Chapter 2. The Energy Balance

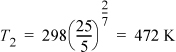

When you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it. When you cannot measure it, your knowledge is meager and unsatisfactory.

Lord Kelvin

The energy balance is based on the postulate of conservation of energy in the universe. This postulate is known as the first law of thermodynamics. It is a “law” in the same sense as Newton’s laws. It is not refuted by experimental observations within a broadly defined range of conditions, but there is no mathematical proof of its validity. Derived from experimental observation, it quantitatively accounts for energy transformations (heat, work, kinetic, potential). We take the first law as a starting point, a postulate at the macroscopic level, although the conservation of energy in elastic collisions does suggest this inference in the absence of radiation. Facility with computation of energy transformations is a necessary step in developing an understanding of elementary thermodynamics. The first law relates work, heat, and flow to the internal energy, kinetic energy, and potential energy of the system. Therefore, we precede the introduction of the first law with discussion of work and heat.

Chapter Objectives: You Should Be Able to...

1. Explain why enthalpy is a convenient property to define and tabulate.

2. Explain the importance of assuming reversibility in making engineering calculations of work.

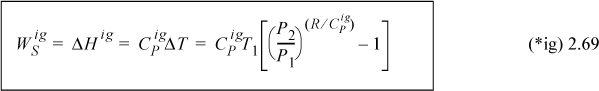

3. Calculate work and heat flow for an ideal gas along the following pathways: isothermal, isochoric, adiabatic.

4. Simplify the general energy balance for problems similar to the homework problems, textbook examples, and practice problems.

5. Properly use heat capacity polynomials and latent heats to calculate changes in U, H for ideal gases and condensed phases.

6. Calculate ideal gas or liquid properties relative to an ideal gas or liquid reference state, using the ideal gas law for the vapor phase properties and heats of vaporization.

2.1. Expansion/Contraction Work

There is a simple way that a force on a surface may interact with the system to cause expansion/contraction of the system in volume. This is the type of surface interaction that occurs if we release the latch of a piston, and move the piston in/out while holding the cylinder in a fixed location. Note that a moving boundary is not sufficient to distinguish this type of work—there must be movement of the system boundaries relative to one another. For expansion/contraction interactions, the size of the system must change. This distinction becomes significant when we contrast expansion/contraction work to flow work in Section 2.3.

How can we relate this amount of work to other quantities that are easily measured, like volume and pressure? For a force applied in the x direction, the work done on our system is

dW = Fapplied dx = –Fsystem dx

where we have used Newton’s principle of equal and opposite forces acting on a boundary to relate the applied and system forces. Since it is more convenient to use the system force in calculations, we use the latter form, and drop the subscript with the understanding that we are calculating the work done on the system and basing the calculation on the system force. For a constant force, we may write

W = – FΔx

If F is changing as a function of x then we must use an integral of F,

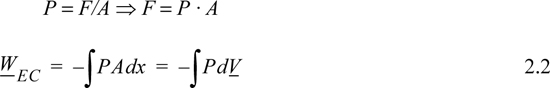

For a fluid acting on a surface of constant area A, the system force and pressure are related,

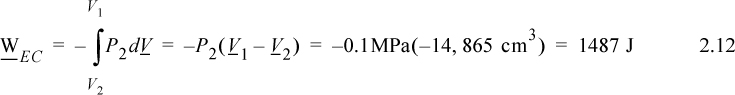

where the subscript EC refers to expansion/contraction work.

In evaluating this expression, a nagging question of perspective comes up. It would be a trivial question except that it causes major headaches when we later try to keep track of positive and negative signs. The question is essentially this: In the discussion above, is positive work being done on the system, or is negative work being done by the system? When we add energy to the system, we consider it a positive input into the system; therefore, putting work into the system should also be considered as a positive input. On the other hand, when a system does work, the energy should go down, and it might be convenient to express work done by the system as positive. The problem is that both perspectives are equally valid—therefore, the choice is arbitrary. Since various textbooks choose differently, there is always confusion about sign conventions. The best we can hope for is to be consistent during our own discussions. We hereby consider work to be positive when performed on the system. Thus, energy put into the system is positive. Because volume decreases when performing work of compression, the sign on the integral for work is negative,

where P and V are of the system. Clarification of “reversible” is given in Section 2.4 on page 42. By comparing Eqn. 2.3 with the definitions of work given by Eqns. 2.1 and 2.2, it should be obvious that the dV term results from expansion/contraction of the boundary of the system. The P results from the force of the system acting at the boundary. Therefore, to use Eqn. 2.3, the pressure in the integral is the pressure of the system at the boundary, and the boundary must move. A system which does not have an expanding/contracting boundary does not have expansion/contraction work.1

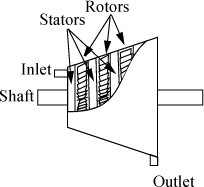

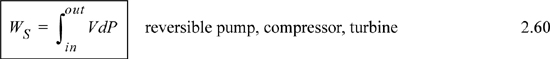

2.2. Shaft Work

In a flowing system, we know that a propeller-type device can be used to push a fluid through pipes—this is the basis of a centrifugal pump. Also, a fluid flowing through a similar device could cause movement of a shaft—this is the basis for hydroelectric power generation and the water wheels that powered mills in the early twentieth century. These are the most commonly encountered forms of shaft work in thermodynamics, but there is another slight variation. Suppose an impeller was inserted into a cylinder containing cookie batter and stirred while holding the piston at a fixed volume. We would be putting work into the cylinder, but the system boundaries would neither expand nor contract. All of these cases exemplify shaft work. The essential feature of shaft work is that work is being added or removed without a change in volume of the system. We show in Section 2.8, page 54, that shaft work for a reversible flow process can be computed from

Note that Eqns. 2.3 and 2.4 are distinct and should not be interchanged. Eqn. 2.4 is restricted to shaft work in an open system and Eqn. 2.3 is for expansion/contraction work in a closed system. We later show how selection of the system boundary in a flow system relates the two types of terms on page 54.

2.3. Work Associated with Flow

In engineering applications, most problems involve flowing systems. This means that materials typically flow into a piece of equipment and then flow out of it, crossing well-defined system boundaries in the process. Thus, we need to introduce an additional characterization of work: the work interaction of the system and surroundings when mass crosses a boundary. For example, when a gas is released out of a tank through a valve, the exiting gas pushes the surrounding fluid, doing work on the surroundings. Likewise, when a tank valve is opened to allow gas from a higher pressure source to flow inward, the surroundings do work on the gas already in the system. We calculate the work in these situations most easily by first calculating the rate at which work is done.

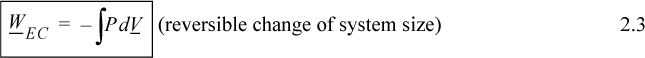

Let us first consider a fluid entering a system as shown in Fig. 2.1. We have dW = Fdx, and the work interaction of the system is positive since we are pushing fluid into the system. The rate of work is ![]() , but

, but ![]() is velocity, and F = P·A. Further rearranging, recognizing

is velocity, and F = P·A. Further rearranging, recognizing ![]() , and that the volumetric flow rate may be related to the mass specific volume and the mass flow rate,

, and that the volumetric flow rate may be related to the mass specific volume and the mass flow rate, ![]() ,

,

Figure 2.1. Schematic illustration of flow work.

where PV are the properties of the fluid at the point where it crosses the boundary, and ![]() is the absolute value of the mass flow rate across the boundary. When fluid flows out of the system, work is done on the surroundings and the work interaction of the system is

is the absolute value of the mass flow rate across the boundary. When fluid flows out of the system, work is done on the surroundings and the work interaction of the system is

where ![]() is the absolute value of the mass flow across the boundary, and since work is being done on the surroundings, the work interaction of the system is negative. When flow occurs both in and out, the net flow work is the difference:

is the absolute value of the mass flow across the boundary, and since work is being done on the surroundings, the work interaction of the system is negative. When flow occurs both in and out, the net flow work is the difference:

where ![]() and

and ![]() are absolute values of the mass flow rates. For more streams, we simply follow the conventions established, and add inlet streams and subtract outlet streams.

are absolute values of the mass flow rates. For more streams, we simply follow the conventions established, and add inlet streams and subtract outlet streams.

2.4. Lost Work versus Reversibility

In order to properly understand the various characteristic forms that work may assume, we must address an issue which primarily belongs to the upcoming chapter on entropy. The problem is that the generation of disorder reflected by entropy change results in conversion of potentially useful work energy into practically useless thermal energy. If “generation of disorder results in lost work,” then operating in a disorderly fashion results in the lost capability to perform useful work, which we abbreviate by the term: “lost work.” It turns out that the most orderly manner of operating is a hypothetical process known as a reversible process. Typically, this hypothetical, reversible process is applied as an initial approximation of the real process, and then a correction factor is applied to estimate the results for the actual process. It was not mentioned in the discussion of expansion/contraction work, but we implicitly assumed that the process was performed reversibly, so that all of the work on the system was stored in a potentially useful form. To see that this might not always be the case, and how this observation relates to the term “reversible,” consider the problem of stirring cookie batter. Does the cookie batter become unmixed if you stir in the reverse direction? Of course not. The shaft work of stirring has been degraded to effect the randomness of the ingredients. It is impossible to completely recover the work lost in the randomness of this irreversible process. Any real process involves some degree of stirring or mixing, so lost work cannot be eliminated, but we can hope to minimize unnecessary losses if we understand the issue properly.

