10 |

New Challenges to Filmic Narrative Conventions |

||

The international advances of the 1950s and the technological experiments in wide screen and documentary techniques provided the context for the influence of television and theatre in the 1960s and 1970s. The sum effect was twofold: to make the flow of talent and creative influence more international than ever and, more important, to signal that innovation, whether its source was new or old, was critical. Indeed, the creative explosion of the 1950s and 1960s was nothing less than a gauntlet, a challenge to the next generation to make artful what was ordinary and to make art from the extraordinary. The result was an explosion of individualistic invention that has had a profound effect on how the partnership of sound and image has been manipulated. The innovations have truly been international, with a German director making an American film (Paris, Texas, 1984) and an American director making a European film (Barry Lyndon, 1975).

This chapter reviews many of the highlights of the period 1968–1988, focusing primarily on those films and filmmakers who challenged the conventions of film storytelling. In each case, the editing of sound and image is the vehicle for that challenge.

PECKINPAH: ALIENATION AND ANARCHY

PECKINPAH: ALIENATION AND ANARCHY

Sam Peckinpah's career before The Wild Bunch (1969) suggested his preference for working within the Western genre, but nothing in the style of his earlier Westerns, Ride the High Country (1962) and Major Dundee (1965), suggested his overwhelming reliance on editing in The Wild Bunch. Thematically, the passing of the West and of its values provides the continuity between these films and those that followed, primarily The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970) and Junior Bonner (1972). Peckinpah's later films, whether in the Western genre (Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, 1974) or the gangster genre (The Getaway, 1972) or the war genre (Cross of Iron, 1977), refer back to the editing style of The Wild Bunch; theme and editing style fuse to create a very important example of the power of editing.

The Wild Bunch was not the first film to explore violence by creating an editing pattern that conveyed the horror and fascination of the moment of death. The greatest filmmaker to explore the moment of death, albeit in a highly politicized context, was Sergei Eisenstein. The death of the young girl and the horse on the bridge in October (1928) and, of course, the Odessa Steps sequence in Potemkin (1925) are among the most famous editing sequences in history. Both sequences explore the moment of death of victims caught in political upheavals.

Later films, such as Fred Zinnemann's High Noon (1952), focus on the anticipation and anxiety of that moment when death is imminent. Robert Enrico's An Occurrence at Owl Creek (1962) is devoted in its entirety to the desire-to-live fantasy of a man in the moment before he is hanged. The influential Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Arthur Penn's exploration of love and violence, no doubt had a great impact on Peckinpah's choice of editing style.

Peckinpah's film recounts the last days of Bishop Pike (William Holden) and his “Wild Bunch,” outlaws who are violent without compunction—not traditional Western heroes. Pursued by railroad men and bounty hunters, they flee into Mexico where they work for a renegade general who seems more evil than the outlaws or the bounty hunters. Each group is portrayed as lawless and evil. In this setting of amorality, the Wild Bunch become heroic.

No description can do justice to Peckinpah's creation of violence. It is present everywhere, and when it strikes, its destructive force is conveyed by all of the elements of editing that move audiences: close-ups, moving camera shots, composition, proximity of the camera to the action, and, above all, pace. An examination of the first sequence in the film and of the final gunfight illustrates Peckinpah's technique.

In the opening sequence, the Wild Bunch, dressed as American soldiers, ride into a Texas town and rob the bank. The robbery was anticipated, and the railroad men and bounty hunters, coordinated by Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan), a former member of the Wild Bunch, have set a trap for Bishop Pike and his men. Unfortunately, a temperance meeting begins to march toward the bank. The trap results in the deaths of more than half of the Wild Bunch, but many townspeople are also killed. Pike and four of his men escape.

This sequence can be broken down into three distinct phases: the 5½minute ride into town, the 4½-minute robbery, and the 5-minute fight to escape from the town. The pace accelerates as we move through the phases, but Peckinpah relies on narrative techniques to amplify his view of the robbery, the law, and the role of violence in the lives of both the townspeople and the criminals. Peckinpah crosscuts between four groups throughout the sequence: the Wild Bunch, the railroad men and the bounty hunters, the religious town meeting, and a group of children gathered on the outskirts of town. The motif of the children is particularly important because it is used to open and close the sequence.

The children are watching a scorpion being devoured by red ants. In the final phase, the children destroy the scorpion and the red ants. If Peckinpah's message was that in this world you devour or are devoured, he certainly found a graphic metaphor to illustrate his message. The ants, the scorpion, and the children are shown principally in close-ups. In fact, close-ups are extensively used throughout the sequence.

In terms of pace, there is a gradual escalation of shots between the first two phases. The ride of the Wild Bunch into town has 65 shots in 5½ minutes. The robbery itself has 95 shots in 4½ minutes. In the final phase, the fight to escape from the town, a 5-minute section, the pace rapidly accelerates. This section has two hundred shots with an average length of 1½ seconds.

The final sequence is interesting not only for the use of intense close-ups and quick cutting, but also for the number of shots that focus on the moment of death. Slow motion was used often to draw out the instant of death. One member of the Wild Bunch is shot on horseback and crashes through a storefront window. The image is almost lovingly recorded in slow motion. What message is imparted? The impact is often a fascination with and a glorification of that violent instant of death. The same lingering treatment of the destruction of the scorpion and the ants underscores the cruelty and suffering implicit in the action.

The opening sequence establishes the relentless violence that characterizes the balance of the film. The impact of the opening sequence is almost superseded by the violence of the final gunfight. In this sequence, Pike and his men have succeeded in stealing guns for the renegade General Mapache. They have been paid, but Mapache has abducted the sole Mexican member of the Wild Bunch, Angel (Jaime Sanchez). Earlier, Angel had killed Mapache's mistress, a young woman Angel had claimed as his own. Angel had also given guns to the local guerrillas who were fighting against Mapache. Mapache has tortured Angel, and Pike and his men feel that they must stand together; they want Angel back. In this last fight, they insist on Angel's return. Mapache agrees, but slits Angel's throat in front of them. Pike kills Mapache. A massacre ensues in which Pike and the three remaining members of the Wild Bunch fight against hundreds of Mapache's soldiers. Many die, including all of the members of the Wild Bunch.

