The Script: Option and Development

TIME TO DO THE PAPERWORK

Let’s get a few things straight right away. You may be thinking, “I don’t really need to read this part because I am optioning my friend’s script.” Or you are saying, “It’s my sister’s script, for heaven’s sake; I’m not going to ask her to sign an option, she’s family.” I don’t care whose script it is – you have to do the paperwork. It’s a business, right? Do the paperwork. Also, people can get really weird about their baby, “the screenplay.” I made that mistake early on with a very close friend of mine. She was the nicest, sweetest woman – very trustworthy. The minute we started to get solid interest in the script from some of the big production companies, the writer wanted the moon – extremely unreasonable and unrealistic. We had to walk away from the project and attempt to scrape the egg off our faces. If we had signed an option agreement with her and made certain that everything was clear on paper first, none of that would have happened.

As I mentioned in my introduction, my friend John called me from the Cannes Film Market and said that a distributor was interested in the selling and distribution of his film. He was overjoyed until he called the writer and she told him that because she and the director had had a falling out “there wasn’t a chance in hell she was going to sign the option.” When I asked him why he hadn’t had her sign the option agreement at the beginning, he said that the writer was his friend, and why do the paperwork if it’s your friend? As bad as I felt for him, the fact is that he had failed to address the business part of the business and get everything signed off on before moving ahead.

RESEARCH AND READ OPTION AGREEMENTS

When it comes to option agreements, please do your research and read a few of them to get educated as to what is required. There are many templates out there in books and online. I know that when you are doing a low-budget film, you will not have money to pay for an attorney to create the option, deal memo, contracts, and other items that you will need for your film. However, what I do is research the ones that are already out there and get copies of other producers’ option agreements and deal memos and then take the best of all of them. Then I create my own versions and give them to an attorney to make sure they cover everything that needs to be covered. Better to pay for that one or two hours of the attorney’s time than to hire him or her to do an entire deal memo.

On my bigger films, I always have attorney fees in the budget, but at the SAG ultra-low level it just isn’t possible to pay for an attorney to create your option agreement and all necessary deal memos from scratch. This was a perfect alternative, and I was able to get a lot more educated on deal memos and contracts along the way, which I feel as a producer is of critical importance. Even if you have a great attorney, please read every deal memo that you will be signing off on. Ultimately, it is your responsibility.

WHAT’S NEEDED IN AN OPTION/PURCHASE AGREEMENT

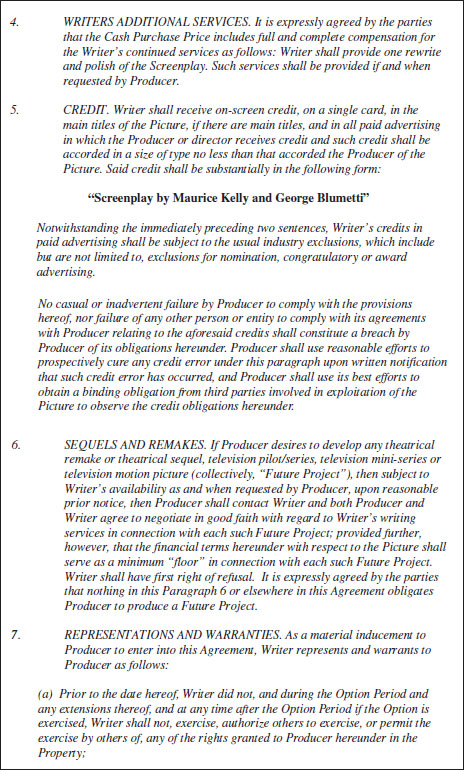

My option/purchase agreement covers all the necessary legal points. Most are self-explanatory, but I will explain briefly those areas that might be confusing, and I’ve provided an example of an actual option/purchase agreement later in this section. But first, here’s what it must cover:

1. Underlying rights option/purchase agreement.

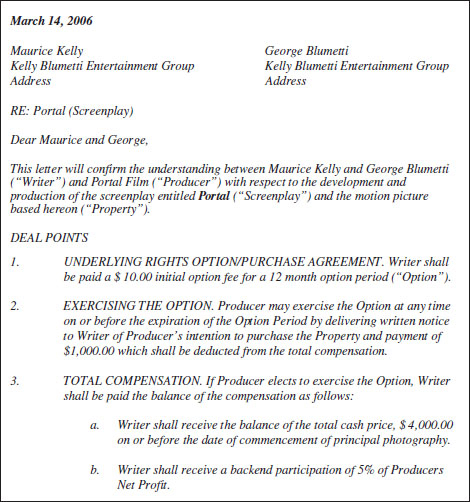

2. Exercising the option. Here is the wording from the option agreement on Portal: “Producer may exercise the Option at any time on or before the expiration of the Option Period by delivering written notice to Writer of Producer’s intention to purchase the Property and payment of $1,000.00, which shall be deducted from the total compensation.” As you can see, we were able to exercise the option with a portion of the purchase price. However, there are other times when Kate and I exercise the option with the full purchase price. If you are dealing with a guild writer, you need to exercise with the full purchase price. “Exercising the option” simply means that the rights for the project transfer directly to you the producer.

3. Total compensation.

4. Writers’ additional services.

6. Sequels and remakes

7. Representations and warranties. This section explains that the writer is the sole and exclusive author of the property and that the writer owns the sole and exclusive rights, title and interest in and to the property, free and clear of any right, claim, lien, title, or interest of any third party.

8. No obligation to use services and proceeds. This part of the agreement explains how the producer is not obligated to use all or any portion of the screenplay or the results and proceeds of writer’s services.

9. Assignment. This section gives the producer the unrestricted right to assign, license, delegate, or otherwise transfer and convey this agreement to any firm, corporation, partnership, or entity for the express purpose of further developing and/or producing the picture.

10. Ownership of rights and services. This section is quite a long paragraph but is very important because it greatly protects the producer. Briefly, it states that the writer agrees that in the event the producer properly exercises the option, the producer shall automatically become the sole and exclusive worldwide owner of all rights, titles, and interest in the work.

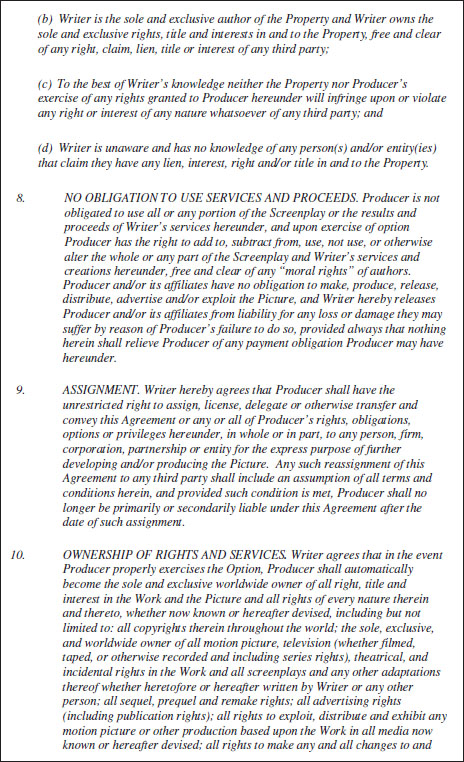

11. Joint and several obligations. This section explains that all benefits and obligations shall be the joint obligations of each of the producers and each of the writers.

12. Notices. This section simply states that all notices and payments pursuant to this agreement must be in writing and sent to the appropriate party at the address set forth below.

13. Claims/liability. This section is used in every agreement I have ever seen; it basically states that once the writer is paid the purchase price, the writer shall not in any way constitute or give rise to the writer having a lien or claim upon the picture.

14. Indemnification. This section is a crucial point because it states that the writer indemnifies the producer and the producer indemnifies the writer. They agree to hold each other harmless from and against any and all claims, liabilities, and causes of action arising out of a material breach.

