Classes exist in a hierarchy, and every class has exactly one superclass – except for the root class of the entire hierarchy: NSObject (Figure 2.8). A class inherits the behavior of its superclass, which means, at minimum, every class inherits the methods and instance variables defined in NSObject. As the top superclass, NSObject’s role is to implement the basic behavior of every object in Cocoa Touch. Two of the methods NSObject implements are alloc and description. (We sometimes say “description is a method on NSObject” and mean the same thing.)

A subclass can add methods and instance variables to extend the behavior of its superclass. For example, NSMutableArray extends NSArray’s ability to hold pointers to objects by adding the ability to dynamically add and remove objects.

A subclass can also override methods of its superclass. For example, NSString overrides the description method of NSObject. Sending the description message to an NSObject returns information about that instance. By default, description returns the object’s class and its address in memory, like this: <QuizAppDelegate: 0x4b222a0>.

A subclass of NSObject can override this method to return something that better describes an instance of that subclass. For example, NSString overrides description to return the string itself. NSArray overrides description to return the description of every object in the array.

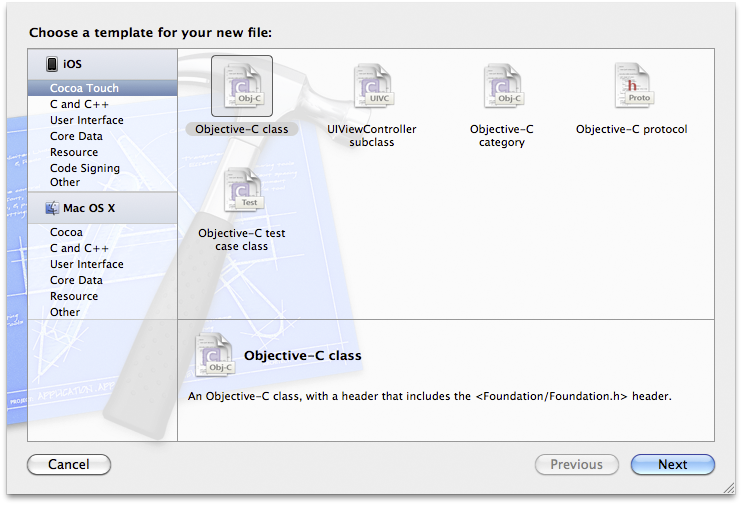

In this exercise, you’re going to create a subclass of NSObject named Possession. An instance of the Possession class will represent an item that a person owns in the real world. Click → → . Select Cocoa Touch from the iOS section in the lefthand table. Then select Objective-C class from the upper panel and hit Next, as shown in Figure 2.9.

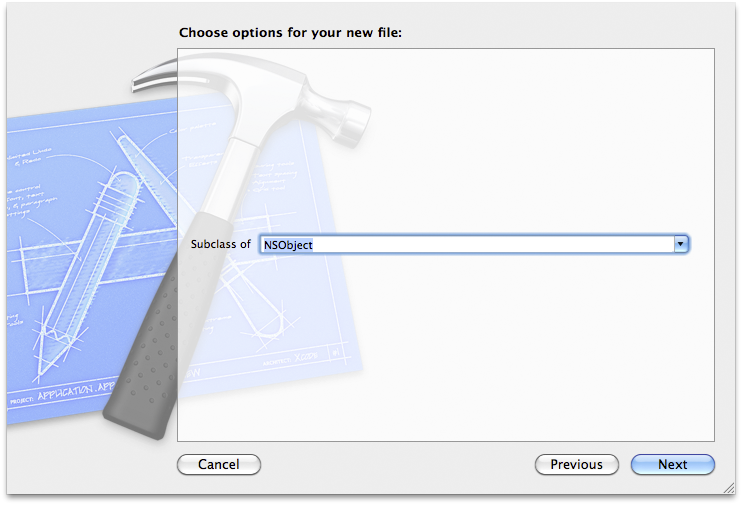

On the next panel, select NSObject as the superclass and click Next, as shown in Figure 2.10.

