03

“I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”

Thomas Edison, inventor

When I met Richard Parks on my first day at university as a bright-eyed 18-year-old, I couldn’t have predicted that he would remain one of my closest friends today – nearly 20 years on. But I would never have believed anyone if they had predicted that he would also become one of my most successful friends. He laughed all the time and, to be honest, I thought he was kind of goofy at first. So how did he become one of the richest people I know?

Richard is currently an executive vice-president of a software business. Five years ago, he and his former business partners sold a previous business, netting him a pay-off in the mid seven figures. But what makes him a marvel is the adversity he has overcome through the years.

Having completed a degree and PhD in physics, he tried to find work as a university lecturer. He applied for over 200 jobs all over the world, but was knocked back every single time. To pay the bills he took menial jobs, working in a kitchen and then a newsagent. Only after 18 months did he give up hope of working at a university to take a job as a financial analyst for an investment bank.

When he and his wife were expecting their first child, the doctors diagnosed their daughter with a rare heart defect that needed extensive surgery at a specialist hospital 80 miles away. Richard and his wife sold their lovely house and rented a small flat to be near their daughter for the year and four touch-and-go operations to give their infant daughter the chance of a full life. It was during this gruelling life-and-death period that a downturn in banking led to him being made redundant.

Despite all of these setbacks, Richard has never been anything less than composed and resolute. He has always managed to get on with his lot in life. He has coped with rejection, his daughter’s ill health, redundancy, as well as the other day-to-day setbacks that we all experience.

How do some people suffer anything from minor hiccups to severe setbacks and manage to carry on? We can all think of people who never really got over a relationship break-up or those who still harbour bitterness over not getting a promotion or losing their job – even years down the line. No one could have blamed Richard if he had broken down, but he didn’t. Because he possesses the gift of resilience, which is both a personality trait and a quality that you can cultivate.

Your Resilience

Head back to Questionnaire 2 on page 6. Give yourself two points every time you agreed with one of the following statements: 1, 3, 6, 9 and 10. Give yourself two points if you disagreed with each of the statements 2, 4, 5, 7 and 8. You should have a score between 0 and 20.

A score of 8 or less suggests that you’re a Low-Resilience individual. A score of 14 or more suggests that you are a High-Resilience person. A score of between 10 and 12 suggests that you have average levels of Resilience.

Read through the rest of this chapter and pick out the sections that are aimed at your personality profile. Remember that your score is only a rough indicator of your true personality. Which end of the spectrum do you identify most strongly with? If you’re average on Resilience, you will probably benefit more from the advice aimed at Low-Resilience scorers – most of us could do with being more (rather than less) confident in the face of adversity.

What kind of person are you?

If you’re sensible, you may have a smoke alarm in your home. Some smoke alarms are incredibly sensitive, going off at the merest whiff of lightly burnt toast. But I remember living in an old house where the kitchen smoke alarm hardly ever went off. A friend once set a pan of pork chops on fire. Flames shot out of it, sending smoke billowing across the room, and still the smoke alarm didn’t make a peep.

Your level of Resilience is determined by your brain’s smoke alarm – its early warning system. A small almond-shaped structure in your lower brain called the amygdala looks out for potential threats. Once your amygdala spots a hazard, it sends adrenaline coursing through your veins, makes your heart beat faster and makes you feel tense, wary and prepped for fight or flight. This was all very useful to our ancestors – those primitive humans for whom even a rustle in a bush could have meant being eaten by a ravenous animal.

Low-Resilience people have alarm systems that go off a little too often; High-Resilience people have alarms that perhaps don’t go off quite as much as they should. Irrespective of how your system is wired, you can learn how to make better use of it.

The Low-Resilience person: your own worst enemy

You want to do a good job, be liked and be successful. But you worry about what could go wrong and you agonise over the mistakes of the past.

You know that your tendency to worry gets worse when the pressure’s on – perhaps when there’s a deadline or someone watching over your shoulder. Or if it’s a bigger challenge than you’re used to dealing with. You can’t help thoughts popping into your head, saying:

- ‘This is all going to go horribly wrong.’

- ‘Oh no, I shouldn’t have done that!’

- ‘I can’t do this – it’s too difficult.’

Your worrying can be a good thing though. You’re very aware of your shortcomings and you try to fix them. When people point out that you’ve done something wrong, you remember it. You make a mental note and try ever so hard not to mess up again.

