3 |

The Influence of the Documentary |

||

D. W. Griffith and his contemporaries were part of a growing commercial industry whose prime goal was to entertain. This meant that the ideas presented in their films were subordinate to their entertainment value. Griffith attempted to present conceptual material about society in Intolerance and failed. Although other filmmakers—such as King Vidor (The Crowd, 1928), Charlie Chaplin (The Gold Rush, 1925), and F. W. Murnau (Sunrise, 1927)—blended ideas and entertainment values more successfully, the commercial film has more often been associated primarily with entertainment.

The documentary film, on the other hand, has always been associated with the communication of ideas first and with entertainment values a distant second. Griffith was very successful in using editing techniques to involve and entertain. He was less successful in developing editing techniques that would help communicate ideas. Which editing theories and techniques facilitate the communication of ideas? How do ideas work with the emotional power implicit in editing techniques?

Because the documentary film was less influenced by market forces than commercial film was and because the filmmakers attracted to the documentary had different goals from commercial filmmakers, often goals with social or political agendas, the techniques they used often displayed a power not seen in the commercial film. Subsidized by government, these filmmakers blended artistic experimentation with political commitment, and their innovations in the documentary broadened the repertoire of editing choices for all filmmakers.

The documentary, or “film of actuality,” had been important from the time of the Lumière brothers in France, but it was not until the 1920s that the work of the Russian filmmakers—Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and the National Film School under Kuleshov—and the release of Robert Flaherty's Nanook of the North (1922) prompted John Grierson in England to consider films of actuality and “purposive filmmaking.”1 As Paul Swann suggests, “Grierson was prompt to note Lenin's belief in ‘the power of film for ideological propaganda.’ Grierson's great innovation was to adapt this revolutionary dictum to the purpose of social democracy.”2

Grierson was very affected by the power of the editing in Potemkin and the method Eisenstein used to form, present, and argue about ideas visually (intellectual montage). There is little question that a dialectic between form and content became a working principle as Grierson produced his own film, The Drifters (1929), and moved on to produce the work of many others at the British Marketing Board.

Grierson took the principle of social or political purpose and joined it with a visual aesthetic. Greatly aided by the coming of sound after 1930, the documentary as propaganda developed into an instrument of social policy in England, in Germany, and temporarily in the United States. In their work, the filmmakers applied editing solutions to complex ideas. Through their work, the options for editing broadened almost exponentially.

IDEAS ABOUT SOCIETY

IDEAS ABOUT SOCIETY

The coming of sound was closely followed by shattering world events. In October 1929, the U.S. stock market crash signaled the onset of the Great Depression. Political instability led to the rise of Fascist governments in Italy and Germany. The aftereffects of World War I undermined British and French society. The United States maintained an isolationist position. The period, then, was unpredictable and unstable. The documentary films of this time searched for a stability and strength not present in the real world. The efforts of these filmmakers to find positive reinterpretations of society were the earliest efforts to communicate particular ideas about their respective societies. Grierson was interested in using film to bring society together. Working during the Depression, a fracturing event, he and others wanted to use film to heal society. In this sense he was an early propagandist.

ROBERT FLAHERTY AND MAN OF ARAN

Robert Flaherty's Man of Aran (1934) closely resembles a commercial film. In this fictionalized story of the Aran Islands off the coast of Ireland, Flaherty used actual islanders in the film, but he created the plot according to his goals rather than basing it on the lives of the islanders.

Man of Aran tells the story of a family that lives in a setting where they are dwarfed by nature and challenged by the land and sea. Flaherty used two shark hunts to suggest the bravery of the islanders, and the storm at the end of the film illustrates that their struggle against nature makes them stronger, worthy adversaries in the hierarchy of natural beings. People, not being supreme in the natural hierarchy, are shown to be worthy adversaries for nature when the challenge is considerable. In essence, a poetic interpretation of people's struggle with nature makes them look good.

This idea of the nobility of humanity and of its will to live despite the elements was Flaherty's creation. The Aran Islanders didn't live as he presented them. For example, the sharks they hunted are basking sharks, a species that is harmless to humans (the film implies that they are maneaters). Of course, Flaherty's production of such a film in 1934 in the midst of the Great Depression suggests how far he roamed from the issues of the day. Like Griffith, he had a particular mythic vision of life, and he re-created that vision in all of his films.

