10

ISP: THE INTERFACE SEGREGATION PRINCIPLE

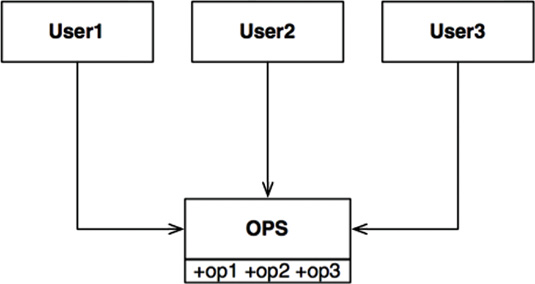

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) derives its name from the diagram shown in Figure 10.1.

In the situation illustrated in Figure 10.1, there are several users who use the operations of the OPS class. Let’s assume that User1 uses only op1, User2 uses only op2, and User3 uses only op3.

Now imagine that OPS is a class written in a language like Java. Clearly, in that case, the source code of User1 will inadvertently depend on op2 and op3, even though it doesn’t call them. This dependence means that a change to the source code of op2 in OPS will force User1 to be recompiled and redeployed, even though nothing that it cared about has actually changed.

This problem can be resolved by segregating the operations into interfaces as shown in Figure 10.2.

Again, if we imagine that this is implemented in a statically typed language like Java, then the source code of User1 will depend on U1Ops, and op1, but will not depend on OPS. Thus a change to OPS that User1 does not care about will not cause User1 to be recompiled and redeployed.

ISP AND LANGUAGE

Clearly, the previously given description depends critically on language type. Statically typed languages like Java force programmers to create declarations that users must import, or use, or otherwise include. It is these included declarations in source code that create the source code dependencies that force recompilation and redeployment.

In dynamically typed languages like Ruby and Python, such declarations don’t exist in source code. Instead, they are inferred at runtime. Thus there are no source code dependencies to force recompilation and redeployment. This is the primary reason that dynamically typed languages create systems that are more flexible and less tightly coupled than statically typed languages.

This fact could lead you to conclude that the ISP is a language issue, rather than an architecture issue.

ISP AND ARCHITECTURE

If you take a step back and look at the root motivations of the ISP, you can see a deeper concern lurking there. In general, it is harmful to depend on modules that contain more than you need. This is obviously true for source code dependencies that can force unnecessary recompilation and redeployment—but it is also true at a much higher, architectural level.

Consider, for example, an architect working on a system, S. He wants to include a certain framework, F, into the system. Now suppose that the authors of F have bound it to a particular database, D. So S depends on F. which depends on D (Figure 10.3).

Now suppose that D contains features that F does not use and, therefore, that S does not care about. Changes to those features within D may well force the redeployment of F and, therefore, the redeployment of S. Even worse, a failure of one of the features within D may cause failures in F and S.

CONCLUSION

The lesson here is that depending on something that carries baggage that you don’t need can cause you troubles that you didn’t expect.

We’ll explore this idea in more detail when we discuss the Common Reuse Principle in Chapter 13, “Component Cohesion.”