Chapter 1. Essential Traits

There are a number of characteristics that all good design business owners share, and it’s important to remind ourselves of them from time to time.

Be curious

One of humanity’s greatest strengths is the desire to question. How does that work? Where did it come from? Why does it work that way? When was it invented? By questioning everything, we keep our minds active. Think of it as training—our minds are like muscles, and the more active they are, the stronger they become. The stronger they are, the greater the advantage you’ll have over other design business owners.

You and I were once the best in the world at asking questions—when we were kids. But we got older, we learned to mind our own business, and we lost a lot of interest in what happens around us.

You need to reawaken that interest, let it flourish, because the desire to question is vital when dealing with your clients. Good design fulfills a brief, and without asking the right questions (we’ll come to those in chapter 15), the brief won’t be suitable. The project will fail. You won’t delight.

One of my earliest projects in self-employment was to create an identity for a new English-themed bar and restaurant called Caramel. If I had asked more questions before starting the design work, I could’ve narrowed the focus to one or two brilliant ideas. But I wasn’t curious enough about my client’s specific design needs and about the audience she was targeting, and ultimately, neither of us was on board with the direction that needed to be taken. Because of my lack of curiosity, the client was left with too many unsuitable designs, and I was left without the second 50 percent of my fee.

Curiosity can also save you time and trouble in other ways. As a rule, I try to never fully accept anything as the truth until I’ve found out for myself if it is correct. I might have 99 percent confidence in my knowledge, but I always consider that remaining one percent, especially when talking to those with a difference of opinion.

A case in point: In 2009, a young designer named Jon Engle spread the news on his website that he was being sued for $18,000 by a stock agency for “stealing his own work.” His news quickly resulted in a #savejon hash-tag campaign on Twitter that spread like wildfire. Jon’s website crashed after his story hit the front page of Digg, and designers everywhere donated money to a legal aid fund that had been set up. But as the story emerged, the evidence suggested that he had indeed infringed upon the company’s copyright. Jon ultimately apologized to everyone via Twitter in the hope of making an honest restart, but not before thousands of designers around the world had rallied to his aid without first asking for both sides of the story. There are always two sides: Search them out.

Show empathy

When someone’s rude, unhelpful, or ignorant, there’s a reason. Before you judge, put yourself in the shoes of the other person. There are thousands of rational reasons why someone might be feeling off center.

The same applies when dealing with clients. Your projects won’t always run smoothly. Your clients won’t always treat you with the respect you deserve. This is part of business, and is something you need to accept.

An excellent example: After working for a month with a client from the United States, the emails he sent me became short, abrupt, and some might say, rude. It wasn’t until a few weeks later that I discovered his wife was very ill, and he was under a great deal of stress. That explained his attitude change in an instant. When this happens, remember there’s a good chance that whatever is amiss is not your fault, and don’t be afraid to ask your client if everything’s OK.

Have confidence

Being confident isn’t the same as being outgoing. It’s OK to be an introvert. Confidence means believing in yourself. If you don’t believe that what you have to offer is of any value, well, no one’s going to pay for it.

You need to build the confidence required to sell your skills. Without it, you won’t have a business. Until you’ve built a solid client base, you are your best salesperson. No one else is going to do it for you.

I once worked in telesales for The Scotsman, Scotland’s national newspaper, selling classified ads in travel supplements. I quickly learned that unless I saw the benefit in what I was selling, I’d never make a sale. During my training and on the mock phone calls, I wasn’t highlighting the benefit for the customer—namely, increased occupancy for her hotel. I needed to have confidence that people look to travel supplements when planning their holidays, and that I was calling hotel owners in an honest effort to help. Once I believed that and could convey that belief, my sales conversion rate rose to approximately 25 percent, and I ended the first day with the number of successful calls in double digits.

Don’t let ten, a hundred, or a thousand “no’s” put you off, because another thing I learned was that the more you practice selling, the better you become, and without those rejections, you’ll never find your most-valued customers.

