29

CLEAN EMBEDDED ARCHITECTURE

By James Grenning

A while ago I read an article entitled “The Growing Importance of Sustaining Software for the DoD”1 on Doug Schmidt’s blog. Doug made the following claim:

“Although software does not wear out, firmware and hardware become obsolete, thereby requiring software modifications.”

It was a clarifying moment for me. Doug mentioned two terms that I would have thought to be obvious—but maybe not. Software is this thing that can have a long useful life, but firmware will become obsolete as hardware evolves. If you have spent any time in embedded systems development, you know the hardware is continually evolving and being improved. At the same time, features are added to the new “software,” and it continually grows in complexity.

I’d like to add to Doug’s statement:

Although software does not wear out, it can be destroyed from within by unmanaged dependencies on firmware and hardware.

It is not uncommon for embedded software to be denied a potentially long life due to being infected with dependencies on hardware.

I like Doug’s definition of firmware, but let’s see which other definitions are out there. I found these alternatives:

• “Firmware is held in non-volatile memory devices such as ROM, EPROM, or flash memory.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Firmware)

• “Firmware is a software program or set of instructions programmed on a hardware device.” (https://techterms.com/definition/firmware)

• “Firmware is software that is embedded in a piece of hardware.” (https://www.lifewire.com/what-is-firmware-2625881)

• Firmware is “Software (programs or data) that has been written onto read-only memory (ROM).” (http://www.webopedia.com/TERM/F/firmware.html)

Doug’s statement makes me realize that these accepted definitions of firmware are wrong, or at least obsolete. Firmware does not mean code lives in ROM. It’s not firmware because of where it is stored; rather, it is firmware because of what it depends on and how hard it is to change as hardware evolves. Hardware does evolve (pause and look at your for phone for evidence), so we should structure our embedded code with that reality in mind.

I have nothing against firmware, or firmware engineers (I’ve been known to write some firmware myself). But what we really need is less firmware and more software. Actually, I am disappointed that firmware engineers write so much firmware!

Non-embedded engineers also write firmware! You non-embedded developers essentially write firmware whenever you bury SQL in your code or when you spread platform dependencies throughout your code. Android app developers write firmware when they don’t separate their business logic from the Android API.

I’ve been involved in a lot of efforts where the line between the product code (the software) and the code that interacts with the product’s hardware (the firmware) is fuzzy to the point of nonexistence. For example, in the late 1990s I had the fun of helping redesign a communications subsystem that was transitioning from time-division multiplexing (TDM) to voice over IP (VOIP). VOIP is how things are done now, but TDM was considered the state of the art from the 1950s and 1960s, and was widely deployed in the 1980s and 1990s.

Whenever we had a question for the systems engineer about how a call should react to a given situation, he would disappear and a little later emerge with a very detailed answer. “Where did he get that answer?” we asked. “From the current product’s code,” he’d answer. The tangled legacy code was the spec for the new product! The existing implementation had no separation between TDM and the business logic of making calls. The whole product was hardware/technology dependent from top to bottom and could not be untangled. The whole product had essentially become firmware.

Consider another example: Command messages arrive to this system via serial port. Unsurprisingly, there is a message processor/dispatcher. The message processor knows the format of messages, is able to parse them, and can then dispatch the message to the code that can handle the request. None of this is surprising, except that the message processor/dispatcher resides in the same file as code that interacts with a UART2 hardware. The message processor is polluted with UART details. The message processor could have been software with a potentially long useful life, but instead it is firmware. The message processor is denied the opportunity to become software—and that is just not right!

I’ve known and understood the need for separating software from hardware for a long time, but Doug’s words clarified how to use the terms software and firmware in relationship to each other.

For engineers and programmers, the message is clear: Stop writing so much firmware and give your code a chance at a long useful life. Of course, demanding it won’t make it so. Let’s look at how we can keep embedded software architecture clean to give the software a fighting chance of having a long and useful life.

APP-TITUDE TEST

Why does so much potential embedded software become firmware? It seems that most of the emphasis is on getting the embedded code to work, and not so much emphasis is placed on structuring it for a long useful life. Kent Beck describes three activities in building software (the quoted text is Kent’s words and the italics are my commentary):

1. “First make it work.” You are out of business if it doesn’t work.

