Prices, Exchange Rates, and Purchasing Power Parity

Abstract

The tendency for similar goods to sell for similar prices globally provides a link between prices and exchange rates. As prices change internationally, exchange rates must also change to keep the prices measured in a common currency equal across countries. In other words exchange rates should adjust to offset differing inflation rates between countries. This relationship between the prices of goods and services and exchange rates is known as purchasing power parity (PPP). It is important to study the relationship between price levels and exchange rates in order to understand the role of goods markets (as distinct from financial asset markets) in international finance. This chapter explores this relationship through discussions of absolute PPP, relative PPP, the Big Mac index, and deviations from PPP. Also discussed is the relationship between time, inflation, and PPP. Real exchange rates are examined, as compared to the nominal exchange rate. This chapter concludes with an appendix on the effect of relative price changes on PPP, using a real-world example.

Keywords

Absolute purchasing power parity; Big Mac index; exchange rate; foreign exchange; nominal exchange rate; overvaluation; PPP; price index; purchasing power parity; real exchange rate; relative purchasing power parity; undervaluation

Chapter 1, The Foreign Exchange Market, discussed the role of foreign exchange market arbitrage in keeping foreign exchange rates the same in different locations. If the dollar price of the yen is higher at Bank of America in San Francisco than at Citibank in New York, we would expect traders to buy yen from Citibank and simultaneously sell yen to Bank of America. This activity would raise the dollar/yen exchange rate quoted by Citibank and lower the rate at Bank of America until the exchange rate quotations are transaction costs close. Such arbitrage activity is not limited to the foreign exchange market. We would expect arbitrage to be present in any market where similar goods are traded in different locations. For instance, the price of gold is roughly the same worldwide at any point in time. If gold sold at a higher price in one location than in another, arbitragers would buy gold where it is cheap and sell where it is high until the prices are equal (allowing for transaction costs). Similarly we would expect the price of tractors or automobiles or sheet steel to be related across geographically disparate markets. However, there are good economic reasons why prices for some goods are more similar across countries than others.

This tendency for similar goods to sell for similar prices globally provides a link between prices and exchange rates. If we wanted to know why exchange rates change over time, one obvious answer is that, as prices change internationally, exchange rates must also change to keep the prices measured in a common currency equal across countries. In other words, exchange rates should adjust to offset differing inflation rates between countries. This relationship between the prices of goods and services and exchange rates is known as purchasing power parity (PPP). Although we are hesitant to refer to PPP as a theory of the exchange rate, for reasons that will be made apparent shortly, it is important to study the relationship between price levels and exchange rates in order to understand the role of goods markets (as distinct from financial asset markets) in international finance.

Absolute Purchasing Power Parity

Our first view of purchasing power parity (PPP) is absolute PPP. Here we consider the exchange rate to be given by the ratio of price levels between countries. If E is the spot exchange rate (domestic currency units per foreign unit), P the domestic price index, and PF the foreign price index, the absolute PPP relation is written as:

(7.1)

For those readers who are not familiar with price indexes, P and PF may be thought of as consumer price indexes or producer price indexes. A price index is supposed to measure average prices in an economy and therefore is subject to the criticism that, in fact, it measures the actual prices faced by no one. To construct such an index, we must first determine which prices to include—that is, which goods and services are to be monitored. Then these various items need to be assigned weights reflecting their importance in total spending. Thus the consumer price index would weight housing prices very heavily, but bread prices would have only a very small weight. The final index is a weighted average of the prices of the goods and services surveyed.

Phrased in terms of price indexes, absolute PPP, as given in Eq. (7.1), indicates that the exchange rate between any two currencies is equal to the ratio of their price indexes. Therefore the exchange rate is a nominal magnitude, dependent on prices. We should be careful when using real-world price index data that the various national price indexes are comparable in terms of goods and services covered as well as base year (the reference year used for comparisons over time). If changes in the world were only nominal, then we would expect PPP to hold if we had true price indexes. The significance of this last sentence will be illustrated soon.

Eq. (7.1) can be rewritten as

(7.2)

so that the domestic price level is equal to the product of the domestic currency price of foreign currency and the foreign price level. Eq. (7.2) is called the law of one price and indicates that goods sell for the same price worldwide. For instance, we might observe a shirt selling for $10 in the United States and £4 in the United Kingdom. If the $/£ exchange rate is $2.50 per pound, then P=EPF=(2.50)(4)=10. Thus the price of the shirt in the United Kingdom is the same as the US price, once we use the exchange rate to convert the pound price into dollars and compare prices in a common currency.