The entire sequence can be broken down into three phases: the preparation and march to confront Mapache, the confrontation with Mapache up to the deaths of Angel and Mapache, and the massacre itself (Figure 10.1). The entire sequence is 10 minutes long. The march to Mapache runs 3 minutes and 40 seconds. There are 40 shots in the march sequence; the average shot is almost 6 seconds long. In this sequence, zoom shots and camera motion are used to postpone editing. The camera follows the Wild Bunch as they approach Mapache.

The next phase, the confrontation with Mapache, runs 1 minute and 40 seconds and contains 70 shots. The unpredictability of Mapache's behavior and the shock of the manner in which he kills Angel leads to greater fragmentation and an acceleration of the pace of the sequence. Many close-ups of Pike, the Wild Bunch, and Mapache and his soldiers add to the tension of this brief sequence.

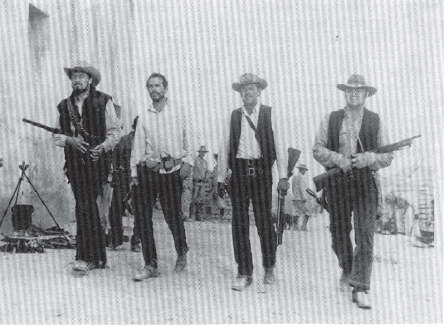

Figure 10.1 |

The Wild Bunch, 1959. ©1959 Warner Bros.-Seven Arts. All Rights Reserved. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Finally, the massacre phase runs 4½ minutes and contains approximately 270 shots, making the average length of a shot 1 second. Some shots run 2 to 3 seconds, particularly when Peckinpah tried to set up a key narrative event, such as the characters who finally kill Pike and Dutch (Ernest Borgnine). Those characters are a young woman and a small boy dressed as a soldier and armed with a rifle.

Few sequences in film history portray the anarchy of violence as vividly as the massacre sequence at the end of The Wild Bunch. Many close-ups are used, the camera moves, the camera is placed very close to the subject, and, where possible, juxtapositions of foreground and background are included. Unlike the opening sequence, where the violence of death seemed to be memorialized in slow motion, the violence of this sequence proceeds less carefully. Chaos and violence are equated with an intensity that wears out the viewer. The resulting emotional exhaustion led Peckinpah to use an epilogue that shifts the point of view from the dead Bishop Pike to the living Deke Thornton. For 5 more minutes, Peckinpah elaborated on the fate of Thornton and the bounty hunters. He also used a reprise to bring back all of the members of the Wild Bunch. Interestingly, all are images of laughter, quite distant from the violence of the massacre.

Rarely in cinema has the potential impact of pace been so powerfully explored as in The Wild Bunch. Peckinpah was interested in the alienation of character from context. His outlaws are men out of their time; 1913 was no longer a time for Western heroes, not even on the American–Mexican border. Peckinpah used pace to create a fascination and later a visual experience of the anarchy of violence. Without these two narrative perspectives—the alienation that comes with modern life and the ensuing violence as two worlds clash—the pace could not have been as deeply affecting as it is in The Wild Bunch.

ALTMAN: THE FREEDOM OF CHAOS

ALTMAN: THE FREEDOM OF CHAOS

Robert Altman is a particularly interesting director whose primary interest is to capture creatively and ironically a sense of modern life. He does not dwell on urban anxiety as Woody Allen does or search for the new altruism à la Sidney Lumet in Serpico (1973) and Prince of the City (1981). Altman uses his films to deconstruct myth (McCabe and Mrs. Miller, 1971) and to capture the ambience of place and time (The Long Goodbye, 1973). He uses a freer editing style to imply that our chaotic times can liberate as well as oppress. To be more specific, Altman uses sound and image editing as well as a looser narrative structure to create an ambience that is both chaotic and liberating. His 1975 film, Nashville, is instructive.

Nashville tells the story of more than 20 characters in a 5-day period in the city of Nashville, a center for country music. A political campaign adds a political dimension to the sociological construct that Altman explores. He jumps freely from the story of a country star in emotional crisis (Ronee Blakley) to a wife in a marriage crisis (Lily Tomlin) and from those who aspire to be stars (Barbara Harris) to those who live off stars (Geraldine Chaplin and Ned Beatty) to those who would exploit stars for political ends (Michael Murphy). Genuine performers (Henry Gibson and Keith Carradine) mix career and everyday life uneasily by reaching an accord between their professional and personal lives.

In the shortened time frame of 5 days in a single city, Nashville, Altman jumped from character to character to focus on their goals, their dreams, and the reality of their lives. The gap between dream and actuality is the fabric of the film. How to maintain continuity given the number of characters is the editing challenge.

The primary editing strategy Altman used in this film was to establish the principle of randomness. Early in the film, whether to introduce a character arriving by airplane or one at work in a recording studio, Altman used a slow editing pace in which he focused on slow movement to catch the characters in action in an ensemble style. Characters speak simultaneously, one in the foreground, another in the background, while responding to an action: a miscue in a recording session, a car accident on the freeway, a fainting spell at the airport. Something visual occurs, and then the ensemble approach allows a cacophony of sound, dialogue, and effects to establish a sense of chaos as we struggle to decide to which character we should try to listen. As we are doing so, the film cuts to another character at the same location.

After we have experienced brief scenes of four characters in a linked location, we begin to follow the randomness of the film. Randomness, rather than pace, shapes how we feel. Instead of the powerful intensity of Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch, we sense the instability that random action and response suggests in Altman's film. The uneasiness grows as we get to know the characters better, and by the time the film ends in chaos and assassination, we have a feeling for the gap between dreams and actuality and where it can lead.

Altman's Nashville is as troubling as Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch, but in Nashville, a random editing style that uses sound as a catalyst leads us to a result similar to that of pace in The Wild Bunch.

