18

BOUNDARY ANATOMY

The architecture of a system is defined by a set of software components and the boundaries that separate them. Those boundaries come in many different forms. In this chapter we’ll look at some of the most common.

BOUNDARY CROSSING

At runtime, a boundary crossing is nothing more than a function on one side of the boundary calling a function on the other side and passing along some data. The trick to creating an appropriate boundary crossing is to manage the source code dependencies.

Why source code? Because when one source code module changes, other source code modules may have to be changed or recompiled, and then redeployed. Managing and building firewalls against this change is what boundaries are all about.

THE DREADED MONOLITH

The simplest and most common of the architectural boundaries has no strict physical representation. It is simply a disciplined segregation of functions and data within a single processor and a single address space. In a previous chapter, I called this the source-level decoupling mode.

From a deployment point of view, this amounts to nothing more than a single executable file—the so-called monolith. This file might be a statically linked C or C++ project, a set of Java class files bound together into an executable jar file, a set of .NET binaries bound into a single .EXE file, and so on.

The fact that the boundaries are not visible during the deployment of a monolith does not mean that they are not present and meaningful. Even when statically linked into a single executable, the ability to independently develop and marshal the various components for final assembly is immensely valuable.

Such architectures almost always depend on some kind of dynamic polymorphism1 to manage their internal dependencies. This is one of the reasons that object-oriented development has become such an important paradigm in recent decades. Without OO, or an equivalent form of polymorphism, architects must fall back on the dangerous practice of using pointers to functions to achieve the appropriate decoupling. Most architects find prolific use of pointers to functions to be too risky, so they are forced to abandon any kind of component partitioning.

The simplest possible boundary crossing is a function call from a low-level client to a higher-level service. Both the runtime dependency and the compile-time dependency point in the same direction, toward the higher-level component.

In Figure 18.1, the flow of control crosses the boundary from left to right. The Client calls function f() on the Service. It passes along an instance of Data. The <DS> marker simply indicates a data structure. The Data may be passed as a function argument or by some other more elaborate means. Note that the definition of the Data is on the called side of the boundary.

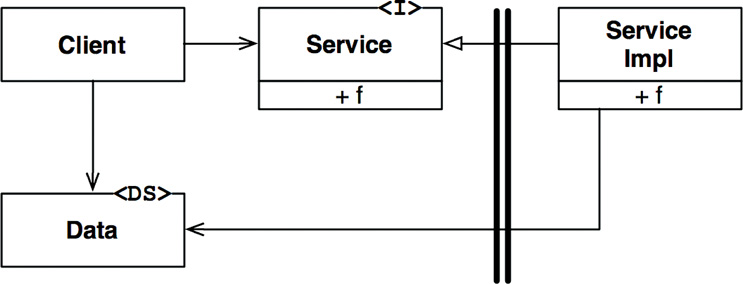

When a high-level client needs to invoke a lower-level service, dynamic polymorphism is used to invert the dependency against the flow of control. The runtime dependency opposes the compile-time dependency.

In Figure 18.2, the flow of control crosses the boundary from left to right as before. The high-level Client calls the f() function of the lower-level ServiceImpl through the Service interface. Note, however, that all dependencies cross the boundary from right to left toward the higher-level component. Note, also, that the definition of the data structure is on the calling side of the boundary.

Even in a monolithic, statically linked executable, this kind of disciplined partitioning can greatly aid the job of developing, testing, and deploying the project. Teams can work independently of each other on their own components without treading on each other’s toes. High-level components remain independent of lower-level details.

Communications between components in a monolith are very fast and inexpensive. They are typically just function calls. Consequently, communications across source-level decoupled boundaries can be very chatty.

Since the deployment of monoliths usually requires compilation and static linking, components in these systems are typically delivered as source code.

DEPLOYMENT COMPONENTS

The simplest physical representation of an architectural boundary is a dynamically linked library like a .Net DLL, a Java jar file, a Ruby Gem, or a UNIX shared library. Deployment does not involve compilation. Instead, the components are delivered in binary, or some equivalent deployable form. This is the deployment-level decoupling mode. The act of deployment is simply the gathering of these deployable units together in some convenient form, such as a WAR file, or even just a directory.

With that one exception, deployment-level components are the same as monoliths. The functions generally all exist in the same processor and address space. The strategies for segregating the components and managing their dependencies are the same.2

As with monoliths, communications across deployment component boundaries are just function calls and, therefore, are very inexpensive. There may be a one-time hit for dynamic linking or runtime loading, but communications across these boundaries can still be very chatty.

THREADS

Both monoliths and deployment components can make use of threads. Threads are not architectural boundaries or units of deployment, but rather a way to organize the schedule and order of execution. They may be wholly contained within a component, or spread across many components.

LOCAL PROCESSES

A much stronger physical architectural boundary is the local process. A local process is typically created from the command line or an equivalent system call. Local processes run in the same processor, or in the same set of processors within a multicore, but run in separate address spaces. Memory protection generally prevents such processes from sharing memory, although shared memory partitions are often used.

Most often, local processes communicate with each other using sockets, or some other kind of operating system communications facility such as mailboxes or message queues.

Each local process may be a statically linked monolith, or it may be composed of dynamically linked deployment components. In the former case, several monolithic processes may have the same components compiled and linked into them. In the latter, they may share the same dynamically linked deployment components.

Think of a local process as a kind of uber-component: The process consists of lower-level components that manage their dependencies through dynamic polymorphism.

The segregation strategy between local processes is the same as for monoliths and binary components. Source code dependencies point in the same direction across the boundary, and always toward the higher-level component.

For local processes, this means that the source code of the higher-level processes must not contain the names, or physical addresses, or registry lookup keys of lower-level processes. Remember that the architectural goal is for lower-level processes to be plugins to higher-level processes.

Communication across local process boundaries involve operating system calls, data marshaling and decoding, and interprocess context switches, which are moderately expensive. Chattiness should be carefully limited.

SERVICES

The strongest boundary is a service. A service is a process, generally started from the command line or through an equivalent system call. Services do not depend on their physical location. Two communicating services may, or may not, operate in the same physical processor or multicore. The services assume that all communications take place over the network.

Communications across service boundaries are very slow compared to function calls. Turnaround times can range from tens of milliseconds to seconds. Care must be taken to avoid chatting where possible. Communications at this level must deal with high levels of latency.

Otherwise, the same rules apply to services as apply to local processes. Lower-level services should “plug in” to higher-level services. The source code of higher-level services must not contain any specific physical knowledge (e.g., a URI) of any lower-level service.

CONCLUSION

Most systems, other than monoliths, use more than one boundary strategy. A system that makes use of service boundaries may also have some local process boundaries. Indeed, a service is often just a facade for a set of interacting local processes. A service, or a local process, will almost certainly be either a monolith composed of source code components or a set of dynamically linked deployment components.

This means that the boundaries in a system will often be a mixture of local chatty boundaries and boundaries that are more concerned with latency.

1. Static polymorphism (e.g., generics or templates) can sometimes be a viable means of dependency management in monolithic systems, especially in languages like C++. However, the decoupling afforded by generics cannot protect you from the need for recompilation and redeployment the way dynamic polymorphism can.

2. Although static polymorphism is not an option in this case.