Unfortunately, for this analysis, the world is more complex than the simple shirt example. The real world is characterized by differentiated products, costly information, and all sorts of impediments to the equalization of goods prices worldwide. Certainly the more homogeneous goods are, the more we expect the law of one price to hold. Some commodities, which retain essentially the same form worldwide, provide the best examples of the law of one price. Gold, for instance, is quoted in dollar prices internationally, and so we would be correct in stating that the law of one price holds quite closely for gold. However, shirts come in different styles, brand names, and prices, and we do not expect the law of one price to hold domestically for shirts, let alone internationally.

The Big Mac Index

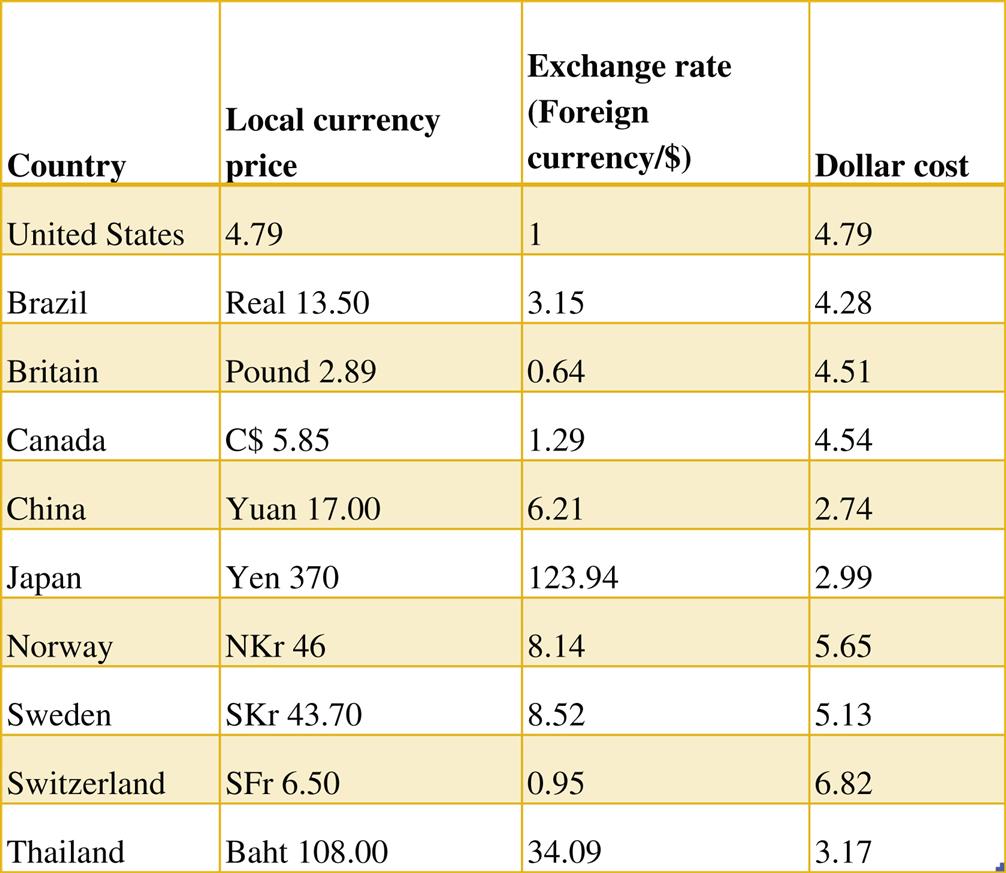

Fig. 7.1 illustrates how a Big Mac is priced differently in different countries. The first column shows the price in local currency and the third column shows the implied price in dollars. The figure indicates the cost of a Big Mac varies drastically across countries. In China a Big Mac costs the equivalent of $2.74, much less than the $4.79 a Big Mac costs in the United States. In contrast a Big Mac costs the equivalent of $6.82 in Switzerland. If you have traveled extensively abroad you are aware that wide discrepancies exist between prices of similar products and services across countries.

One might wonder why we would ever expect PPP to hold, since we know that international trade involves freight charges and tariffs. Given the costs associated with shipping goods, we would not expect PPP to hold for any particular good—so why would we anticipate the relationship phrased in terms of price indexes to hold as in Eq. (7.1)? Furthermore not all goods are traded internationally, yet the prices of these goods are captured in the national price indexes. As the prices of nontraded goods change, the price indexes change. But this does not affect exchange rates since the changing prices of nontraded goods does not give rise to international trade flows, and so no change in the supply and demand for currencies need result. Recently economists have added many refinements to the analysis of PPP that we need not consider here. The important lesson to be learned is the potential problem associated with using price indexes to explain exchange rate changes.

