‘He that has eyes to see or ears to hear may convince himself that no mortal can keep a secret. If his lips are silent, he chatters with his fingertips, betrayal oozes out of every pore.’

Sigmund Freud

We’re going to look at the signals given out by our limbs in this Lesson. As you’ll see, so much of our body language is conveyed through the hands, arms, legs and feet. We’ll also look at the various displacement activities and self-comfort gestures that are associated with our limbs and how they leak information that gives away our true feelings. Please remember these two terms, which are widely used in body language vernacular. They form the basis of recognising signals that you may see and ones that you are sending out to the other person. They represent the key to your mind-reading skills – an indication of what internal thoughts are being processed by the other person (and you).

Hands

We’ll begin with the hands, which are probably the most spontaneous of all our body parts. We use them to greet, illustrate points as we’re speaking and generally express the emotions that we’re feeling. We’re hard-wired to use our hands in tandem with our speech. In fact the number of nerve connections between the brain and the hands is greater than between any other part of the body – the hands have 25 per cent and the arms 15 per cent of the total. The legs and feet we have less conscious control over – the further away from the brain, the less we’re able to fake.

A person’s hand activity will communicate a lot to us and hand movements of our own will influence how we’re being perceived by other people. It’s generally accepted that we can relay a message with greater clarity with accompanying hand movements.

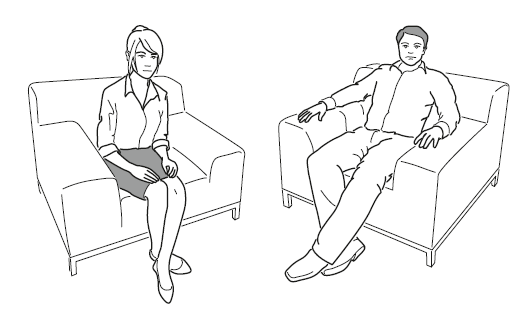

Status, hierarchy and dominance

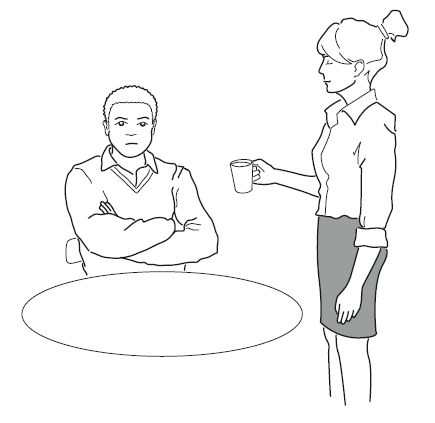

If you watch people interacting with each other you can often tell the ‘pecking order’ as to how a person perceives themselves in terms of ‘status’ or ‘hierarchy’ or if they consider themselves to be on an equal footing.’ Of course, it is observed more often in a working environment on an everyday level where you’ll notice how touch sends out a message both to the person on the receiving end and to observers. In business and in politics, tests confirm that, in the main, the person who perceives themselves to be of higher status is the one using the hands to initiate the touch. You’ll see it a lot in politics where the politician wants to let the audience (voters) know who’s in charge – and make sure they remember it – as well as the person who’s on the receiving end of the touch.

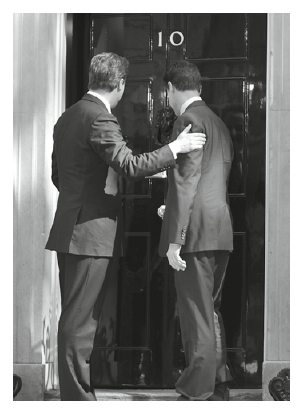

A wonderful example of this was demonstrated on the steps of 10 Downing Street in May 2010 when the two new coalition leaders met for a photocall to the world’s press after the general election.

Prime Minister David Cameron guides his new Deputy into Number 10

Cameron and Clegg: what is their body language really saying?

(James Borg, Daily Telegraph, 15 May 2010)

...The symmetries are all part of their supposed political chemistry. On first glance, David Cameron and Nick Clegg are alike in so many ways, in appearance, age, height and education – and in their gestures as well. But exactly how alike are they in reality? Throughout last week, their respective body language gave subtle, unspoken clues as to the real state of their relationship.

Prior to the press conference, the pair posed briefly on the doorstep of Downing Street – a ritual that Cameron would have almost certainly have rehearsed in his mind. He certainly had finessed that relaxed, authoritative air. In these situations, and faced with a barrage of cameras, the winner is the person who can seem natural in what is essentially an unnatural environment. After the introductory handshake, we saw both men pat each other on the back, a signal which neuropsychologists refer to as a ‘parental’ gesture. And what do most parents signify with this movement to their young? ‘I’m in charge.’ It’s a status reminder, and can be especially important in the ‘first among equals’ situation in which Cameron and Clegg now find themselves.

But their body language was more complex than that. Cameron patted Clegg first, who reciprocated with a pat of his own. Cameron then patted back, and Clegg did the same... before Cameron gave the assertive final pat with his right hand as he ushered his deputy through the door. This was both a classic repeat display of courtship, and a barely concealed power struggle. Crucially, by doling out the final pat, Cameron had the last word in the vernacular.

The press conference that followed was a chance to meet the ‘newlyweds’. Cameron came across as more assured, more prime ministerial in his manner and delivery, making frequent references to his new partner by gesticulating towards him with his right hand. When he gives a speech, Cameron has a subconscious habit of splaying his fingers, an open-hand gesture that projects trustworthiness. This in stark contrast to the closed, clunking fist deployed by the previous resident of Number 10.

Clegg, in between looking at his notes, attempted his now-signature delivery technique of looking straight ahead. However, with his general facial expressions more subdued than usual, he glanced down more than Cameron – a sure sign of nerves. After all, he had something to be nervous, and indeed embarrassed, about after being exposed earlier in the week as having been in talks on the sly with Labour – the romantic equivalent of an ‘ex-girlfriend’ – before finally deciding to go to the altar with the Conservatives.

When Clegg spoke, it was interesting to note that Cameron orientated his entire body towards him. When we are completely at ease and interested in another person, we turn not just our head but our whole body – and often the feet – towards them.

When Cameron spoke of the challenges facing his administration, Clegg turned only his head in his direction. He also displayed a number of microexpressions, fleeting subconscious gestures that last between three and five seconds, but which display discomfort. Clegg bit his lip on a number of occasions and touched the inside of his mouth with his tongue. This was noticeable especially when the subject of proportional representation was raised.

There was a change in Clegg’s later demeanour. As the prime minister spoke, Clegg orientated his whole body and feet towards him – a noticeable shift. As the prime minister answered questions, Clegg began to give nods and respectful glances. Rather than implying complete agreement, this usually suggests something more crucial to a working relationship – deference. Clegg is acknowledging that, although he is now a powerful player, Cameron is very much the man in charge.’

Some people use their hands in a natural way while they are speaking; others find it difficult and so it takes a certain amount of focus and awareness to get into the habit. It’s been noted that the more extrovert type of person will tend to use hand movements to accompany speech, as opposed to the more introvert type. You’ll often see that the most effective speakers are those who display a lot of hand gestures to reinforce a point – and their timing is in synchronicity with their speech.

So, apart from the face, our hands are the most expressive and communicative part of the body, and as well as adding to our speech we quite naturally use them in place of words. Small wonder then that we use them constantly to reinforce a point – and also why they are responsible for displaying a lot of ‘leakage’. So much so that we subconsciously pick up signals when we’re not aware of seeing somebody’s hands in a conversation, or even when we’re observing them speak (if their hands are behind a desk, rostrum or under a table, for example).

Experiments are continually being conducted in this area of hand display, and time and time again the results show that the perceived impression of somebody who is ‘hiding’ their hands is a negative one. Now, this is not to say that this is always the reality – that hands are deliberately being concealed from view. But impressions are formed by perception. In fact, everything we’re discussing in this world of body language is, as has been mentioned before, to do with perception.

