CHAPTER 29

MISE EN SCÈNE

PURPOSE

The French expression mise en scène (literally, putting into the scene) is a usefully holistic term for those aspects of directing that take place during shooting. mise en scène has to be decided globally and in broad outline for the whole script, and then each scene can be designed within the intentions of the larger structure. Globally or locally, mise en scène includes:

- Blocking, which includes planning positions of:

Actors in relation to each other

Action in relation to set or location

Camera placement in relation to actors and set - Camera

Filmstock and processing, or color settings (video)

Choice of lens

Composition

Movements

Coverage for editing - Image design

Use of color

Depth, perspective, and treatment of space

Lighting mood, and treatment of time of day and place

Frame design in terms of the scene's dramatic functions - Dramatic content

Rhythms (action rhythms and visual rhythms)

Point of view (whose consciousness the audience should identify with)

Motifs or leitmotifs

Visual or aural metaphors

Foreshadowing - Sound Design

Whether sound is diegetic or non-diegetic

What part sound plays as a narrative device

Whether it relays a subjective or objective point of view

Whose point of view it is

All this must eventually be planned in practical rather than intellectual terms. The director must know what options exist and how to eventually discuss them with the DP, who is undoubtedly the most important collaborator during the shoot. This is also a time when directors can fall completely under the spell of strong-minded DPs. And that would be another invitation to abdicate the director's role.

SURVEYING THE FILM

Translate each scene in your film into a brief content description, then annotate it with how you want the audience to feel about it, and you have a firm beginning. If possible, turn the list into a graph or storyboard showing what the audience must feel from scene to scene, and then you can think about how the Storyteller must tell the tale to make this happen. Once you have an overall strategy, you can move to designing individual scenes.

LONG-TAKE VERSUS SHORT-TAKE COVERAGE

Covering a scene means shooting enough variation of angle and subject so you can show it to advantage on the screen. Depending on the nature of the film this can mean long, intricately choreographed takes lasting an entire scene as used by Hitchcock in Rope (1948), or it might call for a flow of rapidly edited images as favored by such disparate filmmakers as Eisenstein in The Battleship Potemkin (1925), Nicholas Roeg in Don't Look Now (1973), and just about any MTV music video.

The long-take method: generally requires a mobile camera and intricate blocking of both camera and actors to avoid a flat, stagey appearance. Because you cannot cut around anything, it requires virtuoso control by actors and technicians as any errors consign an entire take to the trashcan. There is also a risk that only shows up in the first assembly: Because no control of individual elements is possible within any scene, the editor cannot rebalance the rhythm of the performances or the pacing of the story. For a superb example of fluid camera control and blocking in long takes, see Jacques Demy's masterpiece, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). A story of lovers in a small French town when the upheavals in Algeria took recruits off to war, it is an operetta in which all dialogue is realistic and sung. Surprisingly this works very well. The film is also masterly in its design and use of color. Another that uses movement exceptionally well is Wim Wenders' Faraway, So Close! (1993). By this time the Steadicam™ body mount had been invented and DP Jürgen Jürges and Jörg Widmer, his Steadicam operator, took full advantage of the extraordinary handheld liberty afforded the ponderous 35mm camera.

The short-take method: makes the material more evidently manipulated because it requires frequent cuts. At MTV's frenetic extreme the viewer is bombarded with fragments of action from which to infer the whole. In short-take coverage generally, shots are edited together to create rhythm, juxtaposition, and tension, but for the audience, any cut always takes energy to interpret. Rather than rely on blowhard editing, many directors choreograph their mise en scène as individual shots containing complex blocking. Following the example of the wise and the foolish virgins, they also shoot safety coverage in case longish takes are flawed or their inalterable pacing fails.

FIXED VERSUS MOBILE CAMERA

A camera on a tripod is able to zoom in and hold a steady close shot without physically crowding the actor. On the other hand, it cannot dolly or crab to a better vantage point. Mounting the camera on a dolly or crane allows smooth movement through a predetermined cycle but requires great precision from both crew and cast, who must hit predetermined chalk marks on the floor if composition and focus are to hold up. Here the casualty may be spontaneity in the cast. A dolly and its crew are also apt to make some noise, so you may pay with more sound postproduction work and extra takes where floor creaks obscure dialogue.

