CHAPTER 38

PREPARING TO EDIT

Most of the operations described in this chapter are the editor's responsibility, but a director must know postproduction procedures to get the best film from the editing stage. Editing is not just assembly, as the Hitchcock mythology suggests, but more like coaxing a successful performance from an imperfect and incomplete composer's score. This operation requires you to see, listen, adapt, think, and imagine as you try to fulfill something to the best of its emerging potential.

POSTPRODUCTION PERSONNEL

The people who complete the postproduction of a film are the editor and his or her assistants, the composer, the sound editor, and the sound mix engineer.

THE EDITOR'S ROLE AND RESPONSIBILITIES

From the number and complexity of the postproduction processes below, it's evident how important the editor and editing assistants are, both technically and creatively. For this reason, and because editors deal with the structure and flow of narrative, being an editor is the most common professional path to directing.

DIPLOMACY

If the editing staff are not hired until after shooting, they receive the director when he or she may be in a state of considerable anxiety and uncertainty. For the film, though shot, has yet to prove itself. Many directors suffer a sort of postnatal depression in the trough following the sustained impetus of shooting, and most, however confident they may appear, are morbidly aware of their material's failures. If the editor and director do not know each other well, both will usually be formal and cautious. The editor is taking over the director's baby, and the director often carries mixed and potentially explosive emotions.

PERSONALITY

The good editor is patient, highly organized, willing to experiment endlessly, and diplomatic about trying to get his or her own way. Assistant editors mirror these qualities.

CREATIVE CONTRIBUTION

The editor's job goes far beyond the physical task of assembly, and the good editor—really someone of author caliber working from given materials—is highly aware of the material's possibilities. Directors are handicapped in this area by over-familiarity with their own intentions. The editor, not being present at shooting, comes on the scene with an unobligated and unprejudiced eye and is ideally placed to reveal to the director what possibilities or problems lie dormant within the material.

On a documentary or improvised fiction film, the editor is really the second director because the materials may be inherently entertaining, but they lack design and so are capable of broad possibilities of interpretation. The editor must often make responsible subjective judgments. Even in a tightly scripted fiction film, the editor needs the insight and confidence to know when to bend the original intentions to better serve the film's underlying needs. Editing is thus always far more than following a script, just as music is much more than playing notes in the right order. Composing is in fact the closest analogy to the editor's work, and many editors have music among their deepest interests.

DAILIES

Feature films normally employ the editor from the start of shooting, so the unit's output can be assembled as fast as it is shot. With low-budget films, however, economics may prevent cutting until everything is shot. This, as we have said, is risky because errors and omissions surface when it may be too late to rectify them. The editor should see dailies so that any necessary reshooting can be scheduled before quitting the location. Many 35 mm feature film cameras generate a video feed and enable a simultaneous video recording. This allows instant replay and mitigates the unit's absolute dependency on the script supervisor's powers of observation. The low-budget film shoot will probably have no such luxury, but if dailies can be synchronized at home base they can be transferred from the editing machine screen to videotape at minimal cost and seen at the location on a VCR.

PARTNERSHIP

Relationships between directors and editors vary greatly according to the chemistry of status and temperaments, but the director will initially discuss the intentions behind each scene and give any necessary special directions. The editor then sets to work making the assembly, which is a first raw version of the film. Wise directors leave the cutting room so they can return with a usefully fresh eye. The obsessive director sits in the cutting room night and day watching the editor's every action. Whether this is at all an amenable arrangement depends on the editor. Some enjoy debating their way through the cutting procedure, but most prefer being left alone to work out the film's initial problems in bouts of intense concentration over their logs and equipment.

In the end, very little escapes discussion; every shot and every cut is scrutinized, questioned, weighed, and balanced. The creative relationship is intense, and often draws in all the cutting room staff and the producer. The editor must often use delicate but sustained leverage against the irrational prejudices and fixations that occasionally close like a trap around the heart of virtually every director. Ralph Rosenblum's book When the Shooting Stops … the Cutting Begins (New York: Viking Press, 1979) demonstrates just how varied and even crazed editor/director relationships can be.

DIRECTOR-EDITORS

In low-budget movies, the director often becomes the editor under the rubric of economics. This is a false economy, with the real reason often being an unwillingness to share control under the mistaken belief that no unified artistic identity for the film will otherwise be possible. Such a person often has great difficulty absorbing criticism, seeing it as an attack on his or her right to individuality and autonomy. Editing your own work, unless it is a limited or exercise film, is always a mistake, particularly for the inexperienced. Even among famous feature directors, some of the slackest films come from people wearing too many hats. See Dances with Wolves (1990) at 183 minutes, then bear in mind that Kevin Costner—star, director, and producer—issued a director's cut of 224 minutes.