How do you feel if your arms are hanging down by your side and you’re asked to give a talk? If you’re a person who uses your hands, however little, you’ll almost certainly feel uncomfortable because your mannequin-like pose will make for an unnatural delivery and the visual appearance would not inspire confidence. So, in body language terms (remember 55, 38, 7) the impact of your 7 per cent (words) would be completely overshadowed by the way that you said it (38 per cent), and also what we see – your uncomfortable demeanour (55 per cent).

Palms of the hands: up or down?

In the field of study relating to hand gestures we’ll look first at the position of our palms during our gestures. Much research has been done on the subject of palm position – to simplify, we basically have up or down. What’s the significance?

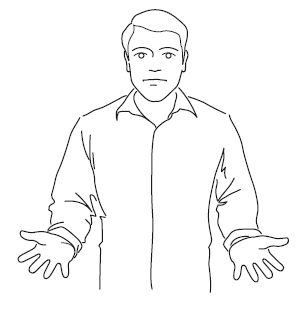

Almost exclusively the palms up position wins ‘hands down’ (excuse me!). The findings show that when you use the palms up position when you’re speaking, most of your listeners interpret the ‘message’ positively. Repeat this with palms down and the figure is much lower.

What’s the reasoning behind this? We associate the sign of an ‘open’ hand with friendliness, honesty and trust. We take oaths with the palm of the hand – ‘Can I be completely open with you?’ says one of the parties round a negotiating table, as he gesticulates with his open palm thrust forward. Since it’s usually a subconscious display, we tend to believe the gesture and it tends to put us in a more receptive mood to the other person’s message. It’s generally thought that people who are trying to fake a particular emotion or tell an untruth find it difficult to do so with their palms up.

Empty palms in ancient days equalled no weapon. That’s how handshakes developed (more on that later). The point is, it’s essentially a submissive gesture (think beggar on the street, or the villain’s response in a black and white Sherlock Holmes movie as Holmes, Watson and the Inspector break down the door in the last scene). So it’s a good indicator for you to judge the sincerity of a person when they’re delivering their message. They’re trying to convey to you that they are to be trusted (‘please listen to me with confidence’).

Now that’s all well and good, I hear you say, but what about the estate agents, used-car dealers, liars and other purveyors of this gesture? Don’t they know about this gesture and deliberately use it to hoodwink us? Of course they do. But by the end of Lesson 7 you’ll be able to filter out this gesture if you notice that it’s not ‘congruent’ (remember) with other ‘open’ gestures, and you experience lack of eye contact, an inappropriate posture, a false smile and a vocal give-away.

A gesture with the palms down is used to convey dominance or authority. You’re issuing a command here. An example of this was Hillary Clinton early on in her campaign for nomination in the presidential elections in 2008, as she tried to impress on the assembled throng that she was in control. Later in the campaign her advisers must have asked her to change to palms up. She switched to a palm (singular) up position. (Note: people find it easier to break the previous palms down habit if they switch to a single-hand palm up rather than try to do a palms up with both hands.)

So if our hands are so important when we’re dealing with others, even if it’s only subliminal on their part, then it means that in order to inspire trust and give out the right impression they need to be visible. However, we have to be careful because our hands are able to send cues to an observant listener who, as well as picking up positive vibes, may pick up negativity or anxiety.

You can just imagine, for example at work, a colleague of equal status to you gesticulating with a closed palm position, in an up and down fashion, and saying: ‘Can you just move that pile of directories that somebody’s just dumped there – they’re in the way?’ With that gesture, it sounds and looks like a command. It’s not your boss that’s asking you, it’s someone of equal status. Result – could lead to antagonism. It’s not the words, it’s the gesture and the way that it’s said. Double whammy!

Now suppose that same request (even with the same words) is made with an open palm upwards gesture. It then becomes more of a submissive request (or favour) or a sign of helplessness and is less likely to upset the other person. You are far more likely to carry out the request.

There’s a variant of the palm down gesture which has all the fingers closed together and it’s instantly recognisable as the adopted salute during the tenure of the Third Reich, seen many times on the grainy newsreels showing Adolf Hitler.

What’s the point?

I’ll just mention, while we’re talking about the effectiveness of palms, an irritating gesture that occurs when you point your index figure at someone. You have the closed palm position, which turns it into a fist, with a finger point. How do you react to a finger point? Doesn’t make you feel good, I’m sure. Evokes memories of childhood perhaps? Characteristic of a parent, teacher or other irritating person that we’ve come across in later life? It’s an aggressive gesture and it’s surprising how many people are unaware either that they do it or of the effect it has on the receiver. Almost throughout the world, it’s associated with the same sentiment (I think you get the point).

If you are the proud owner of this gesture, attempt to get rid of it because it causes offence. It’s okay for television perhaps – ‘Natasha – you’re fired’ (The Apprentice) – but in real life it causes antagonism.

Displacement activities

Time for an important term in the psychological world of body language – displacement activities. These are things you do to help displace anxiety (or nervous energy, to put it another way). Please remember this term. It will help to serve as a memory-jog in helping you to label it and to read it in other people. These little actions can be fleeting, but very revealing.

Displacement activities are movements performed by us when we’re experiencing any kind of inner conflict, torment or frustration. The essential point is that these are just small movements that may tell us an awful lot about what may be going on inside a person’s head. As with most things in life, it’s usually the small things that make a big difference. What small gestures do you make that ‘leak’ out your true feelings (usually without you even knowing)?

BODY WISE

If you underestimate the capacity of small things to make a big difference, then a quick question: Have you never been to bed with a mosquito?

Trains and planes

When an observation survey was conducted at railway stations and airports, where tension is often high, some interesting activities were noticed. Firstly, there were activities that were very clear in denoting tension. Secondly, there was a type of disguised activity because passengers obviously did not want to reveal, in any way, that they might actually be apprehensive – or frightened – of boarding a plane and that they would rather flee the terminal building.

Typically the ‘displacement’ behaviour involved constant rechecking of tickets and passports, making sure the wallet was still in the inside pocket (the reassuring tap), picking up and putting down luggage, gazing at a mobile phone repeatedly. All of these things had been checked, invariably only minutes before.

Interestingly, and to be expected, there was 10 times as much evidence of displacement activities at airports as at railway stations (just 8 per cent of passengers boarding a train revealed evidence of these activities, while the figure was 80 per cent at the check-in desk at airports). In addition, it was observed that there was a lot of head scratching, facial contortions, tugging of earlobes and general fidgeting and fumbling in the airports.

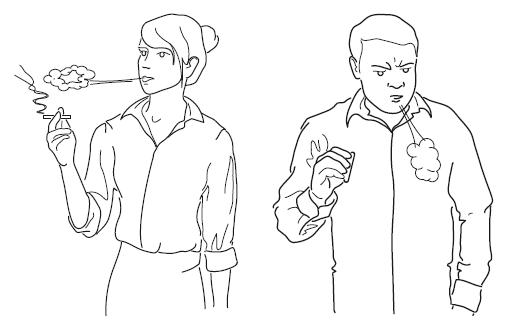

There was also evidence of stress-smokers sitting quietly and making a big show of the whole smoking ‘ritual’ – locating the packet, finding the lighter or matches, lighting and putting out the flame, strategic placing of the ashtray, flicking of nonexistent ash from the clothes and then finally the stubbing out of a barely smoked cigarette with an exaggerated action. (The extensive smoking ban means you’ll now be unable to enjoy your role as a ‘voyeur’ and witness this elaborate display of inner conflict. However, you’ll see a similar performance in other situations, no doubt.)

I’m sure this is going to make you all the more aware of your own behaviour the next time you’re waiting to board a plane. Also it will raise awareness of your own display of displacement activity in many situations, and once you’ve identified them you can aim to rid yourself of these telltale activities if you’re in a situation in which you don’t want to come across in a particular way.

We all have our own personal displacement habits that come into play to rescue us when we’re experiencing a period of conflict or tension – chewing gum, nail biting, eating, drinking, keeping a cigarette in the mouth (even if unlit). Movie star Clint Eastwood had an interesting displacement gesture in the so-called Spaghetti Western films he made. He would have the unlit cigarette in the corner of his mouth at all times, but instead of removing it from his mouth whenever he had to speak to someone (in what was usually a tense situation), he would light it and then start talking, with it still in his mouth.

