05

“The cautious seldom err.”

Confucius“What’s the worst that could happen?”

Advertising slogan for Dr Pepper

Time to use your mind’s eye. I want you to think about your favourite snack. What do you like to treat yourself with? Perhaps it’s a bar of chocolate, a bacon sandwich, a tub of ice cream. A slab of cake, a portion of fish and chips, a bag of popcorn. Mmm … Whatever it is, I want you to imagine that you have it in front of you right now.

OK, now imagine that you have a short piece of work to do – it’ll take you about 20 minutes to complete. You now have two choices. You can either enjoy your snack now and then start the work. Or finish the work first and reward yourself with the snack afterwards. Which would you choose?

That simple choice illustrates the two ends of the Conscientiousness spectrum. High-Conscientiousness people control their impulses. They are disciplined, organised and self-controlled. Low-Conscientiousness people happily follow their impulses and are spontaneous, fun-loving and adventurous.

There are advantages and disadvantages to both. High-Conscientiousness individuals are careful and hardly ever make mistakes, but can sometimes be too conservative, too risk-averse. Low-Conscientiousness individuals are adaptable and flexible, but can drive people crazy for being disorganised and taking too many risks.

Time to see how you measure up.

Your Conscientiousness

Questionnaire 4 on page 10 measures your Conscientiousness. Score two points each time you agreed with any of the following statements: 1, 3, 4, 7 and 9. Give yourself two points each time you disagreed with any of the statements: 2, 5, 6, 8 and 10. You should have a total score between 0 and 20.

A score of 8 or less suggests low levels of Conscientiousness. A score of 14 or more means that you have high levels of Conscientiousness. A score of 10 or 12 means that you have average levels of Conscientiousness.

Time to read the sections that are aimed at your personality profile. If you’re average for Conscientiousness, you could probably do with being a bit more prudent, so focus on the advice within the Low-Conscientiousness sections. If you’re high for Conscientiousness, learn to let go a little more.

What kind of person are you?

You can spot a child’s level of Conscientiousness from as young as four years of age. Stanford University professor Walter Mischel brought four-year-olds into a room one by one and put a marshmallow on the table in front of them. He told the kids, ‘You can eat this marshmallow right now if you like. But, if you can wait while I leave the room for a few minutes, you can have two marshmallows when I return.’

About a third of the kids ate the marshmallow straight away. Another third waited 20 minutes to receive two marshmallows. The remaining third of the children waited for a little while, but ultimately gave up and succumbed to the temptation of the single marshmallow in front of them.

The Low-Conscientiousness person: the swashbuckling opportunist

As a kid, you would have been one of those who ate the marshmallow pretty quickly because you’re someone who lives for the here and now.

You’re a flexible, adaptable person who enjoys dynamic, changing situations. Others may prefer the routine of a conventional 9 to 5 existence, of having a job that is the same day in, day out. But that would bore you stupid. While others hate uncertainty, you thrive on living in the moment, not knowing what might happen from one day to the next.

In your personal life too, you dislike being tied down by plans. Others may want to schedule ahead for weeks and months in advance, but you don’t want to have every evening and weekend mapped out for the foreseeable future. Whatever happened to spontaneity?

You may get infuriated by ‘paralysis analysis’, by people who sit on the sidelines endlessly debating the right thing to do. If you spot an opportunity, you’d rather give it a go and see what comes off. Carpe diem. Seize the day. If you had to pick a modern-day slogan, perhaps you’d choose Nike’s ‘Just Do It’. Clichés, of course, but you feel that life is too short to watch it pass by.

And if something goes wrong, you’re adaptable. You’ll survive. You’ll respond to the needs of the moment. You’ll change tactics and try it another way. Better to learn from what you did than regret what you didn’t do.

You find rules and red tape tedious. You feel that the ends justify the means. So rather than follow overly restrictive rules that stop you from achieving your goals, you’re happy to bend them.

And don’t get you started on filling in forms and doing paperwork. You understand that some of the books need keeping. But in an ideal world, you’d do away with all of that needless, yawnsome bureaucracy.

You’re happy to take risks. You embrace change. You think on your feet. All qualities that serve you well in a furiously paced and ever-changing world.

The High-Conscientiousness person: the good organisational citizen

As a child, you would have been happy to wait to get that second marshmallow. Because you’re patient and the kind of person who thinks before acting.

You’re a trustworthy, dependable, organised person. Others may be impetuous, erratic or forgetful, but not you. Friends rely on your incredible ability to get things done – to keep track of important dates, pick up tickets, make dinner reservations, find the best deals. Colleagues envy your ability to keep on top of everything. You always deliver; you’re a safe pair of hands.

