7 |

New Technologies |

||

The 1950s brought many changes to film. On the economic front, the Consent decrees of 1947 (antitrust legislation that led to the studios divesting themselves of the theatres they owned) and the developing threat of television suggested that innovation, or at least novelty, might help recapture the market for film. As was the case with the coming of sound in the late 1920s, new innovations had considerable impact on how films were edited, and the results tended to be conservative initially and innovative later.

This chapter concentrates on two innovations, each of which had a different impact on film. The first was the attraction to the wide screen, including the 35-mm innovations of Cinerama, CinemaScope, Vistavision, and Panavision and the 70-mm innovations of TODD-AO, Technirama, Supertechnirama, MGM 65, and, later, Imax. Around the world, countries adopted similar anamorphic approaches, including Folioscope. If the goal of CinemaScope and the larger versions was to increase the spectacle of the film experience, the second innovation, cinema verité, with its special lighting and unobtrusive style, had the opposite intention: to make the film experience seem more real and more intimate, with all of the implications that this approach suggested.

Both innovations were technology-based, both had a specific goal in mind for the audience, and both had implications for editing.

THE WIDE SCREEN

THE WIDE SCREEN

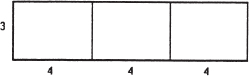

To give some perspective to the wide screen, it is important to realize that before 1950 films were presented in Academy aspect ratio; that is, the width-to-height ratio of the viewing screen was 1-:-1.33 (Figure 7.1).

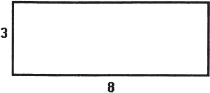

This ratio was replicated in the aperture plate for cameras as well as projectors. There were exceptions. As early as 1927, Abel Gance used a triptych approach, filming particular sequences in his Napoleon (1927) with three cameras and later projecting the images simultaneously. The result was quite spectacular (Figure 7.2).

In these sequences, the aspect ratio became 1-:-3. The impact of editing in these sequences was startling. How did one use a close-up? What happened when the camera moved? Was a cut from movement to movement so jarring or awkward that the strength of these editing conventions became muted? The difficulties of Gance's experiment didn't pose a challenge for film-makers because his triptych technique did not come into wide use. Other filmmakers continued to experiment with screen shape. Eisenstein advocated a square screen, and Claude Autant-Lara's Pour Construire un Feu (1928) introduced a wider screen in 1928 (the forerunner of CinemaScope). The invention of CinemaScope itself took place in 1929. Dr. Henri Chretien developed the anamorphic lens, which was later purchased by 20th Century–Fox.

Figure 7.1 |

Academy aspect ratio. |

Figure 7.2 |

Triptych format. |

It was not until the need for innovation became economically necessary that a procession of gimmicks, including 3-D, captured the public's attention. The first wide-screen innovation of the period was Cinerama. This technique was essentially a repeat of Gance's idea: three cameras record simultaneously, and a similar projection system (featuring stereophonic sound) gave the audience the impression of being surrounded by the sound and the image.1 Cinerama was used primarily for travelogue-type films with simple narratives. These travelogues were popular with the public, and at least a few narrative films were produced in the format. The most notable was How the West Was Won (1962). The system was cumbersome, however, and the technology was expensive. In the end, it was not economically viable.

20th Century–Fox's CinemaScope, however, was popular and cost effective, and it did prove to be successful. Beginning with The Robe (1953), CinemaScope appeared to be viable and the technology was rapidly copied by other studios. Using an anamorphic lens, the scenes were photographed on the regular 35-mm stock, but the image was squeezed. When projected normally, the squeezed image looked distorted, but when projected with an anamorphic lens, the image appeared normal but was presented wider than before (Figure 7.3).

The other notable wide-screen process of the period was VistaVision, Paramount Pictures’ response to CinemaScope. In this process, 35-mm film was run horizontally rather than vertically. The result was a sharper image and greater sound flexibility. The recorded image was twice as wide as the conventional 35-mm frame and somewhat taller. For VistaVision, Paramount selected a modified wide-screen aspect ratio of 1:1.85, the aspect ratio later adopted as the industry standard.