Every film is created for an audience, so every film needs the steadying and detached point of view of an editor as a proxy for the audience. A good mind in creative tension with the director is also an inestimable asset. Not only does it ensure against tumbling into the abyss of subjectivity, but it will advance alternatives and help to question every assumption. Lacking this partnership tension, the director never gets the necessary distance from the material, and falls prey to subjective familiarity with it. Either the director-editor cannot bear to cut anything, or the cuts will get shorter and shorter, and the movie will be intercut to the point where only the film's progenitor can still understand it. This is less an indulgent love relationship than a self-flagellating dislike in which the director-editor puts the film through contortions in the attempt to cure all its imagined deformities.

In truth, the scrutiny of the emerging work by an equal, the editor's advocacy of alternative views, and collaboration all on its own produce a tougher and better balanced film than any one person can generate alone. You are the exception? Please, please think again.

EDITING: FILM OR VIDEO?

With film and video nonlinear editing (NLE), any part of an edited version can be substituted, transposed, or adjusted for length. This was emphatically not so with earlier linear video editing systems, which some people may still have to use. In linear systems the edit is compiled by making a series of transfers from a source machine to a recorder. Subsequent work on the edited version is hampered because changing the length of a shot means either altering a following shot by the added or deleted amount or retransferring absolutely everything subsequent to the change. Using some workaround techniques, you can do perfectly sophisticated editing, but it is deathly slow and labor-intensive.

Nonlinear editing using NLE systems such as Adobe Premiere, Avid, Final Cut Pro, Lightworks, Media 100, or other software has become almost ubiquitous. From video original or film camera original material scanned by a telecine machine, the material is digitally recorded in the editing computer's hard drive. Edits are compiled as a series of clips arranged on a timeline. As in computerized word processing, you may enter at any point and transpose, lengthen, or contract what is there. With film editing you carry out a similar operation but use a splicer to cut and join the workprint and a synchronizer to keep picture and sound in synchronization. Using a table editing-machine such as a Steenbeck or Moviola, you are really using a motorized synchronizer with sound and viewing capability.

The early established Avid system (Figure 38-1) remains the front-runner in performance and user-friendliness but has been legendarily expensive to maintain. Avid has been losing ground among independents to the Apple computer company's Final Cut Pro (Figure 38-2), which is stable, modestly priced, and so flexible and capable that Avid has been forced to compete in the lower-end market. An advantage of Avid's low-end product is that the interface you learn is the same throughout Avid's range and will stand you in good stead if good fortune takes you up-market. If you want to buy the industry leader, be warned that Avid gained a reputation for arrogance toward smaller users and has a long history of frequent and costly upgrades. For Hollywood this is small potatoes, but small potatoes are usually the independent filmmaker's only potatoes.

Adobe Premiere and Final Cut Pro are both backed by large companies dedicated to serving large consumer markets, and their pricing and general

FIGURE 38-1

Avid Media Composer, the film industry's preferred editing software (photo courtesy of Avid).

reliability reflect a respect for the discriminating low-end user who wants professional features. There are a host of other NLE systems, but as always, when you contemplate uniting your destiny with equipment, look long and hard before you leap, and do so only after checking out a variety of comparable users' experiences via professional journals and user groups on the Internet.

A POSTPRODUCTION OVERVIEW

Postproduction is that phase of filmmaking when sound and picture dailies are transformed into the film seen by the audience. Supervised by the editor, both film and video postproduction include the following:

- For film or double-system video recording, synchronizing sound with action

- Screening dailies for the director's and producer's choices and comments

- Marking up the editing script strictly according to what was shot

- Logging material in preparation for editing

- Making a first assembly

- Making the rough cut

- Evolving the rough cut into a fine cut

- Supervising narration or looping (post-synchronized voice recording)

- Preparing for and supervising original music recording

- Finding, recording, and laying component parts of multi-track sound such as atmospheres, backgrounds, and sync effects

- Supervising mix-down of these tracks into one smooth final track

- Supervising shooting of titles and necessary graphics

- Supervising the film lab or video postproduction finalization processes

In film, the process subsequent to shooting also involves the following film laboratory processes:

1. Developing the camera original, and for larger-budget films, making a workprint to protect the negative from unnecessary further handling

