Spain in Free Fall

Since 2008, considerable uncertainty has arisen regarding the state of the Spanish financial system and the health of Spanish public finances. Having obtained some euro 40 billion ($52 billion) out of a pledged euro 100 billion to beef up the treasuries of its badly wounded banks, Spain is hesitating to apply for support from the ESM, and therefore from ECB’s OMT program.

The Spanish economy is about twice the size of Greece’s, Ireland’s, and Portugal’s put together. The ECB’s OMT rescue program would put a large dent in ESM’s coffers. Theoretically, the common currency area has enough resources to finance a Spanish bailout, but the failure of the Greek rescue saw Euroland’s ability to influence economic policy weakened.

Financial analysts are highly doubtful about Spain’s de facto subordination to European Union guidelines. Neither is it sure whether a banking union would come if and when a fiscal union is established; effective banking supervision by the ECB would be operational by 2014, and Euroland’s fiscal union will hold or fall apart over the next few years.

Keywords

Spain in free fall; debt’s danger zone; internal devaluation; battling against austerity; Spanish banks; Euroland’s taxpayers; “bad banks”; wanting fiscal policy

7.1 Spain Is in the Danger Zone

A look at Euroland shows that the debt crisis, particularly in the so-called “peripheral states,” or “Club Med,” is anything but solved. All of them, including France, are in recession, an additional obstacle to easing austerity measures and for stabilizing their mounting debt. The ECB may be trying to put up firewalls around Spain1 and Italy (for whom it designed OMT) to prevent further escalation of the crisis along the Greek scenario, but:

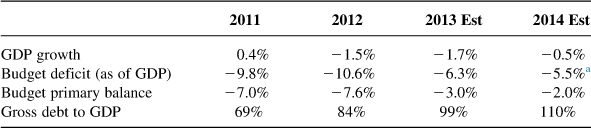

Everybody knows that debt sustainability requires fiscal discipline and tightening for several years. Whether we talk of Spain, Italy, or Greece, the country’s leadership must explain to all citizens that austerity is not a punishment. It is the correction of severe imbalances, over many years, between the sovereign’s income and its expenditures which led to near bankruptcy. Statistics help in studying the trend, and as Table 7.1 shows Spain has not yet learned its lesson.

It does not come as a surprise that southern European countries are under close scrutiny from financial markets, not least with respect to their spending habits and fiscal policies. Spain clearly missed its deficit targets for 2011 and 2012 and Brussels eased those of 2013 to avoid another deception. It serves nothing to initially announce a target deficit, then having it revised upward again and again.

While a deviation from target may be due to lower-than-expected revenues, the repetition of the same spending policies from one year to the next is budgetary mismanagement. The government is not really in charge. According to the European Commission’s forecast, Spain will miss the 2013 deadline for correcting its excessive deficit by a long way unless significant measures are taken—which are not likely.

Worse yet, considerable uncertainty has arisen regarding the state of the Spanish financial system, placing additional strain on Spanish public finances. Having obtained some euro 40 billion ($52 billion) out of a pledged euro 100 billion to beef up the treasuries of its badly wounded banks, Spain is hesitating to apply for support from the ESM, and therefore from ECB’s OMT program. Yet, continuous fiscal slippage will lead to rising costs of funding, pushing Spain into that program by default.

Financial analysts are of the opinion that even with OMT support longer Spanish bond yields would stay elevated as bondholders remain concerned about the country’s ability and willingness to implement necessary reforms over many more years; also about Spain’s de facto subordination to European Union guidelines. Neither is it sure whether:

• A fiscal union will be decided and established (in Euroland).

• A banking union would come once a fiscal union is established,

• Effective banking supervision at the ECB would be operational by 2014, and

• Euroland’s fiscal union will hold or fall apart over the next few years.

The message conveyed by these bullets is negative for Spain, Italy, France, and Euroland as a whole. Many risks are weighting on Euroland’s fortunes. The Spanish economy is about twice the size of Greece’s, Ireland’s, and Portugal’s put together. The ECB’s OMT rescue program would put a large dent in ESM’s coffers.

Theoretically, the common currency area has enough resources to finance a bailout, but the failure of the Greek rescue saw Euroland’s ability to influence economic policy weakened. The ECB might stand ready to intervene in secondary bond markets, pushing prices up and yields down. But if Spain falls behind in its economic reforms, as it looks like happening, it would give the ECB a black eye and at the same time damage the creditworthiness of other Euroland member countries.

Spanish slippages started showing up shortly after (in early April 2012) the new Popular Party’s government presented to the Spanish parliament a budget with euro 27 billion ($36 billion) of spending cuts and tax increases. These budget cuts hit Spain’s muscles rather than its fat. Instead of cutting the state wage bill and removing layers of bureaucracy, the budget cut spending on research and development. In addition, it was nobody’s secret that the central government had to rein in Spain’s 17 autonomous regions, responsible for most of:

Misfiring had an evident effect on investor confidence. At the April 4, 2012 bond auction, the Spanish government raised only euro 2.6 billion, shy of its euro 3.5 billion target. The yield on 10-year bonds rose to 5.7 percent while Spanish banks equities fell, as the ongoing sovereign-banking industry feedback loop added to investor doubts about the lenders’ asset quality.

Let’s face it. Not only because of economic but also due to political reasons Spain is at the abyss’ edge. Even after the hundreds of millions of euros made available by Mario Draghi to Spanish banks through the LTRO program their balance sheet did not improve. Instead, they used the ECB money to buy government bonds and bring down their interest rate. Critics said that Spain continues absorbing money like blot paper and still continues confronting the risk of default.

Other Club Med countries, too, live with the same illusions, but it is wrong to believe that ECB has bottomless pockets. Theoretically, it might print money at will; practically there is a limit. These funds come out if German, Dutch, Finnish, and other citizens’ pockets and only serve to mask Spain’s fiscal weakness. Moreover, suspicion exists that Spain’s (and Portugal’s and Italy’s) official debt numbers are questionable—a fact that the Spanish prime minister unofficially confirmed in March 2012 by canceling his still wet signature on Euroland’s Spanish budget deficit plan.

This unilateral act raised plenty of questions. The announcement that the country will not be able to fulfill its 2012 deficit target was a knife in the heart of its credibility. It has also provided another piece of evidence, if one was needed, that the euro crisis is far from being over.

Economists whose opinions contrast to those heralded after the different European Union “summits” and by the ECB, have said that Euroland’s current remedies doctor the symptoms of the common currency’s fundamental problems—not the illness. The illness results from the peripheral countries’

Sovereign balance sheet and valuation fundamentals are so much in disarray that even heads of neighboring countries find it necessary to speak out. In late March 2012, Mario Monti, the then Italian prime minister, said that Spain could reignite the euro risk.2 This is also true of the other Club Med member states. Southern European nations are not only overloaded with debt, they are as well uncompetitive both within the European Union and in the global market. If they wish to come up from under they have to:

• Work hard, very hard like the Icelanders did (Chapter 14).

• Swamp their weaknesses by restructuring their labor market and avoiding dilapidating strikes.

• Bet on their strengths to gain market prominence, and

• Do away with the habit of indebtedness as a “solution” to their social and economic troubles.