Truth is, you get a lot of “no’s.” More often than not, the design inquiries I receive from potential clients don’t result in a working agreement. Why? Basically, we’re not always a good fit. The client tells me their budget won’t stretch, or they want to take a lead role in the actual design work, or the project deadline won’t accommodate the time I need, or one of dozens of other reasons. Sometimes I catch a red flag that puts me off doing business (more on red flags in chapter 14). But every time someone says “no,” I become more and more familiar with the objections raised and learn how to overcome them. If cost is prohibitive, the emphasis is shifted to how much my work can help boost client profits. If the time needed to complete the project is longer than expected, I reiterate how long solid design work lasts, and how it’s better to get it right the first time.

You’re the manager

We start learning management skills from a fairly early age. You manage your time, your money, your day-to-day living. But when it comes to running a business, you need to step it up. Now you’re managing clients, with their budgets, deadlines, and expectations. And every client is different. Get it wrong, and you lose out.

I was managing a Nigerian client on an identity design project when, after creating a wordmark, I agreed to design and supply the artwork for corporate stationery at no extra charge. Having sent the print-ready files, I was asked to change the contact details (address, phone numbers, etc.) on two different occasions—details that should have been correct the first time around. Some weeks later, I was asked to create additional business card files for two new employees. When I responded with an invoice for my absolute minimum charge, my client wanted me to work for less than half that price. I refused, explaining that it was unsustainable to do so, but that I understood how I had placed myself in this awkward scenario by having given my work away for free.

I never heard from that client again.

The lesson? When you give a client something for free, you send the signal that everything will be free (or at least hugely discounted). And that’s bad management.

Motivate yourself

When my wife has a day off work, her morning is usually spent lying in. So during the short winter days, when it doesn’t get bright until around 9 a.m., when the house is a lot colder than normal, and with no boss waiting for me at the office by a set time, it takes a good deal of discipline to pull myself out of a warm bed.

What helps make it worthwhile are the wonderful emails I receive from aspiring designers all around the world. Barely a day goes by when I don’t receive at least one, telling me how my blogs or my book Logo Design Love (New Riders, 2010) have helped them through their studies or given them the confidence to work at what they love. I don’t say this to boast. I am telling you this because it is a huge source of motivation for me. You need to look for what consistently inspires you. (We’ll take a more detailed look at setting up your blog in chapter 10, and at writing a book in chapter 20.)

Another motivational tool I use is the life into which I was born. I have two loving parents who remained together for 30-plus years to provide a stable home life for me, my brother, and my sister. I always had a roof over my head. I was never left hungry. I was afforded a great education through primary school, secondary school, college, and university. My family has always been supportive about what I want to do.

Too few children have these same luxuries. I owe it to my family to make the most of my time here, and I owe it to my future children—if I’m fortunate enough to have any—to provide them with the opportunities I was given.

Professionalism

It’s called the design profession because it’s full of design professionals. So you’d assume that acting in a professional manner was the obvious path. However, time and time again, I see fellow professionals failing to act professionally; for instance, masking their portfolio work with all the latest Web bells and whistles, or showing artwork without any context or description.

Look at how the most well-known, well-respected design studios present themselves. Chermayeff & Geismar, Moving Brands, Pentagram, Wolff Olins, Landor, Turner Duckworth, venturethree, SomeOne, johnson banks. Their websites are easy to navigate, they make it easy to contact them, and the focus is strongly on their client work, shown in context.

The copy on your website, the way you answer the phone, the time it takes you to reply to emails, the way you dress—even if you work from home, alone—these and a hundred other little details all added together are what make all the difference. Think of it like a healthy marriage—you fill the years with endless little loving gestures, rather than a single, big, dramatic event surrounded by years of disappointments.

Dublin-based designer Con Kennedy received a phone call out of the blue from a potential client asking him to “throw a few ideas together.” Con replied by saying that he didn’t throw ideas together, but that he’d supply a written document outlining his proposed solution with a breakdown of the costs. The very next day he received a call telling him the proposal was very professional. The client is now Con’s most loyal, supplying him with work that has included storyboarding his first TV ad, regular commissions for front-end user interface design for websites, exhibition and tradeshow design, and iPhone app design. Acting professionally pays off.