Sound itself is insufficient to create the power of Nashville. The ensemble of actors who create individuals is as helpful as the editing pattern. Given its importance to the city, music is another leitmotif that helps create continuity. Finally, the principle of crosscutting, with its implication of meaning arising from the interplay of two scenes, is carried to an extreme, becoming a device that is repeatedly relied upon to create meaning. Together with the randomness of the editing pattern and the overcrowded sound track, crosscutting is used to create meaning in Nashville.

KUBRICK: NEW WORLDS AND OLD

KUBRICK: NEW WORLDS AND OLD

Stanley Kubrick has made films about a wide spectrum of subjects set in very different time periods. Coming as they did in an era of considerable editing panache, Kubrick's editing choices, particularly in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Barry Lyndon (1975), established a style that helped create the sense of the period.

2001: A Space Odyssey begins with the vast expanse of prehistoric time. The prologue proceeds slowly to create a sense of endless time. The images are random and still. Only when the apes appear is there editing continuity, but that continuity is slow and deliberate and not paced for emotional effect. It seems to progress along a line of narrative clarification rather than emotional intensity. When an ape throws a bone into the air, the transition to the age of interplanetary travel is established by a cut on movement from the bone to a space station moving through space.

As we proceed through the story, which speculates on the existence of a deity in outer space, and through the conflict of humanity and machine, the editing is paced to underline the stability of the idea that humanity has conquered nature; at least, they think they have. The careful and elegant cuts on camera movement support this sense of world order. Kubrick's choice of music and its importance in the film also support this sense of order. Indeed, the shape of the entire film more closely resembles the movements of a symphony rather than the acts of a screen narrative.

Only two interventions challenge this sense of mastery. The first is the struggle of HAL the computer to kill the humans on the spaceship. In this struggle, one human survives. The second is the journey beyond Jupiter into infinity. Here, following the monolith, conventional time collapses, and a different type of continuity has to be created.

In the first instance, the struggle with HAL, all the conventions of the struggle between protagonist and antagonist come into play; crosscutting, a paced struggle between HAL and the astronauts leads to the outcome of the struggle, the deaths of four of the astronauts. This struggle relies on many closeups of Bowman (Keir Dullea) and HAL as well as the articulation of the deaths of HAL's four victims. A more traditional editing style prevails in this sequence (Figure 10.2).

In the later sequence, in which the spaceship passes through infinity and Bowman arrives in the future, the traditional editing style is replaced by a series of jump cuts. In rapid succession, Bowman sees himself as a middle-aged man, an old man, and then a dying man. The setting, French Provincial, seems out of place in the space age, but it helps to link the future with the past. As Bowman lies dying in front of the monolith, we are transported into space, and to the strains of “Thus Speak Zarathustra,” Bowman is reborn. We see him as a formed embryo, and as the film ends, the life cycle has come full circle. In Kubrick's view of the future, real time and film time become totally altered. It is this collapse of real time that is Kubrick's greatest achievement in the editing of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Figure 10.2 |

2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968. Copyright Turner Entertainment Company. All Rights Reserved. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Barry Lyndon is based on William Thackeray's novel about a young Irishman who believes that the acquisition of wealth and status will position him for happiness. Sadly, the means he chooses to succeed condemn him to fail. This eighteenth-century morality tale moves from Ireland to the Seven Years War on the continent to Germany and finally to England.

To achieve the feeling of the eighteenth century, it was not enough for Kubrick to film on location. He edited the film to create a sense of time just as he did in 2001. In Barry Lyndon, however, he tried to create a sense of time that was much slower than our present. Indeed, Kubrick set out to pace the film against our expectations (Figure 10.3).1

In the first portion of the film, Redmond Barry (Ryan O'Neal) loves his cousin, Nora, but she chooses to marry an English captain. Barry challenges and defeats the captain in a duel. This event forces him to leave his home; he enlists in the army and fights in Europe.

The first shot of Barry and Nora lasts 32 seconds, the second shot lasts 36 seconds, and the third lasts 46 seconds. When Barry and Nora walk in the woods to discuss her marriage to the captain, the shot is 90 seconds long. By moving the camera and using a zoom lens, Kubrick was able to follow the action rather than rely on the editing. The length of these initial shots slows down our expectations of the pacing of the film and helps the film create its own sense of time: a sense of time that Kubrick deemed appropriate to transport us into a different period from our own. Kubrick used this editing style to re-create that past world. The editing is psychologically as critical as the costumes or the language. In a more subtle way, the editing of Barry Lyndon achieves that other-world quality that was so powerfully captured in 2001.

Figure 10.3 |

Barry Lyndon, 1975. ©1975 Warner Bros. Inc. All Rights Reserved. Still Provided by British Film Institute. |

HERZOG: OTHER WORLDS

HERZOG: OTHER WORLDS

Stanley Kubrick was not alone in using an editing style to create a psychological context for a place or a character. Werner Herzog created a megalomania that requires conquests in Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972). Aguirre the Spanish conquistador is the subject of the film. Even more challenging was Herzog's The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974), the nineteenth-century story about a foundling who, having been kept isolated, has no human communication skills at the onset of the story. He is taken in by townspeople and learns to speak. He becomes a source of admiration and study, but also of ridicule. He is unpredictable, rational, and animistic.

Herzog set out to create an editing style that simulated Kaspar's sense of time and of his struggle with the conventions of his society. Initially, the shots are very long and static. Later, when Kaspar becomes socialized, the shots are shorter, simulating real time. Later, when he has relapses, there are gaps in the logic of the sequencing of the shots that simulate how he feels. Finally, when he dies, the community's sense of time returns. In this film, Herzog succeeded in using editing to reflect the psychology of the lead character just as he did in his earlier film.

In both films, the editing pattern simulates a different world view than our own, giving these films a strange but fascinating quality. They transport us to places we've never before experienced. In so doing, they move us in ways unusual in film.

SCORSESE: THE DRAMATIC DOCUMENT

SCORSESE: THE DRAMATIC DOCUMENT

Martin Scorsese's Raging Bull (1980) is both a film document about Jake LaMotta, a middle-heavyweight boxing champion, and a dramatization of LaMotta's personal and professional lives. The dissonance between realism and psychological insight has rarely been more pronounced, primarily because the character of LaMotta (played by Robert Do Niro) is a man who cannot control his rages. He is a jealous husband, an irrational brother, and a prize fighter who taunts his opponents; he knows no pain, and his scorn for everyone is so profound that it seems miraculous that the man has not killed anyone by the film's end (Figure 10.4).