Name the class Possession (Figure 2.11). When creating a new class for a project, you want to save the files that describe it inside the project’s source directory on the filesystem. By default, the current project directory is already selected for you. You can also choose the group in the project navigator that these files will be added to. Because these groups are simply for organizing and because this project is very small, the group doesn’t matter, so just stick with the default. Make sure the checkbox is selected for the RandomPossessions target. This ensures that this class will be compiled when the project is built. Click Save.

Creating the Possession class generated two files: Possession.h and Possession.m. Locate those files in the project navigator. Possession.h is the header file (also called an interface file). This file declares the name of the new class, its superclass, the instance variables that each instance of this class has, and any methods this class implements. Possession.m is the implementation file, and it contains the code for the methods that the class implements. Every Objective-C class has these two files. You can think of the header file as a user manual for an instance of a class and the implementation file as the engineering details that define how it really works.

Open Possession.h in the editor area by clicking on it in the project navigator. The file currently looks like this:

#import <UIKit/UIKit.h>

@interface Possession : NSObject

{

}

@end

Let’s break down this interface declaration to figure out what it means. First, note that the C language retains all of its keywords, and any additional keywords added by Objective-C are distinguishable by the @ prefix. To declare a class in Objective-C, you use the keyword @interface followed by the name of this new class. After a colon comes the name of the superclass. Possession’s superclass is NSObject. Objective-C only allows single inheritance, so you will only ever see the following pattern:

@interface ClassName : SuperclassName

Next comes the space for declaring instance variables. Instance variables must be declared inside the curly brace block immediately following the class and superclass declaration. After the closing curly brace, you declare any methods that this class implements. Finally, the @end keyword finishes off the declaration for the new class.

So far, the Possession class doesn’t add anything to its superclass NSObject. What it needs are some possession-like instance variables. A possession, in our world, is going to have a name, a serial number, a value, and a date of creation. In Possession.h, add instance variables to the Possession class:

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

@interface Possession : NSObject

{

NSString *possessionName;

NSString *serialNumber;

int valueInDollars;

NSDate *dateCreated;

}

@end

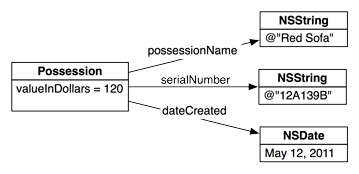

Now every instance of Possession has a spot for a simple integer. It also has spots to hold references to two NSString instances and one NSDate instance. (A reference is another word for pointer; the asterisk (*) denotes that the variable is a pointer.) Figure 2.12 shows an example of a Possession instance after its instance variables have been given values.

Notice that Figure 2.12 shows a total of four objects: the Possession, two NSStrings and the NSDate. Each of these objects is its own object and exists independently of the others. The Possession only has pointer to the three other objects. These pointers are the instance variables of Possession.

For example, every Possession has a pointer instance variable named possessionName. This Possession’s possessionName points to an NSString instance whose contents are “Red Sofa.” The “Red Sofa” string does not live inside the Possession, though. The Possession instance knows where the “Red Sofa” NSString lives in memory and stores its address as possessionName. One way to think of this relationship is “the Possession calls this string its possessionName. ”

The story is different for the instance variable valueInDollars. This instance variable is not a pointer to another object; it is just an int. Non-pointer instance variables are stored inside the object itself. This is not an easy idea to understand at first. Throughout this book, we will make use of object diagrams like this one to drive home the difference between an object and a pointer to an object.

Now that you have instance variables, you need a way to get and set their values. In object-oriented languages, we call methods that get and set instance variables accessors. Individually, we call them getters and setters. Without these methods, one object cannot access the instance variables of another object.

