A few simple money-saving ideas to get you started

I know nothing specific about your particular financial circumstances but I am sure that the money you currently spend on financial services and products is not being spent to your best advantage.

The first money-saving rich trick I want to give is one we have mentioned already: avoid borrowing your own money and paying for the privilege.

For those of you still shaking your heads and thinking: ‘Don’t be ridiculous, I would never do that!’, assume that you have taken out a 9% loan (for, say, £20,000, over five years) to buy your car. In isolation, this is a very good deal. Generally, such debt is on an unsecured basis, linked to a depreciating asset, so 9% in such an environment is not too high a price. Now, two years later, another adviser suggests that you save towards the cost of your children’s future education (and so you are paying £300 per month at present). The advice is to do so via a long-term deposit-type vehicle with a large financial institution. Again, viewing this in isolation, a 3% guaranteed return with no risk to your capital, from a financially secure source, is also a good deal. In isolation, both financial decisions are good ones; both advisers have done their jobs effectively and within their respective compliance regimes.

In this scenario, you would be better off if you stopped saving money and, please excuse the pun, accelerated your car loan repayments. You would save thousands in interest payments, and could return to saving money when the loan has been paid off. The example below, taken from a real-life situation, illustrates how you can ensure that your money is working for you, and not for the institution.

Example 1

Borrowing and saving

A car loan was taken out two years ago for a total sum of £20,000, which is repayable over five years and charged at an interest rate of 9%. The monthly cost of servicing this loan is £428.49.

The total cost of this loan, over the five years, is £25,709.40 (£428.49 × 60 months) and, after two years , the borrower still owes capital of £13,015 which, with interest, will cost £15,425 to repay.

Two years after the car loan was negotiated, the same person decides to save £300 per month in a deposit account and receives 3% per annum interest. In the next three years (the same period as remains outstanding on the car loan), he will earn £514.38 in interest on his savings.

Instead of saving the £300, what will happen if he ‘invests’ that money into the car loan, paying £728.49 each month? Paying more off the loan each month will shorten the repayment term – in this case, reducing it from the remaining 36 months to only 19 months.

The cost comparisons of this action are:

Overall cost if loan left untouched:

£428.49 × 36 = £15,425.64

Overall cost if loan accelerated:

£728.49 × 19 = £13,841.31

By ‘investing’ the additional £300 each month in the car loan, the borrower saves interest payments of £1,584.33 (the amount not paid out on the car loan), while losing only £514.38 in interest foregone on the deposit. The net gain of £1,069.95 is equivalent to an annual return of 20.3% on the £300 per month ‘investment’.

And the benefits are even greater over the longer term as, in this example, the borrower was also trying to make provision for his children’s education. By investing the £300 each month in the deposit account and maintaining the car loan repayments on their normal schedule, the deposit balance would be £42,027.23 after 10 years. But, by paying off the car loan early and returning to saving money when this is done and then paying £728.49 per month (car loan payment + saving of £300), he will accumulate a total of £68,182.69 in the deposit account in the 10 years, some 62% more than if the current structure is allowed to continue.

This example shows that, if you pay attention to everything going on in your financial world, you can massively increase the value for money you’re getting in both the short term and the long term.

Another rich trick it also illustrates is that, once you get used to paying out a specific monthly amount, you should continue to pay out the same amount, even after the original debt has been cleared, since this will add considerably to your financial freedom. Most people, once the loan above had been repaid in full, would simply spend the £428.49 per month that’s now available on more ‘stuff’ – since lifestyle spending always rises to meet available income, if you allow it to do so.

You can see that a simple review and restructure of existing investment activities can make you wealthier. You need to review everything you have done in the past – and I mean everything. Placing money on deposit and borrowing money to buy consumer items are two areas where most people make expensive mistakes. Let’s take a look at each in detail.

Deposits

I cannot remember where I read this, but it is said that, in the UK, you are more likely to get divorced than to change your bank. Even in Ireland, where divorce rates are lower, the same principle applies. You can be absolutely sure that your bank knows this and will use it to its own advantage.

