CHAPTER 45

PLANNING A CAREER

All careers in filmmaking are much sought after, so you should decide how ready you are to sink your fortunes and identity in a whole way of life. There is always a gamble, of course, when you start something. Will you like it? Will you be good enough? The only way to know this is to do it. The competition will be stiff, but even if finally you go from film school into Web design, theater, or radio, for instance, there isn't another liberal education like it. A preparation in film, depending on what you absorb, is an education in photography, light, electricity, drama, writing, narrative construction, design, sound, composition, acting, and organization. Your time won't be wasted, no matter what you end up doing.

PERSONALITY TYPES

The film industry, unlike engineering or real estate management, lacks a career ladder with predictable steps for promotion. It's a branch of show business, and how far you get and how long you take to get there depends on your ability, tenacity, and to a lesser degree on your luck. Sustaining a commitment to filmmaking may be impractical if your primary loyalties are to family, community, and material well-being because the industry is informally structured, unpredictable, and assumes initiative and a total commitment in the individual. Actors, dancers, and anyone in the arts who doesn't have a private income will face the same conditions.

OPPORTUNITIES

Film and video are now inseparable and should be regarded as one multifaceted industry. At the local end are Web site development, wedding videos, advertising, corporate and educational films, and up in the stratosphere are the national or international high-budget feature films. Indie shorts and features are somewhere in the impoverished middle. At the local level, the adroit and those with good connections can sometimes set their own terms and over time develop a comfortable income. In the upper-level industry where budgets are high, the stakes are high, too, and so the demand on the young entrant for reliability and appropriate behavior is roughly the same as working in mine clearance. Those who march to a different drummer can cost themselves and their supervisors their professional lives.

THE IMPORTANCE OF PASSION

A truism: People only become good at what they are passionate about. If you are passionate about the cinema, you may be equally passionate about making movies, even though it is hard, slow, and unglamorous work. Yes, unglamorous. If you really love it, you can make your way in that world. This, however, is true for anything at all, anywhere, that takes strong personal initiative. A lot of people go to film school to see whether they “have it” and whether they like production—and not all do.

How can you tell who has it? After decades of teaching in an open-admissions film school, my colleagues and I still cannot accurately predict who will thrive, although who won't is a lot more evident. Most film schools are strictly selective, and each faculty tends to believe the self-fulfilling prophecy that their selection methods work. If a film school rejects you, consider yourself in some good company and find another way to go forward—as Mike Figgis did, for example.

Below are descriptions of the three major personality types that tend to succeed in film school and the film industry. You should know the stakes before you decide to head to film school.

WHO SUCCEEDS IN FILM SCHOOLS AND THE FILM INDUSTRY

Filmmaking flies in the face of many romantic cultural beliefs. It is not glamorous and not an individualist's medium, for you can't be the isolated, suffering artist among a dozen or more hard-pressed collaborators. It is unsuitable for those who are undisciplined, unreliable, and non-perfectionist. Equally unsuitable are those whose egos, hostilities, and insecurities prevent them from working with (or especially under) other people. Film schools therefore receive people with many illusions culled from publicity and wishful thinking. Such students either adapt or let the dream go. But many people discover the impediments in themselves in film school and move successfully to change them, which is a large part of a film school's job.

There are places in the industry for three kinds of persons:

- The meticulous, committed craftsperson. This person gives his or her all to the work taken on and practices the highest standards in work, commitment, and diplomacy. Most find huge satisfaction in crafts other than directing. This is not a tragedy because most really grow to love what they do and find it very fulfilling.

- The craftsperson with an author inside struggling to get out. This person learns to become successful in his or her area—usually editing, cinematography, acting, and occasionally screenwriting—until someone influential recognizes that he or she has sufficient experience and a special authorial reach and is ready to direct.

- The craftsperson who is a fully realized visionary. This person is to film schools what Mozart was to music. He or she emerges from film school with a film that everyone recognizes as masterly.