Figure 7.3 |

CinemaScope. Aspect ratio 1:2.55 (later reduced to 1:2.35). |

The larger 70mm, 65mm, TODD-AO, and Panavision 70 formats had an aspect ratio of 1:2.2, with room on the film for four magnetic soundtracks. Not only did the larger frame make possible a bigger sound, but it also allowed sharper images despite the size of the screen. Imax is similar to VistaVision in that it records 70-mm film run horizontally. Unlike VistaVision, which had a normal vertical projection system, Imax is projected horizontally and consequently requires its own special projection system. Its image is twice as large as the normal 70-mm production, and the resultant clarity is striking.

Of all of the formats, those that were economically viable were the systems that perfected CinemaScope technology, particularly Panavision. The early CinemaScope films exhibited problems with close-ups and with moving shots. By the early 1960s, when Panavision supplanted CinemaScope and VistaVision, those imperfections had been overcome, and the wide-screen had become the industry standard.2

Today, standard film has an aspect ratio of 1:1.85; however, films that have special releases—the big-budget productions that are often shot in anamorphic 35-mm and blown up to 70-mm—are generally projected 1:2.2 so that they are wider screen presentations. Films such as Hook (1991) or Terminator 2 (1991) are projected in a manner similar to the early CinemaScope films, and the problems for the editor are analogous.3

In the regular 1:1.33 format, the issues of editing—the use of close-ups, the shift from foreground to background, and the moving shot—have been developed, and both directors and audiences are accustomed to a particular pattern of editing. With the advent of a frame that was twice as wide, all of the relationships of foreground and background were changed.

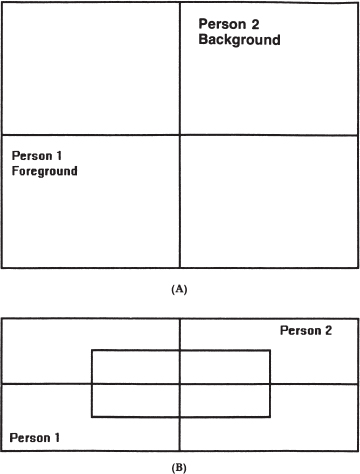

In Figure 7.4, two characters, one in the foreground and the other in the background, are shown in two frames, one a regular frame and the other a CinemaScope frame. In the CinemaScope frame, the characters seem farther apart, and there is an empty spot in the frame, creating an inner rectangle. This image affects the relationship implied between the two characters. The foreground and background no longer relate to one another in the same way because of the CinemaScope frame. Now the director also has the problem of the middle ground. The implications for continuity and dramatic meaning are clear. The wider frame changes meaning. The director and editor must recognize the impact of the wider frame in their work.

Figure 7.4 |

Foreground–background relationship in (A) Academy and (B) wide-screen formats. |

The width issue plays equal havoc for other continuity issues: match cuts, moving shots, and cuts from extreme long shot to extreme close-up. In its initial phase, the use of the anamorphic lens was problematic for close-ups because it distorted objects and people positioned too close to the camera. Maintaining focus in traveling shots, given the narrow depth of field of the lens, posed another sort of problem. The result, as one sees in the first CinemaScope film, The Robe, was cautious editing and a slow-paced style.

Some filmmakers attempted to use the wide screen creatively. They demonstrated that new technological developments needn't be ends unto themselves, but rather opportunities for innovation.

CHARACTER AND ENVIRONMENT

A number of filmmakers used the new wide-screen process to try to move beyond the action-adventure genres that were the natural strength of the wide screen. Both Otto Preminger and Anthony Mann made Westerns using CinemaScope, and although Mann later became one of the strongest innovators in its use, Preminger, in his film River of No Return (1954), illustrated how the new foreground–background relationship within the frame could suggest a narrative subtext critical to the story.

River of No Return exhibits none of the fast pacing that characterizes the dramatic moments in the Western Shane (1953), for example. Nor does it have the intense close-ups of High Noon (1952), a Western produced two years before River of No Return. These are shortcomings of the wide-screen process. What River of No Return does illustrate, however, is a knack for using shots to suggest the character's relationship to their environment and to their constant struggle with it. To escape from the Indians, a farmer (Robert Mitchum), his son, and an acquaintance (Marilyn Monroe) must make their way down the river to the nearest town. The rapids of the river and the threat of the Indians are constant reminders of the hostility of their environment. The river, the mountains, and the valleys are beautiful, but they are neither romantic nor beckoning. They are constant and indifferent to these characters. Because the environment fills the background of most of the images, we are constantly reminded about the characters’ context.