So far, we have emphasized variations in the exchange rate brought about by changing price indexes or nominal changes. However, it is reasonable to assume that much of the week-to-week change in exchange rates is the result of real rather than nominal events. Besides variations in the price level due to general inflation, we can also identify relative price changes. Inflation results in an increase in all prices, but relative price changes indicate that not all prices move together. Some prices increase faster than others, and some rise while others fall. An old analogy that students often find useful is to think of inflation as an elevator carrying a load of tennis balls, which represent the prices of individual goods. As the inflation continues, the balls are carried higher by the elevator, which means that all prices are rising. But as the inflation continues and the elevator rises, the balls, or individual prices, are bouncing up and down. So while the elevator raises all the balls inside, the balls do not bounce up and down together. The balls bouncing up have their prices rising relative to the balls going down.

If we think of different elevators as representing different countries, then if the balls were still while the elevators rose at the same rate, the exchange rate would be constant, as suggested by PPP. Moreover, if we looked at sufficiently long intervals, we could ignore the bouncing balls, since the large movements of the elevators would dominate the exchange rate movements. If, however, we observed very short intervals during which the elevators move only slightly, we would find that the bouncing balls, or relative price changes of individual goods, would largely determine the exchange rate.

Relative Purchasing Power Parity

There is an alternative view of PPP besides the absolute PPP just discussed. Relative PPP is said to hold when

(7.3)

where a hat (^) over a variable denotes percentage change. So Eq. (7.3) says that the percentage change in the exchange rate ![]() is equal to the percentage change in the domestic price level

is equal to the percentage change in the domestic price level ![]() minus the percentage change in the foreign price level

minus the percentage change in the foreign price level ![]() Therefore although absolute PPP states that the exchange rate is equal to the ratio of the price indexes, relative PPP deals with percentage changes in these variables.

Therefore although absolute PPP states that the exchange rate is equal to the ratio of the price indexes, relative PPP deals with percentage changes in these variables.

We usually refer to the percentage change in the price level as the rate of inflation. So another way of stating the relative PPP relationship is by saying that the percentage change in the exchange rate is equal to the inflation differential between the domestic and foreign country. If we say that the percentage change in the exchange rate is equal to the inflation differential, then we can ignore the actual levels of E, P, and PF and consider the changes, which is not so strong an assumption as absolute PPP. It should be noted that, if absolute PPP holds, then relative PPP will also hold. But if absolute PPP does not hold, relative PPP still may. This is so because the level of E may not equal P/PF, but the change in E could still equal the inflation differential.

Having observed in the preceding section how relative prices can determine exchange rates, we can, with reason, believe that over time these relative price changes will decrease in importance compared to inflation rates, so that in the long run inflation differentials will dominate exchange rate movements. The idea is that the real events that cause relative price movements are often random and short run in nature. By random, we mean they are unexpected and equally likely to raise or lower the exchange rate. Given this characterization, it follows that these random relative price movements will tend to cancel out over time (otherwise, we would not consider them equally likely to raise or lower E).

Time, Inflation, and PPP

Several researchers have found that PPP holds better for high-inflation countries. When we say “holds better,” we mean that the equalities stated in Eqs. (7.1) and (7.2) are more closely met by actual exchange rate and price level data observed over time in high-inflation countries compared to low-inflation countries. In high-inflation countries, changes in exchange rates are highly correlated with inflation differentials because the sheer magnitude of inflation overwhelms the relative price effects, whereas in low- or moderate-inflation countries the relative price effects dominate exchange rate movements and lead to discrepancies from PPP. In terms of our earlier example, when the elevator is moving faster (high inflation), the movement of the balls inside (relative prices) is less important; however, when the elevator is moving slowly (low inflation), the movement of the bouncing balls is quite important.

Besides the rate of inflation, the period of time analyzed has an effect on how well PPP holds. We expect PPP to hold better for annual data than for monthly data, since the longer time frame allows for more inflation. Thus random relative price effects are less important, and we find exchange rate changes closely related to inflation differentials. Using the elevator analogy, the longer the time frame analyzed, the farther the elevator moves, and the more the elevator moves, the less important will be the balls inside. This suggests that studies of PPP covering many years are more likely to yield evidence of PPP than studies based on a few years’ data.

The literature on PPP is voluminous and tends to confirm the conclusions we have made. Researchers have presented evidence that relative price shifts can have an important role in the short run, but over time the random nature of the relative price changes reduces the importance of these unrelated events. Investigations over long periods of time (100 years, for instance) have concluded that PPP holds better in the long run.

