CHAPTER 8

THE WRITING PROCESS

Authorship starts with the writer at a keyboard, develops through the director's process of mise en scène (design for directing), and reaches its apotheosis under the hand of the editor during postproduction. Already there are three people involved with a professional production, and we could add the DP, art director, actors, and many others to the authorial process.

Screenwriting, once a discrete craft, is now commonly included in a larger authorial process that the director often shares and influences. Some cinema directors write their own material, but the majority work closely with writers. Whether a script is generated by a director, alone or in partnership with a writer, its attributes will largely determine the movie. A good script is the visionary blueprint that unites everyone involved in realizing the film.

PITCHING

Whether you are a writer beginning a script or a director or producer with a finished property (script they have paid for) looking for finance, you will constantly have to “sell” a current project. Called pitching a project, the word comes from baseball and means projecting the essentials of a screen story rapidly and attractively. You may get 10 minutes to convey a feature screenplay in professional situations, and 20 minutes maximum for a pitch to studio executives. You should be able to pitch a short film in 3–5 minutes.

Pitching is neither easy nor comfortable, but under any circumstances it is an excellent exercise. There is no set formula, and part of the challenge is to handle the idea in the way that best suits it. The most important quality to convey is your passion and belief in the special qualities of the story. Here's what you might cover for a short film:

- Title and brief overview (Example: “This story is called Deliverance and is about four urban businessmen celebrating freedom by canoeing through unspoiled Appalachia. When they find they are the prey of degenerate, vengeful mountain men, each must put notions of manhood to the test as they struggle against the odds to survive.”)

- Genre

- Main character and the problems that he or she faces in life generally

- Main character's problem or predicament

- Obstacles main character must overcome

- Why these obstacles matter, what is at stake, and why an audience should give a damn

- Changes the main character undergoes

- Resolution: how he or she is at the end

- Cinematic qualities that make the film very special

Pitch over and over again to anyone who will listen to you until you are fluent. From each new listener's face, attitude, and body language, you will be able to tell whether your idea grips them and where it fails. If it's not working, change whatever is wrong until you get it right. These are your first audiences, and you know you have a good idea once listeners are excited and spontaneously enthusiastic.

There are innumerable screenwriting Web sites, but here are two that deal with pitching to studio executives: breakingin.net/tswpitching.htm and www.sydfield.com/artofpitching.htm.

The more you read, the more you understand how vital pitching is and how irregular it is in practice.

Go to screenwriting workshops and especially festivals that feature pitching sessions, and trawl the Internet for screenwriting competitions. If you fancy yourself a writer, win recognition for it. Filmmakers Magazine has an annual contest (see www.filmmakers.com/contests/short/2002/) and the rules are fairly typical. Read every contest's rules very carefully, and if you sign a legal release, be absolutely sure you understand all the implications because you may be giving away your baby. The entry fee for screenwriting contests is usually $18–$50, and you usually win a cash prize or have the script submitted for professional consideration. Rules usually specify that you are over 18, have not adapted the idea, write in English or another given language, and that your opus is of a specified length. It is absolutely vital that you write in standard screenplay form, following the specs for format, binding, and cover minutely and to the last brass staple. Always check to be sure you can make the deadline: Old Internet postings never die, and you could be entering something that's already history.

The Screenwriter's Forum (www.screenwritersforum.com/) is one Web site with a contest, but you can find many of them by using Google or other search engines and the keywords “screenwriting contest” or “screenwriting.” Another supportive organization for screenwriters is Cinestory (www.cinestory.com/), and it, too, has contests, as well as events and online information to aid and encourage the new writer. More is written about writing for the screen than any other aspect of filmmaking, so screenwriters have many resources.

WHY NOT WRITE ALL YOUR OWN SCREENPLAYS?

You may be thinking, “For a student, can there really be an argument for using someone else's screenplay?” The short answer is no, not for your first films. While you scramble to learn the basics you won't have time to wait for someone else to write them. Besides, at entry level it's important to have hands-on experience with all the creative cérafts, writing included. Quite soon, though, the pace slows and the stakes become higher. Nobody will tell you that writing isn't your strong point, and it's easy to hide from that fact. Ambitious directors shoot themselves in the foot by using only their own writing. Particularly when your directorial learning curve is steepest, you need all your concentration and more for that most difficult and complex craft in filmmaking—directing. Find a strong script that you really like and direct it.