This requires leadership and cultural change which have not yet taken place. Those who hoped Spain will be able to put its worst problems behind it, have been disappointed. After some calming down as the ECB threw money to the problem, the country’s sovereign debt crisis has been gaining force again. Market volatility increases as the soothing effect of the ECB’s flood of funding for self-wounded member countries, and their banks, wanes.

Mariano Rajoy, Spain’s prime minister, may claim that he has been the victim of mistakes made by his predecessor socialist government. The uncontrollable rise in wages under José Rodriguez Zapatero, is an example. In the earlier years of the euro, Spanish labor wages rose significantly while German wages almost stagnated. German labor productivity moved ahead much faster than the Spanish (as well as the Italian, Greek, and French) productivity—with the result of leaving southern European economies in the dust.

Over the years of the common currency no Club Med politician, of the right or of the left, has cared to bend the curve of his country’s decline. Instead, business continued “as usual.” Yet the Club Med governments, the Spanish being one of them, have been well aware that an economy which is overextended, leveraged and weak in natural resources cannot afford to keep on carrying more and more debt.

Neither did the Spanish socialist government of the first decade of this century pay attention to the sorry state of Spanish banks (Sections 7.5, 7.6, and 7.7). Only on February 2, 2012, Spanish banks were told by the Rajoy government that they must find euro 50 billion ($65 billion) from profits and capital to finance a cleanup of their balance sheets, or those in weak position must agree to merge with another bank.

Luis De Guindos, Spain’s finance minister said that for the time being no public money was being used. This was only partly true. Spanish banks that needed state help had to apply for high-interest loans from the Fund for Orderly Bank Restructuring (FOBR), which reportedly planned to charge 8 percent interest. It did not happen that way as Euroland’s finance ministers after a couple of telephone conversations (unwisely) decided to throw euro 100 billion ($130 billion) to “solve” the Spanish bank’s treasury problems.

As it should have been expected not only was this money thrown down the drain but it also left the markets unconvinced. On June 19, 2012, LCH.Clearnet, the bonds clearing and settlements company, raised the margin (or extra deposit) it required from clients to hold Spanish government debt. The move had implications for the cost of funding for the country’s banks. Past margin increases on Ireland and Portugal were blamed for:

• Adding to problems at sovereign level, and

• Eventually pushing both countries toward a Euroland rescue.

Raising the margin to secure short-term funding to repurchase (repo) deals is a widely followed more stringent policy to dealing with heightened risk on debt. This was no arbitrary move by the clearer. LCH had on previous occasions imposed an additional margin requirement of 15 percent based on a number of factors, including when the yield spread between 10-year government bonds and a basket of euro AAA government-rated bonds rises above 450 basis points. Spanish debt was trading above that level.

7.2 Internal Devaluation Would Have Been the Better Solution

A preoccupation of any government confronted with the problems Spain has should be to shake up the supply side of its economy which is typically hamstrung by an inflexible labor market. The Spanish labor market’s ossification and exclusion of those who have no job3 hardly serves the interests either of companies or of the majority of workers—particularly the young who find no employment. In Spain (like in Greece) youth unemployment hit the rate of 53 percent.

When it came to power the Rajoy government signaled that it is committed to restructure the labor market and liberalize it, but so far nothing has really been done as labor unions oppose any talk of restructuring. People familiar with the EU’s bailout programs are of the opinion that:

• If the government does not have the force to enact changes which can filter through to the real economy

• Then the bailout’s chances of success will be nonexistent, no matter how much money is thrown to the problem.

Like the rest of southern Europe, Spain is saddled with a sclerotic service sector and inefficient manufacturing outfits whose high cost drags down exporters. The currency union was supposed to drive all of Euroland toward greater efficiency and lower costs, but no rules were set a priori on labor restructure and therefore the common currency contained the seeds of its own downfall.

• Spanish prices began to rise to uncompetitive levels after the euro was introduced, and

• Without an independent central bank, which could raise rates to chill inflation and without the will to take drastic measures the Spanish government fell into inertia.

Spain and the other higher-cost countries of Euroland lost their competitiveness, began running trade deficits and resorted to borrowing as their way out. Up to a point, surplus nations such as Germany, the Netherlands and Finland were willing to underwrite those deficits, but as the fiscal imbalances of Club Med continued the old Continent’s crisis began.

The Spanish government had the option of an internal devaluation, but it also had weak leadership and shock therapy was not popular (to say the least). Except for the traditional policy of devaluation the trade gap could not be closed. There was no way of putting the country’s goods on drastic markdown making at the same time imports impossibly expensive—as Solon had done in ancient Athens, besides cutting down on imports.

Yet Spain, like Italy, Portugal, Greece (and eventually France) had no other option than putting its house in order. It had to close the yawning competitiveness gap that caused its problems in the first place. As the Latvian experience has demonstrated (Chapter 13) internal devaluation may be a grinding process of cutting workers and employees’ pay while trying to improve their productivity, but it is also effective. Through it Latvia succeeded in:

• Correcting its budgetary imbalances, and

• Reducing the cost of living.4

However, internal devaluation is not conceivable without austerity, and “austerity” has been anathema to the Spaniards, though not to more disciplined northern European nations. From 2008 to 2012, not only Latvia but also Iceland as well as Ireland have been able to cut their unit labor costs, because there was a political will to do so and the common citizen cooperated.

This is not common among Mediterranean countries. True enough, among European countries Hungary topped the lot of sovereigns who confronted their problems with a unit labor cost decline of nearly 12 percent, due largely to a big currency devaluation which, as already explained, Spain could not do. As for Germany, it cut costs mercilessly for the first decade of the euro by applying an iron discipline, a concept totally alien to Spain.

The “solution” suggested by some economists regarding a southern European devaluation and northern revaluation within the euro framework has been impractical or, more precisely, impossible. There was talk of a northern euro (neuro) and a southern euro (seuro), but this was just that talk.

Spain had to cope with the fact that in the less competitive nations, costs are falling only because high unemployment takes away the workers’ bargaining power. There is as well the fact that if companies cut wages too much, employees can’t pay their car loans, mortgages, and other debts they have contracted. Household indebtedness sees to it that deep cuts create a vicious cycle.

Neither are short-term solutions a real fix. When China offered to buy Spanish bonds, financial analysts commented that the market recognized China’s intervention could bring only short-term relief. If anything, Chinese bond buying allowed to procrastinate over the radical reform required by the Spanish economy, which alone could give hope of a longer-term future.

By contrast, ECB’s intervention of August 8, 2010 in buying Spanish bonds was essentially perceived as a longer-term commitment. With this, the market sentiment changed and the yield on 10-year Spanish government bonds went from 6.3 percent down to 5 percent, though a month later it rebounded to 5.4 percent.

The macroeconomic and fiscal assumption underlying the Spanish economy, however, was not altered. Real GDP growth was nearly 0.7 in 2011, fell to −1.7 percent in 2012 and is forecast at between −1.0 percent and −2.0 percent for 2013 (the economists’ projections for 2013 originally ranged from −0.5 percent to −1.4 percent). The public debt has been projected to rise to 91 percent in 2013. What happens afterward is uncertain since the amount ultimately drawn by the Spanish government from ESM and ECB is not known.5

Several economists suggest that it could help if Spain requested an ESM bailout to trigger the “Unlimited” bond-buying plan announced by the ECB. Mario Draghi would be delighted to spend plenty of money. According to some accounts Spain’s gross financing need for 2013 will probably be a cool euro 250 billion ($325 billion)6—while according to other accounts Spain plans to borrow even more money in 2013.

