06

“The great gift of human beings is that we have the power of empathy.”

Meryl Streep, actress

It’s Saturday night and you’ve arranged to go out for dinner with a friend. Your friend asks, ‘Where would you like to go for dinner?’ Are you the kind of person who answers the question with a question, replying, ‘I don’t mind – what would you like for dinner?’ Or do you speak your mind, perhaps saying that you’d quite like to try the new French restaurant or have a serious craving for Thai food?

Sensitivity is the personality dimension that describes the extent to which you put the needs of other people above those of yourself. People who score highly on Sensitivity are incredibly attuned, sensitive to others’ feelings. They put other people’s needs ahead of their own. By replying that you don’t mind where you go for dinner, you may end up eating at an Indian restaurant, even though Indian may secretly be your least favourite kind of food.

Lydia, a friend of mine, is so high on the Sensitivity scale that she always puts everyone else first. Whether someone’s talking to her about what film to go and see, where to go for dinner, what projects to give her at work, how she’d like to decorate her home, she rarely expresses an opinion because she’s so content to be a good friend, a good colleague, a good wife.

People who are low on Sensitivity are much more direct and to the point. They say what they think. Take Simon Cowell, for example. The famously forthright judge on shows such as Britain’s Got Talent and The X Factor earns $40 million a year for appearing on American Idol alone. And what does he do? He speaks his mind. He tells performing artists what he thinks. Most people are too afraid to say to someone’s face, ‘You’re rubbish’, but not Simon. He simply says what the viewers at home are probably thinking anyway. I can’t imagine that Simon would ask what you would want for dinner in our scenario above. He’d simply tell you what he wanted to do.

Lydia and Simon inhabit the two far ends of the Sensitivity spectrum. How do you stack up?

Your Sensitivity

Flick back to Questionnaire 5 on page 12. Award yourself two points each time you agreed with any of the following statements: 2, 4, 6 and 8. Award yourself two points every time you disagreed with any of the statements numbered 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and 10. You should have a score between 0 and 20.

A score of 10 or less suggests you’re low on Sensitivity. A score of 16 or more suggests that you’re high on Sensitivity. A score between 12 and 14 suggests that you have fairly average levels of Sensitivity.

Find the sections in the rest of this chapter that relate to your personality profile. If you’re average for Sensitivity, you may need to read both descriptions and pick the advice that seems best suited to you.

What kind of person are you?

As with each personality dimension, your level of Sensitivity affords you a unique set of talents. Low-Sensitivity people are good at making tough decisions, while High-Sensitivity people are more tender-minded, caring individuals who naturally seek to please others. Whether you’re tough or tender – or somewhere in between – read on to discover more about yourself.

The Low-Sensitivity person: straight-talking, frank and outspoken

You’re the kind of person who likes to speak your mind and get to the point. If people ask you for your opinion, you tell them what you think. If they ask you questions, you give your answer. Life’s too short to waste time going round in circles. You prefer to say what you think. If you know that something is right or true, you’d much rather get it out into the open.

You are probably frustrated by people who won’t tell you what they think, who shy away from sharing their opinions. When you ask a direct question, you’d appreciate an honest answer. But instead they skirt around the issue, bewildering the situation. Why won’t they say what they want?

You’re not frightened of making tough decisions, of taking a stance and standing up for it. You know that not everyone can be kept happy all of the time – that’s just unrealistic. Sometimes you need to confront people. If they’re doing something wrong, perhaps letting you or other people down, maybe making unreasonable demands, then why shouldn’t you speak up? Someone needs to. If friends are making foolish decisions about their love lives, colleagues aren’t pulling their weight or your children aren’t eating their greens, they should be told. You feel compelled to speak the truth, to present the facts and set the situation right – even if that means a bit of disappointment, a few ruffled feathers or unpleasantness in the short term.

You hate to let others walk all over you, which can occasionally lead to a disagreement, a few heated words or an outright argument. But you sometimes relish the challenge of a good debate. And you’d rather be respected for having a view than be popular for saying nothing.