Intelligent handheld camerawork may be the only solution if you are to shoot a semi-improvised performance under a time constraint. The handheld camera gives great mobility but at the price of a certain unsteadiness. A Steadicam in the right hands can solve all of these problems. In the hands of someone inexperienced, however, you can lose hours.

SUBJECTIVE OR OBJECTIVE CAMERA PRESENCE

The two kinds of camera presence, the one studied, composed, and controlled, and the other mobile, spontaneous, reactive, and adaptive to change, will each give a different sense of an observing presence. Each implies a relatively subjective or objective observation of the action. Camera-handling alone may thus alter the voice of the film, making it either more or less personal and vulnerable. Maintaining either mode may become dull, while shifting justifiably between them can be very potent.

RELATEDNESS: SEPARATING OR INTEGRATING BY SHOT

Composition and framing alter a scene's implications drastically. Isolating two people, each in his own close shot, and then intercutting them has a very different feel than intercutting two over-shoulder shots in which the two are always spatially related. Their relationship in space and time appears less manipulated by the filming process than in over-shoulder shots. In the single shots, the observer is always alone with one of the contenders and inferring the unseen participant. In cinema this isolation is the exception, for limitations of frame size usually compel using precious screen space to the utmost by packing the

frame and showing the spatial relationship between everything and everybody (Figure 29-1).

HAVE THE COURAGE TO BE SIMPLE

Viewing heavily edited scenes is hard work, so a strong reason to move the camera (or subjects in relation to camera) is to increase the amount that can happen in a single take, which conserves on the need for associative editing. Other camera movements are necessary to preserve composition and framing when characters are on the move or to reveal something or someone formerly out of frame. The very best lessons in camera positioning and movement lie waiting in the best films in your chosen genre. Study them. You'll be surprised how good simple films look when they rely on a good story, good acting, and inventive blocking rather than swishy camerawork.

THE CAMERA AS OBSERVING CONSCIOUSNESS

Treat the camera as a questing observer and imagine how you want the audience to experience the scene. If you had a scene in a turbulent flea market, it would not make sense to limit the camera to carefully placed tripod shots. Make the camera adopt the point of view of a wandering buyer by going handheld and peering into circles of chattering people, looking closely at the merchandise, and then swinging around when someone calls out.

If, instead, you are shooting a church service, with its elaborate ritualized stages, the placing and amount of coverage should be rock steady because that is our usual experience in such a setting. Ask yourself whose point of view the audience is mostly sharing. Where does the majority of the telling action lie? With the newcomer? The priest? The choir or the congregation?

THE STORYTELLER'S POINT OF VIEW

David Mamet, in his On Directing Film, has protested that too much fiction filmmaking consists of following the action like a news service. Do you want to document happenings or connect like a Storyteller? The first is passive, value-free surveillance, and the second involves inflection, having an active purpose, raising critical questions, and implying a mind and heart at work. What identity will you give your Storyteller, and what singularity should we notice in your characters and their situations? These are not easy questions, but they will not answer themselves during shooting or editing.

Help is at hand when you call on the connotations of the word attitude. The attitude of the storytelling mind, intelligence, and heart is really the lens through which an audience experiences your story. How would you describe this attitude? What will it be like? What are the ironies and humor in its way of seeing? How will you make these show, because that slant must infuse the movie. Your Storyteller's attitude must show throughout, which means implying puzzlement, doubts, enjoyment, censure, opprobrium, delight, distrust, regret, fascination—whatever changing thoughts grip the Storyteller as he or she gives birth to the unfolding tale.

You have definite ideas about this from moving around during rehearsal and watching these newly born characters living the salient pieces of their lives. You watched and identified according to a pattern that's based on the intentions behind the writing and arises now from the chemistry of personalities and situation. You must remain sensitive to this. Is how you notice, what you notice, and what you feel being reflected in the video rehearsal coverage? If not, why not?