Preminger presented the characters in the foreground. The characters interact, usually in medium shot, in the foreground. We relate to them as the story unfolds; however, the background, the environment, is always present. Notable also is the camera placement. Not only is the camera placed close to the characters, but the eye level is democratic. The camera neither looks down or up at the characters. The result doesn't lead us; instead, it allows us to relate to the characters more naturally.

The pace of the editing is slow. Preminger's innovation was to emphasize the relationship of the characters to their environment by using the film format's greater expanse of foreground and background.

Preminger developed this relationship further in Exodus (1960). Again, the editing style is gradual even in the set-piece: the preparation for and the attack on the Acre prison. Two examples illustrate how the use of foreground and background sets up a particular relationship while avoiding the need to edit (Figure 7.5).

Early in the film, Ari Ben Canaan (Paul Newman) tries to take six hundred Jews illegally out of Cyprus to Palestine. His effort is thwarted by the British Navy. When the British major (Peter Lawford) or his commanding officer (Ralph Richardson) communicate with the Exodus, they are presented in the foreground, and the blockaded Exodus is presented in the same frame but in the background.

Figure 7.5 |

Exodus, 1960. ©1960 United Artists Pictures, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Later in the film, Ari Ben Canaan is showing Kitty, an American nurse (Eva Marie Saint), the location of his home. The scene takes place high atop a mountain overlooking the Jezreel Valley, the valley in which his home is located as well as the village of his Arab neighbors. In this shot, Ari explains to the nurse about the history of the valley, and the two of them acknowledge their attraction to one another. Close to the camera, Ari and Kitty speak and then embrace. The valley they speak about is visible in the background. Other filmmakers might have used an entire sequence of shots, including close-ups of the characters and extreme long shots of the valley. Preminger's widescreen shot thus replaces an entire sequence.

RELATIONSHIPS

In East of Eden (1955), Elia Kazan explored the relationship of people to one another rather than their relationship to the environment. The film considers the barriers between characters as well as the avenues to progress in their relationships.

East of Eden is the story of the “bad son” Cal (James Dean). His father (Raymond Massey) is a religious moralist who is quick to condemn his actions. The story begins with Cal's discovery that the mother he thought dead is alive and prospering as a prostitute in Monterey, 20 miles from his home.

Kazan used extreme angles to portray how Cal looks up to or down on adults. Only in the shots of Cal with his brother, Aaron, and his fiancee, Abra (Julie Harris), is the camera nonjudgmental, presenting the scenes at eye level. Whenever Cal is observing one of his parents, he is present in the foreground or background, and there is a barrier—blocks of ice or a long hallway, for example—in the middle. Kazan tilted the camera to suggest the instability of the family unit. This is particularly clear in the family dinner scene. This scene, particularly the attempt of father and son to be honest about the mother's fate, is the first sequence where cutting between father and son as they speak about the mother presents the distance between them. The foreground–background relationship is broken, and the two men so needy of one another are separate. They live in two worlds, and the editing of this sequence portrays that separateness as well as the instability of the relationship.

One other element of Kazan's approach is noteworthy. Kazan angled the camera placement so that the action either approaches the camera at an angle or moves away from the camera. In both cases, the placement creates a sense of even greater depth. Whereas Preminger usually had the action take place in front of the camera and the context directly behind the action of the characters, there appears a studied relationship of the two. Kazan's approach is more emotional, and the extra sense of depth makes the wide-screen image seem even wider. On one level, Kazan may have been exploring the possibilities, but in terms of its impact, this placement seems to increase the space, physical and emotional, between the characters.

RELATIONSHIPS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

RELATIONSHIPS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

No director was more successful in the early use of the wide-screen format than John Sturges, whose 1955 film Bad Day at Black Rock is an exemplary demonstration that the wide screen could be an asset for the editor. Interestingly, Sturges began his career as an editor.

John McCready (Spencer Tracy) is a one-armed veteran of World War II. It is 1945, and he has traveled to Black Rock, a small desert town, to give a medal to the father of the man who died saving his life. The problem is that father and son were Japanese-Americans, and this town has a secret. Its richest citizen, Reno Smith (Robert Ryan), and his cronies killed the father, Kimoko, in a drunken rage after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The townspeople try to cover up this secret, but McCready quickly discovers the truth. In 48 hours, McCready's principal mission, to give the Medal of Honor to a parent, turns into a struggle for his own survival.

