CHAPTER 15

SPACE, STYLIZED ENVIRONMENTS, AND PERFORMANCES

SPACE

Film abridges time in the interest of narrative compression and can be equally selective with space. A protagonist eating dinner who suddenly remembers he hasn't put a coin in the parking meter will not be shown covering every step on his way to rectify the situation. Instead we will see him leap to his feet, his dropped spoon splashing soup, follow his feet running downstairs, then cut to join him in the middle of an argument with the meter maid. Even when locations are used to set our expectations about characters, the movie may only show us key aspects. Three scenes in a baronial hall will be set against the fireplace, the great stairway, and a doorway flanked with suits of armor; our imagination will create the rest of the space. Afterward we may distinctly remember seeing a wide shot of the whole hall, though it is a point of view supplied by our ever-ready imagination.

In Scorsese's black comedy After Hours (1985), the hapless office worker Paul escapes one dark, tangled New York situation only to fall into a worse one, and no location is shown more than minimally. It feels afterward as if you have seen every inch of Kiki's studio, but Scorsese actually gives us very little. The spectator is always completing what has been suggested, and with only a few well-chosen clues our minds will construct a whole town, as in David Lynch's Blue Velvet (1986). Every setup in his small town America is obviously and garishly contrived to be surreal, and this speaks of Lynch's origins as a painter. The film's early and brilliant predecessor is Lang's Metropolis (1926), in which the stylized environment is so pervasively visionary that it becomes a leading component in the film's formal argument.

Expressionism, especially in a film set in the present, creates a reality refracted through an extreme subjectivity. Lynch's first film Eraserhead (1978), about an alienated man reacting to the news that his girlfriend is going to have a baby, takes subjectivity to the limits of imaginable psychosis. Stylization is often present in the sound treatment, and Eraserhead also makes full and frightening use of the potential of sound. As Bresson said, “The eye sees but the ear imagines,” and our imagination is the ultimate dramatist. (Notes on Cinematography, New York: Urizen Books, 1977). It is what we imagine that is most memorable and moving.

Film is such a relativistic medium that specific aural or visual devices can only be judged in their specific contexts, something beyond the scope of this book. This chapter will touch some issues that arise constantly for the film author and suggest some guidelines that show, I think, that point of view and environment are inextricably intertwined. Making rules and drawing demarcation lines between the realistic and the stylized, subjectively observed environment is too ambiguous unless tied to a specific example. Even then, a detectable stylization may be traced to nothing more remarkable than a choice of lens, a mildly unrealistic lighting setup, or an interestingly unbalanced composition.

STYLIZED WORLDS

A genre is a specialized world, and stylization serves to create that world by reflecting the special way in which characters perceive and interact with their environment. This illuminates their temperaments and moods and makes their world a projection of their collective reality. In Polanski's chilling Repulsion (1965), the apartment occupied by its paranoid heroine becomes the embodiment of threatening evil. Logically you see how events are being created by her deluded mind, but you are nonetheless engulfed by what she perceives. The outcome is a sickeningly unpleasant sense of the psychotic's vulnerability. All this is demonstrated by the film's Storyteller—presumably for a larger purpose than merely to prove his power over our emotions. That Polanski's wife was later murdered raises unanswerable speculation about the roots of art in its maker's subconscious.

The screen does not and cannot render anything objectively because time, space, and the objective world are all refracted through particularities that may be human, technical, or just plain random. The outcome is a partly deliberate, partly arbitrary construct. Every aspect of a complex film is likely to resonate with every other one, like the stresses in a tent when one guy rope is tightened. For this reason alone, film has eluded attempts at objective analysis.

These chicken-or-egg questions are irrelevant to an audience, but bothersome to anyone trying to gain an overview of authorial method. The best advice is to accept that, no matter what film histories and books of criticism say, your only control over a live-action film is to abort it. To control a film is like trying to control your life. You can't control either, but you can guide them. Your films will be a true record of how successfully you envision something and then capitalize on chance, which is why this book stresses planning a vision, advancing your self-knowledge, collaborating with others, and being willing to improvise.

The ordinary viewer, however, sees a clear spectrum of possibility—with films of objective affect at one end and films of invasively subjective impact at the other. As if sampling Mexican food, let's start with mild and move toward hot.