The hands, because of their close association with the brain, are particularly prone to self-directed activities when we’re experiencing conflicting emotions. These displacement gestures provide comfort and dissipate energy at the same time. They tend to fall into two areas – the first is externally directed; the second is internally directed (self-comfort gestures) – this is covered later.

Displacement that is externally directed includes fiddling with clothing or objects such as keys, pens, spectacles, coins, the stem of a wine glass, a mobile phone or rings on a finger. The point is that it may be a reflection of our feelings, but it’s irritating for the onlooker. Look at the ‘context’ and see if you can identify ‘clusters’. Then take action.

Smoking styles

Smoking (as discussed earlier) is another external displacement activity worth elaborating on because it gives us some additional clues. When feeling anxious or nervous it gives the hands something to do. Much research has been done into styles of smoking and what these display about a person’s state of mind at the time – positive or negative.

What do we know? Well, barring situational factors – like proximity to other people and being in a confined space – that determine where a person is able to exhale, research suggests that:

- people in a positive and perhaps confident frame of mind will predominantly exhale in an upward direction

- blowing in a downward fashion tends to be associated with negativity, anger or frustration.

In addition, the speed at which the exhaling takes place gives an idea as to the intensity of the emotion. So the faster the upward motion, the more heightened the feelings of confidence or positivity towards something. Conversely, the faster the downward motion, the stronger the adverse feelings.

Other idiosyncratic smoking gestures include extinguishing a cigarette. You’ve seen it a thousand times in movies, restaurants, meetings and during negotiations. (All of this pre smoking ban of course!) The way that a person puts out a cigarette reveals a lot.

- The fast, intense drilling of the stub into the ashtray – mind made up (ready for action).

- The slow, careful, exaggerated gesture, by contrast – not quite sure (something is troubling me).

Likewise, a person who inhales very deeply, in a slow and deliberate way, is usually in a pressurised state and the cigarette is more of a ‘need’ than a displacement. You’ll see smokers absent-mindedly tapping on the side of the ashtray, at a frequent rate (even though there’s no ash on the cigarette). Similarly, they’ll flick the bottom of the cigarette with an upward movement of the thumb to remove non-existent ash. This person’s in an agitated state (whatever did you say to her?).

A word on cigars. Because of their size (and I’m talking about large cigars) you find different smoking gestures as well as different types of people compared to your average cigarette smoker (think Winston Churchill and boardroom bosses). Big generalisation here – because of the connotation of success that attaches itself to those people who wield cigars (rather like champagne), you’ll find that many of these smokers (almost exclusively male) tend to use them as more of a ‘prop’.

Cigars, unlike cigarettes, tend to go out if you don’t take frequent puffs. So you’re able to legitimately hold on to a cigar for a long time; a perfect displacement activity for the hand and a handy psychological crutch. As comedian George Burns famously said (he was 96 at the time) when asked about the cigar which he never lit but which just stayed in his hand the entire time during his stage and TV shows: ‘At my age, if I don’t hold on to something, I fall over!’

Self-comfort gestures

These are displacement activities that are internally directed.

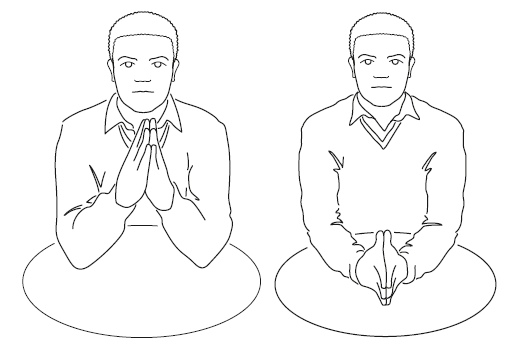

Hand clasp

You’ll observe people clasping their left and right hand together in what Desmond Morris called ‘holding hands with himself’ while talking. While it may seem like an innocuous gesture, just like everything to do with the hands it’s usually telling us something, and it’s not connected with confidence as it may appear. The person is in a state of conflict. The linked hands may move as the person speaks in a kind of rhythm – but all the time they remain locked because of the state of tension the person is in. The person is suppressing a negative attitude that they cannot display.

There are two main positions if a person is seated at a table or desk. The elbows may be on the table with the clenched hands in front of the face, or the hands rest on the surface of the table or desk. (Sometimes the hands may be a little lower and actually rest on the lap.)

The interesting thing about these positions is that research shows that the higher the position (i.e. in front of the face) the more negative tension exists. This person would be resistant to you and your ideas. If the hands are against or near the mouth area the person is holding back on a potential ‘torrent’. The person with the hands in the lower position would not be so agitated. They may be irritated at something, but they’re not at a potential explosion point like the other person.

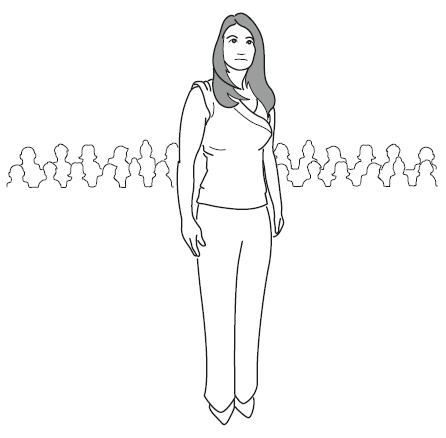

Sometimes you’ll observe a person who’s standing adopt the hand clasp with the hands positioned in front of the thigh or crotch area. This is usually quite different from the situations we’ve just illustrated. It’s nothing to do with negativity or confidence – more likely nervousness. Many people adopt this ‘crotch covering’ stance because they don’t know what to do with their hands, and it’s also a vulnerable position when you’re standing front on so this offers a protection barrier.

‘Steepling’ of hands

It’s a good time to talk about a hand gesture that seems to fascinate those of us who spend time studying non-verbal behaviour. It was first brought to attention by the anthropologist Ray Birdwhistell. He noticed that the type of person who didn’t engage in animated body language during interactions – in fact their gestures were, apart from facial, almost non-existent – used the ‘steeple’. What’s that? It’s a hand gesture that occurs in isolation of other gestures, so no ‘clusters’ here. In fact it displays confidence.

It looks very much like the pointed top of a church steeple and you may have seen it used by ‘authority’ figures when they’re being interviewed by the media, or when they’re interacting with other people (usually ‘subordinate’). Apart from politicians, it’s common to see professional people – hospital consultants, lawyers and the like – engaging in this action.

The gesture tends to come in two guises. When seated, if a person is speaking they tend to adopt the raised steeple. The elbows rest on the table, the two palms come together and the fingertips of each hand will gently touch each other and remain in that position – like hands that are praying. If a person is listening they may have the lowered steeple which can be resting on a surface or on or between their knees. It’s usually a more cooperative gesture in this lowered position and the research also shows that women tend to adopt this lower steeple (in a listening role) rather than the raised one.

More men than women adopt this gesture and sometimes if, instead of an ‘open’ body language stance, the person tilts their head and body back they can come across as arrogant. Sometimes you’ll even see people steeple above their heads. All the studies show that when people observe steepling in others, they perceive it as a self-assured gesture. Evidence also shows that people who switch from a clasped-hands defensive gesture to a deliberate steepling gesture experience completely different feelings.

TRY IT

Adopt the hand steeple in a conversation or meeting. See how it feels. Does it alter your emotional state? Does it make you feel more knowledgeable/confident? If you’re feeling nervous and worried about your hands shaking in front of another person, try the steeple. It should steady you.

If you’re a little bit nervous – say for an interview or an important meeting of some sort – the steeple prevents the slight tremor of shaking hands that is sometimes visible during these encounters. The more you do it, the more it becomes a habit, until it becomes natural.

If you find that you’re unconsciously wringing your hands all the time, be wary of this and switch ‘midstream’ into the steeple position. Watch how your concentration improves as you find that instead of thinking about yourself, you’re thinking about the other person.