2. Delivering to the cutting room either a film workprint or a tape for digitization made from a telecine scan of the negative

3. Once editing arrives at a fine cut and sound mix, the lab uses either the edited workprint or the edit decision list (EDL) to do the following:

a. Make film opticals (optical effects such as dissolves, fades, freeze frames, titling) that cannot be done during the final printing. This is an expen sive, highly specialized, and fallible process that nobody should under take lightly.

b. Conforming (or negative cutting), in which the original negative is cut to match the workprint so that fresh prints may be struck for release. Conforming includes instructing the printing machine to produce fades, superimpositions, and dissolves.

i. Conforming the traditional film-editing method is simply matching negative to workprint in a synchronizer.

ii. Matchback conforming follows a digitally edited film. An EDL of Key Code™ numbers compiled during digital editing is the sole guide to cutting the negative. This is risky business—see Digital Editing from Film Dailies section later in this chapter.

c. Making a sound optical negative from:

i. The sound magnetic master in the case of traditional mixing

ii. The sound program output in the case of a digitally edited film

d. Timing (or color grading) the picture negative by the lab in association with the director of photography (DP)

e. Combining sound negative with timed picture print to produce a com posite or “married” print to produce the first answer print (or trial print)

f. Making release prints after achieving a satisfactory answer print

g. Making dupe (duplicate) negatives via a fine grain interpositive process. For films with a large release, too many copies would subject the original negative to too much wear and tear, so dupe negs are made.

In nonlinear video postproduction, the camera original material has been digitized, stored in a computer hard drive, and assembled as segments laid along a timeline. Multiple sound tracks are laid and levels predetermined so you can listen to a layered and sophisticated track even while editing. Many systems are now so fast and have such large storage that you can edit on a laptop computer at full resolution. This abolishes the need for the two-pass offline and online processes with their extra time and expense. High definition video may force the use of editing at lo-res (low resolution) until it's once again cost-effective to use high-speed, high-capacity computing at the editing stage. This retrograde step will surely be only temporary. Depending on the features of the NLE system you use, postproduction will involve:

1. Digitizing a low-resolution, (inferior-grade) image so that much material can be stored in a hard drive of limited capacity

2. Finalizing sound in the audio-sweetening process using sophisticated sound processing software such as DigiDesign's ProTools. Beyond simple level setting, such programs enable:

a. Dynamics. Control over sound dynamics such as:

i. Limiting (sound dynamics remain linear until a pre-set ceiling, when they are held to that ceiling level).

ii. Compression (all sound dynamics are compressed into a narrower range but remain proportionate to each other)

b. Equalization control (sound frequency components within top, middle, and bottom of sound range can be individually adjusted, or preset pro grams applied)

c. Filtering. For speech with prominent sibilants, for instance, you can use a de-essing program.

d. Pitch changes or pitch bending. This betrays ProTools' musical roots, and it can be very useful for surreal sound effects or creating naturalistic variations from a single source.

e. Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) integration. This allows you to integrate a keyboard-operated sampler or music setup.

f. The EDL of the final edit is used to re-digitize only the selected material.

3. The edit is reassembled by the computer at high resolution (hi-res).

4. The hi-res version is output to tape and becomes the master copy for future duplication.

The facility of NLE for finding everything you want in a flash obviates the old necessity to search through out-takes and other material. Editors report that because they are no longer forced to contemplate unused material in their daily work, it is fatally easy to miss diamonds in the rough. Editing schedules have also gotten shorter, so the editor must fight these pressures and make sure nothing useful has been overlooked by the fine-cut stage.

Online Edit: If offline editing has produced a low-grade picture and an EDL, the production is ready for online editing. A computer-controlled rig uses the EDL to assemble a high-quality version of the film from re-digitized camera original cassettes. This process is the video equivalent of the film process's conforming or negative cutting. Producing a video final print includes:

- Timebase correction (electronic processing to ensure the resulting tape conforms to broadcasting standards)

- Color correction

- Audio sweetening as described previously

- Copy duplication for release prints

Two good sources of information at every level are Kodak's student program, reachable through www.kodak.com/go/student, and DV Magazine at www.dv.com for up-to-date information and reviews on everything for digital production and postproduction. Kodak has every reason to want people to continue using film and provides superb guidance in its publications and Web sites, which are prolific and as labyrinthine as you would expect from an organization with so many divisions.