The characters and the plot of Sturges's film are tight, tense, and terse. In terms of style, Sturges used almost no close-ups, and yet the tension and emotion of the story remain powerful. Sturges achieved this tension through his intelligent use of the wide screen and his application of dynamic editing in strategic scenes.

Two scenes notable for their dynamic editing are the train sequence that appears under the credits and the car chase scene in the desert. The primary quality of the train sequence is the barrenness of the land that the train travels through. There are no people, no animals, no signs of settlement. The manner in which Sturges filmed the train adds to the sense of the environment's vastness. Shooting from a helicopter, a truck and a tracking shot directly in front of the train, Sturges created a sense of movement. By alternating between angled shots that demonstrate the power of the train breaking through the landscape and flat shots in which train and landscape seem flattened into one, Sturges alternated between clash and coexistence. His use of high angles and later low angles for his shots adds to the sense of conflict.

Throughout this sequence, then, the movement and variation in camera placement and the cutting on movement creates a dynamic scene in which danger, conflict, and anticipation are all created through the editing. Where is the train going? Why would it stop in so isolated a spot? This sequence prepares the audience for the events and the conflicts of the story.

After introducing us to John McCready, Sturges immediately used the wide screen to present his protagonist in conflict with almost all of the townspeople of Black Rock. Sturges did not use close-ups; he favored the three-quarter shot, or American shot. This shot is not very emotional, but Sturges organized his characters so that the constant conflict within the shots stands in for the intensity of the close-up.

For example, as McCready is greeted by the telegraph operator at the train station, he flanks the left side of the screen, and the telegraph operator flanks the right. The camera does not crowd McCready. Although he occupies the foreground, the telegraph operator occupies the background. In the middle of the frame, the desert and the mountains are visible. The space between the two men suggests a dramatic distance between them. As in other films, Sturges could have fragmented the shot and created a sequence, but here he used the width of the frame to provide dramatic information within a single shot without editing.

Sturges followed the same principle in the interiors. As McCready checks into the hotel, he is again on the left of the frame, the hotel clerk is on the right, and the middle ground is unoccupied. Later in the same setting, the sympathetic doctor occupies the background, local thugs occupy the middle of the frame, and the antagonist, Smith, is in the left foreground. Sturges rarely left a part of the frame without function. When he used angled shots, he suggested power relationships opposed to one another, left to right, foreground to background. When he used flatter shots, those conflicting forces faced off against one another in a less interesting way, but nevertheless in opposition. Rather than relying on the clash of images to suggest conflict and emotional tension, Sturges used the wide-screen spaces and their organization to suggest conflict. He avoided editing by doing so, but the power and relentlessness of the conflict is not diminished because the power within the story is constantly shifting, as reflected in the visual compositions. By using the wide screen in this way, Sturges avoided editing until he really needed it. When he did resort to dynamic editing, as in the car chase, the sequence is all the more powerful as the pace of the film dramatically changes.

By using the wide screen fully as a dramatic element in the film, Sturges created a story of characters in conflict in a setting that can be used by those characters to evoke their cruelty and their power. The wide screen and the editing of the film both contribute to that evocation.

THE BACKGROUND

Max Ophuls used CinemaScope in Lola Montes (1955). Structurally interesting, the film is a retrospective examination of the life of Lola Montes, a nineteenth-century beauty who became a mistress to great musicians and finally to the King of Bavaria. The story is told in the present. A dying Lola Montes is the main attraction at the circus. As she reflects on her life, performers act out her reminiscences. Flashbacks of the younger Lola and key phases are intercut with the circus rendition of that phase. Finally, her life retold, Lola dies.

Ophuls, a master of the moving camera, was very interested in the past (background) and the present (foreground), and he constantly moved between them. For example, as the film opens, only the circus master (Peter Ustinov) is presented in the foreground. Lola (Martine Carol) and the circus performers are in the distant background. As the story begins, Lola herself is presented in the foreground, but as we move into the past story (her relationship with Franz Liszt, her passage to England, and her first marriage), Lola seems uncertain whether she is important or unimportant. What she wants (a handsome husband or to be grown up) is presented in the middle ground, and she fluctuates toward the foreground (with Liszt and later on the ship) or in the deep background (with Lieutenant James, who becomes her first husband). Interestingly, Lola is always shifting but never holding on to the central position, the middle of the frame. In this sense, the film is about the losses of Lola Montes because she never achieves the centrality of the men in her life, including the circus master.