You set high standards for yourself and others. You have a good level of attention to detail and you make few mistakes. That’s because you take the time to gather the facts, weigh up the pros and cons, and make a reasoned decision. Fools rush in, don’t they?

The world is full of traps and pitfalls that can befall the unwary – anything from forgetting to pack your passport before leaving for the airport to leaving a report until the last minute. But those kinds of things don’t happen to you. You identify what needs doing. You make lists, weigh up options and leave little to chance.

In fact, your natural instinct is to impose order on your environment. You may not necessarily be neat and tidy, but you prefer to reduce unpredictability by making plans. You control, manage and orchestrate the world around you. If something could go wrong, you’d rather have considered the contingency and be ready for it than simply hope it won’t happen. Better safe than sorry.

You respect the rules of the game too. Rules are there for a reason. Whether in your work life or your home life, you like to know what is acceptable and what is out of bounds.

You’re careful. You can be trusted. You never let people down. All qualities that make you a loyal friend and exemplary organisational citizen.

Make the most of yourself – for Low-Conscientiousness people

Let’s get one thing straight. You will never be great at dotting the ‘i’s and crossing the ‘t’s. Following strict rules and guidelines, focusing constantly on detail, and repeating routines over and over again taps into all of your weak spots. So why do it?

Play to your strengths, not your weaknesses

You will do well in entrepreneurial settings and creative jobs where breaking the rules, challenging the status quo and even shocking people occasionally are considered positive outcomes.

Avoid large organisations with time-honoured traditions where the way of doing things is, has been and always will be the same. To thrive, you must find environments in which you can capitalise on your strong points.

That’s not to say that you can get away with flouting every rule. There are some rules that must be obeyed if you don’t want to crash and burn. Perhaps for reasons of health and safety – to avoid lives or limbs being in jeopardy. Or so you don’t risk big fines from a regulator. The bosses at Enron, the US business that combusted so spectacularly back in 2001, provide a great example of what can happen when Low-Conscientiousness people are so focused on achieving their goals that they forget which rules mustn’t be broken. If, however, you understand the rules that absolutely, positively, 100 per cent of the time must be adhered to, you can then proceed to break the rest with impunity.

So think about your current job. How much of your time do you spend having to follow rules and regulations, policies and procedures? Now ask yourself, ‘Am I happy doing that for the rest of my life?

Over to you

Here are some questions to stimulate your thinking. What kind of work might be better suited to your adaptable, opportunistic nature?

- Without quitting your job, how could you pursue more projects that play to your strengths? Consider projects that allow you to focus on strategy and the big picture rather than the detail of implementation. Or work that encourages you to change your approach to meet the needs of different colleagues or customers rather than delivering the same script every time. Go to your boss, explain the kind of work you’d most enjoy (and perform best at) and see if you can change the direction of your career.

- Which of your friends or colleagues do you envy for the amount of freedom that they have in their work? Go talk to them. See what you can learn. And if you love what you hear, explore how you could switch careers.

- What hobbies or pursuits might allow you to express your irrepressible nature outside of work? If you have to be rigorous and careful at work, at least look for something outside of work that allows you to be yourself.

Get organised

Being spontaneous has its upside – you respond quickly to opportunities, while others are still mulling over what is the best course of action. But your aversion to detailed planning and reluctance to be tied down mean that other people may see you as disorganised.

So you need to fight your inner rebel. Get more organised, even though it’s not your ideal way of working. Otherwise no boss is going to recommend you for a promotion if it looks like you’re struggling to stay on top of the work you have now. No client will let you make the same mistake twice. Even loved ones may feel let down when you forget birthdays or important events. Sure, you may feel that you’re coping just fine. But everyone else who is higher on Conscientiousness than you – and that’s most people – will notice when you forget appointments, make mistakes and lose track of anything from a piece of paperwork to entire projects.

Look at it another way. Say you go to a restaurant with a large group of friends. When a waiter takes your table’s order and doesn’t write anything down, doesn’t that make you nervous? You feel so much better when the waiter writes it all down. Even better when he repeats it back to you, emphasising that the sirloin should be medium-rare and the T-bone well done, plus no dressing on the side salad.

Or imagine if an architect came to your home to discuss putting in a spanking new kitchen, knocking down walls and changing the entire layout of your living space. He measures up the rooms and says that he’ll commit them to memory. Hold on. Memory? Wouldn’t you feel a little more secure if he wrote it all down? And preferably not on a ragged scrap of paper, but in a notebook or some kind of folder.

Become your best: Relying on systems and people

When it comes to making a great impact on the people you know, it’s not so much how organised you are as how organised they perceive you to be. History probably tells them that you’re not that disciplined.