The High-Sensitivity person: diplomatic and tactful to the end

You’re the sort of person who always knows how other people feel. But it goes deeper than that. When other people are feeling excited or depressed, angry or bored, you not only understand how they feel, but you feel that way too. Whether they’re happy about getting a job offer or furious over an argument, you feel a little up or down with them as well.

You empathise with people so readily that putting yourself in others’ shoes isn’t just something you can do, it happens automatically. You can’t help but know and appreciate how they feel.

Having such an exquisite attunement to other people’s feelings means you’re quick to spot what you have in common with people, rather than what separates you. You find it easier to agree than disagree. And when you have an opinion, you try to be diplomatic and tactful. You choose your words, your tone of voice, manner and timing with care. You don’t want to offend anyone or put anyone out if you can help it. In fact, your whole nature is to be cooperative rather than combative.

When you come across people with difficult points of view, you instinctively tiptoe through the minefield of their emotions. And you’re happy to be flexible. Because of the relationships you have with them, you’re willing to give way, make concessions or even back down entirely. You do whatever it takes in the interests of preserving harmony.

You realise that putting everyone else first means that you sometimes come last. That you sometimes agree to more than you would have liked. That you may get saddled with the unsexy work assignment or a decision that wouldn’t have been your first choice. But for the most part, you don’t mind these things.

Make the most of yourself – for Low-Sensitivity people

What kind of a person do you think makes a good bailiff? Remember that bailiffs repossess furniture and goods from people who have maxed out their credit cards and can’t pay their debts. So who would you hire for the job?

I watched a firm of bailiffs interview one particular candidate. Andrew stood at 6 foot 4 inches, he was built like a rugby player, spoke in a monosyllabic growl and was currently working as a nightclub bouncer. Oh, and he practised kickboxing in his spare time. The perfect candidate, right?

Wrong.

The firm of bailiffs turned him down. The boss explained to me that its best collection officer was in fact Brenda, a softly spoken 5 foot 2 inches woman in her late forties. That’s because bailiffs aren’t allowed to get physical. Contrary to the popular misconception that bailiffs are bruisers, they can’t break down doors or push people around. Instead, Brenda charmed homeowners into opening the door so she could take away their 42-inch flatscreen TV, Xbox and sofa. She told people that she understood their situations and felt their pain. She persuaded potentially volatile people to let down their guard and let her in.

Taking the direct route doesn’t always get results. Stating your requests and speaking your mind means that people always know where you stand. Trouble is, most people can simply say no.

Ask a debtor to hand over her DVD player and she can tell you to go to hell. Point out to a smoker that his cigarettes will kill him. Tell a colleague that the way he’s doing something at work isn’t the most efficient way. Or try explaining to your customers that they’re making a mistake by not choosing your product. What do you think they will say? Will any of them thank you for your advice? Will any of them actually change their behaviour?

Probably not.

As a Low-Sensitivity person, you’re the voice of reason, logic and rationality. The hitch is that most people are deeply illogical, emotional, unfathomable. You may be ‘right’ much of the time, but that doesn’t mean people will listen. If you want to be more successful, to achieve more in your relationships with other people, you may need to take the indirect route at times. The suggestions given in this section show you how.

Understand the psychology of influence and persuasion

Telling the facts and explaining what you want doesn’t always work. So what does?

Working with business leaders to help them become more successful, I get to observe a lot of managers in action. In one organisation – an investment business catering to wealthy individuals – the chairman is a self-made man who has grown the firm over two decades of hard work. But I spotted that ideas from his team often failed to impress him – even when they clearly had merit for the business.

The employees who succeeded in winning his support for projects and reaping the career rewards realised that business benefit was of only secondary importance. In order to succeed, they had to fan the flames of the chairman’s ego. When I confronted him with my observation, he denied it at first. But as an outsider, I could see that an idea’s benefit to the business without enough fan-waving was always doomed.

Like the chairman, most people have a hot button – a source of inner motivation that drives them and to which they respond. For some people it’s money, pure and simple. For others it’s popularity or status and the need to impress colleagues, friends or family. Others may seek security, to feel good in the eyes of God or to feel included as part of a team or family. It could be the need for recognition – to be appreciated as a great leader, a loving parent, an expert on a topic. Or maybe to have an easy, low-stress life.