OCCASIONALLY STYLIZED

In mainstream, omniscient cinema the stylized environment usually makes only a passing appearance—perhaps as a storytelling inflection to point out a character's temporary unbalance (euphoria, fear, insecurity, etc.) or to share confidential information with the audience, as a novelist might do in a literary aside. Withheld from characters, this privileged information (symbolic objects, foreshadowing devices, special in-frame juxtapositions) heightens tension by making us anticipate what the characters do not yet know is in store. By using a character's subjective vision minimally, realism lets us enter the main character's reality without giving up our observer's superior sense of distance and well-founded judgment. In the famous shower scene in Psycho (1960) we temporarily merge with the killer's eyeline after he begins stabbing. Then the point of view switches to show the last agonized images seen by Janet Leigh's character. Finally, the killer runs out, and as Janet Leigh's character is now dead, we are left with the Storyteller's point of view: alone with the body in the motel room.

This brief foray into immediate, limited perceptions—first of the killer, then of his victim—is reserved for the starkest moment in the film, when Hitchcock boldly disposes of the heroine. Elsewhere we are allowed more distance from the characters. Were we to remain confined to the characters' points of view, we would be denied Hitchcock's signs and portents of the terror to come. Often a storyteller raises the audience's awareness above that of the characters themselves and makes of the audience a privileged witness.

The deranged or psychotic subjectivity of Psycho and Repulsion is of course a favorite mechanism for suspense movies. Many of the films listed in previous chapters under single-character point of view (POV) expose us only sparingly to the POV character's circumscribed vision, leaving most of the drama to be shown from a more detached standpoint. In Carpenter's Hallowe'en (1978) we mostly identify with the babysitter, but occasionally circle and stalk her along with the vengeful but unseen murderer, occupying his reality even to the point of sharing the sensation of his breathing. While the switch to a subjective POV catapults us into vulnerable perspectives at times of peak emotion, an audience's overall empathy builds in response to the character's whole situation, not just at peaks or during close-ups. The island scene in Carroll Ballard's The Black Stallion (1979) creates the boy's love for the stallion through a lyrically edited vision of the horse galloping free in the waves of the island shore, yet the camera is usually distant from both boy and horse.

So far we have dealt with movement from a safe base of normalcy into a character's subjectivity and back again, just as the close-up takes us temporarily closer than would be permitted in life to explore some development of high significance in a character or (in the case of an object like a clock or a time bomb) some high significance to the mood or advancement of the story.

You must rely on the full range of storytelling to do this, not just editing. Indeed, to avoid stereotyped thinking about camera coverage and editing, it's important that you closely research what lies behind an audience's identification with a particular character. While getting an audience to identify with a main character is usually desirable, it is emphatically not the only purpose of drama. Brecht insisted that drama also exists to spur thought, memory, and judgment, and these, he contended, were in abeyance whenever the audience ceded their identity to that of a hero. But Mother Courage, for all her universality, is still a woman in a series of predicaments, and we must still empathize with her if we are to relate to the very human decisions she makes and are to make political judgments about emotion and expediency.

Sympathy and involvement in a film character's situation don't automatically arise because you happen to see from a character's location in space; they come about because we have learned from her actions what she is made of and from her situation what she must still face. Stylized camera coverage and editing do not alone create this, but they do serve it.

FULLY STYLIZED

Some films—to the purist, maybe all—set aside realism for a stylized environment throughout. Usually such a film is deliberately distanced in time or place. Period films fall readily into this category, from Griffith's Birth of a Nation (1915) and Victor Fleming's Gone with the Wind (1939) to more recent examples such as Anthony Minghella's The English Patient (1996) or Ang Lee's fable set in ancient China, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000).

Because we more readily grant artistic license to what is filtered through imagination or memory, any story profits from being distanced in time and place from what is familiar. Indeed the word legend is defined as unauthentic history. The cinema is thus furthering the notion of oral tradition in which actual events are freely shaped and embellished to serve the narrator's artistic, social, or political purpose.

