8. Closures

In This Chapter

• Understand what closures are

• Tie together everything you’ve learned about functions, variables, and scope

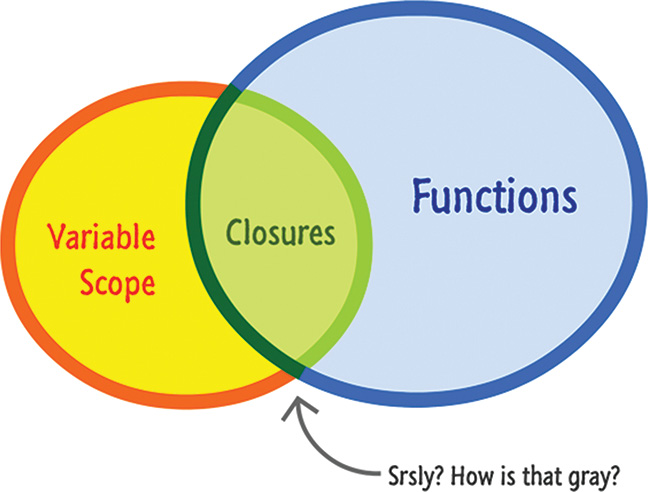

By now, you probably know all about functions and all the fun functioney things that they do. An important part of working with functions, with JavaScript, and (possibly) life in general is understanding the topic known as closures. Closures touch upon a gray area where functions and variable scope intersect (see Figure 8.1).

Now, I am not going to say any thing more about closures, as this is something best explained by seeing the actual code. Any words I add right now to define or describe closures will only serve to confuse things. In the following sections, we’ll start off in familiar territory and then slowly venture into hostile areas where closures can be found.

Onwards!

Functions within Functions

The first thing we are going to do is really drill down on what happens when you have functions within functions...and the inner function gets returned. As part of that, let’s do a quick review of functions.

Take a look at the following code:

function calculateRectangleArea(length, width) {

return length * width;

}

var roomArea = calculateRectangleArea(10, 10);

alert(roomArea);

The calculateRectangleArea function takes two arguments and returns the multiplied value of those arguments to whatever called it. In this example, the “whatever called it” part is played by the roomArea variable.

After this code has run, the roomArea variable contains the result of multiplying 10 by 10...which is simply 100. Figure 8.2 visualizes this situation:

As you know, what a function returns can pretty much be anything. In this case, we returned a number. You can very easily return some text (aka a String), the undefined value, a custom object, and so on. As long as the code that is calling the function knows what to do with what the function returns, you can do pretty much whatever you want. You can even return another function. Let me rathole on this a bit.

Below is a very simple example of what I am talking about:

function youSayGoodbye() {

alert("Goodbye!");

function andISayHello() {

alert("Hello!");

}

return andISayHello;

}

You can have functions that contain functions inside them. In this example, we have our youSayGoodbye function that contains an alert and another function called andISayHello:

The interesting part is what the youSayGoodbye function returns when it gets called. It returns the andISayHello function:

alert("Goodbye!");

function andISayHello() {

alert("Hello!");

}

}

Let’s go ahead and play this example out. To call this function, initialize a variable that points to youSayGoodbye:

var something = youSayGoodbye();

The moment this line of code runs, all of the code inside your youSayGoodbye function will get run as well. This means, you will see a dialog box (thanks to the alert) that says Good Bye! The andISayHello function gets returned. The important thing to note is that the andISayHello function does not get run yet, for we haven’t actually called it. We simply return a reference to it.

At this point, your something variable only has eyes for one thing, and that thing is the andISayHello function:

The youSayGoodbye outer function, from the something variable’s point of view, simply goes away. Because the something variable now points to a function, you can invoke this function by just calling it using the open and close parentheses like you normally would:

var something = youSayGoodbye();

something();

When you do this, the returned inner function (aka andISayHello) will execute. Just like before, you will see a dialog box appear, but this dialog box will say Hello!—which is what the alert inside this function specified.

Okay, we are getting close to the promised hostile territory. In the next section, we will expand on what we’ve just learnt by taking a look at another example with a slight twist.