Anyone lacking #1's discipline, commitment, and low ego is unsuited to the collaborative nature of filmmaking. This category is by far the most numerous, although most younger people in the industry think of themselves as #2 material. Only #3 directs straight out of film school, and the likelihood that you are naturally this kind of person is roughly equal to your chances of winning the lottery. Most progress, in film as in everything else, is won by hard work and application, not talent or brilliance. Sometimes this person takes a comet's path: a successful student film leading straight into a disastrous experience in the film industry. A productive director's first experience can prove fatal through a too-rapid promotion. Better to move slowly and carefully.

GETTING STARTED

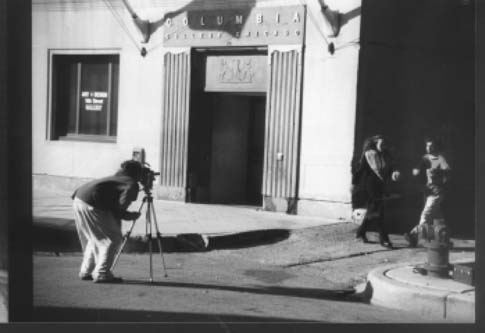

How to get started? Old timers used to scorn any form of schooling, but that has changed now that virtually every new film director is a film school alumnus (see Figure 45-1). A good school, of which there are now many, can cut years out of the learning curve, but even here there are drawbacks. Formal schooling is and must be geared to the common denominator; so it will be frustrating for those who learn slowly, rapidly, or who are more motivated than the average. In short, there are no sure routes, only intelligent traveling. If film school is out of the question, this book shows a way to prepare yourself outside the available educational structures. In any case, the best education will always be that you give yourself.

APPRENTICESHIP AS A BEGINNING

Older people in the film and TV industries may tell you that only on-the-job experience counts. Many of them received no college-level education and believe it fills young people's heads with idealistic dreams unrelated to the business. Because they tend to value procedural knowledge and professionalism (often deficiencies in recent graduates), they assume schooling fails.

Certainly school cannot teach the consistency, tact, and reliability that are the hallmarks of professionalism, nor should it drill students in industrial procedures at the expense of a conceptual education, which is the job of a college. Some students eagerly drop their schooling when an industry opening comes their way. It seems like a dream come true, but it is almost always a terrible mistake. They should know that their progress will be slow and their self-esteem eroded by the self-serving mystiques propagated by their seniors.

I am myself a scarred survivor of industry apprenticeship, so I want to stress the benefits of a purposeful education. During my teaching career I saw students in a 15-week editing class mastering techniques and using insights that took me 10 years on the job to invent for myself. That I learned slowly and in isolation isn't unusual: in the freelance world, know-how and experience are earning power, so workers systemically avoid enlightening their juniors. Most are not secure enough to share their knowledge, or they live highly pressured lives and consider it no part of their job to prepare “the kid” for more responsibility. You have to steal knowledge while serving as the company peon. How much easier it is when prior schooling has made you ready and eager to assume more complex duties as they arise.

WHAT FILM SCHOOL CAN DO

A good film/video education imparts:

- A broad cultural and intellectual perspective on your chosen medium

- The history from which your role grows

- The opportunity to relive that history by starting with simple and primal techniques

- Some marketable skills

- A lot of hands-on experience

- Experience of working as part of a team, sometimes in a senior and sometimes in a junior capacity

- A can-do attitude that isn't fazed by equipment and technical obstacles

- Aspirations to use your professional life for the widest good

- A community of peers with whom you will probably work for much of your life

By encouraging collaboration and unbridled individual vision, the educational process:

- Helps you determine early where your talents, skills, and energies truly lie

- Just as helpfully shows you where you do not belong

- Exposes you to a holistic experience of filmmaking, so you are not overawed by other people's knowledge and jobs

- Lets you learn through experiment and by overreaching yourself, something risky in the professional world until you are at the top of your craft

- Allows you to form realistic long-range ambitions

- Equips you to recognize appropriate opportunities when they arise, something the under-prepared worker is mortally afraid to do

Almost every entering film student wants to be a director. The true visionaries (they are very rare) direct all through film school and go straight into directing when they leave. Others of promise graduate with a useful technical skill and with the beginnings of an artistic identity. Most, on leaving school, will be neither ready nor wanting to direct for a number of years.