Why is there such an aversion to this? Seemingly the auteur mythology about filmmaking elevates the integrity and control of one person's vision, and leads many to assume that directing is not legitimate unless you both write and direct. Major film schools around the world have realized that this fails to produce the best films from their student population, and worse, sends students out into the world ill-equipped to function. Many schools are instituting a different nexus for project inception. At the very least they are making conditions more favorable to group productions with separate people in writing, producing, directing, and editing roles.

However, many students resist this out of cultural assumptions about being an artist and insist on writing and directing all their own work. They gamble everything, and if they don't win recognition, throw in the sponge. Afterwards nobody can say whether or not a perfectly viable screenwriter, director, or editor might have developed, had the person not tried to wear all three hats. Who in their right mind would try to learn juggling with knives while also learning to ride a unicycle across a high wire? Some skills must be mastered separately before trying to combine them.

The auteur notion of filmmaking was a useful antidote to industrial filmmaking in the 1950s and ′60s but was never a working reality. Fiction films have always been made by creative teams that get behind a script or improvisational scripting process. I am only exaggerating a little if I liken directors to sailing ship figureheads: out front and highly visible, of great symbolism, but wholly dependent on who and what propels them. As a director you have so much to control that you depend on the creative input of others. Directing means giving control of their parts to actors, of the camera to a camera operator, lighting to a DP, sound recording to a recordist, the editing to an editor … and writing to a writer. As a director you coordinate the work of all these people, and you work through them. You need their skills and you need their values. Their separate judgments help you attain some distance on the material so you can retain a sense of how it must strike a first-time audience.

THE RISE OF THE ENTREPRENEURIAL PRODUCER

Another contemporary movement in world film schools, as in my own, is to make entrepreneurial producing a major element in film school education. My college has a thriving undergraduate producing program that includes residential study and internship in Hollywood (see the Semester in LA program via www.filmatcolumbia.com). Producers are needed in low-budget filmmaking not only to manage money or do the public relations legwork, but to shop for promising scripts, develop creative teams around them, and work at the business model that will make them viable. This means working at the fundraising, co-funding, and pre-sales that today make professional filmmaking possible.

To the auteur student, the producer has figured no higher than a production manager. Now the producer is becoming a leading entrepreneurial figure who specializes in the business (yes, it's a business) of getting projects afloat and who is not a frustrated director or a frustrated anything else. There is wide support for this cultural shift. The Brussels-based international association of film schools CILECT (Centre International de Liaison des Écoles de Cinéma et de Télévision—see www.cilect.org) initiated the Triangle Project expressly to investigate the entrepreneurial partnerships that lie behind many successful European films. Like so many independent films, they cannot draw upon Hollywood financing. CILECT'S favored model is a three-person team of producer, screenwriter, and director. The Triangle idea (as it's called) is to cultivate collaborative project teams that have several projects afloat at any time, rather than the traditional approach, which is to bet the bank on a single horse.

DAMMIT, I WANT TO BE A HYPHENATION

Are you still determined to become a writer-director (or hyphenation)? Why not make it a goal for 10 or 20 years into your career? For now, as you try to improve on the basics in film school or as an independent, you really should shop for a writer just as you seek all your other collaborators. If you want to develop as a writer, why not write material for your best friend to direct?

Still not convinced? Consider this: Most people's early writing uses autobiographical sources, naturally enough. Without some distance from your work, you will find yourself trying to reanimate remembered situations and expecting your actors to reproduce something only you can know about. The mere presence of a writer as a collaborator will help displace the original where it belongs: as drama running under its own fictional imperatives. You need confidence when you direct. If the script is a vital part of your life, anyone who queries it will seem to challenge your plausibility as a person. Do you want to risk annihilating your self-esteem and negating your authority as a director?

The screen's overwhelming strength, success, and relevance, since its inception, has come from the process's division of labor. This is an additive process of creation, where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. The process tempers each contribution with checks and balances that are vital to an audience medium.