Consider a process involving gas enclosed in a piston and cylinder. Let the piston be oriented upward so that an expansion of the gas causes the piston to move upward. Suppose that the pressure in the piston is great enough to cause the piston to move upward when the latch is released. How can the process be carried out so that the expansion process yields the maximum work? First, we know that we must eliminate friction to obtain the maximum movement of the piston.

Friction decreases the work available from a process. Frequently we neglect friction to perform a calculation of maximum work.

If we neglect friction, what will happen when we release the latch? The forces are not balanced. Let us take z as our coordinate in the vertical direction, with increasing values in the upward direction. The forces downward on the piston are the force of atmospheric pressure (–Patm · A, where A is the cross-sectional area of the piston) and the force of gravity (–m·g). These forces will be constant throughout movement of the piston. The upward force is the force exerted by the gas (P · A). Since the forces are not balanced, the piston will begin to accelerate upward (F = ma). It will continue to accelerate until the forces become balanced.2 However, when the forces are balanced, the piston will have a non-zero velocity. As it continues to move up, the pressure inside the piston continues to fall, making the upward force due to the inside pressure smaller than the downward force. This causes the piston to decelerate until it eventually stops. However, when it stops at the top of the travel, it is still not in equilibrium because the forces are again not balanced. It begins to move downward. In fact, in the absence of dissipative mechanisms we have set up a perpetual motion.3 A reversible piston would oscillate continuously between the initial state and the state at the top of travel. This would not happen in a real system. One phenomenon which we have failed to consider is viscous dissipation (the effect of viscosity).

Let us consider how velocity gradients dissipate linear motion. Consider two diatomic molecules touching one another which both have exactly the same velocity and are traveling in exactly the same direction. Suppose that neither is rotating. They will continue to travel in this direction at the same velocity until they interact with an external body. Now consider the same two molecules in contact, again moving in exactly the same direction, but one moving slightly faster. Now there is a velocity gradient. Since they are touching one another, the fact that one is moving a little faster than the other causes one to begin to rotate clockwise and the other counter-clockwise because of friction as one tries to move faster than the other. Naturally, the kinetic energy of the molecules will stay constant, but the directional velocities are being converted to rotational (directionless) energies. This is an example of viscous dissipation in a shear situation. In the case of the oscillating piston, the viscous dissipation prevents complete transfer of the internal energy of the gas to the piston during expansion, resulting in a stroke that is shorter than a reversible stroke. During compression, viscous dissipation results in a fixed internal energy rise for a shorter stroke than a reversible process. In both expansion and compression, the temperature of the gas at the end of each stroke is higher than it would be for a reversible stroke, and each stroke becomes successively shorter.

Velocity gradients lead to dissipation of directional motion (kinetic energy) into random motion (internal energy) due to the viscosity of a fluid. Frequently, we neglect viscous dissipation to calculate maximum work. A fluid would need to have zero viscosity for this mechanism of dissipation to be non-existent. Pressure gradients within a viscous fluid lead to velocity gradients; thus, one type of gradient is associated with the other.

We can see that friction and viscosity play an important role in the loss of capability to perform useful work in real systems. In our example, these forces cause the oscillations to decrease somewhat with each cycle until the piston comes to rest. Another possibility of motion that might occur with a piston is interaction with a stop, which limits the travel of the piston. As the piston travels upward, if it hits the stop, it will have kinetic energy which must be absorbed. In a real system, this kinetic energy is converted to internal energy of the piston, cylinder, and gas.

Kinetic energy is dissipated to internal energy when objects collide inelastically, such as when a moving piston strikes a stop. Frequently we imagine systems where the cylinder and piston can neither absorb nor transmit heat; therefore, the lost kinetic energy is returned to the gas as internal energy.

So far, we have identified three dissipative mechanisms. Additional mechanisms are diffusion along a concentration gradient and heat conduction along a temperature gradient, which will be discussed in Chapter 4. Velocity, temperature, and concentration gradients are always associated with losses of work. If we could eliminate them, we could perform maximum work (but it would require infinite time).

A process without dissipative losses is called reversible. A process is reversible if the system may be returned to a prior state by reversing the motion. We can usually determine that a system is not reversible by recognizing when dissipative mechanisms exist.

Approaching Reversibility

We can approach reversibility by eliminating gradients within our system. To do this, we can perform motion by differential changes in forces, concentrations, temperatures, and so on. Let us consider a piston with a weight on top, at equilibrium. If we slide the weight off to the side, the change in potential energy of the weight is zero, and the piston rises, so its potential energy increases. If the piston hits a stop, kinetic energy is dissipated. Now let us subdivide the weight into two portions. If we move off one-half of the weight, the piston strikes the stop with less kinetic energy than before, and in addition, we have now raised half of the weight. If we repeat the subdivision again we would find that we could move increasing amounts of weight by decreasing the weight we initially move off the piston. In the limit, our weight would become like a pile of sand, and we would remove one grain at a time. Since the changes in the system are so small, only infinitesimal gradients would ever develop, and we would approach reversibility. The piston would never develop kinetic energy which would need to be dissipated.

Reversibility by a Series of Equilibrium States

When we move a system differentially, as just discussed, the system is at equilibrium along each step of the process. To test whether the system is at equilibrium at a particular stage, we can imagine freezing the process at that stage. Then we can ask whether the system would change if we left it at those conditions. If the system would remain static (i.e., not changing) at those conditions, then it must be at equilibrium. Because it is static, we could just as easily go one way as another ⇒ “reversible.” Thus, reversible processes are the result of infinitesimal driving forces.

Reversibility by Neglecting Viscosity and Friction

Real processes are not done infinitely slowly. In the previous examples we have used idealized pistons and cylinders for discussion. Real systems can be far from ideal and may have much more complex geometry. For example, projectiles can be fired using gases to drive them, and we need a method to estimate the velocities with which they are projected into free flight. One application of this is the steam catapult used to assist airplanes in becoming airborne from the short flight decks of aircraft carriers. Another application would be determination of the exit velocity of a bullet fired from a gun. These are definitely not equilibrium processes, so how can we begin to calculate the exit velocities? Another case would be the centrifugal pump. The pump works by rapidly rotating a propeller-type device. The pump simply would not work at low speed without velocity gradients! So what do we do in these cases? The answer is that we perform a calculation ignoring viscosity and friction. Then we apply an efficiency factor to calculate the real work done. The efficiency factors are determined empirically from our experience with real systems of a similar nature to the problem at hand. Efficiencies are introduced in Chapter 4. In the remainder of this chapter, we concentrate on the first part of the problem, calculation of reversible work.

![]() Viscosity and friction are frequently ignored for an estimation of optimum work, and an empirical efficiency factor is applied based on experience with similar systems.

Viscosity and friction are frequently ignored for an estimation of optimum work, and an empirical efficiency factor is applied based on experience with similar systems.

Example 2.1. Isothermal reversible compression of an ideal gas

Calculate the work necessary to isothermally perform steady compression of two moles of an ideal gas from 1 to 10 bar and 311 K in a piston. An isothermal process is one at constant temperature. The steady compression of the gas should be performed such that the pressure of the system is always practically equal to the external pressure on the system. We refer to this type of compression as “reversible” compression.

Solution

System: closed; Basis: one mole

WEC = –8.314 J/mol-K · 311 K ln(1/10) = 5954 J/mol

WEC = 2(5954) = 11,908 J

Note: Work is done on the gas since the sign is positive. This is the sign convention set forth in Eqn. 2.3. If the integral for Eqn. 2.3 is always written as shown with the initial state as the lower limit of integration and the P and V properties of the system, the work on the gas will always result with the correct sign.

2.5. Heat Flow

A very simple experiment shows us that heat transport is also related to energy. If two steel blocks of different temperature are placed in contact with one another, but otherwise are insulated from their surroundings, they will come to equilibrium at a common intermediate temperature. The warmer block will be cooled, and the colder block will be warmed.

Qblock 1 = –Qblock 2

Heat is transferred at a boundary between the blocks. Therefore, heat is not a property of the system. It is a form of interaction at the boundary which transfers internal energy. If heat is added to a system for a finite period of time, then the energy of the system increases because the kinetic energy of the molecules is increased. When an object feels hot to our touch, it is because the kinetic energy of molecules is readily transferred to our hand.

Since the rate of heating may vary with time, we must recognize that the total heat flows must be summed (or integrated) over time. In general, we can represent a differential contribution by

We can also relate the internal energy change and heat transfer for either block in a differential form:

An idealized system boundary that has no resistance to heat transfer but is impervious to mass is called a diathermal wall.

2.6. Path Properties and State Properties

In the previous example, we have used an isothermal path. It is convenient to define other terms which describe pathways concisely. An isobaric path is one at constant pressure. An isochoric path is one at constant volume. An adiabatic path is one without heat transfer.