Not everyone has the same motivation. And, to complicate matters, people sometimes have different motivations in different situations. You can bet, however, that few people are motivated purely by doing what is ‘right’ or ‘best’ in a situation.

High-Sensitivity individuals naturally get into the heads of other people to understand their motivations – what they yearn for, their hot buttons. But you can learn to do this too. Do it and you unlock the secrets to influencing and persuading the people around you.

Become your best: Uncovering people’s hot buttons

People rarely talk about what motivates them unless they know you well enough to open up. Even then, many people aren’t aware of their own true motivations – they may say one thing but mean another.

Your assignment is to figure out what motivates different people, what makes them tick. Imagine that you’re a private detective who has been paid to work out the motivations of the key people in your life. Your ultimate goal is to put your findings into words and write a report. I suggest that you write at least a handful of bullet points for each person. Believing that you understand someone’s motivations is very different from being confident enough to commit them to paper – even if it’s for your eyes only.

Begin by making a list of half a dozen people who are important in your life and career – perhaps colleagues, your boss, family members. Then observe them and try to work out their hopes, fears, likes and dislikes. In particular, see if you can answer the following questions:

- When these people are presented with new ideas or proposals, what makes them agree to something? And what makes them say ‘No’?

- What is each person passionate about?

- How would you describe each person’s personality? Think of them on each of the seven personality dimensions within this book. Would you say that they were high, average or low scorers for each dimension? Write a short profile on your people and how they come across.

- What should you say or do to get them to say ‘Yes’? How can you prepare and pave the way to increase your chances? What buttons do you need to push?

Over the days and weeks, collect evidence to back up your answers. What is it that each person does or says? How do their tones of voice alter when they’re happy or displeased? How do their facial expressions betray their feelings?

Remember that the brain contains a series of pathways. This kind of mind-reading may not come so naturally to you, but the more you do it, the better you can get. So start now.

Learn to pull as well as push

A friend of mine, Craig, won’t go to the dentist. He hasn’t been to one for at least ten years. All of his friends – including myself – have argued that he should. We’ve warned him about the perils of tooth decay and gum disease. But will he listen to reason? Hell, no. The more we’ve tried to tell him, the more he’s dug his heels in.

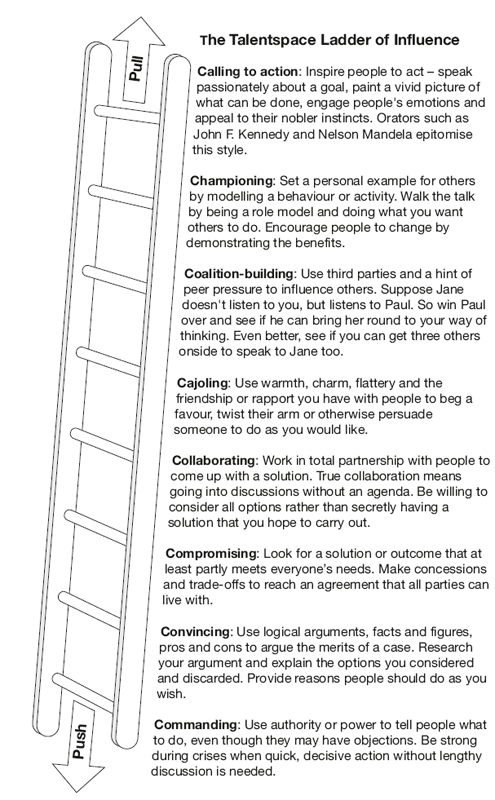

Telling people what to do rarely works. But you can still influence them and get them to change their minds. Generally speaking, you can either push people towards a goal or pull them towards it. You can push by telling people what to do, using authority or force of will or a rational argument to show them that they should or must behave a certain way. Or you can pull people towards your goal by inspiring and exciting them, and making them feel that they want to do what you suggest.

Take a look at the Talentspace ladder of influence below – a tool that I use at conferences and workshops to help audiences think about their impact and persuasiveness. The ladder begins at the bottom with ‘push’ influencing styles that are grounded in might and right, facts and figures and the right thing to do. Ascending to the top of the ladder you will find the ‘pull’ styles, which rely on lofty goals and ideas to inspire people into action. Of course we are capable of using all the different styles, but which do you think is your trademark style, the one that you currently use the most?