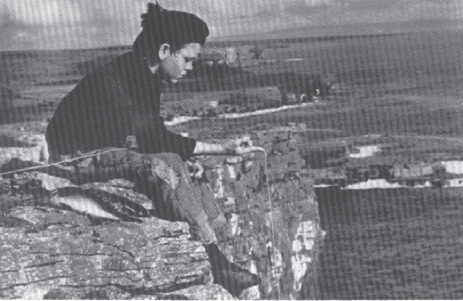

In terms of its editing, Man of Aran is similar to the early sound films of Mamoulian and Hitchcock. Music and simple sound effects are used as sound coverage for essentially silent sequences. There is no narrative, and where dialogue is used, it is equivalent to another sound effect. The actual dialogue is not necessary to the progress of the story. The film has a very powerful visual character, which is presented in a very formal manner. Although the film offers opportunity for dialectical editing, particularly in the shark hunts, the actual editing is deliberate and avoids developing a strong identification with the characters. In this sense, the intimacy so vital to the success of a film like Broken Blossoms is of no interest to Flaherty (Figures 3.1 to 3.4). Instead, Flaherty tries to create an archetypal struggle of humanity against nature, and dialectics seem inappropriate to Flaherty's vision. Consequently, the editing is secondary to the cumulative, steady development of Flaherty's personal ideas about the struggle. The fact that the film was made in the midst of the Depression adds a level of irony. It makes Man of Aran timeless; this quality was a source of criticism toward the film at the time.

Figure 3.1 |

Man of Aran, 1934. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 3.2 |

Man of Aran, 1934. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 3.3 |

Man of Aran, 1934. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 3.4 |

Man of Aran, 1934. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

For our purposes, however, Man of Aran presents the documentary film in a form similar to the commercial film. Performance, pictorial style, and editing serve a narrative: in this case, Flaherty's version of the life of the Aran Islanders. It is not purposive filmmaking, as Grierson proposed, but nor is it the Hollywood film he so vehemently criticized.

BASIL WRIGHT AND NIGHT MAIL

Night Mail (1936), produced by John Grierson and the General Post Office film unit and directed by Basil Wright, was certainly purposive, and it used sound particularly to create the message of the film. The film itself is a simple story of the delivery of the mail by train from London to Glasgow, but it is also about the commitment and harmony of the postal workers. If the film has a simple message, it's the importance of the job of delivering the mail. The sense of harmony among the workers is secondary.

Turning again to the events of the day, 1936 was a dreadful time in terms of employment. Political and economic will were not enough to overcome the international protectionism and the strains of the British Empire. Consequently, Night Mail is not an accurate reflection of feeling among postal workers. It is the Grierson vision of what life among the postal workers should be.

For us, the film's importance is the blend of image and sound and how the sound edit is used to create the sense of importance and harmony. As in all of these films, there is a visual aesthetic that is in itself powerful (Figures 3.5 and 3.6), but it is the sound work of composer Benjamin Britten, poet W. H. Auden (who wrote the narration), and above all Alberto Cavalcanti (who designed the sound) that affects the purposeful message Grierson intended.

The sound of the train simulating a cry or the rhythm of the narration trying to simulate the urgent, energetic wheels of the train rushing to reach Glasgow create a power beyond the images themselves. The reading, although artificial in its nonrealism, acts as Dovzhenko's visuals did—to create a poetic idea that is transcendent. The idea is reinforced by the music and by the shuffling cadence of the narration. Together, all of the sound, music, words, and effects elevate the images to achieve the unifying idea that this train is carrying messages from one part of the nation to another, that commerce and personal well-being depend on the delivery of those messages, and that those who carry those messages, the workers, are critical to the well-being of the nation. This idea, then, is the essence of the film, and it is the editing of the sound that creates the dimensions of the idea.

Figure 3.5 |

Night Mail, 1936. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 3.6 |

Night Mail, 1936. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

PARE LORENTZ AND THE PLOW THAT BROKE THE PLAINS

A more critical view of society was taken by Pare Lorentz in The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936), a film sponsored by the Resettlement Administration of the U.S. government. Lorentz looked at the impact of the Depression on the agricultural sector. The land and the people both suffered from natural as well as human-made disasters. The purposive message of the film is that government must become actively involved in recovery programs to manage these natural resources. Only through government intervention can this sort of suffering be alleviated.

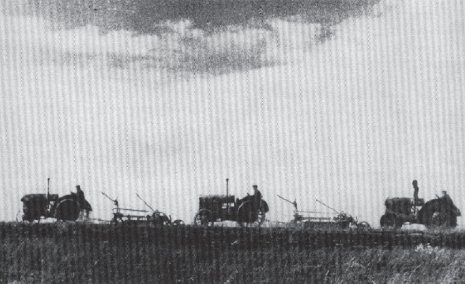

To give his message impact, Lorentz relied on the photojournalist imagery made famous by Walker Evans and others during the Depression. In terms of the visual editing, the film is imitative of Eisenstein, but the sequences aren't staged as thoroughly as Eisenstein's were. Consequently, the sequences as a whole don't have the power of Eisenstein's films. They resemble more closely the work of Dovzhenko in which the individual shots have a power of their own (Figures 3.7 and 3.8).