Add to that your aptitude for spotting potential problems in projects and tasks. Other people may look at the future with rose-tinted spectacles, but you have a critical eye and can put bad ideas and initiatives out of their misery straight away.

You wish you could fret less, but you can’t seem to help it. In a way, you are your own worst enemy. You’re much more critical of yourself than other people are of you. You’re much more concerned about your work, your home and the state of the world than most other people. Looking back, you realise that you probably worried about some things that actually didn’t turn out so badly in the end. Wouldn’t it be great if you could worry a bit less and keep those roiling emotions under control? And learn to bounce back just that little bit more quickly?

The High-Resilience person: serenity personified

You’re the kind of person who is calm, composed and cool-headed. It takes a lot to faze you. Even when a customer is shouting and screaming at you about her missing shipment, or when your boss tells you that he’s got to make you redundant, you remain unruffled. Same goes at home too. Whether it’s your family or your flatmates who are getting worked up over the latest problem, you simply don’t feel the need to get upset, to overreact.

You probably lose your temper incredibly rarely; you hardly ever cry. Traits that make you great in a crisis. You don’t just tolerate stress – perhaps you even thrive on it? When everything is hitting the fan, everyone else depends on you. Because you’re the one who stays level-headed, keeping your emotions in check and thinking of the best way to get out of a jam.

While some people worry and see threats everywhere around them, you see the world as a benign place. Sure, bad things can happen. But most things turn out OK in the end, so why lose sleep over them? And if something bad happens, you know you can bounce back. After all, it’s not like most of the challenges you face are actually going to kill you.

Nor are you the kind of person to dwell on your mistakes or flaws. Sure, you may make a few mistakes and you’re not claiming to be perfect at everything, but why fret about anything? Life’s too short.

Make the most of yourself – for Low-Resilience people

The modern world rarely confronts us with anything that puts us in mortal peril. But if you’re a Low-Resilience individual, your amygdala is hypersensitive all the same. Your early warning system tends to go off a lot, alerting you even to modern-day ‘threats’, such as looming deadlines or giving a speech in public, the fear of being rejected by someone you like or having to deal with infuriating colleagues.

Even when there’s no actual threat to life or limb, your amygdala overreacts, unable to distinguish between a pressing deadline and a hungry animal out to have you for its dinner.

Choose action over avoidance

One way to cope with your overactive amygdala would be to avoid stressful situations. Never speak up at work for fear of ridicule. Never go on a date for fear of rejection. In fact, never set foot outside of the house because of all the terrible things that could happen to you. But avoidance – burying your head in the sand and hoping that life will go away – isn’t exactly a strategy for success and fulfilment.

Thankfully, science tells us that there is another route. You can inoculate yourself against life’s stresses. Doctors inject vaccines, small amounts of harmful viruses, into your body to help it defend itself against the big bad viruses. In exactly the same way, you can immunise yourself against stress by gradual exposure to the very situations that you fear.

Expand your zone of comfort

Do you find yourself avoiding situations in which you think that you might fail, look stupid or be criticised? Perhaps for you it’s speaking in public or networking with strangers, confronting a loved one or working through the company finances. It’s perfectly understandable to feel scared or put off sometimes. But if you want to grow your confidence and achieve more, you can.

We all have a comfort zone – a certain way of behaving that we feel happy with. The good news is that you can expand your comfort zone.

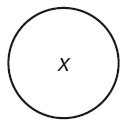

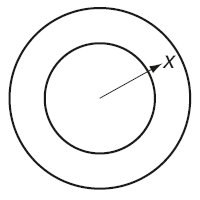

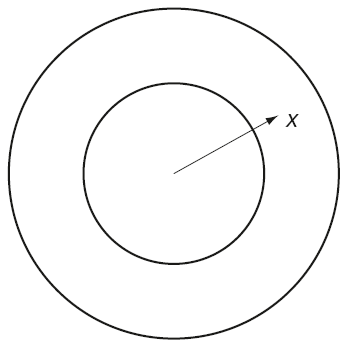

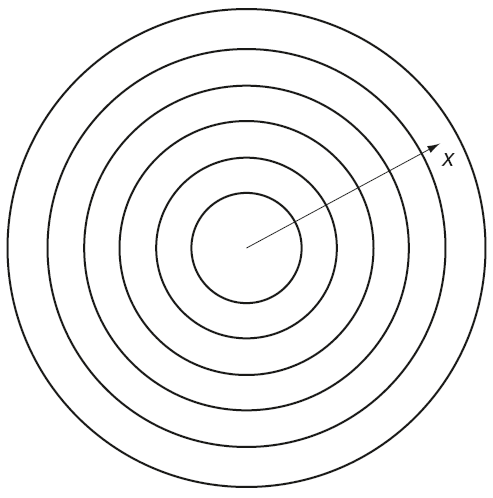

Every time you step outside of your comfort zone, your reach grows a little. Think of your comfort zone as a circle, with you stood in the middle. Outside of the circle is the zone of uncertainty. ‘X’ marks the spot where you’re standing, feeling comfortable.