The heat and work transfer necessary for a change in state are dependent on the pathway taken between the initial and final states. A state property is one that is independent of the pathway taken. For example, when the pressure and temperature of a gas are changed and the gas is returned to its initial state, the net change in temperature, pressure, and internal energy is zero, and these properties are therefore state properties. However, the net work and net heat transfer will not necessarily be zero; their values will depend on the path taken. Also, it is helpful to recall that heat and work are not properties of the system; therefore, they are not state properties.

![]() The work and heat transfer necessary for a change in state are dependent on the pathway taken between the initial and final state.

The work and heat transfer necessary for a change in state are dependent on the pathway taken between the initial and final state.

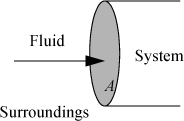

Example 2.2. Work as a path function

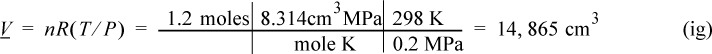

Consider 1.2 moles of an ideal gas in a piston at 298 K and 0.2 MPa and at volume V1. The gas is expanded isothermally to twice its original volume, then cooled isobarically to V1. It is then heated at constant volume back to T1. Demonstrate that the net work is non-zero, and that the work depends on the path.

First sketch the process on a diagram to visualize the process as shown in Fig. 2.2. Determine the initial volume:

Figure 2.2. Schematic for Example 2.2.

1. Isothermally expand that gas:

2. Isobarically cool down to V1:

3. Heat at constant volume back to T1:

⇒WEC = 0 (because dV = 0 over entire step)

We have returned the system to its original state and all state properties have returned to their initial values. What is the total work done on the system?

Therefore, we conclude that work is a path function, not a state function.

Exercise: If we reverse the path, the work will be different; in fact, it will be positive instead of negative (+573.6 J). If we change the path to isobarically expand the gas to double the volume (W = –2973 J), cool to T1 at constant volume (W = 0 J), then isothermally compress to the original volume (W = –2060 J), the work will be –913 J.

Note: Heat was added and removed during the process of Example 2.2 which has not been accounted for above. The above process transforms work into heat, and all we have done is computed the amount of work. The amount of heat is obviously equal in magnitude and opposite in sign, in accordance with the first law. The important thing to remember is that work is a path function, not a state function.

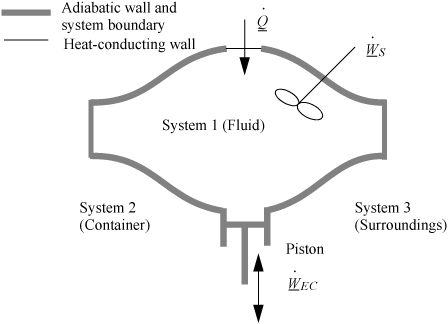

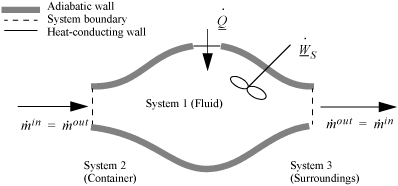

2.7. The Closed-System Energy Balance

A closed system is one in which no mass flows in or out of the system, as shown in Fig. 2.3. The introductory sections have discussed heat and work interactions, but we have not yet coupled these to the energy of the system. In the transformations we have discussed, energy can cross a boundary in the form of expansion/contraction work (–∫ PdV), shaft work (WS), and heat (Q)4. There are only two ways a closed system can interact with the surroundings, via heat and work interactions. If we put both of these possibilities into one balance equation, then developing the balance for a given application is simply a matter of analyzing a given situation and deleting the balance terms that do not apply. The equation terms can be thought of as a check list.

Figure 2.3. Schematic of a closed system.

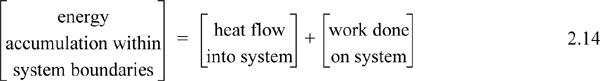

Experimentally, scientists discovered that if heat and work are measured for a cyclical process which returns to the initial state, the heat and work interactions together always sum to zero. This is an important result! This means that, in non-cyclical processes where the sum of heat and work is non-zero, the system has stored or released energy, depending on whether the sum is positive or negative. In fact, by performing enough experiments, scientists decided that the sum of heat and work interactions in a closed system is the change in energy of the system! To develop the closed-system energy balance, let us first express the balance in terms of words.

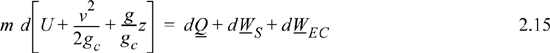

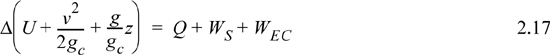

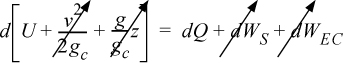

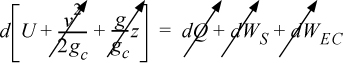

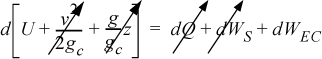

Energy within the system is composed of the internal energy (e.g., U), and the kinetic (mu2/2gc) and potential energy (mgz/gc) of the center of mass. For closed systems, the “check list” equation is:

The left-hand side summarizes changes occurring within the system boundaries and the right-hand side summarizes changes due to interactions at the boundaries. It is a recommended practice to always write the balance in this convention when starting a problem. We will follow this convention throughout example problems in Chapters 2–4 and relax the practice subsequently. The kinetic and potential energy of interest in Eqn. 2.15 is for the center of mass, not the random kinetic and potential energy of molecules about the center of mass. The balance could also be expressed in terms of molar quantities, but if we do so, we need to introduce molecular weight in the potential and kinetic energy terms. Since the mass is constant in a closed system, we may divide the above equation by m,

![]() Closed-system balance. The left-hand side summarizes changes inside the boundaries, and the right-hand side summarizes interactions at the boundaries.

Closed-system balance. The left-hand side summarizes changes inside the boundaries, and the right-hand side summarizes interactions at the boundaries.

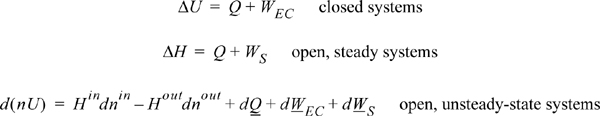

where heat and work interactions are summed for multiple interactions at the boundaries. We can integrate Eqn. 2.16 to obtain

We may also express the energy balance in terms of rates of change,

where ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() Frequently, the kinetic and potential energy changes are small (as we will show in Example 2.9), in a closed system shaft work is not common, and the balance simplifies to

Frequently, the kinetic and potential energy changes are small (as we will show in Example 2.9), in a closed system shaft work is not common, and the balance simplifies to

Example 2.3. Internal energy and heat

In Section 2.5 on page 46 we discussed that heat flow is related to the energy of system, and now we have a relation to quantify changes in energy. If 2000 J of heat are passed from the hot block to the cold block, how much has the internal energy of each block changed?

Solution

First choose a system boundary. Let us initially place system boundaries around each of the blocks. Let the warm block be block1 and the cold block be block2. Next, eliminate terms which are zero or are not important. The problem statement says nothing about changes in position or velocity of the blocks, so these terms can be eliminated from the balance. There is no shaft involved, so shaft work can be eliminated. The problem statement doesn’t specify the pressure, so it is common to assume that the process is at a constant atmospheric pressure of 0.101 MPa. The cold block does expand slightly when it is warmed, and the warm block will contract; however, since we are dealing with solids, the work interaction is so small that it can be neglected. For example, the blocks together would have to change 10 cm3 at 0.101 MPa to equal 1 J out of the 2000 J that are transferred.

Therefore, the energy balance for each block becomes:

We can integrate the energy balance for each block:

The magnitude of the heat transfer between the blocks is the same since no heat is transferred to the surroundings, but how about the signs? Let’s explore that further. Now, placing the system boundary around both blocks, the energy balance becomes:

Note that the composite system is an isolated system since all heat and work interactions across the boundary are negligible. Therefore, ΔU = 0 or by dividing in subsystems, ΔUblock1 + ΔUblock2 = 0 which becomes ΔUblock1 = –ΔUblock2. Notice that the signs are important in keeping track of which system is giving up heat and which system is gaining heat. In this example, it would be easy to keep track, but other problems will be more complicated, and it is best to develop a good bookkeeping practice of watching the signs. In this example the heat transfer for the initially hot system will be negative, and the heat transfer for the other system will be positive. Therefore, the internal energy changes are ΔUblock1 = –2000 J and ΔUblock2 = 2000 J.

Although very simple, this example has illustrated several important points.

1. Before simplifying the energy balance, the boundary should be clearly described by a statement and/or a sketch.

2. A system can be subdivided into subsystems. The composite system above is isolated, but the subsystems are not. Many times, problems are more easily solved, or insight is gained by looking at the overall system. If the subsystem balances look difficult to solve, try an overall balance.

3. Positive and negative energy signs are important to use carefully.

4. Simplifications can be made when some terms are small relative to other terms. Calculation of the expansion contraction work for the solids is certainly possible above, but it has a negligible contribution. However, if the two subsystems had included gases, then this simplification would have not been reasonable.