Accessor methods look like this:

// Getter

- (NSString *)possessionName

{

// Return a pointer to the object this Possession calls its possessionName

return possessionName;

}

// Setter

- (void)setPossessionName:(NSString *)newPossessionName

{

// Change the instance variable to point at another string,

// this Possession will now call this new string its possessionName

possessionName = newPossessionName;

}

Then, if you wanted to access a Possession’s possessionName, you would send it one of the following messages:

// Create a new Possession instance Possession *p = [[Possession alloc] init]; // Set possessionName to a new NSString [p setPossessionName:@"Red Sofa"]; // Get the pointer of the Possession's possessionName NSString *str = [p possessionName]; // Print that object NSLog(@"%@", str); // This would print "Red Sofa"

In Objective-C, the name of a setter method is set plus the name of the instance variable it is changing – in this case, setPossessionName:. In other languages, the name of the getter method would likely be getPossessionName. However, in Objective-C, the name of the getter method is just the name of the instance variable. Some of the cooler parts of the Cocoa Touch library make the assumption that your classes follow this convention; therefore, stylish Cocoa Touch programmers always do so.

In Possession.h, declare accessor methods for the instance variables of Possession. You will need getters and setters for valueInDollars, possessionName, and serialNumber. For dateCreated, you only need a getter method.

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

@interface Possession : NSObject

{

NSString *possessionName;

NSString *serialNumber;

int valueInDollars;

NSDate *dateCreated;

}

- (void)setPossessionName:(NSString *)str;

- (NSString *)possessionName;

- (void)setSerialNumber:(NSString *)str;

- (NSString *)serialNumber;

- (void)setValueInDollars:(int)i;

- (int)valueInDollars;

- (NSDate *)dateCreated;

@end

(For those of you with some experience in Objective-C, we’ll talk about properties in the next chapter.)

Now that these accessors have been declared, they need to be defined in the implementation file. Open Possession.m in the editor area by selecting it in the project navigator.

At the top of any implementation file, you must import the header file of that class. The implementation of a class needs to know how it has been declared. (Importing a file is the same as including a file in the C language except you are ensured that the file will only be included once.)

After the import statements is an implementation block that begins with the @implementation keyword followed by the name of the class that is being implemented. All of the method definitions in the implementation file are inside this implementation block. Methods are defined until you close out the block with the @end keyword.

We’re going to skip memory management until the next chapter, so the accessor methods for Possession are very simple: setter methods assign the appropriate instance variable to point at the incoming object, and getter methods return a pointer to the object the instance variable points at. (For valueInDollars, we’re just assigning the passed-in value to the instance variable for the setter and returning the value in the getter.) Edit Possession.m:

#import "Possession.h"

@implementation Possession

- (void)setPossessionName:(NSString *)str

{

possessionName = str;

}

- (NSString *)possessionName

{

return possessionName;

}

- (void)setSerialNumber:(NSString *)str

{

serialNumber = str;

}

- (NSString *)serialNumber

{

return serialNumber;

}

- (void)setValueInDollars:(int)i

{

valueInDollars = i;

}

- (int)valueInDollars

{

return valueInDollars;

}

- (NSDate *)dateCreated

{

return dateCreated;

}

@end

Build your application (select → or use the shortcut Command-B) to ensure that there are no compiler errors or warnings.

Now that your accessors have been declared and defined, you can send messages to Possession instances to get and set their instance variables. Let’s test this out. In main.m, import the header file for Possession and create a new Possession instance. After it is created, log its instance variables to the console.

#import "Possession.h"

int main (int argc, const char * argv[])

{

NSAutoreleasePool *pool = [[NSAutoreleasePool alloc] init];

NSMutableArray *items = [[NSMutableArray alloc] init];

[items addObject:@"One"];

[items addObject:@"Two"];

[items addObject:@"Three"];

[items insertObject:@"Zero" atIndex:0];

for(int i = 0; i < [items count]; i++) {

NSLog(@"%@", [items objectAtIndex:i]);

}

Possession *p = [[Possession alloc] init];

NSLog(@"%@ %@ %@ %d", [p possessionName], [p dateCreated],

[p serialNumber], [p valueInDollars]);

[items release];

items = nil;

[pool drain];

return 0;

}

Build and run the application. Check the console by selecting the most recent entry in the log navigator. You should see the previous console output followed by a line that has three “(null)” strings and a 0. (When an object is created, all of its instance variables are set to 0. For primitives like int, the value is 0; for pointers to objects, that pointer points to nil.)