THE DOGME GROUP AND CREATIVE LIMITATION

In 1995, the founding members of the Danish Dogme 95 Cinema Group (Figure 8.1) were Thomas Vinterberg, Lars von Trier, Christian Levring, and Søren

Kragh-Jacobsen. In the next few years, the group members produced such extraordinary films as Breaking the Waves (Lars von Trier, 1999), The Celebration (Thomas Vinterberg, 1998), and The Idiots (Lars von Trier, 1999). They began by playfully setting up rules of limitation, rather as the photographers Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Ansel Adams, and Willard Van Dyke had done in 1932 for their group, f/64. The photographers—tired of pictorial work in which photography tried to make itself look more like painting, charcoal sketches, or etching—proclaimed that photography would only be liberated to become itself by rejecting everything borrowed from other pictorial forms, so they concentrated on developing photography's own attributes.

Compare this with the Dogme Group's “Vow of Chastity,” which appears in various versions and translations. I have taken minor editorial liberties to render it into vernacular English:

- Shooting must be done on location. Props and sets must not be brought in, but shooting must go where that set or prop can be found.

- Sound must never be produced separately from the images or vice versa. Music must not be used unless it occurs where the scene is shot.

- The camera must be handheld. Any movement or immobility attainable by handholding is permitted. The action cannot be organized for the camera; instead the camera must go to the action.

- The film must be in color. Special lighting is not acceptable, and if there is too little light for exposure, the scene must be cut or a single lamp may be attached to the camera.

- Camera filters and other optical work are forbidden.

- The film must not contain any superficial action such as murders, weapons, explosions, and so on.

- No displacement is permitted in time or space: The film takes place here and now.

- Genre movies are not acceptable.

- Film format is Academy 35mm.

- The director must not be credited. Furthermore, I swear as a director to refrain from personal taste. I am no longer an artist. I swear to refrain from creating a “work,” as I regard the instant as more important than the whole. My supreme goal is to force the truth out of my characters and settings. I swear to do so by all the means available and at the cost of any good taste and any aesthetic considerations.

Signed _____________

The last clause is interesting because it forswears a leadership hierarchy, personal taste, and strikes a mortal blow at ego. Instead, it passes preeminence to the cast. Of course, in practice any number of contradictions will appear, but the group's work, and the high praise it called forth from actors, demands that we take the spirit of the manifesto seriously. Thomas Vinterberg, interviewed by Elif Cercel for Director's World, said:

We did the “Vow of Chastity” in half an hour, and we had great fun. Yet, at the same time, we felt that in order to avoid the mediocrity of filmmaking not only in the whole community, but in our own filmmaking as well, we had to do something different. We wanted to undress film, turn it back to where it came from and remove the layers of makeup between the audience and the actors. We felt it was a good idea to concentrate on the moment, on the actors and, of course, on the story that they were acting, which are the only aspects left when everything else is stripped away. Also, artistically it has created a very good place for us to be as artists or filmmakers because having obstacles like these means you have something to play against. It encourages you to actually focus on other approaches instead. (stage.directorsworld.com)

Following this vow put Danish film at the forefront of international cinema and induced the Danish government to increase State funding by 70% over the next 4 years. The moral? All undertakings profit from creatively inspired limitations. Some are inbuilt, some encountered, and the best are chosen to squeeze your inventiveness. The Dogme Group's rules de-escalated the importance of filming in favor of working with actors and handed their excellent actors a rich slice of creative control. The actors responded handsomely.

So, what creative limitations will you set yourself?

WHAT SCREENWRITING IS

When writing a screenplay, you try to put on paper the movie you see in your mind. You can only set down what can be put in words, and words can describe only a portion of cinema's capabilities. Even then, something effective in writing may not translate into effective cinema. How, for instance, could you ever film “By the light of a melancholy sunset she broods upon the children she will never have”?

Screenwriting needs to be guided by knowledge of film, both as a medium and as a production process. A screenplay is a blueprint, not a complete form of expression. It will be turned into a polished, professional movie by many specialized and idiosyncratic minds working together—actors as well as camera, sound, art direction, props, and so on. Dialogue that a writer may imagine has a set meaning can, in the mouth of an accomplished actor, acquire an unforeseen range of shading and subtlety. These nuances, even if you happen to think of them, are impossible to specify in a screenplay.