In August 2012, Spain has been downgraded by independent credit rating agencies to BBB, while the increase in its debt ratio and funding stress may trigger further negative rating, taking Spain to junk levels. Indeed, on October 11, Spain was downgraded to a notch above junk. There is as well an elevated risk that the current mild, fiscal adjustment program falters as neither the government nor the public had their heart in it.

To the opinion of financial analysts, the large structural deficits of both the central government and Spanish regions (which also feature significant public debt), plus a weak banking sector, were quite likely to trigger a further increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio, pushing it toward 100 percent over the next couple of years and leading to another downgrade. Voices are raised that Spain requires:

• Debt reduction measures, and

• Policies able to assure the debt would be sustainable in the longer run.

As of the end of August 2012, the Spanish government had issued bonds at the level of euro 700 billion, but over and above that came the regions’ debt of about euro 150 billion; a large sum escaping central government control but obliging Madrid to come to the rescue. Therefore, debt reduction policies are urgently required at all levels even if the Spanish economy is squeezed by the deflating housing bubble, credit crunch, budget slippages, and government bond market stress.

The weak economy is hurting company profits, while banks continue piling up debt. All these factors see to it that the ongoing negative economic momentum is strong, while in the Spanish banking industry nonperforming loans are back to levels not seen since the first half of the 1990s. Spanish banks have become wholly dependent on Euroland and the ECB rather than laboring to improve their performance.

The Spanish banks are also facing another whammy. A Draconian mortgage law7 voted by parliament to protect the banks’ solvency forces families to go to extreme lengths to avoid succumbing to a default, but there are still many foreclosures. By November 2012, some 350,000 Spaniards had been evicted from their properties8 (over the past 4 years), a number which had much to do with the country’s 26 percent joblessness rate, and the way to bet is that this is going to worsen. Back in late April 2012, a Fitch report said repossessed homes were selling for just over half their initial valuations.

In conclusion, without an internal devaluation aimed at righting the balances, and labor restructuring to regain competitiveness, Spain will continue to weight on Euroland’s debt crisis. Due to the reasons which have been explained, no immediate solution can be expected. A vague reference to austerity aside, the government has not put forward any crucial measures to resolve the crisis at home, and this means that the effects of the Spanish debt crisis will continue being exported.

7.3 The Spanish Government Is Not in Charge

Critics say that it is not only the Socialist former prime minister, José Luis Rodriguez Zapatero who during his tenure dispensed public money left, right, and center (particularly during his last 2 years in office). It is as well the whole system which has been tuned to excessive deficits and therefore requires additional measures as well as the policy of living within one’s means.

Precisely because spending beyond the sovereign’s income has become a fad, considerable uncertainty has arisen regarding the state of the Spanish financial system and its ability to pay back its debts. Optimists say that the bulk of Spain’s troubles stems not from Madrid’s excessive budget deficits, but from the

• Construction and property market bubble, and

• Steady current account deficits, aggravated by declining business competitiveness.

While the message conveyed by these three bullets is correct, among them they don’t tell the full picture. Another key factor is Spanish politics. The country’s politicians have been consistently exploiting their country’s Euroland membership for national, regional, and other political ends, spending an awful lot of effort in largely symbolic gestures while avoiding hard decisions.

No wonder therefore that the Spanish debt still makes the news, with the country remaining at the receiving end of Euroland’s funds. As an example of avoiding urgently needed restructuring, Spanish retirement benefits have so far been untouchable while in Greece the Troika demanded that they are reduced by 40 percent, and this heavy haircut was voted into law by the Greek government.

Spain’s weak economy and the worsening of its public finances have refocused markets’ attention on the European debt problem and, more generally, on investment risks. Even if the current situation is far from being stellar, things would become less comfortable if economic disappointments were to coincide with a rise in social and political agitation reinforcing economic woes.

Investment risks have grown fed by years of easygoing and ill-studied credits, way beyond the fallen real estate. While the Spanish banks are in the frontline and they will take the first hit, behind them hides a “who is who” list of international banks. Figures published in April 2012 (latest available statistics) by the Bank for International Settlements show that at the end of 2011 German banks had $146 billion of exposure to Spain, more than the banks of any other country—with over a third of this exposure to Spanish banks and the balance to the private sector.

Deutsche Bank has been one of the largest foreign banks in the Spanish retail banking market (behind Barclays of Britain) with 250 branches and a euro 14 billion9 (nearly $18.7 billion) residential mortgage book. Other German banks too were big commercial property lenders at a time when most property values were so much higher, even if the Deutsche Bundesbank had identified property lending in countries such as Spain as a potential problem for the banks it supervises.

Commercial bankers should have listened to the central bank’s advice. They also should have known through their own studies that Spain’s financial industry was woefully undercapitalized, and they should have abstained from Spanish real estate lending.

Because of overexpansion and imprudent lending the weakness of the Spanish financial industry has been so pronounced that experts said at least a fraction of the real estate writedowns will have to be borne by the government, as the wounded Spanish banks had to confront the economic recession. Otherwise they were at risk of losing credibility with their clients, correspondent banks, and investors. The more the market’s focus shifted to the Spanish banks the more the sovereign felt the market’s heat.

While the market’s pressure softened with the early September 2012 announcement of OMT, that would allow the ECB to intervene massively in Spain’s debt market, Mariano Rajoy, the Spanish prime minister, has yet to give any firm signal that he is prepared to accept the main condition of such aid:

ECB’s announcement initially triggered a rally which removed some pressure off the Spanish government. But markets are unlikely to give the benefit of doubt for long; and investors are concerned by a statement in late September 2012—from the finance ministers of Germany, Holland, and Finland—who said plans to move bad assets off government books would not apply to legacy assets.

While swimming in red ink, the Spanish government also has to cope with angry street protests at home against fiscal austerity. These underline the existing political tension between northern and southern Europe. Part of the cost of shoring up the Club Med economies and pulling up from under self-wounded banks is the austerity they should adopt to rebuild their balance sheets. Euroland’s crisis will continue haunting financial markets.

With the Spanish government undecided on what to do next, by the end of September 2012, the cost of insuring against Spanish default by means of CDSs rose to a 3-week high of 400 basis points. Analysts said that even with LTRO and OMT Euroland failed to break out of the “complacency crisis” merry-go-round which characterized the past 3 years.

“The eurozone crisis has long been two steps forward, one step back,” says William Davies, head of global equities at Threadneedle, the investment manager. “The prospects of the ECB buying bonds and bank recapitalizations led to a period of euphoria, but now we’re taking a step back again.”10 Yet the Spanish government was offered good money (running after bad money) to fix its creaky finances before it was shut off from financial markets.

Relief in the markets is typically short-lived unless decisive measures are taken of handouts continue at rapid pace. The reason for continuing market pressure has been that Spain’s fiscal deficit, current account deficit, property and bank bust is compounded by a massive loss of investor confidence. Capital has drained from Spain at an accelerating pace for three reasons:

• Investors are worried by the vicious spiral of a weakening economy, worsening government finances, and banks at brink of bankruptcy.