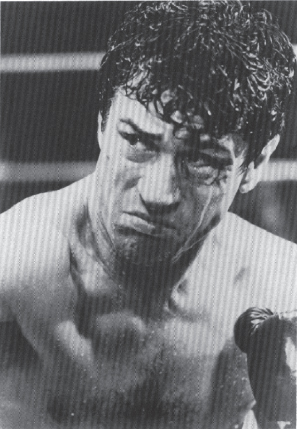

Figure 10.4 |

Raging Bull, 1980. Courtesy MGM/UA. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

That is not to say that the film is not slavish in its sense of actuality and realism. Do Niro, who portrays LaMotta over almost a 20-year period, appears at noticeably different weights. It's difficult to believe that the later LaMotta is portrayed by the same actor as was the early LaMotta.

In the non-fight scenes, Scorsese moved the camera as little as possible. In combination with the excellent set designs, the result is a realistic sense of time and place rather than a stylized sense of time and place.

In the fight sequences, Scorsese raised the dramatic intensity to a level commensurate with LaMotta's will to win at any cost. LaMotta is portrayed as a man whose ego has been set aside; he is all will, and his will is relentless and cruel. This trait is not usually identified with complex, believable characters.

The fight genre has provided many metaphors, including the immigrant's dream in Golden Boy (1939), the existential struggle in The Set-Up (1949), the class struggle in Champion (1949), the American dream in Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), and the American nightmare in Body and Soul (1947). All of these stories have dramatic texture, but none has attempted to take us into the subjective world of a character who must be a champion because if he weren't, he'd be in prison for murder. This is Scorsese's goal in Raging Bull.

To create this world, Scorsese relies very heavily on sound. This is not to say that his visuals are not dynamic. He does use a great deal of camera motion (particularly the smooth handheld motion of a Stedicam), subjective camera placement, and close-ups of the fight in slow motion. However, the sound envelops us in the brutality of the boxing ring. In the ring, the wonderful operatic score gives way to sensory explosions. As we watch a boxer demolished in slow motion, the punches resound as explosions rather than as leather-to-flesh contact.

In the Cerdan fight, in which LaMotta finally wins the championship, image and sound slow and distort to illustrate Cerdan's collapse. In the Robinson fight, in which LaMotta loses his title, sound grinds to a halt as Robinson contemplates his next stroke. LaMotta is all but taunting him, arms down, body against the ropes. As Robinson looks at his prey, the sound drops off and the image becomes almost a freeze frame. Then, as the raised arm comes down on LaMotta, the sound returns, and the graphic explosions of blood and sweat that emanate from the blow give way to the crowd, which cries out in shock. LaMotta is defiant as he loses his title.

By elevating and elaborating the sound effects and by distorting and sharpening the sounds of the fight, Scorsese developed a dramatized envelopment of feeling about the fight, about LaMotta, about violence, and about will as a factor in life.

In a sense, Scorsese followed an editing goal similar to those of Francis Ford Coppola in Apocalypse Now (1979) and David Lynch in Blue Velvet (1986). Each used sound to take us into the interior world of their main characters without censoring that world of its psychic and physical violence. The interior world of LaMotta took Scorsese far from the superficial realism of a real-life main character. Scorsese seems to have acknowledged the surface life of LaMotta while creating and highlighting the primacy of the interior life with a pattern of sound and image that works off the counterpoint of the surface relative to the interior. Because we hear sound before we see the most immediate element to be interpreted, it is the sound editing in Raging Bull that signals the primacy of the interior life of Jake LaMotta over its surface visual triumphs and defeats. The documentary element of the film consequently is secondary in importance to the psychic pain of will, which creates a more lasting view of LaMotta than his transient championship.

WENDERS: MIXING POPULAR AND FINE ART

WENDERS: MIXING POPULAR AND FINE ART

Wim Wenders's Paris, Texas, written by Sam Shepard, demonstrates Wenders's role as a director who chooses a visual style that is related to the visual arts and a narrative style that is related to the popular form sometimes referred to as “the journey.” From The Odyssey to the road pictures of Bob Hope and Bing Crosby, the journey has been a metaphor to which audiences have related.

Wenders used the visual dimension of the story as a nonverbal roadmap to understanding the characters, their relationships, and the confusion of the main character. This nonverbal dimension is not always clear in the narrative.

Because Wenders used a layered approach to the unfolding understanding of his story, pace does not play a major role in the editing of this film. Instead, the visual context is critical to understanding the film's layers of meaning. The foreground-background juxtaposition is the critical factor.

Paris, Texas relates the story of Travis (Harry Dean Stanton), a man we first meet as he wanders through the Texas desert. We soon learn that he deserted his family 4 years earlier. The first part of the film is the journey from Texas to California, where his brother has been taking care of Travis's son, Hunter. The second part concerns the father–son relationship. Although Hunter was four when his parents left him, his knowledge seems to transcend his age. In the last part of the film, Travis and Hunter return to Texas to find Jane (Nastassia Kinski), the wife and mother. In Texas, Travis discovers why he does not have the qualities necessary for family life, and he leaves Hunter in the care of his mother.

A narrative summary can outline the story, but it cannot articulate Travis's ability to understand his world and his place in it. The first image Wenders presents is the juxtaposition of Travis in the desert. The foreground of a midshot of Travis contrasts with visual depth and clarity of the desert. The environment dwarfs Travis, and he seems to have little meaning in this context. Nor is he more at home in Los Angeles. Throughout the film, Travis searches for Paris, Texas, where he thinks he was conceived. Later in the film, when he visits the town, it doesn't shed light on his feelings.

Wenders sets up a series of juxtapositions throughout the film: Travis and his environment, the car and the endless road, and, later, Travis and Jane. In one of the most poignant juxtapositions, Travis visits Jane in a Texas brothel. He speaks to her on a phone, with a one-way mirror separating them. He can look at her, but she cannot see him. In this scene, fantasy and reality are juxtaposed. Jane can be whatever Travis wants her to be. This poignant but ironic image contrasts to their real-life relationship in which she couldn't be what he wanted her to be.