The wide-screen shot is always full in this film, but predominantly concerns the barriers to the main character's happiness. The editing throughout supports this notion. If the character is in search of happiness, an elusive state, the editing is equally searching, cutting on movement of the character or the circus ensemble and its exploration/exploitation of Lola. The editing in this sense follows meaning rather than creates it.

By using the wide screen as he did, Ophuls gave primacy to the background of the shot over the foreground, to Lola's search over her success, to her victimization over her victory. The film stands out as an exploration of the wide screen. Ophul's work was not often imitated until Stanley Kubrick used the wide screen and movement in a similar fashion in Barry Lyndon (1975).

THE WIDE SCREEN AFTER 1960

The technical problems of early CinemaScope—the distortion of closeups and in tracking shots—were overcome by the development of the Panavision camera. It supplanted CinemaScope and VistaVision with a simpler system whose anamorphic projections offered a modified widescreen image with an aspect ratio of 1:1.85 and in its larger anamorphic use in 35-mm or 70-mm, it provided an image aspect ratio of 1:2.2. With the technical shortcomings of CinemaScope overcome, filmmakers began to edit sequences as they had in the past. Pace picked up, and close-ups and moving shots took on their past pattern of usage.

A number of filmmakers, however, made exceptional use of the wide screen and illustrated its strengths and weaknesses for editing. For example, Anthony Mann in El Cid (1961) used extreme close-ups and extreme long shots as well as framed single shots that embrace a close shot in the foreground and an extreme long shot in the background. Mann presented relationships, usually of conflict, within a single frame as well as within an edited sequence. The use of extreme close-ups and extreme long shots also elevated the nature of the conflict and the will of the protagonist. Because the film mythologizes the personal and national struggles of Rodrigo Diaz de Bivar, the Cid (Charlton Heston), those juxtapositions within and between shots are critical.

Mann also used the width of the frame to give an epic quality to each combat in which Rodrigo partakes: the personal fight with his future father-in-law, the combat of knights for the ownership of Calahorra, and the large-scale final battle on the beach against the Muslim invaders from North Africa. In each case, the different parts of the frame were used to present the opposing force. The clash, when it comes, takes place in the middle of the frame in single shots and in the middle of an edited sequence when single shots are used to present the opposing forces. Mann was unusually powerful in his use of the wide-screen frame to present forces in opposition and to include the land over which they struggle. Few directors have the visual power that Mann displayed in El Cid.

In his prologue in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Stanley Kubrick presents a series of still images that, together, are intended to create a sense of vast, empty, unpopulated space. This is the Earth at the dawn of humanity. Given the absence of continuity—the editing does not follow narrative action or a person in motion—the stills have a random, discontinuous quality, a pattern of shots such as Alexander Dovzhenko used in Earth (1930). Out of this pattern, an idea eventually emerges: the vast emptiness of the land. This sequence leads to the introduction of the apes and other animals. From our vantage point, however, the interest is in the editing of the sequence. Without cues or foreground–background relationships, these shots have a genuine randomness that, in the end, is the point of the sequence. There is no scientific gestalt here because there is no human here. The wide screen emphasizes the expanse and the lack of context.

A number of other filmmakers are notable for their use of the wide screen to portray conflict. Sam Peckinpah used close-ups in the foreground and background by using lenses that have a shallow depth of field. The result is a narrowing of the gap between one character on the left and another character, whether it be friend or foe, on the right. The result is intense and almost claustrophobic rather than expansive. Sergio Leone used the same approach in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1967). In the final gunfight, for example, he used close-ups of all of the combatants and their weapons. He presented the subject fully in two-thirds of the frame, allowing emptiness, some background, or another combatant to be displayed in the balance of the frame. Leone seemed to relish the overpowering close-ups, as if he were studying or dissecting an important event.