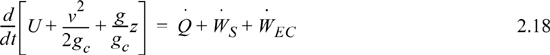

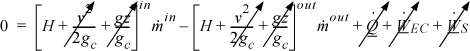

2.8. The Open-System, Steady-State Balance

Having established the energy balance for a closed system, and, from Section 2.3, the work associated with flowing fluids, let us extend these concepts to develop the energy balance for a steady-state flow system. The term steady-state means the following:

1. All state properties throughout the system are invariant with respect to time. The properties may vary with respect to position within the system.

2. The system has constant mass, that is, the total inlet mass flow rate equals the total outlet mass flow rates, and all flow rates are invariant with respect to time.

3. The center of mass for the system is fixed in space. (This restriction is not strictly required, but will be used throughout this text.)

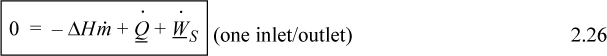

To begin, we write the balance in words, by adding flow to our previous closed-system balance. There are only three ways the surroundings can interact with the system: flow, heat, and work. A schematic of an open steady-state system is shown in Fig. 2.4. In consideration of the types of work encountered in steady-state flow, recognize that expansion/contraction work is rarely involved, so this term is omitted at this preliminary stage. This is because we typically apply the steady-state balance to systems of rigid mechanical equipment, and there is no change in the size of the system. Therefore, the expansion/contraction work term is set to 0.

Figure 2.4. Schematic of a steady-state flow system.

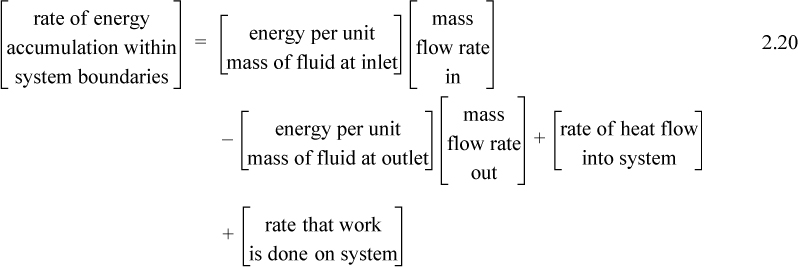

The balance in words becomes time-dependent since we work with flow rates:

Again, we follow the convention that the left-hand side quantifies changes inside our system. Consider the change of energy inside the system boundary given by the left-hand side of the equation. Due to the restrictions placed on the system by steady-state, there is no accumulation of energy within the system boundaries, so the left-hand side of Eqn. 2.20 becomes 0.

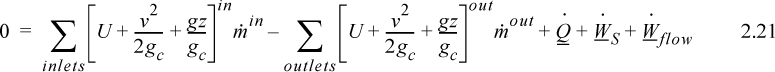

As a result,

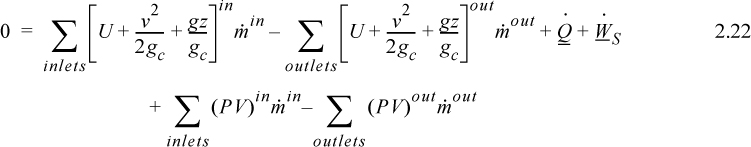

where heat and work interactions are summed over all boundaries. The flow work from Eqn. 2.7 may be inserted and summed over all inlets and outlets,

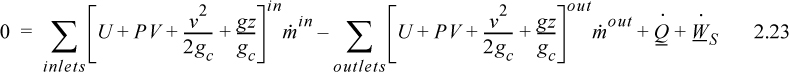

and combining flow terms:

Enthalpy

Note that the quantity (U + PV) arises quite naturally in the analysis of flow systems. Flow systems are very common, so it makes sense to define a single symbol that denotes this quantity:

H ≡ U + PV

Thus, we can tabulate precalculated values of H and save steps in calculations for flow systems. We call H the enthalpy.

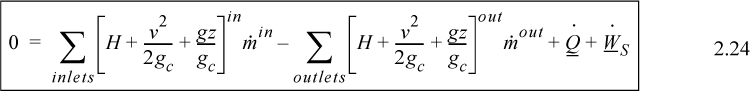

The open-system, steady-state balance is then,

where the heat and work interactions are summations of the individual heat and work interactions over all boundaries.

Note: Q is positive when the system gains heat energy; W is positive when the system gains work energy; ![]() and

and ![]() are always positive; and

are always positive; and ![]() is positive when the systems gains mass and zero for steady-state flow. Mass may be replaced with moles in a non-reactive system with appropriate care for unit conversion.

is positive when the systems gains mass and zero for steady-state flow. Mass may be replaced with moles in a non-reactive system with appropriate care for unit conversion.

Note that the relevant potential and kinetic energies are for the fluid entering and leaving the boundaries, not for the fluid which is inside the system boundaries. When only one inlet and one outlet stream are involved, the steady-state flow rates must be equal, and

When kinetic and potential energy changes are negligible, we may write

where ΔH = Hout – Hin. We could use molar flow rates for Eqns. 2.24 through 2.26 with the usual care for unit conversions of kinetic and potential energy. For an open steady-state system meeting the restrictions of Eqn. 2.26, we may divide through by the mass flow rate to find

In common usage, it is traditional to relax the convention of keeping only system properties on the left side of the equation. More simply we often write:

Compare Eqns. 2.19 and 2.28. Energy and enthalpy do not come from different energy balances, where the “closed system” balance uses U and WEC and the “open system” balance uses H and Ws. Rather, the terms result from logically simplifying the generalized energy balance shown in the next section.

Comment on Δ Notation

In a closed system we use the Δ symbol to denote the change of a property from initial state to final state. In an open, steady-state system, the left-hand side of the energy balance is zero. Therefore, we frequently write Δ as a shorthand notation to combine the first two flow terms on the right-hand side of the balance, with the symbol meaning “outlet relative to inlet” as shown above. You need to learn to recognize which terms of the energy balance are zero or insignificant for a particular problem, whether a solution is for a closed or open system, and whether the Δ symbol denotes “outlet relative to inlet” or “final relative to initial.”

Understanding Enthalpy and Shaft Work

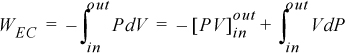

Consider steady-state, adiabatic, horizontal operation of a pump, turbine, or compressor. It is possible to conceive of a closed packet of fluid as the system while it flows through the equipment. After analyzing the system from this perspective, we can switch to the open-system perspective to gain insight about the relation between open systems and closed systems, energy and enthalpy, and EC work and shaft work. As a bonus, we obtain a handy relation for estimating pump work and the enthalpy of compressed liquids.

In the conception of a closed-system fluid packet, no mass moves across the system boundary. The system, as we have chosen it, does not include a shaft even though it will move past the shaft. If you have trouble seeing this, remember that the system boundaries are defined by the conceived packet of mass. Since the system boundary does not contain the shaft before the packet enters, or after the packet exits, it cannot contain the shaft as it moves through the turbine. The system simply deforms to envelope the shaft. Therefore, all work for this closed system is technically expansion/contraction work; the closed-system expansion/contraction work is composed of the flow work and shaft work that we have seen from the open-system perspective. It is difficult to describe exactly what happens to the system at every point, but we can say something about how it begins and how it ends. This observation leads to what is called an integral method of analysis.

System: closed, adiabatic; Basis: packet of mass m. The kinetic and potential energy changes are negligible:

Integrating from the inlet (initial) state to the outlet (final) state:

Uout – Uin = WEC

We may change the form of the integral representing work via integration by parts:

We recognize the term PV as representing the work done by the flowing fluid entering and leaving the system; it does not contribute to the work of the device. Therefore, the work interaction with the turbine is the remaining integral, ![]() . Substitution gives,

. Substitution gives,

Switching to the open-system perspective, Eqn. 2.28 gives

Recalling that H = U + PV and comparing the last two equations means Ws = ∫VdP is the work done using the pump, compressor, or turbine as the system. Furthermore, the appearance of the PV contribution in combination with U occurs naturally as part of the integration by parts. Physically, work is always “force times distance.” Though this derivation has been restricted to an adiabatic device, the result is general to devices including heat transfer as we show later in Section 5.7.

Note: The shaft work given by dWS = VdP is distinct from expansion/contraction work, dWEC = PdV. Moreover, both are distinct from flow work, dWflow = PVdm.

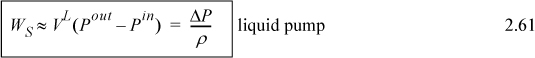

Several practical issues may be considered in light of Eqn. 2.31. First, the work done on the system is negative when the pressure change is negative, as in proceeding through a turbine or expander. This is consistent with our sign convention. Second, when considering gas flow, the integration may seem daunting if an ideal gas is not involved because of the complicated manner that V changes with T and P. Rather, for gases, we can frequently work with the enthalpy for a given state change. The enthalpy values for a state change read from a table or chart lead to Ws directly using Eqn. 2.30. For liquids, however, the integral can be evaluated quickly. Volume can often be approximated as constant, especially when Tr < 0.75. In that case, we obtain by integration an equation for estimating pump work:

![]() Shaft work for a liquid pump or turbine where kinetic and potential energy changes are small and Tr < 0.75 so that the fluid is incompressible.

Shaft work for a liquid pump or turbine where kinetic and potential energy changes are small and Tr < 0.75 so that the fluid is incompressible.