By pausing to dig into your impressions you can go further toward understanding their sources and their impact. You can use your mind to examine the heart, and come away more strongly convinced of who you are and what you have seen. A friend used to say, “Nothing is real until I have written about it.” Make a point of writing the Storyteller's part as the invisible Observer and further developing the symbiotic nature of the tale and the teller. They go together; one depends on the other. To create the Storyteller you have to bring the telling alive as well as the tale, that is, you must give it the integrity of a quirky human mind that sees, weighs, wonders, feels, and supposes as the story unfolds. Do that successfully, and your work will acquire the magical quality of humor and intelligence that characterizes work having soul. Not too many films have soul. It is an attribute to which audiences universally respond.

The encouragement to make films at all always comes from seeing special films. For heart and soul, see Jean-Pierre Jeunet's immensely popular Amelie (2001). It is a fable about a lonely Paris waitress who finds a box of old toys hidden behind the floorboards and sets out to return them to their owner. She discovers joy in anonymously contributing to other people's lives from a distance. Of course, if you do good, good eventually comes back to you, and she at last finds love. This funny, quirky film, made intimately around the presence of the enchanting Audrey Tautou, celebrates the Paris of 40 years ago and the extraordinary films that emerged during the era of the French New Wave.

In the struggle for narrative clarity and efficient plotting, the factory-like process of most filmmaking tramples the soul out of most work. Occasionally a film appears whose boldness of conception and execution transcends the process, and Amelie is one such work. Of course, there can be no formula for making a film with a soul. It lies in an integrity in your way of seeing. Like everything else in fiction, this can be distilled, heightened, and enjoyed in the making, all to the greater good. But it takes a director with a clear, strong identity—one not overwhelmed by the people and process. You have your work cut out, don't you?

APPROACHING A SINGLE SCENE

SCRIPT, CONCEPT, AND SCENE DESIGN

Although influenced by limitations inherent to the setting or in the cinematographic process, a scene's design is based on its intended function in the script and your gut feelings about the scene. How, for instance, might you show a man who is being watched by the police get into his car and try to start it? Here is a checklist you can apply to any scene:

- What is the scene's special function in the script?

- What does the audience need to know about the scene's setup and spatial content:

At the outset of the scene?

Later? (How much later?) - What perspectives and relationships must be indicated through using space?

- What information can be left to the audience's deduction or imagination?

- What elements should be juxtaposed

Visually within each shot's framing?

Conceptually by editing shots together? - How much are characters aware of their predicament and what are each character's expectations:

At the start of the scene?

At its end? - Who learns and develops?

- Where is the scene's obligatory moment?

- Is there anything the audience but not the characters should learn?

- What is the ruling image or motif here?

- Is any foreshadowing called for?

- What visual design is called for in:

Amount and distribution of light?

Tonality?

Hue?

Costuming?

Set design?

Illusion of space—or lack of it? - What is the Storyteller's attitude to this scene compared with others?

Should the audience see our man being watched by police from the policeman's point of view or from a more omniscient one (that is, the Storyteller's) in which the audience, but not the man, notices the cop? This will probably be decided on plot grounds, but what the characters experience should influence your coverage, just as characters in real life influence whom you choose to watch in any given situation.

Now imagine a more complex scene in which a child witnesses a sustained argument between his parents. How should point of view be handled there? First, what does the argument represent? Is it “child realizing he is a pawn,” or is it “parents are so bitter that they don't care what their child can hear?” Is it what the child sees or how the dispute acts upon him that matters?

Questions like these determine whose scene it really is: the boy's, the father's, or the mother's. The scene can be shot and edited to polarize our sympathetic interest in any of these directions at any given moment in the scene. Remember that making no choice leads to faceless, expressionless filmmaking—technical filmmaking with no heart or soul. This is not what you want.