There’s another hand gesture that, unlike steepling, involves interlaced fingers. Normally interlaced figures are more associated with nervousness or defensiveness. When it’s combined with a ‘thumbs up’ type of gesture, this hybrid display is a confident one. It’s a positive gesture and to the onlookers it inspires confidence in the speaker.

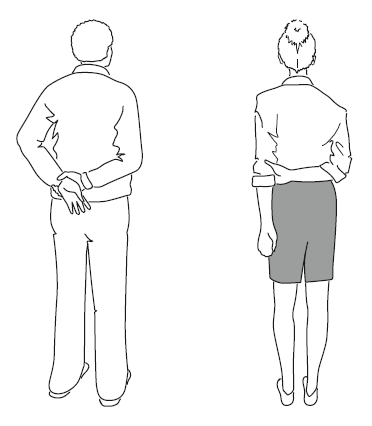

Hands behind the back

You can no doubt recall someone from your past, or someone you currently deal with, who puts their hands behind their back and grips them together. It’s not a hiding of the hands gesture – on the contrary it projects confidence because you’re happy to expose the vulnerable front of your body. We’ve all seen policemen, higher ranking military, hospital surgeons and university lecturers adopt this stance.

It’s been shown that adopting this stance can actually give you more confidence and change your feelings and the impression that people have of you. I remember many years ago showing three visitors around some advertising agency offices. At the end of the tour I instinctively handed over some annual reports to the person who had been walking around with his hands behind his back. It turned out he was an IT trainee (he’d been there six weeks) and the other two were the managing director and financial director.

Arms

There’s a wealth of difference in what a few inches can convey about an attitude. If the second hand behind the back is not gripping the other hand but the wrist, we’re talking about a situation in which the person is annoyed or frustrated at something. (It can also signify nervousness.) The hand is almost controlling the wrist to prevent it being unleashed. The further up the arm the hand grips, the more anger or frustration the person is experiencing.

Hand to face/head

When under stress or discomfort of any sort, we’ll frequently engage in self-comfort gestures that involve the hands touching the face, the head or the hair. (Does this ring a bell with your own behaviour?) The interesting thing about these behaviours is that we tend to touch the areas that may have been used to comfort us as children. So the school of thought is that we’re comforting ourselves in the way that we were consoled in our childhood.

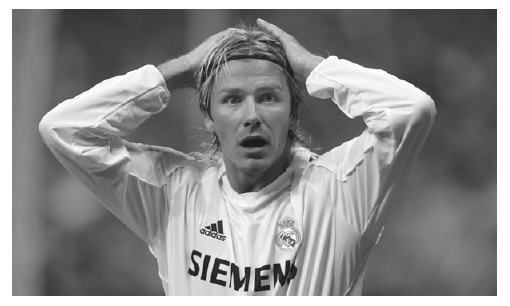

For example, if we’re undergoing any kind of anxiety we might brush our hair with the hand (top of the head or back of the neck area for men, typically). Does that sound familiar to you? Ever watched a ‘celebrity’ on a chat show after they’ve just sat down and the applause of the studio audience has subsided? Up goes the hand to smooth the hair on the top or back of the head (usually male). Or the person returning back to their parking space and seeing in the distance the sight of a traffic warden printing out a ‘ticket’? Up goes the hand...

David Beckham

Another variation of this – and quite often you’ll see it with both hands – is the sight of David Beckham or some other footballer as they miss the goal in a penalty shoot-out, or a tennis player as he or she double faults on match point at Wimbledon. The player’s hands will instinctively go to the head or back of the neck in a self-comforting gesture. The point is, it betrays some kind of displeasure, anxiety or momentary nervousness. Quite evident what it means in this case – millions of ‘gutted’ fans would probably be able to interpret this element of body language without any trouble. This ‘cradle’ gesture with both hands can be seen in any situation in which we respond to bad news or anxiety and need protection. Memories of parents supporting the head as a baby provide the self-comfort, which – for that fleeting moment at least – provides us with security.

Our skin has receptor cells which respond instantly – because of their sensitivity – to touch. They send messages to the brain and provide us with comfort. Never underestimate the power of touch (a little more about that in Lesson 5). So we frequently resort to self-comfort actions that almost recreate (sorry, taking you back to childhood again) how our parents and other adults made us feel secure when we were babies or toddlers.

Interpreting hand-to-face or hand-to-head gestures requires a little work, initially by becoming aware of how people typically exhibit these and at what point in a conversation they may frequently occur. This provides us with clues. Of course you’ve built up a reservoir of knowledge over the years, which you instinctively tap into. But, as with all the other analysis that you’ll be doing on a day-to-day basis to become proficient, you need to pay attention and become super-observant.

Boredom

Quite often you’ll notice the hand-to-face gesture that gives a clue that the person listening to you is, for whatever reason (that’s for you to deduce!), not exactly riveted to your words of wisdom. (Equally you may display this when you’re on the receiving end.) This may occur during a work presentation, with friends in a coffee bar, at a party or gathering, during a training session – it happens everywhere.

The typical hand-to-face gesture is one where the hand supports the entire jaw with the elbow resting on the table. Generally, the more you see of the hand covering the jaw (the entire cheek), the more bored or disinterested the person is. So if the whole hand covers the entire jaw right up to the eyebrow – sounds like serious boredom. When we become disinterested or bored with another person it gradually builds up momentum, to that final hand position which is holding up the head.

CAUTION

Sometimes, depending on the positioning of the hand on the jaw, it may just be a switch to a position that intensifies concentration by the listener, either because it’s something that concerns them or because they want to display empathy to the listener (‘Oh that’s awful. He really said that to you? ...’). In other words – the opposite of boredom. (See why body language is so confusing?)

If a person was showing attentive signals prior to that and then suddenly switches to this extreme position, it’s unlikely to be a boredom gesture. As we said earlier, boredom or disinterest usually builds up momentum and doesn’t switch that easily.

Sometimes you’ll see the hand folded in a fist arrangement with the fist gently holding the lower part of the cheek. It may be a boredom signal but sometimes a person switches to that position when hearing something disturbing, or something that ‘touches a nerve’. Later, the hand may be removed from the face back to its previous resting position. It’s the eyes that will confirm what’s being felt – the cluster, remember?

However, the fist supporting the chin is a different matter – just as with the entire open hand covering the whole of the cheek or jaw, they’re both propping up the head. So, it’s a danger signal if you’re giving a work presentation, training session or speech and you see a multitude of heads being supported in this way.

If they’re accompanied by doodling on pads, daydreaming (look at the eyes!), blank expressions, a fake smile, the occasional sigh, tension in the jaw (we’re now getting some cluster activity) and increasing movement of limbs – do something!

To check for the boredom signal you need to look at the eyes in conjunction with this hand-to-face gesture. If the eyes are looking down, or half shut, or there’s a bleary-eyed look (that almost says ‘please stop the fight’), then you can almost be sure that you need to change tack to try to re-engage, or decide that the situation is hopeless and abandon your cause.

Disapproval or disagreement?

Sometimes you’ll see a person perform a mouth cover, whereby the fingers of the hand cover the mouth with the thumb pressing against the cheek. Usually it indicates that the person disagrees with what the speaker has said or doesn’t believe they are telling the truth. The hand subconsciously goes to the mouth area. The interpretation of this gesture? It’s as though the brain is directing us to block ourselves from blurting out the fact that we disagree, disapprove or distrust what the person is saying. Take heed if you see this action in an audience of yours – be it displayed by one or many listeners. Again, as we’ve said many times before, change tack. Try to get to the root of the problem and look for other clues.

When ‘the boot is on the other foot’, and the person who is speaking performs this gesture immediately after saying something, it may indicate that they’re lying about something. Consequently, the neurological instruction (from the brain) is to try almost to prevent more untruths from coming out of the mouth (we’ll look at this in Lesson 6).

A variant of this is when you see somebody put their fingers in their mouth. This usually denotes that the person is experiencing discomfort or pressure of some kind. Any kind of anxious situation makes us want to put something in the mouth. Just being put on the spot to make some kind of everyday decision can produce this action. I’ve seen people staring at railway timetables adopting this pose as they anxiously work out connecting train services. This comfort gesture takes us back to childhood, it is said, when as young children we looked to the mouth to placate us, from feeding to thumb-sucking.