SYNCING DAILIES

It is beyond the scope of this book to describe the procedure of film dailies syncing, other than to say that the picture marked at the point where the clapper board bar has just closed and the sound track marked at the clapper bar's impact are aligned in a synchronizer or table editor so that discrete takes can be cumulatively assembled for a sync viewing. Every respectable filmmaking manual covers this process (see this text's bibliography).

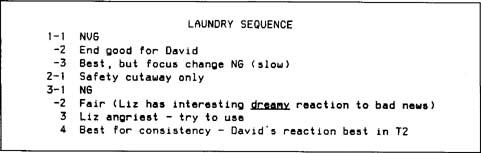

KEEPING A DAILIES BOOK

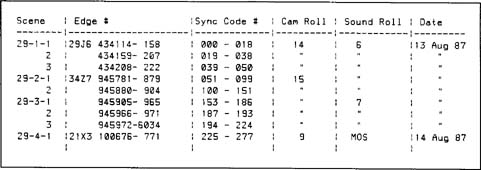

When assembling dailies for either a film or video viewing, make a dailies record book or use the NLE database. A simple old-fashioned book is a preparatory log of slate and take numbers in a sturdy notebook, divided by sequences and using one line per take. Take scene, slate, and take numbers from the camera log and leave columns for film edge numbers (or video timecode numbers) and blank space for cryptic notes during the dailies viewing. Figure 38-3 shows a completed section of the dailies book. An NLE program will outline its database functions in the manual, and this should allow you to display your material by different

FIGURE 38-3

Typical dailies book notes.

priorities such as ID number, date, description, and so on. Date is useful because sequences are usually shot contiguously.

CREW'S DAILIES VIEWING SESSION

At the completion of shooting, even though dailies have been viewed piecemeal, have the crew see all their work in its entirety. This lets everyone learn from their mistakes as well as from the successes that will make it to the final edit. Screening may have to be broken up into more than one session because 4 hours or so of unedited footage is about the longest even the most dedicated can maintain concentration. The editor may be present at this viewing, but discussion is likely to be a crew-centered postmortem rather than one useful to the editor.

EDITOR'S AND DIRECTOR's VIEWING SESSION

If by the end of shooting nothing has been cut, editor and director should see the dailies together. A marathon dailies viewing highlights the relativity of the material and the problems you face for the piece as a whole. You might discover that certain mannerisms are used repeatedly by one actor and must be cut around during editing if he or she is not to appear phony. Or you might discover that one of your two principals is often more interesting to watch and threatens to unbalance the film.

Next, view the material a scene at a time. With some labor, film dailies can be reassembled in scene order, and if dailies have been digitized, they can easily be called up in scene order. Run one sequence at a time and stop to discuss its problems and possibilities. The editor will need the dailies book (see previous discussion) to record the director's choices and note any special cutting information.

GUT FEELINGS MATTER

Note any unexpected mood or feeling. If, during the dailies viewing, you find yourself reacting to a particular character with, “She seems unusually sincere here,” write it down. Many gut feelings seem logically unfounded, and you are tempted to ignore or forget them. However, these are seldom isolated personal reactions and what triggered them is almost certainly embedded in the material for any first-time audience to experience.

Any spontaneous perceptions you note will be useful when inspiration lags later from over-familiarity with the material. If you fail to commit them to paper, they are likely to share the same fate as those important dreams that evaporate because you did not write them down.

TAKING NOTES

It is useful to have someone present who can take these dictated notes. If you write during a viewing, try never to let your attention leave the screen, as you can easily miss important moments and nuances. This means making large, scribbled notes on many pages of paper whenever you make notes yourself.

REACTIONS

When the crew or other people see dailies, there will probably be debates over the effectiveness, meaning, or importance of different aspects of the movie, and different crew members may have opposing feelings about the credibility and motivation of the characters. Listen rather than argue, for some of these reactions may be those of a future audience. Keep in mind that crew members are far from objective. They are disproportionately critical of their own discipline and may overvalue its positive or negative effect. They also have their own relationships with the actors and the filming situations.

THE ONLY FILM IS IN THE DAILIES

The sum of the dailies viewing is a notebook full of choices and observations (both the director's and those of the editor) and fragmentary impressions of the movie's potential and deficiencies. Absolutely nothing beyond what can be seen and felt from the dailies is any longer relevant to the film you are making. The script is a historic relic, like an old map to a rebuilt city. Stow it in the attic for your biographer. The film must be discovered in the dailies.