Say you take on a small challenge, taking a tiny step out into the zone of uncertainty. Guess what? Your comfort zone grows to include where you’re standing now.

So what happens when you take another step, outside of your new comfort zone? Yes, your comfort zone swells even more.

Of course, one huge leap into the unknown would be darned scary, but that’s not what I’m saying you should do. Growing your comfort zone is simply a matter of taking a series of small steps, one step at a time. Do that uncomfortable thing a couple of times, and perhaps some more, until it becomes comfortable. Build up your confidence and comfort dealing with a challenge, and then move on. Take on even the tiniest challenge and you grow more courageous when facing the next one. Over time, your comfort zone grows and grows.

Say you’re scared of speaking at your team’s annual conference. Why not start by giving a five-minute speech in front of just one supportive buddy? Then add a bit more material and give a ten-minute speech to that same friend. Get that under your belt and move on to giving a speech to two friends. You may have to buy them lunch to persuade them to listen to you, but that’s OK. Then maybe give a quick update during your team meeting. By building up in small steps, you grow your confidence to do more.

Over to you

What could be better in your life? In what ways would you like to expand your comfort zone? Jot down three areas of your life in which you’d like to push yourself. We’ll come back to these in a later chapter.

- .......................................................................................................................

- .......................................................................................................................

- .......................................................................................................................

Create calm in the storm

Ever had one of those days when you want to scream?

Perhaps it’s the threat of an imminent deadline or your boss wants the whole report rewritten again. Maybe your babysitter has let you down at short notice when you’ve got a crucial get-together. Perhaps you simply have too much to do in too little time.

We all have so much to do in our busy lives, so no one can blame you for feeling overwhelmed occasionally. When you’re feeling worried or stressed, your productivity falls off the edge of a cliff. The anxious thoughts swirling around your head stop you from thinking rationally. You may blow problems out of proportion, fail to apply your creativity and make mistakes that you wouldn’t usually make.

Struggling on when you’re stressed is a waste of your time. When you can feel the tension rising, take five minutes to reboot your brain and let your rational operating system reassert control.

Become your best: Taking a time out

When you’re worrying or feeling snowed under, you can bet that your amygdala is firing up. But you can quieten it down by performing an easy rote task that allows your higher brain to snatch back control. The key is to persist with the task, ignoring the anxious thoughts that may be trying to pop into your consciousness. Focus your whole attention on the task, concentrating on it as intently as you can. Here are some examples of ways you can override the disruptive emotions running through your head.

- Write in detail about a neutral or pleasant topic – for example, a description of your house or a recent holiday.

- Do some arithmetic – subtract 7 from the number 193 until you reach 0. Either write your answers down or – to challenge yourself further – do it in your head.

- Replay a favourite song in your head. Hear the melody and sing the words in your head from start to finish. Better still, plug into your iPod or even sing out loud if you’re alone.

- Take slow, deep breaths. Breathe in through your nose to a slow count of four and breathe out through your mouth to a count of four.

- Pick up a dictionary and write out sentences incorporating words you’ve never come across before.

Give a name to your emotions

When your emotions feel like a runaway train, an unstoppable juggernaut of anxiety that threatens to derail all rational thought, you can put the brakes on.

I recently did a live interview on the BBC’s Working Lunch programme – a lunchtime business affairs show. Moments before I was due to go on, I was hit by a pang of nerves. My throat went dry and I started coughing. Perhaps because I was going to be on screen with Andy Bond, chief executive officer of mega-retailer Asda. Or maybe it was the thought of speaking live to several million viewers.

But I told myself, ‘I feel nervous.’ And I asked myself, ‘Why?’

Seconds later, I was answering questions on live television and I felt great again.

Cognitive behavioural therapists have known for a long time that quizzing yourself about how you’re feeling can help to quell negative emotions. Whether you’re feeling depressed over a break-up or angry with a friend who has let you down, you can control your emotions.