So, if you find yourself doing this when you’re not even conversing with anybody, and may even be on your own, check your own feelings. The whole point about body language is that it not only tells other people how we might be feeling but also provides us with a reminder of our own internal dialogue – which has created the feeling. We know that if we change the thought then we change the feeling – which changes the non-verbal behaviour.

So if you’re with somebody be aware that this gesture may tell them something about your state, which may not be what you want to broadcast. Equally if you see this happening with the other person you have an opportunity to delve into the circumstances and to see if it is anything related to you. If it’s not, you at least have had the chance to show some empathy through your questioning.

BODY WISE

The way you feel affects the way your audience feels.

Another common hand-to-face gesture is one where the thumb supports the chin and the all-important index finger points in a vertical direction up the side of your cheek. It’s not generally a gesture that denotes positive feelings but rather disagreement of some sort. There’s often confusion with this pose because it is similar to one denoting evaluation (rather than negativity), but it’s the positioning of the thumb that provides us with the clue. You’ll often find that the person holding this position will occasionally move the index finger a fraction, to touch the eye (maybe a rubbing motion), blocking you out even more!

We’ll often see the eye rub in isolation to any cheek or chin touching. Sometimes it involves pulling down an eyelid.

The most common actions

It was noted in a survey of hand-to-head/face actions in stressed situations that the most common were (in decreasing order):

- jaw support

- chin support

- hair touching

- cheek support

- mouth touch

- temple support.

The study showed that these actions were common in both males and females. Temple support was more common in men by a 2:1 ratio; with hair touching there was a 3:1 bias in favour of women.

BODY WISE

Our self-comfort gestures of stroking, hugging and touching, when experiencing discomfort, are said to relate to childhood because they are the subconscious gestures of another person’s consoling touch.

When someone switches to positive ‘evaluation’, we’re entering into more favourable territory. There’s more of the chin and less of the rest of the face that our hands gravitate to. A person who may be interested in your message often adopts a lightly closed fist resting on the cheek with the index finger pointing upwards, usually by the ear.

The next stage, when you ask for interaction or for a person to make a decision about something, is usually a switch of the hand to the chin. If it remains there, or perhaps they lean forward and remove the hand from the face altogether, they’re still interested in your presentation, speech, proposal, training session, holiday snaps, recipe for blueberry muffins, pontification on falling house prices or the rising price of fuel. If they switch to a cluster of boredom signals – there’s more work to do.

Arms

You remember we spoke about open body language and closed body language? By now I’m sure you’ve taken in (something that you instinctively knew) the fact that it’s only when we’re in an ‘open’ position that things run smoothly. Well, it’s no different with arms. We’ll be talking about arm positions and what they signify, and of course what effect it has on your own brain when your arms are fixed in a certain position.

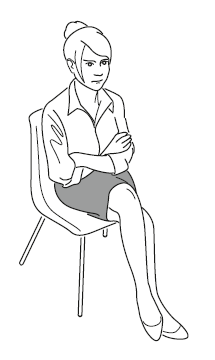

Folded

Arms are particularly interesting in body language terms because in a folded position they have the capacity to form a protective ‘barrier’ between people and close down communication. Have you seen ‘bouncers’ standing outside Fifi’s nightclub at 1 a.m. – can you remember what their arms were doing? What about inside the nightclub (you managed to get in?)? What were the girls doing to show you that they weren’t interested?

Since we seem to have to revert back to childhood to find the answers to much of our adult body language action, think back to how you used to hide behind things for protection as a child. If it wasn’t a parent, it might have been a tree or table or anything that provided a defence between you and the outside world.

As we grew up we discovered we had our own portable defence mechanism – our arms. They could be crossed – in a number of ways – in times of discomfort. We adopt defensive postures when we hear something we disagree with, if we’re in a tense situation or if a negative thought passes through our mind creating a corresponding feeling.

BODY WISE

Crossed arms (aside from temperature reasons) nearly always signifies some form of discomfort.

The crossing of arms is a gesture that you see throughout the world. As mentioned earlier, it is essentially signifying discomfort on your part, and as such is transmitting that to observers. We’re always worried about what our body language signals are conveying to other people, right?

Of course, before we start jumping to conclusions about people we should note that there are some people who have a habit of crossing their arms – in a loose manner – as a ‘self-hug’ comfort gesture. It almost becomes their ‘default’ position to show they’re relaxed and ready to hear your conversation.

A good example of this is the character Rachel (Jennifer Aniston) in Friends. She folds her arms to get comfortable to listen to the latest tales of woe from Monica, Joey, Ross, Phoebe or Chandler.

Jennifer Aniston in her typical, relaxed pose

Whenever we humans experience anxiety or distress we tend to withdraw our arms. The arms will always go straight to the sides or will close across the chest. This provides us with a defence barrier and – just as important – self-comfort. Since we’re always concerned not only with what signals we’re picking up but also with what we are giving out, we should be careful when adopting any crossed-arm position – even if the central heating needs turning up!

BODY WISE

Studies confirm that people witnessing crossed arms in another person will interpret it as a defensive or negative gesture.

There are a few crossed-arm positions that you no doubt come across in personal and working life. The common one, which is probably the one you recognise in yourself from the time when your genetic ‘hard-wiring’ first introduced it to you, is the general crossed arms. Both your arms are folded across your chest (one or both hands may be tucked under between the arm and chest). This is the most common arm cross. It’s seen throughout the world and usually silently screams out the same thing (oh so politely): ‘I’m feeling defensive or negative about someone or something.’ As well as in your interactions with other people, you may see this gesture as you go about your daily life: on tube trains, in lifts, long post office queues, waiting rooms, at social functions. Anywhere that people are experiencing discomfort or insecurity.

At work, during a meeting or a discussion that you’re having with a colleague, client or boss, for example, if it suddenly occurs (when ‘baseline’ behaviour tells you it’s not normal) then you may have come up with something that they don’t agree with. They may be verbally indicating that everything’s okay (this time with a hesitant and softer voice), but this gesture, perhaps accompanied by a change of facial expression (less ‘open’), should set alarm bells off.

Consider the following scenario:

Simon (in departmental meeting) talking to his PA: ‘Okay, let’s firm up on that murder mystery weekend in Brighton. I’ll fix that four-star hotel, the one on the seafront. You know – the one with that atrium – it’s got that health and leisure club in the basement? Bring your boyfriend – my wife’s coming. We’d like to meet him. (Karen’s hand covers her mouth.) What’s it called ...?’

Karen: ‘Yes, Thistle Brighton. It is a lovely hotel, very atmospheric.’ (Her voice pitch and tempo is different and her words tail off as her hand moves down to clasp her neck.)

Simon: ‘That’s it. Great view of the sea from the restaurant. Handy location for the shopping too.

(Karen’s now looking downwards and has also crossed her arms.)

Well, Simon didn’t pick up the signals. All the obvious clues were there – there was definitely something wrong. He should have known that her ‘baseline’ behaviour included good eye contact at all times. That should have been the give-away that something was wrong. Then there was her speech – hesitant; she covered her mouth, clasped her neck and went into an arm-fold. A ‘cluster’ of anxious behaviour. It turned out that she had just split with her boyfriend that weekend.

So there was a ‘cluster’ informing us that the genuine message was leaking out from the non-verbal actions. Since we know that the true meaning (because it’s hard to fake) of any message is from the body, what we observe from the body and vocal signals (the 55 per cent and 38 per cent) tells us that we’re not going to get anywhere with this person unless we try to find out what’s wrong.

Certainly, as long as the person remains with this defensive arm-fold barrier their attitude is not going to change. ‘Something’s gotta give’, as the saying goes.

When I’m confronted with this situation, I usually try to get the person to do or look at something. If you hand them something to look at or get them to do something, it makes them break the ‘deadlock’ of their arms.

