Chapter 10. Performing a content audit

Content is at the heart of a unified content strategy. Before you can model your content—and subsequently, unify it—you need to gain an intimate understanding of its nature and structure. During a content audit, you look at your organization’s content analytically and critically, which allows you to identify how effective the content is.

In addition, you analyze the content for opportunities for reuse. You look for similar and identical information, as well as for information that could be similar or identical, but is currently distinct. Once you see how your information is being used and reused, you can make decisions about how you might unify it.

This chapter describes what a content audit is and how to perform one; it also provides examples of content audit findings.

What is a content audit?

A content audit, as the name implies, is an accounting of the information in your organization. However, unlike the usual associations with the word audit—associations that strike fear into the hearts of many taxpayers—a content audit has positive results that enable your organization to save money if your findings are implemented. The purpose of a content audit is to analyze how content is written, organized, used, reused, and delivered to its various audiences.

Content audit vs. content inventory

Many people refer to a content inventory as a content audit, or sometimes a quantitative audit. For our purposes, when we talk about a content audit we mean the process of actually looking at the content and assessing its value and opportunities for reuse.

What’s involved in doing a content audit?

To get started on a content audit within your organization, you first need to identify your scope, and then select representative materials within that scope. The larger the scope, the more work involved, but the greater the return on investment.

Identifying scope

You don’t have to start big; doing a content audit within one area of an organization can realize significant returns and illustrate to other areas how, by including their content, the organization can realize even greater returns. It isn’t necessary to look at absolutely every piece of information—a representative sample is enough. You’ll start to see patterns that can then be extrapolated across your content set.

Selecting representative materials

After you’ve determined the scope of the audit, you need to select representative materials. Select as much content as you can, representing all the different departments included in your scope, not just the content that you create. Below are examples of content to look at depending on your focus.

Marketing: Look at samples including brochures, website, product packaging, point-of-sale materials, newsletters, press releases, ads, promos, and trade-show materials. Be sure to look at the same content on as many platforms as possible.

Publishing: Look at samples including trade press, textbooks, ancillary learning materials, eBooks, apps, journals, associated marketing materials, and any other content you produce. If you produce customer-branded content, be sure to include this as well.

Product content: Look at samples of help materials, manuals, and wikis. Be sure to select samples where content is or could be reused. If you outsource the manufacturing of your product to an original equipment manufacturer (OEM), include customer-branded content as well. Also look at technical support/customer support and knowledge bases. If you share content with learning materials or cover similar content be sure to include learning materials as well.

Learning materials: If your focus is learning materials, select samples of instructor-led, self-paced eLearning, virtual classroom, mobile learning, and apps.

You want to look at representative samples so you’re analyzing the full breadth of materials, and you need to look at like materials to assess content for reuse.

Assessing the quality of the content

Look at your content to determine:

• Is the content appropriate to the customer(s)?

• Does it use the customer’s terminology?

• How well is it written?

• Is the tone correct?

• Is the level of detail correct?

• Will it support the customer content scenarios?

• Are there any gaps?

• Does it help customers complete their tasks, make the right decisions, and satisfy their needs?

Assessing the opportunities for content reuse

Typically if authors want to reuse information they:

• Determine which information they want to reuse.

• Find the information in another document/section or even on another server in another area of the company.

• Copy and paste the information from one section of the document to another section, or from one document to another document.

• Rewrite or reformat the reused information to fit the new context.

Reusing content this way isn’t really reuse; it’s actually copy and paste. This results in multiple instances of the same piece of information occurring in the document or across documents. These instances are not linked or referenced to one another physically within the authoring or publishing tool. If the information needs to be updated, authors must first locate all instances of reuse, and then update each instance separately. This can be an extremely time-consuming process, and introduces much opportunity for error and inconsistency.

More often, content is written and rewritten and rewritten, often with changes or differences for each iteration. This results in inconsistent content and increased costs.

The content audit is intended to illustrate where opportunities to unify content throughout your organization exist; it provides the basis for your reuse strategy and modeling decisions.

Analyzing the content for reuse

After you’ve gathered together a representative sample of materials, you’re ready to start digging into it. This is the fun part and usually involves spreading large amounts of information all over your office, walking around with a highlighter and a stack of sticky notes, highlighting your findings, and taking notes as you go. It’s fun because it doesn’t involve doing anything beyond really examining your content closely to see what it contains and how it’s put together. Analyzing materials in this way is a discovery process about your content, something most organizations don’t have the opportunity to do in their day-to-day work. You’re not making any decisions at this point; instead, you’re seeing what you have and making observations about it.

