1

Introducing React

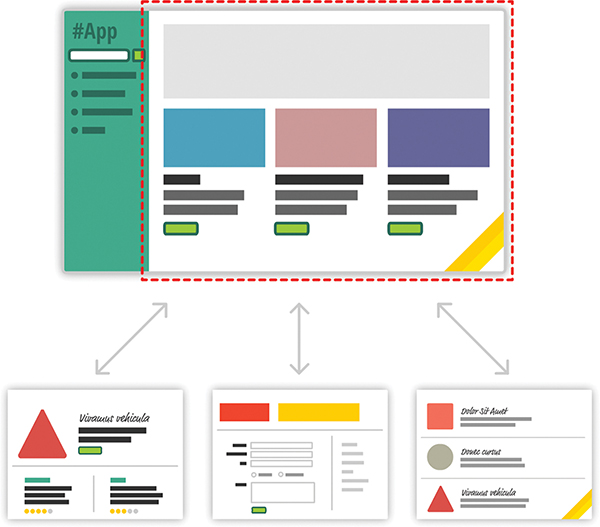

Ignoring for a moment that web apps today both look and feel nicer than they did back in the day, something even more fundamental has changed. The way we architect and build web apps is very different now. To highlight this, let’s take a look at the app in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 An app.

This app is a simple catalog browser for something. As with any app of this sort, you have your usual set of pages revolving around a home page, a search results page, a details page, and so on. In the following sections, let’s look at the two approaches we have for building this app. Yes, in some mysterious fashion, this leads to us getting an overview of React as well.

Onward!

Old-School Multipage Design

If you had to build this app a few years ago, you might have taken an approach that involved multiple, individual pages. The flow would have looked something like Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Multipage design.

For almost every action that changes what the browser displays, the web app navigates you to a whole different page. This is a big deal, beyond just the less-than-stellar user experience users will see as pages get torn down and redrawn. This has a big impact on how you maintain your app state. Except for storing user data via cookies and some server-side mechanism, you simply don’t need to care. Life is good.

New-School Single-Page Apps

These days, going with a web app model that requires navigating between individual pages seems dated—really dated. Check out Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 The individual page model is a bit dated, like this steam engine.

Instead, modern apps tend to adhere to what is known as a single-page app (SPA) model. This model gives you a world in which you never navigate to different pages or ever even reload a page. In this world, the different views of your app are loaded and unloaded into the same page itself.

For our app, this looks something like Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4 Single-page app.

As users interact with our app, we replace the contents of the dotted red region with the data and HTML that matches what the user is trying to do. The end result is a much more fluid experience. You can even use a lot of visual techniques to have your new content transition nicely, just like you might see in cool apps on your mobile device or desktop. This sort of stuff is simply not possible when navigating to different pages.

All of this might sound a bit crazy if you’ve never heard of single-page apps, but there’s a very good chance you’ve run into some of them in the wild. If you’ve ever used popular web apps like Gmail, Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter, you’ve used a single-page app. In all those apps, the content gets dynamically displayed without requiring you to refresh or navigate to a different page.

Now, I’m making these single-page apps seem really complicated. That’s not entirely the case. Thanks to a lot of great improvements in both JavaScript and a variety of third-party frameworks and libraries, building single-page apps has never been easier. That doesn’t mean there’s no room for improvement, though.

When building single-page apps, you’ll encounter three major issues at some point:

1. In a single-page application, you’ll spend the bulk of your time keeping your data in sync with your UI. For example, if a user loads new content, do you explicitly clear out the search field? Do you keep the active tab on a navigation element still visible? Which elements do you keep on the page, and which do you destroy?

These are all problems that are unique to single-page apps. When navigating between pages in the old model, we assumed everything in our UI would be destroyed and just built back up again. This was never a problem.