ENVIRONMENTS

EXOTIC

Another way to achieve tension between figures and their environment is, instead of transporting the story in time, to place them in a specialized or alien setting, such as Bogart and Hepburn in Africa for Huston's African Queen (1951) or Antonioni's L'Avventura (1960), which imprisons its urbanites on an uninhabited island. Whenever the topic is a confrontation between antagonistic values, an alien setting allows the film to be impressionistic and create powerfully subjective moods. Vincente Minelli's An American in Paris (1951) allowed Gene Kelly to make Paris into a dream city of romance, while John Boorman's Deliverance (1972) thrust his four Atlanta businessmen into Appalachia's wilderness to put their “civilized” values to the test of survival. A quite different setting distinguishes Spike Jonze's Being John Malkovich (1999) in which an unemployed puppeteer finds a way into the actor John Malkovich's head and rents out the view from his eyes.

FUTURISTIC

The flight from the here and now includes not only myth but also the future. Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1926) is the classic, but there is no shortage of other good examples. Chaplin's Modern Times (1936), Godard's Alphaville (1965), Kubrick's 2001 (1968), Truffaut's Fahrenheit 451 (1966), Lucas' Star Wars (1977), Scott's Blade Runner (1982), and Gilliam's Brazil (1986) all hypothesize worlds of the future. Each shows Kafkaesque distortions in the social, sexual, or political realms that put characters under duress. Plucked from the familiar and invited to respond as immigrants to a world operating under different assumptions, we are often shown the totalitarianism of dehumanized governments made powerful through technology. However, in the drive to illustrate a thesis, secondary characters often emerge as unindividualized, flat archetypes. If tales are traditionally vehicles for exploring our deepest collective anxieties, the realm of the future seems reserved for nightmares about the individual alone during a breakdown in collective control.

EXPRESSIONIST

Some films construct a completely stylized world. Kubrick's strange, violent A Clockwork Orange (1971) is a picaresque tale played out by painted grotesques in a series of surreal settings. Even if you quickly forget what the film is about, the visual effect is unforgettable and owes its origins to the Expressionism of the German cinema earlier in the century. Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) borrowed its style from contemporary developments in the graphic arts, which explored a wholly altered reality—an endeavor utterly justified by subsequent events in Nazi Germany. In these films characters may have unnatural skin texture or move without shadows in a world of oversized, distorted architecture and machinery. Fritz Lang's Dr. Mabuse (1922) and Murnau's Nosferatu (1921) sought to create the same unhinged psychology with a more subtle use of the camera. The proportions of the familiar have utterly changed in these films, and we find ourselves enclosed in a fully integrated, nightmarish world expressing an alien state of mind. They made their political and satirical comment, much as Kokoschka, Grosz, and Munch did through the graphic arts of the 1920s and 1930s.

Whereas Travis Bickle in Scorsese's Taxi Driver (1976) insanely misreads a familiar world, the hero in an expressionistic film such as David Lynch's Blue Velvet (1986) tries to feel at home in an arbitrary and distorted cosmos. The audience joins him in setting aside normalcy for a heightened and subjective world vibrant with ominous metaphor. Central characters in expressionist films are often under attack by a world running according to inverted or alien rules and peopled by characters who neither reflect nor doubt. Expressionism is clearly akin to the fairy tale world of Hans Christian Andersen or the brothers Grimm. In the cinema, Victor Fleming's The Wizard of Oz (1939) stands out as the classic of the genre, and more recently Steven Spielberg has made a whole industry out of providing modern fairy tales, most notably E.T. (1982).

ENVIRONMENTS AND MUSIC

Past, future, or distant settings are easiest to selectively distort in the service of a biased caricature. But there are ways to remain in the present, yet display everyday transactions as heightened and non-realistic. Musicals are one way. Jacques Demy's The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), though visually formal and lyrical in composition and camera movement, tells a conventional small-town love story using natural dialogue. The difference is that it is sung, giving the effect of a realistic operetta (if that is not a contradiction in terms). The Gene Kelly films do something similar, but with dance, and they use unashamedly abstract, theatrical sets. Busby Berkeley's dance films, on the other hand, veer toward fantasy by merging human beings into kaleidoscopic patterns.

Music itself, when its use surpasses conventional mood intensification, can impose a formal patterning of emotion on the life onscreen. In Losey's The Go-Between (1971), Michel Legrand's exceptionally fine score starts with a simple theme from Mozart and develops and modulates it hauntingly, carrying us through a boyhood trauma and onward to the ultimate tragedy—the emotionally withered, unused life of the old man who survives. Peter Greenaway's use of Michael Nyman's minimalist scores in The Draughtsman's Contract (1983), A Zed and Two Noughts (1985), and Drowning by Numbers (1991) powerfully unites the mood of characters moving like sleepwalkers through worlds dominated by mathematical symmetry and organic decay.