Example 2.4. Pump work for compressing H2O

Use Eqn. 2.31 to estimate the work of compressing 20°C H2O from a saturated liquid to 5 and 50 MPa. Compare to the values obtained using the compressed liquid steam tables.

Solution

For H2O, Tr = 0.75 corresponds to 212°C, so we are safe on that count. We can calculate the pump work from Eqn. 2.31, reading Psat = 0.00234 MPa and VL = 1.002 cm3/g from the saturation tables at 20°C:

⇒ ΔH ≈ VLΔP = 1.002 cm3/g(50 MPa – 0.00234 MPa) = 50.1 MPa-cm3/g for 50 MPa

⇒ ΔH ≈ VLΔP = 1.002 cm3/g(100 MPa – 0.00234 MPa) = 100.2 MPa-cm3/g for 100 MPa

A convenient way of converting units for these calculations is to multiply and divide by the gas constant, noting its different units. This shortcut is especially convenient in this case, e.g.,

ΔH = 50.1 MPa-cm3/g ·(8.314 J/mole-K)/(8.314 MPa-cm3/mole-K) = 50.1 kJ/kg

ΔH = 100.2 MPa-cm3/g ·(8.314 J/mole-K)/(8.314 MPa-cm3/mole-K) = 100.2 kJ/kg

Note that, for water, the change in enthalpy in kJ/kg is roughly equal to the pressure rise in MPa because the specific volume is so close to one and Psat << P. That is really handy.

The saturation enthalpy is read from the saturation tables as 83.95 kJ/kg. The values given in the compressed liquid table (at the end of the steam tables) are 88.6 kJ/kg at 5 MPa and 130 kJ/kg at 50 MPa, corresponding to estimated work values of 4.65 and 46.1 kJ/kg. The estimation error in the computed work is about 7 to 9%, and smaller for lower pressures. This degree of precision is generally satisfactory because the pump work itself is usually small relative to other work and terms (like the work produced by a turbine in a power cycle).

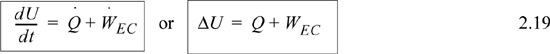

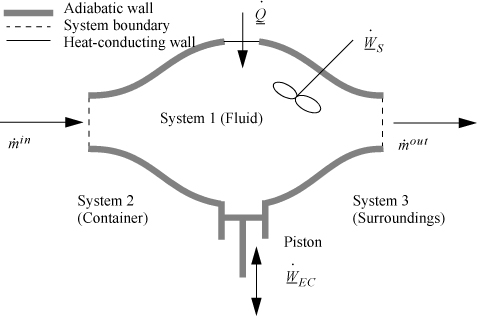

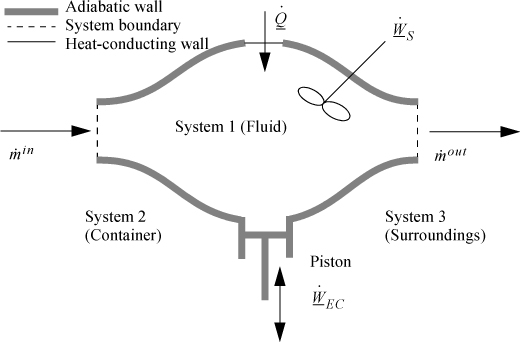

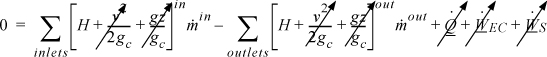

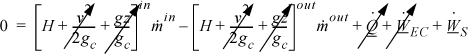

2.9. The Complete Energy Balance

An open-system that does not meet the requirements of a steady-state system is called an unsteady-state open-system as shown in Fig. 2.5. The mass-in may not equal the mass-out, or the system state variables (e.g., temperature) may change with time, so the system itself may gain in internal energy, kinetic energy, or potential energy. An example of this is the filling of a tank being heated with a steam jacket. Another example is the inflation of a balloon, where there is mass flow in and the system boundary expands. These considerations lead to a general equation which is applicable to open or closed systems,

Figure 2.5. Schematic of a general system.

where the heat and work interactions are summations of the individual heat and work interactions over all boundaries. We also may write this with the time dependence implied:

Note: The signs and conventions are the same as presented following Eqn. 2.24.

Usually, the closed-system or the steady-state equations are sufficient by themselves. But for unsteady-state open systems, the entire equation must be considered. Fortunately, even when the entire energy balance is applied, some of the terms are usually not necessary for a given problem, so fewer terms are usually needed than shown in Eqn. 2.33. An objective of this text is to build your ability to recognize which terms apply to a given problem.

2.10. Internal Energy, Enthalpy, and Heat Capacities

Before we proceed with more examples, we need to add another thermodynamic tool. Unfortunately, there are no “internal energy” or “enthalpy” meters. In fact, these state properties must be “measured” indirectly by other state properties. The Gibbs phase rule tells us that if two state variables are fixed in a pure single-phase system, then all other state variables will be fixed. Therefore, it makes sense to measure these properties in terms of P, V, and T. In addition, if this relation is developed, it will enable us to find P, V, and/or T changes for a given change in ΔU or ΔH. In Example 2.3, where a warm and cold steel blocks were contacted, we solved the problem without calculating the change in temperature for each block. However, if we had a relation between U and T, we could have calculated the temperature changes. The relations that we seek are the definitions of the heat capacities.

Constant Volume Heat Capacity

The constant of proportionality between the internal energy change at constant volume and the temperature change is known as the constant volume heat capacity. The constant volume heat capacity is defined by:

Since temperature changes are easily measured, internal energy changes can be calculated once CV is known. CV is not commonly tabulated, but, as shown below, it can be easily determined from the constant pressure heat capacity, which is commonly available.

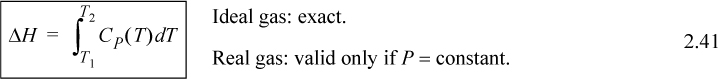

Constant Pressure Heat Capacity

In the last two sections, we have introduced enthalpy, and we can relate the change in enthalpy of a system to temperature in a manner analogous to the method used for internal energy. This relationship will involve a new heat capacity, the heat capacity at constant pressure defined by:

where H is the enthalpy of the system.

The use of two heat capacities, CV and CP, forces us to think of constant volume or constant pressure as the important distinction between these two quantities. The important quantities are really internal energy versus enthalpy. You simply must convince yourself to remember that CV refers to changes in U at constant volume, and CP refers to changes in H at constant pressure.

Relations between Heat Capacities, U and H

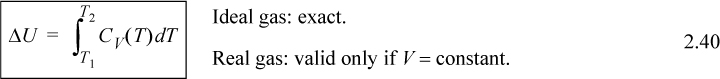

We have said that CV values are not readily available; therefore, how do we determine internal energy changes? Also, how do we determine enthalpy changes at constant volume or internal energy changes at constant pressure? We will return to the details of these questions in Chapters 6–8 and handle them rigorously, but the details have been rigorously followed by developers of thermodynamic charts and tables. Therefore, for relating the internal energy or enthalpy to temperature and pressure, a thermodynamic chart or table is preferred. If none is available, or properties are not tabulated in the state of interest, some exact relations and some approximate rules of thumb must be applied. The relations are also useful for introductory calculations while focus is on the energy balance rather than the property relations.

For an ideal gas,

Constant pressure heat capacities for ideal gases are tabulated in Appendix E. Constant volume heat capacities for ideal gases can readily be determined from Eqn. 2.38. For ideal gases, internal energy and enthalpy are independent of pressure as we implied with Eqn. 1.21. For real gases and for liquids, the relation between CP and CV is more complex, and derivatives of P-V-T properties must be used as shown rigorously in Examples 6.1, 6.6, and 6.9 and implemented thereafter. We will use thermodynamic tables and charts for real gases until these relations are developed.

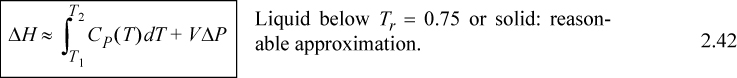

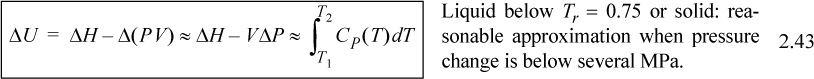

For liquids or solids, we typically calculate ΔH and correct the calculation if necessary as explained below. For liquids, it has been experimentally determined that internal energy is only very weakly dependent on pressure below Tr = 0.75. In addition, the molar volume is insensitive to pressure below Tr = 0.75. We demonstrated in Example 2.4 that,

![]() is the reduced temperature calculated by dividing the absolute temperature by the critical temperature. (A rigorous evaluation is considered in Example 6.1 on page 233.) The relations for solids and liquids are important because frequently the properties have not been measured, or the measurements available in charts and tables are not available at the pressures of interest. We may then summarize the relations of internal energy and enthalpy with temperature.

is the reduced temperature calculated by dividing the absolute temperature by the critical temperature. (A rigorous evaluation is considered in Example 6.1 on page 233.) The relations for solids and liquids are important because frequently the properties have not been measured, or the measurements available in charts and tables are not available at the pressures of interest. We may then summarize the relations of internal energy and enthalpy with temperature.