• Economists were losing confidence in Spain’s place within the common currency, and

• Politicians have started to doubt that the poisonous links between the banks and the sovereign could be severed before it was too late.

A state of general nervousness was attested by the fact that rather than injecting the funds straight into the Spanish banking system, rescuers were lending them to the sovereign, which raised the public debt level. It could also see to it that Spain’s borrowing costs rise further as investors start questioning the government’s solvency.

To alleviate such fears, talks between the Spanish government and the European Union were focusing on measures that would be demanded by international lenders as part of a new rescue program, aiming to assure that they are in place before a bailout is formally requested. What Rajoy particularly feared is that the Commission would request more austerity measures to meet existing EU budget targets, which Madrid has repeatedly missed.

High in the Spanish prime minister’s mind has probably been the fact that ECB’s OMT sovereign bond buying would be triggered only after the government requests help from the ESM and there is an agreed reform plans. At the same time, bond buying by the ECB would lower Spanish borrowing costs somehow easing Madrid’s debt burden while increasing its level of debt.

A concept which, by all likelihood, is missing from Spanish government’s reasoning is the fact that fiscal discipline can be as effective in lowering borrowing costs as money from heaven. CDS risk premiums for Spain dropped drastically after the first LTRO (of December 2011), rose again and then sunk when the Fiscal Compact11 was announced and Spain let it be known that will go along. (Relatively speaking, the second LTRO of February 2012 had a rather minor effect on Spain’s CDS risk premium).

Investor confidence was further shaken by the fact that the recession in Spain deepened, driven by an accelerated decline in domestic demand; and various regions, including Catalonia, Valencia, and Murcia needed financial support from the central government, raising further concerns about the viability of the sovereign’s fiscal targets. The fact that Euroland’s Stability and Growth Pact put a limit at 3 percent for budget deficit and 60 percent for public debt ceilings made a sort of negative contribution because such ceilings have been breached chronically by member states, including Spain.

7.4 Investors Fear Spain Will Battle Against Austerity

Mid-April 2012 Spanish government bond yields broke above the critical 6 percent mark, and continued standing north of where they were before the ECB’s LTRO operations of December 2011 and February 2012. Traders’ eyes turned squarely back toward Euroland’s central bank, the only institution with the inclination to drive Spanish bond yields lower.

Critics nevertheless pointed out that while the LTRO cost was big—over $1 trillion—the rescues of Spanish and Italian credit institutions did not provide the expected results. The banks which got the LTRO funds at a mere 1 percent interest rate used them to buy their government’s bonds rather than rebuild their balance sheet. Moreover the central bank’s governing council was divided over this operation’s wisdom.

Neither have the public debt and the banks’ undercapitalization been the only problems. Parts of the nonbanking private sector’s debt became a burden for Spain’s public sector accounts, worsening the fiscal debt crisis. The country’s manufacturing industry was in poor shape because, as the reader is already aware, after the adoption of the euro rapid wage growth (and an influx of low-skilled immigrants) has caused a drop in

As if to make matters worse, while the Spanish labor market has long been plagued by rigidities, neither the Rajoy government nor the Socialist which preceded it had taken the initiative to right the balances. Critics said that this was not just a show of the government’s lack of guts but also, if not mainly, a Machiavellian calculation that Spain was simply “too big to fail.” Hence, if market pressures intensified support would be forthcoming from Euroland’s funds and the IMF.

Not all investors looked at this “too big to fail” argument as undisputable. Many have been worried by the fact that, according to estimates, an estimated euro 100 billion ($130 billion) of capital left Spain in 2011, and euro 160 billion ($205 billion) left Italy that same year—partly from each country’s citizens and partly as foreigners withdraw bank deposits or sold government bonds.

Neither were investors fooled by the calls in Paris and other Euroland capitals about “growth through more debt.” François Hollande, the French president, called for more spending and more taxes. In June 2012, Hollande, Mario Monti of Italy, and Mariano Rajoy of Spain teamed up to trap Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, into financing a silly spending-and-spending program, but their game fell flat.12

Economists who respect themselves and care for the opinion they are expressing, said that if high deficits were the answer, then Spain, Italy, Greece, and Portugal should be economies in upswing. This, however, they are not and they have no choice but austerity in their effort to pull themselves together, calm bond markets and avoid outright bankruptcy. Integral part of this opinion has been an undisputable fact of life. The debt of western economies has reached levels exceeded only during World War II and the evidence is that high debt stifles long-term growth.

• The first condition for reigniting the economy, therefore growth, is to rid oneself from the current mountain of debt, and

• The second condition is to remove uncertainty and its disastrous effect on most western economies, bringing back confidence.

How much sizable government deficits weight on the economy can be easily seen from the lack of trust investors have shown to the Spanish equity market—a proxy of the economy. Companies operating in Spain confront a shrinking market for their products and see their profits melting. Spanish equities excelled in volatility, which was generally low in 2012, as well as in negative values.

Mid-June 2012, Danone, the French food company, said Spain more than any other country was behind its steadily declining profit performance in southern Europe and that would shave half of 1 percent of its projected 2012 operating margins (Danone has been expanding into emerging markets for a decade to compensate for the uncertainty characterizing western markets).

Restoring investor confidence requires strong medicine. But are the measures being taken up to standard? On July 11, 2012, the Spanish government unveiled a euro 65 billion worth of tax increases and public spending cuts as part of a deal to secure European aid for the country’s banking system.13 As if to contradict Madrid’s action, that same day, thousands of miners marched on the center of the Spanish capital to protest against austerity measures which hit the coal’s industry’s subsidies.

In response to a tandem of demonstrations in Madrid and provincial capitals, Mariano Rajoy issued stark warnings about the risk to Spain’s future. What the Spanish prime minister did not say, but should have said is that while euro 65 billion looks like lots of money it is only a quarter of the funds the Spanish government is expected to need in 2013 to make ends meet—which, according to an estimate, stand at euro 250 billion (Section 7.3). And there is as well the massive euro 380 billion ($494 billion) property and construction overhang equivalent to 35 percent of Spanish GDP.

When it comes to antigovernment rallies, the Spanish are learning a great deal from the French and Greeks. When spending cuts are announced thousands of protesters demonstrated outside the Spanish parliament. However, analysts note that unlike protests held in 2011 when tens of thousands occupied the central squares of Madrid, Barcelona, and other cities, several 2012 demonstrations were isolated though violent clashes took place with police.

There is, as well, folklore. While Spain dearly depends on Euroland’s aid to avoid bankruptcy, animosity about largely political issues also has a field day. In early July 2012, Luxembourg and Spain have been at loggerheads over a board seat at the ECB which had to be filled. At a first time it was supposed to go to a Spanish banking official; but most Euroland governments backed Luxembourg’s candidate for the job. In retaliation Spain blocked his appointment until it gets another senior post for one of its bureaucrats.14

In addition, economists say that the money Spain gets from the EU is far from being optimally used because investments are not properly studied in terms of services and profitability. An example is the Ciudad Real airport, a euro 1.1 billion ($1.43 billion) white elephant. The last commercial flights ceased at the end of October 2011 (though the airport remains open to private planes). This is one of many examples of poorly planned spending in the past decade, during el boom. As money poured in, it was deviated to political pork barrels.