There remains a detached way of observing events, that of the Omniscient Storyteller. This point of view is useful to relieve pressure on the audience before renewing it again. Sustained and unvarying pressure would be self-defeating because the audience either becomes armed against it or tunes out. Shakespeare in his tragedies intersperses scenes of comic relief to deal with this problem.

To summarize: what is salient will vary with the scene depending on its contents, complexity, and what it contributes to the film as a whole. Defining what the Storyteller notices and feels helps you decide how to reveal what matters and makes everything less arbitrary. Here you've got to develop instincts and really listen to them.

POINT OF VIEW

WHOSE POINT OF VIEW?

Controlling point of view probably remains a baffling notion. As we said, it is not literally “what so-and-so sees,” though this may comprise one or two shots. Rather, it attempts to relay to the audience how a character in the film is experiencing particular events. Top priority will always be to ask whose point of view this scene favors. A great many of your decisions about composition, camera placement, and editing will flow from this.

POINT OF VIEW CAN CHANGE

Remember, point of view (POV) means the way our sympathy and curiosity migrates between patient and doctor, subject and object—even though finally the film is about the patient. To understand and care for the doctor, we need to share those paradoxical moments when he empathizes with our central character, vacating his own protected reality to enter that of the condemned man. A character who never temporarily relinquishes his own identity to something larger would be someone alienated or inhuman.

Decide POV by asking what makes dramatic sense to the Concerned Observer. Answers come from the logic of the script and from your instincts. There may be no overriding determinant, in which case the editor will have to decide later, based on the nuances of the acting and whether you've shot enough alternative coverage.

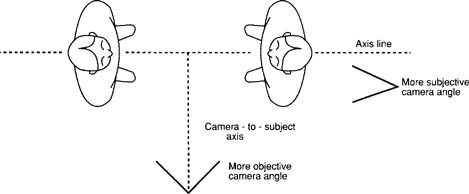

A reminder: Subjective POV shots tend to be close-ups and shots close to the axis or the line of psychic tension between characters. Objective POVs tend to be wider shots and farther from that line (Figure 29-2). These generalizations are no more than a rule of thumb because POV is oblique and impinges on the audience through a subtle combination of action, characters, lighting, mood, events, and context.

COMPROMISES: SPACE, PERCEPTION, AND LENSES

The art of the cinema gets delivered through a series of compromises made to accommodate the fact that the camera sees in two dimensions instead of three, and that its field of view is very limited compared with human visual perception. To compensate for this, we render the spirit of consciousness, not its actuality, by using associative techniques to counterpoint sound and images; we compress more in the frame and accomplish more in space and time than happens in real life.

CAMERA EYE AND HUMAN EYE ARE DIFFERENT

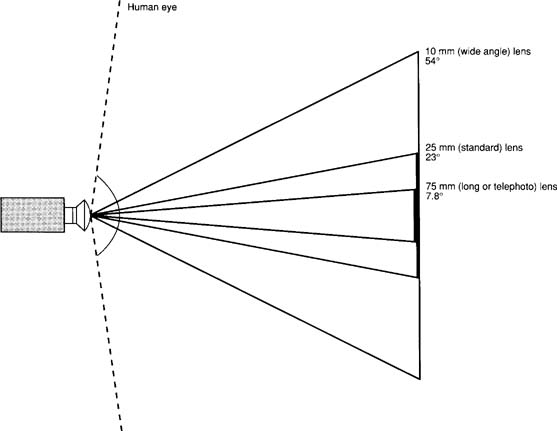

The eye of the beholder during rehearsals is misleading, for the human eye takes in a field of almost 180 degrees (Figure 29-3). Although a 16mm camera lens of 10mm focal length is called a wide angle when shooting in TV aspect ratio, it still only takes in 54 degrees horizontally and 40 degrees vertically. This means that a reasonably comprehensive wide-angle lens (before gross fairground distortion sets in) only has one quarter of the eye's angle of acceptance. This translates to a very restricted field of view indeed and one with resounding consequences for dramatic composition. Film aspect ratios are described later in this chapter.