How do you find out which kind of person you are? Only by going through all the stages of making a film—no matter how badly. Here you will truly see the strengths and weaknesses of your own (and other people's) work. Film is such a dense and allusive language that a director must develop two separate kinds of skills, only one of which can be taught. The first is the slew of human and technical skills needed to put a well-conceived, well-composed series of shots on the screen and make them tell a story. The other is the skill of knowing yourself, of knowing what you can contribute to the world, and the capacity to remain true to yourself even when your work comes under attack. This has nothing to do with self-promotion and manipulating a gullible world into accepting your genius, as some people think.

The beginning filmmaker relives and reinvents the history of film and is surprised to discover how much about personal identity and perception he or she has taken for granted, and how meager and precarious this identity feels when placed in film form before an audience. This is the beginning of the humility and aspiration that fuels the artistic process. A good film school is the place to have this experience, for learning is structured and executed in the company of contemporaries. There should be enough technical facilities and enthusiastic expertise available. Here you can experiment and afford failures, whereas in the professional arena, unwise experiment is professional suicide.

In summary, film/video school is the place to:

- Learn crafts in a structured way that includes both theory and practice.

- Acquire an overview of the whole production process.

- Learn to use technical facilities.

- Learn professionalism (Be nice to people on your way up because you're going to meet them on your way down.).

- Learn how to use mentors and how to be one yourself.

- Experiment with roles, techniques, topics, and crafts.

- Put work before an audience.

- Become familiar with every aspect of your medium, including its history and aesthetics.

- Fly high on exhilarating philosophies of filmmaking and of living life.

- Continue to grow up (hard, lifelong work for us all).

- Develop a network of contacts, each tending to aid the others after graduation.

- Make the films that will show what you can do; you are what you put on the screen.

FINDING THE RIGHT SCHOOL

Many schools, colleges, and universities now have film courses. Although no serious study of film is ever wasted, be careful and critical before committing yourself to an extended course of study. Many film departments are under-equipped and under-budgeted. Sometimes film studies are an offshoot of the English department, perhaps originally created to bolster sagging enrollment. Avoid departments whose course structure shows a lack of commitment to field production. Film studies are necessary to a liberal education and for sharpening the perceptions, but divorced from film production, they become criticism, not creation. The measure of a film school is what the students and faculty produce. Quite simply, you must study with active filmmakers.

Be cautious about film departments in fine arts schools, especially if they undervalue a craftsperson's control of the medium and overvalue exotic form presented as personal vision. Fine art film students are sometimes encouraged to see themselves as reclusive soloists, like the painters and sculptors around them. This encourages gimmicky, egocentric production lacking the control over the medium that you can only get from a team. Graduates who leave school with no work under their arm find developing a career next to impossible.

At another extreme is the trade school, technically disciplined but infinitely less therapeutic. The atmosphere is commercial and industry-oriented, concerned with drilling students to carry out narrowly defined technical duties for a standardized industrial product. Union and Academy apprenticeship schemes tend to follow these lines; they are technically superb but often intellectually arid. They do lead to jobs, unlike the hastily assembled school of communications, which offers the illusion of a quick route to a TV station job. For every occupation there is always a diploma mill. In the TV version, expect to find a private, unaffiliated facility with a primitive studio where students are run through the rudiments of equipment operation. Needless to say, nobody but the much vaunted few ever find the career they hope for.

A good school balances sound technical education with a strong counterpart of conceptual, aesthetic, and historical coursework. In a large school like my own (Columbia College Chicago, see www.filmatcolumbia.com), a core of foundation courses leads to specialization tracks in screenwriting, camera, sound, editing, directing, producing, documentary, animation, and critical studies. Only a large school can offer a multiplicity of career tracks with a wide spectrum of types of filmmaking. My school has a unit located on a Hollywood studio lot so that our writers and producers can study with practitioners. Many go directly into internships, as you can find out from the Web site. Live action filmmakers sometimes feel as if they should also know about animation. To know it is an advantage, but it is an utterly separate discipline and closer to the graphic arts in its training.