Now you confront the dailies; you change hats. You are no longer the instigator of the material, but with your editor you are a surrogate for the audience. Empty yourself of prior knowledge and intentions; your understanding and emotions must come wholly from the screen. Nobody in the cutting room wants to hear about what you intended or what you meant to produce. Keep it for your grandchildren.

SYNC CODING (FILM)

Film coding (also known as edge numbering or Dupont numbering) enables the editor to keep sound and picture in lip sync during the complicated operations involved in editing. It happens like this: After the dailies have been viewed (to ensure that they are indeed in sync), a film laboratory prints consecutive, yellow-ink numbers every foot or half-foot. Every new roll starts from where the last roll ended. Sync code numbers, printed in parallel on both sound and picture, function as unique, unambiguous sync marks, allowing original sync to be restored at any time. Recorded in a log, they also allow almost any length of anonymous-looking film to be reunited with its parent trims or off-cuts.

POOR MAN'S SYNC CODING (FILM)

Because edge coding is expensive, subsistence-level filmmakers handwrite numbers on the workprint dailies, sound and picture, every 3 feet or so. Use a 3-foot loop in the synchronizer as an interval guide.

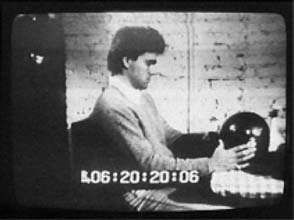

TIMECODING AND WINDOW DUB (LINEAR VIDEO)

When using linear videotape editing, you will need a timecoded camera original and a window-dubbed copy if you are to later use online (computerized)

|

Timecoded video frame. |

|

postproduction editing. Timecode means frame identification numbers generated at the time of recording and electronically interwoven with the video signal. Wherever possible, start each new cassette from a unique hour number, rather than always starting from zero, so that no two timecodes in your dailies are the same.

Next make a window dub or window burn-in. This is a copy cassette made from its original tape with the timecode displayed visually at the bottom of the frame in a window as cassette number, hours, minutes, seconds, and frames (Figure 38-4). Every frame in your production now has an individual identifying set of numbers, necessary for online editing.

DIGITAL EDITING FROM FILM DAILIES

It is almost universal to digitize film dailies and edit on NLE software. This requires that every negative image has its own timecode (called KeyCode™) because the resulting EDL will be used to conform, or match-edit, the camera original. There is no margin for error here; once the original is physically cut, there is no going back.

There is one tricky aspect. With a system that transfers 24 frames per second (fps) film to 30fps or 60 fields per second of video, you end up with four film frames being represented by five video frames. The process may be complicated by PAL and NTSC equipment that runs at different frame rates and film cameras that run at either 24 fps or 25 fps according to whether the material was generated for either American or other TV systems. If you edit on a phantom frame, it can only be approximated at the conforming stage. This means that if your sound track has been completely prepared in the digital mode, a succession of phantom frames over a succession of cuts may lead to cumulatively gaining or losing time. Put bluntly, your track may drift out of sync with the conformed film.

Make sure the person coordinating the process is thoroughly aware of the need for clarity about the ratio of film frames to video frames, known as pulldown mode in digitization, and knows definitively how to avoid unwanted consequences. There is a good description of all this in Thomas Ohanian's Digital Nonlinear Editing, 2nd ed. (Boston and London: Focal Press, 1998) in the chapter “The Film Transfer Process.” If you think it looks like video's resurrection of the “how many angels can dance on the point of a pin” debate, remember that ignoring the problem will be very, very costly.

LOGGING THE DAILIES

Because scenes will be shot, and therefore logged, out of order, it is a good idea to start each new sequence on a fresh page so the pages can eventually be re-filed in script order. If you type your log into a computer database, the computer will do the shuffle for you in a trice and print in scene order.

In film, every new camera start receives a new clapper-board number (see Chapter 32's Shot and Scene Identification section for a fuller explanation of different marking systems). The clapper exists so the editor can easily synchronize the separately recorded picture and sound. In the United States the board usually includes a script scene number, camera setup, and take numbers, while the European system often consists of just a consecutive setup and take number that must be reconciled with the shooting script or continuity sheets, if you have them.

In video, because picture and sound are usually recorded alongside each other on the same tape, no syncing up is necessary and a simpler marking system can be employed. Scene numbers (and clapper boards) are not even strictly necessary because videotape-editing methods do not permit working materials to be physically dismantled. While film beginnings and ends are defined by edge or KeyCode™ numbers, video is defined by timecode. Logging by timecode permits you to trace any piece of action back to its parent take.