2. “Then make it right.” Refactor the code so that you and others can understand it and evolve it as needs change or are better understood.

3. “Then make it fast.” Refactor the code for “needed” performance.

Much of the embedded systems software that I see in the wild seems to have been written with “Make it work” in mind—and perhaps also with an obsession for the “Make it fast” goal, achieved by adding micro-optimizations at every opportunity. In The Mythical Man-Month, Fred Brooks suggests we “plan to throw one away.” Kent and Fred are giving virtually the same advice: Learn what works, then make a better solution.

Embedded software is not special when it comes to these problems. Most non-embedded apps are built just to work, with little regard to making the code right for a long useful life.

Getting an app to work is what I call the App-titude test for a programmer. Programmers, embedded or not, who just concern themselves with getting their app to work are doing their products and employers a disservice. There is much more to programming than just getting an app to work.

As an example of code produced while passing the App-titude test, check out these functions located in one file of a small embedded system:

ISR(TIMER1_vect) { ... }

ISR(INT2_vect) { ... }

void btn_Handler(void) { ... }

float calc_RPM(void) { ... }

static char Read_RawData(void) { ... }

void Do_Average(void) { ... }

void Get_Next_Measurement(void) { ... }

void Zero_Sensor_1(void) { ... }

void Zero_Sensor_2(void) { ... }

void Dev_Control(char Activation) { ... }

char Load_FLASH_Setup(void) { ... }

void Save_FLASH_Setup(void) { ... }

void Store_DataSet(void) { ... }

float bytes2float(char bytes[4]) { ... }

void Recall_DataSet(void) { ... }

void Sensor_init(void) { ... }

void uC_Sleep(void) { ... }

That list of functions is in the order I found them in the source file. Now I’ll separate them and group them by concern:

• Functions that have domain logic

float calc_RPM(void) { ... }

void Do_Average(void) { ... }

void Get_Next_Measurement(void) { ... }

void Zero_Sensor_1(void) { ... }

void Zero_Sensor_2(void) { ... }

• Functions that set up the hardware platform

ISR(TIMER1_vect) { ... }*

ISR(INT2_vect) { ... }

void uC_Sleep(void) { ... }

Functions that react to the on off button press

void btn_Handler(void) { ... }

void Dev_Control(char Activation) { ... }

A Function that can get A/D input readings from the hardware

static char Read_RawData(void) { ... }

• Functions that store values to the persistent storage

char Load_FLASH_Setup(void) { ... }

void Save_FLASH_Setup(void) { ... }

void Store_DataSet(void) { ... }

float bytes2float(char bytes[4]) { ... }

void Recall_DataSet(void) { ... }

• Function that does not do what its name implies

void Sensor_init(void) { ... }

Looking at some of the other files in this application, I found many impediments to understanding the code. I also found a file structure that implied that the only way to test any of this code is in the embedded target. Virtually every bit of this code knows it is in a special microprocessor architecture, using “extended” C constructs3 that tie the code to a particular tool chain and microprocessor. There is no way for this code to have a long useful life unless the product never needs to be moved to a different hardware environment.

This application works: The engineer passed the App-titude test. But the application can’t be said to have a clean embedded architecture.

THE TARGET-HARDWARE BOTTLENECK

There are many special concerns that embedded developers have to deal with that non-embedded developers do not—for example, limited memory space, real-time constraints and deadlines, limited IO, unconventional user interfaces, and sensors and connections to the real world. Most of the time the hardware is concurrently developed with the software and firmware. As an engineer developing code for this kind of system, you may have no place to run the code. If that’s not bad enough, once you get the hardware, it is likely that the hardware will have its own defects, making software development progress even slower than usual.

Yes, embedded is special. Embedded engineers are special. But embedded development is not so special that the principles in this book are not applicable to embedded systems.

One of the special embedded problems is the target-hardware bottleneck. When embedded code is structured without applying clean architecture principles and practices, you will often face the scenario in which you can test your code only on the target. If the target is the only place where testing is possible, the target-hardware bottleneck will slow you down.