Deviations From PPP

So far, the discussion has included several reasons why deviations from PPP occur. When discussing the role of arbitrage in goods markets, it was said that the law of one price would not apply to differentiated products or products that are not traded internationally. Furthermore since international trade involves shipping goods across national borders, prices may differ because of shipping costs or tariffs. Relative price changes can also be a reason why PPP would hold better in the long run than the short run. Such relative price changes result from real economic events, like changing tastes, bad weather, or government policy. The Appendix A provides further details on how relative prices can affect the PPP.

Since consumers in different countries consume different goods, price indexes are not directly comparable internationally. We know that evaluating PPP between the United States and Japan using the US and Japanese consumer price indexes is weakened by the fact that the typical Japanese consumer buys a different basket of goods than the typical US consumer. In this case the law of one price could hold perfectly for individual goods, yet we would observe deviations from PPP using the consumer price index for Japan and the United States.

It is important to realize that PPP is not a theory of exchange rate determination. In other words inflation differentials do not cause exchange rate change. PPP is an equilibrium relationship between two endogenous variables. When we say that prices and exchange rates are endogenous, we mean that they are simultaneously determined by other factors. The other factors are called exogenous variables. Exogenous variables may change independently, as with bad weather or government policy. Given a change in an exogenous variable, as with poor weather and a consequent poor harvest, both prices and exchange rates will change. Deviations in measured PPP will occur if prices and exchange rates change at different speeds. Evidence suggests that following some exogenous shock, changes in exchange rates precede changes in prices.

Such a finding can be explained by theorizing that the price indexes used for PPP calculations move slowly because commodity prices are not as flexible as financial asset prices (the exchange rate is the price of monies). We know that exchange rates vary throughout the day as the demand and supply for foreign exchange vary. But how often does the department store change the price of furniture, or how often does the auto parts store change the price of tires? Since the prices that enter into published price indexes are slower to adjust than are exchange rates, it is not surprising that exchange rate changes seem to lead price changes. Yet if exchange rates change faster than goods prices, then we have another reason why PPP should hold better in the long run than in the short run. When economic news is received, both exchange rates and prices may change. For instance suppose the Federal Reserve announces today that it will promote a 100% increase in the US money supply over the next 12 months. Such a change would cause greater inflation because more money in circulation leads to higher prices. The dollar would also fall in value relative to other currencies because the supply of dollars rises relative to the demand.

Following the Fed’s announcement, would you expect goods prices in the United States to rise before the dollar depreciates on the foreign exchange market? While there are some important issues in exchange rate determination that must wait until later chapters, we generally can say here that the dollar would depreciate immediately following the announcement. If traders believe that the dollar will be worth less in the future, they will attempt to sell dollars now, and this selling activity drives down the dollar’s value today. There should be some similar forces at work in the goods market as traders expecting higher prices in the future buy more goods today. But for most goods, the immediate short-run result will be a depletion of inventories at constant prices. Only over time will most goods prices rise.