These juxtapositions are further textured by differing light and color in the foreground-background mix. Wenders, working with German cameraman Robbie Muller, fashioned a nether world effect. By strengthening the visual over the narrative meaning of individual images, he created a line somewhere between foreground and background. That line may elucidate the interior crisis of Travis or it may be a boundary beyond which rational meaning is not available. In either case, by using this foreground-background mix, Wenders created a dreamscape out of an externalized, recognizable journey popular in fiction and film. The result is an editing style that deemphasizes direct meaning but implies a feeling of disconnectedness that illustrates well Travis's interior world.

LEE: PACE AND SOCIAL ACTION

LEE: PACE AND SOCIAL ACTION

As a filmmaker, Spike Lee has constantly experimented with narrative convention. In She's Gotta Have It (1986), Lee had the main character address his audience directly. The narrative structure of that film was open-ended and rather more a meditation on relationships than a prescription for relationships. The narrative structure of Mo’ Better Blues (1990) is also meditative but does not parallel the earlier film. Rather its structure approximates the rhythm of a spontaneous blues riff. A film between the two is even more different. The narrative structure of Do the Right Thing (1989) is analogous to an avalanche rushing down a steep mountain. Racial bigotry is the first rock, and the streets of Brooklyn the valley inundated with the inevitable destructive force of the results of that first rock falling.

There is no question that Spike Lee has as his goal to reach first an African-American audience, then an American audience and an international audience. His themes are rooted in the African-American experience, from the interpersonal (Crooklyn, 1994) to the interracial (Jungle Fever, 1991) to the political (Malcolm X, 1992) to the politics of color (School Daze, 1988). He is concerned about man-woman relationships (She's Gotta Have It), about family relationships (Jungle Fever, Crooklyn). Always he is interested in ideology and education, first and foremost in the African-American community (Figures 10.5 and 10.6).

But Lee is also a filmmaker interested in the aesthetic possibilities of visual expression. Although we will focus on his experiments with pace to promote social action, he has also explored the excitement of camera motion (following the character he plays in Malcolm X across the streets of Harlem), the possibilities of slow circular motion in the interview scene in Jungle Fever, and the possibilities of distortion of color using reversal film as the originating material in Clockers (1995). He is always exploring the possibilities of the medium.

The greatest tool, however, that Spike Lee has turned to is pace. Given his agenda for social change, one might anticipate that he would be attratced to pace as he is in Do the Right Thing to raise public ire and anger about racism. Although he uses pace very effectively in that film to promote a sense of outrage, it is actually his other less predictable experiments with pace that make his work so interesting.

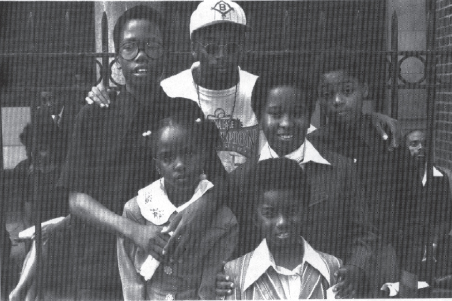

Figure 10.5 |

Crooklyn, 1994. Courtesy Forty Acres and a Mule Filmworks/Spike Lee. |

Figure 10.6 |

Crooklyn, 1994. Courtesy Forty Acres and a Mule Filmworks/Spike Lee. |

Jungle Fever, his exploration of an interracial relationship between an African-American male and an Italian-American female, is notable in how Lee backs away from using pace to create an us-against-them, hero-villain sense in the film (Figure 10.7). In fact, he only resorts to the expected sense of pace around the excitement of the initial sexual encounter of the couple. After that, with family hostility to the relationship growing, we might expect a growing sense of tension with the arc of the interracial relationship. But it doesn't happen. Instead, the tension and consequent use of pace shifts to those around the two lovers. In the Italian community, Angela, the young Italian-American woman (Annabella Sciorra), is beaten by her father upon discovery of the relationship. Pace, as expected, is an important expression of the emotion in the scene. Later, when Angela's spurned boyfriend, Pauly, speaks for tolerance toward the the African-American community, the tension in his soda and newspaper shop is palpable. His customers are intolerant about the new black mayor of New York and Pauly asks politely if they voted. And when he is kind to a young African-American female customer, these same customers are filled with rage and sexual aggression. Pace again plays an important role in the scene.

With regards to the African-American lover (Wesley Snipes), his community also expresses its tension about his new relationship. Whether it is his wife's female friends’ discussions about black men and white women, or his visit to the Taj Mahal crack house to retrieve his parents’ color television from his brother, Gator, in both scenes pace plays an important role to create tension about the potential outcomes of interracial as well as interfamilial relationships.

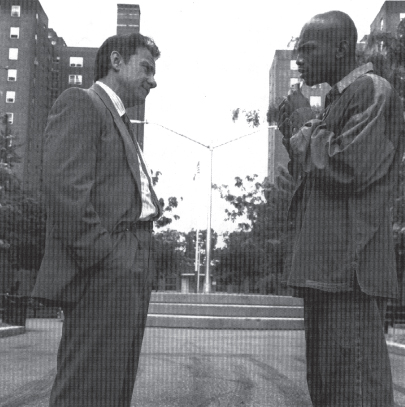

Figure 10.7 |

Jungle Fever, 1991. Copyright ©1991 Universal Studios, Inc. All rights reserved. Courtesy Forty Acres and a Mule Filmworks/Spike Lee. |

In relative terms, the exercise of a slower pace in the scenes between the two lovers creates a sense of reason and tolerance that doesn't exist either in the Italian-American community nor in the African-American community. Although the relationship in the end fails, by using pace in a way that we don't expect, Lee has created a meditation on interracial relationships rather than a prescriptive statement on those relationships.

In Crooklyn, the focus is less on two people than on a family in Brooklyn. And Lee has a different goal in the film—to suggest the strengths of the family and of the community.

