9 |

The Influence of Television and Theatre |

||

TELEVISION

TELEVISION

No post-war change in the entertainment industry was as profound as the change that occurred when television was introduced. Not only did television provide a home entertainment option for the audience, thereby eroding the traditional audience for film, it also broadcast motion pictures by the 1960s. By presenting live drama, weekly series, variety shows, news, and sports, television revolutionized viewing patterns, subject matter, the talent pool,1 and, eventually, how films were edited.

Perhaps television's greatest asset was its sense of immediacy, a quality not present in film. Film was consciously constructed, whereas television seemed to happen directly in front of the viewer. This sense was supported by the presentation of news events as they unfolded as well as the broadcasting of live drama and variety shows. It was also supported by television's function as an advertising medium. Not only were performers used in advertising, but the advertising itself—whether a commercial of 1 minute or less—came to embody entertainment values. News programs, commercials, and how they were presented (particularly their sense of immediacy and their pace) were the influences that most powerfully affected film editing.

One manifestation of television's influence on film can be seen in the treatment of real-life characters or events. Film had always been attracted to biography; Woodrow Wilson, Lou Gehrig, Paul Ehrlich, and Louis Pasteur, among others, received what has come to be called the “Hollywood treatment.” In other words, their lives were freely and dramatically adapted for film. There was no serious attempt at veracity; entertainment was the goal.

After television came on the scene, this changed. The influence of television news was too great to ignore. Veracity had to in some way be respected. This approach was supported by the post-war appeal of neorealism and by the cinema verité techniques. If a film looked like the nightly news, it was important, it was real, it was immediate.

Peter Watkins recognized this in his television docudramas of the 1960s (The Battle of Culloden, 1965; The War Game, 1967). He continued with this approach in his later work on Edward Munch. In the feature film, this style began to have an influence as early as John Frankenheimer's The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and was continued in his later films, Seven Days in May (1964) and Black Sunday (1977). Alan J. Pakula took a docudrama approach to Watergate in All the President's Men (1976), and Oliver Stone continues to work in this style, from Salvador (1986) to JFK (1991).

The docudrama approach, which combines a cinema verité style with jump-cut editing, gives films a patina of truth and reality that is hard to differentiate from the nightly news. Only the pace differs, heightening the tension in a way rarely seen on television news programs. Given that the subject, character, or event already has a public profile, the filmmaker need only dip back into that broadcast-created impression by using techniques that allude to veracity to make the film seem real. This is due directly to the techniques of television news: cinema verité, jump-cutting, and on- or off-air narrators. The filmmaker has a fully developed repertoire of editing techniques to simulate the reality of the nightly news.

The other manifestation of the influence of television seems by comparison fanciful, but its impact, particularly on pace, has been so profound that no film, television program, or television commerical is untouched by it. This influence can be most readily seen in the 1965–70 career of one man, Richard Lester, an expatriate American who directed the two Beatles’ films, A Hard Day's Night (1964) and Help! (1965) in Great Britain.

Using techniques widely deployed in television, Lester found a style commensurate with the zany mix of energy and anarchy that characterized the Beatles. One might call his approach to these films the first of the music videos.

Films that starred musical or comedy performers who were not actors had been made before. The Marx Brothers, Abbott and Costello, and Mario Lanza are a few of these performers. The secret for a successful production was to combine a narrative with opportunities for the performers to do what they did best: tell anecdotes or jokes or sing. Like the Marx Brothers’ films, A Hard Day's Night and Help! do have narratives. A Hard Day's Night tells the story of a day in the life of the Beatles, leading up to a big television performance. Help! is more elaborate; an Indian sect is after Ringo for the sacred ring he has on his finger. They want it for its spiritual significance. Two British scientists are equally anxious to acquire the ring for its technological value. The pursuit of the ring takes the cast around the world.

The stories are diversions from the real purpose of the films: to let the Beatles do what they do best. Lester's contribution to the two films is the methods he used to present the music. Notably, no two songs are presented in the same way.