John Boorman, on the other hand, was more orthodox in his presentation of combatants in Hell in the Pacific (1968). The story, set in World War II, has only two characters: a Japanese soldier who occupies an isolated island and an American flyer who finds himself on the island after being downed at sea. These two characters struggle as combatants and eventually as human beings to deal with their situation. They are adversaries in more than two-thirds of the film, so Boorman presented them in opposition to one another within single frames (to the left and right) as well as in edited sequences. What is interesting in this film is how Boorman used both the wide screen and conventional options, including close-ups, cutaways, and faster cutting, to maintain and build tension in individual sequences. When he used the wide screen, the compositions are full to midshots of the characters. Because he didn't want to present one character as a protagonist and the other as the antagonist, he did not exploit subjective placement or close-ups. Instead, whenever possible, he showed both men in the same frame, suggesting the primacy of their relationship to one another. One may have power over the other temporarily, but Boorman tried to transcend the nationalistic, historical struggle and to reach the interdependent, human subtext. These two characters are linked by circumstance, and Boorman reinforced their interdependence by using the wide-screen image to try to overcome the narrative conventions that help the filmmaker demonstrate the victorious struggle of the protagonist over the lesser intentions of the antagonist.

Other notable filmmakers who used the wide screen in powerful ways include David Lean, who illustrated again and again the primacy of nature over character (Ryan's Daughter, 1970). Michelangelo Antonioni succeeded in using the wide screen to illustrate the human barriers to personal fulfillment (L'Avventura, 1960). Luchino Visconti used the wide screen to present the class structure in Sicily during the Risorgimento (Il Ovottepordo, 1962). Federico Fellini used the wide screen to create a powerful sense of the supernatural evil that undermined Rome (Fellini Satyricon, 1970). Steven Spielberg used subjective camera placement to juxtapose potential victim and victimizer, human and animal, in Jaws (1975), and Akira Kurosawa used color and foreground–background massing to tell his version of King Lear's struggle in Ran (1985). Today, the wide screen is no longer a barrier to editing but rather an additional option for filmmakers to use to power their narratives visually.

CINEMA VERITÉ

CINEMA VERITÉ

The wide screen forced filmmakers to give more attention to composition for continuity and promoted the avoidance of editing through the use of the foreground–background relationship. Cinema verité promoted a different set of visual characteristics for continuity.

Cinema verité is the term used for a particular style of documentary filmmaking. The post-war developments in magnetic sound recording and in lighter, portable cameras, particularly for 16-mm, allowed a less intrusive filmmaking style. Faster film stocks and more portable lights made film lighting less intrusive and in many filmmaking situations unnecessary. The cliché of cinema verité filmmaking is poor sound, poor light, and poor image. In actuality, however, these films had a sense of intimacy rarely found in the film experience, an intimacy that was the opposite of the wide-screen experience. Cinema verité was rooted in the desire to make real stories about real people. The Italian neorealist filmmakers—such as Roberto Rossellini (Open City, 1946), Vittorio DeSica (The Bicycle Thief, 1948), and Luchino Visconti (La Terra Trema, 1947)—were the leading influences of the movement.

Cinema verité, then, was a product of advances in camera and sound recording technology that made filmmaking equipment more portable than had previously been possible. That new portability allowed the earliest practitioners to go where established filmmakers had not been interested in going. Lindsay Anderson traveled to the farmers’ market in Covent Garden for Every Day Except Christmas (1957), Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson traveled to a jazz club for Momma Don't Allow (1955), Terry Filgate followed a Salvation Army parish in Montreal in Blood and Fire (1959), and D. A. Pennebaker followed Bob Dylan in Don't Look Back (1965). In each case, these films attempted to capture a sense of the reality of the lives of the characters, whether public figures or private individuals. There was none of the formalism or artifice of the traditional feature film.

How did cinema verité work? What was its editing style? Most cinema verité films proceeded without a script. The crew filmed and recorded sound, and a shape was found in the editing process.4 In editing, the problems of narrative clarity, continuity, and dramatic emphasis became paramount. Because cinema verité proceeded without staged sequences and with no artifical sound, including music, the raw material became the basis for continuity as well as emphasis.

Cinema verité filmmakers quickly understood that they needed many closeups to build a sequence because the conventions of the master shot might not be available to them. They also realized that general continuity would come from the sound track rather than from the visuals. Carrying over the sound from one shot to the next provided aural continuity, and this was sometimes the only basis for continuity in a scene. Consequently, the sound track became even more important than it had been in the dramatic film. Between the close-ups and the sound, continuity could be maintained. Sound could also be used to provide continuity among different sequences. As the movement gathered steam, cinema verité filmmakers also used intentional camera and sound mistakes, acknowledgments of the filmmaking experience, to cover for losses of continuity. The audience, after all, was watching a film, and acknowledgment of that fact proved useful in the editing. It joined audience and filmmaker in a moment of confession that bound the two together. The rough elements of the filmmaking process, anathema in the dramatic film, became part of the cinema verité experience; they supported the credibility of the experience.5 The symbols of cinema verité were those signposts of the hand-held camera: camera jiggle and poor framing.