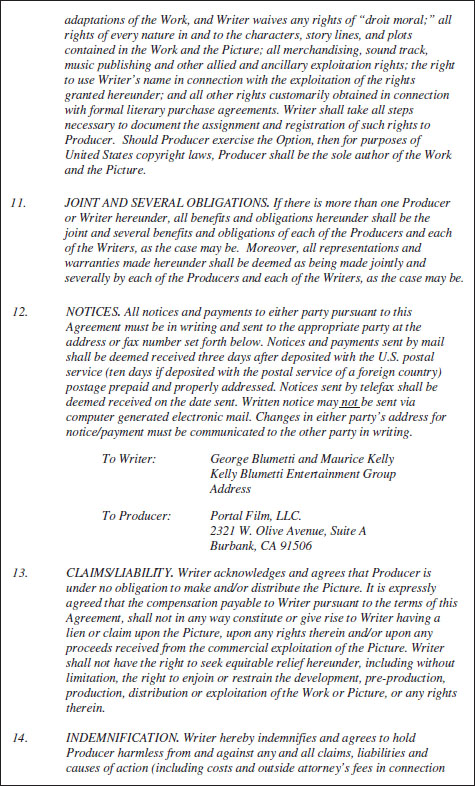

15. Choice of law and jurisdiction.

16. No partnership or joint venture. This section points out that the agreement does not constitute either party the agent of the other, or create a partnership or joint venture between the parties.

17. Entire agreement. This section is already fairly clear. It states that this agreement contains the full and complete understanding between the parties with regard to the subject matter and cannot be modified or amended except by a written instrument signed by each party.

18. Capacity to contract. This section refers to the fact that both the writer and producer represent and warrant that they have full power and authority to enter into this agreement.

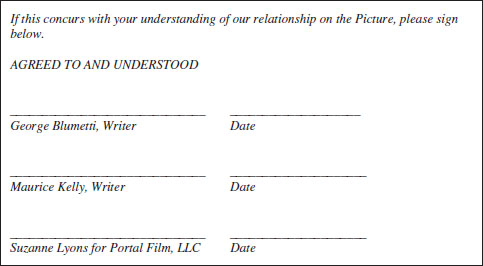

Do some research on option agreements and look at a few of them before choosing a template that works for you. Then, please, once you have put yours together, have an entertainment attorney read it over. Figure 3.1 shows the agreement that we used on Portal.

FIGURE 3.1

OPTION PERIOD

In the three ultra-low-budget films (each costing around $200,000) we produced and the one we executive-produced, Kate and I knew we were going to be shooting within six to eight months of the initial option agreement date, so our options were for a twelve-month period. But in cases where we were optioning a project to pitch to the studios or to put together as a Canadian/UK coproduction, those options were eighteen months. In most cases, our option agreements were twelve months with an automatic six-month extension if we had certain elements attached. Because Kate and I offer only $10 for the option, we really tried to keep our agreement within the eighteen-month period and to work as quickly and effectively as possible, creating urgency with each phone call we made.

PAYMENT AND BACK END

At the SAG ultra-low-budget level, we offered the writer $10 for the option and $5,000 for the price of the screenplay. We paid $1,000 the first day of preproduction so that we could start the paperwork on the copyright transfer, and then we paid the final $4,000 on the first day of principal photography. We offered a percentage of the producer’s net profits, but at this budget it’s not necessary. Many times, at this budget level, it is a first-time writer and a first-time director who are getting the chance to see their dream of having their film produced. Your writer and director are getting a DVD. It’s really like giving them a check for $200,000! It’s their showpiece. And if it is a success, it is the writer and the director who will get the recognition. The agents and studios will be knocking on their doors.