Pace can be used to create tension, to deepen the sense of conflict between individuals, families, or communities. Pace can also be used to suggest excitement, energy, power. It is this latter use of pace to which Lee turns in Crooklyn. He wants to suggest the energy and positive force of family and community. The opening fifteen minutes of Crooklyn are instructive here. Children play in the streets adjacent to their home. The day is bright and the feeling is positive. He cuts on movement to make the energy seem more dynamic and positive.

In the home proper, the Carmichael family includes mother (Alfre Woodard), the father (Delroy Lindo), their five children and a dog. The family scenes, whether they are meals together or watching television or sharing news about the future, are energetic and dynamic. The feeling of the scenes is directed by the way Lee uses pace. At times even the chaos seems appealing because of the way pace is used.

These domestic scenes intercut with the less stable elements of the community, strengthen the feeling of the importance of family, of having a mother and a father, even one where the parents have divergent views about discipline.

Throughout the opening scenes, pace is used to affirm a positive, energetic sense of the Carmichael family in the Brooklyn community they are part of. Here, pace is used to underline the values of family so often the sources of tension in Jungle Fever.

Family and its values are also at the heart of the narrative in Clockers (Figures 10.8 and 10.9). Because Clockers is in its form a crime story, in this case the murder of a fast-food manager, we expect the investigation and prosecution of the perpetrator to dictate a particular pace to the film. The expected pace is cut faster as we move to the climax, the exciting apprehension of the perpetrator of the crime. The baptism scene at the end of The Godfather is a classic example of the use of pace to create a sense of climax and release in such a scene.

Lee sidesteps the entire set of expectations we bring to the crime story. Instead he fleshes out the narrative of an African-American family, the eldest son having been accused of the crime; but it is the youngest son in the family, the son deeply involved in the traffic of drugs, who we expect is the real killer, and it is this son who is the focus of the police investigation.

Figure 10.8 |

Clockers, 1995. Courtesy Forty Acres and a Mule Filmworks/Spike Lee. |

In order to discourage his audience from the celebration of violence inherent in the crime film, in order to educate his audience about the real crimes—drugs, mutual exploitation, the increasingly young perpetrators of violent crime in our ghettoes—Lee turns away from pace as a narrative tool. Just as he replaces scenes of characterization for scenes of action, he more slowly cuts those scenes of action when they occur. He also focusses far more on the victims of emotional and physical violence and undermines the potential heroic posture for the perpetrators, the drug king (Delroy Lindo) and the police investigator (Harvey Keitel).

By doing so, Lee risks disappointing his audience, who are accustomed to the fast pace of the crime story. But by doing so, he is pushing into the forefront his educational goals over his entertainment goals. Social action, a new rather than expected action, this is Spike Lee's goal in Clockers. And pace, albeit not as expected, plays an important role in Clockers.

VON TROTTA: FEMINISM AND POLITICS

VON TROTTA: FEMINISM AND POLITICS

In the 1970s, Margarethe von Trotta distinguished herself as a screenwriter on a series of films directed by her husband, Volker Schlondorff. They codirected the film adaptation of the Henrich Böll novel, The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (1975). In 1977, von Trotta began her career as a writerdirector with The Second Awakening of Crista Klages.

Figure 10.9 |

Clockers, 1995. Courtesy Forty Acres and a Mule Filmworks/Spike Lee. |

All of her work as a director is centered on female characters attempting to understand and act upon their environment. Von Trotta is interesting in her attempt to find a narrative style suitable to her work as an artist, a feminist, and a woman. As a result, her work is highly political in subject matter, and when compared to the dominant male approach to narrative and to editing choices, von Trotta appears to be searching for alternatives, particularly narrative alternatives. Before examining Marianne and Julianne (1982), it is useful to examine von Trotta's efforts in the light of earlier female directors.

In the generation that preceded von Trotta, few female directors worked. Two Italians who captured international attention were Lina Wertmüller and Liliana Cavani. Wertmüller (Swept Away-.-.-.-, 1975; Seven Beauties, 1976) embraced a satiric style that did not stand out as the work of a woman. Her work centered on male central characters, and in terms of subject—malefemale relationships, class conflicts, regional conflicts—her point of view usually reflected that of the Italian male. In this sense, her films do not differ in tone or narrative style from the earlier style of Pietro Germi (Divorce—Italian Style, 1962).

Liliana Cavani (The Night Porter, 1974) did make films with female central characters, but her operatic style owed more to Luchino Visconti than to a feminist sensibility. If Wertmüller was concerned with male sexuality and identity, Cavani was concerned with female sexuality and identity.

Before Wertmüller and Cavani, there were few female directors. However, Leni Riefenstahl's experimentation in Olympia (1938) does suggest an effort to move away from a linear pattern of storytelling.

Although generalization has its dangers, a number of observations about contemporary narrative style set von Trotta's work in context in another way. There is little question that filmmaking is a male-dominated art form and industry, and there is little question that film narratives unfold in a pattern that implies cause and effect. The result is an editing pattern that tries to clarify narrative causation and create emotion from characters’ efforts to resolve their problems.

What of the filmmaker who is not interested in the cause and effect of a linear narrative? What of the filmmaker who adopts a more tentative position and wishes to understand a political event or a personal relationship? What of the filmmaker who doesn't believe in closure in the classic narrative sense?

This is how we have to consider the work of Margarethe von Trotta. It's not so much that she reacted against the classic narrative conventions. Instead, she tried to reach her audience using an approach suitable to her goals, and these goals seem to be very different from those of maledominated narrative conventions.

It may be useful to try to construct a feminist narrative model that does not conform to classic conventions, but rather has different goals and adopts different means. That model could be developed using recent feminist writing. Particularly useful is the book, Women's Way of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice and Mind.2 Mary Field Belenky and her coauthors suggest that women “that are less inclined to see themselves as separate from the ‘theys’ than are men, may also be accounted for by women's rootedness in a sense of connection and men's emphasis on separation and autonomy.”3 In comparing the development of an inner voice in women to that of men, the authors suggest the following: “These women reveal that their epistemology has shifted away from an earlier assumption of ‘truth from above’ to a belief in multiple personal truths. The form that multiplicity (subjectivism) takes in these women, however, is not at all the masculine assertion that ‘I have the right to my opinion;’ rather, it is the modest inoffensive statement, ‘it's just my opinion.’ Their intent is to communicate to others the limits, not the power, of their own opinions, perhaps because they want to preserve their attachments to others, not dislodge them.”4 The search for connectedness and the articulation of the limits of individual efforts and opinions can be worked into an interpretation of Marianne and Julianne.