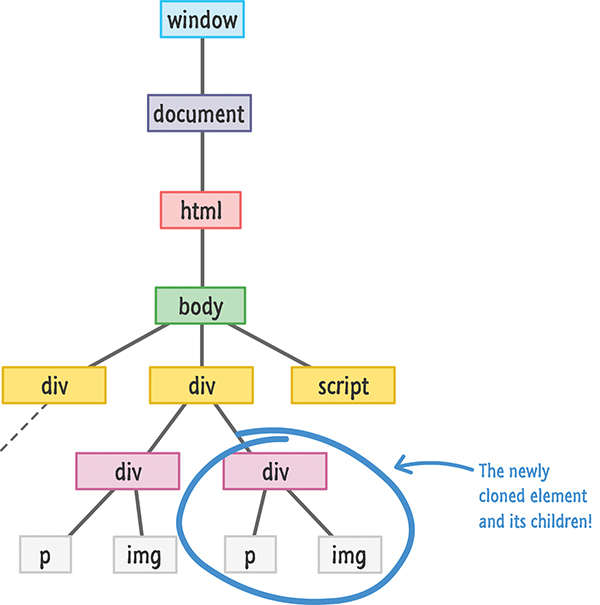

2. Manipulating the DOM is really, really slow. Manually querying elements, adding children (see Figure 1.5), removing subtrees, and performing other DOM operations is one of the slowest things you can do in your browser. Unfortunately, in a single-page app, you’ll be doing a lot of this. Manipulating the DOM is the primary way you are able to react to user actions and display new content.

Figure 1.5 Adding children.

3. Working with HTML templates can be a pain. Navigation in a single-page app is nothing more than you dealing with fragments of HTML to represent whatever you want to display. These fragments of HTML are often known as templates, and using JavaScript to manipulate them and fill them out with data gets really complicated really quickly.

To make things worse, depending on the framework you’re using, the way your templates look and interact with data can vary wildly. For example, this is what defining and using a template in Mustache looks like:

var view = { title: "Joe", calc: function() { return 2 + 4; } }; var output = Mustache.render("{{title}} spends {{calc}}", view);

Sometimes your templates look like clean HTML that you can proudly show off in front of the class. Other times, your templates might be unintelligible, with a boatload of custom tags designed to help map your HTML elements to some data.

Despite these shortcomings, single-page apps aren’t going anywhere. They are a part of the present and will fully form the future of how web apps are built. That doesn’t mean you have to tolerate these shortcomings, of course. Read on.

Meet React

Facebook (and Instagram) decided that enough is enough. Given their huge experience with single-page apps, they released a library called React to not only address these shortcomings, but also change how we think about building single-page apps.

In the following sections, we look at the big things React brings to the table.

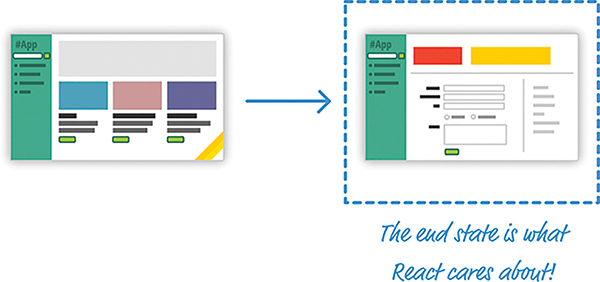

Automatic UI State Management

With single-page apps, keeping track of your UI and maintaining state is hard … and also very time consuming. With React, you need to worry about only one thing: the final state of your UI. It doesn’t matter what state your UI started out in. It doesn’t matter what series of steps your users took to change the UI. All that matters is where your UI ended up (see Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6 The final or end state of your UI is what matters in React.

React takes care of everything else. It figures out what needs to happen to ensure that your UI is represented properly so that all that state-management stuff is no longer your concern.

Lightning-Fast DOM Manipulation

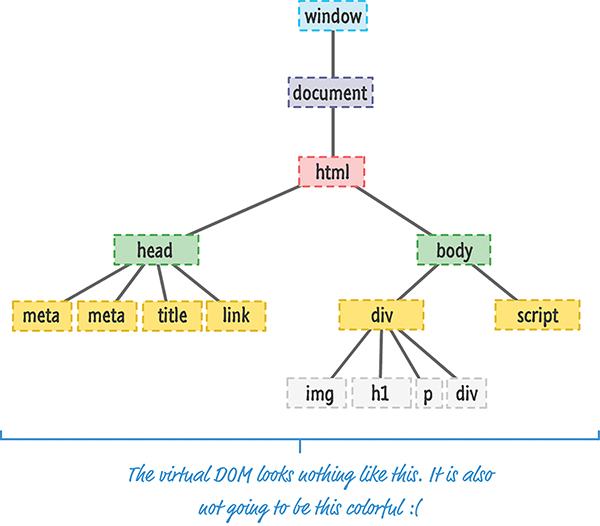

Because DOM modifications are really slow, you never modify the DOM directly using React. Instead, you modify an in-memory virtual DOM (resembling what you see in Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7 Imagine an in-memory virtual DOM that sort of looks like this.