A CLEAN EMBEDDED ARCHITECTURE IS A TESTABLE EMBEDDED ARCHITECTURE

Let’s see how to apply some of the architectural principles to embedded software and firmware to help you eliminate the target-hardware bottleneck.

Layers

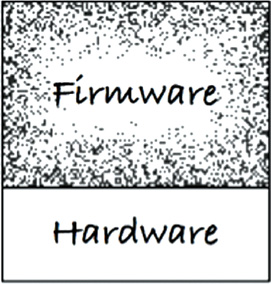

Layering comes in many flavors. Let’s start with three layers, as shown in Figure 29.1. At the bottom, there is the hardware. As Doug warns us, due to technology advances and Moore’s law, the hardware will change. Parts become obsolete, and new parts use less power or provide better performance or are cheaper. Whatever the reason, as an embedded engineer, I don’t want to have a bigger job than is necessary when the inevitable hardware change finally happens.

The separation between hardware and the rest of the system is a given—at least once the hardware is defined (Figure 29.2). Here is where the problems often begin when you are trying to pass the App-titude test. There is nothing that keeps hardware knowledge from polluting all the code. If you are not careful about where you put things and what one module is allowed to know about another module, the code will be very hard to change. I’m not just talking about when the hardware changes, but when the user asks for a change, or when a bug needs to be fixed.

Software and firmware intermingling is an anti-pattern. Code exhibiting this anti-pattern will resist changes. In addition, changes will be dangerous, often leading to unintended consequences. Full regression tests of the whole system will be needed for minor changes. If you have not created externally instrumented tests, expect to get bored with manual tests—and then you can expect new bug reports.

The Hardware Is a Detail

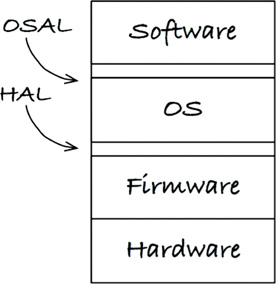

The line between software and firmware is typically not so well defined as the line between code and hardware, as shown in Figure 29.3.

Figure 29.3 The line between software and firmware is a bit fuzzier than the line between code and hardware

One of your jobs as an embedded software developer is to firm up that line. The name of the boundary between the software and the firmware is the hardware abstraction layer (HAL) (Figure 29.4). This is not a new idea: It has been in PCs since the days before Windows.

The HAL exists for the software that sits on top of it, and its API should be tailored to that software’s needs. As an example, the firmware can store bytes and arrays of bytes into flash memory. In contrast, the application needs to store and read name/value pairs to some persistence mechanism. The software should not be concerned that the name/value pairs are stored in flash memory, a spinning disk, the cloud, or core memory. The HAL provides a service, and it does not reveal to the software how it does it. The flash implementation is a detail that should be hidden from software.

As another example, an LED is tied to a GPIO bit. The firmware could provide access to the GPIO bits, where a HAL might provide Led_TurnOn(5). That is a pretty low-level hardware abstraction layer. Let’s consider raising the level of abstraction from a hardware perspective to the software/product perspective. What is the LED indicating? Suppose that it indicated low battery power. At some level, the firmware (or a board support package) could provide Led_TurnOn(5), while the HAL provides Indicate_LowBattery(). You can see the HAL expressing services needed by the application. You can also see that layers may contain layers. It is more of a repeating fractal pattern than a limited set of predefined layers. The GPIO assignments are details that should be hidden from the software.

DON’T REVEAL HARDWARE DETAILS TO THE USER OF THE HAL

A clean embedded architecture’s software is testable off the target hardware. A successful HAL provides that seam or set of substitution points that facilitate off-target testing.

The Processor Is a Detail

When your embedded application uses a specialized tool chain, it will often provide header files to <i>help you</i>.4 These compilers often take liberties with the C language, adding new keywords to access their processor features. The code will look like C, but it is no longer C.

Sometimes vendor-supplied C compilers provide what look like global variables to give access directly to processor registers, IO ports, clock timers, IO bits, interrupt controllers, and other processor functions. It is helpful to get access to these things easily, but realize that any of your code that uses these helpful facilities is no longer C. It won’t compile for another processor, or maybe even with a different compiler for the same processor.

