1

WHAT IS DESIGN AND ARCHITECTURE?

There has been a lot of confusion about design and architecture over the years. What is design? What is architecture? What are the differences between the two?

One of the goals of this book is to cut through all that confusion and to define, once and for all, what design and architecture are. For starters, I’ll assert that there is no difference between them. None at all.

The word “architecture” is often used in the context of something at a high level that is divorced from the lower-level details, whereas “design” more often seems to imply structures and decisions at a lower level. But this usage is nonsensical when you look at what a real architect does.

Consider the architect who designed my new home. Does this home have an architecture? Of course it does. And what is that architecture? Well, it is the shape of the home, the outward appearance, the elevations, and the layout of the spaces and rooms. But as I look through the diagrams that my architect produced, I see an immense number of low-level details. I see where every outlet, light switch, and light will be placed. I see which switches control which lights. I see where the furnace is placed, and the size and placement of the water heater and the sump pump. I see detailed depictions of how the walls, roofs, and foundations will be constructed.

In short, I see all the little details that support all the high-level decisions. I also see that those low-level details and high-level decisions are part of the whole design of the house.

And so it is with software design. The low-level details and the high-level structure are all part of the same whole. They form a continuous fabric that defines the shape of the system. You can’t have one without the other; indeed, no clear dividing line separates them. There is simply a continuum of decisions from the highest to the lowest levels.

THE GOAL?

And the goal of those decisions? The goal of good software design? That goal is nothing less than my utopian description:

The goal of software architecture is to minimize the human resources required to build and maintain the required system.

The measure of design quality is simply the measure of the effort required to meet the needs of the customer. If that effort is low, and stays low throughout the lifetime of the system, the design is good. If that effort grows with each new release, the design is bad. It’s as simple as that.

CASE STUDY

As an example, consider the following case study. It includes real data from a real company that wishes to remain anonymous.

First, let’s look at the growth of the engineering staff. I’m sure you’ll agree that this trend is very encouraging. Growth like that shown in Figure 1.1 must be an indication of significant success!

Figure 1.1 Growth of the engineering staff

Reproduced with permission from a slide presentation by Jason Gorman

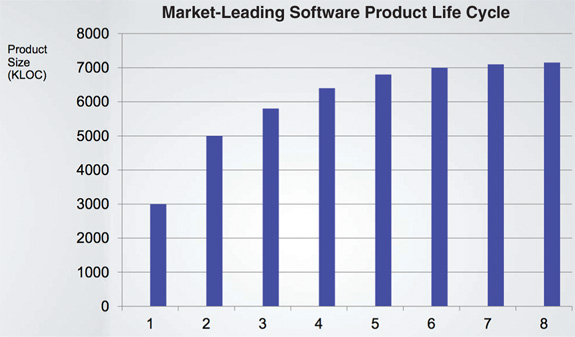

Now let’s look at the company’s productivity over the same time period, as measured by simple lines of code (Figure 1.2).

Clearly something is going wrong here. Even though every release is supported by an ever-increasing number of developers, the growth of the code looks like it is approaching an asymptote.

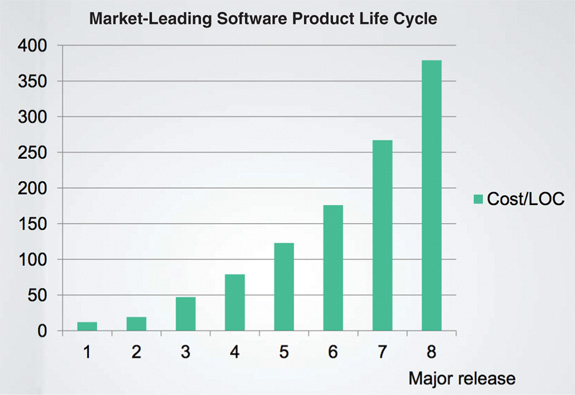

Now here’s the really scary graph: Figure 1.3 shows how the cost per line of code has changed over time.

These trends aren’t sustainable. It doesn’t matter how profitable the company might be at the moment: Those curves will catastrophically drain the profit from the business model and drive the company into a stall, if not into a downright collapse.

What caused this remarkable change in productivity? Why was the code 40 times more expensive to produce in release 8 as opposed to release 1?

THE SIGNATURE OF A MESS

What you are looking at is the signature of a mess. When systems are thrown together in a hurry, when the sheer number of programmers is the sole driver of output, and when little or no thought is given to the cleanliness of the code or the structure of the design, then you can bank on riding this curve to its ugly end.

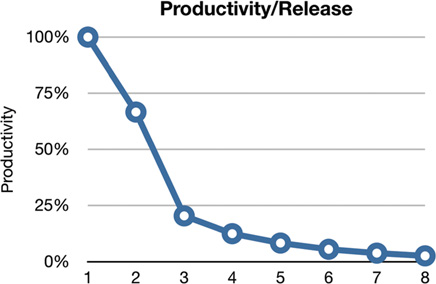

Figure 1.4 shows what this curve looks like to the developers. They started out at nearly 100% productivity, but with each release their productivity declined. By the fourth release, it was clear that their productivity was going to bottom out in an asymptotic approach to zero.

From the developers’ point of view, this is tremendously frustrating, because everyone is working hard. Nobody has decreased their effort.

And yet, despite all their heroics, overtime, and dedication, they simply aren’t getting much of anything done anymore. All their effort has been diverted away from features and is now consumed with managing the mess. Their job, such as it is, has changed into moving the mess from one place to the next, and the next, and the next, so that they can add one more meager little feature.

