Five. Disappearing Diversification

What can investors learn from a lemonade stand?

Think back to that summer lemonade stand you operated as a kid. On hot sunny days you couldn’t keep up with demand from neighborhood children, parents’ yard work, or teenagers developing their tans. But what about the long winter days when everyone was trapped inside? Were you forced to wait out weeks or months of the season with no profits? Success was largely dependent on the uncontrollable variables of temperature and the climate in which you operated. If you only offered lemonade, you probably only made money on sunny days.

But what if you offered an alternative, one suited to the changing seasons? Perhaps you opened a hot chocolate stand where everyone was sledding? By branching out with diverse offerings, you had the potential to earn a profit year round, regardless of the weather.

Individuals can’t control the weather any more than investors can control globalization, regulations, unexpected events, new innovations, or human behavior. And since we can’t change market inputs, maybe it’s time we changed the way we invest (remember that investing has inherent risks, and a change in strategy will not guarantee better results).

If we’re going to change our strategies, we need to understand why we make the financial choices we do. This is the question proponents of behavioral finance, including Princeton professor and Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman, have been trying to answer for decades. In 1979, Kahneman wrote a widely regarded paper with Amos Tversky on the subject of behavioral economics that introduced the phrase “prospect theory.”71 “If you want an easy introduction to behavioral economics, it’s economics without making the assumption that [investors] are fully rational or that they have perfect self-control,” Kahneman told AdvisorOne in late 2011.72 Specifically, behavioral finance identifies the psychological reasons investors make decisions, reasons of which they are often unaware.

71 Floris Heukelom, Amsterdam School of Economics, “Kahneman and Tversky and the Origin of Behavioral Economics,” May 2006.

72 John Sullivan, AdvisorOne, “Behavioral Economics: Your Own Worst Enemy,” January 2012.

Sugary Sweet: Learning Self-Control

Kahneman’s work identifies two primary investor traits that inadvertently harm long-term portfolio performance: hope for gain and fear of loss,73 known as the aforementioned prospect theory. It’s the idea that fear originates not only in our desire to avoid investment loss, but also, to a lesser extent, to avoid missing out on potential gain. I believe the now legendary collapse of energy firm Enron at the beginning of the last decade is an excellent example of prospect theory.

73 Investopedia, “Prospect Theory,” 2013.

Throughout the bull market of the 1980s and 1990s, many companies saw their stock prices skyrocket. This may have caused employees to overinvest in their companies’ stock plans, thinking the stock would continue to rise into perpetuity, or perhaps they believed that since they worked at that particular company, they would recognize signs of potential danger and divest in time. Personally, I think it was the influence of fear and greed.

Consider the bankruptcy of Enron. Employees were more focused on their portfolio statements than the shoddy theories fueling their returns. This was demonstrated by an extremely high adoption rate among its staff in the stock ownership plan offered by the company, with some employees investing 100% of their retirement funds. Even when troubles began to emerge, many held on to stock, afraid to miss out on potential gains.74 For that reason, diversification didn’t seem to matter.

74 Christine Dugas, USA Today, “Energy Giant’s Disaster Devastates 401(k) Plans,” November 2001.

As the company imploded, management eventually instituted a “temporary freeze,” preventing employees from selling their stock in an effort to slow the descent. By the time the freeze was lifted, the company was on the verge of collapse and the stock was virtually worthless.75

75 Christine Dugas, USA Today, “Employees’ Faith in Enron Cost Them Life Savings,” January 2002.

Of course the public outcry at the financial malfeasance of Enron CEOs was intense and widespread. At the same time, I would say that former Enron employees became the poster children for the dangers of not employing a diversified plan.

You hope investors would learn, but how many tragic tales were aired in the wake of the Ponzi scheme perpetrated by Bernie Madoff, in which retires lost their homes, moved in with their children, or were forced back to work?

But diversification is more than simply investing in different companies. Investors seeking to diversify their portfolio also must look at how connected, or correlated, their investments are. Today there is a myriad of investment options and vehicles used to lower correlation in a portfolio. While diversification and lack of correlation do not necessarily remove risk and losses can still be incurred, diversification is an important investment strategy. But with so many options, how does an investor know the right way to go?

Similar Taste: The Rise of Correlation

Probably the greatest consideration for including alternative investments in a portfolio is the rise in correlation in recent years. As I briefly discussed in earlier chapters, the term correlation, as it refers to stock market performance, asset classes, or sectors, is a measure of how likely they are to move in either the same or opposite direction. If they are positively correlated, they will move in lock step with one another, either by rising or falling together, which is precisely the problem. When one falls, the other is likely to follow.