Open the screenplay to criticism early and often. You and your partner cannot please everybody, but you can listen, and you can recognize real problems early, particularly when several critics are saying the same thing. This is learning from an early audience, much as a playwright will evolve a new play in the light of audience reactions. For once a movie is completed, it becomes a fly set in amber. To survive and prosper, you must submit drafts of your work to representative readers or audiences, seek out its weaknesses, and attend to them while you can. Regrettably, this is the least practiced of necessary arts among film students, who walk in mortal terror of an idea being stolen. This is not completely unrealistic, but the dangers are very much exaggerated and should never inhibit you from profiting from intensive discussions. Reinvigorated cinema, like any art form, always seems to come from a group's profound exploration of fundamentals, a discourse that no individual would have the time, energy, or inventiveness to sustain alone.

WRITING A SCREENPLAY

Writing is a major part of the creative process in fiction filmmaking, and results are deeply affected by how you set about it. Anyone at all serious about directing should be writing all the time, for the act of writing is really the mind contemplating its own workings—and thus willfully transcending its own preliminary ideas and decisions. People who don't write and rewrite are people who don't care to think in depth.

To write you must learn touch typing. It takes 10 or 15 hours of lessons, and if I learned it, believe me, anyone can. With computers making writing (and particularly rewriting) so much faster, touch typing is absolutely the most useful skill you will ever acquire. A word processor gives you easy changes, a thesaurus, and spelling checks to catch typing errors. It also gives you the capacity to make an outline and collapse it down to essentials or expand it with different levels of detail.

Set aside regular periods of time and make yourself write, no matter whether the results are good or bad. The first draft is the hardest, so do not wait to feel inspired, just keep hacking away. Write scenes that interest you, and write fast rather than writing well or in scene order. Get it down any old way. Once a few things are down, you can edit, develop, and connect what you have written.

It is very important to always write as if for the silent screen. Writing for the camera, rather than thinking in conversational exchanges, means dealing with human and other exteriors. To make your characters' inner lives accessible, keep in mind that a person has no inner experience without outward signs in his or her behavior. Keep writing until you find them. If this or any other advice stops you from writing, then write early drafts any way you can. Write any way, anywhere, anyhow—just write, rewrite, and rewrite again.

IDEA CLUSTERING, NOT LINEAR DEVELOPMENT

Most people who want to write but cannot are suffering the damage of doctrinaire teaching. The most common block results from trying to write from an outline in a linear fashion—beginning, middle, and end. At some point the writer ends up in a desert with nowhere to go. Perfectionism, which is the fear of your own judgment and that of others, is another virulent paralyzer. Remember, most unhappiness comes from comparison. Perfectionism is fine in its place—polishing your crafted product to its ultimate form—but when applied to early work it's a killer. Most writing manuals are very prescriptive and will actually stop you from writing.

At any stage, when you hit the brick wall, you can always resort to your associative ability. Where the pedestrian intellect fails, the exuberant subconscious will obligingly run rings around it. Here is a way to turn it loose:

- Take a large sheet of paper and write whatever central idea you are dealing with in the middle. It might be “happiness” or “rebuilding the relationship.”

- Now, as fast as you can write, surround it with associated words, no matter how far removed or wacky. The circle of words should look like satellites around a planet.

- Around each associated word, put another ring of words you associate with it. Soon your paper will be crammed with a little solar system.

- Now examine what you have written and turn it into a list that structures the ideas into a progression of families, groups, and systems—anything that speaks of relationship.

- While engaged in this busywork all kinds of solutions to your original problem will take shape.

WRITING IS CIRCULAR, NOT LINEAR

Finished writing is linear, but the process of getting there is anything but. Scripts are not written in the order of concept, step outline, and screenplay, nor as beginning, middle, and end. Although the odd screenwriter may work this way, he or she is just as likely to write the most clearly visualized scenes first, making an outline to gain an overview, and finally filling in the gaps and distilling the concept from the results.