To give this Possession some substance, you need to create new objects and pass them as arguments to the setter methods for this instance. In main.m, type in the following code:

// Notice we omitted some of the surrounding code. The bold code is the code to add, // the non-bold code is existing code that shows you where to type in the new stuff. Possession *p = [[Possession alloc] init]; // This creates a new NSString, "Red Sofa", and gives it to the Possession [p setPossessionName:@"Red Sofa"]; // This creates a new NSString, "A1B2C", and gives it to the Possession [p setSerialNumber:@"A1B2C"]; // We send the value 100 to be used as the valueInDollars of this Possession [p setValueInDollars:100]; NSLog(@"%@ %@ %@ %d", [p possessionName], [p dateCreated], [p serialNumber], [p valueInDollars]);

Build and run the application. Now you should see values for everything but the dateCreated, which we’ll take care of shortly.

Not all instance methods are accessors. You will regularly find yourself wanting to send messages to instances that perform other tasks. One such message is description. You can implement this method for Possession to return a string that describes a Possession instance. Because Possession is a subclass of NSObject (the class that originally declares the description method), when you re-implement this method in the Possession class, you are overriding it. When overriding a method, all you need to do is define it in the implementation file; you do not need to declare it in the header file because it has already been declared by the superclass.

In Possession.m, override the description method. This new code can go anywhere between @implementation and @end, as long as it’s not inside the curly brackets of an existing method.

- (NSString *)description

{

NSString *descriptionString =

[[NSString alloc] initWithFormat:@"%@ (%@): Worth $%d, recorded on %@",

possessionName,

serialNumber,

valueInDollars,

dateCreated];

return descriptionString;

}

Now whenever you send the message description to an instance of Possession, it will return an NSString that describes that instance. (To those of you familiar with Objective-C and managing memory, don’t panic – you will fix the problem with this code in the next chapter.) In main.m, substitute this new method into the NSLog that prints out the instance variables of the Possession.

[p setValueInDollars:100]; // Remember, an NSLog with %@ as the token will print the // description of the corresponding argument NSLog(@"%@", p);

Build and run the application and check your results in the log navigator. You should see a log statement that looks like this:

Red Sofa (A1B2C): Worth $100, recorded on (null)

What if you want to create an entirely new instance method, one that you are not overriding from the superclass? You declare the new method in the header file and define it in the implementation file. A good method to begin with is an object’s initializer.

At the beginning of this chapter, we discussed how an instance is created: its class is sent the message alloc, which creates an instance of that class and returns a pointer to it, and then that instance is sent the message init, which gives its instance variables initial values. As you start to write more complicated classes, you will want to create initialization methods like init that take arguments that the object can use to initialize itself. For example, the Possession class would be much cleaner if we could pass one or more of its variables as part of the initialization process.

To cover the different possible initialization scenarios, many classes have more than one initialization method, or initializer. Each initializer begins with the word init. Naming initializers this way doesn’t make these methods different from other instance methods; it is only a naming convention. However, the Objective-C community is all about naming conventions, which you should strictly adhere to. (Seriously. Disregarding naming conventions in Objective-C results in problems that are worse than most beginners would imagine.)

For each class, regardless of how many initialization methods there are, one method is chosen as the designated initializer. For NSObject, there is only one initializer, init, so it is the designated initializer. The designated initializer makes sure that every instance variable of an object is valid. (“Valid” has different meanings, but in this context it means “when you send messages to this object after initializing it, you can predict the outcome and nothing bad will happen.”)

Typically, the designated initializer has parameters for the most important and frequently used instance variables of an object.

The Possession class has four instance variables, but only three are writeable. Therefore, Possession’s designated initializer needs to accept three arguments. In Possession.h, declare the designated initializer:

NSDate *dateCreated; } - (id)initWithPossessionName:(NSString *)name valueInDollars:(int)value serialNumber:(NSString *)sNumber; - (void)setPossessionName:(NSString *)str;

This method’s name, or selector, is initWithPossessionName:valueInDollars:serialNumber:. This selector has three labels (initWithPossessionName:, valueInDollars:, and serialNumber:), which tells you the method accepts three arguments.