I remember when I was giving a presentation at work with a female colleague and she sensed that the client had suddenly turned into ‘not interested anymore’ mode. There was no legitimate or relevant document or brochure to hand him. She picked up the new jar of coffee and pretended it was too tight for her to open and asked the ‘now beaming’ client if he would oblige. Arms unfolded now, a premature coffee break and also an informal interlude to ask if there were ‘any points that needed clarifying’. (Never underestimate the power of a damsel in distress!)

Types of arm-cross

The important thing about the arms-folded gesture is that the demeanour and mental attitude of the person is fixed in that mode as long as they continue with that posture.

Arms gripped

Another type of arm-cross that occurs is where the arms are gripped. The hands grip both of the upper arms in a tight fashion as if to ensure that they keep the arms down, so that they won’t get away. It’s like the tight gripping of the arms of a chair. The person may be experiencing extreme anxiety or anticipating an unpleasant event, or feeling extremely stubborn about something. You see this pose during union pay negotiations with the dissatisfied members listening to speeches by opposing bodies. If you’re displaying this in front of other people, you can imagine the image you’re conveying.

Crossed arms (with fists)

At other times you may see a crossed-arm position with fists. Doesn’t sound good, does it? The fists are placed under the arms. Not only have we got defensiveness here, there’s potential hostility on the menu too. Facial expressions may confirm these feelings, as well as perhaps foot or leg movements. Make sure you don’t ‘mirror’ this pose if you’re trying to achieve a conciliatory outcome. Use your open body language to encourage this person to open up and disclose the reason for their feelings. You know what the feelings are – you want to know why. You may see nightclub bouncers, security personnel and policemen adopting this pose. It gives out the signal they deliberately want to give out.

Crossed arms (with thumbs up)

There’s another arm-cross that body language researchers have come across more and more. It involves the thumbs in an upward position. I’ve seen it a lot with tradesmen when they’re negotiating or justifying their prices to householders faced with some emergency repair, or with car mechanics in the same scenario.

The crossed-arms stance conveys discomfort or apprehension, but the thumbs up conveys a certain amount of confidence.

There’s something about the thumb – what is it? We know, for example, that confident people often have a thumb (or two) sticking out of a jacket pocket. The late John F. Kennedy – looking at all the old newsreels – always seemed to have his hands in his jacket pockets with the thumbs sticking out.

Yes, the builder and car mechanic we spoke of earlier feel uneasy about the process of maximising the amount of cash they would like to extract from you. But at the same time they feel confident because they know you’re faced with a particular situation: you’re in a fix (and they know a man who can get you out of it!).

So you’ll often see this type of arm-cross both in and out of work, and where it is in evidence in a working environment you know that your colleague or the person you’re in charge of, while experiencing unease at the time, also feels reassured about their position.

The partial arm-cross

Before we leave this important topic we’ll take a look at the way we may try to minimise the display of this defensive gesture. You probably do this yourself from time to time. You’ll engage in a partial arm-cross – with just the one arm. Just the one arm will form a defensive barrier by reaching across to grip the other arm. It’s quite common with women and you’ll see it a lot when groups of people are conversing, especially if they don’t know each other well.

Back to childhood for a moment – it reminds us of when we were held by the arm or hand when we were afraid. You’ll see this single arm-cross as candidates are listening to results on the stage on election night in their constituencies. Also, it’s very evident when people are waiting to receive an award or prize for some sort of contest.

Sometimes, this partial arm-cross shows a variation. On occasions we’re not in a position to grip the other arm. We don’t have the opportunity for self-comfort so we have to resort to disguise. We don’t want people to know how we’re feeling. But we’ve still got to displace nervous energy and we still need the comfort of a barrier, however fleeting.

It won’t surprise you to know that people in the public eye, like politicians and ‘celebrities’, need to keep up an image and therefore engage in disguised defensive gestures all the time. We’re privileged to put the microscope on them usually through the TV camera. So they have to work extra hard to ‘look the part’ even though inwardly they are experiencing great discomfort.

Glossy magazines are always picturing couples arriving and leaving functions and nightclubs. Who’s she with? Who’s leaving with him? How is she holding him – looking at him? What’s the body language telling us? The slightest nuance of any revealing body language will be taken down, Ms (Kate) Moss, and used in evidence against you.

So celebrities and people in the public eye (who have an image to project – and protect) may typically have an arm crossing over their body if they’re walking on a red carpet, or entering Downing Street, or walking up the steps of a fashionable restaurant in LA. An arm may cross over the body to straighten a watchstrap (sometimes there is no watchstrap); another person may straighten an already straight tie. An arm will cross over J.K. Rowling’s body while walking on the red carpet and her hand will rise to her ear to straighten an ear-ring. All of these things are handy defence mechanisms in the absence of a permanent barrier.

BODY WISE

You are what you project. Actors, politicians and other ‘celebrities’ are trained to be acutely aware of self-presentation. The manner in which we project ourselves is an indicator of our mood as well as the level of comfort or discomfort we are feeling.

When it comes to our arms, if we’re in a relaxed state, the arms are by our side. It conveys an impression of openness and confidence (even if you’re not feeling that way).

HRH (or hands revealing hesitancy!)

In England, the Royal Family are often cited when we’re talking about disguised gestures, purely because of the sheer number of engagements that they have to attend – the opening of this, the opening of that – and so we constantly witness the obvious discomfort that they still feel, even after years of practice.

HRH The Queen is noted for the handbag that is constantly over her arm in front of her body, giving her a barrier at all times when she needs it. Prince Charles never disappoints – he has some ‘endearing’ gestures, especially the ‘signature’ one that he uses to reduce anxiety. Typically, as he leaves the royal car and walks past the crowds towards, say, the Royal Albert Hall, his arm will cross over to tamper with his cuff-link. Sometimes, he’ll treat his audience to a second ‘signature’ displacement activity. Even though Royals are known for not carrying money, he’ll cross his arm over and pat his jacket around the inside pocket area to make sure his (non-existent) wallet is still there. A wallet no doubt containing money that he would need for purchasing an ice cream during the interval and an ‘Oyster’ card for getting back home to the Palace after the show.

Hand to neck

The hand instinctively goes to the neck in many instances when we’re undergoing anxiety. Women tend to touch the neck more often than men. As a self-comfort gesture we’ll stroke the front or – commonly with men – massage the back of the neck. Men will typically enfold the area right under the chin with their hand, stimulating nerve endings.

It’s noticeable that women experiencing anxiety of some sort will stroke the front of the neck at times, or if they’re wearing a locket or necklace will fiddle around with this. When emotions are running higher it’s interesting that women touch or completely cover the neck ‘dimple’ area just above the breastbone. They may cover the area with their hand the whole time until the feeling of ‘distress’ has passed.

I noticed an interesting display recently in a hotel lounge with a widescreen TV. A number of guests – men and women – were watching one of the later episodes of Masterchef on the BBC. The tension was high as the nervous contestants stood there waiting for the results to see who would be leaving the show that week – their autonomic nervous system displaying their heavy breathing. I noticed four of the seven women seated around the TV bring a hand up to the neck to clamp it. The hands stayed there the whole time until the result was announced.

So, when you’re observing body language cues from women take a look to see if the hand goes to the neck and what the position is. From handling a necklace, to stroking, to a full clamp – this should give you an idea as to the intensity of any discomfort. Again, look for the clusters in order to make a more-informed judgement.

Hand to eyes

We looked at eye ‘cut-offs’ in an earlier Lesson. We’ll bring the hand as a shield over the eyes when we’re faced with seeing something unpleasant, or someone has said something to us that provokes an instant feeling of stress and anxiety. The hand is shielding us from ‘seeing’ the reality of life – even if we’re about to hear something unpalatable.

Ex-PM Gordon Brown’s discomfort is relayed around the world

An illuminating – and painful – example of this was provided to viewers during the 2010 election campaign in the so-called Duffygate scandal. The campaigning prime minister Gordon Brown was in the BBC studios on the Jeremy Vine Show when the host told him that reporters had picked up some of his private comments in his car, after he’d spoken to a constituent – because he’d left his microphone on. The PM began to apologise for what he’d said because they were private comments, but then he was told, to his surprise, that a recording of it was just about to be put on air. Gordon Brown’s eyes closed, his hand went to shield his eyes and his head slumped down almost to the table. The recording was then played. This shot in the studios was shown to TV viewers around the world.