Time to turn over a new leaf. Get a system that works for you. Scribbling notes on separate pieces of paper or Post-it notes is not very effective. Use a diary, an electronic organiser, a wall chart, whatever works for you. Writing things down in front of your colleagues, your boss, your loved ones can have a rather mesmerising effect on them. The simple act of writing it down helps them to believe that it might actually get done.

Look among your friends and colleagues for people who are completely on top of their work. Ask them how they do it. Learn from them. Adopt their system or adapt it to make it work for you.

I realise that this may be painful advice for you. You hate to feel shackled by lists and plans and all this attention to detail sounds like such a drag. But I’m not suggesting that you have to be anywhere near as meticulous or, frankly, uptight as some of your High-Conscientiousness counterparts – just a little more organised than you would naturally like to be. This is ultimately about winning other people’s trust that you won’t let them down.

If you’re lucky, you may be in a position to hire someone to pick up the pieces after you. Perhaps an accountant to keep track of your finances. A personal assistant to book in appointments and make sure that you turn up on time. Or a deputy manager or chief of staff whose sole purpose is to make sure nothing falls through the cracks.

If you have the money to do it, I strongly suggest surrounding yourself with the best people money can buy. And by ‘best’, I mean people who are diligent, careful and good when it comes to attention to detail. Certainly, this is a must if you work for yourself. I work with so many entrepreneurs and senior managers who tell me that their personal assistants or seconds-in-command are worth their weight in gold.

I coach Rebecca Harper, who runs recruitment agency Grade A. She’s fun to be around, but – like many Low-Conscientiousness people – boy did she used to be forgetful. I surveyed her clients and they’d been frustrated by her absent-mindedness more than a few times. Her solution? She bought a beautiful, leather-bound notebook. Now when she says that she’s going to send me a book or set up a meeting to introduce me to someone, she writes it in her ever-present notebook, and I know it’s going to happen. So people can change. Keep up the good work, Rebecca!

Impose structure on others and they will thank you for it

Say you invite a friend to join you for dinner one evening. You explain that you’ll cook the main course if she will make a dessert. When she asks, ‘What time should I come round and what should I make?’ you reply, ‘I’ll be in all evening so come whenever suits you and bring whatever you like.’

That may seem perfectly accommodating on your part, but you must learn that for many people, too much freedom of choice isn’t a good thing. They see it as uncertainty, a lack of clarity, something to fret over. If your friend is of the High-Conscientiousness persuasion, she may worry over exactly what time to arrive. Would 7 o’clock be too early? What if you’re still doing something else and she interrupts you? Would 8 o’clock mean that you would end up eating too late though? And what should she bring for dessert? Without knowing what you intend to cook, she may worry that her contribution will clash with your meal rather than complement it.

As a Low-Conscientiousness person, you probably think this scenario is ridiculous. How could someone get worked up over something so trivial? What you must, must realise is that other people are wired in differently. Seriously, you must. Because where you see freedom to choose how to behave, others may see a lack of clarity. When you feel a sense of autonomy, others may feel uncertainty over what they’re supposed to do or how they’re supposed to do it. They can feel like they’ve been dumped into the middle of a situation, that they’re being given insufficient guidance, support or leadership to perform at their best. And in the ensuing confusion, you could easily end up with disappointment.

Of course, a little mix-up between friends over dinner is hardly disastrous. But you may come to more grief if you’re giving instructions to a decorator over which areas of your house you want repainting and which ones absolutely must not be touched. Or if you’re telling a colleague or a supplier what you expect out of the major new project you’re embarking on together.

So consider how you give instructions. You may enjoy having a wide remit, but others may see it as being cast adrift. Be prepared to give more guidance to others than you need for yourself. You need to let people know what you expect of them.

Become your best: Giving clear instructions

Always bear in mind that while you see too much direction as stifling and unnecessary, other people may appreciate that guidance and clarity. When briefing people, use the following questions as a checklist and make sure that you can tick off everything that others may wish to know:

- What do you expect of a successful conclusion? What are the final results, the products, the outcomes that you want? If you give vague instructions, such as, ‘Please produce a great brochure to launch the new product’, would you be as happy with a two-page leaflet instead of a full-blown catalogue or one in black and white versus full colour? Often, giving clear instructions is as much about saying what’s off limits as what you want to see.

- How do you expect it to be done? What is the approach, the process, the method you recommend? What are the tools or resources you suggest for the task? How much money is available? You may not wish to be too prescriptive, but remember that others will probably appreciate a little advice on how to tackle the task. Explain that you are giving suggestions as to how it could be done, but you would welcome an alternative approach too. That way you give guidance, but also provide the option to do it differently (and hopefully better).