The techniques Lester used are driven by a combination of cinema verité techniques with an absurdist attitude toward narrative meaning. Lester deployed the same techniques in his famous short film, Running, Jumping and Standing Still (1961).

Lester filmed the Beatles’ performances with multiple cameras. He intercut close-ups with extreme angularity—for example, a juxtaposition of George Harrison and Paul McCartney or a close-up of John Lennon—with the reactions of the young concert-goers.

The final song performed in A Hard Day's Night is intercut with the frenzy of the audience. Shots ranging from close-ups to long shots of the performers and swish pans to the television control booth and back to the audience were cut with an increasing pace that adds to the building excitement. The pace becomes so rapid, in fact, that the individual images matter less than the feeling of energy that exists between the Beatles and the audience. Lester used editing to underscore this energy.

Lester used a variety of techniques to create this energy, ranging from wide-focus images that distort the subject to extreme close-ups. He included handheld shots, absurd cutaways, speeded-up motion, and obvious jump cuts.

When the Beatles are performing in a television studio, Lester began the sequence with a television camera's image of the performance and pulled back to see the performance itself. He intercut television monitors with the actual performance quite often, thus referencing the fact that this is a captured performance. He did not share the cinema verité goal of making the audience believe that what they are watching is the real thing.

He set songs in the middle of a field surrounded by tanks or on a ski slope or a Bahamian beach. The location and its character always worked with his sense of who the Beatles were.

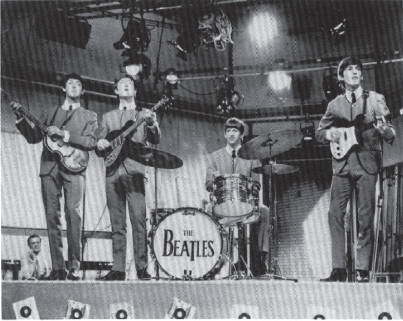

A Hard Day's Night opens with a large group of fans chasing the Beatles into a train station. The handheld camera makes the scene seem real, but when the film cuts to an image of a bearded Paul McCartney sitting with his grandfather and reading a paper, the mix of absurdity and reality is established. Pace and movement are always the key. Energy is more important in this film than realism, so Lester opted to jump-cut often on movement. The energy that results is the primary element that provides emotional continuity throughout the film (Figure 9.1).

Lester was able to move so freely with his visuals because of the unity provided by the individual songs. Where possible, he developed a medley around parallel action. For example, he intercut shots of the Beatles at a disco with Paul's grandfather at a gambling casino. By finding a way to intercut sequences, Lester moved between songs and styles. He didn't even need to have the Beatles perform the songs. They could simply act during a song, as they do in “All My Loving.” This permitted some variety within sequences and between’ sequences. All the while, this variety suggests that anything is possible, visually or in the narrative. The result is a freedom of choice in editing virtually unprecedented in a narrative film. Not even Bob Fosse in All That Jazz (1979) had as much freedom as Lester embraced in A Hard Day's Night.

Lester's success in using a variety of camera angles, images, cutaways, and pace has meant that audiences are willing to accept a series of diverse images unified only by a sound track. The accelerated pace suggests that audiences are able to follow great diversity and find meaning faster. The success of Lester's films suggests, in fact, that faster pace is desirable. The increase in narrative pace since 1966 can be traced to the impact of the Beatles’ films.

Figure 9.1 |

A Hard Day's Night, 1964. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Not only have narrative stories accelerated,2 so too has the pace of the editing. As can be seen in Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch (1969) and Martin Scorsese's Raging Bull (1980), individual shots have become progressively shorter. This is nowhere better illustrated than in contemporary television commercials and music videos.