Marianne and Julianne are sisters. The older sister, Julianne, is a feminist writer who has devoted her life to living by her principles. Even her decision not to have a child is a political decision. Marianne has taken political action to another kind of logical conclusion: She has become a terrorist. In the film, Von Trotta was primarily concerned by the nature of their relationship. She used a narrative approach that collapses real time. The film moves back and forth between their current lives and particular points in their childhoods. Ironically, Julianne was the rebellious teenager, and Marianne, the future terrorist, was compliant and coquettish.

The contemporary scenes revolve around a series of encounters between the sisters; Marianne's son and Julianne's lover take secondary positions to this central relationship. Indeed, the nature of the relationship seems to be the subject of the film. Not even Marianne's suicide in jail slows down Julianne's effort to confirm the central importance of their relationship in her life.

Generally, the narrative unfolds in terms of the progression of the relationship from one point in time to another. Although von Trotta's story begins in the present, we are not certain how much time has elapsed by the end. Nor does the story end in a climactic sense with the death of Marianne.

Instead, von Trotta constructed the film as a series of concentric circles with the relationship at the center. Each scene, as it unfolds, confirms the importance of the relationship but does not necessarily yield insight into it. Instead, a complex web of emotion, past traumas, and victories is constructed, blending with moments of current exchange of feelings between the sisters. Intense anger and love blend to leave us with the sense of the emotional complexity of the relationship and to allude to the sisters’ choice to cut themselves off emotionally from their parents and, implicitly, from all significant others.

As the circles unfold, the emotion grows, as does the connection between the sisters. However, limits are always present in the lives of the sisters: the limits of social and political responsibility, the limits of emotional capacity to save each other or anyone else from their fate. When the film ends with the image of Julianne trying to care for Marianne's son, there is no resolution, only the will to carry on.

The film does not yield the sense of satisfaction that is generally present in classic narrative. Instead, we are left with anxiety for Julianne's fate and sorrow for the many losses she has endured. We are also left with a powerful feeling for her relationship with Marianne.

Whether von Trotta's work is genuinely a feminist narrative form is an issue that scholars might take up. Certainly, the work of other female directors in the 1980s suggests that many in the past 10 years have gravitated toward an alternative narrative style that requires a different attitude to the traditions of classical editing.

FEMINISM AND ANTINARRATIVE EDITING

FEMINISM AND ANTINARRATIVE EDITING

Although some female directors have chosen subject matter and an editing style similar to those of male directors,5 there are a number who, like von Trotta, have consciously differentiated themselves from the male conventions in the genres in which they choose to work.

For example, Amy Heckerling has directed a teenage comedy from a girl's perspective. Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) breaks many of the stereotypes of the genre, particularly the attitudes about sex roles and sexuality.

Another film that challenges the conventional view of sex roles and sexuality is Susan Seidelman's Desperately Seeking Susan (1985). The narrative editing style of this film emulates the confusion of the main character (Rosanna Arquette). Seidelman was more successful in using a nonlinear editing pattern than was Heckerling, and the result is an originality unusual in mainstream American filmmaking.

Outside of the mainstream, Lizzie Borden created an antinarrative in Working Girls (1973), her film about a day in the life of a prostitute. Although the subject matter lends itself to emotional exploitation, as illustrated by Ken Russell's version of the same story in Whore (1991), Borden decided to work against conventional expectations.

She focused on the banality of working in a bordello, the mundane conversation, the contrast of the owner's concerns and the employees’ goals, and the artifice of selling the commodity of sex. Borden edited the film slowly, contrary to our expectations. She avoided close-ups, preferring to present the film in mid- to long shots, and she avoided camera motion whenever possible. As a result, the film works against our expectation, focusing on the ironic title and downplaying the means of their livelihood. Borden concentrated on the similarities of her characters’ lives to those of other working women.

Another antinarrative approach adopted by women directors is to undermine the notion of a single voice, that of the main character in the narrative. Traditionally, the main character is the dramatic vehicle for the point of view, the point of empathy and the point of identification. By sidestepping a single point of view, the traditional arc of the narrative is undermined. Two specific examples will illustrate.

Agnieszka Holland was already established as a director who explored new narrative approaches (she uses a mixed genre approach in her film Europa, Europa [1991]; see next section on mixing genres) when she made Olivier, Olivier (1992).

Olivier, Olivier is a story about a family tragedy. In rural France, a middleclass family has two children, an older daughter and a young son. The boy is clearly the focal point of the family for the mother. The older sibling is ignored. She is also the family member who doesn't quite fit in, a role that often evolves into the scapegoat in family dynamics. One day, the young boy is sent off to deliver lunch to his father's mother. He never returns. In spite of extensive investigation, there is no trace of the boy. The family disintegrates. The local detective is transferred to Paris, determined not to give up on the case. Six years later, he finds a street kid, aged 15, who looks like the disappeared Olivier. He is certain he has found the boy. So is the mother. Only the sister is suspicious. The father, who had left the family to work in Africa, returns. Just as Olivier returns, the family seems to heal, to be whole again. The mother, who had all but fallen apart and blamed the father for Olivier's disappearance, for the first time in years is happy.

The new Olivier seems happy, eccentric, but not poorly adjusted given his trauma. He wants to be part of this family. But one day he discovers the neighbor molesting a young boy and when the police are called, Olivier confesses that he is not the original Olivier and the killer admits to killing the original Olivier. What is to happen to this family who have already endured so much tragedy? Will they relive the original tragedy with all its profound loss? Or will the mother deny again the loss and try for a new life with the new Olivier?

What is interesting about Holland's narrative approach is that she does not privilege any one character over any other. The story presents the point of view of the mother, the father, the sister, Olivier, the new Olivier.