Analyzing content occurs at two levels, at the top level of your representative samples, followed by a more detailed examination of the content.

Top-level analysis

A top-level analysis involves scanning various information products to find common information (for example, product descriptions, introductory information, procedures, disclaimers, and topics). If you have large documents that include tables of contents, you can compare the tables of contents to find similarities in chapter/section names. Such similarities often indicate similar/identical content within and across a documentation set. Start by spreading your information products out in front of you and highlighting areas that look like they might contain similar information. If all your content is electronic, scan your materials for sample sections you want to look at more closely and print them off. Yes, print! No, don’t print everything; we don’t want you killing whole forests. But you can’t easily mark up content that is electronic despite the functionality of some markup tools.

In-depth analysis

During the in-depth analysis, you examine the repeated information you identified during the top-level analysis. Repeated information can be as simple as copyright notices and warranty information, and as complex as whole sections of detail, particularly for product suites.

Once you’ve found instances of repeated information to scrutinize more closely, you can lay them out in a tabular format to see them all together at a glance. (See the examples that follow.) As you look at instances of repeated information, identify whether the content is identical or similar. If it is similar (or almost identical), which parts differ? Do the parts that differ need to differ? Are there valid reasons for differences such as product/information uniqueness? If the parts differ and there is no valid reason for the difference, identify this content as something that should be rewritten so it is identical for reuse in the future.

Content audit examples for reuse

The following examples show content audit findings for four fictional companies. Each example includes a top-level analysis showing potential content reuse, as well as a small in-depth analysis showing how the company could select a portion of the content for further analysis and interpret the findings.

Example 1 is for a Shakespearean theater company. They publish their content on the Web and in a print-based guide, but more and more of their customers are using mobile devices to access their site, and they don’t have a mobile site.

Example 2 is a publisher of scientific textbooks. They have beautiful textbooks supplemented by online learning materials, but they want to move to eBooks and they aren’t sure how to do that with their complex materials.

Example 3 is for a medical devices company that produces blood glucose monitoring meters. Because there are several versions of the meters, the company suspects there may be similarities—or inconsistencies—in the information produced for each version.

Example 4 shows reuse in learning materials. A business college that teaches investment courses receives feedback from students complaining that similar information in different courses (or even in the same course) is inconsistent. The college wants to build a database of reusable learning objects, or (RLOs), so that wherever information is repeated, it’s the same. In their audit, the college looks for places where the same information is used (for example, the same topics, but with a different depth or focus), so they can ensure it is consistent.

Example 1: Enterprise content

This example is for a Shakespearean theater company, The Bard. They attract attendees from all over North America. They publish their content in the newspaper and in a theater guide, as well as to the Web, Facebook, YouTube, Flickr, and Twitter. They do a lot of reuse between all the different channels, but it is all manual, time-consuming, and expensive. They are looking at government funding cuts in the next calendar year due to fiscal restraint measures and they have to find a better way of publishing content.

Top-level analysis

The Bard has a well-designed and easy-to-use website for learning about the plays, ordering tickets online, and finding out about all the other activities related to the theater, such as readings, music, and kids’ camps.

• Play selector page

• Play page

• Theater guide (print)

• Newspaper ad

• Facebook page

• Flickr

The main image for each play is used over and over again either in its entirety or as a partial image in small display areas.

Figures 10.1–10.3 illustrate the commonality of images and content. The Hamlet image was used in the play production selection page, the play description page, and in the playbill.

Figure 10.1. The Bard play production page.

Figure 10.2. Play detail page (Hamlet).

Figure 10.3. Program (Hamlet).

There’s also a lot of textual reuse in areas such as the descriptions of the plays and all the cast information.

When you look at their site on a smartphone, it’s easy to see why customers are frustrated, because the content is impossible to navigate (see Figure 10.4). In addition, all the features of the desktop site like ticket ordering are disabled on the smartphone.

Figure 10.4. Website on a smartphone.

Interpreting the findings

The Bard has a tremendous opportunity for reuse; however, the print-based materials are farmed out to an agency, so under the current process automated reuse beyond web deliverables is not possible.

In addition, there’s no mobile solution. A QR code is included in the print materials, which is a great idea, but it takes customers to the regular site. The regular site is very difficult to view on mobile without a lot of scrolling, and it’s impossible to purchase a ticket using a mobile device.

In-depth analysis

If we look closely at the content for a play on the website versus the same information in the program, it’s very similar. Web content for the description of the play is virtually identical to that in the theater guide, with the tiny exception of a tagline in the web content.