It is the narration and the music by Virgil Thomson that pull the ideas together. Lorentz has to rely on direct statement to present the solution to the government. In this sense, his work is not as mature propaganda as the later work of Frank Capra or the earlier work of Leni Riefenstahi. Lorentz was more successful in his second film, The River (1937). As Richard Meran Barsam states about Lorentz, “While (his films) conform to the documentary problem–solution structure, these films rely on varying combinations of repetition, rhythm, and parallel structure, so that problems presented in the first part of the films are solved in the second part, but solved through such an artistic juxtaposition of image, sound, and motif that their unity and coherence of development set them distinctly apart.”3

Figure 3.7 |

The Plow That Broke the Plains, 1936. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 3.8 |

The Plow That Broke the Plains, 1936. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

IDEAS ABOUT ART AND CULTURE

IDEAS ABOUT ART AND CULTURE

Flaherty, Grierson, and Lorentz had specific views about society that helped shape their editing choices. Other filmmakers, although they also held particular political views, attempted to deal with more general and more elusive ideas. How they achieved that aesthetic goal is of interest to us.

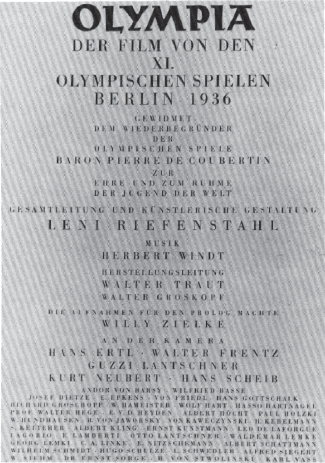

LENI RIEFENSTAHL AND OLYMPIA

It would be simple to dismiss Leni Riefenstahl's work as Nazi propaganda (Figure 3.9). Although Riefenstahl's Olympia Parts I and II (1938) are films of the 1936 Olympics held in Berlin and hosted by Adolph Hitler's Nazi government, Riefenstahl's film attempts to create a sensibility about the human form that transcends national boundaries. Using 50 camera operators and the latest lenses, Riefenstahl had at her disposal slow-motion images, microimages, and images of staggering scale. She presented footage of many of the competitions in the expected form—the competitors, the competition, the winners—but she also included numerous sequences about the training and the camaraderie of the athletes. Part II opens with an idyllic early morning run and the sauna that follows the training. Riefenstahi used no narration, only music, and she didn't focus on any individual. She focused only on the beauty of nature, including the athletes and their joy.

This principle is raised to its height in the famous diving sequence near the end of Part II. This 5-minute sequence begins with shots of the audience responding to a dive and shots of competitors from specific countries. Then Riefenstahl cuts to the mechanics of the dive. Gradually, the audience is no longer shown. Now we see one diver after another. She concentrates on the grace of the dive, then she begins to use slow motion and shows only the form and completion of the dive. The shots become increasingly abstract. We no longer know who is diving. She begins to follow in rapid succession dives from differing perspectives. The images are disorienting. She begins to fragment the dives. We see only the beginning of dives in rapid succession. Then the dives are in silhouette, and they seem like abstract forms rather than humans. Two forms replace one. She cuts from one direction to another, one abstract form to another. Are they diving into water or jumping into the air? The images become increasingly abstract, and eventually, we see only sky.

Figure 3.9 |

Olympia, 1938. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

In 5 minutes, Riefenstahl has taken us from a realistic document of an Olympic dive (complete with an audience) to an abstract form leaping through space—graceful beauty in motion. Through the sequence, we hear only music and the splash of water as the diver hits the surface. Riefenstahl's ideas about beauty and art are brilliantly communicated in this sequence. No narration was necessary to explain the idea. Editing and music were the tools on which Riefenstahi relied.