Note: These formulas do not account for phase changes which may occur.

Note that the heat capacity of a monatomic ideal gas can be obtained by differentiating the internal energy as given in Chapter 1, resulting in CV = 3/2 R and CP = 5/2 R. Heat capacities for diatomics are larger, CP = 7/2 R, and CV = 5/2 R near room temperature, and polyatomics are larger still. According to classical theory, each degree of freedom5 contributes 1/2R to CV. Kinetic and potential energy each contribute a degree of freedom in each dimension. A monatomic ideal gas has only three kinetic energy degrees of freedom, thus CV = 3/2 R. Diatomic molecules are linear so they have two additional degrees of freedom for the linear (one-dimensional) bond that has kinetic and potential energy both. In complicated molecules, the vibrations are characterized by modes. See the endflap to make a quick comparison. Monatomic solids have three degrees of freedom each for kinetic and vibrational energy, one for each principle direction, thus the law of Dulong and Petit, CVS = 3R is a first approximation. Low-temperature heat capacities of monatomic solids are explored more in Example 6.8. If you become curious about the manner in which the heat capacities of polyatomic species differ from those of the spherical molecules discussed in Chapter 1, you will find introductions to statistical thermodynamics explain the contributions of translation, rotation, and vibration. For polyatomic molecules, the heat capacity increases with molecular weight due to the increased number of degrees of freedom for each bond. In this text, ideal gas heat capacity values at 298 K are summarized inside the back cover of the book, and may be assumed to be independent of temperature over small temperature ranges near room temperature. The increase in heat capacity with temperature for diatomics and polyatomics is dominated by the vibrational contribution. The treatment of heat capacity by statistical thermodynamics is particularly interesting because it is a theory6 that often gives more accurate results than experimental calorimetric measurements. Commonly, engineers correlate ideal gas heat capacities with expressions like polynomials.

![]() Whenever we assume heat capacity to be temperature independent in this text, we mark the equation with a (*) symbol near the right margin.

Whenever we assume heat capacity to be temperature independent in this text, we mark the equation with a (*) symbol near the right margin.

We will frequently ignore the heat capacity dependence on T to make an approximate calculation. Whenever we assume heat capacity to be temperature independent in this text, we mark the equation with a (*) symbol near the right margin. Heat capacities represented as polynomials of temperature are available in Appendix E. The heat capacity depends on the state of aggregation. For example, water has a different heat capacity when solid (ice), liquid, or vapor (steam). The contribution of the heat capacity integral to the energy balance is frequently termed the sensible heat to communicate its contribution relative to latent heat (due to phase changes) or heat of reaction to be discussed later. Note that these are called “heats” even though they are enthalpy changes.

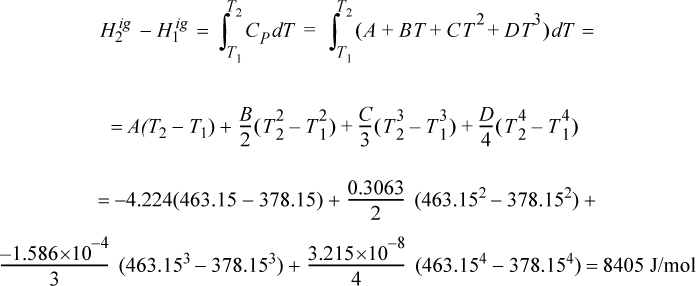

Example 2.5. Enthalpy change of an ideal gas: Integrating CPig(T)

Propane gas undergoes a change of state from an initial condition of 5 bar and 105°C to 25 bar and 190°C. Compute the change in enthalpy using the ideal gas law.

Solution

The ideal gas change is calculated via Eqn. 2.41 and is independent of pressure. The heat capacity constants are obtained from Appendix E.

Example 2.6. Enthalpy of compressed liquid

The compressed liquid tables are awkward to use for compressed liquid enthalpies because the pressure intervals are large. Using saturated liquid enthalpy values for water and hand calculations, estimate the enthalpy of liquid water at 20°C H2O and 5 and 50 MPa. Compare to the values obtained using the compressed liquid steam tables.

Solution

This is a common calculation needed for working with power plant condensate streams at high pressure. The relevant equation is Eqn. 2.42, but we can eliminate the temperature integral by selecting saturated water at the same temperature and then applying the pressure correction, i.e., applying Eqn. 2.39, ΔH ≈ VΔP relative to the saturation condition, giving H = Hsat + VΔP. The numerical calculations have already been done in Example 2.4 on page 55. Both calculations use the same approximation, even though the paths are slightly different. A more rigorous analysis is shown later in Example 6.1.

![]() This is a common calculation needed for working with power plant condensate streams at high pressure.

This is a common calculation needed for working with power plant condensate streams at high pressure.

Example 2.7. Adiabatic compression of an ideal gas in a piston/cylinder

Nitrogen is contained in a cylinder and is compressed adiabatically. The temperature rises from 25°C to 225°C. How much work is performed? Assume that the heat capacity is constant (CP/R = 7/2), and that nitrogen follows the ideal gas law.

Solution

System is the gas. Closed system, system size changes, adiabatic.

Note that because the temperature rise is specified, we do not need to know if the process was reversible.

Relation to Property Tables/Charts

In Section 1.4, we used steam tables to find internal energies of water as liquid or vapor. Tables or charts usually contain enthalpy and internal energy information, which means that these properties can be read from the source for these compounds, eliminating the need to apply Eqns. 2.40–2.43. This is usually more accurate because the pressure dependence of the properties that Eqns. 2.40–2.43 neglect has been included in the table/chart, although the pressure correction method applied in the previous example for liquids is generally accurate enough for liquids. Energy and enthalpy changes spanning phase transitions can be determined directly from the tables since energies and enthalpies of phase transitions are implicitly included in tabulated values.

Estimation of Heat Capacities

If heat capacity information cannot be located from appendices in this text, from the NIST Chemistry WebBook7, or from reference handbooks, it can be estimated by several techniques offered in the Chemical Engineer’s Handbook8 and The Properties of Gases and Liquids.9

Phase Transitions (Liquid-Vapor)

Enthalpies of vaporization are tabulated in Appendix E for selected substances at their normal boiling temperatures (their saturation temperatures at 1.01325 bar). In the case of the steam tables, Section 1.4 shows that the energies and enthalpies of vaporization of water are available along the entire saturation curve. Complete property tables for some other compounds are available in the literature or online, however, most textbooks present charts to conserve space, and we follow that trend. In the cases where tables or charts are available, their use is preferred for phase transitions away from the normal boiling point, although a hypothetical path that passes through the normal boiling point can usually be constructed easily.

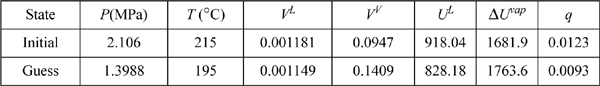

The energy of vaporization is more difficult to find than the enthalpy of vaporization. It can be calculated from the enthalpy of vaporization and the P-V-T properties. Since U = H – PV,

ΔUvap = ΔHvap – Δ(PV)vap = ΔHvap – (PsatV)V – (PsatV)L = ΔHvap – Psat(VV – VL)

Far from the critical point, the molar volume of the vapor is much larger than the molar volume of the liquid. Further, at the normal boiling point (the saturation temperature at 1.01325 bar), the ideal gas law is often a good approximation for the vapor volume,

Estimation of Enthalpies of Vaporization

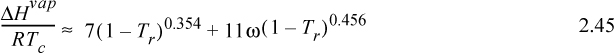

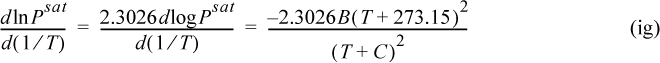

If the enthalpy of vaporization cannot be located in the appendices or a standard reference book, it may be estimated by several techniques offered and reviewed in the Chemical Engineer’s Handbook and The Properties of Gases and Liquids. One particularly convenient correlation is10

where Tr is reduced temperature, ω is the acentric factor (to be described in Chapter 7), also available on the back flap. If accurate vapor pressures are available, the enthalpy of vaporization can be estimated far from the critical point (i.e., Tr < 0.75) by the Clausius–Clapeyron equation:

The background for this equation is developed in Section 9.2. Vapor pressure is often represented by the Antoine equation, logPsat = A – B/(T + C). If Antoine parameters are available, they may be used to estimate the derivative term of Eqn. 2.46,

where T is in °C, and B and C are Antoine parameters for the common logarithm of pressure. For Antoine parameters intended for other temperature or pressure units, the equation must be carefully converted. The temperature limits for the Antoine parameters must be carefully followed because the Antoine equation does not extrapolate well outside the temperature range where the constants have been fit. If Antoine parameters are unavailable, they can be estimated to roughly 10% accuracy by the shortcut vapor pressure (SCVP) model, discussed in Section 9.3,

where the units of Pc match the units of Psat, Tc is in K, and T is in °C.