You, as the producer, will be spending nearly two years (and beyond!) producing the film and your salary in the budget will no doubt be much less than $5,000. After having gone through the last few years producing these films, I believe that as much of the back end as possible (if there is any at all) should go to the producer. If there is any money coming in, this may be the only way you recoup your costs. If you think you want to share part of the producer’s net profit, then offer a small percentage to the writer and director. However, if their name is helping you sell the units for your film or will help in the selling of your film to distributors, like your lead actor’s name would, then that is different. That is worth some points on the back end.

DEFERMENTS

I try to avoid deferments at this budget level. It would be a pain to say to the investors when the first check comes in from a territory sale, “Oh, sorry, but I have deferments to the writer, director, and cast to make first.” Kate and I had to do it only once on our low-budget films. I hear producers touting it all the time and I really don’t get it. People talk about deferments as if they are not an issue, but they are. Personally, I don’t think it’s fair to the investors. When the money starts to come in, you want it to go the investors. You don’t want a long list of cast and crew who are still owed money that you deferred. Keep it clean and simple. You know your budget, raise the money, and pay people during production. Everyone got paid on our films and everyone was happy.

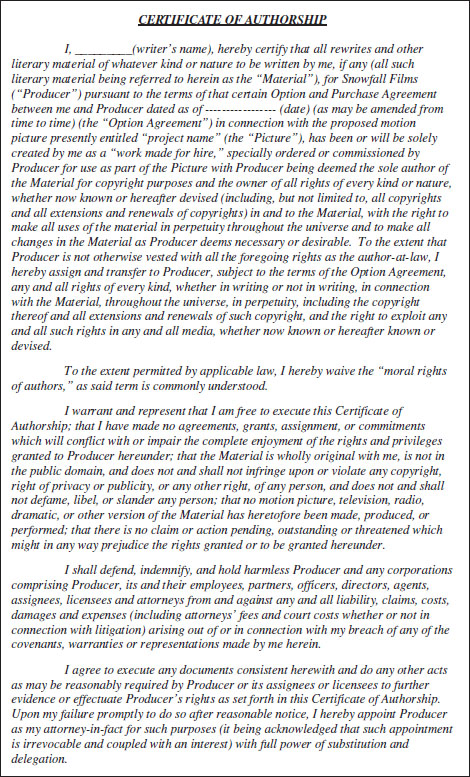

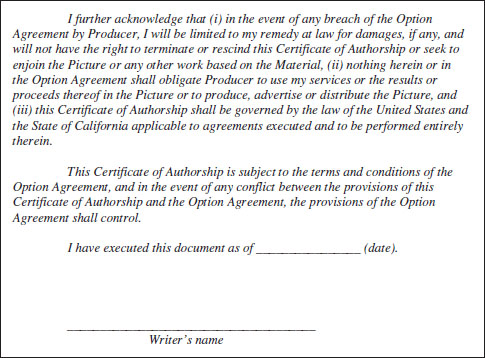

CERTIFICATE OF AUTHORSHIP AND SHORT-FORM ASSIGNMENT

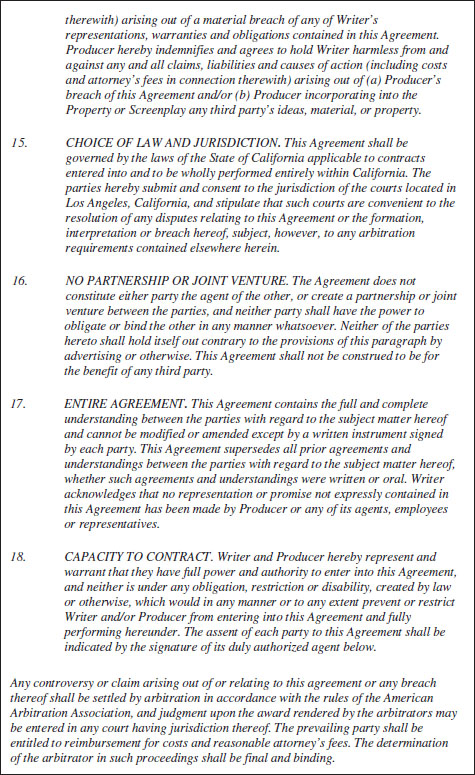

I always make a point of attaching two additional pieces to the option agreement, the certificate of authorship and the short-form assignment. The certificate of authorship states that the writer is the sole writer of the screenplay and that the writer has to sign his or her name to that effect. Figure 3.2 shows a sample copy that I use in my workshop.