Manipulating this virtual DOM is extremely fast, and React takes care of updating the real DOM when the time is right. It does so by comparing the changes between your virtual DOM and the real DOM, figuring out which changes actually matter, and making the fewest number of DOM changes needed to keep everything up-to-date in a process called reconciliation.

APIs to Create Truly Composable UIs

Instead of treating the visual elements in your app as one monolithic chunk, React encourages you to break your visual elements into smaller and smaller components (see Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8 An example of how the visuals of your app can be broken into smaller pieces.

As with everything else in programming, it’s a good idea to make things modular, compact, and self-contained. React extends that well-worn idea to how we think about user interfaces. Many of React’s core APIs revolve around making it easier to create smaller visual components that can later be composed with other visual components to make larger and more complex visual components—kind of like the Russian matryoshka dolls in Figure 1.9. (see Figure 1.8):

Figure 1.9 Russian matryoshka dolls.

This is one of the major ways React simplifies (and changes) how we think about building the visuals for our web apps.

Visuals Defined Entirely in JavaScript

While this sounds ridiculously crazy and outrageous, hear me out. Besides having a really weird syntax, HTML templates have traditionally suffered from another major problem: You are limited in the variety of things you can do inside them, which goes beyond simply displaying data. If you want to choose a piece of UI to display based on a particular condition, for example, you have to write JavaScript somewhere else in your app or use some weird framework-specific templating command to make it work.

For example, here’s what a conditional statement inside an EmberJS template looks like:

Welcome back, {{person.firstName}} {{person.lastName}}!

{{else}}

Please log in.

{{/if}}

React does something pretty neat. By having your UI defined entirely in JavaScript, you get to use all the rich functionality JavaScript provides for doing all sorts of things inside your templates. You are limited only by what JavaScript supports, not limitations imposed by your templating framework.

Now, when you think of visuals defined entirely in JavaScript, you’re probably thinking something horrible that involves quotation marks, escape characters, and a whole lot of createElement calls. Don’t worry. React allows you to (optionally) specify your visuals using an HTML-like syntax known as JSX that lives fully alongside your JavaScript. Instead of writing code to define your UI, you are basically specifying markup:

<h1>Batman</h1>

<h1>Iron Man</h1>

<h1>Nicolas Cage</h1>

<h1>Mega Man</h1>

</div>,

destination

This same code defined in JavaScript would look like this:

"div",

null,

React.createElement(

"h1",

null,

"Batman"

),

React.createElement(

"h1",

null,

"Iron Man"

),

React.createElement(

"h1",

null,

"Nicolas Cage"

),

React.createElement(

"h1",

null,

"Mega Man"

)

), destination);

Yikes! Using JSX, you are able to easily define your visuals using a very familiar syntax, while still getting all the power and flexibility that JavaScript provides.

Best of all, in React, your visuals and JavaScript often live in the same location. You no longer have to jump among multiple files to define the look and behavior of one visual component. This is templating done right.

Just the V in an MVC Architecture

We’re almost done here! React is not a full-fledged framework that has an opinion on how everything in your app should behave. Instead, React works primarily in the View layer, where all of its worries and concerns revolve around keeping your visual elements up-to-date. This means you’re free to use whatever you want for the M and C parts of your MVC (a.k.a. Model-View-Controller) architecture. This flexibility allows you to pick and choose technologies you are familiar with, and it makes React useful not only for new web apps you create, but also for existing apps you’d like to enhance without removing and refactoring a whole bunch of code.

Conclusion

As new web frameworks and libraries go, React is a runaway success. It not only deals with the most common problems developers face when building single-page apps, but it also throws in a few additional tricks that make building the visuals for your single-page apps much easier. Since it came out in 2013, React has also steadily found its way into popular web sites and apps that you probably use. Besides Facebook and Instagram, some notable ones include the BBC, Khan Academy, PayPal, Reddit, The New York Times, and Yahoo!, among many others.

This article was an introduction to what React does and why it does it. In subsequent chapters, we’ll dive deeper into everything you’ve seen here and cover the technical details that will help you successfully use React in your own projects. Stick around.