THE STYLIZED PERFORMANCE: FLAT AND ROUND CHARACTERS

Perhaps the least stylized performances are those caught, documentary fashion, by a hidden camera, as Joseph Strick did in The Savage Eye (1959). Here we face a paradox: If the subject is unaware he is being filmed, he is not acting but being. Performers know they are performing and make choices about what they present, consciously and unconsciously adapting to the situation. All performance is therefore stylized to some extent.

Here I'll draw a working distinction between the performance that strives for realism—the art that hides art—and that deliberately heightens for dramatic effect. The adaptations of Dickens' novels, such as George Cukor's David Copperfield (1934) or David Lean's Oliver Twist (1948), have a young person as their POV character and use him as a lens on the adult world. Fagan, Bill Sykes, and the other thieves verge on the grotesque, while Oliver remains a touchingly vulnerable innocent caught in their web. These are good examples of what E.M. Forster called flat and round characters, the round character being complex and psychologically complete and the flat characters being more dimensionless because they are filtered through Oliver's partial and vulnerable perception.

How much a secondary character should be played as subjective and distorted can be decided fairly easily by examining the controlling POV. In Welles' version of Kafka's Trial (1962), it is the character of Joseph K. with whom we identify and through whose psyche all the characters are seen. Likewise, in The Wizard of Oz (1939), Glenda the Good Witch and the Wicked Witch of the West are designed to act in oppositional ways upon Dorothy and dramatize her conception of benevolence and evil.

In films in which a polarization is implied between the POV character and those in the surrounding world, oppositional characters or antagonists can be analogues for the warring parts of a divided self. Often in dialectical opposition

to each other, they will bear on the (usually vulnerable) main character like the spokes of a wheel in relation to its hub. The morality play form, with its melodramatic emphasis on setting the innocent adrift among hostile or confusing forces, is a particularly useful way to externalize the flux within an evolving personality because the cinema, with its emphasis on externals, does not otherwise handle interior reality particularly well.

It is the writer's and director's task to set the levels of heightened characterization and to determine the nature and pressure of what each spoke must transmit to the hub or POV character. It will be crucial, too, that the level of writing and playing be consistent and that there be change and development throughout the film so that no part, whether spokes or hub, becomes static and therefore predictable.

Flat characters usually have simple characteristics and represent particular human qualities as they apply to a main character. They remind us of the early theater's masks and stock characters discussed in the section of Chapter 1 titled On Masks and the Function of Drama. Non-realistic or flat characters are likely to function as metaphors for the conflicting aspects of the round character's predicament and thus to forewarn us of a metaphysical subtext we might otherwise miss.

NAMING THE METAPHORICAL

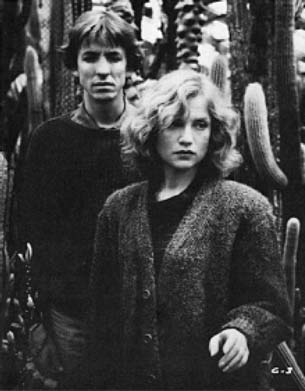

If characters play metaphorical roles in an allegory—and it is invariably revealing to analyze every script as though this were true—it is important for the director to find metaphors to epitomize each character and assign each character an archetypal identity. These are potent tools for clarification and action, and the process is equally useful for the worlds the characters inhabit. Paul Cox's Cactus (1985) portrays the developing relationship between an angry and desperate woman losing her sight and a withdrawn young man who is already blind (Figure 15–1). The man makes his refuge a cactus house, and she visits him there to see what he can tell her about her fate. The cacti are dry, hostile, and spiky, but also phallic, and the setting becomes emblematic of his predicament. In a sexually charged world, he has turned his back on intimacy and intends to survive self-punitively in a place devoid of tenderness or nourishment.

Having settings and predicaments dramatized, and explanatory metaphors in hand will greatly help you explain to actors how you want each to play their role and why. We shall explore this principle much more fully in upcoming chapters on analyzing the script and working with actors.