Richard Lester exhibited in the “Can't Buy Me Love” sequence in A Hard Days Night, the motion, the close-ups, the distorted wide-angle shots of individual Beatles and of the group, the jump cutting, the helicopter shots, the slow motion, and the fast motion that characterize his work. Audience's acceptance and celebration of his work suggest the scope of Lester's achievement—freedom to edit for energy and emotion, uninhibited by traditional rules of continuity. By using television techniques, Lester liberated himself and the film audience from the realism of television, but with no loss of immediacy. Audiences have hungered for that immediacy, and many filmmakers, such as Scorsese, have been able to give them the energy that immediacy suggests.

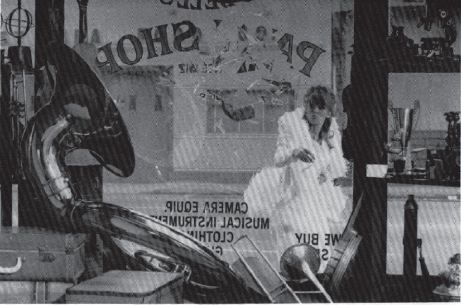

Lester went on to use these techniques in an uneven fashion. Perhaps his most successful later film was Petulia (1968), which was set in San Francisco. In this story about the breakup of a conventional marriage, Lester was particularly adept at moving from past to present and back to fracture the sense of stability that marriage usually implies. The edgy moving camera also helped create a sense of instability (Figure 9.2). Lester's principal contribution to film editing was the freedom and pace he was able to achieve in the two Beatles’ films.

THEATRE

THEATRE

If the influence of television in this period was related to the search for immediacy, the influence of theatre was related to the search for relevance. The result of these influences was a new freedom with narrative and how narrative was presented through the editing of film.

During the 1950s, perhaps no other filmmaker was as influential as Ingmar Bergman. The themes he chose in his films—relationships (Lesson in Love, 1954), aging (Wild Strawberries, 1957), and superstition (The Magician, 1959)—suggested a seriousness of purpose unusual in a popular medium such as film. However, it was in his willingness to deal with the supernatural that Bergman illustrated that the theatre and its conventions could be accepted in filmic form. Bergman used film as many had used the stage: to explore as well as to entertain. Because the stage was less tied to realism, the audience was willing to accept less reality-bound conventions, thus allowing the filmmaker to explore different treatments of subject matter. When Bergman developed a film following, he also developed the audience's tolerance for theatrical approaches in film.

Figure 9.2 |

Petulia, 1968. ©1968 Warner Bros.-Seven Arts and Petersham Films (Petulia) Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

This is not to say that plays were not influential on film until Bergman came on the scene. As mentioned in Chapter 4, they had been. The difference was that the 1950s were notable for the interest in neorealist or cinema verité film. Even Elia Kazan, a man of the theatre, experimented with cinema verité in Panic in the Streets (1950). In the same period, however, he made A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). His respect for the play was such that he filmed it as a play, making no pretense that it was anything else.

Bergman, on the other hand, attempted to make a film with the thematic and stylistic characteristics of a play. For example, Death is a character in The Seventh Seal (1956). He speaks like other characters, but his costume differentiates him from them. Bergman's willingness to use such theatrical devices made them as important for editing as the integration of the past was in the films of Alain Resnais and as important as fantasy was in the work of Federico Fellini.

Bergman remained interested in metaphor and nonrealism in his later work. From the Life of the Marionettes (1980) uses the theatrical device of stylized repetition to explore responsibility in a murder investigation. Bergman used metaphor to suggest embroyonic Nazism in 1923 Germany in The Serpent's Egg (1978). Both films have a sense of formal design more closely associated with the theatrical set than with the film location. In each case, the metaphorical approach makes the plot seem fresh and relevant.