Phase Transitions (Solid-Liquid)

Enthalpies of fusion (melting) are tabulated for many substances at the normal melting temperatures in the appendices as well as handbooks. Internal energies of fusion are not usually available, however the volume change on melting is usually very small, resulting in internal energy changes that are nearly equal to the enthalpy changes:

Unlike the liquid-vapor transitions, where Tsat depends on pressure, the melting (solid-liquid) transition temperature is almost independent of pressure, as illustrated schematically in Fig. 1.7.

2.11. Reference States

Notice that our heat capacities do not permit us to calculate absolute values of internal energy or enthalpy; they simply permit us to calculate changes in these properties. Therefore, when is internal energy or enthalpy equal to zero—at a temperature of absolute zero? Is absolute zero a reasonable place to assign a reference state from which to calculate internal energies and enthalpies? Actually, we don’t usually solve this problem in engineering thermodynamics for the following two reasons:11 1) for a gas, there would almost always be at least two phase transitions between room temperature and absolute zero that would require knowledge of energy changes of phase transitions and heat capacities of each phase; and 2) even if phase transitions did not occur, the empirical fit of the heat capacity represented by the constants in the appendices are not valid down to absolute zero! Therefore, for engineering calculations, we arbitrarily set enthalpy or internal energy equal to zero at some convenient reference state where the heat capacity formula is valid. We calculate changes relative to this state. The actual enthalpy or internal energy is certainly not zero, it just makes our reference state location clear. If we choose to set the value of enthalpy to zero at the reference state, then HR = 0, and UR = HR – (PV)R where we use subscript R to denote the reference state. Note that UR and HR cannot be precisely zero simultaneously at the reference state. The reference state for water (in the steam tables) is chosen to set enthalpy of water equal to zero at the triple point. Note that PV is negligible at the reference state so that it appears that UR is also zero to the precision of the tabulated values, which is not rigorously correct. (Can you verify this in the steam tables? Which property is set to zero, and for which state of aggregation?). To clearly specify a reference state we must specify:

1. The composition which may or may not be pure.

2. The state of aggregation (S, L, or V).

3. The pressure.

4. The temperature.

As you will notice in the following problems, reference states are not necessary when working with a pure fluid in a closed system or in a steady-state flow system with a single stream. The numerical values of the changes in internal energy or enthalpy will be independent of the reference state.

![]() Reference states are not required for steady-state flow systems with only a few streams, but are recommended when many streams are present.

Reference states are not required for steady-state flow systems with only a few streams, but are recommended when many streams are present.

When multiple components are involved, or many inlet/outlet streams are involved, definition of reference states is recommended since flow rates of the inlet and outlet streams will not necessarily match one-to-one. The reference state for each component may be different, so the reference temperature, pressure, and state of aggregation must be clearly designated.

For unsteady-state open systems that accumulate or lose mass, reference states are imperative when values of ΔU or ΔH changes of the system or surroundings are calculated as the numerical values depend on the reference state. It is only when the changes for the system and surroundings are summed together that the reference state drops out for unsteady-state open systems.

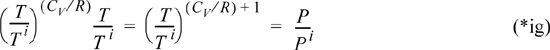

Ideal Gas Properties

For an ideal gas, we must specify only the reference T and P.12 An ideal gas cannot exist as a liquid or solid, and this fact completely specifies the state of our system. In addition, we need to set HR or UR (but not both!) equal to zero.

Also at all states, including the reference state, ![]() . The ideal gas approximation is reliable when contributions from intermolecular potential energy are relatively small. A convenient guideline is, in term of reduced temperature Tr = T/Tc, and reduced pressure Pr = P/Pc, where Pc is the critcal pressure.

. The ideal gas approximation is reliable when contributions from intermolecular potential energy are relatively small. A convenient guideline is, in term of reduced temperature Tr = T/Tc, and reduced pressure Pr = P/Pc, where Pc is the critcal pressure.

State Properties Including Phase Changes

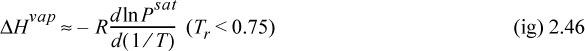

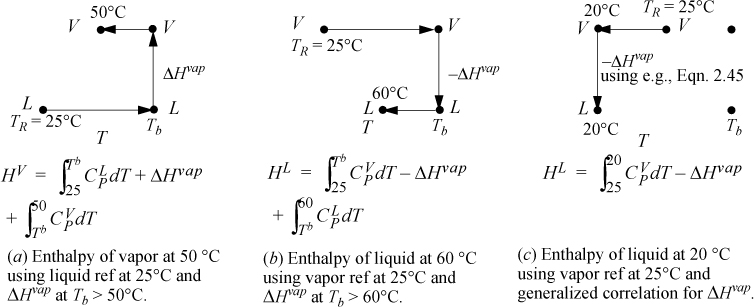

Problems will often involve phase changes. Throughout a problem, since the thermodynamic properties must always refer to the same reference state, phase changes must be incorporated into state properties relative to the state of aggregation of the reference state. To calculate a property for a fluid at T and P relative to a reference state in another phase, a sketch of the pathway from the reference state is helpful to be sure all steps are included. Several pathways are shown in Fig. 2.6 for different reference states. Note that the ideal gas reference state with the generalized correlation for the heat of vaporization (option (c)) is convenient because it does not require liquid heat capacities. The accuracy of the method depends on the accuracy of the generalized correlation or the technique used to estimate the heat of vaporization. Option (c) is frequently used in process simulators. In some cases the user may have flexibility in specifying the correlation used to estimate the heat of vaporization.

Figure 2.6. Illustrations of state pathways to calculate properties involving liquid/vapor phase changes. The examples are representative, and modified paths would apply for states above the normal boiling point, Tb. Similar pathways apply for solid/liquid or solid/vapor transformations. Note that a generalized correlation is used for ΔHvap which differs from the normal boiling point value. The method is intended to be used at subcritical conditions. Pressure corrections are not illustrated for any paths here.

Example 2.8. Acetone enthalpy using various reference states

Calculate the enthalpy values for acetone as liquid at 20°C and vapor at 90°C and the difference in enthalpy using the following reference states: (a) liquid at 20°C; (b) ideal gas at 25°C and ΔHvap at the normal boiling point; (c) ideal gas at 25°C and the generalized correlation for ΔHvap at 20°C. Ignore pressure corrections and treat vapors as ideal gases.

Solution

Heat capacity constants are available in Appendix E. For all cases, 20°C is 293.15K, 90°C is 363.15K, and the normal boiling point is Tb = 329.15K.

a. HL = 0 because the liquid is at the reference state. The vapor enthalpy is calculated analogous to Fig. 2.6, pathway (a). The three terms of pathway (a) are HV = 4639 + 30200 + 2799 = 37,638 J/mol. The difference in enthalpy is ΔH = 37,638 J/mol.

b. HL will use a path analogous to Fig. 2.6, pathway (b). The three terms of pathway (b) are HL = 2366 – 30200 – 4638 = –32472 J/mol. HV is calculated using Eqn. 2.50, HV = 5166 J/mol. The difference is ΔH = 5166 + 32472 = 37,638 J/mol, same as part (a).

c. HL will use a path analogous to Fig. 2.6, pathway (c). The generalized correlation of Eqn. 2.45 predicts a heat of vaporization at Tb of 29,280 J/mol, about 3% low. At 20°C, the heat of vaporization is predicted to be 31,420 J/mol. The two steps in Fig. 2.6 (c) are HL = –365 – 31420 = –31785 J/mol. The enthalpy of vapor is the same calculated in part (b), HV = 5166 J/mol. The enthalpy difference is ΔH = 5166 + 31785 = 36,950 J/mol, about 2% low relative to part (b).

2.12. Kinetic and Potential Energy

The development of the energy balance includes potential and kinetic energy terms for the system and for streams crossing the boundary. When temperature changes occur, the magnitude of changes of U and H are typically so much larger than changes in kinetic and potential energy that the latter terms can be dropped. The next example demonstrates how this is justified.

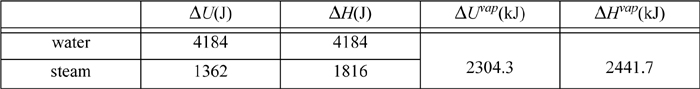

Example 2.9. Comparing changes in kinetic energy, potential energy, internal energy, and enthalpy

For a system of 1 kg water, what are the internal energy and enthalpy changes for raising the temperature 1°C as a liquid and as a vapor from 24°C to 25°C? What are the internal energy enthalpy changes for evaporating from the liquid to the vapor state? How much would the kinetic and potential energy need to change to match the magnitudes of these changes?

Solution

The properties of water and steam can be found from the saturated steam tables, interpolating between 20°C and 25°C. For saturated water or steam being heated from 24°C to 25°C, and for vaporization at 25°C:

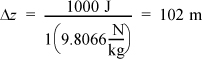

Of these values, the values for ΔU of steam are lowest and can serve as the benchmark. How much would kinetic and potential energy of a system have to change to be comparable to 1000 J?

Kinetic energy: If ΔKE = 1000 J, and if the kg is initially at rest, then the velocity change must be,

This corresponds to a velocity change of 161 kph (100 mph). A velocity change of this order of magnitude is unlikely in most applications except nozzles (discussed below). Therefore, kinetic energy changes can be neglected in most calculations when temperature changes occur.