Most of Spain’s 17 regional governments channeled cash into trophy schemes with little or no concern for whether they would pay their way. The Ciudad Real’s airport, though private, was backed by the Castile La-Mancha region’s Socialist government in part funded by Euroland money and in part by a savings bank (caja) that went bust. At the end, the unnecessary airport filed for bankruptcy.

Other costs, too, have run out of control. Health care is an example and in this case Spain is in good company. All western countries are confronted by outsized public health care budgets. Health spending makes up between 30 percent and 40 percent of Spain’s regional governments’ budgets.

Like other westerners under a nanny state socialist regime, Spaniards enjoy free health care from cradle to grave. But an aging population, soaring drug bills, poor cost controls, and reduced tax revenues make this system unaffordable and unsustainable. Year-in, year-out, health budgets are allegedly overrun by over 15 percent. When tax revenues were steady, that could be handled up to a point. Now health care debt adds itself to the other public debt, worsening an already bad situation.

Aside other aftereffects, runaway health care costs add to the friction between the central government and the regions. The financial pressures on Madrid have been intensified by a constitutional crisis brewing over Catalonia. “Spain is increasingly slipping from his (Rajoy’s) hands,” said Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba, leader of the socialist party. “There are very clear fractures in Spain, and the one I am most worried about is social fracture.”15

Catalonia, Spain’s largest region by output, is also its most indebted; it is euro 42 billion in the red. End of August 2012, it got a euro 5 billion mini-bailout from the central government. Other regions followed the same policy of asking Madrid for funds. Economic vows fuel the secessionist mood, and regional governments blame their troubles on a national tax system which, in their view, obliges them to make disproportionate contribution to the rest of Spain.

Catalonia is by no means the only Spanish region in deep red. With half Catalonia’s GDP Valencia is also heavily indebted. The same is true of Andalusia, Spain’s most populous region, which requested a bailout from the central government. Along with Estremadura, Andalusia has a GDP per capita of euro 17,000 versus euro 30,000 for Madrid.

Catalonia’s money shortfall has led an increasing number of its citizens to conclude that their prospects for recovery would be enhanced by loosening or breaking ties with the rest of Spain. For the time being this is on hold, as the pro-independence center-right party did not benefit from recent elections to promote its program for independence. But for how long?

7.5 Spanish Banks and Euroland’s Taxpayers

For the virtually bankrupt Spanish banks, a challenging problem in search of a solution is that nobody really knows—including the Spanish government and the banks themselves—how deeply exposed they are, and whether their equity is positive or negative, as is the case of Bankia. This makes the search for way out from the Spanish banking crisis so much more complex, while the results expected from “this” or “that” fire-brigade action become more uncertain.

In mid-2012, when Euroland’s finance ministers started to have doubts about the Spanish government’s ability to recapitalize its banks, was advanced an estimate of euro 40 billion as being more or less enough for the recapitalization job. Shortly thereafter, however, it was said that this far from being enough, and filling the bottomless hole of Spanish credit institutions will require euro 90 billion ($117 billion), or more.

One of the key problems confronting both the central government and the Spanish banks is that no inflection point has shown up in credit quality. Bad news continue coming in. Good news is needed for provisions and subsidies to make a real difference. Spain has practically nationalized Bankia16 which in 2011 received euro 30 billion of state aid and in May 2012 required at least euro 10 billion more to survive; but all that money was used for fire-brigade operations—it was not employed to create a war chest.

It needs no explaining that depositors did not appreciate Bankia’s travails and part nationalization. Mid-May 2012, El Mundio, the daily newspaper, reported customers had withdrawn euro 1 billion of deposits since the government’s move.17 There has also been continued uncertainty over the final costs that Madrid will have to pay to clean up the partly nationalized lender.

Analysts noted that Madrid converted a euro 4.5 billion convertible bond into common equity in Bankia’s parent company,18 but it did not inject fresh cash nor did it decide on the final amount it will have to put into the lender. The move was primarily intended to stem a “run” at the wounded credit institution, which suggests that the Spanish government’s cash injections left much to be wanted in salvage terms.

For its part, the ECB was reluctant to come forward, as Maria Draghi waited for results of the then forthcoming Spanish elections, and kept some dry power to eventually negotiate a bailout. The EU Commission, too, has been holding back in spite of verbal (but only verbal) comments made by its top brass that “the time for Spain is running out.”

As friendly but empty of substance verbal exchange continued, soaring losses of Spanish banks cast doubt on the estimated public cost of propping them up. The crucial question among Euroland bureaucrats, politicians, and Spanish bank observers was “What would be enough?” Some estimates suggested Spanish banks would need as much as euro 60 billion; others spoke of euro 100 billion; still others of euro 300 billion ($390 billion).

According to other accounts the loans books of 14 Spanish banks showed that more than half of them did not have enough capital. The two major banks: Santander and BBVA as well as Caixabank seem to have been able to meet Basel IIIs 9 percent core Tier 1 target—but not the other banks, which included Sabadell, Bankinter, Unicaja, Banco Mare Nostrum, Banco de Valencia, Catalunya Bank, Bankia, and many more.

In power since December 2011, Mariano Rajoy’s government was at once confronted by central government deficits, regional government deficits and the big red ink holes in the treasuries of Spanish banks. Rajoy seemed to think he can perform feats that his Socialist predecessor could not. He set the regions new targets and asked the banks to recapitalize themselves with private money. Neither of these targets worked out.

As direct consequence of slow-motion recognition of the Spanish banking industry’s financial problems, the central government found itself in an impasse. Critics said that the contemplated banking industry recapitalization did not address the basic issue coming from the fact that Spanish banks are highly reliant on wholesale funding. To make matters worse, the relative scarcity of deposits also increased as a consequence of deposit outflows. There was therefore no alternative than to reduce the risk-weighted assets (RWAs) which the Spanish banks registered.

The Spanish banks’ RWAs are a conglomeration of credit risk (by far the large share), market risk, and operational risk. In late 2012, RWAs at Santander stood at euro 560 billion; at BBVA, euro 340 billion; Caixa, euro 195 billion; Bankia, euro 165 billion; Popular, euro 100 billion; and Sabatel, euro 80 billion. Among themselves the next 10 in line Spanish banks featured euro 325 billion in RWAs.19 The total is an astronomical euro 1765 billion (nearly $2.3 trillion).

Indeed, conditions set by the European Commission required that Spanish banks reduce their loans-to-deposits ratios from a prevailing 150–160 percent level toward 110–120 percent (the way it happened in Portugal and Ireland). The Spanish banks however answered they cannot rapidly reduce their mortgage portfolios, which represent about 40 percent of loans, and what the EU demanded would require a sharp reduction of company loans, representing another 40 percent.

In fact, the downsizing of company loans creates another vicious cycle by bringing in evidence the nonperforming loans which, along with bad real estate loans, continued to depress the banks’ balance sheets. This further complicates the other problem confronting Spanish banking: their covered bond issuance. Spanish banks have extensively issued covered bonds with a total outstanding amount estimated at euro 350 billion ($455 billion), using large parts of their mortgage book as collateral.