Most of us have a couple of dominant influencing styles. Many Low-Sensitivity people rely heavily on ‘Convincing’ and the other push styles towards the bottom of the ladder. High-Sensitivity people tend to rely too much on the pull styles.

Source: © Talentspace 2009, reprinted with permission.

No one style is inherently better than any other. If the fire alarm is going off and the building is filling with smoke, you don’t have time to sit around, discuss how everyone feels and gain a consensus on how to evacuate the building – you need to take command. Get everyone out.

But when your organisation is introducing a new computer system and a different way of dealing with customers, you can’t simply bark orders at people and expect them to do as they’re told. You need to talk through the benefits, answer questions, make changes or even concessions if employees can come up with better suggestions. Work together to devise the best way forward. Yes, you could force them to do it your way, but that would create resentment and bad feelings, possibly derailing future attempts to get them on side.

Over to you

Think back to a recent time when you had a disagreement with someone. Reflect on the following questions:

- What happened?

- Which style(s) of influence did you deploy at the time?

- What other style(s) could you potentially have used?

- How would you handle the same situation if it happened again?

Influential people are chameleons – adaptable, flexible. They switch tactics constantly, reading different people and nuances in situations and changing styles as necessary.

What works to win over a customer during a negotiation may not be appropriate to persuade your mother-in-law not to buy you some hideous ornament for your birthday. What works to rally support for a charity may not have the desired effect when what you want is a favour from your boss.

The next time you need to influence an individual or change the minds of a group, which style are you going to use?

Become your best: Adding influencing styles to your repertoire

Expand your range of influencing styles by looking around you for individuals who exemplify each of the different methods. Who is the epitome of ‘Call to action’ or ‘Collaborating’ or whatever else you want to get better at? Once you’ve spotted such role models, work out what they say and do that makes them so effective.

You may know some of these people in person or perhaps have seen them on television or read about them in biographies or the press. Politicians, public figures, even Hollywood actors are often great examples of how (and sometimes how not) to influence and persuade others. Study them, observe them, read about them and the results they achieve. Scrutinise their every word and deed to see what you can incorporate into your own repertoire.

Uncover your own assumptions

“Assumptions are the termites of relationships.”

Henry Winkler, actor

Say a friend or colleague lets you down. You emailed Paula last week asking her to book train tickets for Friday. She replied saying that she’d do it. But it’s Friday now and guess what? She hasn’t got the tickets. The facts are irrefutable – you even dug out the email exchange to check that she’d understood and agreed to your request. You’d be justified to point it out, even to tell her off for having messed up, right?

Well, maybe.

Become your best: Understanding how you attribute behaviour

If other people forget to do something, it’s because they’re lazy or careless. If we forget, it’s because we’re overworked or have other things on our minds. If someone else criticises us during a meeting, it’s because she’s trying to score points with the boss. If we point out a similar mistake, it’s because we think that there are genuine lessons to be learned.

Psychologists have known for a long time that we typically attribute other people’s mistakes to their personal failings, but attribute our own blunders to external circumstances. We give ourselves the benefit of the doubt, whereas we tend to find other people guilty straight away. But even when we think we know all of the facts, we usually don’t. We simply can’t know what other people were thinking, what they intended, what else was happening in their lives at the time.

Here’s the lesson: other people’s thoughts and intentions are invisible. You can never know what they’re thinking. You are, all of the time, making assumptions based only on what you think you’re seeing.

Without talking it over with Paula, you don’t yet have the full picture. Perhaps she did book the tickets but the travel company lost her booking. Or the computer system may have gone down so she couldn’t book the tickets. Maybe she did forget, but her daughter was taken into hospital at the beginning of the week. Or she was so inundated with work that she had been doing four or five hours of unpaid overtime every night for the past month. Perhaps she emailed you to say that she wouldn’t be able to book the tickets, but the message got lost in the system. Maybe she couldn’t book the tickets and she tried to tell you, but you were so busy that you didn’t have time to listen.