It’s a measure of the impact of this interview – and the visual images – that it won the ‘Interview of the Year’ award in the prestigious Sony Radio Awards held in London in May 2011.

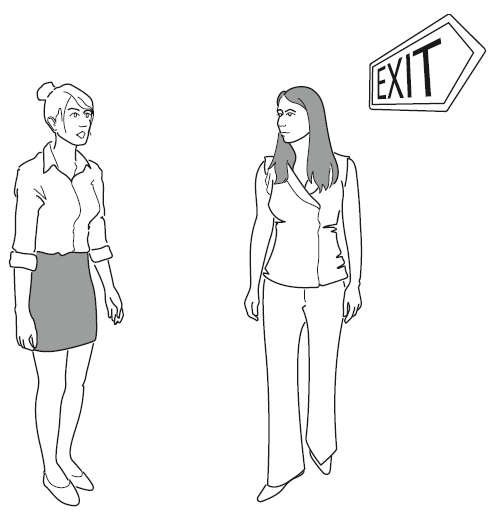

Feet

Like the arms, we can pick up a lot of information from leg gestures, especially when they are accompanied by arm signals to form an all-important cluster. Feet are important too – we’re conditioned to turn towards things and people who we like. Turning the feet away shows that we want to distance ourselves from a situation. Usually, we’re unaware of which way our feet are facing – until we actually look down.

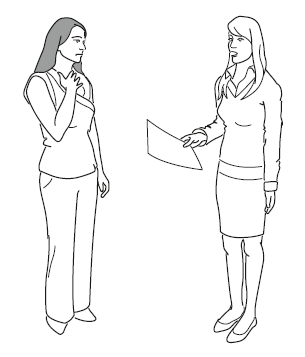

As you’ll see in Lesson 5, it’s this lower half of the body that is most revealing in the detection of lies. What we call intention movements are very revealing in terms of legs and feet. For example, if you’re conversing with someone facing you, and she later on in the conversation turns one of her feet in an outward direction – the other one still facing you – even though you’re getting on fine, it’s a signal she needs to or wants to go. Her body is still facing you front on, but one foot is pointing elsewhere (towards the exit point). She may have another appointment to keep or has decided that she just wants to go. The feet provide a great deal of information about a person’s attitude.

Picking up an intention cue quite often saves a relationship because some people, out of politeness, don’t want to verbalise what their intentions are. They rely on the body language skills of the other person – that means you. If they have to keep making repeated intention movements, it can irritate. Often it’s the last thing they remember about the interaction and so it can cause negative feelings.

Sometimes there’s no confusion. You’re talking to someone – they’re standing to the side of you with both feet pointing away from you. Despite the pleasant facial expression, it’s obvious from their feet as to where they’re heading.

The reason why the feet are regarded as being one of the most ‘honest’ parts of the body is, according to some researchers, that since the beginning of time the feet and legs have had to react to threat and danger without conscious thought.

Our lower limbs give out information about negative and positive thoughts. You may bounce your feet up and down with excitement while you’re sitting in the concert hall waiting for Madonna to arrive on stage. Equally your crossed leg may be kicking a foot up and down impatiently in a reception area because the interviewer is running 30 minutes late for your job interview.

Towards or away?

As we briefly touched on earlier, it’s in the nature of human beings to turn towards what pleases us – whether it’s things or people. We can observe this in standing behaviour and sitting behaviour. If you’re standing and talking to someone it may begin with your feet not pointing towards the person – in other words, only from the hips up are you facing the person.

As the conversation progresses, you or the other person may gradually, without noticing, move the feet to face the other. It may happen quite naturally. If the feet stay pointed away (and towards the exit) then you don’t want to stay, or rapport hasn’t been established for whatever reason. Sometimes the feet may shift away during the interaction – it may be because a person has to go, or they are feeling discomfort and need to leave. You need to know why this has happened – a pressing engagement or disapproval?

During seating it’s often helpful – assuming that legs aren’t crossed – to note where the feet are pointing. If both feet are on the floor and one or both are not facing you, you haven’t quite attained that stage of interaction whereby everybody’s comfortable yet. Be aware of whether it’s due to seating position or a person’s state of mind.

You may equally have a situation where a person is sitting cross-legged in a chair with their feet facing away from you. Their crossed leg acts as a barrier against you. Again, check whether it’s due to their emotional state or the placing of furniture. Also:

- Was it a change of sitting posture?

- Was he previously facing you and has just now moved into a position away from you? (Was it something you said that didn’t go down well?)

At the next opportunity take a look at a group of people standing and talking. Do any of them have one foot pointing at a particular person – for example, a male with one foot pointing towards the female in the group, or vice versa. Watch for this on social occasions and at business ones too. It can reveal a lot (about you as well). We don’t usually know what our feet are doing.

Intention gestures

A common gesture that we all engage in is when we’re in a sitting position and we want to signal that we want to leave. Quite often it’s subconscious. We’ll adjust our feet to point to the exit. The hands would go on the armrests (or on the knees if there aren’t any) and we attempt to leave. If the person we’re with fails to pick up on the signal and carries on talking, we have to go through it again – and again. It can cause irritation if the signals are not picked up.

BODY WISE

Being the furthest point from the brain, we’re usually unaware of what our feet are doing and where they’re facing.

Apart from pointing in a certain direction, if we notice – either when standing or sitting – that a person’s feet are fidgeting, this displacement of energy tells us that the person can’t wait to get out of the situation. Similarly, tapping of the feet (as with fingers) denotes a person running out of patience.

Legs

Just as feet can provide a clue as to what our intentions are or where we’d really like to be, so the legs can reveal a lot, especially as part of a cluster. Leg crossing (which is usually right over left) often forms part of a cluster with the arms to reveal negative or defensive attitudes. Unlike crossed arms, we can’t take the leg-cross in isolation as an indicator of discomfort.

BODY WISE

Be careful in interpreting crossed-leg gestures with women because it may be for comfort reasons or because of clothing – as opposed to being attitudinal.

It is with the crossed-arms position then that the crossed legs reveal anything, because even with men it’s sometimes adopted out of habit or because of an uncomfortable chair. Generally, for both men and women, crossed arms and legs suggests trouble. As we noted earlier, something has to be done to ‘open them up’, and at the very least to find out what’s causing the negative attitude.

Sometimes it’s the ankles that are crossed rather than the legs. With a woman the knees tend to be held together – hands may rest on the lap. With a man the legs are usually spread out and the hands may rest on the sides of the chair. Again, as we’ve said before, it’s the impression that it relays to other people that’s important. If an ankle lock makes you look defensive – and therefore not ‘open’ – is that what you really want to convey?

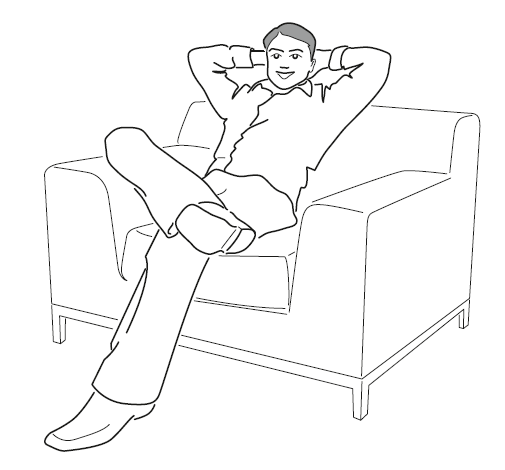

Just a word about an irritating ‘crossed’ position that is exhibited by men (often referred to as the ‘four-square’ position). You’ve seen it before and at times (just you males) you’ve been guilty of it. The ‘superior’ hands behind the head and one leg crossed over with its ankle supported by the knee of the other leg. The ‘one day you could be as wonderful as me’ pose. There are certain professional people who exhibit this with their subordinates. Women are particularly irritated if they’re in the same room and they see it, even if it’s not directed at them. It may be okay for a Hollywood film producer but away from the glitz it’s a turn-off.