FIGURE 29-3

Human eye's field of vision compared with much more limited angle of acceptance for 16mm camera lenses. Note that vertical angles of acceptance (not shown) are 25% smaller still.

We compensate for such limitation by rearranging compositions so they trick the spectator into the sensation of normal distances and spatial relationships. Characters holding a conversation may have to stand unnaturally close before the camera, but will look normal onscreen; furniture placement and distances between objects are often cheated, that is, they are moved either apart or together to produce the desired appearance onscreen. Ordinary physical movements like walking past the camera or picking up a glass of milk in close-up may require slowing by a third or more to look natural onscreen. Note, however, that comedy dialogue (though not necessarily movement) often needs faster than normal playing if it is to avoid looking slow onscreen. As always, screen testing helps you make all such decisions.

Packing the frame, achieving the illusion of depth, and arranging for balance and thematic significance in each composition can all compensate for the screen's limited size and its tendency to flatten everything. As the Hardy quotation mentioned previously says, “Art is the secret of how to produce by a false thing the effect of a true.”

ASPECT RATIO

This refers to the proportions of the image in terms of height versus the width. Early cinema had an aspect ratio of 1.33 :1, that is, it was 1.33 units wide to every 1 unit high. Television maintained roughly the same proportions. In the 1950s wide screen aspect ratios came along and today's cinema aspect ratios are 1.66 :1 (Europe) and 1.85 :1 (United States).

High definition television (HDTV) camcorders are designed to shoot wide screen, but less advanced camcorders, if they shoot in wide screen at all, do so by electronically chopping a band off the top and bottom of the image. This means the recorded image uses fewer pixels (picture cells inherent to the electronic imaging chip) than the standard ratio and is less satisfactory in terms of quality. Television viewers are by now familiar with the result, called letterbox format, in which the image seems to have shrunk, leaving unused black bands at the top and bottom.

The adoption of digital HDTV means that all film and video will in the future be shot wide screen. Cinemas and television sets will have similar aspect ratios, and directors and DPs will in the future compose for wide screen. This means that inherently wide pictorial matter, such as landscape shots and anything making horizontal movement, can take place more satisfactorily on the screen. Virtually everybody feels that wide screen allows for more interesting filming and that 1.33 :1 is restrictive compared with the wider formats.

CHOOSING LENS TYPE

This is an area some people find forbidding, but you don't need a physics degree to use lenses intelligently. As the standard reference, we call normal those lenses that give the same sense of perspective as the human eye, while the departures to either side of normalcy affect magnification and are called wide and telephoto. Analogies from everyday life show the basic differences:

These familiar optical devices allow us to pursue a range of dramatic possibilities in the camera lens. Compare the telescope image to that of the security spyglass, which allows the cautious householder to see if the visitor on the other side of the door is friend or foe.

The telescope: brings objects close; squashes together foreground, middle ground, and background; and isolates the middle ground object in sharp focus while foreground and background are in soft focus.

The security spyglass: brings in a lot of the hallway outside and keeps all in focus, but it produces a reduced and distorted image. If your visitor is leaning with one hand on the door, you are likely to see a huge arm diminishing to a tiny, distorted figure in the distance.

PERSPECTIVE AND NORMALCY

Our sense of perspective comes from knowing the relative sizes of things and judging how far apart they are in near and far planes. In a photo containing a cat and a German shepherd, we judge how far the dog is behind the cat from experience of their relative sizes. Human eye perspective is normal while other lenses alter this relationship radically. The focal length of a lens rendering perspective as normal onscreen will vary according to what camera format is being used:

| Format | Focal length for normal lens | ||

| 8mm | 12.5mm | ||

| 16mm | 25mm | ||

| 35mm | 50mm |

There is a constant ratio between the format (width of film in use) and the lens' focal length. The examples that follow discuss only 16mm-format lenses, the equivalent of which are found (though seldom calibrated) in many small-format video cameras.