Potential energy: If ΔPE = 1000 J, then the height change must be,

This is equivalent to about one football field in position change. Once again this is very unlikely in most process equipment, so it can usually be ignored relative to heat and work interactions. Further, when a phase change occurs, these changes are even less important relative to heat and work interactions.

![]() Velocity and height changes must be large to be significant in the energy balance when temperature changes also occur.

Velocity and height changes must be large to be significant in the energy balance when temperature changes also occur.

Example 2.9 demonstrates that kinetic and potential energy changes of a fluid are usually negligible when temperature changes by a degree or more. Moreover, kinetic and potential energy changes are closely related to one another in the design of piping networks because the temperature changes are negligible. The next example helps illustrate the point.

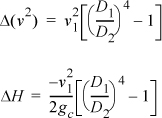

Example 2.10. Transformation of kinetic energy into enthalpy

Water is flowing in a straight horizontal pipe of 2.5 cm ID with a velocity of 6.0 m/s. The water flows steadily into a section where the diameter is suddenly increased. There is no device present for adding or removing energy as work. What is the change in enthalpy of the water if the downstream diameter is 5 cm? If it is 10 cm? What is the maximum enthalpy change for a sudden enlargement in the pipe? How will these changes affect the temperature of the water?

Solution

A boundary will be placed around the expansion section of the piping. The system is fixed volume, (![]() ), adiabatic without shaft work. The open steady-state system is under steady-state flow, so the left side of the energy balance is zero.

), adiabatic without shaft work. The open steady-state system is under steady-state flow, so the left side of the energy balance is zero.

Simplifying: ![]()

Liquid water is incompressible, so the volume (density) does not change from the inlet to the outlet. Letting A represent the cross-sectional area, and letting D represent the pipe diameter,![]() ,

,

D2/D1 = 2 ⇒ ΔH = –6.02 m2/s2 (1J/1kg-m2/s2) (½4–1)/2 = 17 J/kg

D2/D1 = 4 ⇒ ΔH = 18 J/kg

D2/D1 = ∞ ⇒ ΔH = 18 J/kg

To calculate the temperature rise, we can relate the enthalpy change to temperature since they are both state properties. From Eqn. 2.42, neglecting the effect of pressure,

Example 2.10 shows that the temperature rise due to velocity changes is very small. In a real system, the measured temperature rise will be slightly higher than our calculation presented here because irreversibilities are caused by the velocity gradients and swirling in the region of the sudden enlargement that we haven’t considered. These losses increase the temperature rise. In fluid mechanics, irreversible losses due to flow are characterized by a quantity known as the friction factor. The losses of a valve, fitting, contraction, or enlargement can be characterized empirically by the equivalent length of straight pipe that would result in the same losses. We will introduce these topics in Section 5.7. However, we conclude that from the standpoint of the energy balance, the temperature rise is still small and can be neglected except in the most detailed analysis such as the design of the piping network. In Example 2.10 the velocity decreases, and enthalpy increases due to greater flow work on the inlet than the outlet. Note that the above result for a liquid does not depend on whether the enlargement is rapid or gradual. A gradual taper will give the same temperature change since the energy balance relates the enthalpy change to the initial and final velocities, but not on the manner in which the change occurs.

Applications where kinetic and potential energy changes are important include solids such as projectiles, where the temperature changes of the solids are negligible and the purpose of the work is to cause accelerate or elevate the system. One example of this application is a steam catapult used to assist in take-off from aircraft carriers. A steam-filled piston + cylinder device is expanded, and the piston drags the plane to a velocity sufficient for the jet engines to lift the plane. While the kinetic and potential energy changes for the steam are negligible, the work done by the steam causes important kinetic energy changes in the piston and plane because of their large masses.

2.13. Energy Balances for Process Equipment

Several types of equipment are ubiquitous throughout industry, and facile abilities with the energy balance for these processes will permit more rapid analysis of composite systems where these units are combined. In this brief section we introduce valves and throttles used to regulate flow, nozzles, heat exchangers, adiabatic turbines and expanders, adiabatic compressors, and pumps.

Valves and Throttles

A throttling device is used to reduce the pressure of a flowing fluid without extracting any shaft work and with negligible fluid acceleration. Throttling is also known as Joule-Thomson expansion in honor of the scientists who originally studied the thermodynamics. An example of a throttle is the kitchen faucet. Industrial valves are modeled as throttles. Writing the balance for a boundary around the throttle valve, it is conventional to neglect any accumulation within the device since it is small relative to flow rates through the device, so the left-hand side is zero. At steady-state flow,

Changes in kinetic and potential energy are small relative to changes in enthalpy as we just discussed. When in doubt, the impact of changes in velocity can be evaluated as described in Example 2.9. The amount of heat transfer is negligible in a throttle. The boundaries are not expanding, and there is also no mechanical device for transfer of work, so the work terms vanish. Therefore, a throttle is isenthalpic:

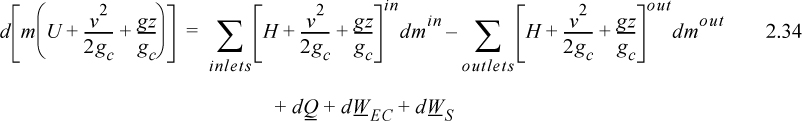

Nozzles

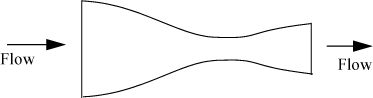

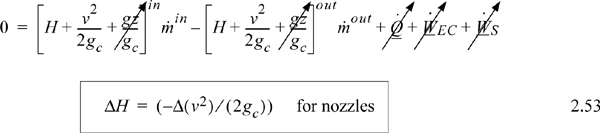

Nozzles are specially designed devices utilized to convert pressure drop into kinetic energy. Common engineering applications involve gas flows. An example of a nozzle is a booster rocket. Nozzles are also used on the inlets of impulse turbines to convert the enthalpy of the incoming stream to a high velocity before it encounters the turbine blades.13 Δu is significant for nozzles. A nozzle is designed with a specially tapered neck on the inlet and sometimes the outlet as shown schematically in Fig. 2.7. Nozzles are optimally designed at particular velocities/pressures of operation to minimize viscous dissipation.

Figure 2.7. Illustration of a converging-diverging nozzle showing the manner in which inlets and outlets are tapered.

The energy balance is written for a boundary around the nozzle. Any accumulation of energy in the nozzle is neglected since it is small relative to flow through the device and zero at steady state. Velocity changes are significant by virtue of the design of the nozzle. However, potential energy changes are negligible. Heat transfer and work terms are dropped as justified in the discussion of throttles. Reducing the energy balance for a nozzle shows the following:

Properly designed nozzles cause an increase in the velocity of the vapor and a decrease in the enthalpy. A nozzle can be designed to operate nearly reversibly. Example 4.12 on page 162 describes a typical nozzle calculation.

Throttles are much more common in the problems we will address in this text. The meaning of “nozzle” in thermodynamics is much different from the common devices we term “nozzles” in everyday life. Most of the everyday devices we call nozzles are actually throttles.

Assessing when simplifications are justified requires testing the implications of eliminating assumptions. For example, to test whether a particular valve is acting more like a throttle or a nozzle, infer the velocities before and after the nozzle and compare to the enthalpy change. If the kinetic energy change is negligible relative to the enthalpy change then call it a throttle. Take note of the magnitude of the terms in the calculation so that you can understand how to anticipate a similar conclusion. For example, the volume change of a liquid due to a pressure drop is much smaller than that of a gas. With less expansion, the liquids accelerate less, making the throttle approximation more reasonable. This kind of systematic analysis and reasoning is more important than memorizing, say, that throttles are for liquids.

Heat Exchangers

Heat exchangers are available in a number of flow configurations. For example, in an industrial heat exchanger, a hot stream flows over pipes that carry a cold stream (or vice versa), and the objective of operation is to cool one of the streams and heat the other. A generic tube-in-shell heat exchanger can be illustrated by a line diagram as shown in Fig. 2.8. Tube-in-shell heat exchangers consist of a shell (or outer sleeve) through which several pipes pass. (The figure just has one pipe for simplicity.) One of the process streams passes through the shell, and the other passes through the tubes. Stream A in our example passes through the shell, and Stream B passes through the tubes. The streams are physically separated from one another by the tube walls and do not mix. Let’s suppose that Stream A is the hot stream and Stream B is the cold stream. In the figure, both streams flow from left to right. This type of flow pattern is called concurrent. The temperatures of the two streams will approach one another as they flow to the right. With this type of flow pattern, we must be careful that the hot stream temperature that we calculate is always higher than the cold stream temperature at every point in the heat exchanger.14 If we reverse the flow direction of Stream A, a countercurrent flow pattern results. With a countercurrent flow pattern, the outlet temperature of the cold stream can be higher than the outlet temperature of the hot stream (but still must be lower than the inlet temperature of the hot stream). The hot stream temperature must always be above the cold stream temperature at all points along the tubes in this flow pattern also.

Figure 2.8. Illustration of a generic heat exchanger with a concurrent flow pattern. The tube side usually consists of a set of parallel tubes which are illustrated as a single tube for convenience.