Before exploring the editing style of cinema verité in more detail, it might be useful to illustrate how far-reaching its style of intimacy with the subject was to become. Beginning with the New Wave films of François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, cinema verité had a wide impact. Whatever their subject, young filmmakers across the world were attracted to this approach. In Hungary, Istvan Szabo (Father, 1966), in Czechoslovakia, Milos Forman (Fireman's Ball, 1968), in Poland, Jerzy Skolimowski (Hands Up, 1965) all adopted a style of reportage in their narrative films. Because the hand-held style of cinema verite had found its way into television documentary and news the style adopted by these filmmakers suggested the kind of veracity, of weightiness, of importance, found in the television documentary. They were not making television documentaries, though.

Nor were John Frankenheimer in Seconds (1966) or Michael Ritchie in The Candidate (1972), and yet the handheld camera shots and the allusions to television gave each film a kind of veracity unusual in dramatic films.6 The same style was taken up in a more self-exploratory way by Haskell Wexler in Medium Cool (1969). In these three films, the intimacy of cinema verité was borrowed and applied to a dramatized story to create the illusion of reality. In fact, the sense of realism resulting because of cinema verité made each film resemble in part the evening news on television. The result was remarkably effective.

Perhaps no dramatic film plays more on this illusion of realism deriving from cinema verité than Privilege (1967). Peter Watkins re-created the life of a rock star in a future time. Using techniques (even lines of dialogue) borrowed from the cinema verité film about Paul Anka (Lonely Boy, 1962), Watkins managed to reference rock idolatry in a manner familiar to the audience.

Watkins's attraction to cinema verité had been cultivated by two documentary-style films: The Battle of Culloden (1965) and The War Game (1967). Complete with on-air interviews and off-screen narrators, both films simulated documentaries with cinema verité techniques. However, both were dramatic re-creations using a style that simulated post-1950 type of reality. The fact that The War Game was banned from the BBC suggests how effective the use of those techniques were.

To understand how the cinema verité film was shaped given the looseness of its production, it is useful to look at one particular film to illustrate its editing style.

Lonely Boy was a production of Unit B at the National Film Board (NFB) of Canada. That unit, which was central in the development of cinema verité with its Candid Eye series, had already produced such important cinema verité works as Blood and Fire (1958) and Back-Breaking Leaf (1959). The French unit at the NFB had also taken up cinema verité techniques in such films as Wrestling (1960). Lonely Boy, a film about the popular young performer Paul Anka, brought together many of the talents associated with Unit B. Tom Daley was the executive producer, Kathleen Shannon was the sound editor, John Spotton and Guy L. Cote were the editors, and Roman Kroitor and Wolf Koenig were the directors. Each of these people demonstrated many talents in their work at and outside the NFB. Kathleen Shannon became executive producer of Unit D, the women's unit of the NFB. John Spotton was a gifted cinematographer (Memorandum, 1966). Wolf Koenig played an important role in the future of animation at the NFB. Tom Daley, listed as the executive producer on the film, has a reputation as one of the finest editors the NFB ever produced.

Lonely Boy is essentially a concert film, the predecessor of such rock performance films as Gimme Shelter (1970), Woodstock (1970), and Stop Making Sense (1984). The 26-minute film opens and closes on the road with Paul Anka between concerts. The sound features the song “Lonely Boy.” Within this framework, we are presented with, as the narrator puts it, a “candid look” at a performer moving up in his career. To explore the “phenomenon,” Kroiter and Koenig follow Paul Anka from an outdoor performance in Atlantic City to his first performance in a nightclub, the Copacabana, and then back to the outdoor concert. In the course of this journey, Anka, Irving Feld (his manager), Jules Podell (the owner of the Copacabana), and many fans are interviewed. The presentation of these interviews makes it unclear whether the filmmakers are seeking candor or laughing at Anka and his fans. Their attitude seems to change. Anka's awareness of the camera and retakes are included here to remind us that we are not looking in on a spontaneous or candid moment but rather at something that has been staged (Figures 7.6 to 7.8).