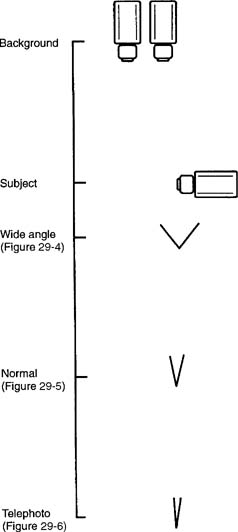

Normal perspective (Figure 29-4) means the viewer sees an as is size relationship between foreground and background trucks and can accurately judge the distance between them. The same shot taken with a wide-angle lens (Figure 29-5) changes the apparent distance between foreground and background, making it appear greater. A telephoto lens (Figure 29-6) does just the opposite, squeezing foreground and background close together. If someone were to walk from the background truck up to the foreground, the implications of their walk would be dramatically different in the three shots; all would have the same subject but offer a different formal treatment through the choice of lens.

PERSPECTIVE CHANGES ONLY WHEN CAMERA-TO-SUBJECT DISTANCE CHANGES

By repositioning the camera and using different lenses (as in Figures 29-4, 29-5, and 29-6), we can standardize the apparent size of the foreground truck, as shown diagrammatically in Figure 29-7. What this implies is that ultimately changes of perspective result only from camera-to-subject distance rather than the lens itself.

Now examine Figures 29-8, 29-9, and 29-10. Each is taken with a different lens but from the same camera position. The proportion of the stop sign in relation to the background portico is identical in all three. Perspective—size proportions between planes—has not changed, although we have three different magnifications. So indeed, perspective is the product of camera-to-subject distance, for when this remains constant, the proportions between foreground and background remain the same although the image was shot through three different lenses, with three different degrees of magnification.

MANIPULATING PERSPECTIVE

Using the magnifying or diminishing capacity of different lenses allows us to place the camera differently, and yet produce three similar shots (see Figures 29-4, 29-5, and 29-6); and when camera-to-subject distance changes, we can manipulate perspective. Wide-angle lenses appear to increase distance while telephoto lenses appear to compress the distance.

ZOOMING VERSUS DOLLYING INTO CLOSE-UP

A zoom is a lens having infinite variability between its extremes (say 10 to 100mm, which is a zoom with a ratio of 10:1). If you keep the camera static and zoom in on a subject, the image is magnified but perspective does not alter. With a prime (fixed) lens dollying in close, the image is magnified and you see a perspective change during the move, just as in life. One is movement, the other magnification.

LENSES AND IMAGE TEXTURE

Examine Figures 29-8 and 29-10. The backgrounds are very different in texture. Although the subject is in focus in both, the telephoto version puts the rest of the image in soft focus, isolating and separating the subject from its foreground and background. This is because the telephoto lens has a very narrow depth of field and only the point of focus is sharp.

|

Normal lens. |

|

|

FIGURE 29-5 Wide-angle lens. |

|

|

FIGURE 29-6 Telephoto lens. Foreground and background distances appear quite different in Figures 29-4 and 29-5. |

|

Conversely, a wide-angle lens (Figures 29-5 and 29-8) allows deep focus. This is useful when it allows you to hold focus while someone walks from foreground to background. Deep focus can be a distraction when its image drowns its middle-ground subject with a plethora of irrelevantly sharp background and foreground detail. We say that the telephoto has a soft textured background, while the wide angle has one that is hard. Lens characteristics can be limiting or have great dramatic utility, depending on what you know and how you use it.

WHY THERE IS A FILM LOOK AND A VIDEO LOOK

There are differences of appearance between film and video that derive from the size of the image-collecting area. A 35 mm-film aperture has many times as much area as a digital video (DV) camera imaging chip. The larger the image size at

|

Wide-angle lens. |

|

|

FIGURE 29-9 Normal lens. |

|

|

FIGURE 29-10 Telephoto lens. Figures 29-8, 29-9, and 29-10 are taken from a single camera position. Notice that the stop sign remains in the same proportion to its background throughout. |

|

the focal plane, the more refraction it takes and the more critical is the lens's depth of field. If you've ever looked at the image produced by a plate still camera, it is remarkable for two things: the negative (imaging) area is huge, and large parts of the image are soft focus, particularly when using a telephoto lens. The two facts are interdependent. That's why a home 8mm film camera hardly ever needed focusing. The imaging area was tiny and the angle of refraction between lens and film gate very narrow.