Like any art process, scriptwriting—indeed filmmaking itself—looks untidy and wastefully circular to the uninitiated, and quite alien to the tidy manufacturing processes dear to the commercial mind (your producer, perhaps). This produces much friction and misery in the film industry, where artists handling people and concepts must work within financial structures imposed by managers from law or business backgrounds who can only see inefficiency.

CREATING CHARACTERS

Fiction, when not plot-driven, is driven by characters. Write down everything you can see or imagine about your characters as a way of getting to know them. Include in your list:

- What they look like

- What they wear

- What they like

- How they live

- Where they come from

- What experiences have marked them

- What they crave

- What they are trying to get or accomplish

- In what part of their spirit they ache

Strong characters will assist or even create the plot, but a plot will not create characters. Indeed, it may cramp and desiccate them.

WORK TO CREATE A MOOD

Settings that are bland or unbelievable compel the audience to struggle with disbelief at every scene change, something unavoidable in the theatre but eminently unnecessary when watching the screen. Using locations and sound composition intelligently can provide a powerfully emotional setting and hurl the audience into the emotional heart of a situation.

Whenever you are out and about, make a point of noting any place or situation that makes an impact. Later these can be incorporated into what you write. Like actors, good dramatists pay extremely close attention to what is around them and are constantly observing and researching in pursuit of their work. Making art is all about paying attention to life, something our escapist culture works so diligently to negate.

WRITE FOR THE CINEMA'S STRENGTHS

To avoid creating filmed theater, try turning conversations into behavioral exchanges that a deaf person could follow. This means writing as though for a modern, but silent cinema. Not only should dialogue be minimal, the storytelling itself should use images to drive the story forward. David Mamet protests that “most Hollywood films are made … as a supposed record of what real people really did” (On Directing Film, New York: Viking Penguin, 1992, p. 2). Mainstream features tend to be expository realism, a stream of passively informational coverage that occupies our attention without challenging our judgment or imagination. Mamet advocates telling a story in the way that “Eisenstein suggested a movie should be made. This method has nothing to do with following the protagonist around but rather is a succession of images juxtaposed so that the contrast between these images moves the story forward in the mind of the audience” (Mamet's emphasis). He goes on to say:

You want to tell the story in cuts, which is to say, through a juxtaposition of images that are basically uninflected. Mr. Eisenstein tells us that the best image is an uninflected image. A shot of a teacup. A shot of a spoon. A shot of a fork. A shot of a door. Let the cut tell the story. Because otherwise you have not got dramatic action, you have narration…. Documentaries take basically unrelated footage and juxtapose it in order to give the viewer the idea the filmmaker wants to convey. They take footage of birds snapping a twig. They take footage of a fawn raising his head. The two shots have nothing to do with each other. They were shot days or years, and miles, apart. And the filmmaker juxtaposes the images to give the viewer the idea of great alertness…. They are not a record of how the deer reacted to the bird. They're basically uninflected images. But they give the viewer the idea of alertness to danger when they are juxtaposed. That's good filmmaking. (On Directing Film p. 2)

This approach produces a dialectic of images and action that challenges you to discern the underlying authorial intent. It also happens to reflect daily experience in which our attention, combined with the assessments we make, causes us to jump from object to object to person to face to hand to doorway—and so on. We can only interpret people by telltale details of their external appearances and deeds. Perhaps this is why Herzog did not telephone or write to his beloved mentor, Lotte Eisner, when she lay sick, but trudged on foot from Munich all the way to her bedside in Paris.

Characters in a movie should be seen in action; their actions should give clues to their inner tensions. When they speak it should be to act on each other. They should not speak for the sake of realism or atmosphere, and never because their author needs to speak through them. (If you want to send a message, use Western Union.) Dialogue is best when it is a form of action, and sparse dialogue raises words to high significance.

These are widely held views for you to consider. Decide what qualities you really enjoy on the screen and regulate your filmmaking with creative limitations to take advantage of them.

TAKING STOCK

After some exploratory writing, distill a dramatic premise. This is a sentence or two encapsulating the situation, characters, and main idea on which the whole movie is founded, such as, “An unfulfilled man adopted as a child is now having a troubled marriage. He sets out to find his biological mother. So different is she from what he imagined that he returns to his wife with new appreciation.”