While these numbers are big and pose many challenges, the worst of all is that by all likelihood they will continue to increase. On December 18, 2012, just prior to the end of the year, it was announced that Spain’s bad loans ratio has grown to an all-time high.20 Experts say that the Spanish banks’ bad loans ratio will continue going north as the worst-case scenario turns real.

There is plenty of evidence, therefore, as to why Spanish banks heavily depend on the ECB for liquidity. They have borrowed a record amount of money estimated at 25–30 percent of Euroland’s total. Even so they are struggling to increase provisions and capital during a recession. Needless to say that they will need a huge amount of extra funds if the economy deteriorates more than predicted. How much more?

Nobody can answer this query in a sure way. The Spanish government depended on a “bottom-up” review of 115,000 loans,21 conducted by two consulting companies with close international supervision from authorities, including the IMF and ECB. Rajoy’s hope was that the results will dispel doubts over the true extent of losses in the Spanish banking industry. This has been largely wishful thinking.

Overall, the total shortfall computed by the Oliver Wyman study dropped to euro 53.7 billion after including deferred tax assets and ongoing mergers, according to the reports. But several Spanish bankers have been critical of the process, attacking it for “weakening” banks and adding “confusion.” While to the opinion of financial analysts, neither of the two aforementioned studies dispelled the uncertainty about the depth of the red ink hole in Spanish banks’ capital.

The analysts argued that with the banks having suffered a sharp fall in share price, and the capital markets all but closed to most Spanish lenders, it will be a grueling process for them to borrow money let alone sell new shares. Even if this were possible, it would have been highly dilutive for existing investors.

Back in October 2011, Luis Faricano of the London School of Economics had estimated that the capital required could total up to euro 100 billion, around 10 percent of Spanish GDP. To his opinion, the banks would not be able to raise that much money in a hurry, and Spain would have to seek help from Euroland.22 Many months later Euroland’s ministers of finance worked around this euro 100 billion estimate, in the understanding that:

• It will target the problem of large amounts of nonperforming assets held by Spanish banks,

• But it should not reduce the incentive for the banks to deleverage their balance sheets.

Several analysts and economists expressed the opinion that something is wrong with the logic behind these two bullets. Too little money would not solve the Spanish banks’ problems; but too much will exacerbate the vicious cycle linking government and bank finances. It will as well inhibit the banking sector from cleaning up its balance sheet.

Experts believe Spain must follow the example of other countries that have been through similar banking crises, setting up one or more bad banks (Section 7.7) to work through the maze of nonperforming loans and eventually dispose them. This policy would force the banks to mark assets down to realistic levels, but with the banking crisis in full swing realism has been the most vital missing ingredient.

Reducing their balance sheet’s leverage would be the best policy, but Spanish banks say that at this very moment cash is king and since mid-2011 they had few opportunities to attract unsecured funds. They therefore stick to the priority of finding capital even if most of their liquidity is drawn from collateralized funding offered by the Bank of Spain and the ECB (which takes its money straight out of the pockets of Euroland’s taxpayers).

7.6 In Financial Terms Spanish Banks Wounded Their Clients23

Spain is in the danger zone both because of fiscal reasons and due to the fact its banking industry is in shambles. The central government does not have the hundreds of billions of euros needed to recapitalize the country’s credit institutions, finance the regions and pull itself up from under. This problem of very shaky finances has been known for years by Zapatero’s socialist government, but the former prime minister has shown no rush to fix it. He cared more to block the takeover of Endesa, the Spanish energy company, by Germany’s EON, than to fix his country’s leaky roof.

All this is typically socialist government doing and it has been quite superficial. A few years later, in 2012, superficiality characterized the “unanimous decisions” by Euroland’s finance ministers (who were spending “only” taxpayer money) to recapitalize the Spanish banks without any questions asked. A short time thereafter, at the end of July 2012, Euroland allocated to this vague and poorly documented financing an approximate figure of euro 30 billion, raised on November 29, 2012 to euro 37 billion ($48 billion). The money was supposed to come out of EFSF till ESM is operating.

Critics said that so much money thrown at the problem was an unwarranted spoilage. Moreover, the euro 100 billion might calm down for a few weeks the markets confronting Spanish economic and financial problems, but they will not be a cure—the more so as the Spanish banks themselves estimated the needed capital injection at the level of euro 300 billion ($390 billion).24

The problem of pulling Spain and its banking industry up from its descent to the abyss is complex, as evidenced by the fact that the Spanish government tries to separate the banking crisis from the sovereign debt crisis, and it does not even succeed to go halfway in this direction. There is as well the fact that both the banks and Madrid are suspected of not being truthful with their statistics. “The EU smiled as Spanish banks cooked the books,” said one of the critics.25

Many European Union countries which have had, and still have, banking problems of their own have found out that the sovereign debt and banking debt are so closely connected that they cannot be split in a neat way. Neither is it rational to spend a big chunk of a loan the Spanish government will probably contract with Euroland on the banking industry. In principle, the money going to beef up banking capital should come from the banks themselves by liquidating some of their assets.

Quite likely, Madrid knew some secrets when it wanted the money in a hurry but it would accept neither accountability nor responsibility on how it will be used. The Spanish government was angry that the package came with a clause requiring to write down investors who had bought hybrid debt from the country’s financial institutions to be bailed out through Euroland money. This preferred treatment of its retail investors added insult to injury already suffered by Euroland’s taxpayers, who were forced to foot this very poorly studied “salvage.”

Spanish bankers had sold risky instruments to unsuspecting common citizens who did not know that there is money to be lost with derivative financial products linked to preference shares. Nobody ever assumed responsibility for mis-investments sold to unaware customers who subsequently feared that their lifetime savings will be wiped out. Several cases of mis-selling were so blatant that:

• Writedowns are likely to cause a backlash against both the government and the banks, and

• Infuriated depositors started pulling their money out of the Spanish banks involved in this scam, aggravating their precarious situation.

In the casino society of ours Spanish and other banks have acquired the habit of loaning their retail depositors with preference shares which, technically speaking, are bonds not equity. They are senior to ordinary shares, but subordinate to bonds. Even in a casino society, however, preferred share issuers and investors cannot have it both ways. Regulators should abide by—and enforce—the gold standard of pure, loss-absorbing pecking order:

Banks should be punished for selling their customers complex products which they don’t understand, and one day they will blow up and sink their savings. Take as an example the use of a derivative instrument designed around euro/US dollar currency exchange. The offered structure is known as one touch. The bank’s client effectively enters in a forward contract on euro/dollar rate with a barrier. If at any time before maturity the spot rate breaches the barrier the client would receive leverage return of his or her initial investment. If not (which is likely) the capital being bet is lost.

Plenty of economists and financial analysts said that Brussels should resist the investor reimbursement plan which Madrid pressed on Euroland to mollify savers. Critics stated that using EFSF funds for repaying investors goes against the principle that creditors should take a hit before taxpayer money is injected into a bank in difficulty.

• Euroland money should not be used to refund private interests, and

• Banks and bankers who by words or acts cheated savers should be punished.