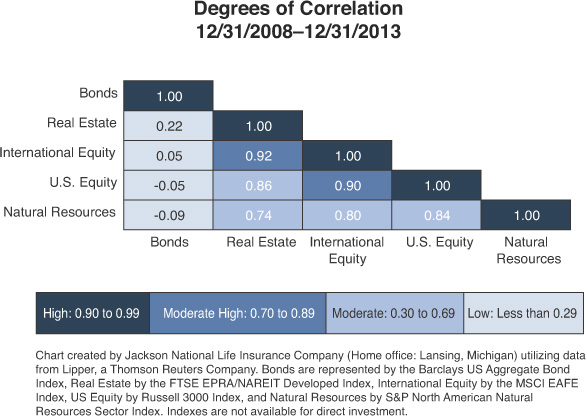

Correlation is a market-driven outcome that directly affects the benefits of diversification. Higher correlations are an indication of lower diversification. For example, you can see by the matrix in Figure 5.1 that U.S. equity, as measured by the Russell 3000, and international equity, as measured by the MSCI EAFE (an index that measures equity performance in developed markets outside the United States and Canada), have a high correlation of 0.90.76

76 Lipper, a Thomson Reuters Company, January 2014.

Zooming into the correlation between U.S. and international equity, in 10-year increments, over the last 30 years (ended 12/31/2013) we’ve also seen the correlation between U.S. and international stocks almost double, from 0.43 to 0.89,77 as can be seen in Figure 5.2.

77 Ibid.

The increase in international correlation is partially a result of the reduction of trade barriers and improved political environments that came about after the end of the Cold War. In the same way global economies are becoming more interconnected, multinational corporations are also increasingly dependent on international sales. For example, Coca-Cola® (which is based in Atlanta) is “...one of the most globally active international companies, derived 80 percent of its sales from outside the U.S.”78 Conversely, Samsung®, a Korean-based company, had 47 percent of its sales in America in 2011.79

78 William J. Holstein, Strategy+Business, “How Coca-Cola Manages 90 Emerging Markets,” November 2011.

79 Samsung Electronics, “Sustainability Report,” 2012.

According to Morningstar© 2014 Morningstar, Inc.,* this rise in correlation isn’t confined to individual stocks. Companies in the same industries that together comprise many of the S&P 500 sectors have also become more highly correlated within the S&P 500 Index. Between 1994 and 2008, 69% of the average monthly returns of the investment sectors included in the index were correlated, meaning they moved in tandem. In the four years since, that number has increased to 84%. Morningstar notes that no decline in correlation was seen in any of the S&P 500 Index’s 10 sectors. Even utilities, the least correlated sector, rose from 38% to 67%. More concerning, correlation between large-cap and small-cap stocks in 2012 was at its highest level in 60 years.80

* All Rights Reserved. The information contained herein: (1) is proprietary to Morningstar and/or its content providers; (2) may not be copied or distributed; (3) does not constitute investment advice offered by Morningstar; and (4) is not warranted to be accurate, complete or timely. Neither Morningstar nor its content providers are responsible for any damages or losses arising from any use of this information. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Use of information from Morningstar does not necessarily constitute agreement by Morningstar, Inc. of any investment philosophy or strategy presented in this publication

80 Michael Rawson, Morningstar, “The Correlation Conundrum and What to Do About It,” May 9, 2012.

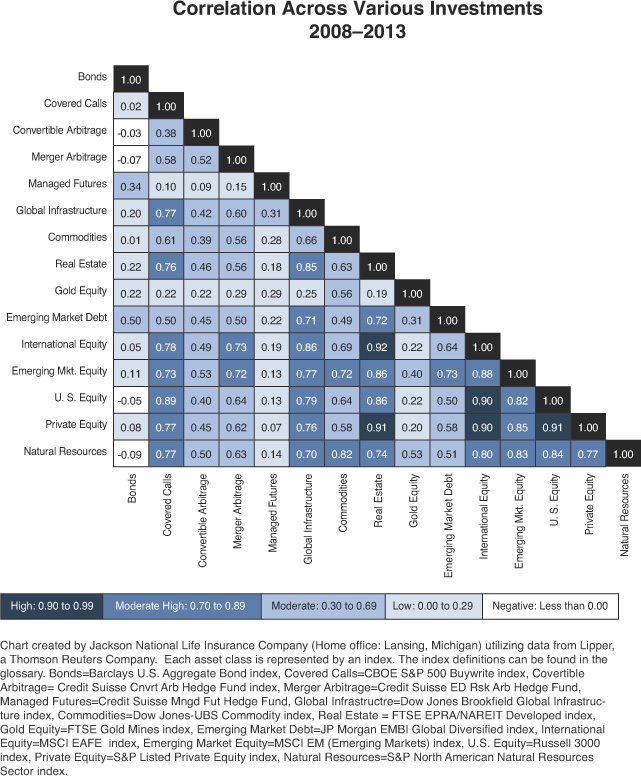

Investors may think they are properly diversified by investing in different companies, sectors, and even countries around the globe, and honestly, who could blame them? The distressing fact is, increasingly they are not, something of which they are too often unaware. Yet as correlation decreases, so too does the possibility of its corresponding risk in the portfolio. Alternative investments are not only moderately to lowly correlated to traditional stocks and bonds, they’re also not very correlated with each other (as the “Correlations Across Various Investments” chart in Figure 5.3 illustrates).