Simply name the emotion that you are feeling. Stop whatever else you’re doing and say to yourself, ‘I feel panicky’ or ‘I am feeling guilty’ or ‘I am feeling …’ whatever else you may be feeling.

Become your best: FADE tension away

Naming the emotion you’re feeling is a start, but you can do much more. This is a shortened version of a technique from my book, Confidence: The art of getting whatever you want (Prentice Hall, 2008). To get the most out of this technique, grab a pen and paper and take 60 seconds to write down your thoughts:

- Feelings. Name all of the moods and emotions that you’re feeling. Write down, ‘I am feeling …’ – sad, jealous, afraid, resentful, uncertain – all of the emotions you feel.

- Actions. Write down how your feelings are affecting your actions, your behaviour. Are your hands trembling? Are you close to throwing in the towel or bursting into tears?

- Defects. Quiz your feelings and actions and ask yourself if they’re appropriate and productive. Imagine your best friend is giving you advice – what would he or she say about how you’re feeling and behaving?

- Evaluate your feelings again. Ask yourself how you’re feeling now. Do you feel better?

How you feel and behave is determined by a constant battle between your rational and emotional minds – the higher brain versus the lower brain. The mere act of naming the emotions you’re feeling can begin to calm an unruly amygdala. The more you quiz the turmoil in your head, the better you feel. Going through the mental rigour of analysing your feelings allows your rational side to begin to conquering your emotions.

But you have to do it to get the benefits. Understanding how the technique might work in theory is not the same as putting it into practice. You have been warned!

Improve your persuasiveness

How many times do you tell your colleagues what’s great about their ideas or compliment your loved ones? How often do you point out the positives in a situation before discussing the negatives?

You have a particular gift, which is to sense what could go wrong. While High-Resilience people blithely overlook potential problems, you’re good at putting bad ideas out of their misery. That means, however, you may be seen by people – colleagues, clients, friends and family, your boss – as unsupportive, too negative, overly critical, unnecessarily pessimistic.

To make sure that I’m not being too harsh, I asked for a second opinion. Angela Mansi is a highly regarded coach and a senior lecturer at Westminster Business School. She has a similar warning:

You are highly alert to potential threats and problems, which can be a strength, but being too focused on these means you might fail to see the positive aspects of new situations. Certainly, others may see you as overly critical.

You don’t see yourself as a pessimist – only a realist. You see the world how it really is and not through the rose-tinted spectacles that others see it through. Only problem is, the rest of the world doesn’t appreciate a critic.

Think about it for a moment. Who are the people you value most in life? Are they the ones who support you, help you to focus on the positives and make you feel good? Or the ones who remind you of your flaws, tell you about your mistakes and point out how your plans won’t work?

No matter how good your intentions when you point out problems, I guarantee you that few people will thank you for doing it. People shun critics like they shun the arrogant office bore. People start to see you as the killjoy, the one with the ‘can’t do’ attitude. They begin to expect the words coming from your mouth to be critical or disapproving, so why bother to listen at all?

I’m not saying you should pretend to be a sunny person who sees only sweetness and light in the world. All you have to do is stop making negative comments and start asking questions. Rather than pointing out problems, look for solutions.

How much positivity is enough?

Emeritus Professor John Gottman at the University of Washington has spent decades analysing married couples and he’s found that he can predict with 90 per cent certainty whether a couple will divorce or still be together ten years later. His finding? That flourishing couples make positive statements five times as often as they make negative comments. In contrast, couples that later ended up hitting the divorce courts made only one positive comment for every negative comment.

Similar work has looked at successful teams and their less successful counterparts too. Researcher Marcial Losada compared high-performing work teams to teams that were less successful. After observing 15 such teams, he found that high-performing teams tended to make three times more positive than negative comments, whereas less successful teams made far fewer positive comments for every negative comment.

Avoid negative language, such as ‘But …’, ‘I can’t see how …’, ‘I doubt it’ or ‘That won’t work because …’ Instead, replace it with constructive questions that stimulate further debate and make people think:

- ‘That’s a fascinating idea. How would that work?’

- ‘Let’s brainstorm ideas as to how we can …’

- ‘That’s an interesting idea. I think it will exceed our budget, but what else could we cut back on if we want to do this?’

- ‘What if we … ?’

- ‘Are there other ways of looking at this?’