There should be a respectable contingent of professional-level equipment as well as enough basic cameras and editing equipment to support the beginning levels. Students tend to rate schools by equipment, but this is shortsighted. More important is that a school be the center of an enthusiastic film-producing community, where students routinely support and crew for each other. The school's attitude toward students and how they fit into the film industry is the key. A school that rewards individualist stars or one isolated from working professionals can only partly prepare its student body for reality. A school too much in awe of Hollywood will probably promote pernicious ideas about success that destroy valuable potential. Be warned that some of the most reputable schools use a competitive system to decide whose work is produced. You may enter wanting to study directing but find your work doesn't get the votes and end up recording sound for a winner's project.

If the film school of your choice has been in existence for a while, successful former students may give visiting lectures and return as teachers. They often employ or give vital references to the most promising students. Through this networking process, the lines separating many schools from professional filmmaking are being crossed in both directions. The school filmmaking community tapers off into the young (and not so young) professional community to mutual advantage. In the reverse flow, mentors not only give advice and steer projects but exemplify the way of life the students are trying to make their own. Even in the largest cities, the film and video community operates like a village where personal recommendation is everything.

Although there is Garth Gardner's Gardner's Guide to Colleges for Multimedia and Animation, Third Edition (Fairfax, Virginia: Garth Gardner Publishing, 2002), there is nothing current that does the same for live action filmmaking. Some practical information, if you want to study film at graduate level, can be gained from Karin Kelly and Tom Edgar's Film School Confidential: The Insider's Guide to Film Schools (New York: Perigee, 1997), but currently it is 5 years out of date. Its opinions are formed on very small samples and should be taken with a pinch of salt. Kelly and Edgar have a Web site for Film School Confidential at www.lather.com/fsc/ where you can find comments, updates, and other information. There is no substitute for doing your own research, for which the Internet is now quite helpful. The main thing is to make comparisons and decide on a department's emphasis. A rousing statement of philosophy may be undercut when you scan equipment holdings and the program structure. Sometimes a department has evolved under the chairmanship of a journalist or radio specialist, so film and television production may be public relations orphans within an all-purpose communications department.

You can do a top-down study by reading Nicholas Jarecki's Breaking In: How 20 Movie Directors Got Their First Start (New York: Broadway Books, 2001), which contains interviews with directors on how they broke into the business. This is valuable for the reiteration of common values that go with making a film career, but it won't show you where the rungs of the ladder are. The fact is that you make them for yourself. The first attribute of a director is the ability to research a situation and to put together a picture from multiple sources of information. As you decide whether a particular film school fulfills your expectations, here are some considerations:

- How extensive is the department and what does its structure reveal?

Number of courses? (More is better)

Number of students? (More may not be better, but does enable variety of courses)

Subjects taught by senior and most influential faculty?

Average class size?

Ratio of full-time to part-time faculty?

- How long is the program? (see model syllabus; less than 2 years is suspiciously short)

- How much specialization is possible, and do upper-level courses approach a professional level or specialization?

- How much equipment is there, what kind, and who gets to use it? (This is a real giveaway)

- How wide is the introduction to different technologies?

At what level and by whom is film used?

Has the school adapted to digital video? (Faculties are sometimes dominated by film diehards)

How evenhanded is the use of technologies?

- What kind of backgrounds do the faculty members have?

What have they produced?

Are they still producing or do they rest on past laurels?

- How experienced are those teaching beginning classes? (Many schools have to use their graduate students.)

- Consider tuition and class fees:

How much equipment and materials are supplied?

How much is the student expected to supply along the way?

Does the school have competitive funds or scholarships to assist in production costs?