The film-editing log may have to facilitate easy access to perhaps thousands of small rolls of film. The filing system and log format will depend on the editing equipment in use. If an upright Moviola—still the fearsome workhorse in the occasional cutting room—is used, the workprint will be broken down into individual takes and filed numerically in cans or drawers. If a table editor such as Steenbeck, Kem, or flatbed Moviola is used, the editor is more likely to withdraw selected sections from large rolls, each containing materials for a single scene. Even then, practice will depend on the work preferences of the editor. If large rolls are used, film logs may be organized like videocassette logs to reflect what is to be found cumulatively in that particular dailies roll.

Film, using separate sound and picture in the cutting room, requires that you log photographic edge numbers and the inked-on sync code numbers (or hand-applied sync code numbers) for the beginning and end of each take. Figure 38-5 is a typical film log entry for script scene 29. A log like this is a mine of useful information. We can see how many takes were attempted, how long (and therefore complete) each scene and each take were, where to find particular takes in camera original rolls if you need to make reprints, and even at what points the camera magazine was changed and which magazines were in use at the start of a new day.

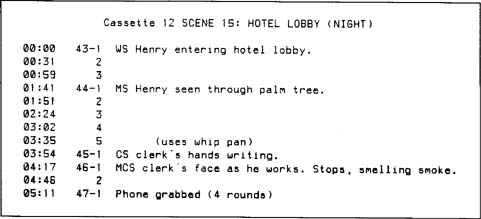

FIGURE 38-6

Typical videocassette log entries.

The video-editing log is a set of cumulative timecode numbers that allow the editor to quickly locate the right piece of action in a cassette that may hold from 20 to 120 minutes of action. It gives the starting point for each new scene and take. Descriptions should be brief and serve only to remind someone who knows the material what to expect. Note that the log (Figure 38-6) records function, not quality; there is no attempt to add the qualitative notes from the dailies book. To do so would overload the page and make it hard to use.

The figures at the left (see Figure 38-6) are minutes and seconds, but they might be cumulative numbers from the digital counter on your player deck. When materials are timecoded, log by the code displayed in the electronic window.

In the log examples there are a number of standard abbreviations for shot terminology that are listed in the glossary. Make a dividing line between sequences and give the sequence a heading in bold writing. Because the log exists to help quickly locate material, any divisions, indexes, or color codes you can devise to assist the eye in making selections will ultimately save time. This is especially true for a production with many hours of dailies.

MARKING UP THE SCRIPT

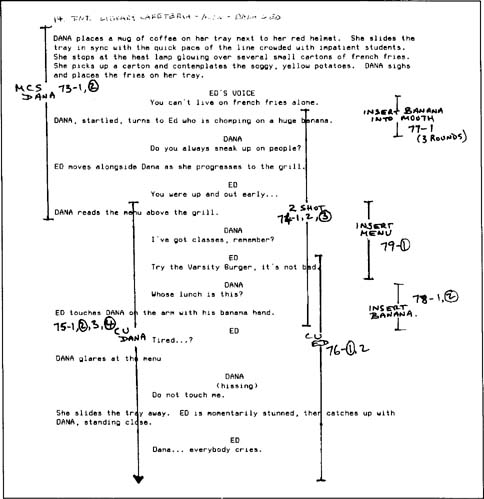

When logging is complete, the editor is ready to prepare the editor's script, each page of which should end up looking like Figure 38-7. Although the editor's markings appear to duplicate the shooting script (see Chapter 30, Figure 30-1), they are made in the peace of the cutting room and reflect actual footage and the

FIGURE 38-7

Editor's script marked up with dailies coverage.

chosen takes—footage that finally and definitively exists in the cutting room. At a glance the editor can see from the bracketing and notations what angles exist for every moment of the scene and which takes seem best. This greatly speeds up assessing alternative cover during the lengthy period of refining the cut. When you must problem-solve, having graphic representation like this rather than thickets of verbiage saves untold time and energy.

To mark up the script, view material for one scene looking at one camera setup at a time. Note that a change of lens is treated as a new setup, for although the camera may not have physically moved, the framing and composition will be different. Each setup is represented as a line bracketing what the angle covers. Shots that continue over the page end in an arrow to indicate that the shot continues on the next page. Leave a space in the line and neatly write in the scene number, all its printed takes (circling those chosen), and the briefest possible shot description. More detailed information can now be quickly found in the continuity reports or dailies book.