Reprogram your perspective

What do you pay attention to? I never used to notice dogs until our household gained a dog over the summer. He’s a schnauzer and we’ve called him Byron. Now that we have him, I notice dogs everywhere and I seem to spot different schnauzers at least a couple of times a week.

So what’s changed? Are there suddenly more dogs – particularly schnauzers – in my part of town? Or is it that my perspective is now more attuned to dogs?

We all respond to the world not as it is but according to the way we perceive it. You can tweak your perspective depending on what you look for.

Two people can see the same circumstances as either a disaster or an opportunity. I recently worked with a large group of managers who had been made redundant. Many of them had been working for the company for over ten years, but the new owners of the organisation decided to shut down the entire department. I was brought in to offer ‘outplacement counselling’ – practical support with CVs and interview techniques to help them find new jobs as quickly as possible.

Some of the managers were upset. Several had voices clogged with emotion; a few were on the verge of tears. Quite a few of the hardiest managers, though, saw it as an opportunity. One manager, Neil, said that he’d been doing the job for far too long anyway. He saw it as a chance to do something fresh. For many years, he’d been toying with working in forestry and land conservation. Another, Georgiana, was intrigued by the idea of life coaching, of helping others to find their way through difficult times.

Whatever your current outlook on life – whether it’s pretty neutral or extremely pessimistic – you can reprogram your perspective. Noticing the negatives in life is nothing more than a bad habit that people fall into. High-Resilience people edit out their failures and concentrate on their successes. So can you.

Become your best: Looking for positives

This is a simple yet incredibly powerful technique for calming your unruly amygdala. Buy a diary and, at the end of each day, write down at least three successes, achievements or positive moments. Perhaps it’s the comment you made in a meeting that made a colleague nod in agreement. Maybe it’s the fact that you complimented a friend on a new outfit and made her feel good. Or simply that you got to work early enough to enjoy a coffee and muffin while reading the newspaper before the first meeting of the day.

High-Resilience people play back successes big and small all the time. They replay them, share them with anyone who’ll listen and keep mulling them over and over again. No wonder they have such a confident mindset: they focus so tenaciously on their triumphs.

So look for your successes. Anything. The only criterion for inclusion in your list is that it’s important to you. And when you start to look out for three a day, you may often find that your list runs on and on.

You can choose to feel revitalised rather than run down. It really is up to you.

I’ve been working with Ewan, who started using this technique. He sent me an email saying, ‘On trying this exercise the other evening, I noticed so many things to be pleased about! It goes to show that we can unwittingly neglect the positives in life, only noticing the negatives.’

When you start to see things differently, you think differently, you feel differently, you act differently. Looking for three or more successes a day will only take a few minutes. Remember what I said in Chapter 1 – that many of the techniques in this book are small tweaks that get big results? This is one of them. In fact, the University of Pennsylvania’s Professor Martin Seligman, one of the world’s top psychologists, found that using the ‘three good things’ trick for as little as seven days helped to reduce worry and anxiety for up to six months. Pretty amazing, right?

Learn to let go

“Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

Courage to change the things I can,

And the wisdom to know the difference.”

Reinhold Niebuhr, pastor

Worry is constructive if it spurs you into action, if it makes you prepare for a situation, deal with its aftermath or put in place preventative measures for the future. But worry can be destructive if it merely dwells in your thoughts, causes your mood to plummet and stops you from getting on with your life.

So focus on what you can change and forget the rest.

If an issue is preying on your mind, set aside a limited amount of time to worry about it. Allow yourself say 10 or 20 minutes to think about it and make plans. What can you do about it today? What actions should you get down on a piece of paper to do tomorrow or next week? Who can you talk to about it?

Once you’ve done that, let the matter go. Move on to a different activity, a new task. Let go as if you’re a positive person and you may eventually become positive and confident to boot.

Make the most of yourself – for High-Resilience people

If you are High-Resilience, you are the envy of many people. When people around you are panicking and saying, ‘It’ll never work’, you forge on regardless. You shake off criticism and negativity. And even when things do go wrong, you bounce back so, so quickly. All this means that you come across as self-assured, poised, confident.

But that very self-belief can be double-edged. Others may wrongly interpret your confidence as arrogance. I’m sure you don’t think that you’re better than other people, but others may feel you inadvertently shrug off criticisms that are actually worth hearing. So the question is: do you ask for enough feedback and take on board sufficient criticism to keep your life and career on track?