- When do you expect it to be done? What’s the deadline for the overall task or project? Again, be careful of fuzzy language. Does ‘by the end of the year’ mean by 31 December or the end of the financial year, in the spring? Consider if it would make sense to have mini-deadlines along the way to measure progress and check that the work is on track. If the overall deadline isn’t for several months, you would be wise to check how people are getting on perhaps monthly or every few weeks, for example. Better to catch problems and crossed wires early on than discover at the very end that things have gone horribly, terribly wrong.

- Why is this task important? People often perform much better when they have at least some appreciation of the context for the task. If you can explain how people’s work fits into the bigger picture, you help your High-Conscientiousness counterparts to avoid getting too bogged down in detail. Consider also which aspects or components of the task are most important. If you ask someone to do A, B and C, are they equally important? Or are any parts of the task more critical than others?

Slow down to contemplate, deliberate, plan

I worked one on one with Michael, a Low-Conscientiousness company director, who told me:

I deal with all of my emails as they come in. I read an email and respond to it straight away, but occasionally I realise the moment I’ve hit the send button that the email was too blunt or half complete and that I should have mentioned another couple of points.

I shared with Michael a tip I’d read somewhere: that you can save emails as drafts rather than send them right away. Now he replies to emails as they come in, but only hits the send button three or four times a day, say at 10 a.m., lunchtime, 2 p.m. and 5 p.m. That gives him a couple of hours after composing an email to go back and change something if he needs to, which he does frequently.

But what was more interesting was how Michael made decisions in all quarters of his life. He once took a job and quit three weeks later. He had proposed to his first wife within two months of meeting her. And he had – a long time ago – stolen a bar stool from a pub as a dare at university. He admitted that he often saw decisions as challenges taunting and goading him into action.

You probably make lightning decisions in at least some areas of your life. Perhaps you’re considering something as relatively mundane as how to respond to an email or what bottle of wine to pick up at the supermarket. Maybe it’s a bit more important, such as deciding whether to quit a relationship or start a new job. In any case, you don’t see the point of pondering it for too long – you hanker for action.

But moving too quickly could occasionally be rash or downright crazy.

High achievers – such as leading entrepreneurs and philanthropists – often make it seem as if they have charged ahead, that they are the first to launch the world’s first this or that. But what we see is often the stage-managed press launch of initiatives that may have been months or even years in the making. Successful people are never reckless. They weigh up pros and cons and decide on the level of risk they’re willing to take.

I recently met Patrick White, serial entrepreneur and former chief executive of several large international businesses. His last business had 600 staff and made US$2 billion a year. Now a multimillionaire with properties around the world, he shared with me the secret of his success. He called it his ‘six Ps’: ‘Prior planning prevents piss-poor performance’. Sage words.

Become your best: Making truly great decisions

Real emergencies are rare. Few decisions have to be made in a matter of moments. So before you throw your energies behind any project, ask yourself these questions:

- Why are you pursuing this right now?

- What are the pros and cons of waiting 24 hours, a week, a month?

- How long would it take to become better prepared? Is that too long?

- Who should you ideally have onside to make this a success? And who (if anyone) do you already have onside?

- Do you have the expertise, resources, experience and credibility to make this work?

Just 10 to 15 minutes. That’s all I’m suggesting. Take a quarter of an hour to work through these five questions and you will help yourself to gauge whether your idea is sure to be a winner.

I’m not recommending that you take the painstaking and sluggish approach to decision making that certain High-Conscientiousness people may advocate. Slowing down, though, even a little – at least with the bigger decisions in life – can pay huge dividends.

Anna Gillespie, a newly recruited marketing director, admitted that her eagerness led her to make many snap decisions.

I took on a great team with lots of ideas and I love to respond to them. If it’s new, I always see the upside and want to give it a go. Six months into the job, the managing director took me aside and said that our marketing didn’t have a focus. In trying to do everything, I was achieving nothing. Plus, what I didn’t realise was that every time I switched direction, I was confusing and exhausting my team. The moment they got good at something, I’d change the rules of the game.

Her solution?

Whenever I hear a new suggestion, I say, ‘Let me think about it.’ It is so simple, but forcing myself to take 24 hours to ponder an idea is usually enough to make a more reasoned decision.

Slow down. Fight your gut instinct. Ask yourself a handful of questions and you ensure you make decisions that are considered risks rather than reckless ones.

Make the most of yourself – for High-Conscientiousness people

You’re the go-to guy or gal for getting things done. If a friend needs someone to organise a surprise birthday party, you’re the one who can be relied upon to find a venue, book a caterer, send out the invitations and make sure everything is perfect when the guest of honour walks through the door. If your boss needs someone to oversee a complex project, you can work out who should be doing what and by when, and how much it will cost.