If Holland had chosen a single point of view, a sense of resolution might have resulted in the discovery of the fate of Olivier. Without a single point of view, we have far less certainty. Indeed we are left totally stranded in this family tragedy. And the consequence is a profound shock at the end of Olivier, Olivier. This is the direct result of the multiple perspectives Holland has chosen.

Julie Dash follows a singular narrative path in her film Daughters of the Dust (1991). However her purpose is quite different from Agnieszka Holland. Whereas Holland is looking to destabilize our identification with the multiple points of view in Olivier, Olivier, Julie Dash wants to stabilize and generalize the point of view: the multiple perspectives together represent the African-American diaspora experience in the most positive light.

Daughters in the Dust takes place in a single summer day in 1902, in the Sea Islands of the South. Those Sea Islands are off the coast of South Carolina and Georgia. On the islands, life has become a hybrid, not African and not American. The elderly matriarch of the family will stay behind, but she has encouraged her children to go north to the mainland to make a life. She has also told them not to forget who they are. She will remain to die in her home at Ibo Landing.

Julie Dash deals with the feelings that surround this leavetaking with the points of view of the matriarch, her daughters, a niece from the mainland (called Yellow Mary), and an unborn granddaughter who narrates the beginning and end of the story. No single voice is privileged over any other.

The conflicts around behavior—a granddaughter has been impregnated via a rape, Yellow Mary may have made her way on the mainland through prostitution, a granddaughter has an Indian-American lover with whom she may want to remain on the island—all dim next to the conflictual future these migrants may face when they move north.

In order to create a sense of tolerance and power in the women, Dash presents the men as the weaker, more emotional sex. She also empowers a matriarch as the focal center of the life of the entire family. By doing so, she diminishes the sense of tension and conflict among the women and emphasizes their collective power and stability. Together they are the family and the purveyors of continuity for the family. And by giving one of the voices—the unborn child—the privileged position of early and closing narrator, Dash frames a voice for the future. But even that voice depends for life on the continuity of family.

Consequently in Daughters in the Dust, Julie Dash uses multiple points of view to sidestep linearity and to instead emphasize the circularity of the life cycle. It is strong, stable, and ongoing.

Although these directors did not proceed to a pattern of circular narrative as von Trotta did, there is no question that each is working against the conventions of the narrative tradition.

MIXING GENRES

MIXING GENRES

Since the 1980s, writers and directors have been experimenting with mixing genres. Each genre represents particular conventions for editing. For example, the horror genre relies on a high degree of stylization, using subjective camera placement and motion. Because of the nature of the subject matter, pace is important. Although film noir also highlights the world of the nightmare, it tends to rely less on movement and pace. Indeed, film noir tends to be even more stylized and more abstract than the horror genre. Each genre relies on visual composition and pace in different ways. As a result, audiences have particular emotional expectations when viewing a film from a particular genre.

When two genres are mixed in one film, each genre brings along its conventions. This can sometimes make an old story seem fresh. However, the results for editing of these two sets of conventions can be surprising. At times, the films are more effective, but at other times, they simply confuse the audience. Because the mixed-genre film has become an important new narrative convention, its implications for editing must be considered.

There were numerous important mixed-genre films in the 1980s, including Jean-Jacques Beineix's Diva (1982) and Joel Coen's Raising Arizona (1987), but the focus here is on three: Jonathan Demme's Something Wild (1986), David Lynch's Blue Velvet, and Errol Morris's The Thin Blue Line (1988).

Something Wild is a mix of screwball comedy and film noir. The film, about a stockbroker who is picked up by an attractive woman, is the shifting story of the urban dream (love) and the urban nightmare (death).

Screwball comedies tend to be rapidly paced, kinetic expressions of confusion. Film noir, on the other hand, is slower, more deliberate, and more stylized. Both genres focus sometimes on love relationships.

The pace of the first part of Something Wild raises our expectations for the experience of the film. The energy of the screwball comedy, however, gives way to a slower-paced dance of death in the second half of the film. Despite the subject matter, the second half seems anticlimactic. The mixed genres work against one another, and the result is less than the sum of the parts.

David Lynch mixed film noir with the horror film in Blue Velvet. He relied on camera placement for the identification that is central to the horror film, and he relied on sound to articulate the emotional continuity of the movie. In fact, he used sound effects the way most filmmakers use music, to help the audience understand the emotional state of the character and, consequently, their own emotional states.

Lynch allowed the sound and the subjectivity that is crucial in the horror genre to dominate the stylization and pacing of the film. As a result, Blue Velvet is less stylized and less cerebral than the typical film noir work. Lynch's experiment in mixed genre is very effective. The story seems new and different, but its impact is similar to such conventional horror films as William Friedkin's The Exorcist (1973) or David Cronenberg's Dead Ringers (1988).

Errol Morris mixed the documentary and the police story (the gangster film or thriller) in The Thin Blue Line, which tells the story of a man wrongly accused of murder in Texas. The documentary was edited for narrative clarity in building a credible case. With clarity and credibility as the goals of the editing, the details of the case had to be presented in careful sequence so that the audience would be convinced of the character's innocence. It is not necessary to like or identify with him. The credible evidence persuades us of the merits of his cause. The result can be dynamic, exciting, and always emotional.

Morris dramatized the murder of the policeman, the crime that has landed the accused in jail. The killing is presented in a dynamic, detailed way. It is both a shock and an exciting event. In contrast to the documentary film style, many close-ups are used. This sequence, which was repeated in the film, was cut to Phillip Glass's musical score, making the scene evocative and powerful. It is so different from the rest of the film that it seems out of place. Nevertheless, Morris used it to remind us forcefully that this is a documentary about murder and about the manipulation of the accused man.

The Thin Blue Line works as a mixed-genre film because of Glass's musical score and because Morris made clear the goal of the film: to prove that the accused is innocent.

Mixing genres is a relatively new phenomenon, but it does offer filmmakers alternatives to narrative conventions. However, it is critical to understand which editing styles, when put together, are greater than the sum of their parts and which, when put together, are not.