These arguments each have a type and a parameter name. In the declaration, the type follows the label in parentheses. The parameter name then follows the type. So the label initWithPossessionName: is expecting a pointer to an instance of type NSString. Within the body of that method, you can use name to reference the NSString object pointed to.

Take another look at the initializer’s declaration. Its return type is id, which is defined as “a pointer to any object.” (This is a lot like void * in C and is pronounced “eye-dee.”) init methods are always declared to return id.

Why not make the return type Possession * – a pointer to a Possession? After all, that is the type of object that is returned from this method. A problem will arise, however, if Possession is ever subclassed. The subclass would inherit all of the methods from Possession, including this initializer and its return type. An instance of the subclass could then be sent this initializer message, but what would be returned? Not a Possession, but an instance of the subclass. You might think, “No problem. Override the initializer in the subclass to change the return type.” But remember – in Objective-C, you cannot have two methods with the same selector and different return types (or arguments). By specifying that an initialization method returns “any object,” we never have to worry what happens with a subclass.

As programmers, we always know the type of the object that is returned from an initializer. (How do we know this? It is an instance of the class we sent alloc to.) Not only do we know the type of the object, the object itself knows its type.

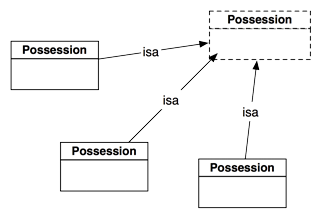

Every object has an instance variable called isa. When an instance is created by sending alloc to a class, that class sets the isa instance variable of the returned object to point back at the class that created it (Figure 2.13). We call it the isa pointer because an object “is a” instance of that class.

The isa pointer is where Objective-C holds much of its power. At runtime, when a message is sent to an object, that object goes to the class named in its isa pointer and says, “I was sent this message. Run the code for the matching method.” This is different than most compiled languages, where the method to be executed is determined at compile time.

Now that you have declared the designated initializer in Possession.h, you need to implement it. Open Possession.m. Recall that the definitions for methods go within the implementation block in the implementation file, and add the designated initializer there.

@implementation Possession

- (id)initWithPossessionName:(NSString *)name

valueInDollars:(int)value

serialNumber:(NSString *)sNumber

{

// Call the superclass's designated initializer

[super init];

// Give the instance variables initial values

[self setPossessionName:name];

[self setSerialNumber:sNumber];

[self setValueInDollars:value];

dateCreated = [[NSDate alloc] init];

// Return the address of the newly initialized object

return self;

}

In the designated initializer, the first thing you always do is call the superclass’s designated initializer using super. The last thing you do is return a pointer to the successfully initialized object using self. So to understand what’s going on in an initializer, you will need to know about self and super.

Inside a method, self is an implicit local variable. There is no need to declare it, and it is automatically set to point to the object that was sent the message. (Most object-oriented languages have this concept, but some call it this instead of self.) Typically, self is used so that an object can send a message to itself:

- (void)chickenDance

{

[self pretendHandsAreBeaks];

[self flapWings];

[self shakeTailFeathers];

}

In the last line of an init method, you always return the newly initialized object, so the caller can assign it to a variable:

return self;

Often when you are overriding a method in a subclass, you want it to add something to what the existing method of the superclass already does. To make this easier, there is a compiler directive in Objective-C called super:

- (void)someMethod

{

[self doMoreStuff];

[super someMethod];

}

How does super work? Usually when you send a message to an object, the search for a method of that name starts in the object’s class. If there is no such method, the search continues in the superclass of the object. The search will continue up the inheritance hierarchy until a suitable method is found. (If it gets to the top of the hierarchy and no method is found, an exception is thrown.) When you send a message to super, you are sending a message to self but demanding that the search for the method begin at the superclass.

In the case of Possession’s designated initializer, we send the init message to super. This calls NSObject’s implementation of init. If an initializer message fails, it will return nil. Therefore, it is a good idea to save the return value of the superclass’s initializer into the self variable and confirm that it is not nil before doing any further initialization. In Possession.m, edit your designated initializer to confirm the initialization of the superclass.