The tendency to think ahead makes High-Conscientiousness people a real asset to most organisations as well as to themselves. Health researchers Margaret Kern and Howard Friedman even noticed that High-Conscientiousness people tend to live between two to four years longer than low scorers, possibly because they are more careful about their health as well as everything else.

As a High-Conscientiousness person, you do what’s right, playing by the rules and delivering results. But your attention to detail, high standards and enthusiasm for plans can be as much of a weakness as a strength.

Go with the floe

No, that’s not a typo. Dr John Nicholson, a leading psychologist in the 80s and 90s and an ex-boss of mine, likened life to skating on ice floes – the sheets of floating ice that sometimes detach themselves from the vast ice fields blanketing the Earth’s poles. If you’re on one of those drifting slabs of ice, you can never predict where the currents will push you.

And that’s a pretty good metaphor for life. No matter how hard you may try to control your circumstances, you will always be affected by unpredictable currents. In fact, change is the only constant. Technology moves at dizzying speeds. Fashions and tastes move on. Governments come and go. Countries go to war and new countries are born. Businesses grow and shrink, perhaps adding new people to the team, firing them or changing everyone’s roles. Friends move away and new friends come into our lives. All around us, people are born, people die and everyone in between gets older.

So my point is this: no plan can take into account everything that could possibly happen. No venture in life can be 100 per cent certain. Life is inherently messy, unpredictable and fraught with ambiguity. Whether you’re trying to find The One, your perfect partner in life, or launching a multi-million pound project, you have to accept that there will always be an element of chance involved. The key to life isn’t about holding back, it’s about taking action despite what could go wrong.

Do it anyway

A smart buddy of mine often says, ‘In the short term, we regret the things we did, but, over time, we regret the things we didn’t do.’ And he’s right.

High-Conscientiousness people are sometimes slow to act. Perhaps you’re like this too – wanting to be certain that your decisions will turn out right.

Sure, you could stay in the same job because you know it feels safe. You could decide that’s better than trying your hand at something more exciting – perhaps a new job or setting up your own business. But then you could decide never to holiday abroad to avoid all those diseases, the humidity, the strange food, the risk of terrorism.

Isn’t it better to give something a go and say that you tried than get to the end of your life and say that you played it safe? Do you want to be a quitter because you quit before you even started?

No, of course not.

Over to you

As a High-Conscientiousness person, you’re probably more cautious in your decision making than many other people. But do you always need to be quite so careful in your approach?

Reflect for a moment and consider a decision that you regret not having made.

- What was the situation?

- What did you fear would happen?

- What actually happened?

- What would you do differently?

We all have to make decisions about the future. Sadly, we don’t have the benefit of a crystal ball to guarantee our success. We must all accept that there’s an element of risk with most decisions.

High achievers are willing – at least occasionally – to make bold moves, to take intelligent gambles. That’s not to say they’re happy taking brazen or ludicrous risks. Instead, they accept that no venture can be entirely without risk. They weigh up the pros and cons and plan for the worst eventuality, but hope for the best. And you can too.

Become your best: Making decisions that lead to action

Should you take that new job or promotion? Should you embark on a new project or decide to start a family? Questions, questions, questions.

You will never have enough information to make the perfect decision. Life is about making decisions based on the information you do have. Bear in mind that deciding not to move forwards is making a decision to stick with the status quo, to put up with the circumstances you’re currently in.

Here’s a step-by-step technique for making those big decisions and moving forward regardless:

- Define the situation, problem or opportunity. Write a few lines about it. Seeing your thoughts on paper can help you to consider them more rationally than if you simply allow the thoughts to bounce around your head.

- List your options. Try to come up with at least four different options. Avoid getting into black-and-white thinking that allows for either one choice or another. Look for shades of grey that permit you to act but without risking everything at once. If you’re thinking of quitting your job for a new one, perhaps you can negotiate to spend a few days shadowing your prospective boss or meeting members of the team one on one rather than accepting it straight away. If you’re thinking of leaving your partner, consider a trial separation as an option or moving in with a friend for a week first. Seeking at least four different options may point up alternatives, allowing you to move forwards without committing everything at once.

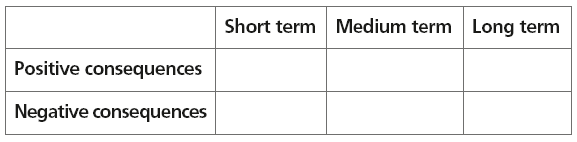

- Complete a table for each option. In terms of consequences, think not only about yourself but also those who are close to you – perhaps your family or a business partner. Include in your assessment factors such as how your values, finances, health and happiness may be affected. Use your judgement to decide what counts as short- versus medium- and long-term consequences. The long-term consequences of, for example, taking out a huge loan to start up a business may be more far-reaching than the consequences of taking an assignment in another part of the country for the company you currently work for. Don’t worry too much about the timeframes – focus simply on listing the pros and cons for your different options.