I would hate to think that the silicon and tool provider is being cynical, tying your product to the compiler. Let’s give the provider the benefit of a doubt by assuming that it is truly trying to help. But now it’s up to you to use that help in a way that does not hurt in the future. You will have to limit which files are allowed to know about the C extensions.

Let’s look at this header file designed for the ACME family of DSPs—you know, the ones used by Wile E. Coyote:

#ifndef _ACME_STD_TYPES

#define _ACME_STD_TYPES

#if defined(_ACME_X42)

typedef unsigned int Uint_32;

typedef unsigned short Uint_16;

typedef unsigned char Uint_8;

typedef int Int_32;

typedef short Int_16;

typedef char Int_8;

#elif defined(_ACME_A42)

typedef unsigned long Uint_32;

typedef unsigned int Uint_16;

typedef unsigned char Uint_8;

typedef long Int_32;

typedef int Int_16;

typedef char Int_8;

#else

#error <acmetypes.h> is not supported for this environment

#endif

#endif

The acmetypes.h header file should not be used directly. If you do, your code gets tied to one of the ACME DSPs. You are using an ACME DSP, you say, so what is the harm? You can’t compile your code unless you include this header. If you use the header and define _ACME_X42 or _ACME_A42, your integers will be the wrong size if you try to test your code off-target. If that is not bad enough, one day you’ll want to port your application to another processor, and you will have made that task much more difficult by not choosing portability and by not limiting what files know about ACME.

Instead of using acmetypes.h, you should try to follow a more standardized path and use stdint.h. But what if the target compiler does not provide stdint.h? You can write this header file. The stdint.h you write for target builds uses the acmetypes.h for target compiles like this:

#ifndef _STDINT_H_

#define _STDINT_H_

#include <acmetypes.h>

typedef Uint_32 uint32_t;

typedef Uint_16 uint16_t;

typedef Uint_8 uint8_t;

typedef Int_32 int32_t;

typedef Int_16 int16_t;

typedef Int_8 int8_t;

#endif

Having your embedded software and firmware use stdint.h helps keep your code clean and portable. Certainly, all of the software should be processor independent, but not all of the firmware can be. This next code snippet takes advantage of special extensions to C that gives your code access to the peripherals in the micro-controller. It’s likely your product uses this micro-controller so that you can use its integrated peripherals. This function outputs a line that says "hi" to the serial output port. (This example is based on real code from the wild.)

void say_hi()

{

IE = 0b11000000;

SBUF0 = (0x68);

while(TI_0 == 0);

TI_0 = 0;

SBUF0 = (0x69);

while(TI_0 == 0);

TI_0 = 0;

SBUF0 = (0x0a);

while(TI_0 == 0);

TI_0 = 0;

SBUF0 = (0x0d);

while(TI_0 == 0);

TI_0 = 0;

IE = 0b11010000;

}

There are lots of problems with this small function. One thing that might jump out at you is the presence of 0b11000000. This binary notation is cool; can C do that? Unfortunately, no. A few other problems relate to this code directly using the custom C extensions:

IE: Interrupt enable bits.

SBUF0: Serial output buffer.

TI_0: Serial transmit buffer empty interrupt. Reading a 1 indicates the buffer is empty.

The uppercase variables actually access micro-controller built-in peripherals. If you want to control interrupts and output characters, you must use these peripherals. Yes, this is convenient—but it’s not C.

A clean embedded architecture would use these device access registers directly in very few places and confine them totally to the firmware. Anything that knows about these registers becomes firmware and is consequently bound to the silicon. Tying code to the processor will hurt you when you want to get code working before you have stable hardware. It will also hurt you when you move your embedded application to a new processor.

If you use a micro-controller like this, your firmware could isolate these low-level functions with some form of a processor abstraction layer (PAL). Firmware above the PAL could be tested off-target, making it a little less firm.

The Operating System Is a Detail

A HAL is necessary, but is it sufficient? In bare-metal embedded systems, a HAL may be all you need to keep your code from getting too addicted to the operating environment. But what about embedded systems that use a real-time operating system (RTOS) or some embedded version of Linux or Windows?

To give your embedded code a good chance at a long life, you have to treat the operating system as a detail and protect against OS dependencies.