See yourself as others see you

I read somewhere that one of the executives at the Oracle Corporation, a software company in California, once said of his CEO Larry Ellison, ‘The difference between Larry Ellison and God is that God doesn’t believe he is Larry Ellison.’

This is very amusing, but you can see how there’s a fine line between confidence and being seen by other people as arrogant. Between shrugging off unhelpful, negative comments and ignoring constructive criticism.

When was the last time you were on the receiving end of criticism that changed the way you behave?

I helped the managing director of a mobile phone manufacturer to interview a handful of candidates for the position of sales director. The MD wanted to hire someone who could take constructive criticism. So I asked all of the candidates the same three-part question: ‘When was the last time you were criticised? What did that person say? What did you do about it?’

One of the candidates, a charismatic manager with over 20 years’ experience of corporate sales, struggled with the question. ‘I can’t remember a recent time.’ So I rephrased the question and asked, ‘When was the last time you made a mistake? Could you tell me about that?’

Another pause. He finally came up with an example – that had transpired five years ago.

He honestly believed that he hadn’t been criticised or made a mistake in five years! That didn’t surprise me though. I had asked all of the candidates to complete a personality test and his results showed he had extremely high levels of Resilience.

No one is perfect. No one is so good at their job and marriage, pastimes and friendships that they are above criticism. High achievers intentionally seek out feedback. They are hungry to hear the bad news. They see criticism as a gift rather than a burden because it allows them to understand their blind spots and fix their flaws.

People don’t always tell you what they’re thinking. Just because they don’t say anything doesn’t mean they wouldn’t like you to change. So make it a habit to seek feedback from the key people in your life. When a project is over, ask colleagues or customers what you could have done better. Ask your boss once every month or two how you could do your job better. Ask your partner how you could be more helpful around the house or a better parent.

Become your best: Ask for the truth, the whole truth

So many people can’t take criticism – they go ballistic or sulk when they receive feedback on how they’re doing. Unsurprisingly then, many of the people in your life won’t want to give you honest feedback. Apart from your boss and perhaps your partner, most of them would rather give you positive strokes than incisive feedback about what you don’t do so well. Even if you beg for candid opinions, you’re probably going to get sugar-coated answers.

The best way to find out what people really think of you and how you could improve is to ask for anonymous feedback. Ask a dozen people who know you well to write letters to you. Tell them to type the letters and send them to you anonymously. Knowing that they won’t have to deliver bad news to your face, you may get a much franker picture of how you come across.

Choose your own questions or ask the following:

- What do I do well that I should not change?

- Are there any aspects of myself that I have trouble seeing?

- What could I do differently to be more effective?

When you receive the replies, be sure to look at the common themes. One person mentioning an issue may not be a big deal, but if two or three people mention it, you’d better take notice.

Give thanks for a poke in the eye

Once upon a time, the chairman and owner of a consulting firm that I worked for – I’ll call him Jeremy – decided that we should all give each other written feedback. We each chose four people and asked them to give us feedback on three questions:

- What good behaviours should I start doing?

- What bad behaviours should I stop doing?

- What good behaviours do I already do that I should continue doing?

I found the exercise incredibly instructive. This was way back in the early days of my career and I’d never received such blunt, honest opinions. I didn’t like a lot of what I read about myself. But I decided that if someone had written it to me, it was probably true. (I now use this start, stop, continue framework a lot in my work. You could do worse than adopt it too.)

At the same time as I got feedback on me, several senior people asked me for upward feedback. And two stood out. One of them, Kathleen, stopped me in the corridor and said: ‘Rob, I realise you’ve only been working here for a few months, so I appreciate you sticking your neck out to tell me what you really think. Thank you.’

Jeremy set up a formal meeting in which he spent an hour telling me why I’d got the wrong end of the stick. He used phrases such as ‘What you don’t understand is that …’ and ‘What you don’t see is that I do actually …’ He discounted or rationalised every comment I had made about him. Duly chastened, I learned never to criticise him again.

But what’s more fascinating is what happened to Kathleen. She eventually left the firm to found a business that is now several times larger than Jeremy’s. I’m convinced that at least part of her success was down to her willingness to take on board constructive criticism. The lesson: be more like Kathleen, less like Jeremy.

Become your best: Accept feedback with good grace

Say you receive feedback that is a shock – awful, disappointing, completely unexpected. You don’t agree with any of it. How should you respond?

The only response you should give is to say, ‘Thank you.’