In my experience, when anyone has a lump sum to deposit, it typically ends up in their existing bank and they take whatever rate the bank says is available. There are two problems with this approach:

- It is rare that an ordinary clearing bank will offer the very best rate on the market. Such institutions are generally extremely large, with heavy fixed overheads, such as staff and a branch network, and demand a higher margin than a smaller institution. This means that they offer less in returns to their customers than others.

- The investor does not haggle, but simply takes the first price that is offered. I do not know why most people believe they cannot haggle when it comes to financial products. I know people who will haggle over the price of everything but money. My advice is to haggle your socks off. The rich haggle and it will pay dividends.

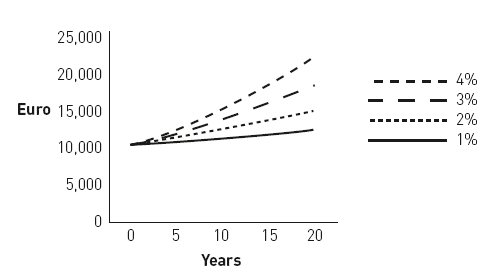

At the time of writing, interest rates are low, yet smaller deposit-takers are offering rates of 1% and, in some cases, even 2%, more than their high-street competitors. A 1% or 2% increase in annual returns may seem small, but it may be an effective 100% or greater increase in returns. And even greater gains are to be made if you are willing to commit your money for a fixed term. But let’s look at what an increased return can achieve for you in the longer term. In Figure 1, I’m going to look at the difference in future capital, over different timeframes, for an investor with £10,000 to place on deposit.

Figure 1 The future value of £10,000

* All figures rounded up or down to the nearest £5.

As you can see, reasonable increases can be enjoyed if you are willing to haggle over price. For example, over five years, getting 2% per annum instead of 1% per annum increases an investor’s wealth by £530 – or, expressed another way, by almost 104% (the return at 2% is £1,040, 104% of the return at 1%, which is £510).

I have not taken tax into account; suffice it to say that the after-tax returns will be just as improved as the pre-tax figures illustrated here.

Consumer debt and credit cards

The rise in popularity of the credit card and/or store card, along with other forms of consumer goods finance has had the most profound influence on the distribution of wealth in the western world. The ease with which such credit is made available has enhanced its popularity as a method of raising finance, while the rates charged have actually served to make the banks and major stores richer and you, the consumer, poorer. This type of debt should be repaid in advance of any other.

Interest rates can be 17%+ per annum. At the time of writing, my own credit card charges me 17.1% per annum in interest on outstanding balances – although, as you might suspect, I don’t carry long-term outstanding balances. To put these rates in perspective - it means that an item purchased for £1,000, that you pay for over two years, actually costs you nearly 19% more. To repay £1,000 over two years, at 17% per annum interest, will cost you £49.44 per month or £1,186.56 over the term (£49.44 × 24 months). So you can see that paying an interest rate of 17% actually increases the real cost by considerably more than 17%. At £1,000, your purchase may well be value for money; at 19% more, it is likely that you are simply paying too much.

Of course, many of you reading this do not need me to point out the obvious. We all know that credit cards and other such cards are expensive. Why is it then that you still have outstanding amounts on your card (or, in some cases, cards)? I mentioned at the start of this book that you would have to change some of your beliefs and opinions about money to achieve financial freedom. But simply changing beliefs is not enough; you have to change the way you act too. Instead of choosing the easy option and, when your next credit card statement arrives, simply paying the minimum, pay it all! Organise an overdraft or loan, if you have to. After all, these can be half the price, if not less, of credit cards. Then, once it’s all paid off, get rid of the credit card. Of course, they are handy and more secure than carrying cash but they stand between you and your financial goals. Replace them with a charge or debit card, which is just as handy and secure, but which is automatically repaid from your bank account each month (this means that you never run up long-standing balances on which you pay continuing interest).

We have all been allowed by the lenders to think that we can have the trappings of wealth before we are wealthy. Easy access to debt on credit cards, car finance, personal loans for holidays, allows us to enjoy things immediately without stopping to count the cost.

The true cost: think about the costs, benefits and risks

To make any financial decision to your best advantage you need to be in possession of three vital pieces of information:

- the costs

- the benefits and

- the risks.