When the Inner Functions Aren’t Self-Contained

In the previous example, your andISayHello inner function was self-contained and didn’t rely on any variables from the outer function:

alert("Goodbye!");

alert("Hello!");

}

return andISayHello;

}

In many real scenarios, very rarely will you run into a case like this. You’ll often have variables and data that is shared between the outer function and the inner function. To highlight this, take a look at the following:

function stopWatch() {

var startTime = Date.now();

function getDelay() {

var elapsedTime = Date.now() - startTime;

alert(elapsedTime);

}

return getDelay;

}

This example shows a very simple way of measuring the time it takes to do something. Inside the stopWatch function, you have a startTime variable that is set to the value of Date.now():

function getDelay() {

var elapsedTime = Date.now() - startTime;

alert(elapsedTime);

}

return getDelay;

}

The Date.now() function is something we haven’t seen before, so let’s quickly take a look at it. What this function does is return a really large number that represents the current time. More specifically, the really large number is the number of milliseconds that have elapsed since 1 January 1970 00:00:00 UTC.

You also have an inner function called getDelay:

var startTime = Date.now();

var elapsedTime = Date.now() - startTime;

alert(elapsedTime);

}

return getDelay;

}

The getDelay function displays a dialog box containing the difference in time between a new call to Date.now() and the startTime variable declared earlier.

Getting back to the outer stopWatch function, the last thing that happens is that it returns the getDelay function before exiting. As you can see, the code you see here is very similar to the earlier example. You have an outer function, you have an inner function, and you have the outer function returning the inner function.

Now, to see the stopWatch function at work, add the following lines of code:

var timer = stopWatch();

// do something that takes some time

for (var i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

var foo = Math.random() * 10000;

}

// call the returned function

timer();

If you run this example, you’ll see a dialog box displaying the number of milliseconds it took between your timer variable getting initialized, your for loop running to completion, and the timer variable getting invoked as a function. Basically, you have a stopwatch that you invoke, run some long-running operation, and invoke again to see how long the long-running operation took place.

Now that you can see our little stopwatch example working, let’s go back to the stopWatch function and see what exactly is going on. Like I mentioned a few lines ago, a lot of what you see is similar to the youSayGoodbye/andISayHello example. There is a twist that makes this example different, and the important part to note is what happens when the getDelay function is returned to the timer variable.

Here is an incomplete visualization of what this looks like:

The stopWatch outer function is no longer in play, and the timer variable is still tied to the getDelay function. Now, here is the twist. The getDelay function relies on the startTime variable that lives in the scope of the outer stopWatch function:

function getDelay() {

alert(elapsedTime);

}

return getDelay;

}

When the outer stopWatch function runs and disappears once getDelay is returned to the timer variable, what happens in the following line?

alert(elapsedTime);

}

In this context, it would make sense if the startTime variable is actually undefined, right? But, the example obviously worked, so something else is going on here. That something else is the shy and mysterious closure. Here is a look at what happens to make our startTime variable actually store a value and not be undefined.

The JavaScript runtime that keeps track of all of your variables, memory usage, references, and so on is really clever. In this example, it detects that the inner function (getDelay) is relying on variables from the outer function (stopWatch). When that happens, the runtime ensures that any variables in the outer function that are needed are still available to the inner function even if the outer function goes away.

To visualize this properly, here is what the timer variable looks like:

It is still referring to the getDelay function, but the getDelay function also has access to the startTime variable that existed in the outer stopWatch function. This inner function, because it enclosed relevant variables from the outer function into its bubble (aka scope), is known as a closure:

To define the closure more formally, it is a newly created function that also contains its variable context:

To review this one more time using our existing example, the startTime variable gets the value of Date.now the moment the timer variable gets initialized and the stopWatch function runs. When the stopWatch function returns the inner getDelay function, the stopWatch function is no longer active. You can sort of say that it goes away. What doesn’t go away are any shared variables inside stopWatch that the inner function relies on. Those shared variables are not destroyed. Instead, they are enclosed by the inner function aka the closure.

Just a quick reminder for those of you reading these words in the print or e-book edition of this book: If you go to www.quepublishing.com and register this book, you can receive free access to an online Web Edition that not only contains the complete text of this book but also features a short, fun interactive quiz to test your understanding of the chapter you just read.

If you’re reading these words in the Web Edition already and want to try your hand at the quiz, then you’re in luck – all you need to do is scroll down!