- Identify the rational best option. If you were advising a friend on this issue, which option would you recommend that he or she take? That’s not necessarily the right option for you though. You still have one concluding step to take.

- How do you feel about each option? Gut instinct is much maligned by rational decision makers, but facts don’t always give us the right answers. In fact, the first four steps of this process are not designed to give you the answer; they are designed to tap into your feelings and intuition. If you have a sense of trepidation about one option, but feel a hit of excitement when you consider another, that may be all you need to make a decision that’s right for you.

Yes, there can be a time and place for gathering data and research. But all successful people eventually have to rely on their instincts. Ted Turner, founder of 24-hour news channel CNN, wrote in his autobiography:

Henry Ford didn’t need focus groups to tell him that people would prefer inexpensive, dependable automobiles over horses, and I doubt that Alexander Graham Bell stopped to worry about whether people would prefer speaking to each other on the phone.

So when he started his news channel, he didn’t conduct any formal research about it either. He thought about it, weighed up the likely consequences, then did it.

Your feelings are part of what makes you human. Psychologist and author Marsha Linehan says that people who make decisions based purely on facts and logic are trapped in a state of ‘reasonable mind’. On the other hand, people who make decisions based too heavily on their emotions are caught up in ‘emotion mind’. Only people who integrate thoughts and instincts, facts with feelings, can experience the balance of ‘wise mind’.

Learn to trust your judgement. Don’t be too calculating in all you do. You may be surprised how good your decisions can be.

Break the rules – at least occasionally

High-Conscientiousness individuals are usually loyal friends, stalwart team players and great organisational citizens because they find it easy to play within the rules of the game. If an organisation says that all decisions can only be made by managers at Grade 7 and above, you probably know better than to break the rules. If your spouse says that you should put the kids to bed at 9 o’clock, you will make every effort to do so.

But high achievers rarely play entirely by the rules.

Because rules can outlive their usefulness, over time they can get in the way of progress. Take the rule that you should put the kids to bed at 9 o’clock. Sure, that’s fine when you have an eight-year-old. But at some point, as they reach 10 or 11, 12 or 13 or older, you have to let your kids stay up a little later. You can’t keep sending them off to bed at 9 o’clock when they’re 22!

Same goes for the workplace. Say there’s a rule stopping you and other employees at your grade from making decisions involving more than £10,000. Anything over that and you have to submit a formal proposal and await sign-off from your boss. It makes sense initially, when you’re new to the job. But then you get better at the job. You gain experience. You know the job inside out – certainly better than the fresh-faced manager who’s just been parachuted in as your new boss.

Imagine now that your new boss isn’t coping with the workload. The proposals are piling up in his in-tray, customers are fuming and nothing is getting done. You could wait for him to drown under paperwork and customers to walk away because the rule says that you have to leave the big decisions to him. But you know the job, so you could place the orders yourself. Technically, that’s breaking the rules; but it would get the work done, keep customers happy and get your new boss out of a jam.

Many organisations have bureaucratic rules that seem to stop people from succeeding rather than helping them. Many rules are merely habits or routines that people have done for ages and got used to.

‘That’s the way it is.’

‘That’s just how we do it.’

But rather than adhering rigidly to the rulebook, ask yourself, ‘Why? What’s the intention behind the rule? Is it still fit for purpose?’

‘It always helps to have someone who can say, “No, we can do it faster this way” or “We have to break the rules, even our own rules, to get things done”,’ argues Tom Anderson, mega-multi-millionaire co-founder of social networking site MySpace. Tradition said that people maintained friendships in person or over the phone. But websites such as MySpace and Facebook challenged those old conventions, creating a multi-billion dollar sector in the process.

Rules need to be constantly reviewed to establish if they are still appropriate. You may need to challenge conventional thinking, make people uncomfortable and push the boundaries of what’s accepted. Are you ready to be – at least occasionally – the non-conformist, the rule-breaker, the one to shake things up?

Become your best: Challenging your own set of conventions

Rules and regulations can act as useful guidelines for our behaviour. You wouldn’t want an airline pilot to deviate from established safety protocols when landing the plane you’re on, would you? And what about a heart surgeon trying out a crazy new idea she overheard when your loved one is on the operating table? That said, yesterday’s rules can quickly turn into shackles if we obey them mindlessly. The world moves on and what may have worked in the past could stop us from being effective or more creative in the future.