So, if you are really serious about being like the rich and achieving your goal of financial freedom, then you need to identify each of these when making any financial decision, whether that’s spending, saving or investing money. In truth, our lack of financial education, combined with the complexity of the financial system, means that we very often make financial decisions thinking we have the information, when we really do not.

Let me give you an example of what I mean. I know I am labouring this point, but it is one of the most important I make in this book because if you get your consumer debt under control, your route to financial freedom will be far easier. I want to look at how you fund the purchase of a car.

Ever since it first appeared, the motorcar has been a sought-after status symbol. Why do you think the rich have such nice ones? Not only are the manufacture, sales and maintenance of motorcars multi-billion-pound businesses, but they have spawned other multi-billion-pound businesses such as car accessories, car magazines and model cars. We seem to be infatuated with the motorcar and the purveyors of credit know this all too well.

When my father was in his early career, back in the 1950s, the acid test as to whether he could afford a car or not was: ‘Do I have the cash?’ Somewhere between then and now, the car manufacturers and the banks have convinced us that the question is: ‘Can I afford the monthly repayments?’ This new attitude has served the manufacturers and banks very well indeed. The problem is that the true cost of buying a car does not form part of the decision-making process, principally because most of us have no way of calculating that cost. The following example outlines the true cost.

Example 2

The true cost of buying a car

Assume that the car has a retail price of £30,000 and that this amount is borrowed over five years at an interest rate of 8%.

The monthly repayments on the car loan will be £626.14.

So the overall cost of the £30,000 car is (£626.14 × 60) = £37,568.40.

But, that’s not the true cost of the car. You pay this money out of taxed income, which means that you will have had to earn more in order to pay the tax too. The personal income tax rates you pay on your income will dictate the true cost. For illustration purposes I have assumed two simple rates of 20% and 40%; your cost may be higher or lower than these, depending upon your top tax rate.

So, the actual cost of your car, from your gross (that’s your salary before tax) income, is £782 per month for five years if you pay a 20% tax rate and £1,044 per month if you pay the higher rate. Putting it another way, for a person earning £40,000 per annum, agreeing to this loan means pre-spending between 23.5% and 31% of each of the next five years’ income before it is ever earned.

And that’s still not the true cost of the car, as you could have invested the £782 or £1,044 each month over the five years without any tax liability whatsoever (see Chapter 4 for details), instead of buying the car. And, assuming that such an investment achieved a 5% per annum return, it would have accumulated in five years to between £53,400 and £71,300.

The decision to buy the car has meant that you are £53,000/£71,000 less well-off at the end of the five-year period than if you had invested the money instead.

Of course, if you really need to buy a car, then you have no choice but to incur this expense, unless you have the cash. However, a huge percentage of new cars are bought by people who already have a car and who are trading it in to buy a newer, flashier model – these people have a choice. Either way, my point is that the purchase of a car (or other major item) should be made in the knowledge of its true cost. So, the next time someone asks what your car cost you, use these figures to calculate the true cost. If your car was bought (with 8% finance) for £15,000, then its true cost was more like £26,700/£35,650; if it cost £60,000, then its true cost is £106,800/£142,600. This is the amount of money, based on the assumptions outlined earlier, that you would have accumulated had you chosen to invest towards financial freedom instead of purchasing the car. All other figures will adjust proportionately.

Earlier, I wrote about the need for you to change some of your financial habits and there is no doubt that the habit of funding the purchase of luxury consumer items with short- to medium-term debt is one of the worst you can have. Resolve to stop it today. Where possible, accelerate the repayments on any existing consumer debt and save yourself thousands in interest payments. In the future, do not buy these items until you can afford them – that is, until you can buy them the old-fashioned way, by paying cash. And the next time you are tempted, for there is nothing more sure than that you will be tempted, remind yourself of the real cost of these items when bought with consumer debt – hopefully, that will keep you focused.

Most people, when they see the car loan numbers for the first time, are shocked. They simply did not realise the true costs of the transaction, and so made a decision without one of the three vitally important pieces of information. I am not for a moment suggesting that you immediately become a whiz at financial calculations, but you can ask questions that ensure you get the numbers before you make a decision. When you know the costs, you can compare them to the benefits and make a fully informed decision.