The German optical firm P + S Technik has produced the Mini35 Digital adapter (Figure 29-11). In a two-stage optical operation, the adapter uses interchangeable 35mm lenses to produce an internal image. This image is then copied and projected into the video camera's imaging path. The result is that the adapter preserves the focal length, depth of field, and angle of view of the 35mm format. It is available for the Canon XL1, XL1s, and Sony DSR PD150, VX1000, VX2000. You can read about it at www.pstechnik.de/. At an (expensive) stroke, it hands the videographer the lens choice and control of the 35mm cinematographer—and a larger camera that many prefer for handheld shooting. You may think the Canon XL range of DV cameras is already equipped for 35mm lenses. It's true they take 35mm lenses, but the camera's tiny imaging area discards much of the given image. You get manual lens control and superior acuity, but are back in amateur land so far as depth of field and angle of view are concerned.

LENS SPEED

Lens speed is a deceptive term. It has nothing to do with movement and everything to do with how much light a lens needs for minimal operation. A fast lens is one in which the iris opens up wide so the lens is good for low-light photography. A slow lens is simply one that fails to admit as much light. By their inherent design, wide-angles tend to be fast (say, f1.4) while telephotos tend to be slow (perhaps f2.8). A two-stop difference like this means that the wide-angle is operative at one-quarter the light it takes to use the telephoto. This may be the difference between night shooting being practical or out of the question. Prime (that is, fixed) lenses have few elements so they tend to be faster than zooms, which are multi-element. Primes also tend to have better acuity, or sharpness, because the image passes through fewer optics. Note that zooms have one optimal lens speed over their whole range.

CAMERA HEIGHT

The film-manual adage says that a high camera position suggests domination and a low angle, subjugation. There are other, less colonial-sounding reasons to vary camera height. A high or low camera angle may accommodate objects or persons in either the background or foreground, or accommodate a camera movement. This is covered in the upcoming section, Relatedness: Separating or Integrating by Shot. If you completed Chapter 5, Project 5-1: Picture Composition Analysis, taking as your subject a film as cinematically inventive as Orson Welles' classic Citizen Kane (1941), you saw many occasions when the departure from an eye-level camera position simply feels right. Often there is a dramatic rationale behind the choice, but don't turn them into a filmmaking Ten Commandments.

The veteran Hollywood director Edward Dmytryk in his book On Screen Directing makes a persuasive case for avoiding shots at characters' eye level simply because they are dull. There may also be a psychological reason to avoid them. At eye level, the audience feels itself intruding upon the action, just as we would feel both threatened and intrusive by standing in the path of a duel. Being above or below eye level positions puts us safely out of the firing line. This is something to remember whenever your camera approaches the axis.

LIMIT CAMERA MOVEMENTS

Most camera movements, apart from zooming, panning, and tilting, spell trouble to your schedule unless you have an expensive dolly and tracks and a highly experienced team to operate them. Understandably, student camera crews love to hire advanced camera support systems because it gives them practice and makes them feel professional. The price of this education may be a production repeatedly paralyzed while someone attempts to perfect a complex move with nothing beyond egocentric virtuosity to offer the story.

ADAPTING TO LOCATION EXIGENCIES

It's hard to recommend rules for camera positioning and movement because every situation has its own nature to be revealed and its own unique limitations. The latter are usually physical: windows or pillars in an interior that restrict shooting in one direction or an incongruity to be avoided in an exterior. A wonderful Victorian house turns out to have a background of power lines strung across the sky and has to be framed low when you wanted to frame high. Even when meticulously planned, filmmaking is always a serendipitous activity and often your vision must be jettisoned and energy redirected to deal with the unforeseen.