Who owns the copyright to student work? (Many schools retain their students' copyrights)

- What proportion of those wanting to direct actually do so? (Some schools make students compete for top artistic roles and sideline the losers)

- What does the department say about its attitudes and philosophy?

- What does the place feel like? (Try to visit the facilities)

- How do the students regard the place? (Speak to senior students)

- How much are your particular interests treated as a specialty?

- What kind of graduate program do they offer?

If you have a BA, an MFA is a good qualification for production and teaching.

A Ph.D. signifies a scholarly emphasis that generally precludes production.

- If the degree conferred is a BA or BFA, how many hours of general studies are you expected to complete, and how germane are they to your focus in film or video?

The very best way to locate good teaching is to attend student film festivals and note where the best films are being made. A sure sign of energetic and productive teaching, even in a small facility, is when student work is receiving recognition in competitions.

Some of the larger and well-recognized film/video schools in the United States are listed in the next chapter. Also listed are the major film schools around the world because many of this book's users will live in other parts of the globe. Most of these schools only take advanced or specially qualified students. A hard-to-get-into, expensive school is not necessarily a good school or the one that fits your profile. An inexpensive school that is easier to get into at the undergraduate level (like mine) may, in fact, fit you and your purse very well.

Americans sometimes assume that work and study abroad is easily arranged and will be an extension of conditions in the United States. Be warned that most foreign film schools, especially national film schools, have very competitive entry requirements, and that self-support through part-time work in foreign countries is usually illegal. As in the United States, immigration policies exclude foreign workers when natives are underemployed. That situation changes only when you have special, unusual, and accredited skills to offer. Check local conditions with the school's admissions officer and with the country's consulate before committing yourself. Also check the length of the visa granted and the average time it takes students to graduate—sometimes these durations are incompatible.

SELF-HELP AS A REALISTIC ALTERNATIVE

Perhaps you can afford neither the time nor money to go to school and must find other means to acquire the necessary knowledge and experience. Werner Herzog has said that anyone wanting to make films should waste no more than a week learning film techniques. Even with his flair for overstatement this period would appear a little short, but fundamentally I share his attitude. Film and video is a practical subject and can be tackled by a group of motivated do-it-yourselfers. This book is intended to encourage such people to learn from making films, to learn through doing, and, if absolutely necessary, through doing in relative isolation.

Self-education in the arts, however, is different from self-education in a technology because the arts are not finite and calculable. They are based on shared tastes and perceptions that at an early stage call for the criticism and participation of others. Even painters, novelists, poets, photographers, or animators—artists who normally create alone—are incomplete until they engage with society and experience its reaction. Nowhere is public acceptance more important than with film, the preeminent audience medium.

PROS AND CONS OF COLLABORATION

If you use this book to begin active filmmaking or videomaking, you will recognize that filmmaking is a social art, one stillborn without a keen spirit of collaboration. You will need other people as technicians and artistic collaborators if you are to do any sophisticated shooting, and you will need to earn the interest of other people in your end product. If you are unused to working collaboratively—and sadly, conventional education teaches students to compete for honors instead of gaining them cooperatively—you have an inspirational experience ahead. Filmmaking is an intense, shared experience that leaves few aspects of relationship untouched. Lifelong friendships and partnerships develop out of it, but not without flaws emerging in your own and other people's characters as the pressure mounts. With determination you can change your habits, and many people do.

Somewhere along the way you will need a mentor, someone to give knowledgeable and objective criticism of your work and to help solve the problems that arise. Do not worry if none is in the offing right now, for the beginner has far to go. It is a law of nature in any case that you find the right people when you truly need them.

PLANNING A CAREER TRACK DURING YOUR EDUCATION

Whether you are self-educated or whether you pursue a formal education at school, the way people receive your finished work will confirm which filmmaker category is yours and whether you are a visionary and can realistically try to enter the industry as a director. Chances are you belong with the vast majority for whom directing professionally is still very far off. In this case you must develop a craft specialty to make yourself marketable and gain a foothold in the industry. This is the subject of Chapter 47: Breaking into the Industry.