At the same time that Bergman was influencing international film, young critics-turned-filmmakers in England were also concerned about making their films more relevant than those made in the popular national cinema tradition. Encouraged by new directors in the theatre, particularly the realist work of John Osborne, Arnold Wesker, and Shelagh Delaney, directors Tony Richardson, Lindsay Anderson, and Karel Reisz—filmmakers who began their work in documentary film—very rapidly shifted toward less naturalistic films to make their dramatic films more relevant. They were joined by avant-garde directors, such as Peter Brook, who worked in both theatre and film and attempted to create a hybrid embracing the best elements of both media. This desire for relevance and the crossover between theatre and film has continued to be a central source of strength in the English cinema. The result is that some key screenwriters have been playwrights, including Harold Pinter, David Mercer, David Hare, and Hanif Kureishi. In the case of David Hare, the crossover from theatre to film has led to a career in film direction. Had Joe Orton lived, it seems likely that he, too, would have become an important screenwriter.

All of these playwrights share a serious interest in the nature of the society in which they live, in its class barriers, and in the fabric of human relationships that the society fosters. Beginning with Tony Richardson and his film adaptation of Osborne's Look Back in Anger (1958), the filmmakers of the British New Wave directed realist social dramas. Karel Reisz followed with Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960), and Lindsay Anderson followed with This Sporting Life (1963). With the exception of the latter film, the early work is marked by a strong cinema verité influence, as evidenced by the use of reallocations and live sound full of local accents and a reluctance to intrude with excessive lighting and the deployment of color. This “candid eye” tradition was later carried on by Ken Loach (Family Life, 1972) until recently. The high point for the New Wave British directors, however, came much earlier with Richardson's The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962). Later, each director yielded to the influence of the theatre and nonrealism. Indeed, the desertion of realism suggests that it was the seriousness of the subject matter of the early realist films rather than the philosophical link to the cinema verité style that appealed to Richardson, Anderson, and Reisz. In their search for an appropriate style for their later films, these filmmakers displayed a flexibility of approach that was unusual in film. The result again was to broaden the organization of images in a film.

The first notable departure from realism was Tony Richardson's Tom Jones (1963). Scripted by playwright John Osborne, the film took a highly stylized approach to Henry Fielding's novel. References to the silent film technique—including the use of subtitles and a narrator—framed the film as a cartoon portrait of social and sexual morality in eighteenth-century England.

To explore those mores, Richardson used fast motion, slow motion, stop motion, jump-cutting, and cinema verité handheld camera shots. He used technique to editorialize upon the times that the film is set in, with Tom Jones (Albert Finney) portrayed as a rather modern nonconformist. In keeping with this sense of modernity, two characters—Tom's mother and Tom—address the audience directly, thus acknowledging that they are characters in a film. With overmodulated performances more suited for the stage than for film, Richardson achieved a modern cartoon-like commentary on societal issues, principally class. Tom's individuality rises above issues of class, and so, in a narrative sense, his success condemns the rigidity of class in much the same way as Osborne and Richardson had earlier in Look Back in Anger. The key element in Tom Jones is its sense of freedom to use narrative and technical strategies that include realism but are not limited by a need to seem realistic. The result is a film that is far more influenced by the theatre than Richardson's earlier work. Richardson continued this exploration of form in his later films, The Loved One (1965) and Laughter in the Dark (1969).

Karel Reisz also abandoned realism, although thematically there are links between Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and his later Morgan (1966) and Isadora (1969).

Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment tells the story of the mental disintegration of the main character in the face of the disintegration of his marriage. Morgan (David Warner), a life-long Marxist with working-class roots, has married into the upper class. This social and political layer to his mental collapse is largely a factor in the failure of Morgan's marriage, but it is his reaction to the failure that gives Reisz the opportunity to visualize that disintegration. Morgan sees the world in terms of animals. He sees himself as a gorilla. A beautiful woman on a subway escalator is a peacock; a ticket seller is a hippopotamus. When he makes love with his ex-wife, they are two zebras rolling around on the veldt. Conflict, particularly with his ex-wife's lover, is a matter for lions. Whenever Morgan finds himself in conflict, he retreats into the animal world.