Figure 3.2

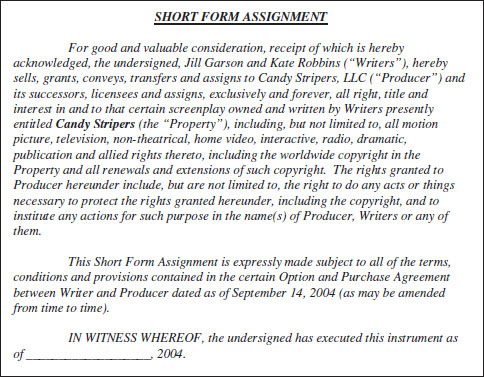

The short-form assignment states that the writer gives you, the producer, the right to transfer the copyright when you have paid the full purchase price for the screenplay. It literally transfers the rights of the author and grants those rights to the assignee as if they were the author in perpetuity. I have looked at many templates for option agreements, and seldom do I see this short form agreement attached to it. I had a friend tell me about one of his early films on which he didn’t know about the short-form agreement and thought the option agreement was sufficient. When it came time to transfer the rights and fill out the copyright paperwork, he needed the short-form assignment signed by the writer to allow him the right to do the transfer, and the writer refused to sign it unless he was paid an additional $10,000! No chain of title, no movie! It’s that simple.

Figure 3.3 shows a copy of the short-form assignment for Candy Stripers.

Figure 3.3

SCRIPT DEVELOPMENT

Once you have the option/purchase agreement, it’s time to move to the next step: script development. It’s common practice that option agreements state that the writer will provide a rewrite and polish. Note that I am not talking about Writer’s Guild agreements. Guild agreements are different; at this budget level, for the most part, you are not dealing with Guild writers. However, if you are, please speak with the Guild in your country about rewrites and polishes. Whether you are going to the studio to pitch it as a bigger budget film or planning to go the low-budget indie route and raise the funds to shoot it yourself, you want the best possible script.

TABLE READ

I strongly suggest that you do a table read. It’s free, and you can always have one of your actor friends manage it for you. Have the writer present and the director (if you have a director at this point). There is nothing like hearing the script read aloud to really give you and the writer a clear sense of the story, what can be changed to make it better and what can be cut to make it shorter and more budget-friendly. At the $200,000 budget, 90 to 95 pages is a great length.

Candy Stripers started at 115 pages with more than 60 speaking roles. During the table read, we could see where it could be cut to fit our budget without compromising the integrity of the story.

DIRECTOR’S NOTES

If you have your director on board at this point, he or she will have brilliant suggestions as well. However, many times, at this low budget level, you will have a first-time director, so you – as the producer, knowing your budget level – will have to oversee the rewrite and script changes to ensure that it can be done for the budget you have in mind. On the bigger-budget projects, it is customary for the director to have a much bigger say with regard to the rewrite and direction that the screenplay will take. Film is a director’s medium, and it will be his or her vision on the screen. However, at the SAG ultra-low budget level, you – the producer – must work closely with the director and writer. At this budget level, you will have to monitor the changes to ensure they fit the budget. Your director is going to want things that at this budget, you cannot provide. Everyone – the writer, the director, the DP, and the keys – all must be flexible and reasonable, perhaps even willing to push their creative boundaries. Maybe you can’t afford that crane for the day, so what are some alternative ways to shoot that scene that will be even more interesting, unique, and artistic?

Get the screenplay as perfect as you possibly can during the development stage. Of course, there will be changes as you move along, but really work to get it where you want it so that you can be confident that your line producer can sign off on the budget you are committed to having.