W. S. VAN DYKE AND THE CITY

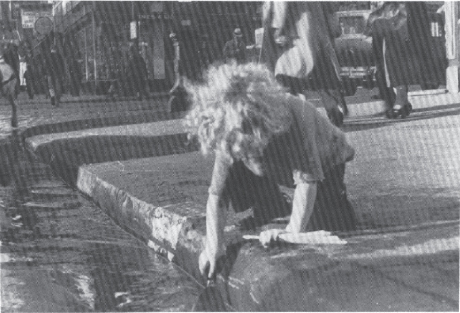

In the late 1930s, the American Institute of Planners commissioned a film about the future city to be shown at the 1939 World's Fair in New York City. W. S. Van Dyke and Ralph Steiner, working from a script by Henwar Rodakiewicz and Lewis Mumford (and an outline by Pare Lorentz), fashioned a story about the future that arises out of the past and present. The urgency of the new city is born out of contemporary problems of urban life. The images of those problems are in sharp contrast to the orderly prosperous character of the future city (Figures 3.10 to 3.12).

In The City (1939), ideas about politics are mixed with ideas about the culture of the city: urban life as a source of power as well as oppression. Unfortunately, the images of oppression are so memorable and so human that they overwhelm the suburban utopia presented later.

In the third section of the film, featuring the city of New York, Van Dyke and Steiner portray the travails of the lunch hour in the big city. Everyone is on the run with the inevitable congestion and indigestion. All this is portrayed in the editing; the pace and the music capture the charm and the harm of lunch on the run. This metaphor is carried through to the conclusion through images of the icons of the large city—the signs that, instead of giving the city balance, imply a rather conclusive improbability about one's future in the city of the present. This sequence prepares us for the city of the future.

As in The Plow That Broke the Plains, the American documentary structure follows a point–counterpoint flow that is akin to making a case for the position put forward in the concluding sequence, in this case, the city of the future. The film unfolds as a case for the prosecution would in a trial. It's a dramatic device differing from the slow unfolding of many documentaries. As in the Lorentz film, music is very important. Another similarity is the strength of the individual shots. Van Dyke and Steiner, as still photographers, bring a power to the individual images that undermines the strength of the sequences. However, the film does succeed in creating a sense that the city is important as more than an economic center. The urban center becomes, in this film, a place to live, to work, and to affiliate and a cultural force that can shape or undermine the lives of all who live there. Van Dyke's city becomes more than a place to live. It becomes the architectural plan for our quality of life.

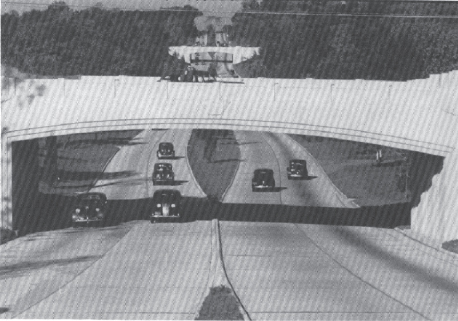

Figure 3.10 |

The City, 1939. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

Figure 3.11 |

The City, 1939. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

Figure 3.12 |

The City, 1939. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

IDEAS ABOUT WAR AND SOCIETY

IDEAS ABOUT WAR AND SOCIETY

The shaping of ideas became even more urgent when the purpose of the film was to help win a war fought for the continued existence of the country. Grierson provided the philosophy for the propaganda film, and Eisenstein and Pudovkin provided the practical tools to shape and sharpen an idea through editing. In the 1930s, such filmmakers as Riefenstahi put the philosophy and techniques to the practical test. Her film, Triumph of the Will (1935), became the standard against which British and American war documentaries were measured. The work of Frank Capra, William Wyler, and John Huston in the United States and of Alberto Cavalcanti, Harry Watt, and Humphrey Jennings in Great Britain displayed a mix of personal creativity and national purpose. Their films drew on national traditions, and in their own way, each advanced the role of editing in shaping ideas effectively. Consequently, the power of the medium seemed to be without limit and thus dangerous. This perception shaped both the fascination with and the suspicion of the media, particularly film and television, in the post-war period.

FRANK CAPRA AND WHY WE FIGHT (1943–1945)

Frank Capra, one of Hollywood's most successful directors, was commissioned by then-Chief of Staff George C. Marshall to produce a series of films to prepare soldiers inducted into the army for going to war. The Why We Fight series (1943–1945), seven films produced to be shown to the troops, are among the most successful propaganda films ever made. As Richard Dyer MacCann suggests about the films, “They attempted (1) to destroy faith in isolation, (2) to build up a sense of the strength and at the same time the stupidity of the enemy, and (3) to emphasize the bravery and achievements of America's allies. Their style was a combination of a sermon, a betweenhalves pep talk, and a barroom bull session.”4

Capra used compilation footage, excerpts from Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will, re-created footage, and excerpts from Hollywood films to create a sense of actuality and credibility. To make dramatic points, Capra resorted to animation. Maps and visual analogies—such as the juxtaposition of two globes, a white earth (the Allies) and a black earth (the Axis), in Prelude to War (1942)—illustrate the struggle for primacy. Capra used the animation to make a dramatic point with simple pictures.