Proper Diversification: A Well-Balanced Diet

Asset allocation and proper diversification mean different things to different people, but the important lesson is to not concentrate your portfolio in any one vehicle or investment type. Think of it in terms of a balanced diet. What constitutes “balanced” will depend on a person’s age, height, weight, medical situation, allergies, and other characteristics specific to the individual. But one thing is certain: a diet that only consisted of breads and cereals would not be considered healthy. And so it is with a person’s investment portfolio—the individual’s allocation of assets will depend on age, goals, years to retirement, and other factors.

In my opinion, the need for proper diversification within the portfolio will only continue to increase, and it is happening at exactly the same time our “interconnected world” is making it that much harder for the everyday investor to achieve due to increasing correlation.

Thirst for Diversification: Develop an All-Weather Strategy

What this means is that an international and domestic strategy for sunny and rainy days, in good markets and bad, plays a big role in investor success. I feel strongly that alternative investments can play a significant role in that strategy. By helping to provide further diversification due to their historically low correlation to traditional investments, they can help the portfolio by moving independently of stocks, bonds, and each other, through changing climates.

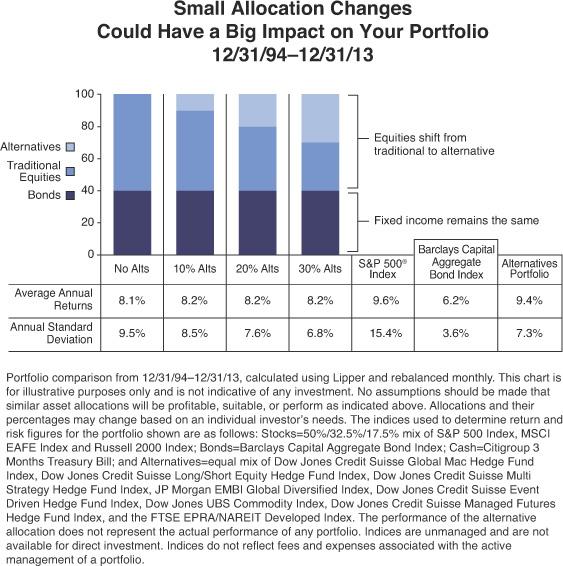

The accompanying graph in Figure 5.4 illustrates how making a minor tweak in a portfolio by adding alternative investments increased returns and lowered risk. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. As you can see, when the allocation to alternatives in the portfolio increased, average annual returns went up and annual standard deviation (also known as risk) went down.

Although asset allocation among different asset categories generally limits exposure to any one category, the risk remains that an asset category that performs poorly relative to the other asset categories may be favored. Other investment risks include general economic risk, geopolitical risk, commodity-price volatility, counterparty and settlement risk, currency risk, derivatives risk, emerging markets risk, foreign securities risk, high-yield bond exposure, noninvestment-grade bond exposure, index investing risk, industry concentration risk, leveraging risk, market risk, prepayment risk, liquidity risk, real estate investment risk, sector risk, short sales risk, temporary defensive positions, and large cash positions. Diversification does not assure a profit or protect against loss in a declining market. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Alternatives may also negate the benefits of diversification.

From the Alt Vault: Valuable Takeaways from Chapter Five

The important lesson is not to concentrate the portfolio in any one vehicle or investment type. Just like the best lemonade is a combination of several key ingredients, a well-balanced portfolio may incorporate many different opportunities. Alternatives are one way investors can diversify their portfolio.

![]() Markets cannot be controlled, however, investors can control their reaction to them.

Markets cannot be controlled, however, investors can control their reaction to them.

![]() Fear and greed can lead to poor judgment.

Fear and greed can lead to poor judgment.

![]() Individual stocks and markets are becoming increasingly correlated.

Individual stocks and markets are becoming increasingly correlated.

![]() In our interconnected world, portfolios need balance.

In our interconnected world, portfolios need balance.

![]() Develop a strategy for sunny and rainy days; consider one that includes alternative investments to help manage the volatility.

Develop a strategy for sunny and rainy days; consider one that includes alternative investments to help manage the volatility.

What’s next: How do institutional investors build their portfolios? Where do they get their ideas? Where are their sights set now?