For any situation, there are many possible explanations. You can’t know all of the facts. So starting any difficult conversation with the ‘facts’ is likely to involve making assumptions about what actually happened. And that’s a sure-fire way to make other people feel defensive. Before you know it, you’re in a fully fledged argument, exchanging rash words, dredging up past misdemeanours and even engaging in personal attacks that may have little to do with what you actually wanted to discuss.

I’m not suggesting that you ignore the issue. Rather, think about your opening salvo, how you will approach the issue. Be clear that you are speaking only from your perspective and you don’t yet have all the facts. Position the discussion very clearly as a conversation – a mutual exploration and fact-finding mission – rather than a telling-off.

The best way to broach any potentially difficult conversation is to talk about your feelings, to say that you feel let down, angry, shocked or whatever else you might be feeling. People may dispute the ‘facts’, but no one can argue about how you feel.

Become your best: Bringing your feelings to the fore

You need to point out a mistake, offer someone criticism or confront someone’s behaviour. You get that you need to talk about your feelings, but here’s another tip: be sure to start your statements in the first person singular (‘I …’) rather than the second person (‘You …’).

Avoid saying, ‘You excluded me from that discussion last week so I felt disappointed’ because the other person could retort, ‘I did not exclude you from that discussion!’ Making ‘you’ statements assumes that you can read other people’s minds about their intentions. It’s safer to say, ‘I felt excluded from that discussion last week’, with the implication, ‘Regardless of whether you intended it or not, I felt that you excluded me from that discussion last week.’

Even when you feel that you have all the facts, choose to focus on your feelings. ‘You didn’t get the report out’ is very direct, abrupt, almost accusatory. Instead, begin with, ‘Can I share something with you? I feel rather disappointed and frustrated with a situation at the moment. Can I tell you my side of the story and see what you think?’

Talking about your feelings and inviting the other person to contribute gives you a much softer way into discussing the situation. Talking about your feelings allows you a much more conciliatory approach into difficult conversations.

Perhaps you’re not convinced. Most people hate getting ‘touchy feely’. I know a lot of people who would rather shovel cow manure than start a sentence with the words ‘I feel …’ Especially at work, you may think that it’s not appropriate to get into how you and everyone else feel.

But suppressing emotions just doesn’t work. If you try to put on a front, they’ll creep out anyway. We get cracks in the dam of our demeanour. Our emotions may leak into the tone of our voice, the set of our jaw, how we stand and hold ourselves. When we feel really strongly about something, angry words may fly or tears well up. Better to vent them in a controlled fashion by talking about them than pretend they don’t exist and risk them bursting out when you least expect it.

You still get to broach the conversation. But rather than assuming you’re right and the other person is wrong, you present the situation as an open-ended discussion in which you are simply trying to figure out what happened. Do that and you will get the best possible outcome.

Over to you

Have a go for yourself. Take a look at the following statements. At the moment they are potentially inflammatory comments that could ignite a confrontation, cause an argument. How could you turn them into invitations to jointly discuss the situation and find a solution?

- ‘Why did you point out my mistake in front of the rest of the team?’

- ‘You aren’t doing enough of the housework. On top of my job, am I supposed to be our housekeeper too?’

- ‘By continuing to argue against what the rest of us agreed, I think you’re being rude and disruptive.’

- ‘Your son has already put on so much weight because you’re letting him eat too much junk food.’

- ‘You promised that you were going to sort out the finances by the end of last week and you still haven’t done it.’

I’ll help you a bit. Here’s how I might rephrase the first one. Rather than make such an accusation, a better opener might be, ‘Do you have five minutes? Yes? I wanted to talk to you about the meeting this morning and get something off my chest. I felt really annoyed by something you said. I’d like to explain why I still feel annoyed and get your side of the story.’

How does that sound?

Now, I know you’re probably thinking, ‘That isn’t how real people talk!’

You’re right: most people don’t talk like that. But just because you don’t hear such language regularly doesn’t make it any less powerful. Mediators use this language. Psychotherapists and marriage counsellors use this language. Diplomats and negotiators use this language. A small proportion of savvy leaders do too. Why not take a leaf out of their books? What’s the worst that could happen if you try it? It doesn’t work – yes, but you’re no worse off and you can always go back to bludgeoning people with facts. But what’s the best that could happen if you try?