The newspaper ad uses the name of the play and dates, times, and so on, then only the tagline, not the more detailed description. The newspaper ad also uses quotes from play reviews that are also found on the website.

Interpreting the findings

The content could be identically reused.

Conclusion

There is a tremendous opportunity for reuse of images and text across all the channels. The Bard should consider generating the print materials from the same source content as the web materials to save money rather than going to an outside agency.

A specifically designed mobile site should be created to optimize the content for mobile and to enable ticket purchases.

Example 2: Publishing

Science Publishers, Inc. publishes trade press books, high school and college textbooks, and journals. They currently have four major areas in the organization handling the production of content:

• Web (marketing and business-to-consumer [B2C])

• Trade press and textbooks

• Ancillary learning materials

• Journals

Each of the production areas is isolated (siloed), and much of the work is manual with only the assistance of standard web publishing and desktop publishing tools. Content is shared by passing files back and forth through email and a shared file server. Science Publishers creates online learning materials to accompany the textbooks but wants to start delivering both content and additional learning materials on eReaders and tablets.

Top-level analysis

A top-level analysis of materials showed:

• Journals didn’t really have a lot of reuse other than some quotations incorporated into the textbooks.

• Some reuse between the marketing materials, “back of the book,” and B2C product descriptions.

• Significant reuse between the textbooks and additional learning materials:

• Images

• Objectives

• Concepts

• Terms and definitions

• Practice exercises

• Electronic flash cards

• Some reuse between textbooks (for example, a section on the digestive system was used in a basic biology text, in a text on nutrition, and in another on the human body).

Interpreting the findings

There was a great deal of opportunity for reuse.

In-depth analysis

An in-depth analysis showed that while the content was reusable, it was not exactly the same, and it was obviously copied and pasted. There were often tiny differences in images, some small text changes, and different punctuation.

The in-depth analysis on publishing to eReaders and tablets revealed some significant challenges and some exciting opportunities. Based on the functionality of E Ink eReaders (standard, grayscale, linear eReaders) there were a number of potential problems, including:

• Very dense content: a single paragraph could easily take up an entire eReader screen

• Two-column layout

• Complex tables

• Complex illustrations

• Illustrations that stretched across columns or pages

• Footnotes

• Sidebars

Interpreting the findings

Science Publishers would have to do a lot of work to transform their content from print-oriented textbooks to more simplistic layouts for E Ink eReaders and to ensure usability. Doable, but somewhat challenging.

Conclusion

Science Publishers has a tremendous opportunity for reuse between textbooks and additional educational materials. However, the task of transitioning to eReaders will be somewhat challenging. Tablets hold a better opportunity to represent the textbooks in a similar way to print, but more importantly they offer the opportunity to:

• Integrate the additional learning materials into the text so the student can learn by traditional reading and also by clicking out to videos, simulations, and interactive exercises.

• Redesign the textbook as an app with even greater interactivity and rich media.

Example 3: Product content

This example involves a medical devices company that produces blood glucose monitoring meters. Because there are several versions of the meters, the company suspects there may be similarities—or inconsistencies—in the information products created for each version. Their audit focuses on comparing content across information products so they can figure out how to reuse information and ensure consistency.

Interpreting the findings

The top-level analysis shows areas that warrant closer examination. For example, the company logo and contact information are used in every information product, and the product description is used in all but three. In addition, a number of topics related to the setup and use of the product are repeated throughout. This top-level analysis shows the findings for just one product—the blood glucose monitoring meter. Expanding the analysis to look at other products in the same family shows that up to 80 percent of the content could be reused. Looking even further at other related product lines shows additional commonality in conceptual information about the company and its products.

Top-level analysis

Table 10.1 represents the top-level analysis of their materials.

Table 10.1. Top-level analysis of information products

In-depth analysis

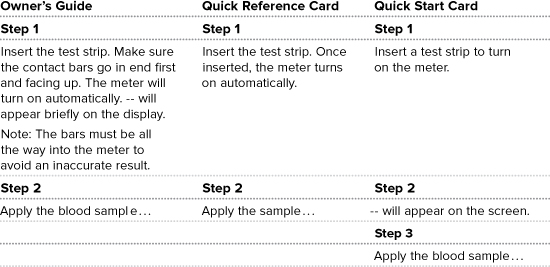

The results of the top-level analysis are used to drive the in-depth analysis. In this case, the in-depth analysis (see Table 10.2) shows similar information in the setup and use of the product.