- (id)initWithPossessionName:(NSString *)name

valueInDollars:(int)value

serialNumber:(NSString *)sNumber

{

// Call the superclass's designated initializer

self = [super init];

// Did the superclass's designated initializer succeed?

if (self) {

// Give the instance variables initial values

[self setPossessionName:name];

[self setSerialNumber:sNumber];

[self setValueInDollars:value];

dateCreated = [[NSDate alloc] init];

}

// Return the address of the newly initialized object

return self;

}

A class can have more than one initializer. For example, Possession could have an initializer that takes an NSString for the possessionName, but not the serialNumber or valueInDollars. Instead of replicating all of the code in the designated initializer, this other initializer would simply call the designated initializer. It would pass the information it was given for the possessionName and pass default values for the other two arguments.

Possession’s designated initializer is initWithPossessionName:valueInDollars:serialNumber:. However, it has another initializer, init, that it inherits it from its superclass NSObject. If init is sent to an instance of Possession, none of the stuff you put in the designated initializer will be called. Therefore, you must link Possession’s implementation of init to its designated initializer. In Possession.m, override the init method to call the designated initializer with default values.

- (id)init

{

return [self initWithPossessionName:@"Possession"

valueInDollars:0

serialNumber:@""];

}

Using initializers as a chain like this reduces the chance for error and makes maintaining code easier. For classes that have more than one initializer, the programmer who created the class chooses which initializer is designated. You only write the core of the initializer once in the designated initializer, and other initialization methods simply call that core with default values. This relationship is shown in Figure 2.14; the designated initializers are white, and the additional initializer is gray.

Let’s form some simple rules for initializers from these ideas.

- A class inherits all initializers from its superclass and can add as many as it wants for its own purposes.

- Each class picks one initializer as its designated initializer.

- The designated initializer calls the superclass’s designated initializer.

- Any other initializer a class has calls the class’s designated initializer.

- If a class declares a designated initializer that is different from its superclass, you must override the superclass’ designated initializer to call the new designated initializer.

Methods come in two flavors: instance methods and class methods. Instance methods (like init) are sent to instances of the class, and class methods (like alloc) are sent to the class itself. Class methods typically either create new instances of the class or retrieve some global property of the class. Class methods do not operate on an instance or have any access to instance variables.

Syntactically, class methods differ from instance methods by the first character in their declaration. An instance method uses the - character just before the return type, and a class method uses the + character.

One common use for class methods is to provide convenient ways to create instances of that class. For the Possession class, it would be nice if you could create a random possession so that you could easily test your class without having to think up a bunch of clever names. Declare a class method in Possession.h that will create a random possession.

@interface Possession : NSObject

{

NSString *possessionName;

NSString *serialNumber;

int valueInDollars;

NSDate *dateCreated;

}

+ (id)randomPossession;

- (id)initWithPossessionName:(NSString *)name

valueInDollars:(int)value

serialNumber:(NSString *)sNumber;

Notice the order of the declarations for the methods. Class methods come first, followed by initializers, followed by any other methods. This is a convention that makes your header files easier to read.

Class methods that return an instance of their type create an instance (with alloc and init), configure it, and then return it. In Possession.m, implement randomPossession to create, configure, and return a Possession instance (make sure this method is between the @implementation and @end):

+ (id)randomPossession

{

// Create an array of three adjectives

NSArray *randomAdjectiveList = [NSArray arrayWithObjects:@"Fluffy",

@"Rusty",

@"Shiny", nil];

// Create an array of three nouns

NSArray *randomNounList = [NSArray arrayWithObjects:@"Bear",

@"Spork",

@"Mac", nil];

// Get the index of a random adjective/noun from the lists

// Note: The % operator, called the modulo operator, gives

// you the remainder. So adjectiveIndex is a random number

// from 0 to 2 inclusive.

int adjectiveIndex = rand() % [randomAdjectiveList count];

int nounIndex = rand() % [randomNounList count];