Nothing more. Those two short words show your appreciation for the fact that people have taken the trouble to give you honest feedback.

Avoid at all costs trying to explain your behaviour. You don’t have to take the feedback on board – you can ignore it if you like – but don’t try to argue or justify yourself. No matter how you dress it up, your words will sound like excuses.

When someone offers you their opinion, what they are thinking is, ‘Here’s what I think you can do differently,’ not ‘I wonder why you are the way you are.’ You have to respect the fact that other people have the right to an opinion, no matter how badly they may have misunderstood the situation or misinterpreted your actions. So don’t try to explain how the situation arose. Don’t talk about extenuating circumstances or that they don’t understand the pressure you’re under.

No matter how softly you couch it, saying anything other than ‘thank you’ cuts off future constructive criticism. And I can guarantee that you will only come across as defensive or in denial. As sassy best friends sometimes say in the movies, ‘De-nial ain’t just a river in Egypt, honey.’

So. Shut up. Listen. Swallow your objections. Say ‘thank you’ or, if you must say more, say something like, ‘Thank you. That’s a lot to take on board, but I will give it some thought and see what I can learn from it.’

Enough lecturing. Now go put it into practice.

Show that you care

I coached a banking executive who was the poster boy for High-Resilience. Calm, cool and superbly collected, he never lost his temper or let the pressure of work get to him. I asked him if this was ever a problem and he said that it wasn’t.

‘Oh, but my wife hates it,’ he conceded after a little thought. ‘When she’s annoyed about something, she’ll yell at me and want a response. But I go quiet and let her get it off her chest. The fact that I won’t argue back makes her even angrier. She accuses me of bottling up my emotions, of refusing to say what I think. I’m not. She can’t understand that nothing ever bothers me enough to get worked up.’

If you’re a High-Resilience individual, you must understand that you are in some ways unusual. You may hardly ever feel stressed, but most other people experience more stress than you. Seriously. Very little gets to you, whereas a lot more bothers the people around you.

If you’re not careful, you could come across as emotionless, unfeeling – like the cold and calculating Mr Spock on the Starship Enterprise. So don’t be too quick to dismiss the predicaments that other people face. To you it may seem trivial or eminently fixable, but to them it may seem like the end of the world. Reading the sections within this chapter on how Low-Resilience people see the world may help you to appreciate their side of the story. Be sure to show that you care, that you understand – even if you can’t personally imagine what the fuss is all about.

ONWARDS AND UPWARDS

Remember again that Resilience – like all of the personality dimensions – is a continuum. Yes, a score of 16 may put you into the High-Resilience category, but even more so if you score 18 or 20. The same goes for Low-Resilience scores too – 6 may be low, but 2 or 0 is very low.

So you may be either high or low on the scale. You can be very high or very low – or a blend of the two. To help you remember the broad differences, here’s a brief summary of words and phrases that distinguish Low-Resilience from High-Resilience.

| Low-Resilience | High-Resilience |

| More tense and worried than they like. | Usually calm, composed. |

| Spot problems in situations. | See only opportunities. |

| Very critical of own performance. | Not very critical of own performance. |

| Sensitive to hazards and danger. | May not notice hazards and danger. |

| Agonise over mistakes and setbacks. | Bounce back quickly. |

| Take on board negative feedback. | May not seek out enough negative feedback. |

If you scored lower on Resilience:

- Look for gradual ways to expand your comfort zone. Avoidance isn’t a strategy. Courage fuels itself – be sure to take small, courageous actions every day.

- Take time out and analyse your feelings when stress is getting on top of you. Look for the positives at the end of every day. Negativity is nothing more than a bad habit that you can reprogram.

- Your effectiveness with other people is governed by how they see you. Aim to ask questions rather than point out problems so that other people find you less negative.

- Have a look at another of my books, Confidence: The art of getting whatever you want (Prentice Hall, 2008) – it’s packed with a ton of other tools and techniques like these if you want to take your confidence up, up and away!

If you scored higher on Resilience:

- Make regular efforts to gather feedback on what you could do better. Just because people don’t tell you doesn’t mean they think you’re perfect!

- Accept that other people may see you differently from how you see yourself. Respect the fact that they are entitled to their point of view. You need only say ‘thank you’ for any feedback: trying to explain your point of view could make you appear defensive.

- As so little bothers you, be careful not to come across as cold and unfeeling. Read the descriptions of how Low-Resilience people experience the world and try to get a glimpse into their concerns.