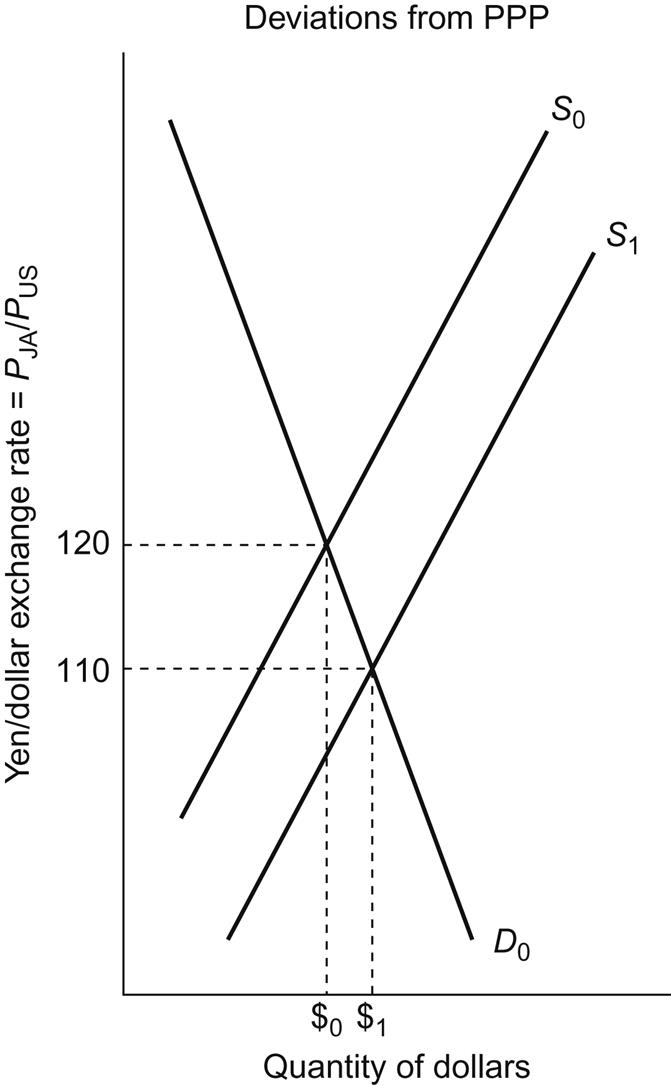

Fig. 7.2 illustrates how the exchange rate will shift with news. The figure illustrates the quantity of dollars bought and sold on the horizontal axis and the yen price of the dollar on the vertical axis. Initially the foreign exchange market equilibrium occurs where the demand curve, D0, intersects the supply curve, S0, at an exchange rate of 120 yen/dollar with quantity Q0 of dollars being bought and sold. Suppose the Federal Reserve now issues a statement causing people to expect the US money supply to grow more rapidly in the future. This causes foreign exchange traders to expect the dollar to depreciate in the future. As a result, they attempt to sell more dollars now, shifting the supply curve out to S1 in Fig. 7.2. This shift in supply, with constant demand, causes the dollar to depreciate down to 110 yen/dollar. At this new exchange rate, a quantity Q1 is traded.

Suppose initially PPP holds, so that E=120=PJA/PUS. The announced change in monetary policy has an immediate effect on the exchange rate because currencies are traded continuously throughout the day. Prices of goods and services will change much more slowly. In the short run the ratio of the price level in Japan to the price level in the United States may remain unchanged at 120. So while E falls today to 110 in Fig. 7.2, the ratio of the national price levels is still equal to the initial exchange rate of 120, and there is an apparent deviation from PPP.

Therefore periods with important economic news will be periods when PPP deviations are large—the exchange rate adjusts while prices lag behind. In addition to the differential speed of adjustment between exchange rates and prices, periods dominated by news are likely to be periods involving much relative price change, so that PPP deviations would tend to appear even without exchange rates and prices changing at different speeds.

Deviations from PPP are also likely because international trade involves lags between order and delivery. Prices are often set by contract today for goods that are to be delivered several months later. If we compare goods prices and exchange rates today to evaluate PPP, we are using the exchange rate applicable to goods delivered today with prices that were set some time in the past. Ideally we should compare contract prices in each country at the time contracts are signed with the exchange rate that is expected to prevail in the future period when goods are actually delivered and payment is made. If the exchange rate actually realized in the future period is the same as that expected when the goods prices were agreed upon, then there would be no problem in using today’s exchange rate and today’s delivered goods prices. The problem is that, realistically, exchange rates are very difficult to forecast, so that seldom would today’s realized exchange rate be equal to the trader’s forecast at some past period.

Let us consider a simple example. Suppose that on September 1, Mr. U.S. agrees to buy books from Ms. U.K. for £1 per book. At the time the contract is signed, books in the United States sell for $2, and the current exchange rate of E$/£=2 ensures that the law of one price holds—a £1 book from the United Kingdom is selling for the dollar equivalent of $2 (the pound book price of 1 times the dollar price of the pound of $2). If the contract calls for delivery and payment on December 1 of £1 per book and Mr. U.S. expects the exchange rate and prices to be unchanged until December 1, he expects PPP to hold at the time the payment is due. Suppose that on December 1, the actual exchange rate is £1=$1.50. An economist researching the law of one price for books would compare book prices of £1 and $2 with the exchange rate of E$/£=1.50, and examine if E$/£=PUS/PUK. Since 1.50<2/1, he would conclude that there are important deviations from PPP. Yet these deviations are spurious. At the time the prices were set, PPP was expected to hold. We generate the appearance of PPP deviations by comparing exchange rates today with prices that were set in the past.

The possible explanations for deviations from PPP include factors that would suggest permanent deviations (shipping costs and tariffs), factors that would produce temporary deviations (differential speed of adjustment between financial asset markets and goods markets, or real relative price changes), and factors that cause the appearance of deviations where none may actually exist (comparing current exchange rates with prices set in the past or using national price indexes when countries consume different baskets of goods). Since PPP measurements convey information regarding the relative purchasing power of currencies, such measurements have served as a basis for economic policy discussions. The next section will provide an example of policy-related information contained in PPP measurement.