The narration is colloquial, highly personalized, and passionate about characterizing each side in terms of good and evil. The narration features slang, rather than objective language. Read by Walter Huston, it illustrates and deepens the impact of the images.

Picture and sound complement one another, and where possible, repetition follows a point made in a rapid visual montage. The pace of the film is urgent. Whether the scene has to do with the subversion necessary from within in the takeover of Norway or the more complex portrayal of French capitulation and Nazi perfidy and consequent glee (the repetitive shot of Hermann Göring rubbing his hands together), Capra highlighted victim and victimizer in the most dramatic terms (Figures 3.13 to 3.15).

Capra, then, used visual and sound editing in a highly dramatized way. A great deal of information is synthesized into an “us against them” structure. Eisenstein's dialectic ideas have rarely been used more effectively.

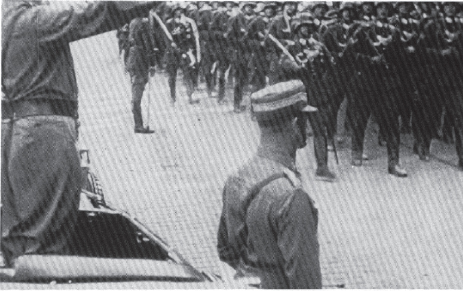

Figure 3.13 |

Divide and Conquer, 1945. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

Figure 3.14 |

Divide and Conquer, 1945. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

Figure 3.15 |

Divide and Conquer, 1945. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

HUMPHREY JENNINGS AND DIARY FOR TIMOTHY

By the time he produced Diary for Timothy (1945), Humphrey Jennings had already directed two of the greatest war documentaries, Listen to Britain (1942) and Fires Were Started (1943). Whereas Capra in his films concentrated on the combatants and the war, Jennings, in his work, concentrated on the home front.

Diary for Timothy is a film about a baby, Timothy, born in 1944. The film speculates about what kind of world Timothy will grow up in. The film's tone is anxious about the future. As with all of Jennings's work, this film tends to roam visually, not focusing on a single event, place, or person. To create a sense of the society as a whole, Jennings includes many people at work or at home with their families. This general approach poses the problem of how to unify the footage (Figure 3.16).

Figure 3.16 |

Diary for Timothy, 1945. Stills provided by British Film Institute. |

In this film, the baby, at different ages, acts as a visual reference point, and the narration addressed to Timothy (read by Michael Redgrave, written by E. M. Forster) personalizes and attempts to shape a series of ideas rather than a plot.

The film contains six sections. Although there is a temporal relationship, there is no clear developmental character. Instead of a story, as Alan Lovell and Jim Hillier suggest, “A Diary for Timothy depends for its effect on highly formal organization and associative montage.”5 Within the montage sections, the sum is greater than the parts. Again quoting from Lovell and Hillier:

With the wet reflection of a pit-head and “rain, too much rain,” the film launches into a further sequence of images and events: Tim's mother writing Christmas cards, rain on Bill's engine, rain in the fields, Tim's baptism, Peter learning to walk again, Goronwy brought up from the pit on a stretcher. It is of course possible to attempt an intellectual analysis of the sequence of images but such analysis rarely takes us far enough. Jennings seems to have reached such a pitch of personal freedom in his association of ideas and shifts of mood that we lose the precise significance of the movement of the film and respond almost completely emotionally.6

This emotion is charged with speculation in the last sequence. Instead of a hopeful, powerful conclusion, as in Listen to Britain, or a somber, heroic conclusion, as in Fires Were Started, Jennings opted for an open-ended challenge. He put the challenge forward in the narration:

Well, dear Tim, that's what's been happening around you during your first six months. And, you see, it's only chance that you're safe and sound. Up to now, we've done the talking; but, before long you'll sit up and take notice.-.-.-.-What are you going to say about it and what are you going to do? You heard what Germany was thinking, unemployment after the war and then another war and then more unemployment. Will it be like that again? Are you going to have greed for money or power ousting decency from the world as they have in the past? Or are you going to make the world a different place—you and all the other babies?7

CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

Perhaps more than any other genre, the documentary has been successful in communicating ideas. The interplay of image and sound by filmmakers such as Riefenstahl, Capra, and Jennings has been remarkably effective and has greatly enhanced the filmmaker's repertoire of editing choices. These devices have found their way back into the fictional film, as evidenced in the work of neorealist filmmakers and the early American television directors whose feature film work has been marked by a pronounced documentary influence.