No matter what your level of empathy, you can hone it further. Expand your emotional lexicon. In the same way that you get better at putting on the green with practice, you can get better at judging the right phrases and approach to use with another person.

Make the most of yourself – for High-Sensitivity people

You have an uncanny sense of how other people feel. Your empathy and willingness to put others first means that you’re a great team player. That is a huge asset – at least some of the time.

I came across Polly and Shaun, 50:50 business partners in a start-up magazine publishing company. Polly is naturally high on Sensitivity. So when Shaun went through a tricky divorce, Polly was willing to take on some of his workload. When Shaun met a new partner and had a child, Polly again ended up taking on more of his workload. When the business struggled and cash was tight, she agreed to forgo her salary for a few months so Shaun could take a salary to support his young family.

Is Polly a team player? No doubt about it. But is she a doormat? Most of her friends have said on more than one occasion that she needs to stand up more for her rights.

People like Polly risk being less successful in their careers than other people. Research tells us that agreeable, High-Sensitivity people tend to earn less and progress more slowly up the ranks than their more straight-talking, Low-Sensitivity counterparts. I know, I know – there’s more to life and happiness than money. But if you want to clamber up the ladder of career success and earn the big bucks, be aware that the best-paid jobs sometimes require toughness and the ability to make the hard decisions. To tell it how it is, say ‘no’ and disappoint others, even kick ass on occasion. So this section gives some advice on how you can do at least a little of that.

Facing up to the downside of empathy

You avoid conflict and disagreement because you want to make people happy. You probably don’t mind putting their needs ahead of your own, even if it means more work and hassle for you. But what if putting their wants and needs first could be doing harm?

I see a pattern of behaviour developing when parents don’t take a stand and set rules for their children. Spending a week on holiday with friends Charlotte and Daniel, I was amazed at the behaviour of their children. The children frequently talked – or even shouted – over the adults. And Charlotte and Daniel let them get away with it. Their ten-year-old daughter was sullen when their mother asked her to take some of the dinner plates into the kitchen. She took a few through to the kitchen then sat down in a huff, declaring, ‘He only had to carry three plates into the kitchen, why should I have to do any more?’

In their desire to be loved by their children, Charlotte and Daniel (and many other parents) are indulging their children. They’re inadvertently creating me-me-me children who will turn into spoilt, selfish adults. As grown-ups, they will lack the give-and-take strategies to prosper in life.

The same goes at work too. Say a colleague is repeatedly turning up late for work and not doing his job properly. You know that he’s suffering in the wake of difficulties at home and feel for him. You’d be inhuman not to sympathise. But what if his poor performance is putting customer relationships at risk? What if the other members of the team get so sick of picking up the slack that they decide to look for new jobs?

Willie Walsh, currently CEO of British Airways, was a mere week away from his fortieth birthday when he became CEO of Irish airline Aer Lingus. The airline was losing £2 million a day. His first task was to announce 2000 redundancies – a third of the workforce. How did he feel about that?

People say to me that it must have been hard to do that, because a lot of those people were my friends. But it wasn’t, because I had no choice. Either a third of them went or all of them would have gone. It was that bad.

Sometimes you need to take a stand. To speak up when someone’s idea is misguided, unrealistic, even dangerous. To take someone aside when she makes the same mistake over and over again, never learning from it. What if someone repeatedly fails to deliver on his commitments, makes a racist or sexist comment, or takes advantage of a colleague? What if someone flouts an important rule, disregards health and safety concerns, even breaks the law?

Stuart Goddard, divisional managing director at an investment boutique, put it to me this way:

Good people management is like good parenting. You need to balance kindness with toughness. Sometimes you should let things slide, but other times you need to be a firm disciplinarian so the problem doesn’t get out of hand.

Polly Ford, owner of her own public relations firm, tells me:

You need to marry your heart with your head. Your heart may want to please people, but sometimes your head has to take action that’s in the best interests of the team.

Over to you

By not speaking up, you risk doing others a disservice. You’re assuming they’re too fragile to be told the truth.