Overvalued and Undervalued Currencies

If we observe E, P, and PF over time, we find that the absolute PPP relationship does not hold very well for any pair of countries. If, over time, PF rises faster than P, then we would expect E, the domestic currency price of the foreign currency, to fall. If E does not fall by the amount suggested by the lower P/PF, then we could say that the domestic currency is undervalued or (the same thing) that the foreign currency is overvalued.

In the early 1980s there was much talk of an overvalued dollar. The foreign exchange value of the dollar appeared to be too high relative to the inflation differentials between the United States and the other developed countries. The term overvalued suggests that the exchange rate is not where it should be yet. However, if the free-market supply and demand factors are determining the exchange rate, then the overvalued exchange rate is actually the free-market equilibrium rate. This means that the term overvalued might suggest that this equilibrium is merely a temporary deviation from PPP, and over time the exchange rate will fall in line with the inflation differential.

In the early 1980s the foreign exchange price of the dollar grew at a faster rate than the inflation differential between the other industrial nations and the United States. It appears, then, that for more than 4 years, a dollar overvaluation developed. Not until 1985 did the exchange rate begin to return to a level consistent with PPP. Fig. 7.3 illustrates the actual level of the yen/dollar exchange rate and the implied PPP exchange rate of the yen/dollar. The implied PPP exchange rate is measured by the inflation rate differential between Japan and the United States. The line labeled “PPP exchange rate” measures the values the exchange rate would take if the percentage change in the exchange rate equaled the inflation differential between Japan and the United States.

Fig. 7.3 shows that the dollar appears to be overvalued in the early 1980s, in that the actual exchange rate is above that implied by PPP as measured by inflation differentials. By 1985 the dollar begins to depreciate against the yen and move toward the PPP value of the exchange rate. In the 1990s the dollar becomes substantially undervalued, bottoming out in around the mid-1990s. However, by the end of 1990s the dollar value again returns to the PPP level. During the second half of the 2000s the yen/dollar exchange rate starts to dip below the implied PPP values, with the low point reached in early 2012. Then the dollar strengthens considerably and becomes overvalued in 2015.

Since we know that PPP does not hold well for any pair of countries with moderate inflation in the short run, we must always have currencies that appear overvalued or undervalued in a PPP sense. The issue becomes important when the apparent over- or undervaluation persists for some time and has significant macroeconomic consequences. In the early 1980s the United States political issue at the forefront of this apparent dilemma was that the overvalued dollar was hurting export-oriented industries. The US goods were rising in price to foreign buyers as the dollar appreciated. The problem was made visible by a large balance of trade deficit that became a major political issue. In 1985 intervention in the foreign exchange market by major central banks contributed to a dollar depreciation that reduced the PPP-implied dollar overvaluation.

Besides the dollar overvaluation relative to the other developed countries’ currencies, from time to time many developing countries have complained that their currencies are overvalued against the developed countries’ currencies, and thus their balance of trade sustains a larger deficit than would otherwise occur. If PPP applied only to internationally traded goods, then we could show how lower labor productivity in developing countries could contribute to apparently overvalued currencies. For nontraded goods we assume that production methods are similar worldwide. It may make more sense to think of the nontraded goods sector as being largely services. In this case more productive countries tend to have higher wages and thus higher prices in the service sector than less-productive, low-wage countries. We now have a situation in which the price indexes used to calculate PPP vary with productivity and hence with wages in each country.

If we assume that exchange rates are determined only by traded goods prices (the idea being that if a good does not enter into international trade, there is no reason for its price to be equalized internationally and thus no reason for changes in its price to affect the exchange rate), then we can find how price indexes vary with service prices while exchange rates are unaffected. For instance the price of a haircut in Paris should not be affected by an increase in haircut prices in Los Angeles. So if the price of haircuts should rise in Los Angeles, other things being equal, the average price level in the United States increases. But this US price increase should not have any impact on the dollar per euro exchange rate. If, instead, the price of an automobile rises in the United States relative to French auto prices, we would expect the dollar to depreciate relative to the euro because demand for French autos (and thus euros) increases while demand for US autos (and thus dollars) decreases.