Reisz may have viewed Morgan's escape as charming or as a political response to his circumstances. In either case, the integration of animal footage throughout the film creates an allegory rather than a portrait of mental collapse. The realist approach to the same subject was taken by Ken Loach in Family Life (sometimes called Wednesday's Child). Reisz's approach, essentially metaphorical, yields a stylized film. In spite of the realist street sense of much of the footage, David Mercer's clever dialogue and the visual allusions create a hybrid film.

The same is true of Isadara, a biography of the great dancer Isadora Duncan (Vanessa Redgrave). Duncan had a great influence on modern dance, and she was a feminist and an aesthete. To re-create her ideas about life and dance, Reisz structured the film on an idea grid. The film jumps back and forth in time from San Francisco in 1932 to France in 1927. In between these jumps, the film moves ahead, but always in the context of looking at Duncan in retrospect to the scenes of 1927 in the south of France.

Reisz was not content simply to tell her biography. He also tried to re-create the inspiration for her dances. When she first makes love to designer Edward Gordon Craig (James Fox), the scene is crosscut with a very sensual dance. The dance serves as an expression of Duncan's feelings at that moment and as an expression of her inspiration. Creation and feeling are linked.

The film flows back and forth in time and along a chronology of her artistic development. Although much has been made of the editing of the film and its confusion, it is clearly an expression of its ambition. Reisz attempted to find editing solutions for difficult abstract ideas, and in many cases, the results are fascinating. The film has little connection to Reisz's free cinema roots, but rather is connected to dance and the theatre.

Lindsay Anderson was the least linked to realism of the three filmmakers. O'Dreamland (1953) moves far away from naturalism in its goals, and in his first feature, This Sporting Life, Anderson showed how far from realism his interests were. This story about a professional rugby player (Richard Harris) is also about the limits of the physical world. He is an angry man incapable of understanding his anger or of accepting his psychic pain. Only at the end does he understand his shortcomings. Of the three filmmakers, Anderson seems most interested in existential, rather than social or political, elements. At least, this is the case in This Sporting Life.

When he made If-.-.-.-(1969), Anderson completely rejected realism. For this story about rebellion in a public boy's school, Anderson used music, the alternating of black and white with color, and stylized, nonrealistic images to suggest the importance of freedom over authority and of the individual over the will of the society. By the end of the film, the question of reality or fantasy has become less relevant. The film embraces both fantasy and reality, and it becomes a metaphor for life in England in 1969. The freedom to edit more flexibly allowed Anderson to create his dissenting vision.

Anderson carried this theatrical approach even further in his next film, O Lucky Man! (1973). This film is about the actor who played Mick in If.-.-.-.-It tells the story of his life up to the time that he was cast in If.-.-.-.-The film is not so much a biography as it is an odyssey. Mick Travis is portrayed by Malcolm McDowell, but in O Lucky Man! he is presented as a Candide-like innocent. His voyage begins with his experiences as a coffee salesman in northern England, but the realism of the job is not of interest. His adventures take him into technological medical experimentation, nuclear accidents, and international corporate smuggling. Throughout, the ethics of the situation are questionable, the goals are exploitation at any cost: human or political. At the end of the film, the character is in jail, lucky to be alive.

Throughout O Lucky Man!, Anderson moved readily through fact and fantasy. A man who is both pig and man is one of the most repellent images. To provide a respite between sequences, Anderson cuts to Alan Price and his band as they perform the musical sound track of the film. Price later appears as a character in the film.

The overall impact of the film is to question many aspects of modern life, including medicine, education, industry, and government. The use of the theatrical devices of nonrealism, Brechtian alienation, and the naive main character allowed Anderson freedom to wander away from the narrative at will. The effect is powerful. When he was not making films, Anderson directed theatre. O Lucky Man!, with its focus on ideas about society, is more clearly a link to that theatrical experience than to Anderson's previous film, Every Day except Christmas (1957).