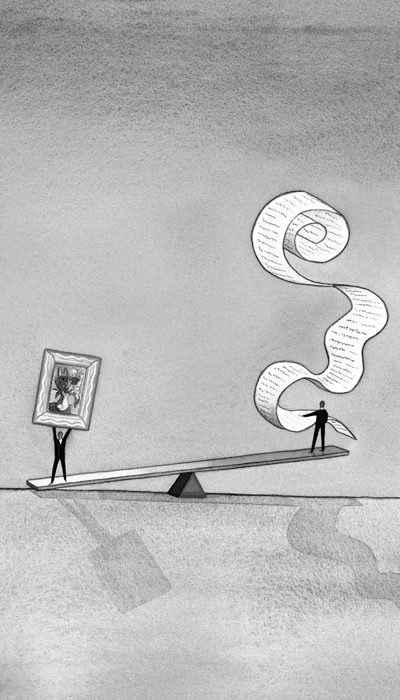

Balance

Your working hours are going to increase, but your interest levels will skyrocket. That’s the trade-off when you become self-employed.

It’s worth it.

Trust me.

The word “work” has a certain stigma attached to it. But designers are more fortunate than most. We love what we do. To us, our job seems head and shoulders above long shifts in a hot kitchen, or walking the mean streets late at night keeping the peace. But there are chefs and police officers who love their professions, too. When you love what you do, it’s not like work.

That’s fantastic, but when we’re that happy, soon sleep is treated as an interruption and our loved ones are given a back seat in our lives.

That’s where balance is vital.

What’s a good trade-off to you might be a bad one to someone else. In the words of John Maeda, president of Rhode Island School of Design, “Balance isn’t about achieving 50/50. It’s about oscillating around a desired norm—knowing that results may vary.”

Stefan Sagmeister is one designer putting balance into practice. Every seven years he closes his New York studio and takes a year-long sabbatical. Think of it as if he intersperses his life with the retirement years he’s due, except he’s younger and more mobile now, and can use his sabbatical experiences to feed his upcoming work.

For me, it’s hard to beat playing football with my friends each week. Fresh air. Exercise. Competition. Banter. Scoring goals.

Don’t blindly trust your experience

Experience dominates our thought process. That’s why children have such vivid imaginations—they’re inexperienced. If you can free yourself from what you’ve done before, you open up a world of possibility.

At the 2011 Design Indaba in the Cape Town International Convention Centre, Michael Wolff, cofounder of Wolff Olins, spoke about how to exercise your idea-creating capacity by first getting rid of your ideas. “I mistrust my experience in terms of using my imagination; it’s going to miscolor it, try to dominate it.”

To quote American graphic designer Bob Gill, “A designer who knows what a solution should look like, before he knows the problem, is as ridiculous as a mathematician who knows the answer is 112 before he knows the question.”

When I accept a fresh project, I treat it like a new learning experience by first researching the basics of my client’s business. I look at the simplest ways in which a profit is made and the simplest goals of the business. What I don’t do is consider implementing unused designs from previous client projects. There are an increasing number of websites springing up that aim to make a profit off of designers selling their unused ideas. It’s a case of designers wanting to be paid twice (first by their original client, then by a never-to-be-seen client picking design off a shelf), and the client looking for previously rejected ideas. Hardly inspirational.

Don’t forget to...

...smile. It’s difficult to argue with the ways of the ancient Chinese. There’s a particular proverb that’s worth pinning to your wall:

“A man without a smiling face must not open a shop.”

Good advice.

When clients initially approach me, it’s mainly via email after reading my blog or viewing my online portfolio. Most of my clients have never seen me face to face. They’ve never talked to me on the phone. They’re sending a message into the void with the aim of spending a significant amount of money to hire me. Put yourself in their shoes. You’d be a little nervous, apprehensive, unsure—especially if it was your first time working with a designer.

A new client will often email back and forth with me a bit to gauge if we’re a good fit, and the next step is usually talking on the phone.

When you lift your cheek muscles and smile, the soft palate at the back of your mouth raises and makes the sound waves more fluid. The result is that your voice sounds warmer and more friendly, exactly the impression you want to give to a potential client. Conversely, when you frown, your voice sounds colder and more harsh.

Smiling works and it costs nothing; I’ve won thousands of dollars worth of business after talking on the phone, wearing a smile that the client can’t see, but can hear.