If the world operates in the way just described, then we would expect that the greater are the traded goods productivity differentials between countries, the greater will be the wage differentials reflected in service prices, and thus the greater will be the deviations from absolute PPP over time. Suppose that developing countries, starting from lower absolute levels of productivity, have higher productivity growth rates. If per capita income differences between countries give a reasonable measure of the productivity differences, then we would anticipate that as developing country per capita income increases relative to developed country per capita income, the developing country price index will grow faster than that of the developed country. But at the same time, the depreciation of the developing country’s currency lags behind the inflation differentials, as measured by the average price levels in each country that include traded and nontraded goods prices. Thus, over time, the currency of the developing country will tend to appear overvalued (the foreign exchange value of the developing country’s money has not depreciated as much as called for by the movements in the average price levels), whereas the developed country’s currency will appear undervalued (the exchange value of the developed country’s money has not appreciated as much as the price level changes would indicate).

Does the preceding discussion describe the real world? Do you believe that labor-intensive services (domestic servants, haircuts, etc.) are cheaper in poorer countries than in wealthy countries? Researchers have provided evidence suggesting that the deviations from PPP as previously mentioned do indeed occur systematically with changes in per capita income.

What is the bottom line of the foregoing consideration? National price indexes are not particularly good indicators of the need for exchange rate adjustments. In this respect it is not surprising to find that many studies have shown that absolute PPP does not hold. The idea that currencies are undervalued or overvalued can be misleading if exchange rates are free to change with changing market conditions. Only if central bank or government intervention interrupts the free adjustment of the exchange rate to market clearing levels can we really talk about a currency as being overvalued or undervalued (and in many such instances black markets develop where the currency is traded at free-market prices). The fact that changes in PPP over time present the appearance of an undervalued currency in terms of the price indexes of two countries is perhaps more an indicator of the limitations of price indexes than of any real market phenomena.

Real Exchange Rates

All discussions of exchange rates so far have been with respect to the nominal exchange rate. This is the exchange rate that is actually observed in the foreign exchange market. However, economists sometimes utilize the concept of the real exchange rate to represent changes in the competitiveness of a currency. The real exchange rate is an alternative way to think about currencies being over- and undervalued. The real exchange rate is measured as

(7.4)

or the nominal exchange rate adjusted for the ratio of the home price level relative to the price level abroad. In Fig. 7.3 one sees that the dollar appeared to be significantly overvalued against the yen in the early 1980s and then significantly undervalued in the mid-1990s. In terms of real exchange rate changes, this would mean that the real exchange rate in terms of yen per dollar would have risen in the early 1980s as the nominal exchange rate (yen per dollar) rose relative to the ratio of Japanese prices to US prices. Then, in the 1990s, the real yen/dollar exchange rate fell as the nominal exchange rate decreased relative to the ratio of Japanese prices to US prices.

If absolute PPP always held, the real exchange rate would equal 1. In such a world nominal exchange rates would always change to mirror the change in the ratio of home prices to foreign prices. Since the real world has deviations from PPP, we also observe real exchange rates rising and falling. When the real exchange rate rises beyond some point, concern is expressed about an exchange rate overvaluation. When the real exchange rate falls beyond some point, concern is expressed about exchange rate undervaluation. As stated in the preceding section, terms like overvaluation and undervaluation must be used carefully. Such terms may sometimes reflect shortcomings of price indexes as inputs into measures of currency values.

Summary

1. PPP explains the relationship between product price levels and exchange rates.

2. If the exchange rate between two currencies is equal to the ratio of average price levels between two countries, then the absolute PPP holds.

3. If the percentage change in the exchange rate is equal to the inflation rate differential between two countries, then relative PPP holds.

4. PPP holds better for high-inflation countries due to the movement of price levels overwhelms any relative price changes.

5. From empirical evidence, exchange rates seem to deviate from PPP in the short run, but PPP tends to hold in the long run.

6. Deviations from PPP may arise from the presence of nontraded good prices in price indexes, differentiated goods, transactions costs, government restrictions, different consumption bundles in price indexes across countries, and adjustment lags between exchange rates and product prices.

7. A currency is overvalued (undervalued) if it has appreciated more (less) than the inflation rate differential between two countries as implied by PPP.

Exercises

1. Assume that the cost of a particular basket of goods is equal to $108 in the United States and ¥14,000 in Japan.

a. What should the ¥/$ exchange rate be according to absolute PPP?

b. If the actual exchange rate were equal to 120, would the dollar be considered undervalued or overvalued?

2. Suppose that the inflation rate in India is 100% and the inflation rate in the United States is 5%. According to relative PPP, what would happen to the value of dollar/rupee exchange rate?

3. If nontradable goods prices rise faster in country A than in country B, and tradable goods prices remain unchanged, determine whether currency A will appear to be overvalued or undervalued.