Not to be overlooked in this discussion of British directors is John Schlesinger. He also began in documentary. He produced an award-winning documentary, Terminus (1960), went on to direct a realist film, A Kind of Loving (1962), and, like his colleagues, began to explore the nonrealist possibilities.

Billy Liar (1963) is one of the most successful hybrid films. Originally a novel and then a play by Keith Waterhouse and Willis Hall, the story of Billy Fisher is the quintessential film about refusing to come of age.

Billy Fisher (Tom Courtenay) lies about everything: his family, his friends, his talents. Inevitably, those lies get him into trouble, and his charm cannot extricate him. He retreats into his fantasy world, Ambrosia, where he is general, king, and key potentate.

The editing is used to work Billy's fantasies into the film. Schlesinger straight-cut the fantasies as if they were happening as part of the developing action. If Billy's father or employer says something objectionable to Billy, the film straight-cuts to Billy in uniform, machine-gunning the culprit to death. If Billy walks, fantasizing about his fame, the film straight-cuts to the crowds for a soccer match. Schlesinger intercuts with the potentate Billy in uniform speaking to the masses. Before the speech, they are reflective; after it, they are overjoyed. Then the film cuts back to Billy walking in the town or in the glen above the town.

Billy is inventive, charming, and involving as a main character, but it is the integration of his fantasy life into the film that makes the character and the film engage us on a deeper level. The editing not only gives us insight into the private Billy, it also allows us to indulge in our own fantasies. To the extent that we identify with Billy, we are given license to a wider range of feeling than in many films. By using nonrealism, Schlesinger strengthened the audience's openness to theatrical devices in narrative films. He used them extensively in his successful American debut, Midnight Cowboy (1969).

No discussion of the influence of theatre on film would be complete without mention of Peter Brook. In a way, his work in film has been as challenging as his work in theatre. From Marat/Sade (1966) to his more recent treatment with Jean-Claude Carriere of Maharabata (1990), Brook has explored the mediation between theatre and film. His most successful hybrid film is certainly Marat/Sade.

The story is best described by the full title of the play: Marat/Sade (The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade). The playwright Peter Weiss was interested in the interfaces between play and audience, between madness and reality, and between historical fact and fiction. He used the set as well as the dramaturgy to provoke consideration of his ideas, and he mixed burlesque with realism. He used particular characters to “debate” positions, particularly the spirit of revolution and its bloody representative, Marat, and the spirit of the senses and its cynical representative, the Marquis de Sade.

The play, written and produced 20 years after World War II, ponders issues arising out of that war as well as issues central to the 1960s: war, idealism, politics, and a revolution of personal expectations. The work blurs the question: Who is mad, who is sane, and is there a difference?

The major problem that Brook faced was how to make the play relevant to a film audience. (The film was produced by United Artists.)

Brook chose to direct this highly stylized theatrical piece as a documentary.3 He used hand-held cameras, intense close-ups, a reliance on the illusion of natural light from windows, and a live sound that makes the production by the inmates convincing. Occasionally, the film cuts to an extreme long shot showing the barred room in which the play is being presented. It also cuts frequently to the audience for the performance: the director of the asylum and two guests. Cutaways to nuns and guards in the performance area also remind us that we are watching a performance.

In essence, Marat/Sade is a play within a play within a film. Each layer is carefully created and supported visually. When the film cuts to the singing chorus, we view Marat/Sade as a play. When it cuts to the audience and intercuts their reactions with the play, Marat/Sade is a play within a play. When Charlotte Corday (Glenda Jackson in her film debut) appears in a close-up, a patient attempts to act as Corday would, or the Marquis de Sade (Peter Magee) directs his performers, Marat/Sade becomes a film.

Because Marat/Sade is a film about ideas, Brook chose a hybrid approach to make those ideas about politics and sanity meaningful to his audience. The film remains a powerful commentary on the issues and a creative example of how theatre and film can interface.