This exercise is aimed at periodically shaking up the rules, assumptions and values that you follow. Simply complete the following sentences:

- People would be upset if I …

- It would be wrong to …

Two simple sentences, but so many ways you could complete them. And that’s the test here. Aim to use the two sentences to come up with at least 100 complete sentences. That may sound like quite a lot, but the first couple of dozen sentences you come up with won’t really challenge your assumptions. You only discover your unspoken assumptions when you push yourself to the limits. I suggest that you do this exercise perhaps once or twice a year.

You can do this either on your own, to scrutinise your own life, or with a team at work, to examine the rules that bind your organisation. The idea is to consider all of the rules, conventions, assumptions and established ways of doing things. Once you’ve listed them, consider why people would be upset or why it would be wrong. Would everyone be upset? Would it be wrong in every situation? Do or would any of your friends, customers or rivals do it differently?

Let’s see how this challenging might work in practice.

In your personal life, you might say, ‘People would be upset if I quit my job.’ But who would be upset? Which is more important to you – your own job satisfaction and mental health or the expectations that your friends and relatives may have of you?

More controversially, you might think, ‘It would be wrong for my teenage daughter to have sex until she is married.’ But consider the pros and cons of your rule. Sure, you might be able to persuade her not to have sex. Alternatively, she could end up having sex anyway, but feel unable to tell you about it because you made the topic taboo. Would a more flexible rule be more appropriate?

At work, say a colleague comes up with the sentence: ‘It would be wrong to give away our product for free.’ Well, would it? Other businesses do that. They allow customers to use a product online and benefit from advertising to make a few pennies every time a customer accesses the web page. They offer freebies, knowing that customers often feel obligated to make some other purchase. Alternatively, a business could offer the product for free for the first three months, hoping in that time to persuade customers the product is so good they can’t live without it.

Accepting the established rules is allowing yourself to stagnate. Challenge the rules you hold dear – at least once in a while.

Let go of the small stuff

You have high standards. And let’s be honest, you probably produce work that is of higher quality than many of the people around you. You work harder, you pay more attention, you care more – which is great when you have the time to work at your own pace.

But what happens when you’re under time pressure, when you have more work than hours in the day? If you have multiple tasks but know that you can only carry out a handful of them. How do you cope?

Suppose you have to get a proposal to a prospective client. The deadline is 5 o’clock on Friday afternoon. The client has repeatedly stated that late submissions won’t be considered – they won’t even be read. Your boss has only just asked you to work on it, so you have less than three hours to write an entire proposal that has always taken you at least six hours to complete. What would you do?

I coach quite a few High-Conscientiousness people who struggle with their workloads. They care so much about their work and hate to see a document go out with even a single typo or misaligned paragraph. But when there’s too much to do, you need to prioritise. Sometimes it’s better to produce something that is ‘good enough’ rather than let down a client, teacher, friend or colleague.

I worked with Anoushka, a High-Conscientiousness executive who took a new job to build a new division within an engineering firm. Three weeks in and she was hating it. She hadn’t had the time to pull together a plan because she spent all of her time in meetings. She had 20 to 30 meetings every week, often overlapping, taking up 30 to 40 hours of her week. Colleagues were all so keen to make her feel included and she was afraid to say no because she didn’t want to appear standoffish.

I helped her to see that most of the meetings weren’t helping her to achieve her goals. Within the year, she would be judged on the quality of the team she brought on board and the money they made, not on the number of meetings she attended. So we worked together on prioritising. On pruning her schedule, saying no to a few meetings and freeing time up to work on the plan for her new division.

For other meetings, she decided that she would simply walk out, explaining to colleagues that she could only stay for part of the meeting and then leave when she’d got the gist. Yes, some people initially thought it was a little rude, but she created space in her diary to formulate her business plan, recruit a team, and seek out and win new customers. Ultimately, the money she brought in for the firm proved that she had taken the right approach.

Learn to prioritise. Scrutinise your schedule and ruthlessly focus on what you absolutely must do. Only then can you be truly effective.

Become your best: Applying the 80/20 rule

What do property, pea harvests and an Italian economist have to do with your effectiveness?

Quite a lot actually. In the nineteenth century, Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto identified that 80 per cent of property in Italy was owned by only 20 per cent of its people. He also spotted that 80 per cent of the pea harvest in his garden came from 20 per cent of his peapods. From this we get the famous Pareto principle, the 80/20 rule, which states that 80 per cent of the output you get comes from only 20 per cent of your inputs.

It’s probably true of how you spend your time too. Of the tasks you need to do during your day, only a proportion of them really matter. Let’s not argue whether it’s a little more or less than 20 per cent of your tasks. The point is that a small proportion are more important than others.

Say you’re packing your suitcase to go on holiday or a business trip at short notice. Sure, you would like to take pressed shirts with you and think carefully about what to pack for when you get there. But some tasks are more important than others – like making sure that you’ve got your tickets and passport and whatever work you may need for your trip. Those are the 20 per cent that count.