The audience is exposed to Anka, his manager, and his fans, but it is not until the penultimate sequence that we see Anka in concert in a fuller sense. The screen time is lengthy compared to the fragments of concert performance earlier in the film. Through his performance and the reaction of the fans, we begin to understand the phenomenon. In this sequence, the filmmakers seem to drop their earlier skepticism, and in this sense, the sequence is climactic.

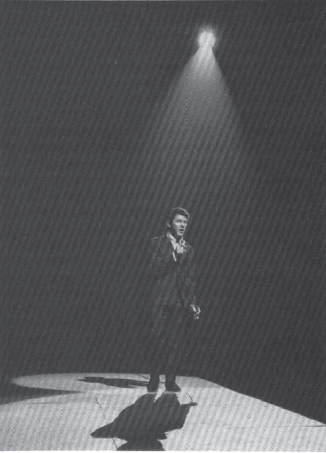

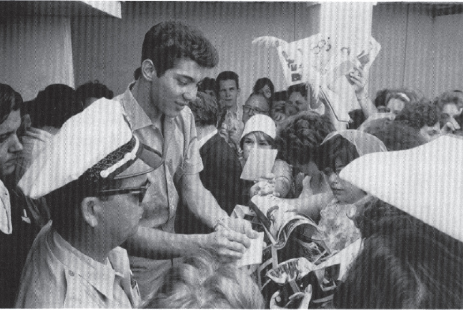

Figure 7.6 |

Lonely Boy, 1962. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada. |

Throughout the film, the sound track unifies individual sequences. For example, the opening sequence begins on the road with the song “Lonely Boy” on the sound track. We see images of Atlantic City, people enjoying the beach, a sign announcing Paul Anka's performance, shots of teenagers, the amusement park, and the city at night. Only as the song ends does the film cut to Paul Anka finishing the song. Then we see the response of his audience.

Figure 7.7 |

Lonely Boy, 1962. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada. |

Figure 7.8 |

Lonely Boy, 1962. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada. |

The shots in this sequence are random. Because many are close-ups intercut with long shots, unity comes from the song on the sound track. Between tracking shots, Kroiter and Koenig either go from movement within a shot, i.e., the sign announcing Anka's performance, to a tracking shot of teenagers walking—movement of the shot to movement within the shot. Again, overall unity comes from the sound track.

In the next sequence, Anka signs autographs, and the general subject (how Anka's fans feel about him) is the unifying element. This sequence features interviews with fans about their zeal for the star.

In all sequences, visual unity is maintained through an abundance of closeups. A sound cue or a cutaway allows the film to move efficiently into the next sequence.

In the final sequence, the concert performance, the continuity comes from the performance itself. The cutaways to the fans are more intense than the performance shots, however, because the cutaways are primarily close-ups. These audience shots become more poignant when Kroiter and Koenig cut away to a young girl screaming and later fainting. In both shots, the sound of the scream is omitted. We hear only the song. The absence of the sound visually implied makes the visual even more effective. The handheld quality of the shots adds a nervousness to the visual effect of an already excited audience. In this film, the handheld close-up is an asset rather than a liability. It suggests the kind of credibility and candor of which cinema verité is capable.

Lonely Boy exhibits all of the characteristics of cinema verité: for example, too much background noise in the autograph sequence and a jittery handheld camera in the backstage sequence where Anka is quickly changing before a performance. In the latter, Anka acknowledges the presence of the camera when he tells a news photographer to ignore the filmmakers. All of this—the noise level, the wobbly camera, the acknowledgment that a film is being made—can be viewed as technical shortcomings or amateurish lapses, or they can work for the film to create a sense of candor, insight, honesty, and lack of manipulation: the agenda for cinema verité. The filmmakers try to have it all in this film. What they achieve is only the aura of candor. The film is fascinating, nevertheless.

Others who used the cinema verité approach—Allan King in Warrendale (1966), Fred Wiseman in Hospital (1969), Alfred and David Maysles in Salesman (1969)—exploited cinema verité fully. They achieved an intimacy with the audience that verges on embarrassing but, at its best, is the type of connection with the audience that was never possible with conventional cinematic techniques.

Cinema verité must be viewed as one of the few technological developments that has had a profound impact on film. Because it is so much less structured and formal than conventional filmmaking, it requires even greater skill from its directors and, in particular, its editors.