Think about your own situation for a moment. If you were doing something that was ineffective, a bit silly or plain wrong, wouldn’t you want to be told? Say you cooked a dinner for friends and added far too much salt. Wouldn’t you rather know to avoid doing it in future? If you were sending paperwork to the wrong department at work and creating more work for people, wouldn’t you want them to say something? Or would you rather your friends and colleagues let you make the same old mistakes, time and time again, feeling more and more fed up every time you did it?

Putting other people’s needs first isn’t always a good thing. Identifying too strongly with their needs can harm the collective good or even them in the long term. So be careful if you have unruly children, friends or people in your team. How long are you willing to let them run riot?

“The art of leadership is saying no, not yes. It is very easy to say yes.”

Tony Blair, former prime minister

Consider the best for everyone

No one is saying that your level of empathy is a bad thing. It’s great that you can get into the heads of other people, experience the world from their perspective and feel how they feel. However, you mustn’t let your empathy stop you from making the tough decisions. Decisions that may leave colleagues without a promotion, without the fun projects or the bonuses they covet. Decisions that may leave your children without the bag of sugary sweets they want to take to bed. Or your friend without the £10,000 investment he wants for his dubious new business venture.

You probably struggle to see when such decisions are necessary. Your gut reaction is to say ‘yes’ to people, to give in to their requests, to put them first. But sometimes you need to step back, appraise the situation and not automatically put others first. Here’s a tried-and-tested technique to help you make the best decisions for everyone.

Become your best: Practising objective detachment

Objective detachment helps you to think about difficult circumstances from the perspective of a third party. What would an intelligent person who is not involved in the situation advise you to do? Imagine a judge in court listening to arguments and counter-arguments on behalf of a plaintiff and defendant(s).

Work through the following steps:

- 1 Write down the other person’s situation. Think of this person as a plaintiff in court, making some kind of request. Jot down a handful of bullets to capture the other person’s behaviour and situation – what he or she has said or done to date.

- 2 Write down your and others’ needs. These others are the defendants in this situation. But the first person you need to think about is you. What would you ideally like to get out of the situation? Then consider your colleagues, customers, family, friends, whoever. Your aim here is to take into account the collective good. Write a couple of sentences for each person or group.

- 3 Consider the plaintiff’s role. In other words, what is generally expected of a person who is an employee, a supplier, daughter, husband, boss? Would you expect most employees to turn up to work drunk? Suppliers to deliver their shipments late? Daughters to be rude to their grandparents? Your aim here is to maintain a distance between yourself and your current situation. Think about what the average person would expect of a person in that role.

- 4 Imagine a judge in court listening to the arguments and counter-arguments. What would a judge declare needs to happen in your situation? What’s the best solution for everyone?

By spending a few minutes setting your thoughts out on paper, you can weigh your options up properly and make decisions that don’t automatically put the other person first. But it only works if you use it! Having it at the back of your mind isn’t good enough.

If a friend or colleague catches you with a request, ask for time to think about it. By all means listen to the request, but avoid making a decision there and then. Say, ‘I need a little time to think about it. Give me X minutes/hours/days.’ Then take those minutes or hours or days to write down your thoughts, divorcing your immediate feelings from the right thing to do. If you allow yourself to be bullied into making decisions on the spot, you are much more likely to capitulate, to give in to other people’s demands and regret it later.

Over to you

Think about a person that you would like to be more assertive with. Perhaps something has happened in the past that you want to bring up. Maybe something is going on right now. Write down the answers to the following questions:

- What are the advantages of speaking up?

- What are the disadvantages of not saying anything?

- What’s the best that could happen if you speak up?

- When and where would be a good time and place to raise the issue with this person?

- What will you actually say? Write down the first few sentences you will actually use to broach the topic. Then recite them out loud a couple of times to get more comfortable saying them.

Tell it straight

The advantage of being a High-Sensitivity individual is that you’re good at talking about your feelings. As I advised Low-Sensitivity people earlier in this chapter, that’s the single best way to kick off a discussion when you want to give someone feedback.

That said, Low-Sensitivity people tend to be better at stating their case, at talking about their perspective. The challenge for many High-Sensitivity people is that they don’t like to assert themselves, to put forward their point of view. But it is easy to learn how.