Integral part of the moral hazard we are talking about is the compensating of sophisticated savers who consciously sought high returns when buying the Spanish banks’ hybrid debt. Critics added that Madrid should also assure that acts of mis-selling are not being repeated, amending the Spanish law to prevent such practices from reoccurring, as well as making Spanish banks and their accounts totally transparent.

While this has been a sound advice, it did not find its way to Spanish legislation probably because of conflicts of interest. Delays also characterized the so-called bad bank (Section 7.7), to be instituted and financed by the government, with the mission to purchase at heavy discount the Spanish banks’ nonperforming loans allowing them to:

The presence of moral hazard should not be ignored even in an emergency, by letting mismanaged banks (and their tricky instruments) escape unscathed. When rules are drawn up for bailouts it is hard to justify the turning of a blind eye to the scams. A cleanup will lead to better resource allocation in the economy and moral risk should not be permitted to persist. After all, the ECB/ESM money comes out of the pocket of German, Dutch, Finnish, and other taxpayers who will be badly cheated if the cleanup is half-baked.

This is only one of several cases with which should be directly confronted the new bank regulator for Euroland, under the ECB. Already the question of when this authority will be created, and what powers it will have, has caused a storm in some Euroland capitals. The ambiguities which persist are forcing several sovereigns to backtrack on soft commitments others thought had been finalized.

To be successful the new supervisory framework will be required to provide firm solutions to many tricky issues. For example, there are clear signs of clashing views about the amount of debt Spain would be saddled with once the bank rescue system is complete and operating. Officials from several Euroland countries insist that, in the end, Madrid must still guarantee at least some of the losses the ESM would face if rescued banks defaulted—which by all likelihood they will do.

Therefore, a critical question has been how strong should the rescue link between derelict Spanish banks and their indebted sovereign. This is a question which concerns all of Euroland’s sovereigns as well as all of the banks. In Spain’s case part of the difficulty has been associated to the fact that the Spanish banks’ bad debt rose to the stars.

The sovereign will be confronted with plenty of losses to carry on its balance sheet if several of the country’s banks default. With OMT Mario Monti has already positioned himself to come to the rescue by buying Spanish bonds. This however does not mean that the Spaniards get a free lunch. Germany has already clearly stated that outside inspectors will supervise the euro 100 billion emergency loans for Spanish banks, just like other financial bailouts over the past 2 years—even if Madrid insists that it should escape the onerous conditions imposed on Portugal, Ireland, and Greece (a request which evidently makes no sense).

7.7 Bad Banks and Wanting Spanish Fiscal Policies

Bad banks is a term used to describe financial entities set up and backed by management’s own initiative or (more often) by governments to facilitate the removal of “bad assets” from a going entity’s balance sheet. This is supposed to give a lease of life to wounded credit institutions. “Bad assets” are loosely defined as those that:

• Are at risk of severe impairment, and/or

• Are difficult to value or, when valued, worth very little in comparison to their book value.

Bad banks are created to assist in the resolution of a financial crisis; permit refloating the wounded bank by relieving it of its worst “assets” (including holdings and nonperforming loans); and try to recover the most of what may be seen as lost money, by avoiding a fire sale of those wounded “assets.”

The first case of a bad bank arose in 1988 when the Mellon Bank spun off its energy and property loans, which had turned sour, into Grant Street National Bank. The latter was financed with junk bonds and private equity. A successful example of a government-sponsored bad bank has been Sweden’s Securum, engineered in the early 1990s to relieve Nordbanken of its mountain of bad loans and private equity holdings.

As these examples demonstrate, the bad bank idea is flexible and it can be given different interpretations at different times by different people. But success is in no way guaranteed. Much depends on the nature of the “bad assets,” market conditions and how well the disposal operation is being managed. Josef Stiglitz, the economist, criticizes the bad bank idea as “swapping cash for trash,” but the pros say such an approach has advantages:

• An independent entity can focus on the job of recovering the fair value of wounded assets, and

• Taking toxic assets off the balance sheet of a bank teetering on bankruptcy leaves behind a cleaner credit institution, which should find it easier to raise capital or attract a buyer.

Finding a buyer at fair value price, however, may well be a pipe dream. In addition, the real problem with bad banks is that, as usually, the taxpayer will be asked to foot the bill. Someone has to pay for the assets transferred by the wounded bank to the new equity, or to a buyer, at deep discount.

The transfer of big chunks of a loan portfolio, specifically nonperforming loans and similar “assets,” from a credit institution to a specially set up vehicle will take the form of the former selling them to (which may be the government, or its agent) at large discount. Superficially, this is similar to a securitization transaction but in reality it is not as it raises the questions of:

If, and only if, this operation is properly done and conflicts of interest are avoided, transfer of nonperforming loans to a bad bank buys breathing space since (presumably) the new entity is under no pressure to go ahead with sale of wounded assets. Theoretically at least, it can wait till market conditions improve to get its money back or even make a profit.

In the 1990s Sweden’s Securum was able to dispose Nordbanken’s nonperforming assets it was entrusted with at 75 to 80 cents to the kroner—while they would have fetched much less than 50 percent in a fire sale. Securum however was very well managed and acted in full independence from Nordbanken. This is not the general case with bad banks.

Neither are all assets in a portfolio of dubious securities able to fetch 80 cents to the dollar, and this is true of both commercial banks and central banks. Many economists and financial analysts worry that that’s the case with what can be found in the vaults of the Federal Reserve, Bank of England, and ECB. An Italian banker characterized these positions as garbage worse than in the streets of Naples. No doubt the Bank of Spain has plenty of them, even if the real mountains are to be found in the Spanish commercial banks and savings banks.

Confronted with a rapid escalation in the amount of funds necessary to buy the Spanish banks bad loans and other useless “assets,” even at big discount, Madrid does not want to put up any money. In theory, moving bad property loans off Spanish banks’ balance sheets looks attractive. In practice, this makes sense only if someone acquires them. This “someone” must:

Early on, the Spanish government’s hypothesis on who will be the acquirer was vague envisaging a corporate entity financed either by local deposit guarantees, by the domestic banking sector collectively, or by unspecified “private” investors. Anecdotal evidence suggests that little attention is paid to the fact that a basic requirement connected to the bad bank concept is to limit as much as possible the risk of spreading toxic waste to even more banks or other entities.

For a bad bank project to be effective, reliance on public funding is a “must,” but the Spanish government is short of funds. To make matters more complex, as many analysts noted, valuing bad property loans and properly reflecting their remaining worth (if any), is no easy business either.

Even if the “right price” is guestimated, this will remain exposed to further price declines—an issue particularly true of Spanish real estate where there is a huge amount of surplus property in an ailing economy. Worse yet, the overhang of bad bank-owned assets can turn into a factor preventing stabilization of Spain’s property market.

Nobody can tell in advance how many cents to the euro the Spanish bad bank will recover. The rumored 70–80 cents is a pipedream. Even half that may be too much. The difference between what is recovered and the face value of the bad loans being taken over will be paid by somebody, and the way to bet is that that’s the Spanish taxpayer.

Madrid has to review its fiscal policies (which are currently wanting) to account for that load. This brings into the picture the Troika to supervise the eventual euro 100 billion Euroland loan for the Spanish banks as well as all other Euroland money flowing into Spain for the bailout, including the Spanish bonds bought by ECB under OMT.