Next make a step outline, which is a third-person, present-tense description of each sequence's action with dialogue summarized and a new paragraph for each sequence. Quite often a full draft of the screenplay precedes the step outline, which becomes a defining process rather than a planning one. Reducing your ideas to their essence allows you to gain control over what the script is truly about. It sounds paradoxical that writers should need to discover their own work's themes and meanings, but the creative imagination functions on different levels, and some of its most important activity takes place beyond reach of the conscious mind.

The summarizing, winnowing process of making outlines and concept statements is a discipline that will raise the submerged levels into view and make them more useful. The amended step outline and premise you make after a new draft will energetically point the way to your next bout of revision and rewriting. Winnowing and summarizing makes analysis and development inevitable. Only when the characters have been created and the action and plot roughed out is it wise to begin a screenplay.

SCREENPLAY: FORM FOLLOWS FUNCTION?

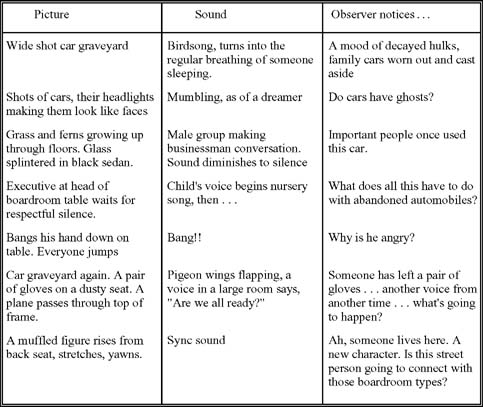

Unfortunately, because of the priorities and theatrical layout of the conventional screenplay, dialogue appears to be the major component. Here form doesn't follow function, form swallows function. Anyone trying to write in the Eisenstein mode is impeded, not helped by the prevalence of dialogue. A better way to draft initial ideas is to use the split-page format, adding a third column in the early stages of writing where you draft the Observer's developing perceptions, as in Figure 8-2.

Using this layout, you can work out what you want your audience to think, feel, question, decide (both rightly or wrongly), or remember from earlier in the film. The word processor's drag-and-drop function is excellent for experimentally moving materials around, but an agreeably low-tech alternative is to put your shots or sequences on index cards and move them around on a large table. Being equipped to experiment with ideas and intentions is vital to developing your own creative process and style. If you have special qualities as a storyteller, here rather than during shooting is where they will emerge.

WITH THE AUDIENCE IN MIND

If the drama you write is to get beyond the egocentricity of therapy, you will have to consider your audience intensively. This does not lead automatically to exploiting them or to some kind of fatal artistic compromise. It simply means trying to conceive works that participate in modern thought and modern dilemmas, prompt pertinent questions and ideas, cut across conventional thought, and resonate vividly in the hearts and minds of those watching your movie.

The only real way to picture this audience is to write for an audience of people very much like yourself in terms of their values and intelligence, but who

do not have your specific experiences and knowledge. Some would-be filmmakers by nature share much with the greater world, and some share little. There is nothing you can do about this except to embrace living and struggle mightily to leave the cocoon we all grow up in. Popularity in the cinema (or out of it) is nothing you can plan. All you can do is to use all your potential, take all the risks you need to take, and be true to yourself. If you make “Nothing human is alien to me” your creed, you will have a lifetime's work ahead, opening your mind to the human condition. Walking that road with all your heart will put you in touch with many good companions and reveal what is awful and wonderful in being human. This willingness to see comprehensively is at the very center of the artistic process.

STORY LOGIC AND TESTING YOUR ASSUMPTIONS

During the composition process you write from experience, imagination, and intuition, as well as assumptions stored in the unconscious. What is least certain is not the original experience or what you want to say about it, but whether your intentions will get across to the audience. Most miscommunication arises from being unaware of assumptions the audience can't or won't share and failing to provide a timely exposition as framing. For instance, though a screenwriter knows her character Harry would never perjure himself in court, her audience knows nothing of the sort. His honesty must first be established (the word establish appears a lot in screenwriting). To do this she might make Harry go back into a store after unthinkingly carrying a newspaper out with his groceries. Now his honesty is attested by his action of paying for it. She can even make him a white-collar criminal who has siphoned thousands from his corporation but who still goes out of his way to pay for his newspaper at the corner store. Complex moral codes are always interesting.