Become your best: Giving effective feedback

When people are evidently going wrong, you need to speak up. Remember that you’re doing them a disservice by not giving them proper guidance. Criticism need not be confrontational or cataclysmic if you follow the ‘7 Cs’ of effective feedback:

- Clear. Prepare what you want to say ahead of time. Most people find it easier to deliver a message that they’ve thought about than have to think on their feet. Five minutes of planning is all it takes.

- Current. Give feedback as soon as possible after a situation has arisen. The longer you let it linger, the more ingrained the problem becomes. Effective feedback is timely, not left for months until the annual appraisal.

- Candid. You owe it to both yourself and the other person to be honest. If you feel a certain way about something, you should say so. Hiding how you feel means that you end up skirting around the issue and never resolving it properly.

- Consequential. Explain the consequences or impact of the situation or the other person’s behaviour. It’s not enough to say, ‘You are entering data into the spreadsheet incorrectly’. You need to point out how it affects you or other people: ‘… which means that I have to spend an extra hour rechecking all of the numbers before I can do my job.’

- Constructive. Pointing out what someone has done wrong is a start. But together you should aim to find a solution rather than simply use the mistake to beat someone up repeatedly. What suggestions do you have as to how the other person could behave differently in the future?

- Confidence-building. Effective feedback should aim to correct someone’s behaviour and resolve the situation, but a lot of it ends up making people feel bad about themselves. Instead, bolster the person’s mood and confidence by helping the individual to consider the feedback in the broader context of what he or she does well.

- Consistent. Be sure to treat all of the people around you equally. If you point out one person’s mistakes but not another’s, you will be accused of having favourites. So be consistent in applying the same rules to everyone in the team or family.

ONWARDS AND UPWARDS

Sometimes we need greater empathy; sometimes we need detachment. Remember that it’s neither better nor worse to be low or high on Sensitivity. Low-Sensitivity people could at times do with being more tactful; High-Sensitivity people need to be more direct on occasion.

Here’s a quick reminder of words and phrases that broadly distinguish people who are at either end of the spectrum.

| Low-Sensitivity | High-Sensitivity |

| Usually direct and to the point. | Usually diplomatic and considerate. |

| Good at confronting poor performance. | Good at making people feel understood. |

| Focus too much on the facts of a situation. | Focus too much on other people’s feelings. |

| May be criticised for being too blunt, abrasive. | May be criticised for dodging issues. |

| Too assertive – may be seen as aggressive. | Not assertive enough – may be seen as weak. |

| Need to talk about their feelings (‘I feel …’) more. | Need to consider the facts (‘I think …’) more. |

If you scored lower on Sensitivity:

- Recognise that few people are swayed by facts alone. Telling people the ‘right’ course of action is rarely enough to change their behaviour. Keep in mind the different – particularly ‘pull’ – influencing styles that you can deploy in persuading people to your way of thinking.

- Appreciate that most people – including you – make certain assumptions when they engage in potentially difficult discussions. Be sure to explain that you want to share your side of the story but you don’t have the whole picture yet.

- Get used to talking about your feelings. Pretending that feelings don’t exist means that they may burst forth anyway. The simple words ‘I feel …’ can defuse conflict and put you and others on a collaborative rather than confrontational footing.

- Play to your strengths for long-term success. Seek out environments in which your honesty and directness are appreciated. Find bosses and colleagues and friends who genuinely want you to tell it as it is and not as they want it.

If you scored higher on Sensitivity:

- Recognise that not speaking up can be more harmful in the long term than giving someone your honest opinion. Remember how you’d feel if you were doing something badly or making a mistake – wouldn’t you want to know?

- Consider how an objective third party would regard your situation. If you were advising a friend or a judge were appraising the state of affairs, what would they say needs to happen?

- Spend a few minutes working through the ‘7 Cs’ of effective feedback. Planning what you want to say helps you to get your message across assertively yet tactfully.

- Succeed in the long term by seeking out situations and organisations that allow you to work collectively and collaboratively. Avoid ones in which you will be constantly required to challenge people and fight your corner.