NSString *randomName = [NSString stringWithFormat:@"%@ %@",

[randomAdjectiveList objectAtIndex:adjectiveIndex],

[randomNounList objectAtIndex:nounIndex]];

int randomValue = rand() % 100;

NSString *randomSerialNumber = [NSString stringWithFormat:@"%c%c%c%c%c",

'0' + rand() % 10,

'A' + rand() % 26,

'0' + rand() % 10,

'A' + rand() % 26,

'0' + rand() % 10];

// Once again, ignore the memory problems with this method

Possession *newPossession =

[[self alloc] initWithPossessionName:randomName

valueInDollars:randomValue

serialNumber:randomSerialNumber];

return newPossession;

}

This method creates two arrays using the method arrayWithObjects:. arrayWithObjects: takes a list of objects terminated by nil. nil is not added to the array; it just indicates the end of the argument list.

Then randomPossession creates a string from a random adjective and noun, another string from random numbers and letters, and a random integer value. It then creates an instance of Possession and sends it the designated initializer with these randomly-created objects and int as parameters.

In this method, you also use stringWithFormat:, which is a class method of NSString. This message is sent directly to NSString, and the method returns an NSString instance with the passed-in parameters. In Objective-C, class methods that return an object of their type (like stringWithFormat: and randomPossession) are called convenience methods.

Notice the use of self in randomPossession. Because randomPossession is a class method, self refers to the Possession class itself instead of an instance. Class methods should use self in convenience methods instead of their class name so that a subclass can be sent the same message. In this case, if you create a subclass of Possession, you can send that subclass the message randomPossession. Using self (instead of Possession) will allocate an instance of the class that was sent the message and set the instance’s isa pointer to that class as well.

Open main.m. Currently, in the main function, you are adding NSString instances to an NSMutableArray instance and then printing them to the console. Now you will add Possession instances to the array and log them instead. Delete the code that previously created a single Possession and change your main function to look just like this:

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

#import "Possession.h"

int main (int argc, const char * argv[])

{

NSAutoreleasePool * pool = [[NSAutoreleasePool alloc] init];

NSMutableArray *items = [[NSMutableArray alloc] init];

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

Possession *p = [Possession randomPossession];

[items addObject:p];

}

for (int i = 0; i < [items count]; i++) {

NSLog(@"%@", [items objectAtIndex:i]);

}

[items release];

items = nil;

[pool drain];

return 0;

}

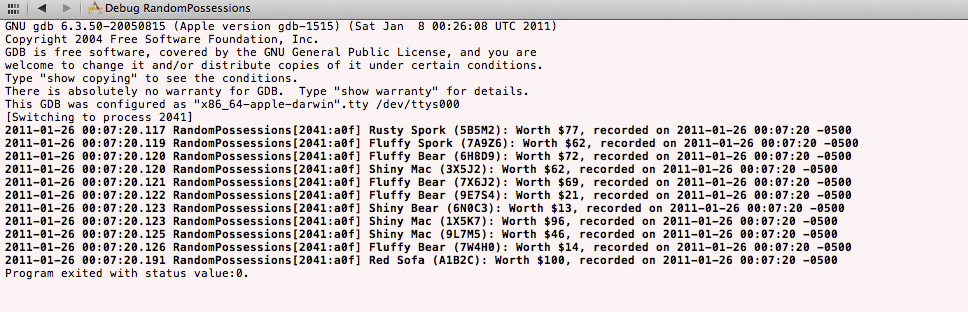

Build and run your application and then check the output in the log navigator. All you did was replace what objects you added to the array, and the code runs perfectly fine with a different output (Figure 2.15). Creating this class was a success.

Check out the #import statements at the top of main.m. Why did you have to import the class header Possession.h when you didn’t you have to import, say, NSMutableArray.h? NSMutableArray comes from the Foundation framework, so it is included when you import Foundation/Foundation.h. On the other hand, your class exists in its own file, so you have to explicitly import it into main.m. Otherwise, the compiler won’t know it exists and will complain loudly.