A story is a progression of logic that raises questions and offers clues, the full significance of which is often skillfully delayed. This logic you design and test through your planning process's third column. You will need to fulfill the audience's basic expectations for every human situation you set up. For instance, a film about a man adopted in childhood who searches for his biological mother would hardly remain credible if he failed to look for his birth certificate and never questioned his foster parents. These are basic steps that you either show or establish that they have been accomplished without satisfactory result.

Later, when our adoptee finds his mother, it would be equally illogical for him to become happy and fulfilled. Everyone of any maturity knows that people finding their biological parents have very mixed emotions, not the least of which are pain and anger. Lasting euphoria is untrue to human nature and makes the character simple-minded. Either the character or the moviemakers are naïve. If it's the latter, the audience will quickly realize they are smarter than the movie—and move on.

CREATING SPACE FOR THE AUDIENCE

Whether a story is told through literature, song, stage, or screen, the successful storyteller always creates significant spaces that the audience must fill from its own imagination, values, and life experience. Unlike the reader of a novel, film spectators do not have to visualize the physical world of the story, so it's all the more important that they speculate about the characters' motives, feelings, and morals. As a painting implies life beyond the edges of its frame, so dramatic characters and the ideas they engender should go beyond what we can see and hear.

CREDIBILITY, MINIMIZING, AND RAISING STORY TENSION

A fictional world, though self-contained, still runs according to rules drawn from life at large. The writer cannot capriciously violate the audience's knowledge of living. The story and its characters must be interesting, representative, and consistent if they are to remain credible. Other genres, such as documentary or folk tale, are hardly less free; each is true in some important way to the spirit of reality, and all are governed by rules the audience recognizes as “true.” Paradoxically this means the coincidences that occur in life become suspect in fiction.

While you write, anything you want to imply must first be named and fully explored before you move to minimize it. The writer always knows far more than he or she shares with the audience, but initially it is best to over-specify. Arthur Miller's plays start out at 800 pages before he cuts and compresses them down to a manageable stage time. Good storytellers withhold whatever they can and as long as possible because successful storytelling depends on creating tension and anticipation. Wilkie Collins, the father of the mystery novel, put it succinctly: “Make them laugh, make them cry, but make them wait.”

DIRECTING FROM YOUR OWN SCREENPLAY

If you are directing from your own script, work hard to distance yourself by exposing it to tough criticism. By carrying out all available analytical steps you can, with difficulty, gain an objective understanding of your own work. Be as ruthless with its faults as you would with anyone else's work. Unless you have learned to be professionally rigorous with your own writing, there will be many unexamined assumptions waiting to explode later into full-blown problems, and these, under public exposure, can badly sabotage the writer-director's confidence and authority.

YOUR WORK IS NOT YOU

Your writing is not you; it is only the work you did at a particular moment in your life. Your work is an interim representation. The next piece will show changes; it will be a little stronger and sharper. Truffaut admitted late in life that it is just as difficult to make a bad film as a good one, and he became a kinder critic after he had experienced the failures that prepare us to succeed. The integrity and perseverance of the explorer is what matters.

Keep going, no matter what. All writers say one thing: You must write to a schedule. Some days it produces bad writing. Some days, trying to write produces little or nothing. Other days it pours out. But you must learn to love the process and make yourself keep writing. Good writing only comes from rewriting bad writing.

INVITING A CRITICAL RESPONSE

Exposing your work in its different stages to criticism from trial readers or audiences is an important part of confirming that you are in touch with a first-time audience. Developing a story in isolation from feedback is risky and can be catastrophic. Getting confirmation that your instincts are right isn't difficult and is usually energizing.

TEST EXHAUSTIVELY ON OTHERS

It is a good practice to pitch one's ideas to anyone who will listen and be critical. If “the unexamined life is not worth living,” the unexamined story idea is not worth filming. Hearing yourself is the very best way to see your ideas from another's point of view. Repeatedly exposing your ideas to skeptical listeners also flushes out the clichés in your thinking (the power of positive embarrassment!). After all, your first thoughts are the same junk as everyone else's. Original ideas come to those who work hard at rejecting the unoriginal.