4. Explain why relative PPP may hold when absolute PPP does not?

5. List four reasons why deviations from PPP might occur; then carefully explain how each causes such deviations?

6. What is the “real exchange rate”? What does the real exchange rate equal if absolute PPP holds?

Appendix A The Effect on PPP by Relative Price Changes

Arbitrage in goods markets makes it easy to understand why price level changes affect exchange rates, but the effect of relative price changes is more subtle. The following example will illustrate how exchange rates can change because of relative price change even though there is no change in the overall price level (no inflation). Table 7.A summarizes the argument. Let us suppose there are two countries, France and Japan, and each consumes wine and sake. Initially, in period 0, wine and sake each sell for 1 euro in France and 1 yen in Japan. In a simple world of no transport costs or other barriers to the law of one price, the exchange rate, E=€/¥, must equal 1. Note that initially the relative price of one bottle of wine is equal to one bottle of sake (since sake and wine sell for the same price in each country). To determine the inflation rate in each country, we must calculate price indexes that indicate the value of the items consumed in each country for each period. Suppose that initially France consumes 9 units of wine and 1 unit of sake, whereas Japan consumes 1 wine and 9 sake. At the domestic prices of 1 unit of domestic currency per unit of wine or sake, we can see that the total value of the basket of goods consumed in France is 10 euros, whereas the total value of the goods consumed in Japan is 10 yen.

Table 7.A

The effect of a relative price change on the exchange rate

| France | ||||

| Period 0 | Period 1 | |||

| Price (in Euros) | Quantity consumed | Price (in Euros) | Quantity consumed | |

| Wine | 1 | 9 | 1.111 | 8 |

| Sake | 1 | 1 | 0.741 | 1.5 |

| Value of consumption | 10 | 10 | ||

| Japan | ||||

| Period 0 | Period 1 | |||

| Price (in Yen) | Quantity consumed | Price (in Yen) | Quantity consumed | |

| Wine | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.333 |

| Sake | 1 | 9 | 1 | 9.5 |

| Value of consumption | 10 | 10 | ||

Note: Exchange rate, €/¥, in period 0=1; exchange rate, €/¥, in period 1=0.741.

Source: Adapted from Solnik, B., 1978. International parity conditions and exchange risk. J. Banking Financ. 289.

Now let us suppose that there is a bad grape harvest, so that in the next period wine is more expensive. In terms of relative prices, we know that the bad harvest will make wine rise in price relative to sake. Suppose now that instead of the original relative price of 1 sake=1 wine, we now have 1.5 sake=1 wine. Consumers will recognize this change in relative prices and tend to decrease their consumption of wine and increase consumption of sake. Suppose in period 1 the French consume 8 wine and 1.5 sake, whereas the Japanese consume 0.333 wine and 9.5 sake. Let us further assume that the central banks of Japan and France follow a policy of zero inflation, where inflation is measured by the change in the cost of current consumption. With no inflation, the value of the consumption basket will be unchanged from period 0 and will equal 10 in each country. Thus although average prices have not changed, we know that individual prices must change because of the rising price of wine relative to sake.

The determination of the individual prices is a simple exercise in algebra, but is not needed to understand the central message of the example; therefore, students could skip this paragraph and still retain the benefit of the lesson. Since we know that France consumes 8 wine and 1.5 sake with a total value of 10 francs and that the relative price is 1.5 sake=1 wine, we can solve for the individual prices by letting 1.5Ps=Pw, and we can then substitute this into our total spending equation (8Pw+1.5Ps=10) to determine the prices. In other words we have a system with two equations and two unknowns that is solvable:

(7.A1)

(7.A2)

Substituting Eq. (7.A2) into the previous equation, we obtain

(7.A3)

Since Pw=1.111, we can use this to determine Ps:

(7.A4)

Thus we have our prices in France in period 1. For Japan it is even easier:

(7.A5)

(7.A6)

Substituting Eq. (7.A6) into the preceding equation, we obtain

(7.A7)

Thus

(7.A8)

Given the new prices in period 1, we can now determine the exchange rate implied by the law of one price. Since sake sells for 0.741 euros in France and 1 yen in Japan, the euro price of yen must be €/¥=0.741.

In summary this example has shown how exchange rates can change because of real economic events, even when average price levels are constant. Since PPP is usually discussed in terms of price indexes, we find that real events, such as the relative price changes brought about by a poor harvest, will cause deviations from absolute PPP as the exchange rate changes, even though the price indexes are constant. Note also that the relative price effect leads to an appreciation of the currency in the country where consumption of the good that is increasing in price is heaviest. In our example the euro appreciates as a result of the increased relative price of wine.