Table 10.2. In-depth analysis of information products

Interpreting the findings

There are subtle differences in the first two samples (Owner’s Guide and Quick Reference Card), but the third sample (Quick Start Card) has a different second step. Are the differences necessary or will they confuse users? Quick Reference Cards provide concise information so the shorter steps are appropriate. The same holds true for the Quick Start Guide; however, the second step isn’t really a step. The differences in the steps should be reconsidered.

Conclusion

Although this example shows just a small portion of content, it illustrates the seemingly insignificant, yet critical, variations that can occur in content. In this case, the content would benefit from a unified strategy to ensure that it’s consistent each time the same information appears.

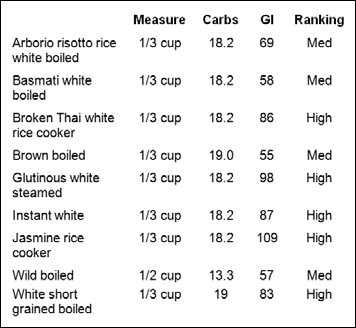

Example 4: Learning materials

A business college teaches classes in investment strategies, targeted to practitioners seeking further education or accreditation in financial planning, and to people who just want more information about their own investment planning. After receiving a number of student feedback forms complaining about inconsistencies in the course content, the college decided to conduct an audit of their materials in an attempt to unify common information. The college wants to build a database of RLOs so that wherever information is repeated, it’s the same. Their audit focuses on looking for places where the same information is used so they can ensure it’s consistent.

Top-level analysis

A top-level analysis of four courses (see Table 10.3) shows that a lot of content is repeated in a number of different places.

Table 10.3. Top-level analysis of learning materials

Interpreting the findings

The top-level analysis indicates that there is much repetition of certain subject areas throughout the different courses. Although the focus and the level of detail may be different from course to course, content should be examined more closely to determine if there are inconsistencies and to see if there are similarities that could potentially be unified.

In-depth analysis

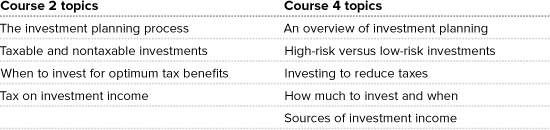

A more in-depth analysis of the topics related to investment strategies (see Table 10.4) shows similarities in the overviews of Course 2, which touches on investment strategies, and Course 4, whose entire focus is investing:

Table 10.4. In-depth analysis of learning materials

Note that many of the topics covered in Course 2 are similar to the topics in Course 4, similar enough that they should be compared to see if they are inconsistent, where they differ, where they should differ, and where they are alike.

Interpreting the findings

Closer examination of each topic shows that much of the content in “Investing to reduce taxes” and “Taxable and nontaxable investments” is similar. This is also the case for “How much to invest and when” and “When to invest for optimum tax benefits.” The information on investment planning, though, is inconsistent.

Conclusion

The findings in both the top-level and in-depth analyses show numerous opportunities for the college to reuse content and to correct inconsistencies. Correcting discrepancies is critical in learning materials; students learn information one way, then when they encounter an inconsistency in a future course (or sometimes even in the same course), they have to figure out which version is correct, increasing their cognitive load. If students cannot figure it out, they are left with conflicting information. This is especially critical in an eLearning environment where the materials themselves become the instructor; students often don’t have another source to help them figure out what’s wrong.

After discrepancies are corrected, information can be chunked into RLOs and reused in whichever course it is applicable. If more detail is required to teach the same topic in a more advanced course or to accommodate different learning objectives, information can be added to the RLO, with each level of detail comprising another RLO. Wherever the core RLO is used, however, it’s consistent.

Summary

Doing a thorough content audit is critical to implementing a reuse strategy because it tells you how content is written and how it’s currently being used, how it could be reused, and what needs to be done to create effective unified content.

1. Establish the scope of the audit.

2. Select representative samples of your content based on the scope of your project.

3. Look at the content itself to determine its appropriateness, quality of writing, and “fit” for the channel.

4. Assess the opportunities for content reuse.

5. Analyze the content for reuse.

A content audit can help you determine how to reuse content across a number of different information products. Where content is different, does it have to be different? Can information that is similar be made identical? Are there reasons for it being similar as opposed to identical (product name, for example)? Should content in one medium be identical to most of the content in another medium (for example, Web versus mobile)? How will your information products be used, and are there valid reasons to distinguish them from one another? These are the types of questions to answer as you develop an intimate understanding of your content.