As with initial ideas, so with the screenplay. In seeking responses:

- Find mature readers whose values you share and respect.

- Keep your critics on track; you cannot be too interested in the film the respondent would have made.

- Ask what he or she understands from the script.

- Ask what the characters are like.

- Ask what seems to be driving them.

- Ask which scenes are effective.

- Ask which are not.

From this process you should acquire a complete and accurate sense of what the audience knows and feels at each stage of the proposed film. Critical readers will have to be replaced over time as they become familiar with the material. Remember, shooting an imperfectly developed screenplay is opening a Pandora's box of problems. It's heartbreaking to try curing them in the cutting room when it's too late.

ACT ON CRITICISM ONLY AFTER REFLECTION

In an audience medium, the director hopes for understanding by a wide audience whose experiences do not debar them from entering the most arcane world if it is carefully presented. Seeking responses to a script can be very misleading and also a test of self-knowledge. If you resist all suggestions and question the validity of the responses, you are probably insecure. If you agree with almost everything and set about a complete rewrite in a mood of self-flagellation, or worse, scrap the project, it means you are very insecure. If, however, you continue to believe in what you are doing but recognize some truth in what your critics say, you are progressing nicely. There will still be plenty of anguish and self-doubt. No gain without pain, they say.

Never make changes hastily or impulsively. Let the criticism lie for a few days, then see what your mind filters out as valid. When in doubt, delay changes and don't abandon your intentions. Work on something else until your mind quietly insists on what must, or must not, be done.

Do not show unfinished work to family or intimates. They will want to save you by getting you to hide your faults and naiveté from public view. Almost as damaging as reckless criticism is total, loving, across-the-board praise. The best way to show friends and family your work is with a general audience whose responses will help shape your friends and family in theirs. How many artists have had nothing but resistance and dissuasion from their family only to see it all magically evaporate when they hear an audience clapping (“Well, now, I never thought you'd do anything with that damned guitar…”).

TESTING WITH A SCRATCH CAST

Before proceeding to production you should assemble a scratch cast to read the script through, preferably with a small, invited audience of friends who will tell you candidly what they think. Each actor, however inexperienced, will identify with one character and show your script in an unfamiliar light. You should be able to wholeheartedly justify every word of dialogue and every stage direction in the script.

Large cities with a theater community often have screenplay readings and Writers' groups that exist to critique each other's work. Actors and theater organizations usually know about such facilities, as do film schools and film cooperatives.

REWRITE, REWRITE, REWRITE

Be ready to keep changing the screenplay all the way up to the day of shooting. A script is not an artwork with a final form; it is more like plans for an invasion that must be altered daily in light of fresh intelligence. Finished films cannot be product-tested with audiences the way plays can, so testing and reshaping must be accomplished during the script development and cast rehearsal periods. Editing, compressing, or expanding your material where needed, simplifying, and even wholesale rewriting will shape the material to take advantage of the way players enact the piece. Feature films I have worked on were regularly undergoing rewrites the day before shooting. Writers loathe this compulsive rewriting, but their standards for completion arise from habits of solo creation, while filmmaking is an organic, physical process that must adapt to the unfolding reality of cast and shooting—in both their negative and positive implications.

Rewriting is frequently omitted or resisted by student production groups because of inexperience or because it threatens the writer's ego. If this happens, the director should take over the script and alter it as necessary. In the professional world, the writer delivers a script and then loses control of it. There is a good reason for this, but few writers will agree.

FIGHT THE CENSOR AND FINISH

Finishing projects is very important. Work left incomplete is a step taken sideways, not forward. It is tempting halfway through a project to say, “Well, I've learned all I can learn here so I think I'll start something new.” This is the internal censor at work, your hidden enemy who whispers, “You can't show this to other people, it isn't good enough; the real you is better.” Your work seldom feels good for long, but do not let that make you halt or change horses. Only intermittently will you feel elation, but finishing will always yield satisfaction and knowledge.