For this reason, Fry and Talja (2004) propose specialty fields as a unit for analysis. They use Whitley’s (2000) model of intellectual and social organisation of the sciences to understand information practices within different fields, which replaces academic discipline as a basic unit for analysis with ‘intellectual field’. The model classifies intellectual fields along the axes of ‘mutual dependence’ and ‘task uncertainty’. Mutual dependence refers to the level of dependence of a field on other fields and other scholars. Task uncertainty is defined as the degree of research result and processes being predictable. In the fields with a high level of task uncertainty research results are frequently ambiguous and subject to conflicting interpretations, while in the fields with low level of task uncertainty, research results are more predictable with less conflicting interpretations.

Fry and Talja (2004) use Whitley’s model in the context of information practices by comparing fields with opposing identities: one with a high degree of mutual dependence and low degree of task uncertainty, and another with low degree of mutual dependence and high degree of task uncertainty. They argue that this model ‘enables us to understand why “topic” and “systematic literature review” are entirely different concepts in different fields’ (p. 27). Their proposition is that fields from the first group have a stable research object and field boundaries. Information practices within these fields are highly coordinated and conformity to communicative norms is high. On the other hand, in the fields from the second group, research objects, research techniques and significance criteria are minimally coordinated. Within these fields research problems can be approached from diverse perspectives, and the results of diverse studies are not necessarily comparable. Based on these propositions, for this study, a short questionnaire has been conducted at the university to compare the impact of nationalism on scholars access to data and instruments (mobilisation of the world), academic community (autonomisation), research funding (alliances) and public life (public representation), and how the circulation of all these loops has influenced the loop of links and knots.

Tracing the circulation

Therefore, the circulatory system suggests that information practices in research communities are shaped by five activities that researchers simultaneously perform in their everyday work: creating their research content (ideas, concepts, theories, knowledge claims); converting the world (objects of their study) into arguments (discourse) by using instruments, expeditions, surveys, archives, databases and similar; convincing their colleagues within disciplines and institutions in their arguments; making alliances with actors outside of the academic world to support their research; and aligning their research to the everyday practice of the public. These five activities shape each other through the process of translation – a process of aligning different interests in a new composite goal. Whenever information circulates from one to another element of the model, it is modified and translated by these elements. This dynamic relationship between loops is the main reason for the non-linear nature of information practices (Tabak & Willson, 2012). Thus, to understand the actors’ information practices is to mobilise their world and follow them in processes of translation while they are passing ‘from one register to another’ (Latour, 1999b, p. 88).

In order to mobilise the actors’ world, the sociology of associations provides the conceptual tools such as oligopticons, panoramas, localisers, plug-ins, standards, collective statements and plasma. Latour (2005) advises that whenever someone speaks of some mysterious structure such as national culture, acting ‘surreptitiously behind the actor’s back’ (p. 175), we should identify oligopticons, by asking: where has this culture been manufactured – in which places and institutions? Whenever actors try to frame their interactions into some context such as globalism, cosmopolitanism, nationalism or multiculturalism, we should find how this context is gathered. Particular attention should be paid to performance and mediation of many non-human actors such as research instruments, computer programs and other objects that localise and format the interactions between researchers. The concept of plug-in could identify the ways in which different institutions, the public, and alliances are connected to the conceptual content of research – how the researchers are individualised by being temporarily plugged into different elements of the circulatory system. In order to understand the construction of identities in research communities, we should follow processes of standardisation. Collective statements that circulate through collaborative networks of research communities in this study should make visible instruments and institutions to which actors are attached. Finally, the concept of plasma could be used to understand enrolment of new ideas to the research networks.

The complexity of the links between the different elements of the circulatory system provides a possibility to start from any loop; however, it is important to remember that we have to allow circulation through all loops in order to understand information sharing practices in academic communities. For example, we can attempt to study how culture impacts on information sharing in different academic fields. In this case we would start from the public representation loop aiming to reach the autonomisation loop through the loop of links and knots. However, as the system does not allow direct access from one loop to another without circulation through all loops, we will also have to investigate alliances and mobilisation of the world. To understand the interplay between nationalism and information practices in research communities we need to follow all those connections through which the translation circulates. The combination of Latour’s (1999b) circulatory system and his conceptual tools for flattening the social (Latour, 2005) has provided many narrative episodes about this interplay. The next chapter presents these narrative episodes.