Say you need to write a report for your client. You would be better off spending your time putting together some bullet points with the key information you need to convey than making sure it’s all formatted beautifully. Better to get the bare bones of your pitch across than not to hand it in at all.

We’re all inundated by demands on our time but, when we have too much to do, we should separate what is important from what is merely urgent. We need to focus on what we must do – what will deliver the greatest benefit – as opposed to what may be clamouring most loudly for our attention.

Do you already make lists of tasks you need to achieve each day? If you don’t, then making one is a good start. Draw up a list at the end of every day of all the tasks that you need to do the next day. Then note down the most critical ones. Of course, many of your tasks are important, but some are genuinely critical. Those are the ones that will make the biggest difference to your day, your career, your life. So which are they? Which are the ones that you should underline, put a star against, mark up with a highlighter – at least in your head if not actually on paper?

Prioritise how you will spend your time the next day. Get used to taking that perspective on all of your work and tasks in life too. Keep reprioritising throughout the day. When you are handed a new task to do, consider whether it is a ‘must do’ or merely a ‘should do, if I have time’. If you believe that a new task is critical and must be done, then one other ‘must do’ task has to fall off the list.

Don’t step into the trap of trying to squeeze more and more work into your day. The whole point of prioritising is to ensure that you complete the few tasks that add the most value, the roughly 20 per cent that make 80 per cent of the difference.

Play to your strengths

The advice in this section shows you how you need to adjust to shifting priorities and be more adaptable some of the time. However, I’m not suggesting you should aim to become the kind of disruptive risk-taker that Low-Conscientiousness individuals can be.

In fact, you will thrive and feel most fulfilled when you can play to your strong points, when you can make plans, organise your world, and be careful and considered with your decisions. So bear that in mind as you pursue future opportunities. If you’re looking for a new job, look to join a team or pick a role that respects planning and forethought. Perhaps you may be best off in a large organisation with established traditions and conventions. Avoid situations that require seat-of-the-pants decision making in chaotic and ever-changing environments.

In your personal life, recognise that you will always be frustrated by Low-Conscientiousness people who hate being tied down by plans. But also realise that you will never change them. You can either put up with them or move away from having them in your life.

Respect your preferences and strengths. Then you can be both successful and fulfilled.

ONWARDS AND UPWARDS

Remember that Conscientiousness – like each of the other personality dimensions – is a continuum. Even two people who are both Low-Conscientiousness may behave in different ways from each other if one is actually much lower than the other. Same goes for two High-Conscientiousness individuals.

Neither end of the range is innately better than the other. When I work with teams, I notice that bosses often recruit people who are all like themselves – leading to entire teams consisting of rule-breaking mavericks who throw themselves into massively risky situations or overly careful planners who analyse everything to the nth degree. The lesson? You need a bit of both. If you’re a Low-Conscientiousness individual, get more organised and structured for the sake of yourself and those around you. If you’re a High-Conscientiousness person, learn to let go a little more, to take the occasional gamble.

Here’s a rough and ready reminder of the key differences between the two ends of the spectrum:

| Low-Conscientiousness | High-Conscientiousness |

| Enjoy challenging the status quo. | Behave as good organisational citizens. |

| Typically adaptable, spontaneous, unorthodox. | Tend to be organised, careful, prudent. |

| Jump in. | Hold back. |

| May take on too many risks. | May be too risk-averse. |

| Break rules and push boundaries. | Adhere to rules and live within boundaries. |

| May be seen as disorganised, unreliable. | May be seen as uptight, inflexible. |

If you scored lower for Conscientiousness:

- Look for unstructured, entrepreneurial environments and steer clear of environments that require lots of rules and bureaucracy. That way you can be yourself and play to your strengths.

- Get at least a little bit more organised and take slightly more time over your decisions. Otherwise, people may see you as disorganised and unreliable – and those kinds of perceptions may make them reluctant to trust you with more responsibility or promotions.

- When giving instructions or delegating work, be sure to give others more guidance than you need for yourself. Remember that, while you may not enjoy being told what to do, others will probably appreciate the extra support.

If you have a somewhat higher score for Conscientiousness:

- Bear in mind that most situations in life require us to make decisions without having all of the information we need. No decision can ever be guaranteed. All you can do is plan for any eventuality and then do it anyway.

- Occasionally question the rules and assumptions that you feel obliged to follow. Consider at least once a year which of the rules – in both your personal and professional life – may need review.

- Recognise that your high standards can be both a strength and a weakness. When you have too much work, remember that ‘good enough’ is sometimes more appropriate than perfect. Use the Pareto principle, the 80/20 rule, to prioritise and focus on what’s most important.