The Spanish government is caught in a dilemma. Economists say the country’s real estate crisis is so dire that weak banks risk falling by the wayside without a chance to clean up their balance sheets. According to political commentators, Mariano Rajoy sidetracked the issue when he said that Spain needs, and needs urgently, deep structural changes. Without lots of capital to buy up the bad assets, the bad bank will be a sort of window dressing.

In addition, several Spanish ministers have been against the bad bank idea, as first reaction, though by October 2012, the government was poised to set up a Banco Malo. This has been counterproductive because confidence in Spain and its banks has been further shaken by the procrastination on:

Investors still question banks’ asset valuations, and whether bad loans will be transferred at their right price. According to some opinions nearly all property loans, good and bad, including property developer exposure with a face value of between euro 1.3 and euro 1.5 trillion, could end up in the bad bank.26 This is a huge amount of money even with a brutal haircut, raising inter alia the question: Will the bad bank really work?27

As if to make matters even more obscure, on December 18, 2012, the ticker at Bloomberg News carried the message that, according to Madrid, private investors already subscribed to 55 percent of Spanish bad bank’s capital. No information was given as to who are these private investors, to make such a news item believable.

Forcing investors in some of the banks’ debt to take losses was a condition imposed by Euroland’s contributors to the bailout funds, to minimize the burden on taxpayers (Section 7.6). But a bad bank is a separate, independent entity and this radically changes the answer to the query: “Who is responsible for its losses?” The answer is its owner, and if the owner happens to be the government, then so be it.

Neither is the bad bank the only elephant in Madrid’s financial glass house. Several of the Spanish banks who, after shedding some of their bad loans, optimistically hope to return to profitability, may still go under since their financial staying power is questionable. All the bad bank will do it to take on dud loans. There is no guarantee that Spanish banks will be able to regain the market’s confidence as Madrid hopes.

All counted, the picture for Spain is not that pretty. In 2013, the country confronts “a further fiscal contraction equivalent to 4 percent of GDP to set its finances on a sustainable path, and a loan-to-deposit ratio of nearly 180 percent leaves its banking sector vulnerable of funding crises,” states a study by UBS.28 As in the case of Portugal and Greece, how and how well Euroland’s and IMF’s money is employed in Spain, and whether Madrid sticks to its obligations for a bailout, will be controlled by a Troika (consisting of Euroland’s, ECB’s, and IMF’s representatives).

The money will come from ESM which in OMT terms Spain must approach with a request for financial help, and the loans will carry preferred status to Madrid’s existing sovereign debt. The ESM is senior to other creditors, assuring that Spain’s debts to other Euroland members would take precedence over private lenders in the event of a default.

This is not money to be spent at will even if Mariano Rajoy called his decision to seek as much as euro 100 billion in funds “the opening of a line of credit” for the country’s banks, rather than a bailout with strict external monitoring of its economy. Rajoy also said owners of existing sovereign bonds would not be affected—which is patently false if the money comes from ESM.

In the first quarter of 2011, the yield of Spanish 5-year government bonds stood at 4.5 percent. It peaked to about 6 percent in December 2011 but with Mario Draghi’s LTRO (of which Spanish banks benefited handsomely, using the borrowed billions at 1 percent interest rate to buy government bonds) the 5-year bonds yield dropped to 3.5 percent. Then it rose again to nearly 7 percent.

To help Spain and Italy the ECB announced OMT and made the commitment “…to do what it takes…” The market liked this announcement because “it saw euros now.”29 The interest rate on Spanish 5-year bonds dropped to about 4.5 percent (where it was earlier on, even if neither Spain nor Italy joined the OMT saga. Critics say that in spite of LTRO and OMT the ECB has failed in altering the market’s perception and therefore lost some of its credibility.

It therefore comes as no surprise that policy makers in Brussels and Euroland worry that privileging emergency loans over existing sovereign debt, through the use of ESM, would spook the bond markets. Facing more risk of losing their investment in the case of a default, investors would demand higher premiums from Spain. In turn, this will drive interest rates up instead of down. (It did not happen yet.)

Precisely the same will take place if “most favorable” conditions are awarded to Italy which, due to 4 months without government and prevailing political uncertainty, was in its way of undoing whatever prudent fiscal measures were put in place by Mario Monti’s administration. Economic history shows that weaknesses are provocative, but at the same time the Spanish, Italians, French, Greeks, Cypriots, and Euroland at large know that there is no chance for wholesale change in European Union policies.

1In Euroland, Spain and Greece share the worst possible statistics. In Spain, general unemployment is 26.5 percent and youth unemployment 56.6 percent. In Greece, unemployment statistics stand just below these numbers.

2Bloomberg News, March 25, 2012.

3Which also exists in all other Club Med countries.

4Latvia chose to keep the peg of its currency unaltered, though it could have devalued. Because of this peg, Latvia’s can be taken as proxy to that of a country which cannot devalue having adopted the common currency.

5Much depended on whether Spain asks for bailout. The only known red ink was the euro 100 billion ($130 billion) earmarked to recapitalize Spanish banks.

6The Economist, November 17, 2012.

7Under a 100-year-old law, returning the keys of ones’ property to the bank does not rid him of his debt. A bank can seize a home for 60 percent of its appraised value, and then pursue the owner for the outstanding difference including interest and legal fees.

8This is softened by a new law.

9Deutsche’s first quarter 2012 report showed euro 29 billion of gross exposure to Spain but the bank said collateral and other hedging brings net exposure at about euro 14 billion.

10Financial Times, September 27, 2012.

11Chorafas DN. Breaking up the euro: the end of a common currency. New York, NY: Palgrave/Macmillan; 2013.

12Idem.

13Cuts include a rolling back of unemployment benefits, an increase in value added tax (from 18 to 21 percent) and a reduction to local government subsidies.

14Financial Times, July 10, 2012.

15Financial Times, September 27, 2012.

16Bankia has been the result of wider merger of Spanish savings banks primarily, but not exclusively, wounded by their real estate loans. By the third quarter of 2012 Bankia was deemed to need euro 25 billion up from euro 19 billion capital gap identified only a few months earlier. Then, mid-December 2012, came the news that Bankia had a negative net worth of euro 4.1 billion. Banco Popular was another listed bank in deep troubles, Spain’s sixth biggest lender.

17Financial Times, May 18, 2012.

18Banco Financiero y de Ahorros (BFA).

19Statistics from Financial Times, October 1, 2011.

20Bloomberg News, December 18, 2012.

21These 115,000 individual loans were picked at random and individually examined by a team of auditors. Critics attacked the narrow focus of this exercise, echoing the 2011 Europe-wide stress test of Euroland sovereign debt which failed to extrapolate the risk of sovereign default to other related risks like funding costs.

22The Economist, October 8, 2011.

23Italian banks did something similar when, a short time prior to Argentina’s bankruptcy, sold Argentinean government bonds to their clients.

24Euronews, June 14, 2012.

25Bloomberg News, June 15, 2012.

26Officials in Brussels said some euro 45 billion in Spanish banking assets would be transferred to it.

27Other things equal, its chances for success will be greater if it has a life cycle of 7 or 8 years rather than being allowed to become another permanent bureaucracy.

28UBS, CIO Year Ahead, December 2012.

29At the end it proved to be only an illusion.