The software accesses the services of the operating environment through the OS. The OS is a layer separating the software from firmware (Figure 29.5). Using an OS directly can cause problems. For example, what if your RTOS supplier is bought by another company and the royalties go up, or the quality goes down? What if your needs change and your RTOS does not have the capabilities that you now require? You’ll have to change lots of code. These won’t just be simple syntactical changes due to the new OS’s API, but will likely have to adapt semantically to the new OS’s different capabilities and primitives.

A clean embedded architecture isolates software from the operating system, through an operating system abstraction layer (OSAL) (Figure 29.6). In some cases, implementing this layer might be as simple as changing the name of a function. In other cases, it might involve wrapping several functions together.

If you have ever moved your software from one RTOS to another, you know it is painful. If your software depended on an OSAL instead of the OS directly, you would largely be writing a new OSAL that is compatible with the old OSAL. Which would you rather do: modify a bunch of complex existing code, or write new code to a defined interface and behavior? This is not a trick question. I choose the latter.

You might start worrying about code bloat about now. Really, though, the layer becomes the place where much of the duplication around using an OS is isolated. This duplication does not have to impose a big overhead. If you define an OSAL, you can also encourage your applications to have a common structure. You might provide message passing mechanisms, rather than having every thread handcraft its concurrency model.

The OSAL can help provide test points so that the valuable application code in the software layer can be tested off-target and off-OS. A clean embedded architecture’s software is testable off the target operating system. A successful OSAL provides that seam or set of substitution points that facilitate off-target testing.

PROGRAMMING TO INTERFACES AND SUBSTITUTABILITY

In addition to adding a HAL and potentially an OSAL inside each of the major layers (software, OS, firmware, and hardware), you can—and should—apply the principles described throughout this book. These principles encourage separation of concerns, programming to interfaces, and substitutability.

The idea of a layered architecture is built on the idea of programming to interfaces. When one module interacts with another though an interface, you can substitute one service provider for another. Many readers will have written their own small version of printf for deployment in the target. As long as the interface to your printf is the same as the standard version of printf, you can override the service one for the other.

One basic rule of thumb is to use header files as interface definitions. When you do so, however, you have to be careful about what goes in the header file. Limit header file contents to function declarations as well as the constants and struct names that are needed by the function.

Don’t clutter the interface header files with data structures, constants, and typedefs that are needed by only the implementation. It’s not just a matter of clutter: That clutter will lead to unwanted dependencies. Limit the visibility of the implementation details. Expect the implementation details to change. The fewer places where code knows the details, the fewer places where code will have to be tracked down and modified.

A clean embedded architecture is testable within the layers because modules interact through interfaces. Each interface provides that seam or substitution point that facilitates off-target testing.

DRY CONDITIONAL COMPILATION DIRECTIVES

One use of substitutability that is often overlooked relates to how embedded C and C++ programs handle different targets or operating systems. There is a tendency to use conditional compilation to turn on and off segments of code. I recall one especially problematic case where the statement #ifdef BOARD_V2 was mentioned several thousand times in a telecom application.

This repetition of code violates the Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle.5 If I see #ifdef BOARD_V2 once, it’s not really a problem. Six thousand times is an extreme problem. Conditional compilation identifying the target-hardware’s type is often repeated in embedded systems. But what else can we do?

What if there is a hardware abstraction layer? The hardware type would become a detail hidden under the HAL. If the HAL provides a set of interfaces, instead of using conditional compilation, we could use the linker or some form of runtime binding to connect the software to the hardware.

CONCLUSION

People who are developing embedded software have a lot to learn from experiences outside of embedded software. If you are an embedded developer who has picked up this book, you will find a wealth of software development wisdom in the words and ideas.

Letting all code become firmware is not good for your product’s long-term health. Being able to test only in the target hardware is not good for your product’s long-term health. A clean embedded architecture is good for your product’s long-term health.

1. https://insights.sei.cmu.edu/sei_blog/2011/08/the-growing-importance-of-sustaining-software-for-thedod.html

2. The hardware device that controls the serial port.

3. Some silicon providers add keywords to the C language to make accessing the registers and IO ports simple from C. Unfortunately, once that is done, the code is no longer C.

4. This statement intentionally uses HTML.

5. Hunt and Thomas, The Pragmatic Programmer.