For the rigid, linear personality, this constant adaptation is unacceptably frustrating, but for others it represents a challenge to their inventiveness and insight. Nonetheless, you must plan, and sometimes things even go according to intention.

BACKGROUNDS

Deciding what part background must play in relation to foreground is a camera-positioning issue. If a character is depressed and hungry, there is a nice irony in showing that her bus stop is outside a McDonalds and that she is being watched by a huge Ronald McDonald. The composition will unobtrusively highlight her dilemma and suggest that she is tempted to blow her bus money on a large portion of french fries. Sometimes the subject is in the middle ground (a prisoner, bars in foreground, cellmate in background at back of cell, for instance). Foreground compositional elements are an important part of creating depth.

CAMERA AS INSTRUMENT OF REVELATION

Looking down on the subject, looking up at the subject, or looking at it through the treetrunks of a forest all suggest different contexts and different ways of seeing—and therefore of experiencing—the action central to the scene. The camera should be used as an active instrument of revelation. While you can manufacture this sense of revelation through Eisenstein's dialectical cutting, this may be just too intrusive a way to get your point across. More subtle and convincing is to build this multilevel consciousness into the shooting itself. Exploiting the location as a meaningful environment and being responsive to the actions and sightlines of participants in a scene can create a vivid and spontaneous sense of the scene's dynamics unfolding. Why? Because we are sharing the consciousness of someone intelligent and intuitive who picks up all the underlying tensions. Instead we often get the consciousness of someone who merely swivels after whatever moves or makes a noise, as dogs do.

SPEED COMPROMISES FOR THE CAMERA

When shooting action sequences, you may need to ask people to slow their movements because movement within a frame can look 20–30% faster than it does in life. Even the best camera operator cannot keep a profile in tight framing if the actor moves too fast. If the actor strays from the chalk line on the floor, the operator may lose focus. Such compromises on behalf of technology raise interesting questions about how much you should forego in the way of performance spontaneity to achieve a visually and choreographically polished result. Much will depend on the expertise of your actors and crew, but even the time of day you shoot may affect where you compromise because tired actors are more likely to feel they are being treated like glove puppets than fresh ones. Politics and expediency do not end here, for the crew can be disappointed or even resentful if you always forego interesting technical challenges on behalf of the cast.

WORK WITHIN YOUR MEANS

Any departure from the simple in cuts and camera movements must be motivated by the needs of the story if the audience is to feel they are sharing someone's consciousness. Good examples of subjectively motivated technique are Oliver's shock-cut view of the convict in the graveyard scene in Oliver Twist (1948) and dollying through the noise and confusion of a newsroom in All the President's Men (1976).

Such visual devices are dramatically justified, but dollying, craning, and other big-budget visual treatments are not strictly necessary for the low-budget filmmaker because few impressions cannot be achieved in simpler ways. Whole films have been successfully made with a static camera mainly at eye level or without cuts within a scene. Look at the opposite extreme: heavily scored music, rapid editing, and frenetic camera movement. These are mostly used as nervous stimulation to cover for a lack of content. Just roll around the channels on your TV and visit MTV.

Complex camera movement needs to be justified or it's gratuitous. In a film about dance like Emil Ardolino's Dirty Dancing (1987), Jeff Jur's camera cannot remain static on the sidelines. It must enter the lovers' dance and accompany them. Can this ever be done inexpensively? Yes. An experienced camera operator, using a wide-angle lens and taking advantage of a moving subject in the foreground that holds the eye, can handhold the camera and dispense with truckloads of shiny hardware. As mentioned, the Steadicam™ counterweighted body camera support can, in experienced hands, produce wonderfully fluid camerawork. See Mike Figgis' Leaving Las Vegas (1995) for good examples by DP Declan Quinn, who was first a documentary cameraman.

STUDY THE MASTERS

To know how best to shoot any particular scene, study the way good directors have shot situations analogous to yours. Learn from them, but do not be ruled by them. In Chapter 5, Project 5-2: Editing Analysis, there is a film study project to help you define a director's specific choices and intentions.