BODY WISE

The feet and legs are the most ‘honest’ parts of the body.

Proxemics

The American anthropologist Edward Hall introduced us in the 1960s to the concept of ‘proxemics’, deriving from proximity – nearness in other words. He spoke of ‘personal space’ and how as territorial animals we impose an invisible ‘bubble’ around us for protection.

We do it at work by forming barriers in our offices, for example. The fashion for open-plan offices leads to staff using things like framed photographs, oversized staplers and pot plants to erect barriers between them. If you travel on trains and the London Underground (that’s a double-whammy) you’re probably used to ‘space invaders’ while you’re standing gripping tightly onto your two inches of clear rail. Your normal ‘bubble’ has been pricked and the only way you can cope is by:

- no eye contact

- turning the head away

- closed body language (as you pull back) – and maybe a newspaper as a barrier.

Somehow, as psychologist Robert Sommer suggested, we’re able to cope with uncomfortable crowded situations and a violation of our personal space by tricking our minds into believing that the person is inanimate. As such, the normal conventions of social behaviour don’t apply – if they accidentally touch us we ignore it, we adopt a blank expression and we also avert our gaze. A similar level of behaviour pattern exists in lifts as they go up and down floors.

In normal everyday interactions, taking account of humans’ spatial needs, Hall suggested that there were invisible zones that were suitable for specific situations. Depending on the relationship you had with somebody, each zone represented how close you allowed that person to come near you. Mmm . . that’s interesting, isn’t it? How many times have you been turned off ladies (question specifically for females) by someone who comes just a little too close to you for comfort? In a ‘stranger’ situation, social situation, work situation or flirting situation – maybe all of these?

These are people who just don’t quite get it, do they? Either they’re taking liberties, or they plainly don’t know (never been taught) – or maybe they’re from a different culture. Whatever – it’s irritating, isn’t it? It’s not just confined to females of course. We all experience it, male and female alike.

How many times have you ‘rejected’ a person because their distance just didn’t feel quite right? Everything else was okay, but they didn’t respect your personal space ‘bubble’ – they didn’t know what the appropriate ‘zone’ was.

Appropriate zone data

- Close intimate: 0–6 inches. Reserved for very few – lovers or people (e.g. your children) who you don’t mind touching you (as such, the most intimate behaviours are permissible).

- Intimate: 6–18 inches. Only the most important people – lovers, close relatives, close friends – are permitted. If strangers or people you don’t know well, or don’t like, violate this space, you feel uncomfortable.

- Personal: 18 inches–4 feet. Arm’s length – you are able to shake hands in this zone. This is the ideal one in the western world for most personal interaction. You’ll notice this distance at social functions, maybe office functions and parties, or ‘networking’ events. (Sommer noted that if you stand outside this space, it can cause negative feelings in the other person.)

- Social: 4 feet–12 feet. People who are not familiar to us who we may have to interact with – for example, tradesmen or shop floor assistants in stores.

- Public: 12 feet and over. When addressing a group of people in a formal setting, this was considered to be an acceptable distance from the front row. Usually there’s no social interaction in this zone.

We can gauge, or more realistically guess, the extent of a ‘relationship’ between one person and another by the distance between them – and also, at times, how they feel about each other.

BODYtalk

Q Should we be striving for ‘open’ body language most of the time?

With your normal relationships, yes. If you came across a grizzly bear nobody would be surprised if your posture and limbs adopted a more closed position and formed some kind of barrier and adopted a position of defensiveness. So, generally in most of our interactions in life, we’ll assume that we’re looking for harmony and cooperation, and it’s open body language that is ideal for achieving this.

Q I’m worried about my arms now. I didn’t know that for years I’ve been crossing them in various ways. When I’m with friends, during meetings, at the theatre, standing in line at the bank – I suppose if I analyse it, in most of these situations I’m not feeling great. So according to what you told us earlier, I’m reflecting my feelings to the outside world. No harm done in most cases I suppose, but I guess my friends could be offended while they’re telling me that long-winded story; and also in meetings, I’m wondering what messages I must have been giving out.

You’re right. You may get absolution for some of these instances. But remember what we said – it’s what the other person perceives that’s important. What you need to be aware of from now and always is that the longer you stay in a particular cluster gesture – let’s say folded arms with folded legs – the longer you keep that feeling. So you get to the stage where first of all the mind controls the body. Then, when you’ve adopted a certain position, the body controls the mind. So effectively you’re stuck.

So the way to get out of this rut has to be, initially, through self-talk. Since your thoughts control your emotions, which then tell your limbs how to behave, it’s only your new thoughts that can get you to unlock. Unless you’re lucky enough, in this instance, that your girlfriend is in the theatre with you and hands you a bar of chocolate.

Q Can we talk about these displacement gestures? I now know that I’m at it all the time. I’d like to dazzle people with my knowledge the next time we’re having a drink. I missed the definition you gave earlier. Can you give me a one-liner?

Sure. It’s any gesture we make to displace nervous energy.

Q Can I twist your arm for a similar one-liner for self-comfort gestures?

Well – I’d rather you left my limbs out of it, but here goes. It’s a gesture directed towards your own body to comfort you. (Much of it goes back to childhood.)

Q I’d like to ask about these hand-to-face activities. So, if I see someone touching their nose when I ask them if there’s any problem with the roof – we’re going for a second viewing of a house in a week’s time – can I assume they’re lying?

No – ID 10T error. We’ll be discussing the nose touch in Lesson 5. They might have an itchy nose – just at the time you asked them that question. However, if you noticed a pattern in this activity every time you asked an awkward question, and also if there’s a cluster of other signals, you could be barking up the right tree.

Q I find myself gripping the arms of a chair and putting my feet under the chair when I’m with people. They’ll understand that it’s not a defensive or nervous gesture, won’t they?

No.

Q I find myself always gripping my hands with fingers together when I’m summoned to a meeting at work. Is my subconscious telling me something?

Yes – that you’re experiencing discomfort. And it’s telling the astute members of the audience too.

Coffee break ...

- Of all our body parts the hands are the most spontaneous.

- There are more nerve connections between the brain and hands than any other part of the body.

- An ‘open’ hand in conjunction with the palm up position is associated with honesty and trust.

- Things you do to help displace anxiety or nervous energy are known as displacement activities.

- Some displacement is externally directed, such as fiddling with keys or a pen.

- Self-comfort gestures are internally directed.

- With the hand clasp where there are usually two main positions, the higher the position, the more nervous tension exists.

- When the arm behind the back grips the wrist it usually signals annoyance or frustration.

- With hand-to-face or -head gestures we tend to touch areas that may have been used to comfort us as children.

- Never underestimate the power of touch because our skin has receptor cells that are very sensitive and responsive to the power of touch.

- The typical hand-to-face gesture for boredom (while seated) is with the hand supporting the entire jaw with elbows resting on the table.

- Always look for a cluster of gestures to support your assessment.

- To check for boredom signals you need to look at the eyes.

- When the listener engages in a mouth cover with the fingers covering the mouth, it usually indicates they disagree with something or that the person is not telling the truth.

- If a speaker performs a mouth cover directly after saying something, it usually indicates they are lying.

- If a person has their fingers in their mouth it usually signifies some form of deceit.

- When the thumb supports the chin with the index finger vertical it is not usually a positive sign.

- With the evaluation gesture it’s the position of the thumb that gives you the clue.

- In body language terms the folding of arms has the capacity to form a barrier.

- Studies confirm that people seeing crossed arms will nearly always interpret it as a defensive or negative gesture.

- To minimise the display of the crossed arms as a defensive gesture you’ll sometimes see the partial arm-cross (quite common with women). Also, especially popular with celebrities and people in the public eye is a variation of this, the disguised arm-cross.

- Unlike crossed arms, we can’t assume that crossed legs are a sign of defensiveness; we have to look for a cluster of behaviour.

- Feet provide a good clue to a person’s feelings and intentions – note whether they’re pointing towards or away from you.

- The study of personal space is known as proxemics – there are four identified zones.

- The ideal zone in the western world for most personal interaction is the ‘social’, which extends from about 18 inches to 4 feet.