THE EXECUTIVE VIEW

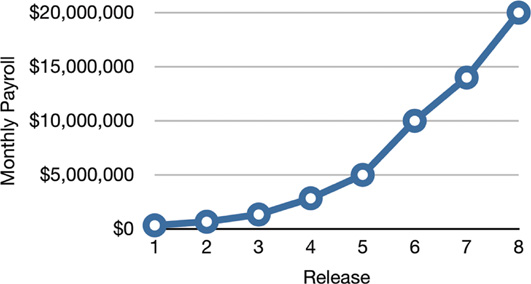

If you think that’s bad, imagine what this picture looks like to the executives! Consider Figure 1.5, which depicts monthly development payroll for the same period.

Release 1 was delivered with a monthly payroll of a few hundred thousand dollars. The second release cost a few hundred thousand more. By the eighth release monthly payroll was $20 million, and climbing.

Just this chart alone is scary. Clearly something startling is happening. One hopes that revenues are outpacing costs and therefore justifying the expense. But no matter how you look at this curve, it’s cause for concern.

But now compare the curve in Figure 1.5 with the lines of code written per release in Figure 1.2. That initial few hundred thousand dollars per month bought a lot of functionality—but the final $20 million bought almost nothing! Any CFO would look at these two graphs and know that immediate action is necessary to stave off disaster.

But which action can be taken? What has gone wrong? What has caused this incredible decline in productivity? What can executives do, other than to stamp their feet and rage at the developers?

WHAT WENT WRONG?

Nearly 2600 years ago, Aesop told the story of the Tortoise and the Hare. The moral of that story has been stated many times in many different ways:

• “Slow and steady wins the race.”

• “The race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong.”

• “The more haste, the less speed.”

The story itself illustrates the foolishness of overconfidence. The Hare, so confident in its intrinsic speed, does not take the race seriously, and so naps while the Tortoise crosses the finish line.

Modern developers are in a similar race, and exhibit a similar overconfidence. Oh, they don’t sleep—far from it. Most modern developers work their butts off. But a part of their brain does sleep—the part that knows that good, clean, well-designed code matters.

These developers buy into a familiar lie: “We can clean it up later; we just have to get to market first!” Of course, things never do get cleaned up later, because market pressures never abate. Getting to market first simply means that you’ve now got a horde of competitors on your tail, and you have to stay ahead of them by running as fast as you can.

And so the developers never switch modes. They can’t go back and clean things up because they’ve got to get the next feature done, and the next, and the next, and the next. And so the mess builds, and productivity continues its asymptotic approach toward zero.

Just as the Hare was overconfident in its speed, so the developers are overconfident in their ability to remain productive. But the creeping mess of code that saps their productivity never sleeps and never relents. If given its way, it will reduce productivity to zero in a matter of months.

The bigger lie that developers buy into is the notion that writing messy code makes them go fast in the short term, and just slows them down in the long term. Developers who accept this lie exhibit the hare’s overconfidence in their ability to switch modes from making messes to cleaning up messes sometime in the future, but they also make a simple error of fact. The fact is that making messes is always slower than staying clean, no matter which time scale you are using.

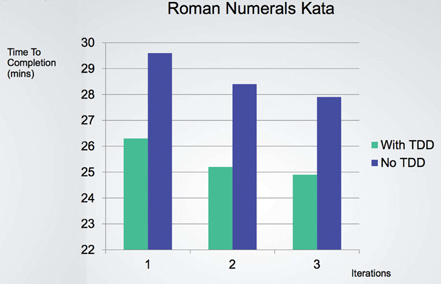

Consider the results of a remarkable experiment performed by Jason Gorman depicted in Figure 1.6. Jason conducted this test over a period of six days. Each day he completed a simple program to convert integers into Roman numerals. He knew his work was complete when his predefined set of acceptance tests passed. Each day the task took a little less than 30 minutes. Jason used a well-known cleanliness discipline named test-driven development (TDD) on the first, third, and fifth days. On the other three days, he wrote the code without that discipline.

First, notice the learning curve apparent in Figure 1.6. Work on the latter days is completed more quickly than the former days. Notice also that work on the TDD days proceeded approximately 10% faster than work on the non-TDD days, and that even the slowest TDD day was faster than the fastest non-TDD day.

Some folks might look at that result and think it’s a remarkable outcome. But to those who haven’t been deluded by the Hare’s overconfidence, the result is expected, because they know this simple truth of software development:

The only way to go fast, is to go well.

And that’s the answer to the executive’s dilemma. The only way to reverse the decline in productivity and the increase in cost is to get the developers to stop thinking like the overconfident Hare and start taking responsibility for the mess that they’ve made.

The developers may think that the answer is to start over from scratch and redesign the whole system—but that’s just the Hare talking again. The same overconfidence that led to the mess is now telling them that they can build it better if only they can start the race over. The reality is less rosy:

Their overconfidence will drive the redesign into the same mess as the original project.

CONCLUSION

In every case, the best option is for the development organization to recognize and avoid its own overconfidence and to start taking the quality of its software architecture seriously.

To take software architecture seriously, you need to know what good software architecture is. To build a system with a design and an architecture that minimize effort and maximize productivity, you need to know which attributes of system architecture lead to that end.

That’s what this book is about. It describes what good clean architectures and designs look like, so that software developers can build systems that will have long profitable lifetimes.